Anti-Government Demonstrations and Separatism in Thailand:

Political Disorder Trends Ahead of the 2023 General Election

23 February 2023

Introduction

With the general election in Thailand anticipated in May 2023, tensions that have sparked unrest in the country in previous years remain unresolved, despite declines in particular types of political violence and demonstration events in the past year. Political disorder in Thailand ranges from violence involving separatists in the Deep South to demonstrations over the continued presence of the monarchy and the military in politics. Following an increase in 2021, political violence involving separatists in the Deep South had been on the wane in 2022 until attacks in August caused a significant spike. Meanwhile, amid ongoing judicial harassment under the lèse-majesté law that criminalizes criticizing the monarchy, anti-government demonstrations calling for an end to the monarchy and the military in politics declined in 2022 compared to the previous two years. Yet the tensions underlying the street protests – as evidenced by the uptick in demonstrations in November during the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation summit and the hunger strike initiated earlier this year by two activists charged under the lèse-majesté law – have not been put to rest. The stage is set for the possible reemergence of demonstrations and disorder in Thailand around the upcoming election this year. Drawing on new data,1ACLED has recently completed a supplemental coding project for Thailand, which has added over 1,300 new political disorder events to the dataset. The supplemental coding project covered the Thai language versions of 11 sources which had previously been sourced in English; the real-time data released each week cover Thai and English language sources. The supplemental project also includes corrections to previously coded events. ACLED also continues to integrate data from our local partner, Deep South Watch. This ongoing data-sharing partnership continues to strengthen ACLED’s data on the conflict in the Deep South. Data from Deep South Watch are added to the ACLED dataset approximately every six months. Data for the second half of 2022 will be added in the coming months. Differences in event counts between Deep South Watch and ACLED are attributable to differences in sourcing and coding methodologies. ACLED maintains a ‘living dataset,’ with data revised as more information becomes available about events. For more on what users should keep in mind when using ACLED’s historical data (events coded prior to 2018), see Adding New Sources to ACLED Coverage. this report examines political violence and demonstration trends under the administration of Prime Minister Prayut Chan-o-cha, the leader of the 2014 military coup, from the previous general election in March 2019 to the end of 2022.

Declining Anti-Government Demonstrations Amid Judicial Harassment

The current youth-led anti-government movement in Thailand emerged following the 2014 military coup led by Prayut Chan-o-cha, with demonstrations calling for an end to the military’s role in politics escalating in 2020. Demonstrations initially increased in response to the constitutional court’s dissolution in early 2020 of the Future Forward Party (FFP), a popular progressive, anti-junta party that won a number of parliamentary seats in the 2019 election.2Bangkok Post, ‘FFP dissolved, executives banned for 10 years,’ 21 February 2020 The election ultimately resulted in Prayut’s military-backed Palang Pracharath Party coming to power, with Prayut remaining as prime minister.

Anti-government demonstrations have not only challenged the military, but also evolved into a challenge to the monarchy. For centuries, the monarchy has been promoted as the spiritual pillar and unifying force of the nation. Criticizing the monarchy is widely frowned upon and legally prohibited.3Christian Kurzydlowski, ‘Thailand’s Protesters Are Battling to Redefine National Identity,’ The Diplomat, 2 November 2021 The lèse-majesté law, Article 112 of Thailand’s Criminal Code, stipulates that defaming or insulting members of the royal family is unlawful and can result in up to 15 years of imprisonment for each conviction. Human rights groups have condemned its use as a political tool and a means to restrict freedom, as anyone can file the charge, and trials are usually closed to the public.4BBC, ‘Lese-majeste explained: How Thailand forbids insult of its royalty,’ 6 October 2017

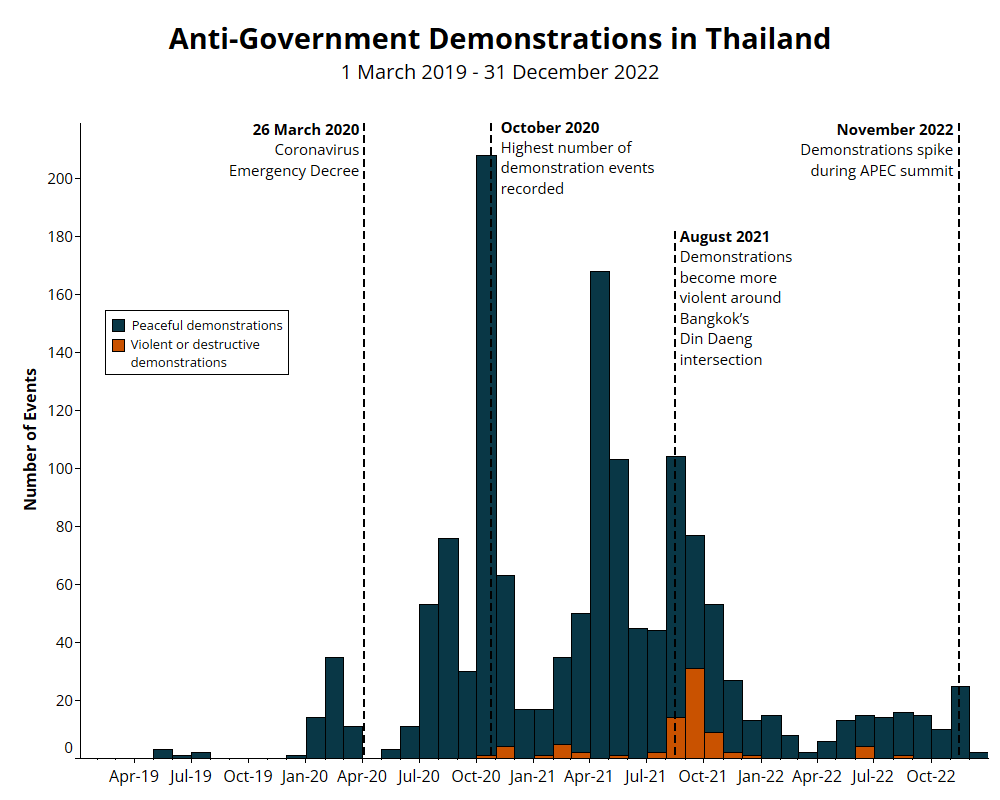

Following heightened levels in 2020 and 2021, anti-government demonstrations decreased in 2022 (see figure below) amid the ongoing prosecution of activists under the lèse-majesté law. Some protesters who joined the demonstrations over the last three years remain in jail. Anti-junta activist groups, such as Resistant Citizen, have been calling for the release on bail of the arrested protesters and an end to the lèse-majesté law. Utilizing creative protest tactics, they have staged ‘stand-still’ protests, standing for one hour and 12 minutes to symbolize Article 112 of the Thai Criminal Code, the lèse-majesté law.5Anusorn Unno, ‘‘Stand, Stop, Imprison’: People’s Defiance against the Thai Establishment,’ Fulcrum and ISEAS Yusof Ishak Institute, 3 March 2022

Following the 2021 constitutional court ruling that held that reform calls by protest leaders were intentionally trying to overthrow the monarchy, the anti-government movement has turned towards pursuing monarchy reform through parliamentary processes rather than solely through street protests.6Reuters, ‘Thai court rules students’ royal reform call sought to overthrow monarchy,’ 10 November 2021 For example, one protest leader joined the Move Forward Party, a reconstitution of the anti-junta FFP, to run for parliament on the platform of monarchy reform and amendment of the lèse-majesté law.7BBC Thai, ‘Move Forward Party: Lookkate-Chonticha, a negotiator of “the People” joining Move Forward to run for MP, has promised to put forward monarchy reform through the Parliamentary process,’ 12 February 2022 There will likely be further attempts to reform the system through parliamentary means rather than demonstrations.

Demonstrators who do take to the streets have previously faced a heavy-handed government response. In 2021, violent demonstrations increased in August and September as demonstrators clashed with police in August at the Din Daeng intersection in Bangkok. Three demonstrators were shot by police, with one later dying from his wounds.8Thanarat Khiaolailoet, ‘Din Daeng Intersection: a battlefield where people willing to take on the state,’ Prachatai English, 21 September 2021 Additionally, counter-demonstrations by royalists have also been reported – notably in 2020 as anti-government demonstrations evolved into calls for monarchy reform – though they did not rise to the ‘yellow-shirt’ (royalists) versus ‘red-shirt’ (opposition) levels of contention of the 2006–14 period.

Enduring Separatist Violence in Thailand’s Deep South

The 2023 general election is also likely to influence the direction of the government’s policies toward the separatist conflict in the Deep South. Opposition political parties supported by anti-junta groups are seen as having a more liberal approach to the separatist conflict, meaning a greater openness to discussions of separatist political demands.9Rungrawee Chalermsripinyorat, ‘Thailand’s deep south conflict is approaching a critical point,’ Nikkei Asia, 13 September 2022 By contrast, the military has traditionally been resistant to recognize Malay concerns despite engaging in peace talks.10Don Pathan, ‘Thai Authorities Struggle to Understand a Conflict They Have Been Fighting for Decades,’ United States Institute of Peace, 13 September 2021

Bordering Malaysia, Thailand’s Malay Muslim-majority Deep South has been experiencing an ongoing separatist insurgency with roots reaching back to the 1786 subjugation of the Patani Sultanate to the Kingdom of Siam and the 1909 Anglo-Siamese treaty that established the current borders between Thailand and Malaysia.11Srisompob Jitpiromsri, Napisa Waitoolkiat, and Paul Chambers, ‘Special Issue: Quagmire of Violence in Thailand’s Southern Borderlands Chapter 1: Introduction,’ Asian Affairs: An American Review, 2018 Separatists in the Deep South contest control of the historical area of Patani,12Separatists use the spelling Patani with one ‘t’ to represent the historical Sultanate. Pattani province, in its current administrative form, is spelled with two ‘t’s. which covers the modern-day provinces of Pattani, Narathiwat, Yala, and four districts in neighboring Songkhla. They have traditionally largely put forth an ideology centered around Patani ethnic nationalism.13International Crisis Group, ‘Jihadism in Southern Thailand: A Phantom Menace,’ 8 November 2017

Armed separatist group activity has often ebbed and flowed in response to the state’s attempts to exert control over the region.14Pavin Chachavalpongpun (ed.), ‘Routledge Handbook of Contemporary Thailand,’ Routledge, 2020 Separatists target the military and police, as well as individuals seen as representing the Thai state, including local government officials, teachers, and Buddhist monasteries. Beginning in 2001 and accelerating in 2004, the intensity of violence in the region increased significantly, with the conflict leading to thousands of deaths, though the past decade has seen a gradual decline (see the Deep South Watch dashboard). Since July 2005, an emergency decree has been in effect in Pattani, Yala, and Narathiwat provinces. The decree has been criticized for exacerbating mistrust of the military and police in the region15International Crisis Group, ‘Thailand’s Emergency Decree: No Solution,’ 18 November 2005 and providing cover for abuses by state forces.16Bangkok Post, ‘Far South emergency ‘must end’,’ 20 July 2021

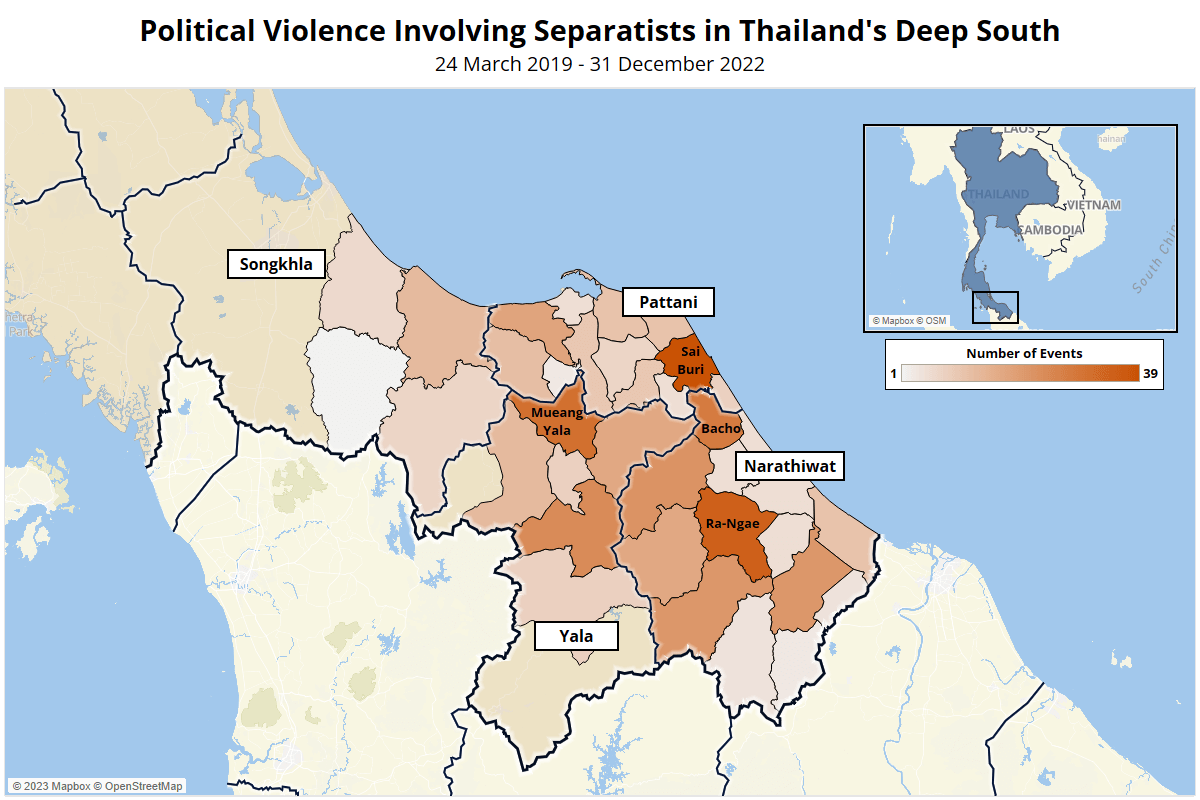

Political violence involving separatists is largely confined to the Deep South, though a few notable events have been recorded outside the region. Within the Deep South, separatist violence has clustered in Sai Buri, Ra-Ngae, Mueang Yala, and Bacho districts, which have recorded the highest number of events per district from 24 March 2019 to 31 December 2022 (see map below).

Various armed separatist groups have formed over the years. Currently, the largest separatist group is the Barisan Revolusi Nasional Melayu Patani (BRN). Other groups include the Patani United Liberation Organization (PULO), which until early 2022 had been largely dormant. Identifying armed separatists has proved to be a challenge, as many blend into society to the extent that addressing the insurgency has been described as “confronting ghosts.”17Joseph Chinyong Liow and Don Pathan, ‘Confronting ghosts: Thailand’s shapeless southern insurgency,’ Lowy Institute for International Policy, 2010 Many attacks are reported in the press as suspected to have been carried out by separatists without a particular group laying claim to the attack.18ACLED codes such cases using the actor “Malay Muslim Separatists (Thailand).” When a group, such as the BRN, claims an attack, it is usually meant to convey a message to the state during peace talks about the control it exerts over separatists.19Rungrawee Chalermsripinyorat, ‘Thailand’s deep south conflict is approaching a critical point,’ Nikkei Asia, 13 September 2022

Bangkok has traditionally refused to allow international involvement in mediation efforts in the conflict, reportedly concerned that such external involvement could strengthen the perceived legitimacy of the separatists.20International Crisis Group, ‘Sustaining the Momentum in Southern Thailand’s Peace Dialogue,’ 19 April 2022 Beginning in 2013, though, with Malaysia’s support, the Thai government under the Pheu Thai Party initiated talks with separatists. After the 2014 military coup which overthrew the Pheu Thai Party government, the military decided on a strategy of talking with all separatist groups in a bid to cause friction among different factions.21Zachary Abuza, ‘In 2023, expect more violence in Thailand’s insurgency-hit Deep South,’ BenarNews, 6 January 2023 This resulted in negotiations with Majlis Amanah Rakyat Patani (MARA Patani), a collection of separatist actors whose legitimacy was undermined as the group was not fully backed by the BRN.22Don Pathan, ‘A new round of negotiations in Thailand’s far South,’ Kyoto Review of Southeast Asia, September 2020

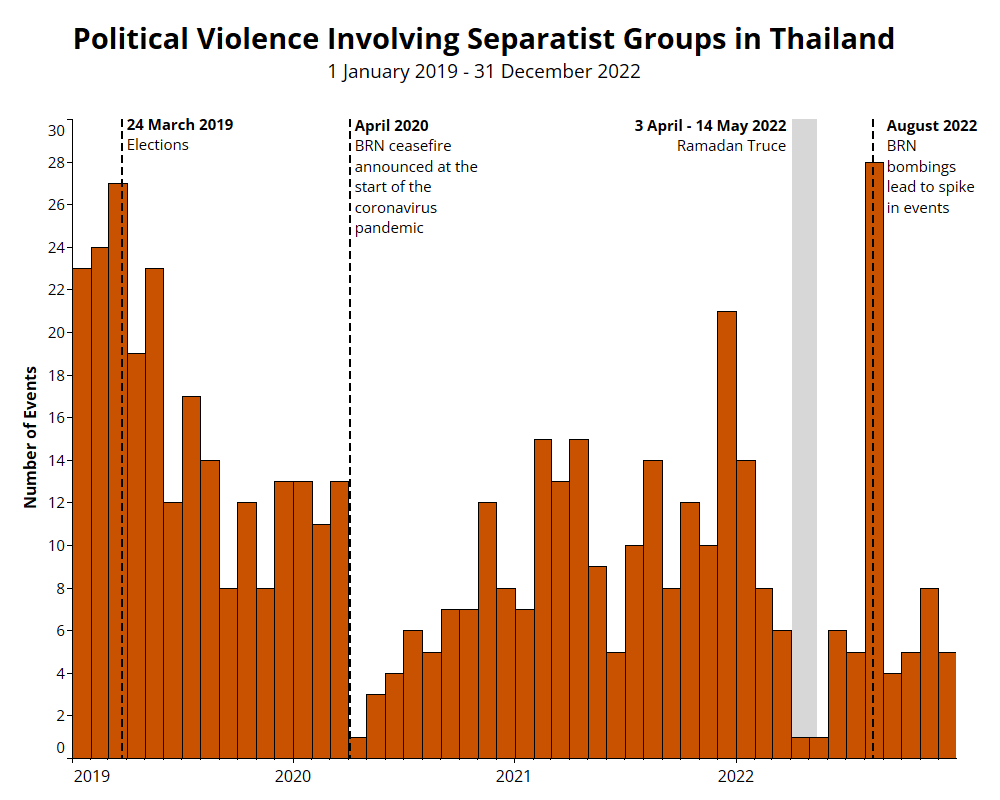

More recently, beginning in 2020, peace talks have been held directly between the state and the BRN. In-person meetings were halted by the coronavirus pandemic, though contact between the government and BRN was maintained.23International Crisis Group, ‘Sustaining the Momentum in Southern Thailand’s Peace Dialogue,’ 19 April 2022 In April 2020, the BRN announced a de facto ceasefire due to the spread of the coronavirus,24Jason Johnson, ‘What to Make of South Thailand’s COVID Quasi-Ceasefire,’ The Diplomat, 3 June 2020 though it was short-lived, with political violence trending upwards in the months following the announcement (see figure below). This growth in political violence continued into 2021, with violence involving separatists remaining persistent and at higher levels in 2021 compared to 2020.

Peace talks between the two parties nonetheless resumed in 2022. A truce during the Muslim holy month of Ramadan between 3 April and 14 May 2022 led to a drop in violence.25BBC Thai, ‘Ramadan: BRN-Thai Government agree to ceasefire on the southern border during fasting,’ 2 April 2022 However, while the BRN limited its activity during this period, PULO carried out bombings in April. PULO expressed dissatisfaction with being excluded from the recent peace talks.26Isranews, ‘Pulo on the move! Leaving flyers and hanging banners, presumably hoping to join the negotiation table,’ 11 May 2022 After the attack, the BRN expressed a willingness for PULO to be included in peace talks with the state, to which the state appeared agreeable.27Mariyam Ahmad, Muzliza Mustafa, and Nisha David, ‘In Thai Deep South, another rebel group wants role in peace talks,’ BenarNews, 24 June 2022

The government later proposed a truce during talks in July for the Buddhist lent, a three-month period of reflection and meditation. The truce was marred by a series of explosions in August across Pattani, Yala, and Narathiwat provinces, which reportedly killed a civilian. The bombings, claimed by the BRN, drove a spike in conflict activity involving separatists in August when the number of events involving armed separatist groups was the highest in over two years. The BRN stated that the attacks, targeting convenience stores, were meant as a rebuke of the “power of capitalism,” which it views as supported by the government and military.28Bangkok Post, ‘BRN reveals motive for recent blasts,’ 19 August 2022 Despite the bombings, the government maintained that peace talks would not be derailed as a result.29Zsombor Peter, ‘Thailand Says Peace Talks with Muslim Insurgents Still on Track After Major Rebel Assault,’ Voice of America, 18 August 2022

Recently, the abduction and death of a BRN separatist in October has caused concern after the BRN insinuated that state forces were behind the killing, which the government denied.30Muzliza Mustafa et al., ‘Deep South rebel abducted, tortured, and killed, BRN says,’ BenarNews, 19 October 2022 Meanwhile, in November, separatists bombed police housing in Narathiwat province, killing a police officer and injuring many family members. The targeting of an area clearly inhabited by civilians led many human rights groups to call for an investigation.31Mariyam Ahmad and Matahari Ismail, ‘Rights group: Investigate Deep South bombing as ‘war crime’,’ BenarNews, 23 November 2022

While separatist groups have yet to make a statement regarding the upcoming election, MARA Patani suspended talks with the government a month before the 2019 general election.32Panu Wongcha-um, ‘In Thailand’s restive deep south, election stirs rare enthusiasm,’ Reuters, 22 March 2019 It remains to be seen if the BRN would take a similar approach. With the recent change in the Malaysian government, a new Malaysian facilitator for the talks has been appointed.33Francesca Regalado, ‘Malaysia PM Anwar enters Thai peace talks with separatist rebels,’ Nikkei Asia, 5 February 2023 The conflict was a key topic of discussion when Malaysian Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim visited Thailand on 9 February. Anwar noted that peace was “of paramount consideration” and that Malaysia was committed to continuing to facilitate peace talks.34Sebastian Strangio, ‘Malaysian PM Anwar Calls for Progress on Southern Thailand, Myanmar Conflicts,’ The Diplomat, 10 February 2023 The latest talks between the BRN and the government were held on 21-22 February in Kuala Lumpur.35Thai PBS World, ‘Southern peace dialogue offers “a light at the end of the tunnel”,’ 22 February 2023

While there may be a flurry of activity concerning the Deep South in the run-up to the election, the peace talks under the Prayut administration have thus far failed to move beyond temporary ceasefires to address deeper Malay concerns. This has meant that downturns in violence have frequently failed to transfer into more expansive improvements in the state of the conflict.

Looking Forward

In the run-up to this year’s general election, anti-government demonstrations may increase over the continued roles of the monarchy and the military in governing Thailand. With the constitutional court allowing Prayut to serve out the remainder of his term as prime minister and be eligible for two additional years after the election, the possibility of anti-government demonstrations reviving remains.36Enno Hinz, ‘Thailand: Will Prayuth ruling spark a new political crisis?,’ Deutsche Welle, 2 October 2022 Prayut recently joined a new political party amid reported rivalry between him and Deputy Prime Minister Prawit Wongsuwon, who remains the leader of the ruling Palang Pracharath Party.37Mongkol Bangprapa, ‘Parties urged to shun populism,’ Bangkok Post, 8 February 2023 Demonstrations are likely to increase if those associated with the 2014 military coup retain power, particularly if the election is not seen as free and fair.38Joshua Kurlantzick, ‘Prayuth’s Misrule Is Turning Thailand Into a Powder Keg,’ Council on Foreign Relations, 23 September 2022 Given the turn toward violence that such demonstrations took towards the end of 2021, the possibility of renewed demonstrations becoming violent exists, making the continued rule of the country by the network39Duncan McCargo, ‘Network monarchy and legitimacy crises in Thailand,’ The Pacific Review, 20 August 2006 of monarchy and military-backed actors fraught with the potential for disorder.

If monarchy- and military-backed politicians do not win, and an opposition party does come to power, there could be an uptick in demonstrations by royalists, depending on the policies enacted by the opposition. In addition, given the frequency of coups in Thailand, the question arises of a possible military coup in reaction to such a potential transfer of power, though the military has promised that there would be no coup after the election.40Sebastian Strangio, ‘No Post-Election Coup, Promises Thai Commander-in-Chief,’ The Diplomat, 14 October 2022

Trends in separatist activity will likely be connected with progress in the ongoing peace talks, as well as separatist perceptions of the utility of violence in the run-up to the election. The government’s policies and engagement with separatists in the Deep South will be shaped by the results of the upcoming election, given the noted differences between military and opposition approaches to the conflict. Opposition parties are more likely to engage with Malay political demands, though they will remain constrained by the military’s role in the process.41Zachary Abuza, ‘In 2023, expect more violence in Thailand’s insurgency-hit Deep South,’ Benar News, 6 January 2023 In all, existing tensions underlying long-standing patterns of disorder in Thailand are likely to persist as the election approaches.

Visuals in this report were produced by Ana Marco.