Context Assessment

Increasing Security Challenges in Kenya

2 March 2023

Introduction

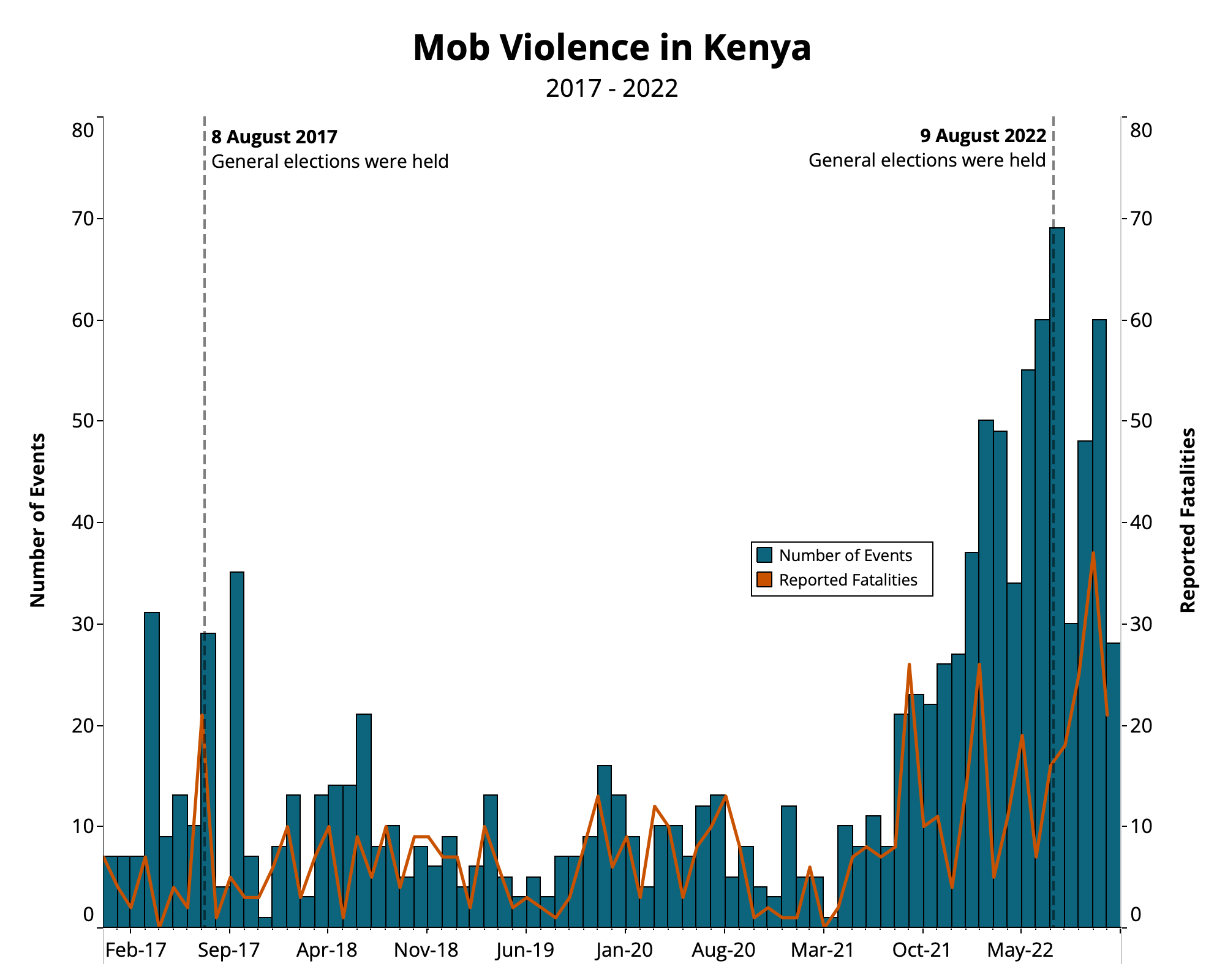

The 2022 Kenyan general election was characterized by highly contested party nominations and a violent campaign period. ACLED records peaks in political violence events in the lead-up to and on election day on 9 August 2022. William Ruto’s United Democratic Alliance (UDA) party under the Kenya Kwanza (Kenya First) Alliance garnered a razor-thin victory against veteran opposition leader Raila Odinga of Azimio La Umoja (Resolution for Unity) One Kenya Coalition Party. Ruto secured just over 50% of the votes, thus avoiding a run-off.1The East African, ‘How Ruto won State House race,’ 16 August 2022 The results were later unanimously affirmed by the Supreme Court, paving the way for a smooth transition of power from incumbent President Uhuru Kenyatta to his then-deputy Ruto.

Ruto’s election victory came while Kenya was experiencing increasing levels of low-intensity violence across the territory. ACLED data demonstrate a significant increase in the number of political violence events in 2022 compared with the previous five years. In 2022, ACLED records more than 990 political violence events, resulting in almost 700 reported fatalities. Three main factors contributed to the increase in political violence in Kenya last year: heightened al-Shabaab activity in coastal and northern Kenya; increasing activity by pastoralist militias, especially in northern Kenya; and highly contested party nominations and a violent campaign period, leading to a rise in the number of mob violence events. Nairobi, Turkana, Mandera, Baringo, and Kakamega counties had the highest number of political violence events in 2022. Reported fatalities were highest in Turkana, with almost 70 reported fatalities, where Pokot militias attacked civilians and clashed with state forces. Lamu followed with 68 reported fatalities, mostly due to clashes between al-Shabaab militants, and police and military forces.

Patterns of Political Violence in 2022

Heightened al-Shabaab Activity

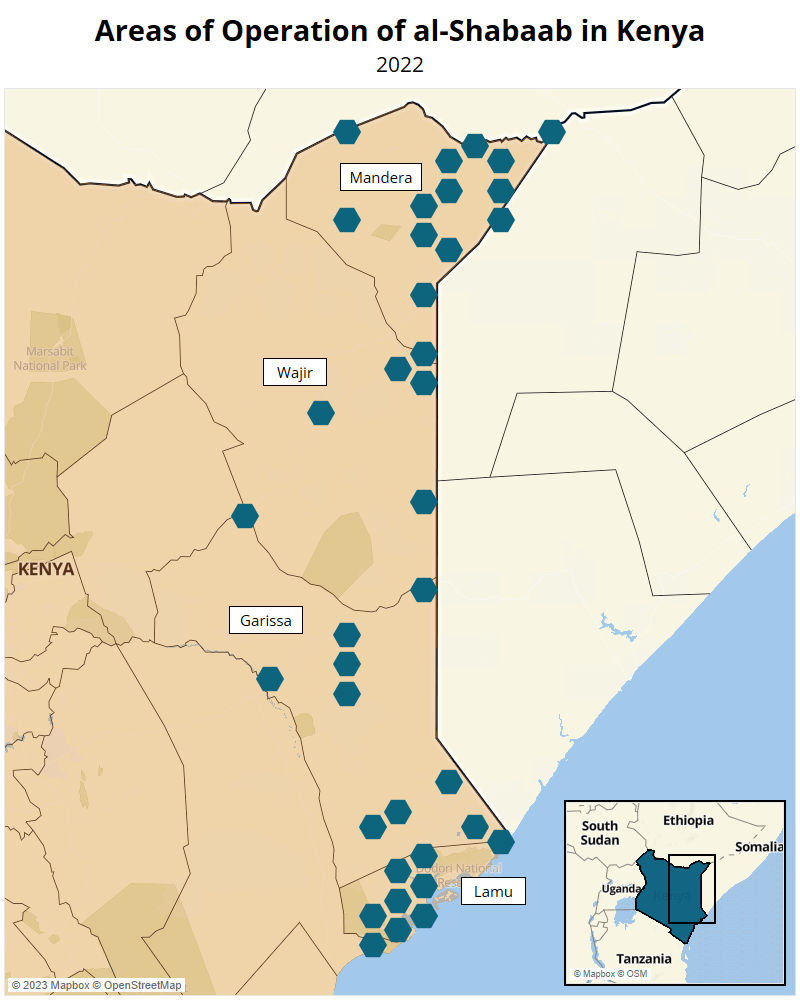

Al-Shabaab’s activity intensified last year. ACLED records a 66% increase in the number of political violence events involving the group compared to 2021. Al-Shabaab was largely operative in the counties bordering Somalia, including Mandera, Lamu, Garissa, and Wajir (see map below). Mandera county had the highest number of political violence events resulting from al-Shabaab activity, both in 2021 and 2022.

Mandera and the rest of the northern counties have grappled with repeated attacks by al-Shabaab militants, mainly due to proximity and large porous border with Somalia; this makes it easy not only for the militants themselves, but also their weapons to gain entry into Kenya.2The East African, ‘How Ruto won State House race,’ 16 August 2022 In Lamu and Garissa counties, militants have used the dense Boni forest as a hideout. Moreover, Kenyan authorities also claim that militants are funded by profits made from illegal logging and charcoal-burning activity inside the forest.3Xinhua, ‘Kenyan security forces kill 15 al-Shabab militants in coastal region,’ 19 January 2022; Shabelle Media Network, ‘Somalia: Charcoal, Illegal Logging Fund Al-Shabaab Militants Hiding in Boni Forest,’ 28 March 2018

The bulk of al-Shabaab activity in Kenya consists of armed clashes with Kenyan security forces, which recorded a 75% increase last year compared with the previous year. In a notable development, al-Shabaab militants fired several mortar shells toward a Kenyan military base in Lafey sub-county, Mandera county, overnight on 19 August.4Wararka Gudaha, ‘Ciidamada Kenya oo lagu weeraray NFD iyo Jubbada Hoose,’ SomaliMemo, 19 August 2022 In August, al-Shabaab deployed shelling in Kenya for the first time since 2018, an indication that its attacks have likely increased in sophistication.

Yet, the group has also engaged in direct attacks against civilians, resulting in approximately 40 reported civilian fatalities in 2022, more than double the number recorded in 2021. This includes the use of remote violence, which saw an almost three-fold increase last year relative to 2021. The majority of the victims were workers, including foreign nationals working on the Lamu Port South Sudan-Ethiopia Transport (LAPSSET) Corridor project. Private and public vehicles were also targeted by remote violence. Closely related is al-Shabaab’s destruction of security installations, such as telecom masts, to disable communication and coordination by security officers before engaging in attacks in areas such as Rhamu in Mandera county.5Cyrus Ombati, ‘Al-Shabaab terrorists destroy communication mast in Mandera,’ The Star Kenya, 21 June 2022

The new administration is set to continue its counter-terrorism efforts against al-Shabaab. The Kenyan military is not only engaged against al-Shabaab domestically, but has also contributed troops to the African Union Transition Mission in Somalia (ATMIS). Kenyan troops are present in regions in southern Somalia adjacent to the Kenya border. ATMIS’s term will expire in 2024 when its responsibilities are handed over to Somali security forces.6Martine Zeuthen, ‘A New Phase in the Fight against al-Shabaab in the Horn of Africa,’ International Centre for Counter-Terrorism, 21 September 2022; Daily Nation, ‘UN Security Council approves African Union Transition Mission in Somalia,’ 1 April 2022

Intensified Violence Involving Pastoralist Militias

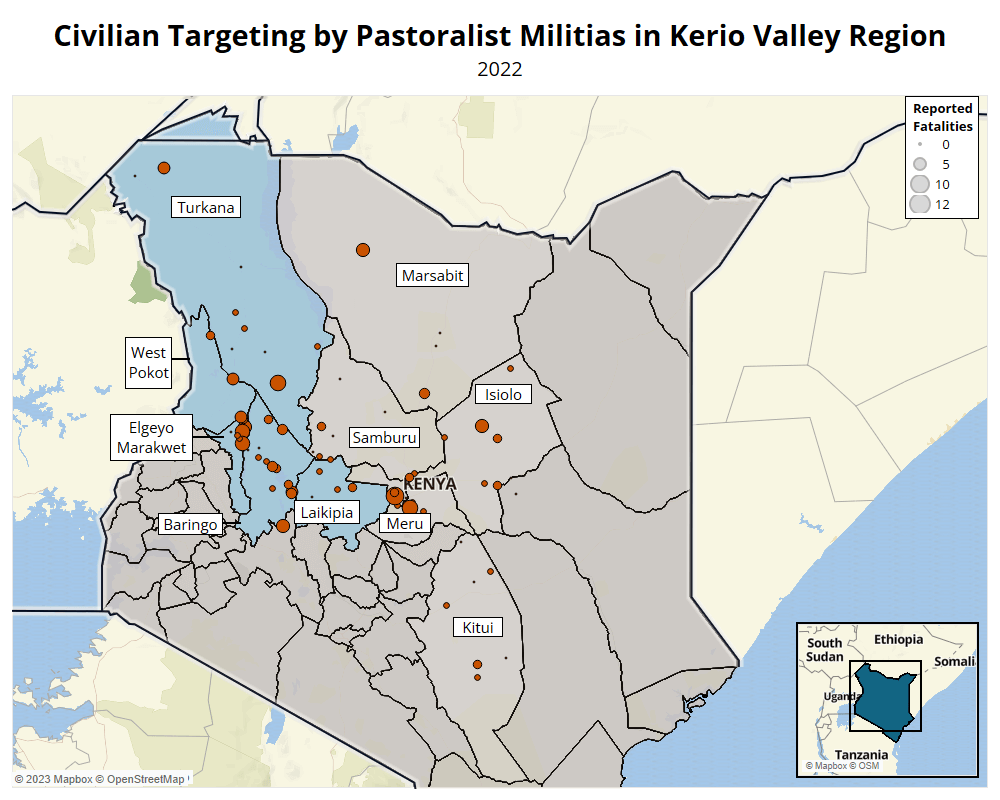

Kenya also faces a rising security threat as a result of pastoralist militia activity. The Kerio Valley region – which includes West Pokot, Baringo, and Elgeyo Marakwet counties, plus neighboring Turkana and Laikipia counties – and the northeastern counties of Isiolo, Samburu, and Marsabit, among other arid and semi-arid lands, are the areas most affected. The region has suffered from increasing inter-communal violence involving pastoralist militias in the past year and continues to experience sustained tensions. Competition over access to limited pasture and water resources as a result of prolonged drought,7Sammy Lutta, ‘10,000 on brink of starvation as dought, banditry take toll,’ Daily Nation, 23 January 2023 in addition to the proliferation of small arms smuggled from neighboring countries such as Ethiopia, South Sudan, and Somalia, are cited as some of the drivers of violence.8Bruhan Makong, ‘East Africa: Ruto Says Conflicts in the Horn Fueling Banditry, Vows Efforts to Tame Proliferation of Arms,’ Capital FM, 11 January 2023

ACLED records 170 political violence events involving pastoralist militias in 2022, representing a 139% increase compared with the previous year. At least 193 reported fatalities were recorded, with civilian fatalities constituting the majority of overall reported fatalities driven by pastoralist militia activity. Across the 47 counties of Kenya, Baringo had the highest number of civilian fatalities in 2022 with 27 reported fatalities, followed by Elgeyo Marakwet and Isiolo, each with 23 reported civilian fatalities as a result of attacks reportedly staged by pastoralist militias (see map below).

The violence has also involved retaliatory attacks on women and children – including students, leading authorities to decree school closures. Among these events was the deadly shooting of a family of five in a suspected retaliatory attack at Ngarendare in Oldonyiro, Isiolo county.9Waweru Wairimu, ‘Two children shot dead, 3 others injured in Isiolo bandit attack,’ Daily Nation, 17 December 2022

Pokot ethnic militias alone were involved in almost 60% of the total political violence events by pastoralist militias in 2022. Largely inhabiting West Pokot and parts of Baringo counties, Pokot militias are allegedly linked to the wider network of so-called “cattle warlords,” often spanning communal and international borders.10Ronald Musoke, ‘ANALYSIS: East Africa’s cattle warlords,’ The Independent (Uganda), 11 March 2020 The cattle warlords reportedly provide ammunition to Pokot militias to facilitate their cattle-stealing activity.11Florah Koech, ‘Mystery of ‘white helicopter’ in Baringo banditry attacks,’ Daily Nation, 11 March 2022; Shiko Ngure, ‘Let’s explore possible ways to end cattle rustling, banditry,’ Daily Nation, 11 January 2023 Moreover, 70% of the events involving Pokot ethnic militias are violence against civilian events, while the remaining events primarily consist of clashes with Kenyan security forces. In fact, activity by the group significantly increased in 2022, almost tripling compared to the previous year.

The Kenyan government has prioritized the recruitment and deployment of National Police Reserve (NPR) personnel to work alongside police in addressing the conflict challenges in the areas prone to pastoralist militia attacks. Given that NPR members come from the community, they are presumed to be more effective in addressing insecurity as they understand the terrain and even the hideouts of the militias.12Fred Kibor and Onyango K’Onyango,’Police reservists reinstated in troubled Kerio Valley after President Ruto’s order,’ Daily Nation, 9 November 2022 Under Kenyatta’s presidency, the government decreed several 30-day dusk-to-dawn curfews in selected counties affected by pastoralist militias, followed by security operations to enforce the curfews.13Julius Chepkwony, ‘Dusk to dawn curfew imposed in North Rift regions affected by insecurity,’ The Standard, 7 June 2022

Increased Mob Violence During the Election Year

Mob violence peaked in 2022, with Kenya registering almost 550 mob violence events – the highest number of such events in any country on the African continent. Most of this violence was concentrated in Nairobi county, where 101 mob violence events and 46 reported fatalities were recorded, followed by 35 mob violence events in Kakamega county with a dozen reported fatalities. The months of June to August, in particular, saw an increase in mob violence events (see graph below), mostly due to the highly contested party nominations and a violent campaign period in support bases of both Kenya Kwanza Alliance and Azimio La Umoja One Kenya Coalition Party. In fact, reported rioting in the lead-up to the 2022 elections far exceeded the level of activity reported ahead of any previous election (for more, see Kenya’s Political Violence Landscape in the Lead-Up to the 2022 Elections).

ACLED records several reported fatalities resulting from mob violence during the election period. For instance, on 14 July 2022, people armed with crude weapons, presumed to be supporters of an independent gubernatorial candidate, beat to death a supporter of the Orange Democratic Movement party member of the Azimio coalition in Kotora area of Rangwe sub-county in Homa Bay county.14Purity Wangui, ‘Stop acts of violence in Homa Bay, Gladys Wanga tells rivals,’ The Star Kenya, 15 July 2022 In another instance, on the morning of election day, UDA and Democratic Action Party supporters, allied to rival parliamentary candidates, clashed with each other at Kibachenje area of Bumula sub-county, Bungoma county. Four people sustained gunshot wounds, and four vehicles were destroyed during the incident.15Tony Wafula, ‘Four injured as Bumula constituency candidates clash,’ The Star Kenya, 9 August 2022 More recently, in December, a by-election for the member of the county assembly in Siaya turned chaotic after rival groups clashed with each other, resulting in 15 people injured and three vehicles damaged at Kambare primary school.16Citizen TV Kenya, ‘15 people injured in south gem ward by-election violence,’ 8 December 2022

Looking Forward

ACLED will closely monitor the multifaceted threats to Kenya’s security and publish regular reports exploring and analyzing how key trends evolve in the country, including but not limited to:

- Al-Shabaab activity, with special attention to emerging trends, locations, the use of remote violence, and effects on development infrastructure – including the LAPSSET Corridor project;

- Security threats posed by pastoralist militias’ activities, their locations, specific actors and accompanying actor profiles, and their interactions with Kenyan security forces and other militia groups;

- The government’s strategic response to security challenges, including the deployment of NPR forces by arming civilians, and parliamentary legislations around managing pastoralist militias – for example, the planned move to classify cattle rustling and banditry as acts of “terrorism;”17Fred Kibor, ‘Rift Valley leaders want banditry classified as terrorism,’ Daily Nation, 5 January 2023 and

- Demonstration activity by the opposition against the Ruto administration. The opposition has lined up a number of rallies to protest against the government, while demanding the removal of punitive taxes.18Naomi Njoroge, ‘Raila announces series of rallies to protest against Ruto’s administration,’ People Daily, 29 January 2023