The Resurgence and Alliances of the March 23 Movement (M23)

23 March 2023

Introduction

The March 23 Movement (M23) — Mouvement du 23 Mars in French — is an armed group operating in Nord Kivu province of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), with alleged backing from the Rwandan government. The roots of the M23 go back to the disrupted integration process of Rwandophone militants following the Congo Wars, splitting those willing to return to Rwanda and others desiring to stay in DRC.1Maria Eriksson Baaz and Judith Verweijen, ‘The Volatility Of A Half-Cooked Bouillabaisse: Rebel-Military Integration And Conflict Dynamics In The Eastern DRC,’ African Affairs, October 2013 Many fighters remained in Nord Kivu province to form the National Congress for the Defence of the People (CNDP) under the leadership of a former Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) militant, Laurent Nkunda. A precursor to the M23, the CNDP claimed to protect Congolese Tutsi and received Rwandan support.2Jason Stearns, ‘From CNDP to M23: The Evolution of an Armed Movement in Eastern Congo,’ Rift Valley Institute, 2012 The M23’s name comes from the failed negotiation process between the CNDP and the Congolese government on 23 March 2009.3Furaha Umutoni Alida, ‘“Do They Fight for Us?” Mixed Discourses of Conflict and the M23 Rebellion Among Congolese Rwandophone Refugees in Rwanda,’ African Security, 28 May 2014

The historical linkages between the M23 and the CNDP underscore the importance of the failed integration of CNDP fighters into the Congolese military forces (FARDC), and ongoing violence against Congolese Tutsi and other Kinyarwanda speakers as grievances held by the M23.4Jason Stearns, ‘From CNDP to M23: The Evolution of an Armed Movement in Eastern Congo,’ Rift Valley Institute, 2012 Congolese Tutsi and many Hutu are often considered ‘outsiders’ from Rwanda despite their longstanding residence in DRC.5Catherine Boone, ‘Property and Political Order in Africa: Land Rights and the Structure of Politics,’ Cambridge University Press, 2014, p. 157 – 176, 284 – 295 The migration of many Rwandophones took place in numerous waves over several hundred years, many arriving more recently after the 1994 genocide in Rwanda.6Gillian Mathys, ‘Bringing History Back In: Past, Present, And Conflict In Rwanda And The Eastern Democratic Republic Of Congo,’ Cambridge University Press, October 2017 Although occupying positions of power in government and business, Rwandophones have experienced prejudice and discrimination in DRC, especially concerning citizenship and land rights.7Jason Stearns, ‘From CNDP to M23: The Evolution of an Armed Movement in Eastern Congo,’ Rift Valley Institute, 2012

The integration process between the FARDC and former CNDP militants broke down in 2012, leading defecting fighters to establish the M23.8Jason Stearns, ‘From CNDP to M23: The Evolution of an Armed Movement in Eastern Congo,’ Rift Valley Institute, 2012 The M23 quickly took over territory in Nord Kivu province, including the provincial capital city of Goma that borders Rwanda. The militants held Goma briefly in late 2012, with political violence spiking in November before the M23 withdrew in December; this followed agreements between the Congolese government and M23 brokered by President Yoweri Museveni of Uganda, President Joyce Banda of Malawi, and UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon.9Jeffrey Gettleman, ‘Rebels Pull Out of Strategic City in Congo,’ New York Times, 1 December 2012; International Conference of the Great Lakes Region, ‘Joint ICGLR-SADC Final Communiqué on the Kampala Dialogue’, 12 December 2013 M23 violence continued around Goma in the following months, especially in Rutshuru and Nyiragongo territories. Between 2012 and 2013, the M23 engaged in over 20% of all political violence events in DRC recorded by ACLED, becoming the most active non-state armed group in the country during this time. Eventually, a strong offensive by the FARDC and United Nations peacekeepers in November 2013 inflicted heavy losses among the M23 ranks, alongside a reduction in Rwandan military support.10Ben Shepherd, ‘Elite Bargains and Political Deals Project: Democratic Republic of Congo (M23) Case Study,’ United Kingdom Stabilisation Unit, February 2018 The M23 militants were pushed into Uganda, where M23 leader Sultani Makenga and hundreds of fighters surrendered.11France 24, ‘M23 rebel commander surrenders to Uganda,’ 7 November 2013

Following the defeat of the M23, political violence events involving M23 militants declined, with few reported cases in subsequent years. However, the M23 re-emerged as a prominent conflict actor in late 2021, leading to a nearly thirty-fold increase in activity in 2022 compared to the year prior. Amidst the myriad conflicts across DRC, the M23 became the second most active non-state armed group in 2022, behind the Allied Democratic Forces, and the most active non-state armed group in Nord Kivu province.

UN investigations, foreign governments, and human rights groups have linked the previous offensives and the re-emergence of the M23 in 2021 to support from Rwanda.12UN Security Council, ‘Letter dated 16 December 2022 from the Group of Experts on the Democratic Republic of the Congo addressed to the President of the Security Council,’ 16 December 2022; Human Rights Watch, ‘DR Congo: Atrocities by Rwanda-Backed M23 Rebels,’ 6 February 2023 The current government of Rwanda has a long history of involvement in eastern DRC, dating back to the Congo Wars in the mid to late 1990s when Rwandan forces pursued suspected genocidaires into DRC. Rwandan President Paul Kagame and his administration have made several speeches concerning the mistreatment of Rwandophones in DRC and the atrocities of the rebel Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda (FDLR), which may undergird Rwandan intervention.13Charles Onyango-Obbo, ‘Kagame: DRC has crossed red line, war won’t be in Rwanda,’ The East African, 26 February 2023; Musinguzi Blanshe, ‘Rwanda & DRC accuse each other of using rebel groups to their advantage,’ The Africa Report, 10 June 2022 Other analysis notes the additional military and economic interests of Rwanda in backing M23 militants as a proxy war against Uganda.14Africa Center for Strategic Studies, ‘Rwanda and the DRC at Risk of War as New M23 Rebellion Emerges: An Explainer,’ 29 June 2022 Indeed, M23 operations have elevated hostilities between DRC and Rwanda, including a spike in political violence events involving the Rwandan military (RDF) in DRC in 2022.

This report tracks M23 activity and areas of operations in Nord Kivu province during the latest M23 offensive that began in late 2021. The following section examines the primary conflict actors engaged by the M23 and explores the ways in which the M23’s activity may progress.

Activity and Area of Operation

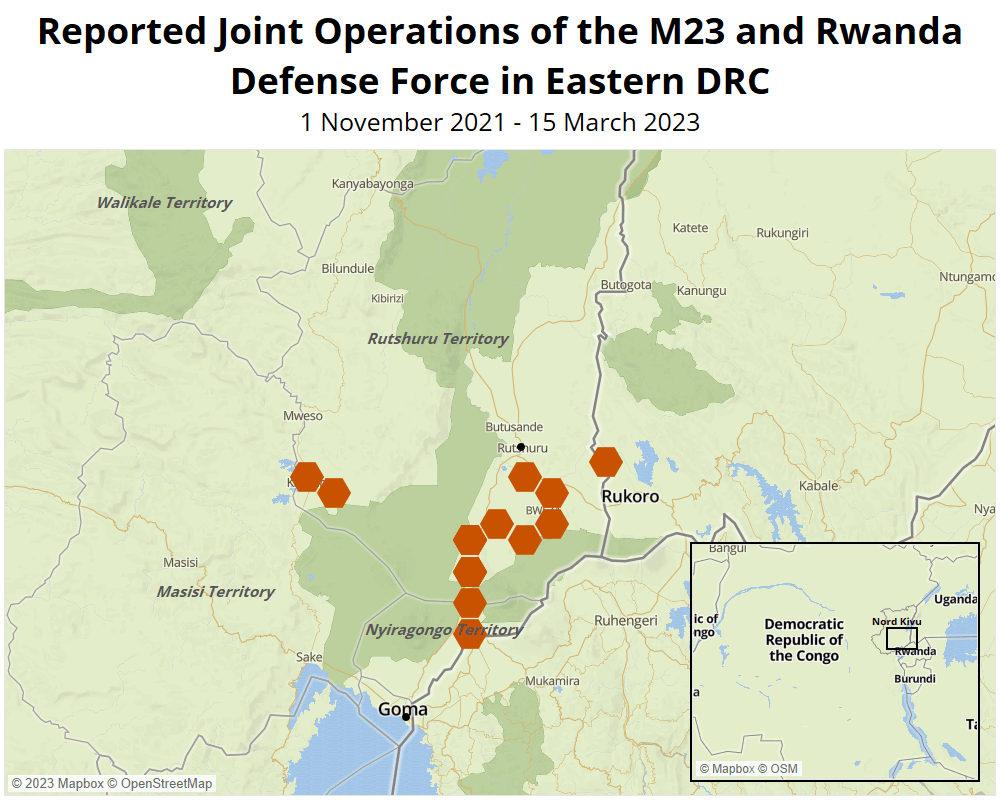

Following years of sporadic violence after their defeat in 2013, the M23 initiated an offensive against Congolese military forces and allied militias in November 2021. While fighting was initially concentrated around southeast Rutshuru territory, the M23 developed a clear southern push towards Goma and later radiated north and west of their initial positions (see map below).

Expansion of M23 Violence in Eastern DRC

1 November 2021 - 15 March 2023

In November 2021, the M23 began clashing with the FARDC and other FARDC-aligned armed groups in Bwisha chefferie (chiefdom), Rutshuru territory. The M23 initiated a southward offensive towards Goma in January 2022, continuing to clash with FARDC around Butaka and moving further south into Bukumu chefferie of Nyiragongo territory by May 2022. Amid the fighting, the M23 captured some strategic FARDC military bases, including Rumangabo, the largest military base in Nord Kivu province.15Xinhua, ‘Roundup: M23 rebels withdraw from captured military camp in NE DR Congo,’ 7 January 2023 After June 2022, the number of recorded political violence events fell for several months until a renewed push started in October. Then, the theater of operations extended to Bwito chefferie in western territory, alongside reported clashes further north at the border town of Kitagoma.

November 2022 marked a significant turning point for M23’s violence, with expansion in multiple directions north and west, and fighting just north of Goma. By December 2022, the UN reported that the M23 controlled around three times the amount of territory held in March of the same year.16UN Security Council, ‘Letter dated 16 December 2022 from the Group of Experts on the Democratic Republic of the Congo addressed to the President of the Security Council,’ 16 December 2022, p.9 Despite over a hundred active non-state armed groups in DRC, ACLED data show that the M23 was the most successful rebel group in overtaking territory in DRC last year.

The M23 has continued to contest territory into the first quarter of 2023. In an ongoing push towards Goma, a new fighting front developed deep into Masisi territory in January and February 2023, with clashes reported as far west as Osso and Bahunde. The western fighting allowed the M23 to control western trade routes from Goma, reaching Sake town, 15 kilometers west of Goma.

Strategic and Unusual Alliances

The alliances between armed groups supporting or suppressing the M23 remain a central point of contention between the Congolese and Rwandan governments, elevating the profile of ethnic and regional dimensions to the conflict.17Brian Sabbe, ‘Why M23 is not your average rebel group,’ International Peace Information Service, 6 February 2023; Africa News, ‘RDC : plusieurs milices luttent contre les rebelles du M23,’ 14 December 2022 Some armed groups fighting alongside the FARDC in Nord Kivu are composed of ethnic Hutu, notably the FDLR and various Nyatura militias, providing an ethnic contrast to the primarily Tutsi militants within the M23 ranks.18Human Rights Watch, ‘DR Congo: Army Units Aided Abusive Armed Groups,’ 18 October 2022; Human Rights Watch, ‘DR Congo: Atrocities by Rwanda-Backed M23 Rebels,’ 6 February 2023 On 8-9 May 2022, several of these armed groups and FARDC leaders met in Pinga to formalize a pact against the M23, called the Patriotic Coalition.19HRW, ‘DR Congo: Army Units Aided Abusive Armed Groups,’ 18 October 2022 These alliances, especially with the FDLR, are frequently cited by the Rwandan government as a justification for involvement in the region.20Musinguzi Blanshe, ‘Rwanda and DRC accuse each other of using rebel groups to their advantage,’ The Africa Report, 10 June 2022 The FARDC also continued to fight alongside UN peacekeepers and turned to the East African Community (EAC) in September 2022 to form a regional force of troops with contingents from member countries.21EAC, ‘DRC President presides over signing of Agreement giving greenlight to the deployment of the EAC Joint Regional Force,’ 9 September 2022 The strategic alliances and integration of former rebel combatants within the FARDC make identification of separate allied armed groups difficult during conflict, with ACLED data showing that the FARDC has been joined by non-state actors in less than 10% of clashes against the M23.

Contrasting the various partnerships of the FARDC, the RDF has been the only reported partner of the M23. The RDF had reportedly supported the M23 in 2012 and 2013, along with previous backing of the former iteration of the M23, the CNDP militia.22Jason Stearns, ‘From CNDP to M23: The Evolution of an Armed Movement in Eastern Congo,’ Rift Valley Institute, 2012’ UN Security Council, ‘Letter dated 19 July 2013 from the Chair of the Security Council Committee established pursuant to resolution 1533 (2004) concerning the Democratic Republic of the Congo addressed to the President of the Security Council,’ 29 July 2013 UN reports document aerial footage, photographs, and FARDC testimony of soldiers wearing RDF uniforms based in M23 camps in DRC.23UN Security Council, ‘Letter dated 16 December 2022 from the Group of Experts on the Democratic Republic of the Congo addressed to the President of the Security Council,’ 16 December 2022, p. 11 – 12 Since May 2022, the M23 has also engaged in mortar and artillery shelling, with the increasing military capacity providing further evidence of Rwandan support.24HRW, ‘DR Congo: Resurgent M23 Rebels Target Civilians, 25 July 2022 Given the M23’s use of Rwandan military uniforms and equipment, sources tend to vary concerning the number of joint M23 and RDF violent events.

However, Human Rights Watch cites unpublished reports by the Expanded Joint Verification Mechanism, a group of military experts from member states of the International Conference on the Great Lakes Region, that document the arrest of RDF soldiers in DRC and foreign materiel not used by the FARDC that were left behind following battles with the M23 in Rumangabo and Kibumba.25HRW, ‘DR Congo: Resurgent M23 Rebels Target Civilians, 25 July 2022 Despite Kigali’s repeated denial of support for the M23, growing evidence from multiple sources makes this difficult to contest. According to ACLED data, based on nearly 100 international, national, subnational, new media, and other sources covering the DRC, the RDF reportedly fought alongside the M23 over a dozen times throughout 2022 and early 2023, primarily in Rutshuru and Nyiragongo territories (see map below).

Changing Conflict Dynamics: Ongoing Battles and Rising Violence Targeting Civilians

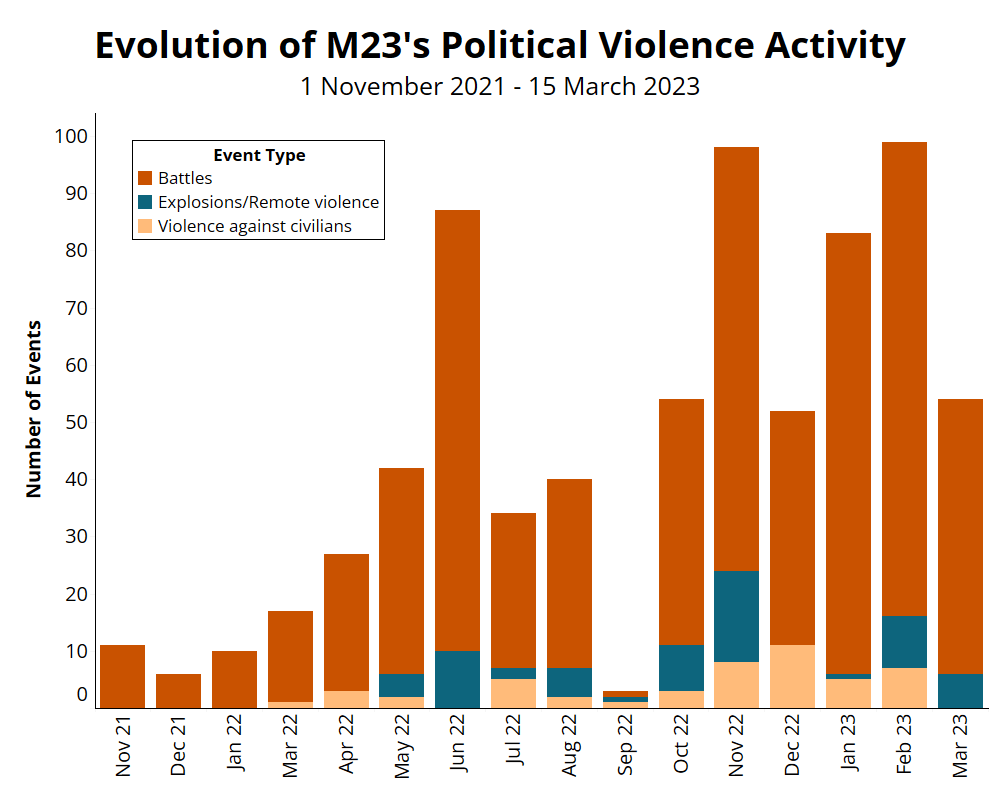

Since the resurgence of the M23 in November 2021, most M23 activity has involved battles (see graph below). The majority of battles have been fought solely against the FARDC, with sporadic fighting against other local militias also recorded in Rutshuru territory and surrounding areas. The Congolese military has responded to the M23 operations with aerial strikes using fighter jets as part of joint ground operations, as well as some isolated cases of aerial bombardments in June and November 2022. During these aerial bombardments, three alleged cases of the Rwandan military shelling Congolese military planes triggered increased tensions between the two countries. While the fighting between the M23 and FARDC continues to be a form of indirect confrontation with Rwanda, the shelling of the planes brought the two countries into a high-profile direct confrontation. While Rwanda claimed the military planes had crossed the border into Rwanda, the Congolese government affirmed that the fighter jets remained in domestic airspace.26 International Crisis Group, ‘A Dangerous Escalation in the Great Lakes,’ 27 January 2023

Although the overwhelming majority of its armed activity has involved clashes with the FARDC, M23 operations have also had a significant impact on civilian populations. Indeed, significant civilian fatalities have occurred during clashes between the M23 and FARDC, poignantly exemplified by the fighting in the Bambu groupement of Rutshuru territory from 29 November to 1 December 2022, during which the M23 reportedly killed numerous civilians.27Africa News, ‘UN Revises Toll from DR Congo’s Kishishe Massacre to 171,’ 7 February 2023; Christoph Vogel and Judith Verweijen, ‘How to avoid false narratives around DR Congo’s M23 conflict,’ The New Humanitarian, 23 January 2023 Since April 2022, the M23 has also actively targeted civilians outside of battle events, though at lower levels than 2012-13. Between 1 November 2021 to 15 March 2023, the total number of reported fatalities from M23 activity surpassed 750, with at least 134 fatalities recorded during targeted attacks on civilian populations, in addition to civilians killed during and in the immediate aftermath of fighting that occurred around Kishishe in the Bambu groupement. Moreover, M23 activity has led to the mass displacement of civilians. The UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs reported in December 2022 that over 500,000 people had fled from the fighting in Nord Kivu province in connection with the M23.28UNOCHA, ‘Displacement trends: Crisis affecting Rutshuru – Nyiragongo – Lubero,’ 20 December 2022

Since November 2021, civilian targeting has made up 10% of the M23’s total political violence activity, compared to over a third of the group’s total political violence events in 2012-13. During the previous offensive, M23 actions targeting civilians coincided with broader fighting and occurred in the same areas as battles with military forces. Contrastingly, civilian targeting during the M23’s current offensive often follows battles with the FARDC. Violence targeting civilians rose in the M23’s strongholds around Rutshuru territory, where the M23 took control of areas from FARDC and other local militias. Some cases of violence targeting civilians also moved southward and westward following the M23’s broader offensives. As the area controlled by M23 expanded, a rise in violence targeting civilians coincided and peaked in December.

Despite the aforementioned occurances, the overall lower levels of civilian targeting may be a shift in M23 strategy towards building stronger local legitimacy among civilians in areas under their control.29The provision of security and limiting civilian targeting may be understood as way for the M23 to increase their perceived legitimacy amongst local populations. See Florian Weigand, ‘Working Paper: Investigating the Role of Legitimacy in the Political Order of Conflict-torn Spaces,’ SiT: London School of Economics and Political Science, April 2015 Since 2012, the M23 established local administrators to govern civilian affairs and attempted to foster a positive public image and attract support.30Melanie Gouby, ‘What Does the M23 Want?’ Newsweek, 3 December 2012 M23 leaders cited the challenges of ongoing governance as a reason for withdrawing from Goma in 2013.31Jeffrey Gettleman, ‘Rebels Pull Out of Strategic City in Congo,’ New York Times, 1 December 2012 This may have prompted changes in the current offensive to enhance local legitimacy and ease the burden of ongoing control of territory. Reducing civilian targeting permits the perception of the M23 as an alternative authority to the FARDC,32Zachariah Cherian Mampilly, ‘Rebel Rulers : Insurgent Governance and Civilian Life during War,’ Cornell University Press, 2012 especially given the latter’s use of violence targeting civilians has been 5% higher than that of the M23 during the recent offensive. The M23 has been careful to refute claims of civilian targeting through social media outlets and point back to failures of the Congolese government and FDLR.33Christoph Vogel and Judith Verweijen, ‘How to avoid false narratives around DR Congo’s M23 conflict,’ The New Humanitarian, 23 January 2023 Lower levels of civilian targeting may also bolster bargaining power with international actors involved in negotiations with the M23.34Coggins explores the concept of rebel diplomacy, connecting the violent and non-violent practices of a rebel group with the tactics of negotiating with external actors. See Bridget L. Coggins, ‘Rebel Diplomacy: Theorizing Violent Non-State Actors’ Strategic Use of Talk,’ in Rebel Governance in Civil War, Cambridge University Press, 2015

The rise in violence targeting civilians corresponded with looting and property destruction activity, the first cases arising in Rutshuru territory in June 2022 before reports also emerged in Masisi and Nyiragongo later in 2022 and 2023. The M23 has generated revenue and supplies by stealing food from farms and schools, supplies at health centers, and other goods from local shops. The M23 has also raised funds by taxing civilians in areas under their control, including the strategic Bunagana border crossing to Uganda.35UN Security Council, ‘Letter dated 16 December 2022 from the Group of Experts on the Democratic Republic of the Congo addressed to the President of the Security Council,’ 16 December 2022, p.10 – 11 Taxation by establishing armed roadblocks has been a prolific method of revenue generation by armed groups in the DRC,36Peer Schouten, ‘It’s the Roads, Stupid,’ Foreign Policy, 12 June 2021 reportedly the primary income generator of the M23 during the 2012-13 offensive.37Jason Miklian and Peer Schouten, ‘Fluid Markets,’ Foreign Policy, 3 September 2013

Looking Forward

M23 activity continues to grow in Nord Kivu province without clear indicators of a cessation of hostilities in the coming months. The ongoing expansion of the M23, failed ceasefires, and defections from the FARDC to the M23, including the high-profile case of Colonel Bahati Gahizi and Lt. Col. Frank Kavujobwa in February 2023, collectively point towards a continuation of M23 operations.38Kim Aine, ‘DRC Army Colonels Defect to M23 Movement,’ Chimp Reports, 2 February 2023; Will Ross, ‘DR Congo’s M23 ceasefire: Angola to deploy troops after failed truce,’ BBC, 12 March 2023 Ending the escalation of violence will likely require diplomatic and military operations between Kinshasa and both the M23 and Rwandan government. While Kigali continues denying involvement with the M23, the recent rise in confrontations between the FARDC and RDF requires cooperation between the two countries to de-escalate the situation.

The most likely intention of the M23 is to retake Goma, a strategic economic hub and a target of their previous offensive in 2012-13.39Aurélie Bazzara-Kibangula et al, ‘In DR Congo, M23 rebel threat looms over city of Goma,’ France 24, 22 December 2022 Many factors point to this aim, including a southward M23 offensive directly towards Goma, nearby westward fighting that has reached Sake town, and evidence of the M23’s economic interests in Nord Kivu, with fighting in surrounding areas serving to cut regional supply routes for the region. Western offensives may also reduce the ability of goods to be supplied from other Congolese roadways and force dependence on trade routes from Rwanda.40Africa News, ‘DR Congo: M23 rebels tighten economic vice around eastern North Kivu province,’ 21 December 2022 So far, the M23 has largely cut supply routes from Uganda along the RN2 road. However, as the challenges of ongoing governance led the M23 to previously withdraw from the city, this may pose similar challenges in the future.41Jeffrey Gettleman, ‘Rebels Pull Out of Strategic City in Congo,’ New York Times, 1 December 2012 In addition to Goma, the northern and western movement of M23 militants from Rutshuru territory may also lead to hostilities in other areas of Nord Kivu province and a broader area of insecurity.

Violence targeting civilians has the potential to escalate as the M23 takes control of further territory and undertakes forms of governance, as exemplified by higher levels of violence against civilians during the M23 offensive in 2012-13. In addition, the taxation and looting of civilians will likely continue as a form of revenue for the M23. In areas held by the FARDC, civilians suspected of collaborating with the M23 and Rwandophones may also face increasing forms of violence.

The popularity of international forces diminished in Nord Kivu province, evidenced by a growing number of demonstrations against UN peacekeepers and EAC regional forces last year. However, regional military cooperation and UN peacekeepers may be able to quell the M23 offensive, as was the case in 2013. Additional military forces may strengthen this effort, with Angola and Burundi promising additional troops for the fight against the M23.42Will Ross, ‘DR Congo’s M23 ceasefire: Angola to deploy troops after failed truce,’ BBC, 12 March 2023; Edmund Kagire, ‘Burundi To Deploy Troops in DRC As Part of EAC Regional Force,’ KT Press, 3 March 2023

Visuals in this report were produced by Christian Jaffe and Danny Lord.