Political Repression in Cuba Ahead of the 2023 Parliamentary Elections

23 March 2023

On 26 March 2023, voters will elect 470 deputies to Cuba’s National Assembly of People’s Power, who, in addition to fulfilling legislative functions during their five-year term, will be nominating Cuba’s next head of state. The government has characterized Cuba’s political system as a grassroots democracy, where candidacies to the parliament largely emerge from municipal authorities and are approved by the National Candidate Commission, a body composed of social organizations, such as labor unions and student associations.1International Foundation for Electoral Systems, ‘Election for Cuban National Assembly of People’s Power,’ 2023; Al Jazeera, ‘Cuban opposition calls on voters to skip upcoming local elections,’ 24 November 2022

In practice, however, Cuba’s electoral process has been criticized for blocking the opposition’s access to power. Notably, the Council for Democratic Transition in Cuba, a platform created by opposition members to promote pluralism, freedom, and human rights, has called voters to boycott the upcoming elections after pro-government supporters reportedly prevented several opposition candidates from running in the November 2022 municipal elections.2CiberCuba, ‘Candidato independiente logra nominación a elecciones municipales en Cuba,’ 22 November 2022; Ivette Pacheco, ‘Activistas promueven campaña “Yo me abstengo” con vistas a elecciones del 26 de marzo en Cuba (VIDEO),’ Radio Televisión Martí, 6 March 2023

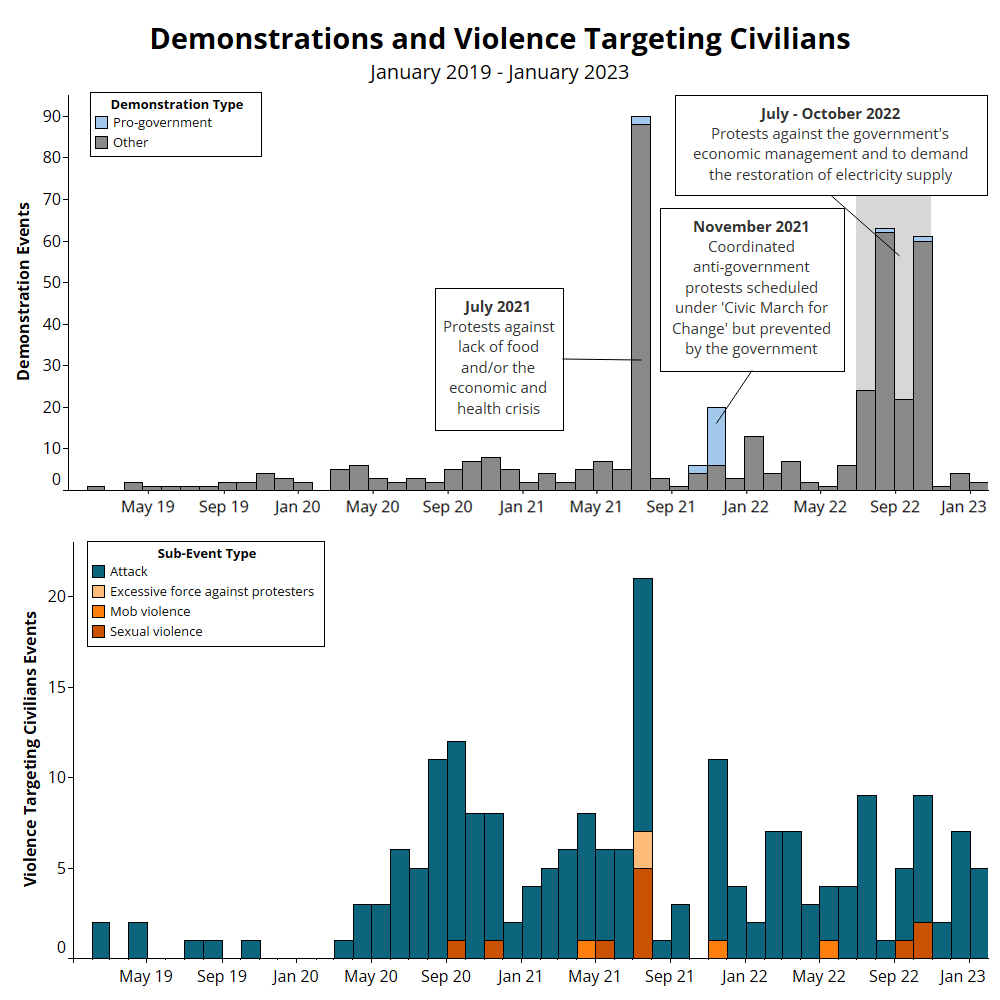

Criticism of Cuba’s political restrictions ahead of the 2023 electoral process takes place against a backdrop of anti-government mobilization and state repression of dissenting voices during the mandate of incumbent President Miguel Díaz-Canel. In 2021, the state responded to an historic surge in demonstration activity prompted by shortages of basic goods and COVID-19 restrictions, targeting activists and opposition figures for retaliation.3Observatorio Cubano de Derechos Humanos, ‘2021 – Detenciones Arbitrarias,’ 202 The government is also set to harden the crackdown on dissent with a new penal code that came into force in December 2022. The code criminalizes those “endangering the functioning of the State and the Cuban government,” the sharing of “fake information” online, and the intentional offending of another person.4Amnesty International, ‘Cuba: New criminal code is a chilling prospect for 2023 and beyond,’ 2 December 2022

This report explores the main demonstration and political violence trends in Cuba since 2018, and highlights the key challenges shaping the country’s upcoming elections. It finds that the government has used a combination of repressive tactics in an effort to quell growing frustration and dissent amid socio-economic hardship, including the targeting of civil society and opposition members, an increasing use of violence against civilians during periods of heightened demonstration activity, a resurgence of violent pro-government actors, and heightened levels of arrests and short-term detentions.

Unaddressed grievances and repression might lead to lower voter turnout in the upcoming elections, which could, in turn, further undermine the legitimacy of Cuba’s next government. The election results will be unlikely to trigger immediate demonstrations because deputy candidates run alone in each jurisdiction, leaving little doubt about the outcome of the vote. However, should the new parliament fail to provide solutions to the country’s economic challenges, long-term anti-government mobilization will likely continue to mount. Amid ongoing suppression of the opposition, the parliamentary elections will also be unlikely to bring about increased political freedom, as Cuba’s highest power continues to be vested in the First Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party, a position held by President Díaz-Canel since 2021. Expressions of dissent among the opposition could result in yet more state repression.

Opposition Mobilization and State Repression

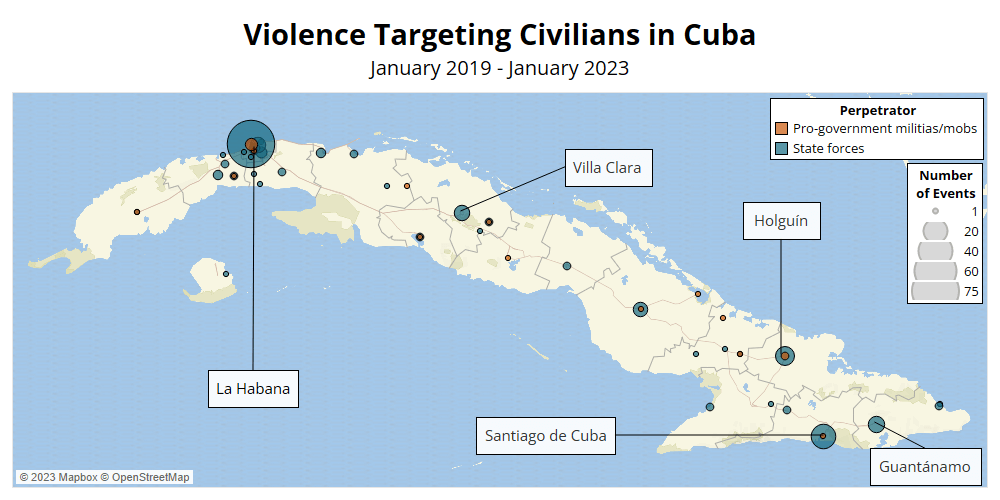

Between January 2019 and March 2023, ACLED records more than 200 incidents of violence targeting civilians in Cuba. Violence has taken place across the country but mostly in the capital region, with attacks on civilians typically increasing along with increases in demonstration activity. At least one person was beaten to death by police in this period during the violent repression of an anti-government protest in the town of Batabano on 12 July 2021. On the same day, in Arroyo Naranjo, another demonstrator died during clashes with state forces. In light of severe restrictions on press freedom in the country, these incidents are unlikely to be isolated cases, but rather indicative of a larger pattern of repression in Cuba.

State forces are the leading perpetrator of this violence and have principally targeted members of dissident civil society organizations, opposition groups, and journalists for their coverage of human rights violations. Ladies in White, the Patriotic Union of Cuba, the San Isidro Movement, and the Opposition Movement for a New Republic are among the groups most frequently targeted for their opposition to the government. These groups have advocated for a wide range of changes and reforms, from the release of political prisoners to increased freedom of expression and pluralism.

Despite a government decree prohibiting all forms of opposition against the government and the entry into force of Cuba’s new penal code, civil society organizations have continued to criticize the regime ahead of the parliamentary elections, including by launching a campaign calling on Cubans to abstain from voting to delegitimize the results and push for change.5Diario de Cuba, ‘Campaña ‘Cuba dice NO a la dictadura’, un llamado a la abstención en las votaciones de marzo,’ 17 January 2023 While few events of physical violence have been reported in the days immediately leading up to the poll, state forces have reportedly called in multiple activists participating in the campaign and taking part in election observation activities for questioning.6Ivette Pacheco, ‘Denuncian amenazas a los activistas que promueven abstención en elecciones del 26 de marzo en Cuba,’ Radio Televisión Martí, 20 March 2023

Continued repression ahead of the vote is part of a larger crackdown on opposition voices that has intensified in recent years. In 2021, a wave of popular protests against worsening living standards prompted a violent government response (see graph below).714ymedio, ‘Con una inflación siete veces superior al aumento del salario, la pobreza se extiende en Cuba,’ 3 March 2023 The Cuban government ordered the arrests of demonstrators and opposition activists, in addition to the use of lethal force against protesters in Mayabeque. Similarly, in November, civil society organizations attempted to organize the ‘Civic March for Change,’ a countrywide protest calling for civil rights and the release of political prisoners, which the government sought to discourage through the targeted use of violence against civilians.8Jessica Domiguez and Jesús Arencibia, ‘El drama de la comida en Cuba,’ El Toque, 2021

Repression continued into 2022 and spiked in July, when the government suppressed popular mobilization commemorating the July 2021 demonstrations and calling for the release of political prisoners. Civilian targeting also increased in October with the onset of mobilization against widespread power blackouts caused by the country’s aging and underfunded electricity grid infrastructure and damage from Hurricane Ian in September.9Andrea Rodríguez, ‘Small protests appear in Havana over islandwide blackout,’ Associated Press, 30 September 2022

While state forces remained the main perpetrators of political violence targeting civilians in Cuba in 2022, they have also counted on the support of a countrywide network of pro-government groups, such as Rapid Response Brigades, to attack opposition members and conduct ‘acts of repudiation’ (see map below). Acts of repudiation first emerged in Cuba in the 1980s, involving mobs of government supporters shaming individuals who did not adhere to the precepts of the revolution by shouting insults, throwing eggs or litter, and sometimes physically assaulting their target.10Yadiris Luis Fuentes, ‘Actos de repudio: una forma de represión de las disidencias políticas en Cuba,’ Distintas Latitudes, 6 December 2021 Since 2020, ACLED data indicate that acts of repudiation have gained new momentum. While the groups are not officially coordinated by the state, civil society organizations claim that they are backed by the government.11Amnesty International, ‘Cuba: Tactics of repression must not be repeated,’ 5 October 2022 The actions of these citizen groups have allowed the government to project popular support, while distancing itself from certain acts of repression.

Alongside the direct use of violence, the Cuban state has additionally resorted to arbitrary arrests and house detentions to silence dissent, particularly in 2021.12Observatorio Cubano de Derechos Humanos, ‘2021 – Detenciones Arbitrarias,’ 2021 Human rights organizations report that state forces detain members of the opposition without due process, hold them incommunicado for extended periods of time, and prevent them from accessing legal representation.13Amnesty International, ‘Amnesty International Report 2021/22: The State of the World’s Human Rights – Cuba 2021,’ 2022; Human Rights Watch, ‘World Report 2021: Cuba Events of 2020,’ 2021 Detentions often give rise to outright violence. ACLED data show that a significant share of all reported incidents of violence targeting civilians are directed specifically at prisoners and detainees, with at least two deaths in custody. Prison guards have been accused of beating and humiliating detainees – notably through forced stripping – in retaliation for their activities or complaints against detention conditions.14Human Rights Watch, ‘Prison or Exile: Cuba’s Systematic Repression of July 2021 Demonstrators,’ 11 July 2022 State forces also temporarily arrest individuals to prevent them from participating in demonstrations or meetings, such as the detention of prominent activists in November 2021 to impede the ‘Civic March for Change.’ Ahead of the November 2022 municipal elections, law enforcement arrested an opposition member and prevented them from registering as a candidate.15CiberCuba, ‘Candidato independiente logra nominación a elecciones municipales en Cuba,’ 22 November 2022 Harassment and continuous arrests have, however, most particularly targeted leaders of civil society organizations, with state forces arresting Berta Soler, leader of Ladies in White, at least 42 times since 2021 to date.

Looking Forward

The rise of popular discontent linked to socio-economic hardship led to record abstention rates during the November 2022 local elections.16Mauricio Vicent, ‘La alta abstención marca un nuevo escenario político en Cuba,’ El País, 28 November 2022 While President Díaz-Canel has acknowledged the difficulties faced by the Cuban population, opposition groups claim he has failed to address the country’s economic problems, warning that 2023 could bring even greater challenges.17Diario de Cuba, ‘Díaz-Canel a los cubanos: 2023 ‘podría ser aún más difícil’, pero ‘más atractivo para el que se sienta revolucionario,’ 2 January 2023

With the end of the economic crisis nowhere in sight, voters could – similarly to the November 2022 local elections – demonstrate their dissatisfaction at the polls, with social organizations continuing to promote abstention. Although a high abstention rate would likely have little impact on the final voting outcome, it could confer the National Assembly of People’s Power and the future president – to be nominated by the incoming parliament – less legitimacy before the population and provide an indication of overall levels of popular dissatisfaction.

Regardless of voter turnout, the election results will be unlikely to prompt significant political change or immediate demonstrations, with many among the electorate disillusioned with the country’s electoral system. Persisting socio-economic challenges, however, will continue to weigh on a new parliament and could lead to demonstrations. Despite Cuba’s repressive environment, which has prompted a rise in dissidents taking up exile abroad,18James Clifford Kent, ‘Cuba: why record numbers of people are leaving as the most severe economic crisis since the 1990s hits – a photo essay,’ The Conversation, 17 February 2023 civil society groups continue to call for freedom of expression and pluralism.19Ed Augustin, ‘As independent media blossoms in Cuba, journalists face a crackdown,’ The Guardian, 20 January 2023 Coming into the next parliamentary term, state repression will likely continue unabated and could even escalate with the implementation of the country’s new penal code, which criminalizes and limits anti-government activity, including digital activism.20Amnesty International, ‘Cuba: New criminal code is a chilling prospect for 2023 and beyond,’ 2 December 2022

Visuals in this report were produced by Ana Marco