Anti-Government Demonstrations in Iran

A Long-Term Challenge for the Islamic Republic

12 April 2023

Iran was rocked by mass demonstrations triggered by the September 2022 death of Mahsa Amini — a young Kurdish woman — while in the custody of the Guidance Patrol (also known as the ‘morality police’) for allegedly violating the hijab dress code. Protests over the mandatory hijab rule soon coalesced around a wide range of grievances with the regime, with participants demanding protections for civil, political, and human rights and calling for an end to the Islamic Republic. Although street demonstrations have subsided for the time being, how the protest movement will evolve — and how it will impact the stability of the Islamic Republic — remains an open question.

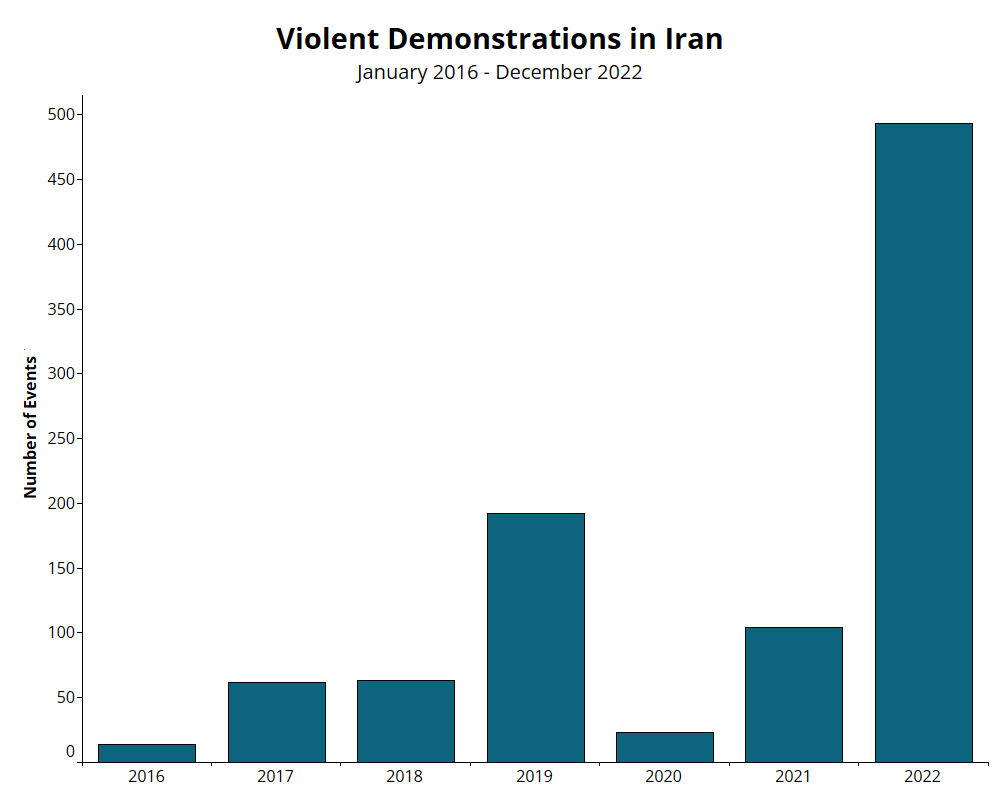

This report explores potential answers to this question by examining notable trends and implications of the wave of demonstrations that unfolded in the country between September and December 2022. It argues that several emerging aspects of the nationwide movement may pose a long-term challenge to the regime. The demonstrations following Amini’s death were not only unique in regard to their geographical spread and longevity, but also in the way they brought together different segments of society with both distinct and overlapping grievances. Moreover, amid a harsh crackdown by Iranian authorities, engagement in violence by demonstrators has trended upward: between mid-September and December 2022, ACLED records the highest number of violent demonstration events for any round of nationwide demonstrations in Iran since the beginning of data collection in 2016. The increased use of Molotov cocktails and the killing of dozens of security personnel are among the most significant trends in demonstration violence observed in the latest round of events.

The demonstrations did not reach a critical mass necessary to pose an immediate threat to the survival of the regime. Yet, this latest round in a sequence of increasingly violent demonstrations is indicative of growing resentment in Iranian society against the ruling elites and a willingness to express it forcefully despite severe repression. As the regime refuses to reform, the growing frequency and intensity of demonstrations suggests that the government will find itself in an increasingly unstable domestic position and increasingly isolated in the international arena.

Months of Widespread Demonstrations Cut Across Different Sectors of Society

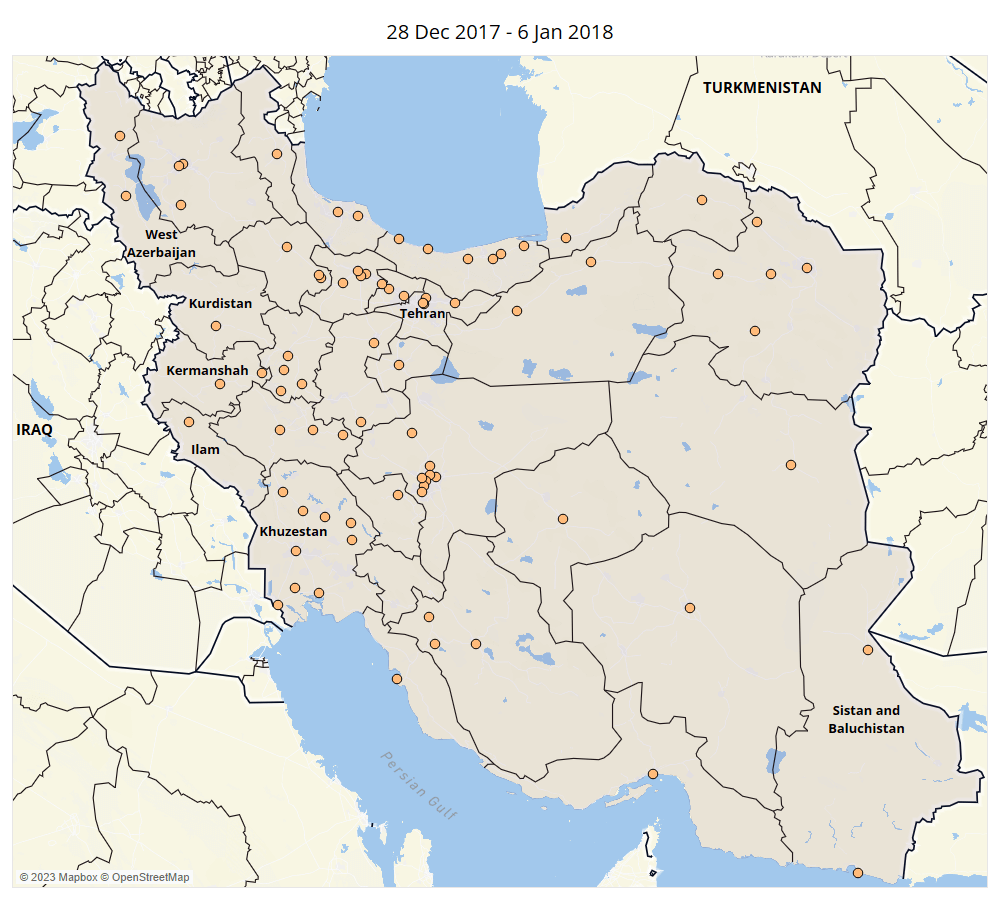

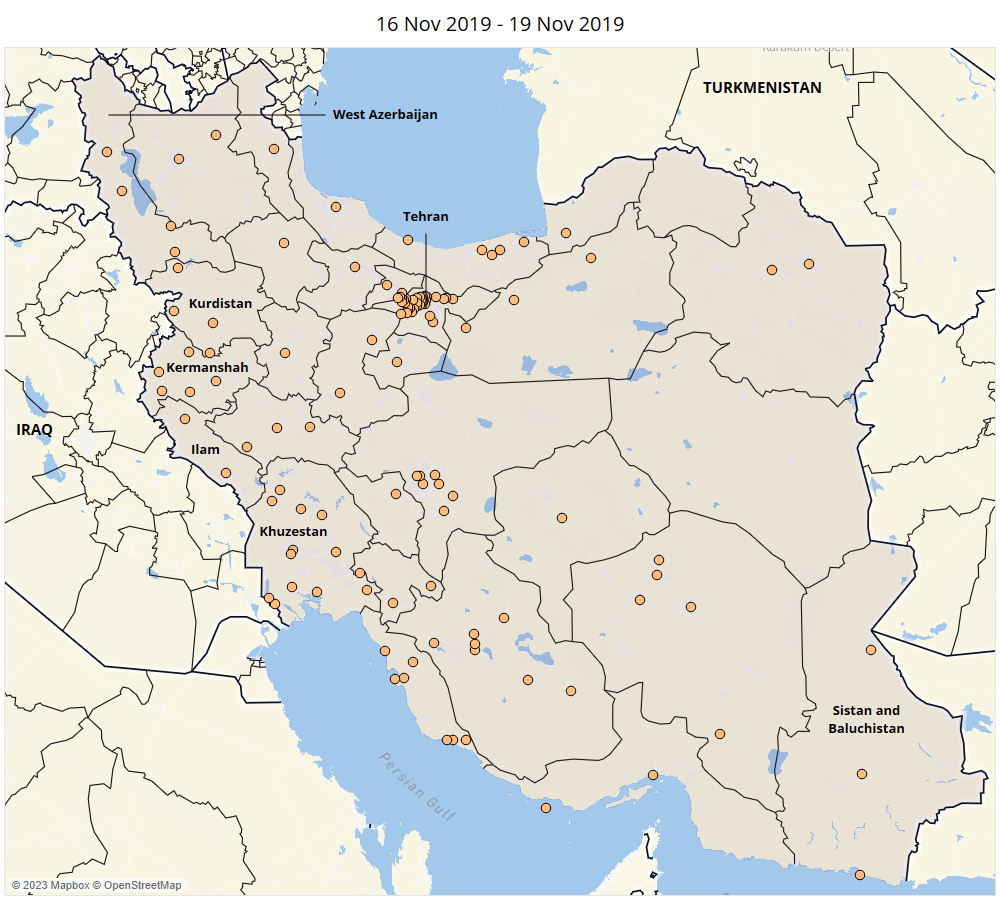

Demonstrations in Iran have been a frequent occurrence in recent years. From daily labor protests over low salaries and worsening work conditions to service-delivery protests over water shortages and inflation, Iranian authorities are confronted with thousands of demonstrations every year. Yet, demonstrations have been increasingly shifting from small-scale protests to include a more explicit rejection of the government’s authoritarian policies. The demonstrations following Amini’s death marked the third round of large-scale anti-government unrest over the last five years. Prior to 2022, a spike in food prices sparked anti-government demonstrations between late December 2017 and early January 2018, while another round of anti-government protests erupted across the country following a tripling of fuel prices in November 2019. Before this string of events, the last episode of large-scale nationwide demonstrations occurred almost a decade prior, when Iranians took to the streets in 2009 over allegations of electoral fraud as part of the Green Movement.

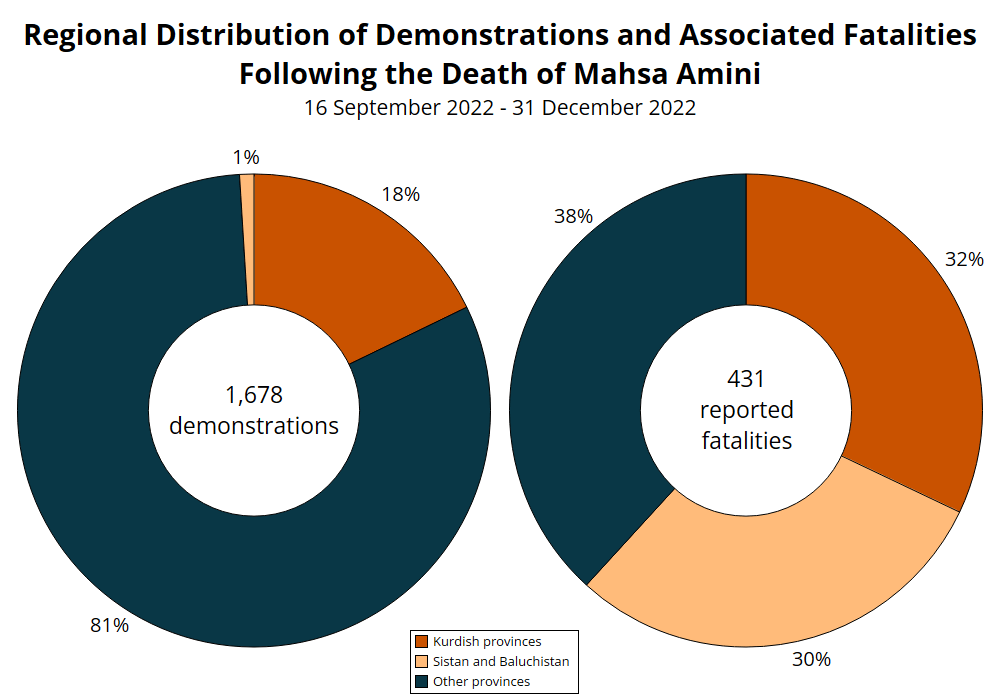

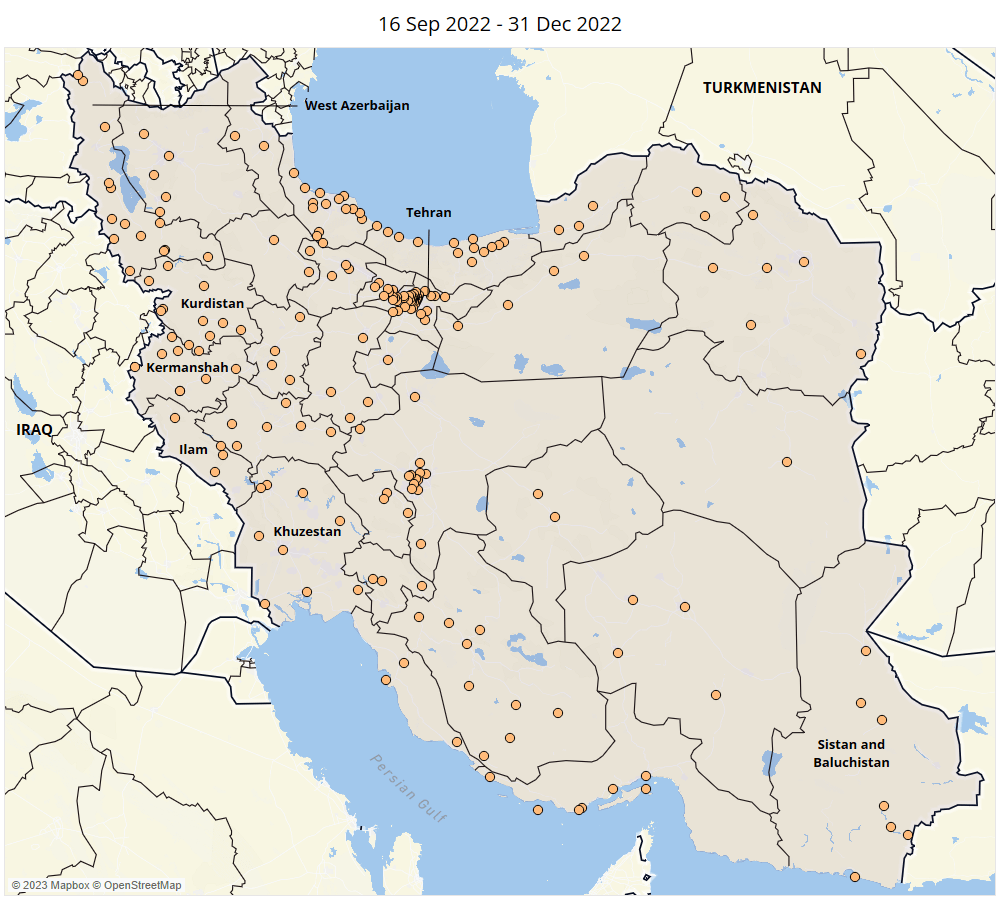

There are several important aspects regarding how nationwide demonstrations have been evolving, including geographical spread and longevity. During the 2017-2018 wave of demonstrations, events were reported in fewer than 100 locations, while the 2019 demonstrations were reported in approximately 130 locations. With events recorded in over 210 locations, the wave of demonstrations following Amini’s death represents a significant increase in the geographical spread of unrest when compared with previous rounds (see maps below). The longevity of the recent cycle of unrest was also unprecedented, with demonstrations continuing at high levels for about three months, while the two previous rounds did not last longer than a few days.

Demonstrations During the Last Three Rounds of Anti-Government Unrest

Furthermore, in contrast to the prior two rounds, where mostly working class Iranians took to the streets over specific economic grievances, this latest round of unrest brought together different segments of society. The movement uniquely cut across class and ethnic divisions, with 300 demonstrations recorded across Iran’s Kurdish areas, over 750 demonstrations at universities and high schools, nearly 90 in the affluent northern districts of Tehran, and dozens involving members of the minority Sunni community in the impoverished eastern province of Sistan and Baluchistan. In addition, disparate segments of the Iranian diaspora, including ethnic and separatist groups, monarchists, secularists, and dissident Islamists, showed a unified front in opposition to the Islamic Republic. Across the world, hundreds of demonstrations were organized in support of the protest movement in Iran, including a rally in October with around 80,000 participants in the German capital, Berlin, believed to be one of the largest demonstrations by the Iranian diaspora in history.1 Iran International, ‘Big Iranian Rally In Berlin Rattles Regime In Tehran,’ 23 October 2022 The different segments of the Iranian diaspora have remained divided by their views on desired alternatives to the Islamic Republic, and often lack a sufficiently large support base inside Iran to enable them to play a leading role. Yet, they have been increasingly provided a platform at public fora in the United States and Europe and now have a stronger voice in demanding intensified international pressure on Iran.

Violent Demonstrations Increase

The demonstrations following Amini’s death were also significant with respect to the level of violence involving not just security forces but also demonstrators. While the 2009 Green Movement demonstrations were largely a peaceful, discontent increasingly manifested in violence during the last two rounds of demonstrations. In November 2019, violent or destructive activity was reported at almost 50% of the demonstrations. High levels of violence seem to have been the result of a spontaneous outburst of destructive activity within a few days, where demonstrators vandalized hundreds of petrol stations in reaction to the hikes in fuel prices, and set ablaze government sites and banks affiliated with the regime.

During the latest round in 2022, over 400 violent demonstration events were reported, more than any annual total recorded in Iran since ACLED coverage began in 2016 (see graph below). Use of Molotov cocktails was widespread during these events, with nearly 70 incidents reported across 23 provinces between mid-September and December 2022. Despite a lull in demonstrations, Molotov cocktail attacks have continued into 2023, with over 30 incidents recorded by early April. Increasingly defiant demonstrators also attacked Basij bases, homes and offices of security personnel and government officials, religious seminaries, and mosques. Video guides on making Molotov cocktails were circulated on Iranian social media feeds,2Christopher de Bellaigue, ‘Iran’s moment of truth: what will it take for the people to topple the regime?,’ The Guardian, 6 December 2022 while the home addresses of members of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) and Basij forces, as well as mosques used by Basijis to rest and reorganize, were reportedly published on the darknet.3Yonah Jeremy Bob, ‘IRGC, Basij militia personal information leaked online by protesters – exclusive,’ Jerusalem Post, 4 December 2022 Along with anti-riot police units, the Basij were the main forces involved in quelling the unrest across the majority of provinces, while the IRGC forces were engaged in crackdowns in Baluchi and Kurdish provinces. The Basij force is a paramilitary unit of the IRGC — a branch of the Iranian armed forces tasked with defending the regime against internal and external threats.

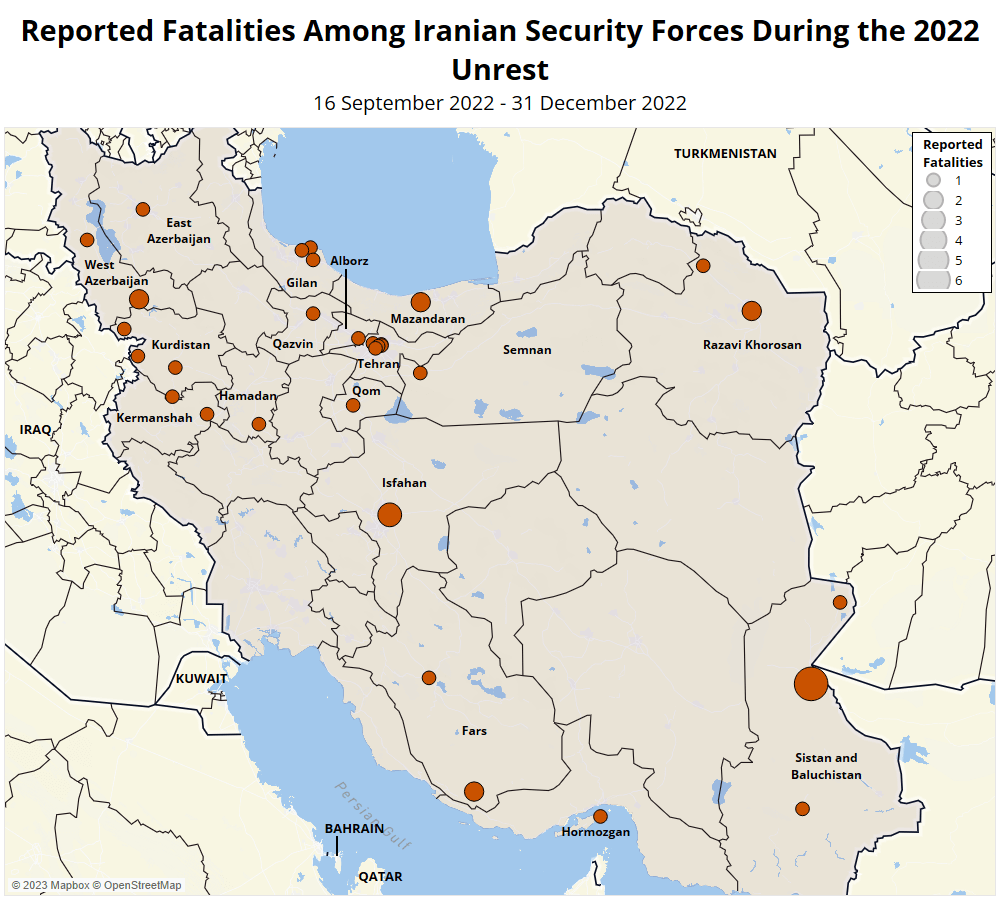

Overall, at least 46 Basij, IRGC, and police personnel were killed during violent demonstrations between mid-September and December 2022, a high figure compared with previous rounds of unrest. While many were beaten to death or killed by cold weapons, nearly half of them were killed by firearms. Additionally, over a dozen security forces were killed by firearms during armed clashes or while off-duty during the unrest. Three further attacks on security forces were reported in 2023 between January and the first week of April. This included the killing of an IRGC member with a leading role in the crackdown on demonstrators in Mahabad on 17 March,4Hengaw, ‘The killing of an IRGC force in Mahabad,’ 18 March 2023 and the shooting in early April of a security operative allegedly involved in the arrest of a demonstrator in Tehran who was later sentenced to death and executed.5Iran International, ‘Former advisor of Ahmadinejad: The Person who had arrested Mohsen Shekari was targeted with three bullets,’ 4 April 2023 The highest number of incidents involving the use of firearms were reported in Kurdish areas, which also bore the brunt of some of the regime’s harshest crackdowns (see charts below). However, it is not clear to what extent these incidents were linked to organized armed groups.

No group has claimed responsibility for these events, and armed opposition groups have rejected any accusations of involvement. Iranian authorities, though, accuse Kurdish armed groups in northern Iraq of smuggling weapons into the country and fomenting unrest, claiming to have seized over 8,000 weapons, including more than 6,000 combat weapons, since the start of the unrest.6Mehr News, ‘The report over recent unrest’s martyrs has been published’, 7 March 2023 Also, former United States National Security Advisor John Bolton suggested in an interview in November 2022 that “the opposition” inside Iran was armed with weapons stolen from Basij forces, as well as smuggled across the Kurdish border.7Twitter @bbcpersian, 7 November 2022 The reported use of firearms in central parts of Iran (e.g., Isfahan, Hamadan, Qazvin, and many others, as illustrated in the map below) signifies a novel trend regarding the escalation of such violence beyond border areas.

It should also be noted that many people own weapons in traditionally tribal areas, including the Baluchi and Arab border regions.8Farzin Nadimi and Patrick Clawson, ‘Violence in Iran’s Uprising: What Happens If Either Side Escalates?,’ The Washington Institute, 8 December 2022 The gunman involved in the deadliest event with respect to both civilian and security personnel fatalities on 30 September in Zahedan — despite initial claims by Iranian authorities regarding the involvement of Jaysh al-Adl — was a Baluchi individual with no known political affiliation. He is believed to have engaged in the firefight with IRGC forces following the spread of the violence into the city after security forces opened fire on demonstrators and worshippers earlier in the day.9Iran Human Rights Documentation Center, ‘Bloody Friday in Zahedan,’ 19 October 2022

A Crisis Weathered?

Nationwide demonstrations largely faded away in 2023, and there are no signs that the Iranian regime faces an immediate threat of collapse. The latest round of demonstrations did not evolve into an organized movement, lacking coordination, leadership, and strategy. While the movement enjoyed support from wider society, the numbers of those demonstrating have remained small.10Ali Ansari,‘Failures of Imagination,’ Comment is Freed, 16 November 2022 The older generation, many of whom had participated in the Green Movement demonstrations in pursuit of narrower political demands, largely stayed off the street. With the absence of leadership offering a concrete political roadmap for the future and a viable alternative to the Islamic Republic, many remain wary of demands for an end to the regime, particularly those who have lived through the last revolution and seen its consequences. Fears of civil war and insecurity similar to the situation in Syria continue to act as strong deterrents for many Iranians to actively join protests.11James M. Lindsay, ‘The President’s Inbox Podcast: Protests in Iran, With Suzanne Maloney,’ Council on Foreign Relations, 8 November 2023

Moreover, calls for strikes went largely unheeded by significant sectors, including bazaar merchants and oil workers, groups that were instrumental in toppling the Pahlavi regime in 1979. This was likely due to several factors beyond regime intimidation, including recent pay rises the government provided to the public sector,12Christopher de Bellaigue, ‘Iran’s moment of truth: what will it take for the people to topple the regime?,’ The Guardian, 6 December 2022 as well as the dire state of the economy that has made it very difficult for merchants and shop owners to go on strike. Hard economic conditions also likely prevented segments of the working class, who were at the forefront of the previous two rounds of demonstrations, to join a prolonged period of demonstrations in pursuit of civil rights. But a further deterioration of Iran’s economic situation — already in dire condition after decades of mismanagement, corruption, and sanctions — could lead to a convergence of political and economic discontent and more intense outbreaks of unrest.

The recent wave of demonstrations that started after Amini’s death also illustrated that younger generations are increasingly ready to openly oppose the regime. Despite the high risk of repression, and the lack of arms among a majority of demonstrators, many participants in the protests were willing to directly resist the security forces. With the government significantly curbing the morality police’s activities,13Michael Lipin and Behrooz Samadbeygi, ‘Iran Curbs ‘Morality Police’ Amid Protests, Uses Other Oppressive Tools,’ Voice of America, 24 December 2022 and women increasingly appearing in public without their headscarves, a generation of teenagers has now experienced the transformational impact of collective action. As the Iranian government has largely extinguished the hope for meaningful reform, demonstrations have moved from the peaceful calls of the Green Movement in 2009 to more violent agitation for fundamental change. The increase in firearm use against security forces in recent months, though still sporadic and in small numbers, is a warning sign of a continuing cycle of violence in the country, and may suggest the possibility of increased armed activity in the future.

Developments in regions with predominant ethnic and sectarian minorities, particularly the Kurdish, Baluchi, and Arab areas — where opposition groups have previously launched sporadic attacks against the government — should also be closely watched. The demonstrations have so far largely been an internal movement. In the case of a future escalation of unrest, though, armed opposition groups, including Kurdish armed groups based in northern Iraq, may decide to renew their attacks on Iranian military and government targets. Yet, armed resistance in one border area is unlikely to prompt a domino effect nationally;14Farzin Nadimi and Patrick Clawson, ‘Violence in Iran’s Uprising: What Happens If Either Side Escalates?,’ The Washington Institute, 8 December 2022 a movement seen as a separatist bid for territory would likely be marginalized and lack broader public support. Moreover, the powerful IRGC will maintain its kinetic advantages, such as heavy armor and combat aircraft, and a guerrilla movement would be highly unlikely to significantly challenge the regime.15Tom O’Connor, ‘As Iran Unrest Turns to Armed Clashes, Government Prepares Fight to Survive,’ Newsweek, 1 December 2022 Nevertheless, having to confront internal unrest would force Tehran to turn inward and could weaken its position in the region.

Lastly, the conflation of internal unrest with the Iranian government’s support for Russia in its war against Ukraine has significantly tarnished Iran’s public image globally. Even European governments that traditionally supported diplomacy with the Islamic Republic have adopted harsher stances, making rapprochement between Iran and the West exceedingly difficult. Facing challenges on multiple fronts, it remains to be seen if the leadership in Iran will be willing to make any meaningful compromises. The authorities are showing signs of two minds — releasing several dozen well-known prisoners in an apparent attempt to appease the public while still carrying out death sentences, and curbing the activities of the morality police while at the same time enforcing the dress code through other means, including shutting down businesses.16Iran International, ‘Islamic Republic Trying New Measures To Enforce Hijab,’ 1 January 2023 Yet, the gulf between what the ruling elite can, or is willing, to provide and the population’s demands may have become so unbridgeable that instability is likely to grow.