Special Issue: Violence Targeting Local Officials

Mexico

Published: 22 June 2023

Violent Local-Level Political Dynamics

On 5 October, armed men stormed the municipal building of San Miguel Totolapan, a town that lies in the western Tierra Caliente region. Gunmen killed a total of 20 people, including Mayor Conrado Mendoza, his father who was also the former mayor of the town, and several law enforcement officers.1Nathan Williams, ‘Mexico mayor assassinated in town hall massacre,’ BBC News, 6 October 2022 While the public was struck by the lethality of the attack, it was far from an isolated case, as hundreds of elected representatives and civil servants are targeted each year in Mexico. Violence targeting local public officials has been particularly widespread across the country, with those serving in state and municipal bodies representing the vast majority of victims.

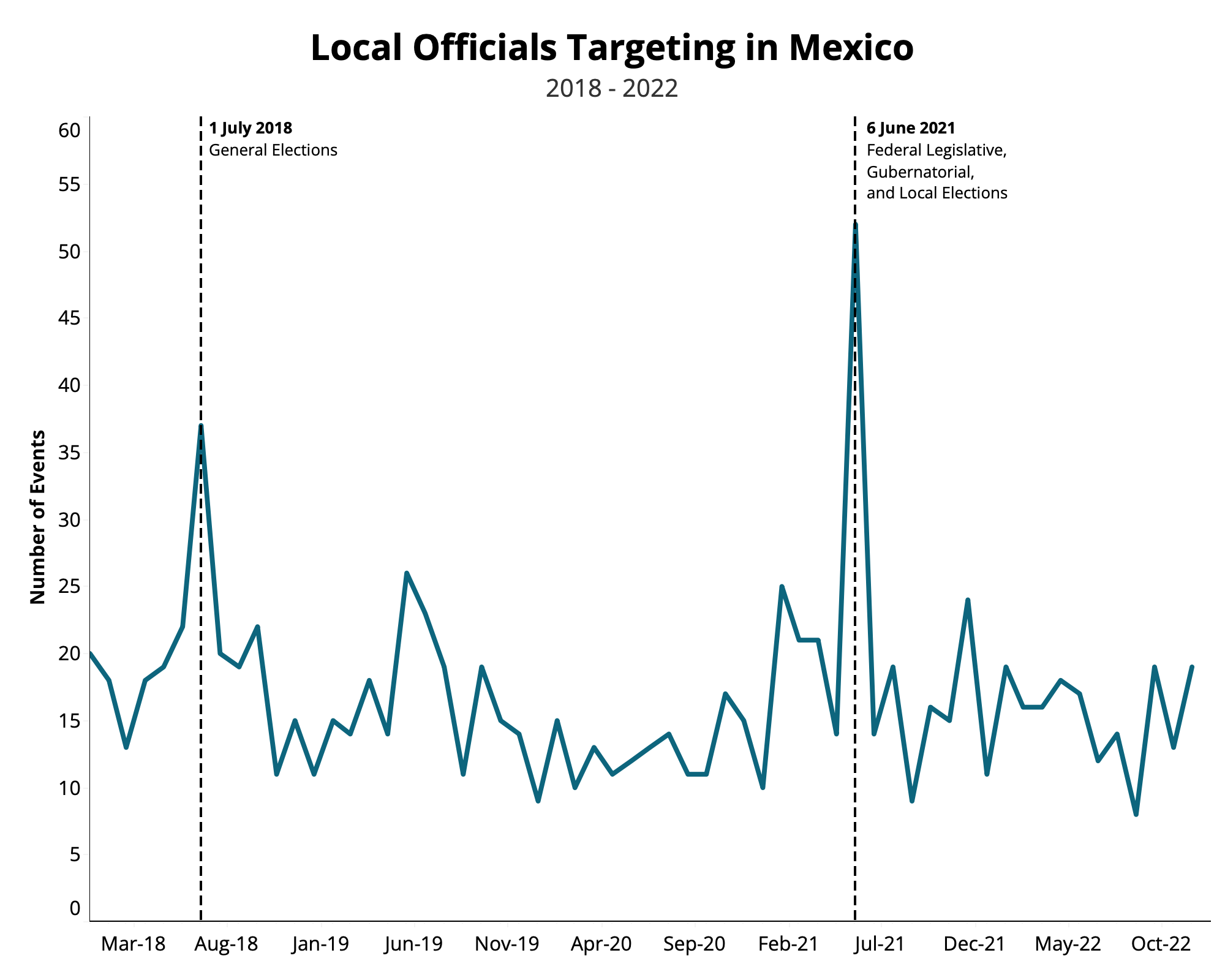

Authorities attributed the attack in San Miguel Totolapan to Los Tequileros, a criminal group that competes against La Familia Michoacana for the control of drug trafficking markets.2BBC, ‘Quiénes son los Tequileros, la banda criminal a la que se le atribuye la reciente masacre de 20 personas en México,’ 7 October 2022 Analysis of these attacks often singles out organized crime as the driving force behind violence targeting local officials. Electoral cycles are also understood to fuel spikes in such targeting, under the premise that organized crime groups threaten and assassinate public officials and candidates who could hamper their operations. ACLED records at least 20 events attributed to identified criminal groups and spikes in violence ahead of the 2018 general elections and 2021 elections of federal deputies, state governors, state congress, and municipal representatives.

This explanation accounts for some of the dynamics driving the targeting of local public officials. However, blaming organized crime alone fails to account for other actors and local power dynamics at play, as some observers have emphasized.3Gema Kloppe Santamaría, ‘Mexico’s recent election violence can’t be blamed on organized crime gangs alone,’ openDemocracy, 10 June 2021 This report seeks to challenge the monolithic interpretation of the targeting of local officials in Mexico. It highlights that violence targeting local public officials does not always coincide with hotspots of organized crime violence and areas where ACLED has recorded high levels of events likely related to gang violence. Other drivers contribute to this violence, including local disputes, elite competition, and weak protection mechanisms for local public officials.

Targeted Violence Beyond Organized Crime Hotspots

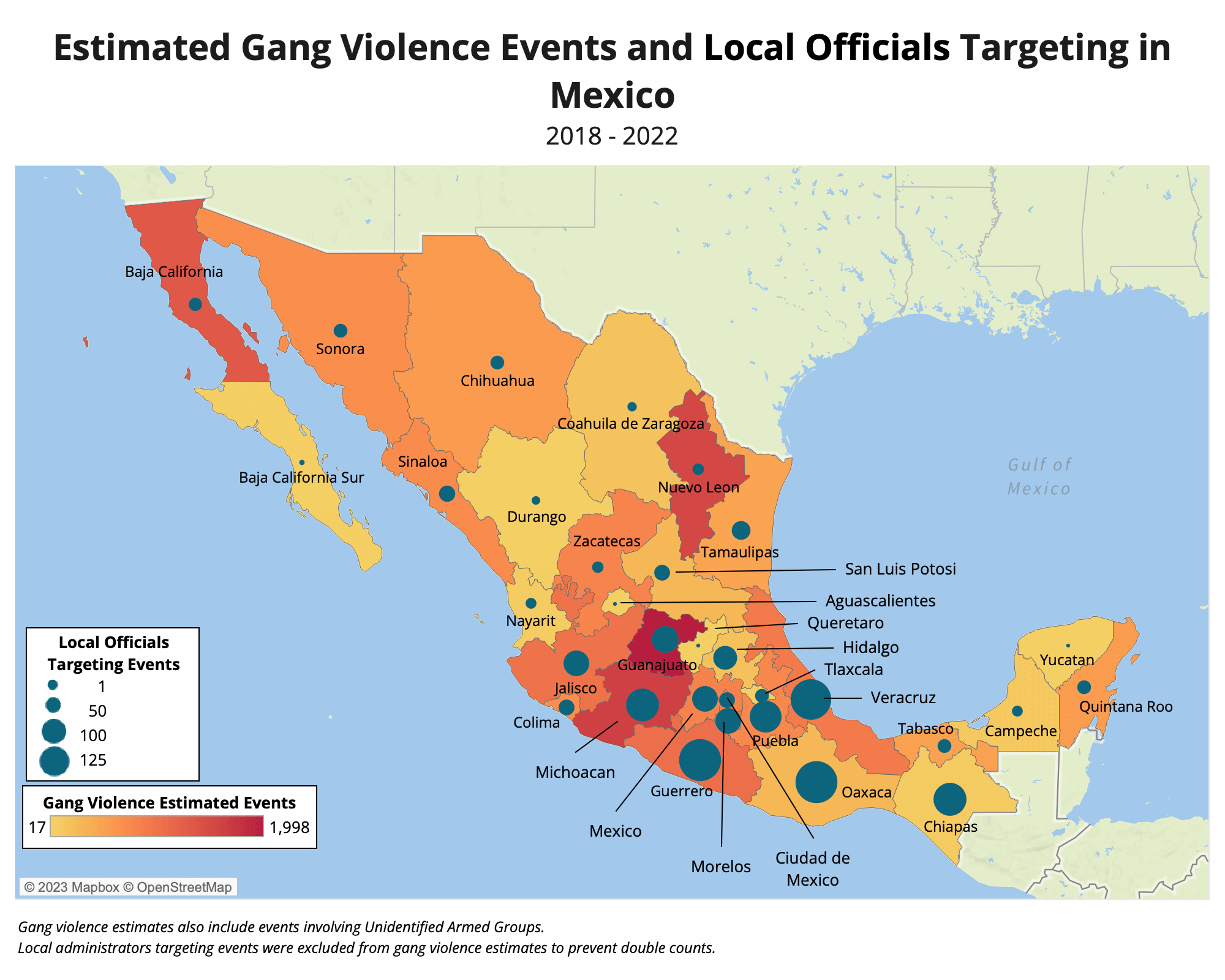

ACLED records violence targeting local officials across the country, with events in all 32 Mexican states. However, the distribution of the violence is not uniform, with violence clustering largely in the South Southeast and Central Western states (see map below). In some states, such as Michoacán, Guanajuato, Guerrero, and Veracruz, there is a correlation between violent actions against local officials and those likely connected to criminal gangs.4ACLED records violence likely related to gang activity when it involves the participation of two or more people and the use of specific techniques, tactics, and procedures such as – such as drive-by shootings, dismembering and execution-style killings. For more on how ACLED codes criminal violence, see ACLED Gang Violence: Concepts, Benchmarks and Coding Rules. However, this correlation does not hold true across the country. Indeed, Oaxaca and Chiapas states, where ACLED records some of the highest levels of violence targeting administrators, have relatively lower levels of events likely related to gang violence.

In Oaxaca state, ACLED records over 100 events of violence targeting local officials between 2018 and 2022, but the state does not feature among the most violent when looking at political violence events likely related to gang activity. Rather than gang-related, violence in this state can be partly attributed to political disputes. Some municipalities in this state are governed by uso y costumbres (uses and customs), a participatory electoral system overseeing the election of municipal authorities by a community assembly.5Etellekt, ‘Primer informe de violencia política en México, proceso electoral 2022,’ 1 June 2022 In these municipalities, the authoritarian rule of caciques, or local political bosses, and their interference in Indigenous organizations to win elections has led to divisions within these communities, and is likely a driver of violence against local officials.6Natividad Gutiérrez Chong, ‘Violencias en Oaxaca: pueblos indígenas, conflictos post electorales y violencia obstétrica,’ Senado de la República, Instituto Belisario Domínguez, 2017, p.317 The absence of clear rules and institutions to mediate conflicts has also prevented the adoption of long-term solutions for post-electoral disputes. Chiapas state has been the scene of similar tensions, notably in the community of Oxchuc, where in 2021, voting by uso y costumbres was suspended due to clashes between supporters of opposing groups.7Abraham Jiménez, ‘Suspenden elección de usos y costumbres en Oxchuc, Chiapas, por violencia,’ Milenio, 15 December 2021

Conversely, in Nuevo Leon and Baja California states, where gang disputes are rife, actions targeting local public officials have remained relatively low. The cause of the low levels of such targeted violence in these states is unclear. Rather than perpetrating direct violence, criminal groups are reported to make use of intimidations and threats with the aim of penetrating local authorities and influencing decision-making.8Infobae, ‘Narcopacto en Baja California: las claves de la acusación de Jaime Bonilla con el CJNG,’ 18 August 2022; Infobae, ‘“Vamos con todo”: la amenaza del CJNG a edil de San Pedro Garza,’ 13 May 2021

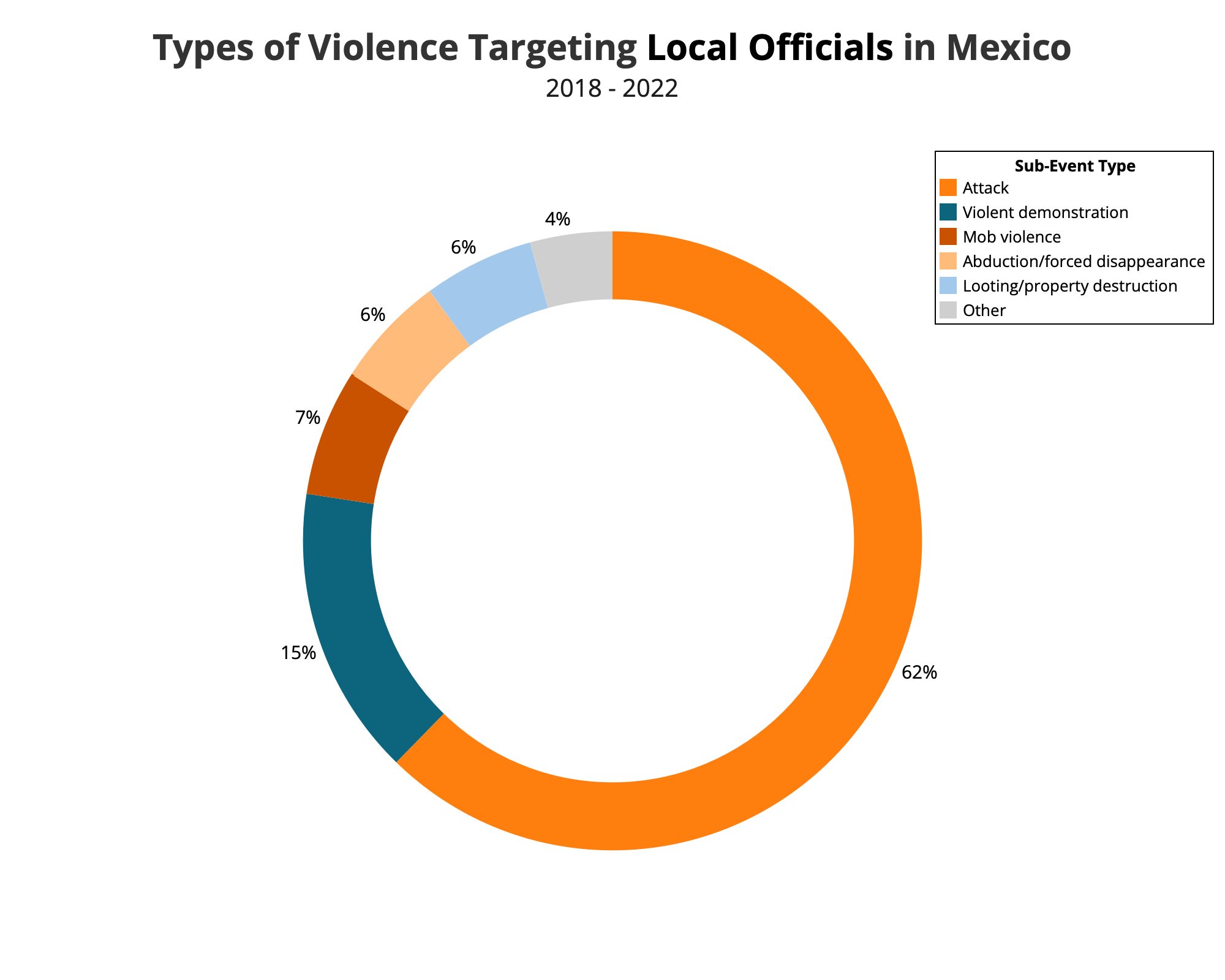

How Local Officials Are Threatened

Between 2018 and 2022, ACLED records about 1,000 events of violence targeting local officials. Direct attacks constitute a large majority of the violence recorded by ACLED, accounting for about 62% (see graph below). These actions typically involve several perpetrators or the use of specific techniques, tactics, and procedures – such as drive-by shootings and execution-style killings – that are often attributed to organized crime groups. While these manifestations of violence targeting local officials prevail, victims have faced a multiplicity of threats, including violence perpetrated by demonstrators and violent mobs, as well as non-direct physical intimidation targeting their properties.

Since 2018, violence in the context of riot events, including violent demonstrations and mob violence, represents the second largest share of physical threats faced by local officials. While the level of riot activity remains relatively constant over the years, it notably increases ahead of elections. This trend is especially apparent in June 2021, amid unrest at polling stations, electoral fraud claims, and ballot theft. Outside of election periods, rioters have temporarily detained and assaulted local officials for failing to address their demands. The vast majority of recorded riot events take place outside of state capitals and have mainly targeted representatives and employees of municipal authorities, which embody the political institution closest to the population.

Nonetheless, threats and intimidation can also be indicators of upcoming violence. Actions like the targeting of private or public property, which account for 6% of all recorded violent events between 2018 and 2022, rarely result in the injuring or killing of the targeted individual and, rather, suggest perpetrators intend it as a means of intimidation. Current and former local administrators who have reported threats have been subsequently assassinated, thus highlighting the limitations of the reporting and protection mechanisms.9Infobae, ‘Ejecutaron a David Sánchez, ex alcalde de Apaseo el Alto, Guanajuato,’ 16 June 2021 Recently, on 1 May 2023, gunmen killed the former mayor of Tonaya, Jalisco in Baja California state, where he had moved after receiving threats presumed to be from an organized criminal group.10Ernesto Gómez, ‘Asesinan a ex alcalde de Tonaya cerca del aeropuerto de Tijuana,’ Informador.mx, 2 May 2023 ACLED also records over 30 instances of violence that resulted in clashes with security bodies escorting local officials, further suggesting the victims’ vulnerability despite protective measures. Protection mechanisms are centralized within federal agencies, which has raised questions about their efficiency and accessibility at the local level, as they are hindered by a lack of trust and collaboration between federal and local authorities.11Ana Velasco Ugalde, ‘Policy Report n°2 – Protection Protocols for Electoral Candidates in Mexico,’ Noria Research, 1 June 2021

Moreover, the threats faced by political actors are likely under-reported, despite several initiatives systematizing reports of intimidation. Thus, the violence and psychological pressure exerted on local government officials could be even more significant than what is already quantifiable.12Rubén Salazar Vázquez, ‘Cuarto Informe de Violencia Política en México 2021,’ Etellekt, 5 May 2021

Elections Exacerbate Threats to Local Officials

ACLED data indicate that levels of violence targeting local officials typically fluctuate according to electoral cycles. Some of the highest levels of violence are recorded in 2018 during Mexico’s general elections and 2021 during the elections of federal deputies, state governors, state congress, and municipal representatives (see graph below). In 2018 and 2021, notably, ACLED records at least 10 and 20 violent incidents targeting candidates who were also serving as local administrators, respectively.

The perpetrators’ motives remain unknown in the majority of cases amid a high rate of impunity. Despite this lack of official accountability, the violence is often labeled as the work of organized crime groups.13Elena Reina, ‘La impunidad crece en México: un 94,8% de los casos no se resuelven,’ El País, 5 October 2021; Gema Kloppe Santamaria, ‘Mexico’s recent election violence can’t be blamed on organized crime gangs alone,’ Open Democracy, 10 June 2021 The narrative that is assigned is often one where organized crime groups use violence to influence election outcomes and advantage affiliated candidates, in return for guarantees that law enforcement and rival criminal groups will not interfere in their activities.14Yuri Neves, ‘What’s Behind the Killings of Mexico’s Mayors,’ InSight Crime, 28 May 2019; Guillermo Trejo and Sandra Ley, ‘High-Profile Criminal Violence: Why Drug Cartels Murder Government Officials and Party Candidates in Mexico,’ British Journal of Political Science, 2021, p.206 The prevalence of specific techniques, tactics, and procedures typically associated with organized crime groups has notably driven this interpretation. However, this has been criticized for failing to track the masterminds behind the violence.15María Teresa Martínez Trujillo and Sebastián Fajardo Turner, ‘Policy Report n°1 – Data Analysis on Electoral and Political Violence 2020-2021,’ Noria Research, 1 June 2021

Rivalries and disputes between political elites also serve as an important driver of violence targeting local officials. Notably, candidates have increasingly relied on organized crime to secure funding for campaigning, votes, and security guarantees in areas where criminal competition has led to high levels of violence.16International Crisis Group, ‘Electoral Violence and Illicit Influence in Mexico’s Hot Land,’ 2 June 2021; Romain Le Cour-Grandmaison, ‘Ten years of vigilantes. The Mexican autodefensas,’ Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, 7 March 2023 Although rarely prosecuted and identified, some politicians are believed to use the services of non-partisan enforcers to threaten or attack their opponents.17Andreas Schedler, ‘Making Sense of Electoral Violence: The Narrative Frame of Organised Crime in Mexico,’ Journal of Latin American Studies, 2022, p.492 On 4 June 2021, the campaign manager for mayoral candidate René Tovar in Cazones de Herrera municipality, Veracruz ordered an attack on Tovar to substitute him in the position.18El Siglo de Torreón, ‘Alcalde electo en Veracruz es detenido por asesinato de candidato de Movimiento Ciudadano,’ 23 June 2021 Similarly, a Citizens’ Movement candidate in the municipal elections of Cocula, Guerrero reported that he had received threats from his opponent from the Morena party.19Sergio Ocampo Arista, ‘Candidato de MC en Cocula, Guerrero, tiene custodia, tras amenazas,’ La Jornada, 5 May 2021

Criminal, political, and private actors’ stakes in local election results have led to high levels of violence both in the lead-up to the elections and during voting. On 1 July 2018, the day of Mexico’s general elections, ACLED records a spike in events, stemming from the targeting of local electoral staff and polling stations, and the theft and destruction of ballot boxes, including at least six such reported events in Puebla state. Similarly, in 2021, the highest number of violent events targeting local officials occurred on voting day on 6 June, with armed men and mobs targeting polling stations, especially in Jalisco and Oaxaca states. The drivers of violence in these states are not uniform, but rather answer to local dynamics of power. Previous records of electoral conflicts on voting day, however, have allowed the National Electoral Institute (INE) – an autonomous body overseeing the organization and regulations of elections – to identify municipalities at risk of violence ahead of the general elections scheduled for 2024.20Ilse Aguilar, ‘INE pone la lupa en municipios con violencia, ante elecciones de 2024,’ Publimetro, 21 May 2023

Yet, local officials are the target of violent actors beyond the main electoral periods. Despite a relative decrease compared to 2018 and 2021, a high number of violent events was also reported in 2019 and 2022, a testament to persisting criminal and political rivalries that materialize during administration shifts at the regional and local levels. Criminal groups have notably targeted local administrators beyond elections, exacting retaliation against officials who fail to deliver on pre-electoral agreements and prevent security operations against their activities.21International Crisis Group, ‘Electoral Violence and Illicit Influence in Mexico’s Hot Land,’ 2 June 2021 Organized crime groups have also frequently targeted local officials due to their collaboration with rival groups.22Justice in Mexico, ‘Mexico’s 2021 Elections Rocked By Political Violence,’ 29 June 2021 In August 2022, members of Jalisco New Generation Cartel attacked a worker serving at Irapuato municipality in Guanajuato state for his alleged ties with the rival Santa Rosa de Lima Cartel.23La Opinión, ‘El CJNG habría matado a los luchadores “Maremoto” y “Lepra Mx” en Guanajuato,’ 30 August 2022 Likewise, the attack launched by Los Tequileros in San Miguel Totolapan in Guerrero, came before the mayor was allegedly scheduled to meet with the head of La Familia Michoacana, a rival criminal group operating in the same region.24BBC, ‘Quiénes son los Tequileros, la banda criminal a la que se le atribuye la reciente masacre de 20 personas en México,’ 7 October 2022

Political rivalries and interpersonal conflicts are also reported to contribute to violence beyond electoral cycles. For instance, on 14 February 2023, the sons of a former mayor of Santiago Amoltepec, Oaxaca state, and their bodyguards clashed with municipal police forces while allegedly attempting to kill the incumbent mayor. This example particularly highlights that local officials may be involved – as either instigators or victims – in violent actions while no longer in office. Since 2018, ACLED records the killing of over 200 former elected officials in regional and local offices across the country.

Prospects Ahead of the 2024 General Elections

In outlining the multitude of threats faced by local public officials, this report challenges common understandings of political violence in Mexico as a function of organized crime alone, and draws instead attention to the political disputes and power dynamics that contribute to widespread violence. So far, 2023 paints a worrying picture of violence targeting local officials in Mexico. Between January and May 2023, ACLED records over 100 reported violent events, marking a 32% increase compared to levels recorded during the same period in 2022. However, even as local elections were held on 4 June in Coahuila and Mexico states, many violent incidents took place in Oaxaca, Morelos, Guerrero, Michoacán, Veracruz, and Puebla states. In these states, ACLED has consistently recorded high levels of violence targeting local officials amid organized crime group activity and political conflicts.

The next general elections scheduled for June 2024 are likely to exacerbate tensions and heighten the risks of violence. Local officials and candidates are especially at risk, and competition to secure an electoral seat might further compound these threats. The adoption of reforms to the INE could set fertile grounds for unrest and electoral conflicts around voting outcomes. The reform, adopted in February 2023, sets provisions for budget and staff cuts that are expected to reduce its monitoring and arbitration capacity.25Vanessa Buschschlüter, ‘Mexico passes controversial reform of election watchdog,’ BBC, 23 February 2023 President Andrés Manuel López Obrador has pushed for the reform and openly criticized the institution, accusing it of partiality and failing to address previous electoral fraud claims in elections in which he participated.26Valerie Wirtschafter and Arturo Sarukhan, ‘Mexico takes another step toward its authoritarian past,’ The Brookings Institution, 16 March 2023 These criticisms are likely to further delegitimize the INE as an institutional recourse in the event of an electoral conflict.

Visuals in this report were produced by Ciro Murillo