Special Issue: Violence Targeting Local Officials

The Philippines

Published: 22 June 2023

Rivalries Between Local Elites Fuel Violence

The Philippines has historically grappled with a high level of violence targeting local administration officials, particularly in relation to electoral competition between local elite families. The high-profile assassination of Negros Oriental Governor Roel Degamo in March 2023 is a recent example that illustrates this phenomenon.1Rappler, ‘Negros Oriental Governor Roel Degamo killed in attack,’ 4 March 2023 However, such violence has long persisted in the Philippine countryside. The most notorious example is the Maguindanao Massacre of November 2009, in which 58 people were killed in an attack masterminded by members of the Ampatuan clan against their rival Mangudadatu family.2Lian Buan, ‘Ampatuan brothers convicted in 10-year massacre case,’ Rappler, 19 December 2019 The attack is also thought to be the most lethal assault on the press in contemporary history, as 32 journalists were among those killed.3Jamie Wiseman, ‘Verdict looms 10 years after Philippine press massacre,’ International Press Institute, 14 July 2019; Al Jazeera, ‘Timeline: The Maguindanao killings and the struggle for justice,’ 19 December 2019 The massacre took the lives of several members of the Mangudadatu family during an election-related event, including a vice mayor and other relatives of a Mangudadatu scion set to run against an Ampatuan for governor.4Ben Rosario, ‘Mangudadatu recalls Maguindanao massacre,’ Manila Bulletin, 22 November 2019

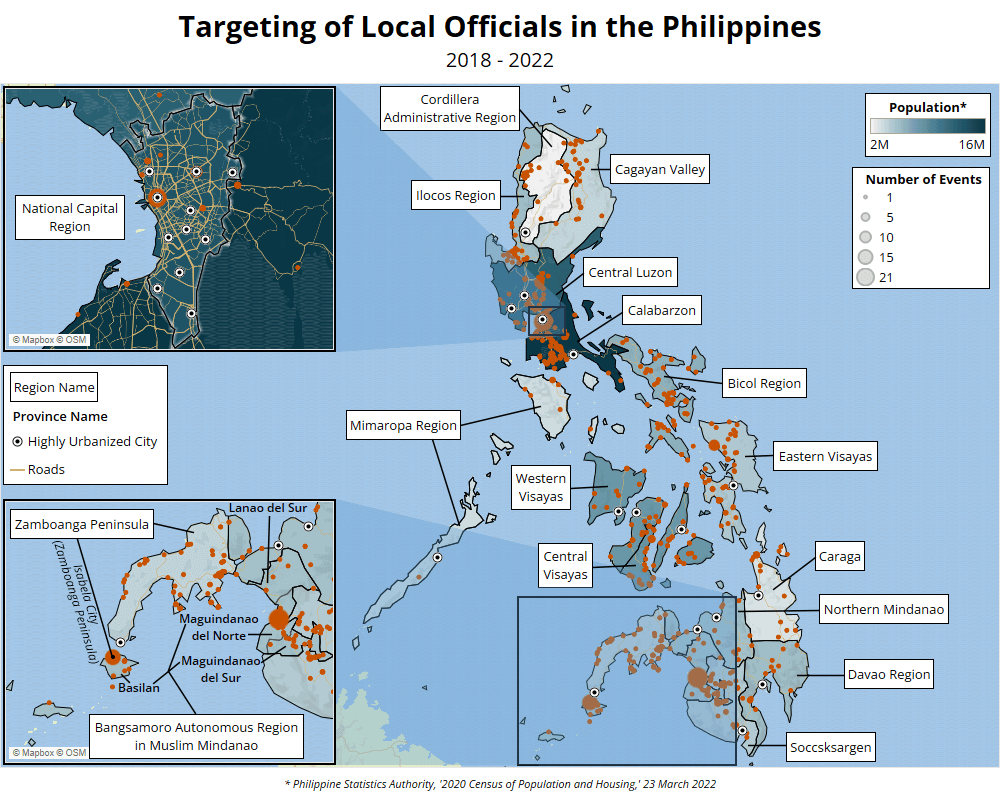

These examples reflect the brazen nature of such violence. However, its prevalence is equally alarming: ACLED records 716 acts of violence against local officials between 2018 and 2022. Such violence is heavily concentrated in rural areas, particularly in the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (BARMM), and especially during election periods. ACLED data show notable spikes of violent events targeting local government officials during the May 2019 midterm and May 2022 general elections, with BARMM, particularly the Maguindanao provinces, accounting for a disproportionately high amount of such targeting.

BARMM, like other rural areas that see elevated levels of such violence, is marked by conflict and characterized by a devolved political system, the proliferation of political dynasties, and the domination of ‘strong families’ who find recourse in violence to secure their interests. This report examines the temporal and subnational patterns seen in the targeting of local officials in the Philippines.

Electoral Violence Driven by Hired Unidentified Assailants

While the Philippines is home to many conflicts, including the communist insurgency as well as the Moro separatist struggle in Mindanao, a large percentage of the violence targeting local officials occurs outside of such conflicts. Many attacks occur without clear motives identified in media reports. ACLED data show 79% of violence targeting local government members between 2018 and 2022 was committed by unidentified actors. While the identity of those who carry out such violence is often unknown, much of this violence is thought to be committed by hired killers acting at the behest of local political players, and also possibly by members of private armed groups associated with political families.5Vincent Kyle Parada, ‘Politics, power and private armed groups in the Philippines,’ East Asia Forum, 14 April 2023 Peace Research Institute Frankfurt Professor Peter Kreuzer found that political players are more likely to engage hired guns for one-off or rare operations, rather than utilizing a private army that might be better known to law enforcement and thus easier to connect to the mastermind. As such, Kreuzer notes that “in the vast majority of cases it cannot be proven who actually ordered the killings.”6Peter Kreuzer, ‘Killing Politicians in the Philippines: Who, Where, When, and Why,’ Peace Research Institute Frankfurt, 2022

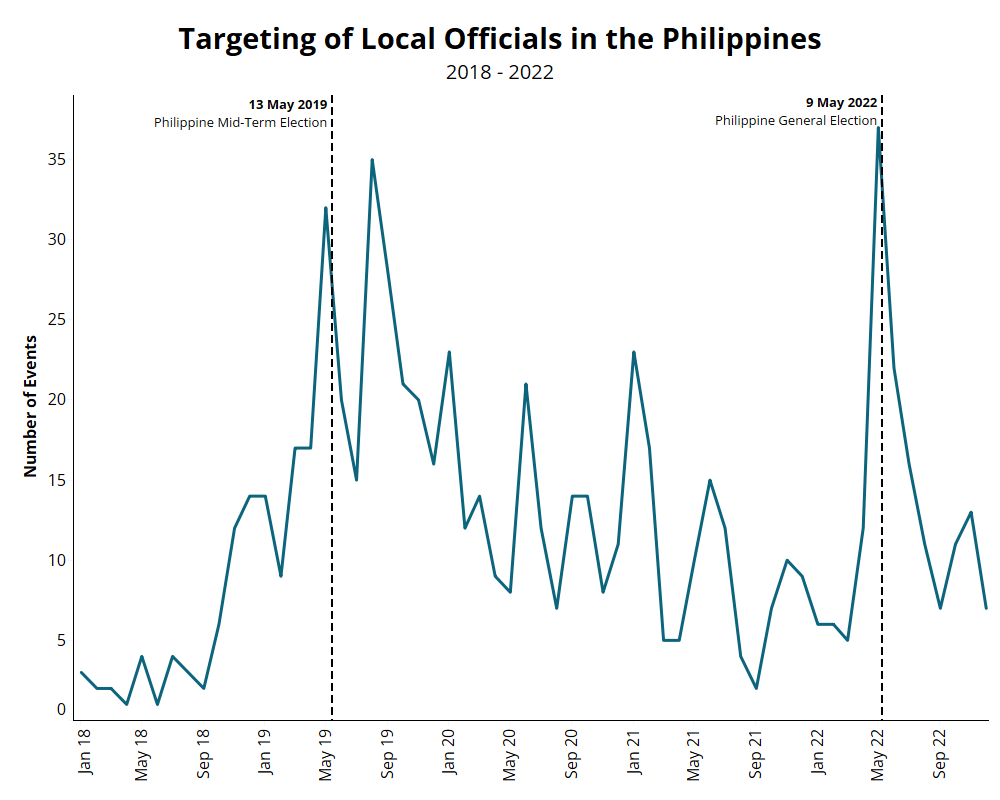

Political competition drives spikes in the targeting of local officials in the Philippines, as evidenced by increases in such violence during election seasons.7Imelda Deinla et al., ‘Introducing the Philippine Electoral Violence (PEV) data set: Uncovering trends, targets, and perpetrators of election-related violence during the 2013–2019 elections,’ Asian Politics & Policy, 12 April 2023 ACLED data show a significant increase in the targeting of local officials around midterm elections in May 2019 and around presidential elections in May 2022 that saw the transition from President Rodrigo Duterte to new President Ferdinand ‘Bongbong’ Marcos, Jr. (see figure below). Over 30 such violent events were seen in May 2019, followed by an even higher peak of nearly 35 events in August 2019, fresh into the election winners’ new terms. The May 2022 election period was even more violent, with over 35 violent events targeting local officials during that election month alone.

This electoral violence is partly driven by electoral competition between political dynasties. The Philippine political landscape is characterized by the proliferation of political dynasties, as well as the system of political patronage they depend on for survival. Political dynasties, or the capture of multiple or successive elective posts by members of the same family, are technically banned by the Philippine 1987 Constitution. However, this ban has not been operationalized due to the lack of a required enabling law8Andrew J. Masigan, ‘Evils of political dynasties,’ BusinessWorld, 11 November 2018; Frances Mangosing, ‘Carpio: Lack of law enabling Charter’s dynasty ban allows Sara to replace father,’ INQUIRER.net, 15 July 2021 – one that has a poor chance of passing in a House of Representatives dominated by political dynasties.9Neil Arwin Mercado, ‘House ‘unlikely’ to pass Anti-Political Dynasty bill — solon,’ INQUIRER.net, 22 July 2020 As of 2016, 78% of the members of the House of Representatives were part of political dynasties.10Philip C. Tubeza, ‘Study says ‘fat’ dynasties behind worsening poverty,’ INQUIRER.net, 16 February 2018

The 2019 attack on Amado Espino, Jr., a former governor and representative of Pangasinan province in the Ilocos Region, is a typical example of such violence involving political dynasties. Espino is the patriarch of a powerful clan that has seen several members in top elected positions, such as his son who was then the incumbent governor. In an ambush on 11 September 2019, assailants injured Espino and killed a police officer serving as Espino’s aide. Hired assailants, including a former scout ranger from the Philippine Army, perpetrated the ambush.11Rambo Talabong, ‘Former Pangasinan governor Amado Espino Jr ambushed,’ Rappler, 11 September 2019; Yolanda Sotelo, ‘Family of ex-Pangasinan gov Espino Jr. condemns ambush,’ INQUIRER.net, 12 September 2019; Yolanda Sotelo, ‘22 suspects face murder, frustrated murder raps for Espino ambush,’ INQUIRER.net, 2 October 2019; Liezle Basa Iñigo, ‘Ex-Scout Ranger tagged in ambush of former Pangasinan Gov. Espino in 2019 nabbed,’ Manila Bulletin, 24 June 2022

Police investigators later identified the attack’s mastermind as Raul Sison, a provincial board member from a smaller political dynasty whose son was also serving as a town mayor. The alleged mastermind died due to COVID-19 in March 2020 and the motive for the attack is still unclear.12GMA News, ‘Pangasinan board member tagged as mastermind in ambush of ex-Gov Espino, 13 February 2021; Emmanuel Tupas, ‘Espino ambush: Ex-Pangasinan board member tagged as brains,’ Philippine Star, 14 February 2021; Eva Visperas, ‘“My father died on March 26, 2020” – Mayor Sison,’ Sunday Punch, 22 February 2021 Nonetheless, Sison was described in a media report as a ‘deserter’ of the Espino camp, which was engaged in fierce electoral battles.13Ahikam Pasion and Inday Espina-Varona, ‘Political Dynasties 2022: Espinos still lynchpin of Pangasinan politics,’ Rappler, 30 April 2022 Espino again ran for governor in 2022, though he lost in an upset.14Ahikam Pasion, ‘Espino brothers lose in Pangasinan gubernatorial, congressional races,’ Rappler, 12 May 2022

These dynamics in local politics have led some observers of Philippine society to note the outsized impact of ‘strong families,’ representing a dominant oligarchic class who thrive on political patronage vis-à-vis the ineffectual presence of the so-called ‘weak state’ in their localities.15Alfred W. McCoy, ‘An Anarchy of Families: State and Family in the Philippines,’ University of Wisconsin Press, 2009 Such a reality, coupled with the weakness of political parties in the Philippines, also means families play an outsized role in the political landscape, taking on the role played by parties in other contexts as vectors for political movement.16Paul D. Hutchcroft, ‘Strong Patronage, Weak Parties: The Case for Electoral System Redesign in the Philippines,’ World Scientific, 2020; Julio Teehankee, ‘Electoral politics in the Philippines,’ Electoral Politics in Southeast and East Asia, 2002, p.149-202 When multiple oligarchic families find themselves competing for the same set of elective posts, all promising access to lucrative local budgets and discretionary funds, some end up finding recourse in political violence to secure desired political outcomes. This phenomenon was referred to by Kreuzer as ‘violent self-help,’ which appears to have been accepted as a political reality in certain settings in the Philippines.17Peter Kreuzer, ‘Violence as a Means of Control and Domination in the Southern Philippines,’ Peace Research Institute Frankfurt, 2011 The prevalence of violent self-help among political families collapses the lines separating the institutional and personal, whereby extra-institutional means are used to secure the dynasty’s hold on power.

Further, recent research into the impact of political dynasties on Philippine society shows that political violence is a manifestation of both political and socioeconomic inequality. In areas outside the capital Manila and the main island of Luzon, which enjoy greater distance from close institutional surveillance, the persistence of political dynasties is associated with greater poverty.18Ronald U. Mendoza et al., ‘Political dynasties and poverty: measurement and evidence of linkages in the Philippines,’ Oxford Development Studies, 11 April 2016, pp. 189-201 Such areas are commonly dominated by local ‘bosses’ who seize control over an area’s resources, partly through coercion and partly through institutional legal means.19John T. Sidel, ‘Capital, Coercion, and Crime: Bossism in the Philippines,’ Stanford University Press, 1999

The poverty in these areas has helped generate a prevalence of actors willing to take up political violence. However, it is not just dejected, impoverished citizens who turn toward violence as an appealing alternative to their current reality. Rather, segments of the elite, usually dynastic political families, try to secure their interests by actively turning toward such actors to do their bidding.20Ronald U. Mendoza et al., ‘Political Dynasties and Terrorism: An Empirical Analysis Using Data on the Philippines,’ Asian Journal of Peacebuilding, 2022, pp. 435-459 The concentration of political violence in areas far removed from national centers of power is, thus, a sign of the weakness of institutions and inadequately established government accountability.

Local Officials in BARMM at Higher Risk

The targeting of local officials in the Philippines is concentrated mostly in rural areas. ACLED data show that between 2018 and 2022, just under 86% of events tagged in the ACLED data set as violence targeting local officials occurred in rural areas. For the purposes of this report, rural areas are defined as all areas in the Philippines outside of 33 cities described as “highly urbanized” in the 2020 census, which include 16 cities in the National Capital Region (NCR) and 17 cities outside the NCR.21Philippine Statistics Authority, ‘Highlights of the Philippine Population 2020 Census of Population and Housing (2020 CPH),’ 13 July 2021

The prevalence of this phenomenon in the Philippines, particularly in rural areas, is rooted in certain rural dynamics that facilitate an easy recourse to political violence. One relevant characteristic of the rural Philippines is the power and influence of local politicians in charge of and competing for positions in the local government unit. Such power and influence derive largely from a decades-long governmental push toward devolution. This process was definitively ignited by the enactment of the Local Government Code of 1991, which delegated most basic governmental functions and services to the different levels of local government.22Alex B. Brillantes Jr, ‘Federalism, decentralization and devolution: A continuing debate in the Philippines,’ ABS-CBN, 13 June 2019

Violence is often seen in the very lowest levels of Philippine governance. ACLED data show that a significant portion of violence targeting local authorities is committed against officials in barangays (sub-city or sub-town districts), such as barangay chairpersons and barangay councilors. A smaller number of attacks concern other local administrative positions – from the municipal or city levels, all the way to the provincial level.

The geographical patterns of violence against local officials largely track with the general population of the country. As such, the eight regions comprising the country’s largest island group of Luzon – home to nearly 60% of the country’s population – make up the largest share of violent events against local officials between 2018 and 2022. Mindanao and the Visayas followed. However, some regions have a disproportionately higher share of such violence relative to their population, particularly the BARMM. While BARMM falls in the middle of the pack in terms of its national population share, at 4%,23Philippine Statistics Authority, ‘Highlights of the Philippine Population 2020 Census of Population and Housing (2020 CPH),’ 13 July 2021 it sees the second highest number of violent events against local officials between 2018 and 2022 (see map below). Slightly over 10% of violence targeting local officials occurred in BARMM, trailing only slightly behind Calabarzon – the country’s most populous region – at nearly 11%.

Within BARMM, the two Maguindanao provinces comprised nearly three-fourths of all violent events targeting local officials between 2018 and 2022. Maguindanao del Norte saw 44% of such violent events in the region, while Maguindanao del Sur recorded 32%. Lanao del Sur and Basilan (excluding Isabela City, which is not part of BARMM as per the 2019 Bangsamoro plebiscite) also see elevated levels of violence.

The intersection of multiple issues characterizes the situation in BARMM. In particular, the Maguindanao provinces – a single province until a 2022 referendum – are beset by rivalries between dynastic families caught in rido, a term for clan feuds in BARMM.24Islamic Relief, ‘Combining traditional, formal and NGO peacebuilding to resolve violent Rido in Maguindanao,’ 1 September 2021; International Crisis Group, ‘Southern Philippines: Tackling Clan Politics in the Bangsamoro,’ 14 April 2020 These deeply rooted disputes extend from issues over land, to the contestation of political positions. In rido-related disputes, militias affiliated with rival clans sometimes engage in clashes, or carry out attacks against the rival clan, in some cases leading to the deaths of prominent rival clan members, including those working in local government. Such conflict occurs amid a difficult security landscape defined by the presence of armed groups, such as the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) and Islamic State-inspired breakaways, such as the Bangsamoro Islamic Freedom Fighters. A telling manifestation of this interplay between preexisting local conflict dynamics and violence targeting local officials is the fact that the masterminds behind the Maguindanao Massacre of 2009 initially tried to pass the blame on to the MILF.25Al Jazeera, ‘Timeline: The Maguindanao killings and the struggle for justice,’ 19 December 2019; ABS-CBN News, ‘MILF denies Ampatuan’s claims,’ 27 November 2009

Notably, data from the 2019 midterm elections show that the former single Maguindanao province also had the highest national rank in terms of the share of ‘fat dynasties,’ defined as families with two or more members in elected office. There, 51% of elected posts were occupied by members of fat dynasties.26Ronald U. Mendoza, Leonardo M. Jaminola, and Jurel Yap, ‘From Fat to Obese: Political Dynasties after the 2019 Midterm Elections,’ Ateneo School of Government Working Paper Series, September 2019 In this context, where actors from different conflicts often associate with powerful families and vice versa, and where ongoing issues have generated an abundance of firearms,27Ronald U. Mendoza et al., ‘Political Dynasties and Terrorism: An Empirical Analysis Using Data on the Philippines,’ Asian Journal of Peacebuilding, 2022, 435-459; International Crisis Group, ‘Southern Philippines: Tackling Clan Politics in the Bangsamoro,’ 14 April 2020; Francisco J. Lara, Jr., ‘Insurgents, Clans, and States: Political Legitimacy and Resurgent Conflict in Muslim Mindanao, Philippines, University of Hawai’i Press, October 2014 fighting can involve the killing of local officials who happen to be an obstacle to the interests of a local boss.

Violent Recourse for Elite Interests

Violence against local officials in the Philippines is a multifaceted issue, reflecting long-standing, historically rooted political and socioeconomic realities. Other ongoing issues of political violence in the Philippines also influence the way such realities play out, therefore comprising a complex web of political violence in the country. This political violence was recently again dramatically brought to the spotlight through the aforementioned killing of Negros Oriental Governor Degamo on 4 March 2023. The incident, which followed a high-profile electoral dispute, again illustrated some common aspects of such events: hired killers carrying out an operation after allegedly being contracted by members of a rival political family.

Degamo had faced off in the Negros Oriental gubernatorial race in May 2022 against a member of the powerful, dynastic Teves family, whose dominance in Negros Oriental resembles the Espinos’ position in Pangasinan. While Pryde Henry Teves was initially declared the winner in that May 2022 race, the Commission on Elections later nullified his win after ruling that thousands of additional votes were rightfully awarded to Degamo.28Jairo Bolledo, ‘Who is Roel Degamo, the slain Negros Oriental governor?,’ Rappler, 4 March 2023 Degamo thus took over as governor – though his time in office was cut short. The killing was carried out professionally by at least 16 ‘highly skilled’ and heavily armed assailants, including former dishonorably discharged soldiers and even a former New People’s Army rebel.29Sofia Tomacruz, ‘Degamo slay prompts Army to strengthen intel on former soldiers,’ Rappler, 9 March 2023; CNN Philippines, ‘Ex-NPA member identified as one of suspects in Degamo murder,’ 15 March 2023

The Degamo case is somewhat atypical in that the assailants and the mastermind were identified with relative speed. State prosecutors are considering Arnolfo Teves, Jr., the brother of Pryde Henry and a sitting member of Congress, the top mastermind in the killing.30Marc Jayson Cayabyab, ‘Teves considered ‘highest mastermind’ in Degamo slay,’ The Philippine Star, 4 April 2023 The Degamo killing thus demonstrates how some locally powerful elites continue to feel emboldened to engage in violent self-help. Such violence secures an elite’s continued political and economic interests – against not only those of a rival elite, but the public interest at large.