Special Issue: Violence Targeting Local Officials

European Union

Published: 22 June 2023

Unidentified Violent Assailants Target Local Officials

A policy study commissioned by the European Parliament in July 2020 found that growing polarization and social tensions within the European Union contribute to the direct exposure of local officials to hatred and violence.1European Parliament, ‘Hate speech and hate crime in the EU and the evaluation of online content regulation approaches,’ July 2020 This study linked the murder of Pawel Adamowicz2Daniel Tilles, ‘Polish mayor’s killer found guilty and given life sentence,’ Notes from Poland, 16 March 2023 – the mayor of the Polish city of Gdansk – and Walter Luebcke3RFI, ‘Verdict due in murder of German pro-migration politician’, 28 January 2021 – a Christian democratic politician and president of the German region of Kassel – to hate speech. More recently, the French mayor of Saint-Brevin-les-Pins resigned from his post lamenting a “lack of state support” after being exposed to far-right death threats and an arson attack over the opening of a government-backed refugee center in his town.4Hélène Roussel, ‘Menacé, attaqué, le maire de Saint-Brevin démissionne et quitte la ville,’ France Bleu, 10 May 2023; RFI, ‘French mayor’s resignation amid far-right death threats sparks outcry,’ 11 May 2023 Taken together, these events across the EU suggest that local officials find themselves in the ‘firing line’; violence against them is used as an expression of opposition and growing disenchantment with national policies, or to secure private or organized interests locally.5Benoît Floc’h, ‘’I wasn’t elected for this: French mayors in firing line as violence and death threats on the rise,’ Le Monde, 26 November 2022; Katrin Bennhold and Melissa Eddy, ‘’Politics of Hate’ Takes a Toll in Germany Well Beyond Immigrants,’ The New York Times, 21 February 2020; Gianmarco Daniele, ‘How the mafia uses violence to control politics,’ The Conversation, 26 September 2018

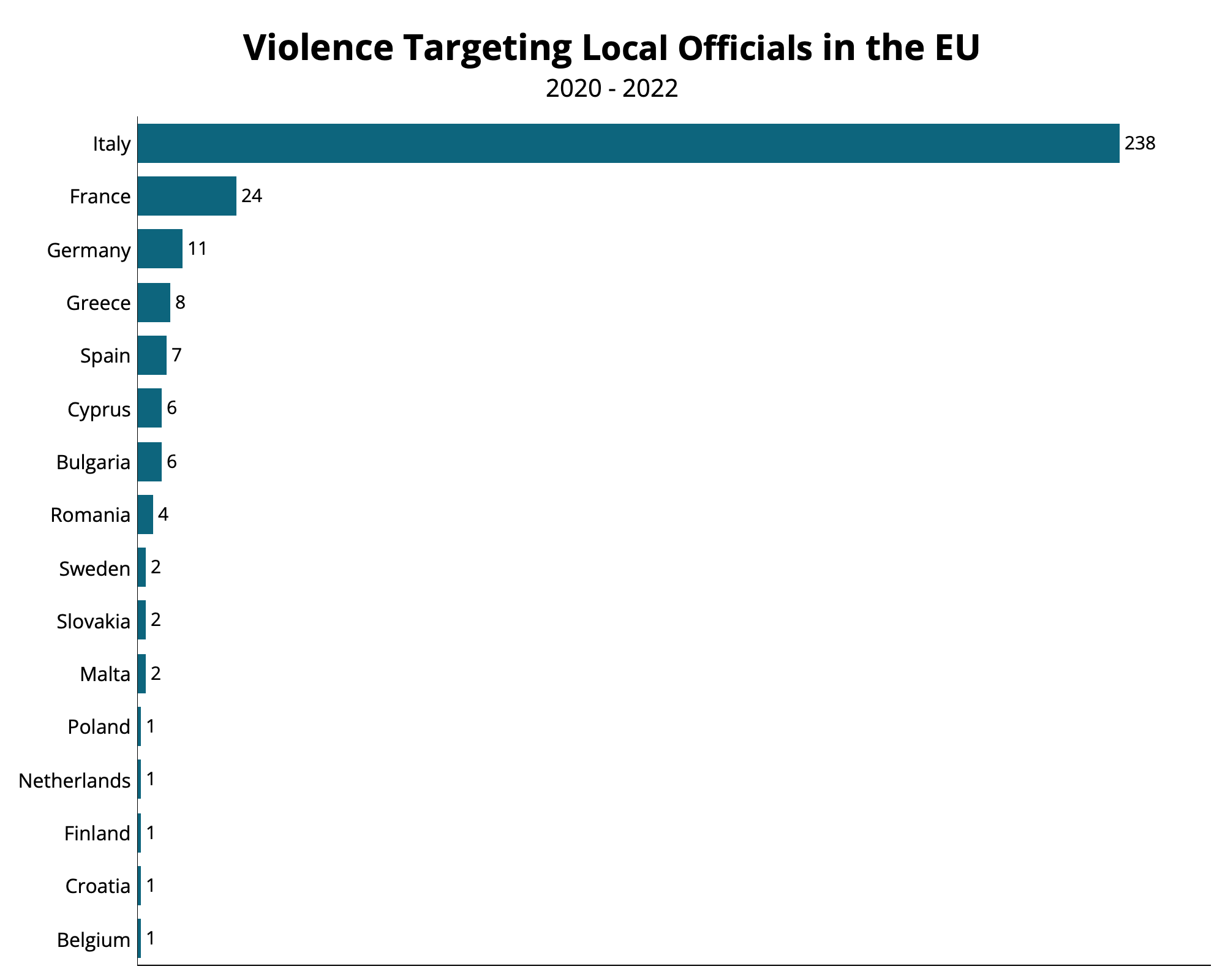

ACLED data between 2020 and 2022 shows that the perpetrators of this violence are overwhelmingly unidentified – approximately 85% of all recorded events targeting local officials in the EU during that period having been committed anonymously. This anonymity among assailants across the board suggests a complicated patchwork of risks faced by local authorities in the region, where physical violence and online and verbal threats against them are a widespread phenomenon, although varying in intensity. Between 2020 and 2022, ACLED records events in 16 out of 27 EU countries (see graph below). However, 75% of all events reported across the region were recorded in Italy, where local officials in the south of the country face the most risk.

This report explores the targeting of local officials between 2020 and 2022 across EU countries, with a special focus on the Italian case. The article examines the geographical distribution and the prevailing forms of violence, highlighting the anonymous nature of the vast majority of such events. Moreover, it emphasizes the important role played by the local authorities, who are often confronted with criminal infiltrations and growing discontent among the citizenry. Finally, it compares past trends with those observed during the first quarter of 2023, identifying a slight decrease in events in Italy, while observing an increase in France and Greece.

Highest Threat of Violence in Italy’s Southern Regions

The highest level of violence against local officials in the EU is recorded in Italy, with a total of 238 events – three-fourths all events reported across the EU. Over the years, violence has remained relatively stable in the country, with 80 events recorded in 2020, 73 in 2021, and 85 in 2022. The targeting of local officials is a deeply rooted phenomenon in the Italian context. Between 1975 and 2015, an estimated 132 administrators were killed at the hands of militant organizations, organized crime, and other actors.6Senato della Repubblica, ‘Commissione parlamentare di inchiesta sul fenomeno delle intimidazione nei confronti degli amministratori locali,’ 3 March 2015 Yet, actions against local state representatives are not limited to physical violence. ACLED’s partner Avviso Pubblico (”Public Alert”), an Italian nonprofit organization that brings together municipalities and regions fighting against organized crime, estimates that local officials faced over 400 acts of verbal and physical intimidation, threats and violence in both 2020 and 2021.7Avviso Pubblico – Enti locali e Regioni contro mafie e corruzione, ‘Amministratori sotto tiro – Rapporto 2021,’ July 2022 Avviso Pubblico estimates for 2022 – not yet published at the time of writing – suggest that these trends have largely continued in 2022, despite a relative decline.

The most common form of targeting of local officials recorded in Italy by ACLED involves the destruction of public or private property, accounting for more than 90% of total events targeting local administrations. Property destruction is followed by physical assaults (12 events) perpetrated by violent mobs, often occurring on the occasion of public events, and organized attacks (four events) that remain unclaimed. In at least two cases, remotely activated explosive devices were used to target local municipalities. In February 2020, an improvised explosive device (IED) exploded in front of the accounting office of the mayor of Soleto in Puglia, damaging the building entrance.8La Repubblica, ‘Salento, bomba danneggia lo studio professionale del sindaco di Soleto,’ 12 February 2020 In October of the same year, an IED was detonated on the back of the town hall of Quartu Sant’Elena in Sardegna a few days before the municipal election.9ANSA, ‘Bomba al municipio di Quartu a tre giorni da elezioni,’ 22 October 2020 In another two events in 2021, bomb disposal experts intervened to defuse two IEDs.10Italpress, ‘Ordigno rudimentale con minacce a Musumeci nel Catanese,’ 5 September 2021 While violence, threats, and intimidations have been widely documented, for the majority of the violent incidents, the perpetrators are unknown. The only exception is represented by cases of violent crowds that physically assault members of their local administrations over personal grievances, often concerning their workplace or area of residency.

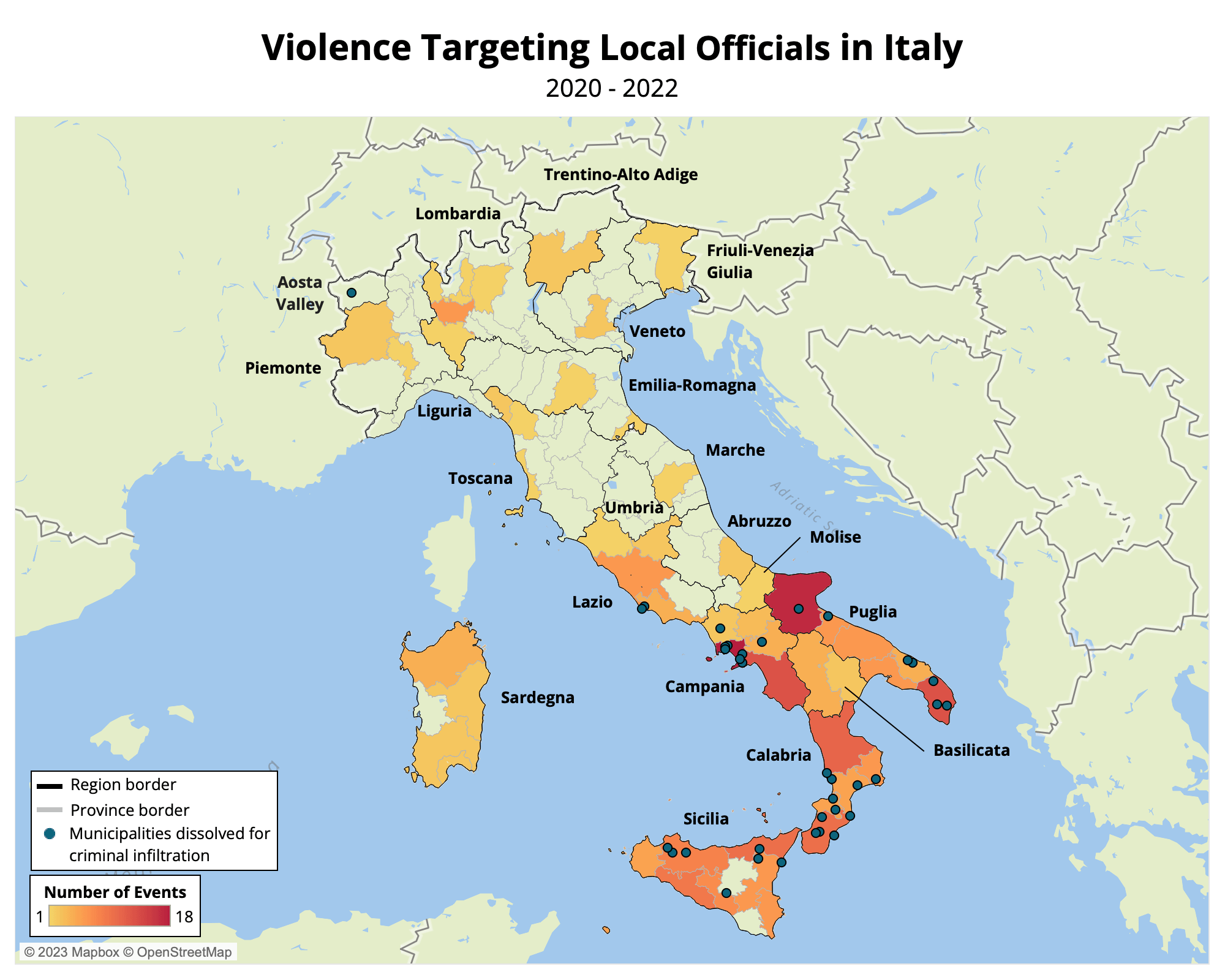

Local officials in Italy’s southern regions are the most exposed to violence, accounting for 75% of all events across the country between 2020 and 2022 (see map below). Puglia and Sicilia both recorded over 50 events, followed by Campania and Calabria at 40 and 37 events, respectively. These regions have also been the most marred by criminal infiltration. According to data published by the Italian Ministry of the Interior, 14 town councils were dissolved for criminal infiltration in 2021, while a total of 52 municipalities were entrusted to an extraordinary commission in the same year.11The extraordinary commission stays in power between 18 and 24 months. The total number of 52 accounts for both the 14 commissionings that occurred in 2021 and the existing ones from previous years. The goal of such commissions is to restore legality. They represent an extraordinary measure that is applied when there is a real danger that the activity of a municipality or other local government is bent to the interests of mafia-style organized criminal clans. Almost all municipalities dissolved for criminal infiltration in 2021 or that continued to be administered by an extraordinary commission from past years are located in the same Italian regions where the highest levels of violence occur, namely Puglia, Calabria, Sicilia and Campania. The same trend was reflected in 2020.12Openpolis, ‘Enti locali – Comuni commissariati, cosa è successo nel 2020,’ 15 January 2021; Ministero dell’Interno – Dipartimento per gli affari interni e territoriali, ‘Relazione del ministro dell’interno sull’attività delle Commissioni per la gestione straordinaria degli enti sciolti per infiltrazione e condizionamento di tipo mafioso,’ 2021

Local officials in southern Italy have long been a vulnerable target for organized criminal groups reaffirming their control over regions and municipalities and politicians seeking to eliminate their rivals. Among the most high-profile killings in Italy’s recent history are the assassinations of Sicilian governor Piersanti Mattarella, murdered by the mafia in 1980, and Francesco Fortugno, vice-president of Calabria’s regional assembly shot dead in Locri in Calabria in 2005 amidst a feud with a political competitor.13Senato della Repubblica, ‘Commissione parlamentare di inchiesta sul fenomeno delle intimidazioni nei confronti degli amministratori locali,’ 3 March 2015 Most actions, however, remain unclaimed, and investigations into the perpetrators and motives of violent acts against local officials are often inconclusive. Yet, the deep-rooted presence of organized criminal groups and their ability to influence politics in Italy’s southern regions suggest the possible intimidatory nature of such violence.14Gianmarco Daniele and Gemma Dipoppa, ‘Mafia, elections and violence against politicians,’ Journal of Public Economics, October 2017 Recent cases include an act of vandalism against the rear window of a car owned by a municipal councilor in Portopalo di Capo Passero in Sicilia in August 2022,15Giornale di Sicilia, ‘Intimidazione a un consigliere comunale di Portopalo: rotto il vetro della sua auto,’ 18 August 2022 and an arson attack against the car of a municipal councilor in the town of San Luca in Calabria in November of the same year.16Ansa, ‘Intimidazione ad assessore Comune San Luca, incendiata auto,’ 7 November 2022 Only in a limited number of instances, ACLED registers specific reference to the victims’ anti-organized crime agenda or to the suspicion that organized-crime groups may be behind these acts.

Bearing the Brunt of Political Discontent in the Rest of the European Union

In the rest of the EU, ACLED records a total of 77 events targeting local officials between 2020 and 2022. None of these events was lethal. The largest number of events took place in France, with 24 events, followed by Germany with 11 events. Greece and Spain record eight and seven events respectively, while another six occurred in both Cyprus and Bulgaria.

Destruction of public or private property accounts for approximately 50% of all violence recorded by ACLED in the rest of the EU. Around half of the events of this type include unclaimed arson attacks against cars owned by local officials and institutions. These are typically less guarded than local public facilities, and constitute a softer target for assailants seeking anonymity. The second most frequent form of targeting of local officials involves violent demonstrations and mob violence events, accounting for 40% of all acts of violence. This category includes events in which local authorities were assaulted during protest demonstrations and rallies or in retaliation for their policies. Other violent actions include the detonation of an IED outside the home of a former municipal councilor in Greece’s North Athens area and the explosion of a fragmentation grenade to damage a municipal building in Cyprus’ Limassol district.

Similarly to Italy, the overwhelming majority of events targeting local officials recorded by ACLED in the EU have no identified perpetrators, representing nearly three quarters of all cases. This is partly due to the fact that most acts of violence remained unclaimed at the time of reporting, making it difficult to assert the reasons triggering them. In a limited number of cases, however, motives can be traced back to specific local, national or regional developments. Notably, between 2020 and 2022, six events were driven by opposition to coronavirus restrictions. These included three events in France, where observers found that local authorities were also subject to an increase in verbal attacks and threats, despite most coronavirus-related decisions having been devised and made at the national level.17Mathilde Elie, ‘La crise sanitaire ravive les tensions envers les élus locaux,’ La Gazette des communes, 5 January 2022 Two coronavirus-related arson attacks against town halls were also recorded in Germany, and one in the Netherlands. This further suggests that local officials are, often in spite of themselves, on the front line of violence driven by frustration against national authorities.

While the anonymity of attacks on local officials remains the norm in the European context, several acts of violence can be linked to militant organizations. In the region’s recent history, militant organizations, such as the far-left Red Brigades in Italy or the separatist Euskadi Ta Askatasuna in Spain and National Liberation Front of Corsica in France, were responsible for the assassination of local state representatives from the 1970s through the early 2000s. More recently, several non-lethal violent actions were attributed to militant organizations.18Expansión, ‘ETA ha asesinado a 38 políticos desde 1968, a 22 de ellos en los últimos trece años,’ 7 March 2008; Senato della Repubblica, ‘Commissione parlamentare di inchiesta sul fenomeno delle intimidazione nei confronti degli amministratori locali,’ 3 March 2015 In France, three events were claimed by or attributed to anarchist groups, and one each to the far right and the Antifa movement. In Germany, ACLED records a minimum of three events attributed to far-left groups and another two to the Antifa movement between 2020 and 2022.

Unlike criminal groups, militant organizations often claim responsibility for their attacks, emphasizing their ideological opposition to the national government or the political affiliation of local officials, suggesting that they can come under attack not only for local policies they are associated with, but for national deliberations they are not directly involved in. Motives stated by militant organizations included the denunciation of a specific action carried out by local authorities, like the clearing of a homeless people’s camp or the prosecution of fellow militants by a local court.

Looking Forward

The total number of events targeting local officials in the EU has remained consistent during the first quarter of 2023, with almost as many events recorded by ACLED between January and March 2023 compared to the average of events per quarter of the previous year. Moreover, like in previous years, the majority of events recorded in the region had no identified perpetrators. However, this period was marked by a notable shift in the geographical distribution of the violence. For the first time, France produced a number of events closely tailing that of Italy – 34% (10 events) and 41% (12) of all EU events, respectively.

More events were recorded in France during January, February, and March 2023 than during the entire year prior. More than half of the targeting during the first quarter of 2023 occurred as part of the upsurge in demonstration violence following the French government’s decision to push through its pension reform bill on 16 March 2023. While national assembly members were also exposed to violence in this context,19TF1 Info, ‘Retraites : menaces, incivilités… les agressions contre les élus se multiplient,’ 30 March 2023 observers have found that local officials – traditionally seen as advocates of local citizens’ interests and conveyors of their grievances – represent a more attainable and increasingly exposed target for acts of political violence against the backdrop of rising popular discontent and distrust of national institutions.20Benoît Flo’ch, ‘‘I wasn’t elected for this’: French mayors in firing line as violence and death threats on the rise,’ Le Monde, 26 November 2022; Benoît Flo’ch, ‘Le nombre d’agression d’élus marque une hausse,’ Le Monde, 15 March 2023; Roger Cohen and Liz Alderman, ‘French Anger Shifts From Pension Law to Focus on Macron,’ New York Times, 24 March 2023 The French government’s intention to proceed with a fast-paced reformist agenda containing other “unpopular reforms” may continue to underlie this phenomenon in 2023.21Les Échos, ‘Il n’y aura “pas de retraite” pour les réformes, prévient Olivier Véran,’ 26 March 2023; BFM TV, ‘Emmanuel Macron assume “des réformes impopulaires” pour “créer de la richesse et la redistribuer”,’ 27 April 2023

Additionally, two arson attacks targeting local officials were reported during the first quarter of 2023 in small municipalities of Corsica’s Ajaccio arrondissement. These actions were attributed to the newly formed Clandestine Youth of Corsica (GCC) group. Both events suggest a shift in the tactics adopted by the revived anti-French clandestine Corsican nationalist movement, which until then, had primarily targeted holiday homes of mainland France residents.22Paul Ortoli, ‘En Corse, la compétition entre deux groupes clandestins brouille le jeu politique,’ Le Monde, 5 April 2023 Another arson attack – also attributed to GCC – targeted the rental villa belonging to a deputy mayor of Ajaccio on the night between 9 and 10 April 2023. Over the past decades, several state officials were killed in the island of Corsica at the hands of armed separatists and other unknown gunmen.23Antoine Albertini, ‘La Corse frappée par un troisième assassinat de personnalité publique en six mois,’ Le Monde, 26 April 2013; Marie-Aude Bonniel, ‘Il y a 25 ans, Claude Érignac, préfet de Corse était assassiné,’ Le Figaro, 5 February 2018

In Italy, ACLED records a decrease of violence against local officials during the first quarter of 2023, as only 12 events were recorded, in comparison with 20 events during the same period in 2022, 19 in 2021, and 33 in 2020. Despite this drop, ongoing acts of violence in southern Italy suggest that intimidatory tactics will continue to be an ever-present threat for local officials. The perpetrators of all intimidatory acts recorded by ACLED in Italy in the first quarter of 2023 remained unidentified, following the trends registered in past years.

Similarly to France, in Greece, ACLED records as many events targeting local officials in the first quarter of 2023 (four) as in 2022, although in all cases perpetrators were unidentified. While the events observed in the country appear to be driven by distinct incentives, they took place in a polarized socio-political environment marked by a widespread distrust of political institutions and normalization of political violence,24Ekathimerini.com, ‘Poll: most Greek voters deeply distrust all institutions,’ 8 April 2023 likely to further expose local authorities in the future.

Overall, even if these events are largely non-lethal, the persistence of these threats across the EU in 2023 suggest that this phenomenon is unlikely to be brushed off from the continent. While the EU continues to be a largely peaceful region, these trends indicate that local institutions continue to be vulnerable to acts of violence, intimidation, and hate speech perpetrated by a host of criminal and militant groups and members of polarized citizenries, thus bearing the brunt of criminal infiltrations and public discontent.

Visuals in this report were produced by Ciro Murillo