Special Issue

Administering Violence

An ACLED Special Project on Violence Targeting Local Officials

Published: 22 June 2023

Databox: Violence Targeting Local Officials

Download the new ACLED data on violence targeting local government officials around the world.

This file contains events classified as violence targeting local government officials with the ‘local administrators’ tag, where 1) violence is used against local officials or administrators; or 2) property owned by (or symbolic of) local government administration is targeted or destroyed. Local officials are understood as administrators who are part of subnational government institutions, from the first-level administration division down to cities, towns, and villages. Examples of local officials are: elected or appointed officials or representatives from subnational state institutions (including former); civil servants, election officials and poll workers, local justice officials, and other local authorities; and relatives of local officials or representatives. The tag also applies to attacks that target property linked to government functions or owned by local officials, including local government buildings, courts, local election centers, and/or adjacent public or private property. For more information, check the methodology note on the ‘local administrators’ tag. Please note differences in time period coverage per country and region. A full list of country-year coverage is available here.

Violence Targeting Local Administrators ( 13 June 2025 )

Executive Summary

Local government officials – including governors, mayors, councilors, and other civil servants – routinely come under attack by a wide array of armed actors, from cartels waging turf wars in Mexico to Russian occupying forces in Ukraine. These attacks are perpetrated to constrain, intimidate, or punish civilian administrators who oversee service provision, public security, and other government functions. Their consequences include undermining social cohesion and discouraging participation in public life in affected communities.

To better monitor this threat and its impacts around the world, ACLED has launched a special project to systematically identify incidents of political violence targeting local officials. The project’s inaugural report provides an overview of the new data with in-depth analysis of six case studies that illustrate the scale and variation in attacks on local government: Mexico, Ukraine, the European Union, South Africa, Brazil, and the Philippines.

Key Findings

- In total, ACLED records more than 2,100 incidents of violence targeting local government officials and institutions in nearly 100 countries around the world in 2022.

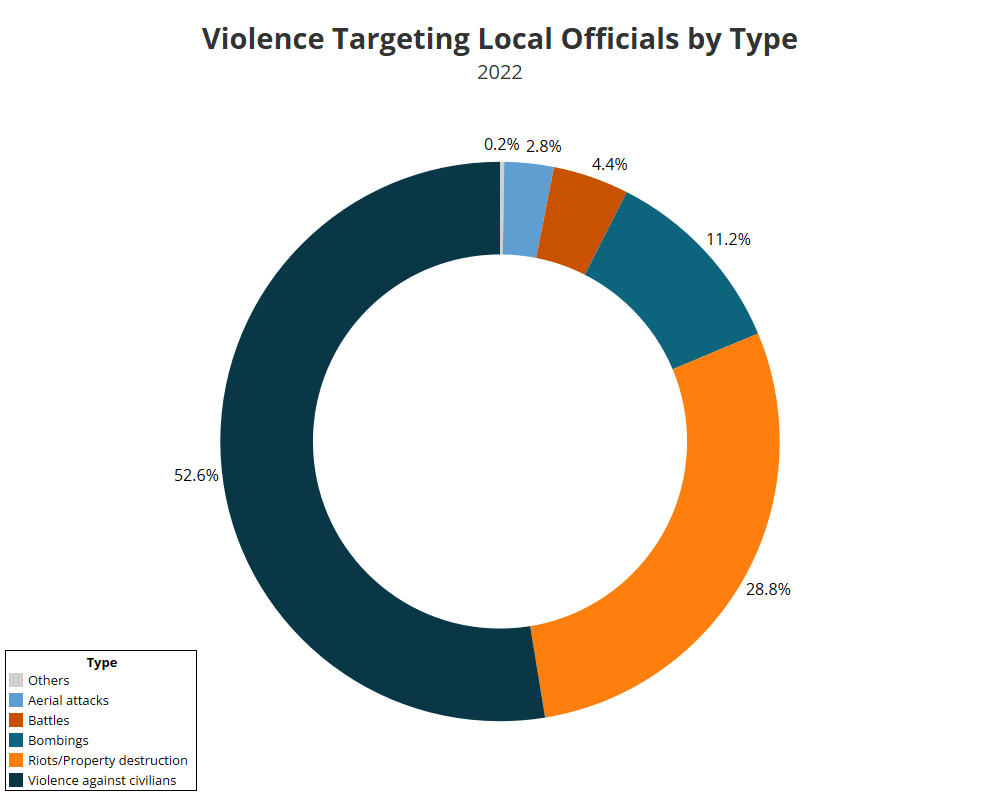

- Direct attacks on unarmed officials, such as stabbings and shootings, account for over 50% of all reported events. Other common forms of violence include riots and mob attacks, property destruction, bombings, and abductions.

- The regions with the highest incident counts in 2022 were Southeast Asia, Europe, and South Asia, together accounting for approximately 50% of all events.

- The countries with the highest incident counts in 2022 were Myanmar, Mexico, Ukraine, India, and the Philippines, with each registering over 100 events. ACLED data show that acts of political violence and intimidation against local officials are not limited to areas affected by active wars, but are also widespread in less conflict-affected countries with democratic institutions, such as Italy and South Africa.

- Drivers of the violence include struggles over territorial control in conflict zones, militarized political competition, and the disruptive influence of organized crime and corruption on local government.

Violence Targeting Local Officials: A Growing and Pervasive Threat

Around the world, local officials are routinely targeted for violence. Governors, mayors, councilors, and local civil servants come under attack by a wide range of violent agents, such as states, insurgents, militias, criminal groups, mobs, and rioters. These attacks are perpetrated to constrain, intimidate, or punish civilian administrators who oversee service provision, public security, and other local government functions. Their consequences include undermining social cohesion and discouraging participation in public life in affected communities.

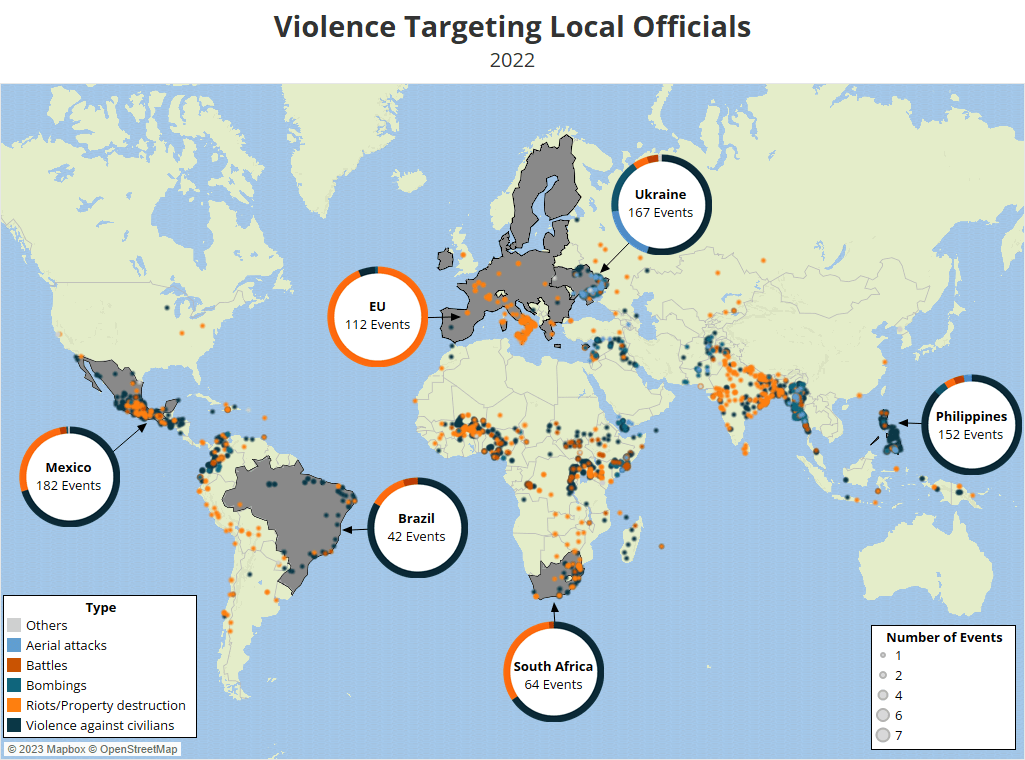

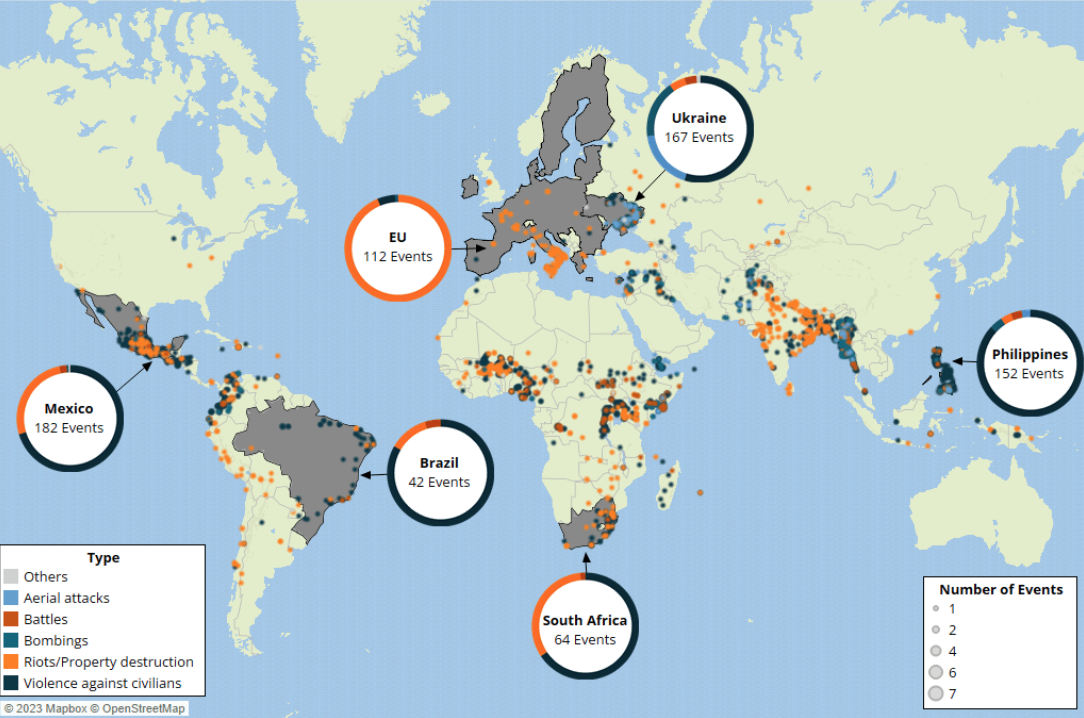

To monitor this growing and pervasive threat, ACLED has launched a new project to systematically identify incidents of political violence targeting local government officials.1As part of this project, ACLED is introducing a new tag to the global dataset that flags events of violence targeting local administrators for ease of reference, in addition to creating a corresponding data file on our Curated Data page that allows users to download the subset directly. See inset box below for more information. ACLED data collection demonstrates that this violence is widespread and significant. In 2022, ACLED records over 2,100 incidents of violence targeting local officials in nearly 100 countries around the world (see map below). These actions are only a subset of all political violence that occurs globally, but they represent a serious threat to state authority and good governance in local communities, whose representatives face dangers from an array of armed actors.

Attention to such violence is increasing and typically concentrates on large-scale events. The abductions of dozens of Ukrainian mayors, the killings of officials in Mexico and South Africa, and the intimidation of hundreds of administrators throughout Europe have raised concerns among policymakers seeking to protect local state representatives from violence. The widespread nature of the threat, which affects countries experiencing different degrees of conflict, requires a systematic examination of the phenomenon globally (for more on global patterns of conflict more broadly, see the ACLED Conflict Severity Index).

In this inaugural special issue report, we explore a range of case studies to shed light on the variety of security risks faced by local public officials. Across all these cases, local officials find themselves under pressure to cooperate with, or concede to, hostile state actors, opposition groups, criminal organizations, and other armed actors. We find three prevailing logics behind these attacks, which are as varied as the contexts in which they occur.

A first logic applies primarily to countries engaged in active wars, as state forces and insurgent groups aspire to seize territorial control from their enemies. In these contexts, attacks against local officials are designed to weaken the enemy’s grip on local populations, impose territorial control, and deter local elites from collaborating with the enemy. A second logic involves violent political competition. Here, aspiring officeholders aim to eliminate potential rivals, using militias or hired gangs to subdue competitors. A third related logic involves the penetration of organized criminal groups into local government. Local authorities are seen as potential accomplices or obstacles, and violence is used to obtain their collaboration and influence local decision-making.

The cases outlined in this special issue illustrate this host of challenges. In Ukraine, the Russian invasion has shifted the spectrum of threats faced by local officials who are caught in an armed struggle over territorial control and authority. Electoral competitions have contributed to heightened violence against officials in the Philippines, South Africa, and Brazil. Officials in Mexico and Italy operate in an environment where criminal organizations have permeated local institutions, blurring the lines between political and criminal violence. As these case studies show, however, these logics rarely occur in isolation from one another, and multiple logics may coexist in the same space.

Who Targets Local Officials?

In many countries, being a local official or administrator is a risky job. They are the government representatives who are most proximate to a state’s citizens. Governors, mayors, councilors, and other public officials carry out a host of government functions at the local level. These government officials are thus key state actors overseeing public service delivery, security provision, voting processes, and decision-making at the local level. Their functions range from enforcing policies of the national government to the administration of local budgets and justice. In doing so, they contribute to further government outreach across territory, and operate as intermediaries with local communities. Local authorities have an important role in maintaining regime stability, administering security forces and service provision, while also absorbing dissatisfaction with the national government.2Tore Wig & Andreas Forø Tollefsen, ‘Local institutional quality and conflict violence in Africa,’ Political Geography, 53, 2016, pp. 30-42

Local officials are often the first point of engagement for violent armed groups intent on undermining the authority of a state or influencing local governance. Many of these groups target officials to serve their political goals. This practice is widespread and evident over time. During the Second World War, German occupation authorities routinely killed Ukrainian authorities that refused to carry out orders.3Markus Eikel & Valentina Sivaieva, ‘City Mayors, Raion Chiefs and Village Elders in Ukraine, 1941-4: How Local Administrators Co-Operated with the German Occupation Authorities,’ Contemporary European History, 23 (3), 2014, pp. 405–28 In Italy, the Sicilian Mafia murdered dozens of local administration officials deemed hostile or unreliable.4Senato della Repubblica, ‘Commissione parlamentare di inchiesta sul fenomeno delle intimidazione nei confronti degli amministratori locali,’ 3 March 2015 Communist guerrilla forces in Vietnam engaged in the killing of several representatives of the United States-backed government of South Vietnam.5Stephen T. Hosmer, ‘Viet Cong Repression and Its Implications for the Future,’ Rand Corporation, 1970 Other rebel and separatist actors – from Euskadi Ta Askatasuna in Spain to the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia – likewise carried out targeted assassinations of local government officials.6La Nacion, “Un plan diabólicamente eficaz,” 15 July 2002; Expansión, ‘ETA ha asesinado a 38 políticos desde 1968, a 22 de ellos en los últimos trece años,’ 7 March 2008 These practices continue into the present day, and suggest similarly broad motivations for multiple types of groups to target local authorities.

The abduction and assassination of dozens of Ukrainian mayors following the Russian invasion in 2022 drew widespread criticism from European institutions.7Twitter @JosepBorrellF, 13 March 2022; Council of Europe, ‘Congress President condemns the continuing abduction of Ukrainian local elected representatives,’ 5 September 2022 In Mexico, cartels are reported to be behind the killing of hundreds of mayors over the past decades.8Ioan Grillo, ‘Why Cartels Are Killing Mexico’s Mayors,’ 15 January 2016 The use of violence against local authorities in these and other conflict-affected contexts reportedly reflects the changing tactics of cartels and guerrilla groups.9Associated Press, ‘Ethiopia says 22 regional officials killed by Tigray rebels,’ 27 May 2021; Richard C. Paddock, ‘Assassinations Become Weapon of Choice for Guerrilla Groups in Myanmar,’ The New York Times, 6 June 2022; David L. Stern, ‘Ukrainian hit squads target Russian occupiers and collaborators,’ The Washington Post, 8 September 2022 Elsewhere, media and civil society organizations in stable democracies, such as France, New Zealand, and the United States, have raised concerns over the increasing harassment and intimidation of local officials, including mayors, councilors, election workers, and other elected officials.10Patrick Sisson, ‘Why Local Officials Are Facing Growing Harassment and Threats,’ Bloomberg, 29 June 2022; Stefan Dimitrof, ‘Survey reveals local body elected officials targeted in bullying and discrimination attacks,’ Te Ao Maori News, 18 July 2022; Benoît Floc’h, ‘’I wasn’t elected for this: French mayors in firing line as violence and death threats on the rise,’ Le Monde, 26 November 2022

These various cases are crucial to acknowledge because of the widespread nature of the problem. It is occurring in war-affected countries as well as in those with thriving democratic institutions.11Kim Thomas, ‘The rule of the gun: Hits and assassinations in South Africa, 2000-2017,’ University of Cape Town and Global Initiative against Transnational Organized Crime, March 2018; Mariana Carvalho, ‘Why are there so many political assassinations in Brazil?,’ Political Violence at a Glance, 13 July 2021; Peter Kreuzer, ‘Killing Politicians in the Philippines: Who, Where, When, and Why,’ Hessische Stiftung Friedens- und Konfliktforschung, 2022 Local authorities are the ‘cogs’ of the system, and attacks on them represent larger and fundamental issues within the body politic – even more so as the perpetrators often remain unknown and enjoy impunity.

Why Are Local Officials Targeted?

The significance of these acts of violence and their drivers have attracted considerable research interest. Yet, despite a growing body of research, there is a lack of data at the global level, and this has prevented a systematic analysis of violence against local administration officials around the world. Measuring this threat allows us to track its patterns and impact globally, and elaborate effective policy responses. To date, violence against local officials has largely featured in case studies on organized crime and insurgent groups, highlighting their distinct features rather than analogies around the timing, geography, or meaning of these actions.

There are multiple drivers of violence against local officials. Some scholars have linked this violence to the prevalence of corrupt networks in local institutions. Where criminal organizations have penetrated local government, state authorities face a deadly dilemma: giving in to corruption (plata) or succumbing to violence (plomo).12Ernesto Dal Bó, Pedro Dal Bó & Rafael Di Tella, ‘“Plata O Plomo?”: Bribe and Punishment in a Theory of Political Influence,’ The American Political Science Review, 100 (1), 2006, pp. 41–53 Among others, Mexico and Italy have provided case studies to test the hypothesis that elections, incidence of organized crime, and alignment between national and local institutions can affect the frequency and lethality of attacks against local officials.13Salvatore Sberna & Elisabetta Olivieri, “‘Set the Night on Fire!’ Mafia Violence and Elections in Italy”. APSA Annual Meeting Paper, 2014; Gianmarco Daniele & Gemma Dipoppa, ‘Mafia, elections and violence against politicians,’ Journal of Public Economics, 153, 2017: pp. 10–33; Alberto Alesina, Salvatore Piccolo & Paolo Pinotti, ‘Organized Crime, Violence, and Politics,’ The Review of Economic Studies, 86 (2), 2019: pp. 457–499; Guillermo Trejo & Sandra Ley, ‘High-Profile Criminal Violence: Why Drug Cartels Murder Government Officials and Party Candidates in Mexico,’ British Journal of Political Science, 51 (1), 2021, pp. 203-229

A related driver of violence against local officials is the widespread nature of political corruption. Corrupt, illegal exchanges are not limited to developing countries or authoritarian regimes, but extend to countries with established democratic institutions.14Donatella Della Porta & Alberto Vannucci, ‘Corrupt Exchanges. Actors, Resources, and Mechanisms of Political Corruption,’ 1999 Local institutions are often permeable to the actions and interests of criminal organizations, which seek to access state institutions to protect their illegal businesses. Exercising influence over local authorities through the threat or the use of violence thus provides an opportunity for a host of armed actors – whether political or criminal – to ultimately assert their supremacy over local institutions and degrade the quality of local governance.15Andreas Schedler, ‘Making Sense of Electoral Violence: The Narrative Frame of Organised Crime in Mexico,’ Journal of Latin American Studies, 54 (3), 2022, pp. 481–507 While criminal cartels rarely claim responsibility for their actions, preferring anonymity, their presence may also provide cover to other actors who can take advantage of impunity to settle their scores against rival elites.

In other contexts, violence against local officials is a function of competition within local institutions and political parties.16David Bruce, ‘A Provincial Concern? Political Killings in South Africa,’ SA Crime Quarterly, 45, 2013; Kim Thomas, ‘The rule of the gun: Hits and assassinations in South Africa, 2000-2017,’ University of Cape Town and Global Initiative against Transnational Organized Crime, March 2018; Megan Turnbull, ‘Elite Competition, Social Movements, and Election Violence in Nigeria,’ International Security, 45 (3), 2021, pp. 40–78 There is tremendous competition for government positions, and the benefits they accord to those elected or appointed to such posts. In response to these challenges, contests for local positions have often become militarized and violent.17William Reno, ‘Clandestine Economies, Violence and States in Africa,’ Journal of International Affairs, 53 (2), 2000, pp. 433-459 In fact, in several contexts, violence happens both within and between political parties. Some local elites have responded to this competition by hiring and retaining armed militias and criminal gangs with the aim of suppressing competition.18William Reno, ‘The Politics of Violent Opposition in Collapsing States,’ Government and Opposition, 40 (2), 2005, pp. 127-151; Valba Felbab-Brown, ‘The rise of militias in Mexico: Citizens’ security or further conflict escalation?,’ Brookings, 9 December 2015 These groups, operating at the behest of elites to hold or contest formal government positions, are ultimately responsible for large increases in violence across the world (see also the ACLED Conflict Severity Index).

Nearly all countries have established local government institutions, with most posts situated at the lower levels of the administration.19OECD, ‘Subnational governments around the world,’ 2016 Yet, local officials do not enjoy the same levels of protection that higher echelons of a state do, and are therefore more exposed to acts of violence, intimidation, and hate speech. At the same time, lower salaries and looser alignment with the national government may increase the opportunities for corruption and dissension. In other words, there is an expectation that local authorities are replaceable, and there is little job security in such positions. National governments, as well as non-state armed actors, know this and operate accordingly, using violence to influence, coerce, or punish officials.

Finally, state and non-state actors attack local officials to impose control over local territories and populations. Territorial control requires a degree of cooperation between occupying forces and local elites, who are key actors in enabling recruitment and suppressing popular opposition. Yet, resistance and insurgent groups also engage in this form of violence. Here, the goals are multiple: to punish collaborators of the regime and deter others that might follow in their footsteps, to break a regime’s local governance system, or seize authority locally to demonstrate the lack of government reach and presence.

By the Numbers: Violence Against Local Officials in 2022

ACLED records more than 2,100 violent events targeting local officials and institutions around the world in 2022.20Data as of June 2023; ACLED is a living dataset and exact figures are subject to change as new information becomes available. The count includes the following event and sub-event types: Battles (Armed clash, Government regains territory, Non-state actor overtakes territory); Explosions/Remote violence (Air/drone strike, Grenade, Remote explosive/landmine/IED, Shelling/artillery/missile attack, Suicide bomb); Protests (Excessive force against protesters); Riots (Mob violence, Violent demonstration); Strategic developments (Disrupted weapons use, Looting/property destruction); Violence against civilians (Abduction/forced disappearance, Attack, Sexual violence). For more on each of these event and sub-event types, see the ACLED Codebook. Direct attacks on unarmed local officials account for over half of all recorded events (more than 1,110). These include beatings, stabbings, shootings, and other physical violence that resulted in deaths or injuries. Among reported incidents of violence targeting local officials are also kidnappings and forced disappearances – approximately 200 events in 2022 – as well as acts of sexual violence. In nearly 100 events, attacks against local officials triggered clashes with security forces or armed bodyguards.

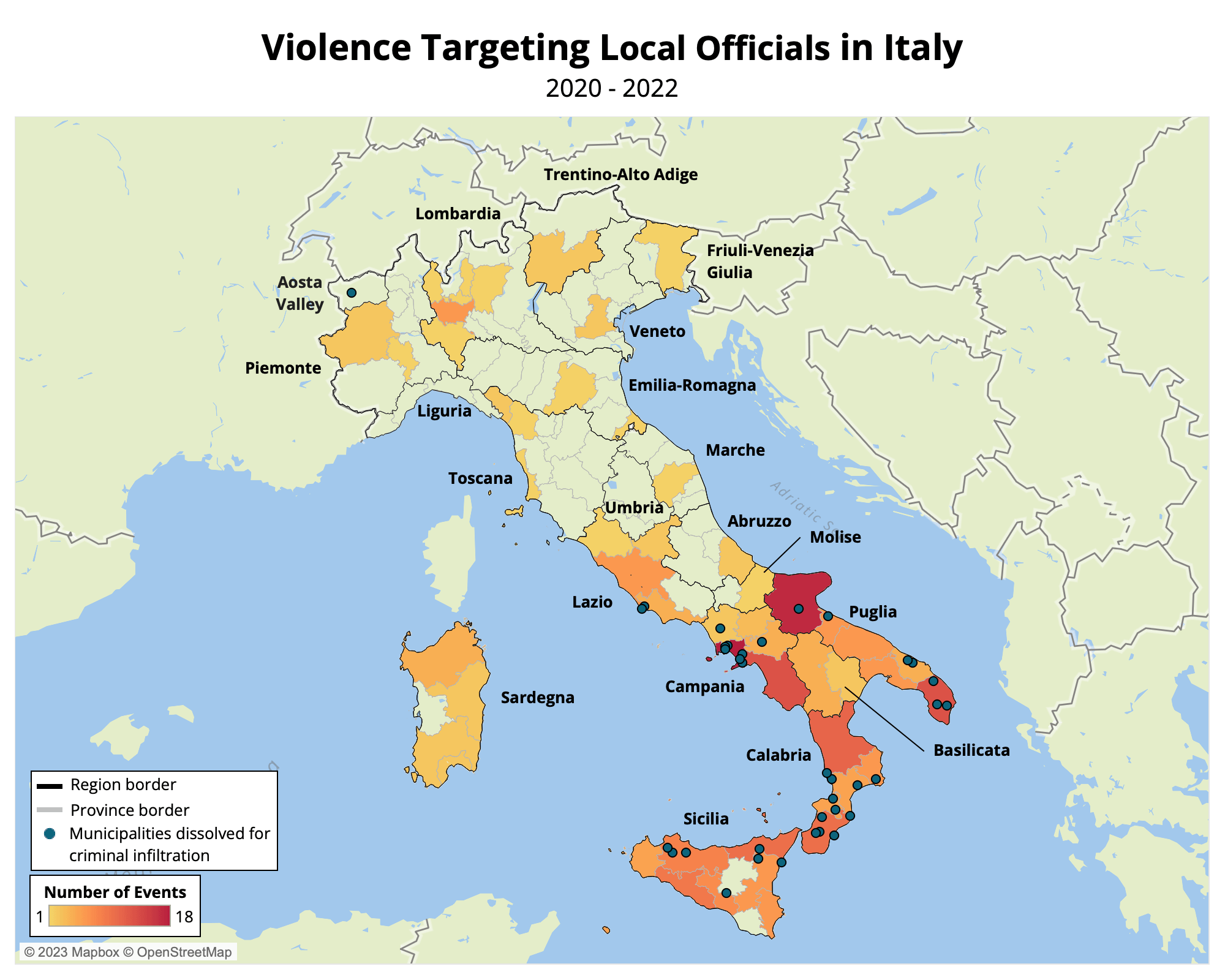

Another common form of violence recorded by ACLED includes actions perpetrated by spontaneous, non-organized mobs or groups of violent demonstrators. Mobs and rioters targeted local administrations in over 350 events within and outside demonstration contexts last year. These incidents typically involve physical assaults on public officials or the storming of administration buildings. Nearly 50% of these events took place in India, Mexico, and Nepal. In approximately 260 events, assailants destroyed public or private property belonging to local governments or officials without resulting in death or injury. Such acts of intimidation were common in countries as diverse as Italy, Burkina Faso, and Myanmar.

The use of explosive devices is another frequent strategy used by a host of armed actors to target or intimidate local administrators. ACLED records more than 230 bombing events impacting local officials in 2022, three-quarters of which took place in just three countries: Myanmar, Somalia, and Ukraine. In these active conflict contexts, rebel groups and militants often carried out bomb and suicide attacks to inflict damage on the state and its representatives. The same goal also motivates the targeting of local officials and administrators through aerial and artillery attacks, such as airstrikes and shelling, which account for approximately 60 events, largely confined to Ukraine and Myanmar.

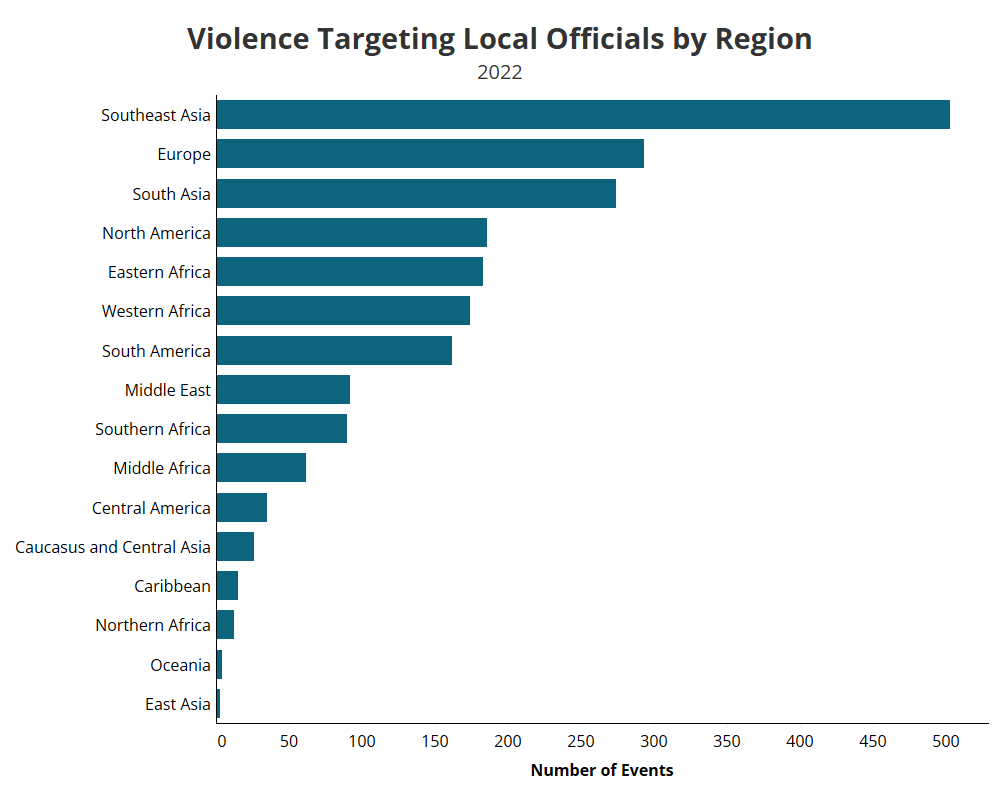

Overall, the regions registering the highest number of incidents of violence targeting local officials are Southeast Asia, Europe, and South Asia (see chart below). These three regions account for approximately half of all events recorded in 2022. Myanmar, Mexico, Ukraine, India, and the Philippines are the countries that saw the highest number of incidents last year, with each registering over 100 events.

Trends vary widely among regions and countries. In South Asia, incidents are predominantly spontaneous acts of rioting and property destruction resulting in a limited number of reported fatalities. Attacks against local officials were instead far deadlier in Myanmar, Mexico, Ukraine, and the Philippines, where direct physical attacks carried out by state forces, militias, rebel groups, and armed criminal organizations are more common. The dataset also shows that violence targeting local officials is not limited to countries experiencing active conflict. In fact, Italy and South Africa, which feature among the 10 countries where local officials are most at risk, respectively registered more than 80 and 60 events in 2022, together exceeding the Middle East region as a whole.

In this special issue, we examine patterns and drivers of violence targeting local officials across six contexts: Mexico, Ukraine, the European Union, South Africa, Brazil, and the Philippines. These case studies illustrate the variety of threats faced by local officials around the world, highlighting differing homegrown modalities and logics of violence.

A New Tag for Violence Against Local Officials

As part of this project, ACLED has instituted a new system to track violence against local administration officials.21This tag will be live in the data as of the weekly update through 23 June 2023. Using the tag ‘local administrators’ under the relevant column in the ACLED dataset, users can isolate events where 1) violence is used against local administrators or 2) property owned by (or symbolic of) the local administration is targeted or destroyed. Local government officials are understood as administrators who are part of subnational government institutions, from the first-level administration division down to cities, towns, and villages. The tag does not apply to members of the central government or other national-level administrations.

Examples of local officials included in the tag are: elected or appointed officials or representatives from subnational state institutions (including former); civil servants, election officials and poll workers, local justice officials, and other local authorities; relatives of local officials or representatives. The tag also applies to attacks that target property linked to government functions or owned by local officials, including local government buildings, courts, local election centers, and/or adjacent public or private property.

The tag does not apply to: members of national-level institutions; civil servants working for the national government; non-state or other informal authorities, unless they are recognized as acting in a formal capacity; election commission employees and poll workers who are not explicitly described as local officials; local political leaders that do not occupy a formal role at the time of the event (including candidates for local office); current or former local security services like municipal police and/or other local, regional or state security forces.

This project is ongoing, and the tag is now incorporated into ACLED’s standard real-time data collection, with regular weekly updates. Violence targeting local officials and administrators is tracked for all countries covered by ACLED back to January 2018, or their start-date for ACLED coverage, whichever is most recent (historical coverage earlier than 2022 varies by country and region). For more information about the ‘local administrators’ tag, see this methodology note.

Case Studies:

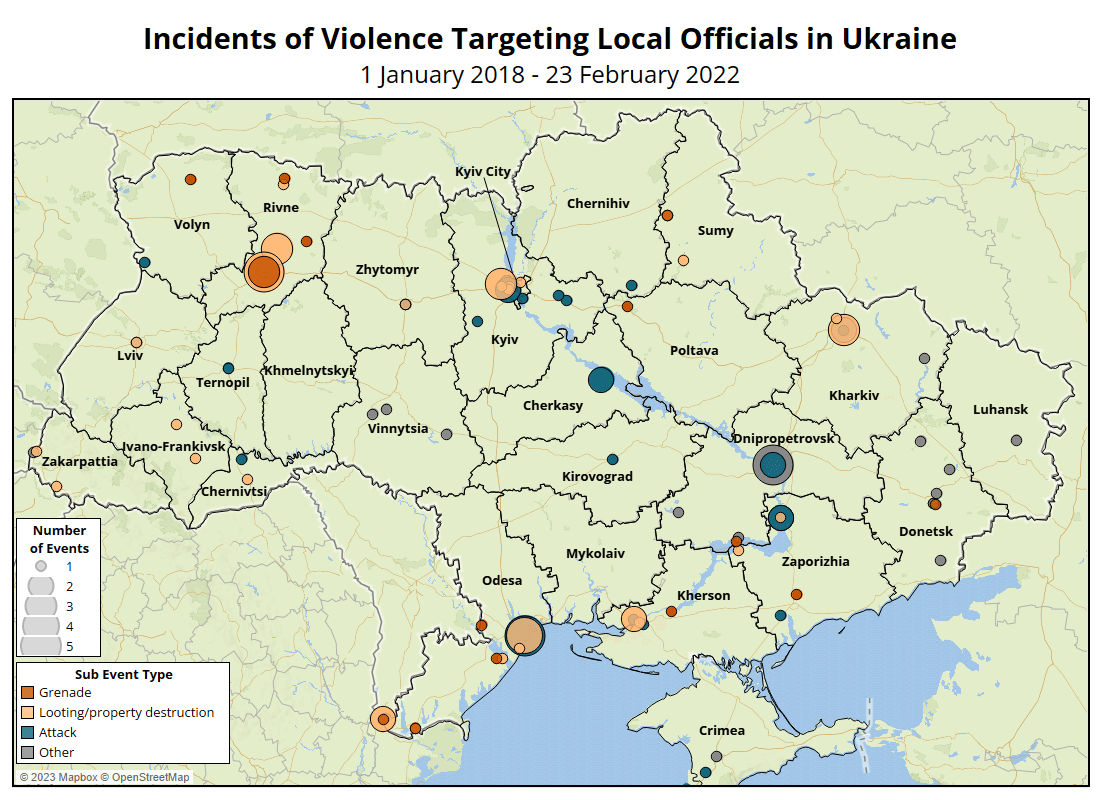

In the year since Russia launched its full-scale invasion, the number of incidents targeting local officials has spiked – a trend that was particularly pronounced during the first months of the war. Local authorities became targets of the Russian occupation forces due to their role as officials in the Ukrainian administration and at the same time, local authorities considered to be linked to the Russian occupation became the target of groups loyal to the Ukrainian government. As the war wages on, this type of violence shows few signs of abating.

Between 2020 and 2022, incidents of violence targeting local officials were reported in at least 16 out of 27 EU countries. Approximately 85% of these attacks have been committed anonymously. Though largely non-lethal, the persistence of these threats across the EU, and the rise in countries like France and Greece, emphasize that local authorities are very often bearing the brunt of political discontent.

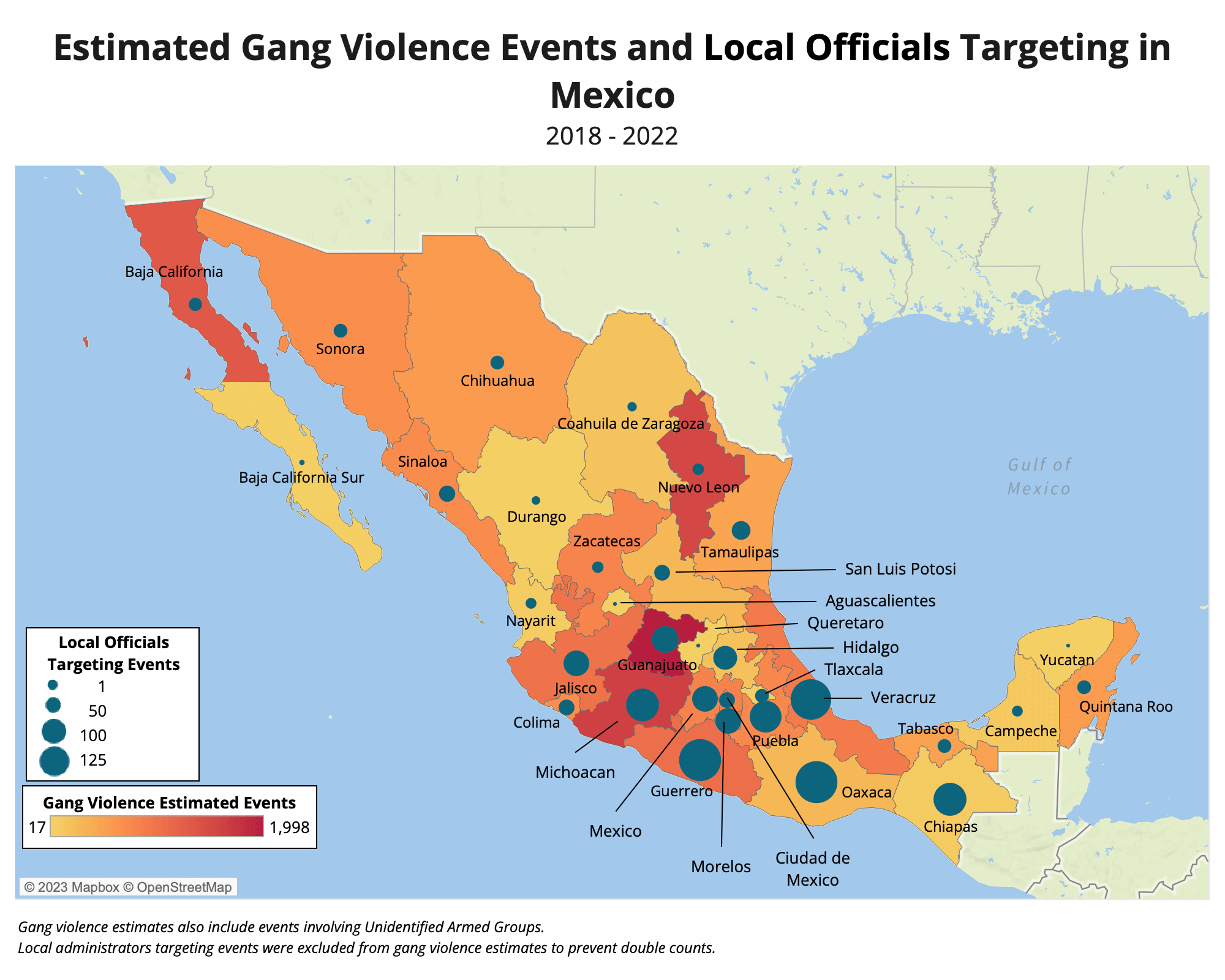

ACLED records incidents of violence targeting local officials across all 32 states in Mexico. However, some of the highest levels of violence are reported in Oaxaca and Chiapas states, where ACLED data show relatively low levels of events related to gang violence – challenging the narrative that political violence in Mexico is a function of organized crime alone. As political competition and power dynamics contribute to widespread violence, particularly around election cycles, risks are likely to escalate ahead of the next general elections scheduled for June 2024.

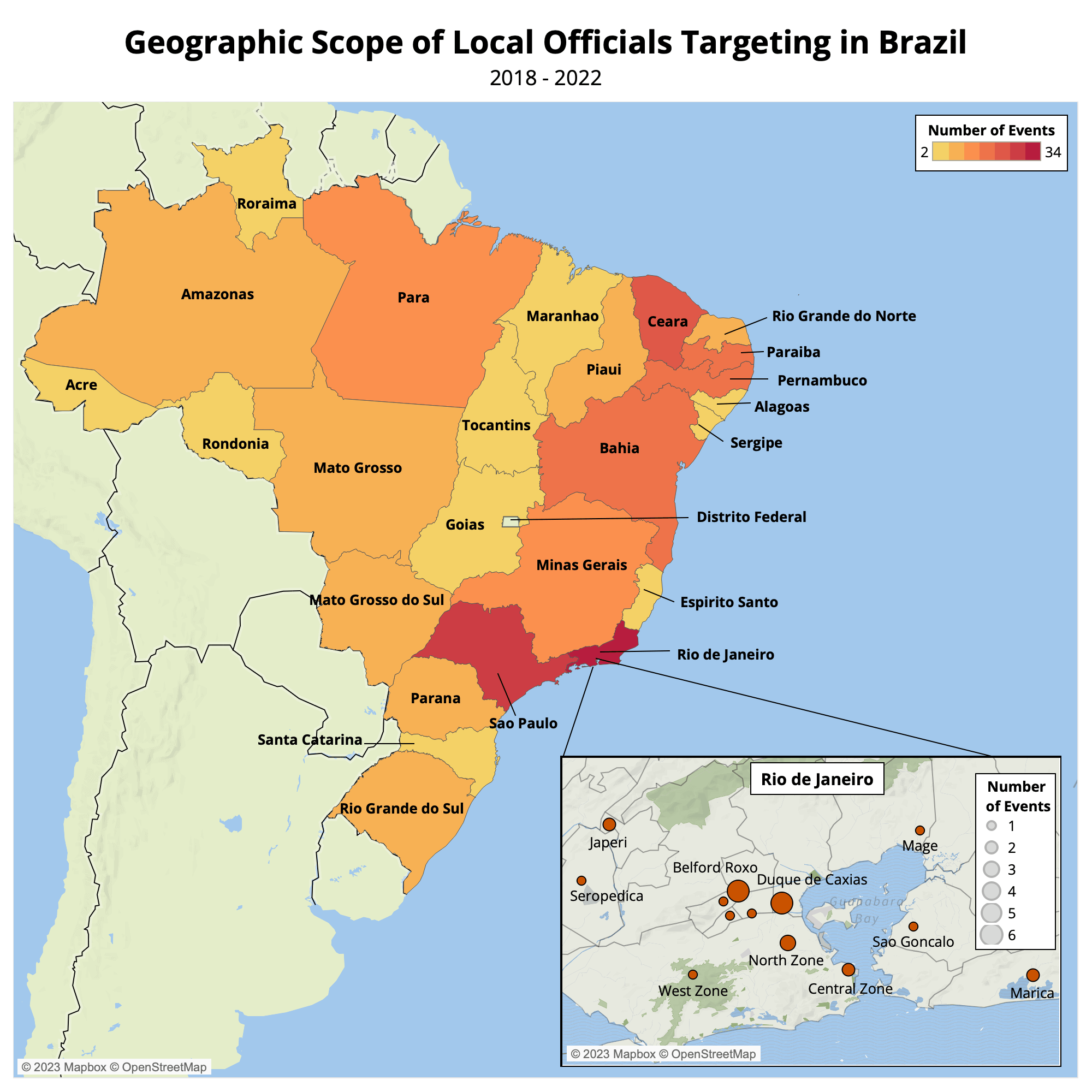

Violence targeting officials in Brazil is most pervasive and deadly at the municipal level, and risks are heightened during local elections. Ongoing investigations into the interference of organized crime in the latest vote in the states of Piauí and Rio de Janeiro point to continuous involvement of gangs and militias in electoral politics. Heading into the 2024 municipal elections, heightened tensions stoked by national politics and the relationship between organized criminal groups and some local authorities are likely to amplify existing party tensions and exacerbate local political rivalries.

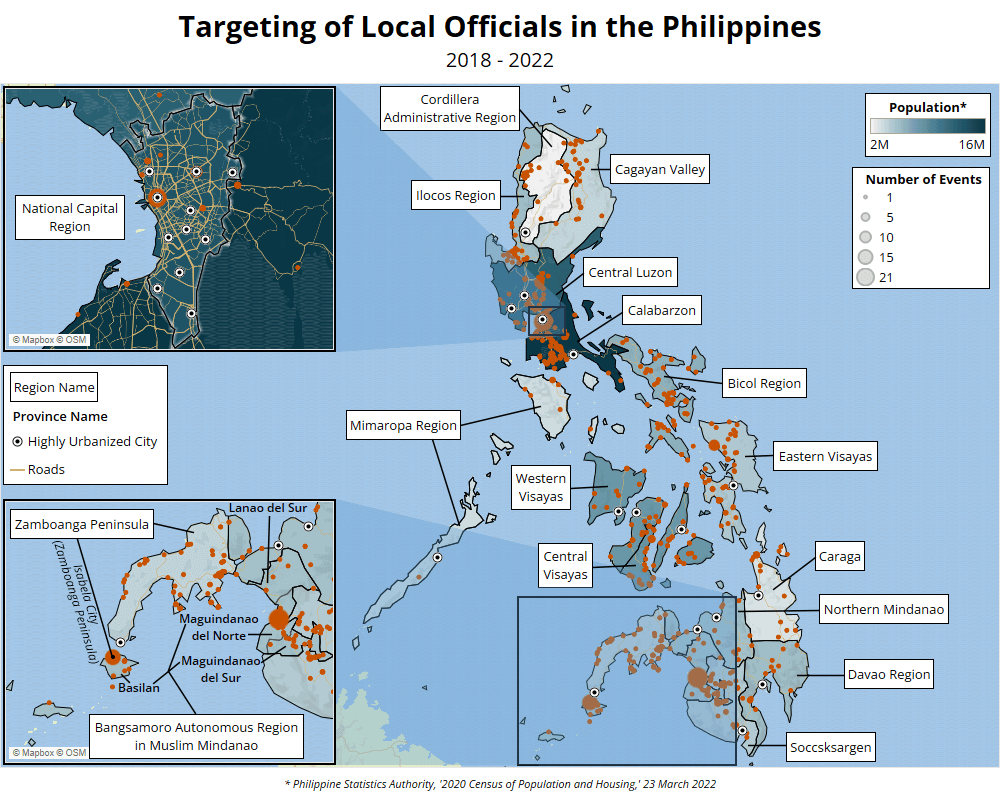

The Philippines has historically grappled with a high – and lethal – level of violence targeting local officials. Such violence is heavily concentrated in rural areas, particularly the BARMM, and especially during election periods. However, while the Philippines is home to many conflicts, a large percentage of violence targeting local officials occurs outside of such conflicts and can be tied to electoral competition, the proliferation of political dynasties, and the domination of ‘strong families’ who find recourse in violence to secure their interests.

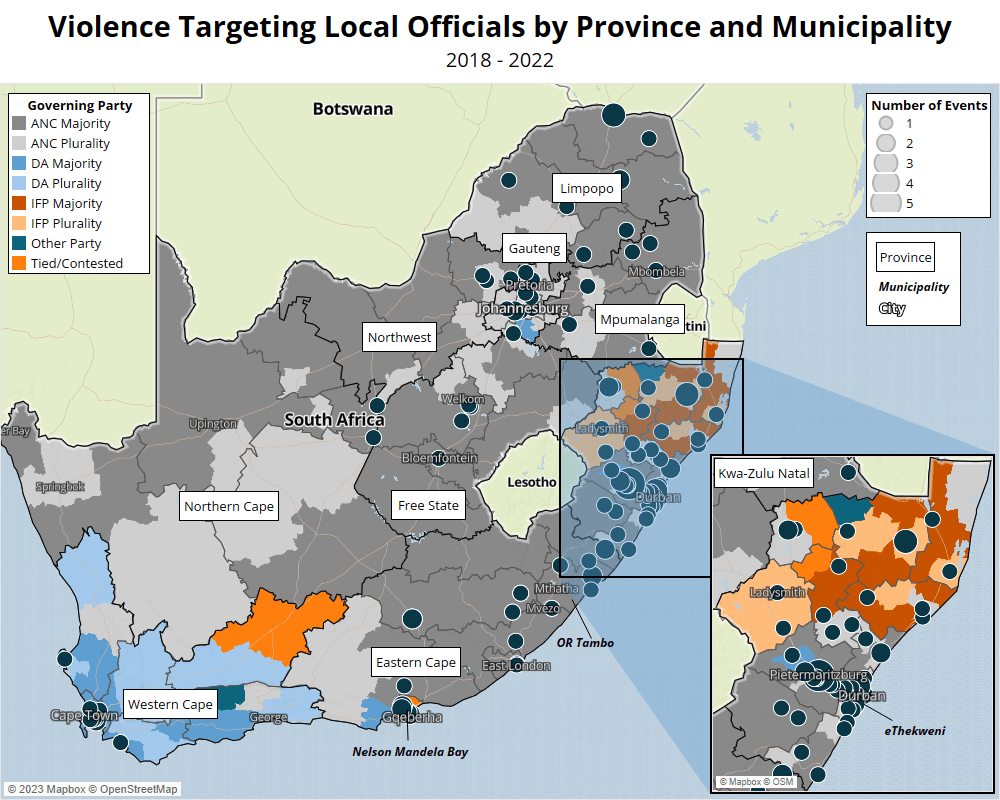

While contestation for power takes place in South Africa at all levels of government, 80% of violence targeting government representatives between 2018 and 2022 was directed against local officials. KwaZulu-Natal province has been the epicenter of this violence. Amidst bleak economic conditions, the persistence of corruption, and the deterioration of support for the ruling ANC, violence targeting local officials is on the rise – and may continue to escalate.