Actor Profile:

Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS)

26 July 2023

Introduction

Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) is an Islamist political and militant group mainly operating in Syria’s Greater Idleb area, which includes parts of Aleppo’s western countryside, the Lattakia mountains, and al-Ghab Plain in northwestern Hama. HTS leadership was historically composed of both Syrian and foreign Islamists, with links to the Islamic State and al-Qaeda. However, the group’s current identity is largely Syrian Islamist, reflecting a pragmatic shift in its strategic goals. HTS has rebranded itself from a former transnational Salafi-Jihadi group to a more localized Islamist group that at times targets and clashes with other radical Islamist groups such as the Islamic State and the al-Qaeda-affiliated Hurras-al-Din. With this change, the group has increasingly sought to cultivate a more moderate public image.

HTS actively maintains an area of territorial control in northwest Syria. The group’s capacity to project territorial authority came to the fore in the aftermath of the 6 February earthquakes. HTS blocked the entry of foreign aid from regime-held areas, preferring to wait for aid via Turkey, in order to deprive the regime of any ability to demonstrate control in the region. This actor profile tracks recent patterns of HTS activity, with a specific focus on its interactions with regime forces, Islamist and Turkey-backed opposition factions, and civilian populations, while also exploring potential trajectories for the group into the future.

From Jabhat al-Nusra to HTS

The group’s pedigree includes more than a decade of mergers, splits, and rebranding efforts to distance itself from its more extreme ideological origins. Its predecessor, Jabhat al-Nusra (JaN), was formed in late 2011 by the Saudi-born Abu Muhammad al-Jawlani at the behest of then-Islamic State of Iraq (ISI) leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi. In its initial form, JaN brought together disparate Salafi jihadi groups in the region, with the goal of overthrowing the Syrian regime and creating an Islamic state. Early JaN membership also included those recruited through Islamic State and al-Qaeda networks in Syria, ideological supporters, and hardline Islamist prisoners released by the regime of Bashar al-Assad early in the Syrian conflict.1Jennifer Cafarella, ‘Jabhat Al-Nusra in Syria: An Islamic Emirate for Al-Qaeda,’ The Institute for the Study of War, December 2014

In December 2012, the United States designated JaN a terrorist organization, with the United Nations Security Council and other Western governments following suit in the following months.2Press Center, “Terrorist Designations of the al-Nusrah Front as an Alias for al-Qa’ida in Iraq,” United States Department of State, 11 December 2012; Staff Writer, ‘UN Blacklists Syria’s Al-Nusra Front,’ Aljazeera, 31 May 2013 JaN quickly rose to prominence with early and effective battle successes against Syrian regime forces. This momentum led al-Baghdadi to announce the expansion of ISI into Syria with the creation of the Islamic State and the dissolution of JaN. Al-Jawlani resisted al-Baghdadi’s maneuvers in Syria and the two groups publicly severed ties, after which JaN launched a long and successful campaign to weaken Islamic State presence in northwest Syria.3Aaron Y. Zelin, ‘Jihadi ‘Counterterrorism:’ Hayat Tahrir al-Sham Versus the Islamic State,’ CTC Sentinel, Volume 16, Issue 2, February 2023

In July 2016, JaN also split with al-Qaeda and renamed itself Jabhat Fatah al-Sham (JFS). Two factors contributed to the decision to sever ties with al-Qaeda. First, the refusal of other opposition factions to unite under one military structure out of distrust of al-Jawlani and to avoid being branded terrorist organizations by the US.4JaN was excluded from the 2015 UN-sponsored negotiations between the Syrian regime and the opposition factions because of its designation as a terrorist organization, which threatened to weaken its position within the revolutionary milieu. Second, the targeting of JaN leaders following the expansion of the US-led Global Coalition Against Daesh air campaign against the Islamic State to Syria in September 2014.5Aron Lund, ‘What is the Khorasan Group and Why is the US Bombing it in Syria?,’ Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 23 September 2014 The break-up with al-Qaeda was rejected by a minority of JaN leaders and fighters who, in turn split, from JaN and reorganized under the banner of HAD.

In January 2017, JFS merged with four Salafi jihadist armed groups to form HTS, under the leadership of al-Jawlani. Over the course of 2017 and 2018, HTS launched several attacks against opposition groups, particularly Ahrar al-Sham, who had rejected HTS’s proposal to unite under a single militant organization. By January 2019, HTS had succeeded in subjugating most mainstream opposition factions and gradually asserted political and military control over the Greater Idleb area. Since then, and despite a significant retraction in territorial control, HTS has become the dominant non-state actor in the region.

Activity and Area of Operation

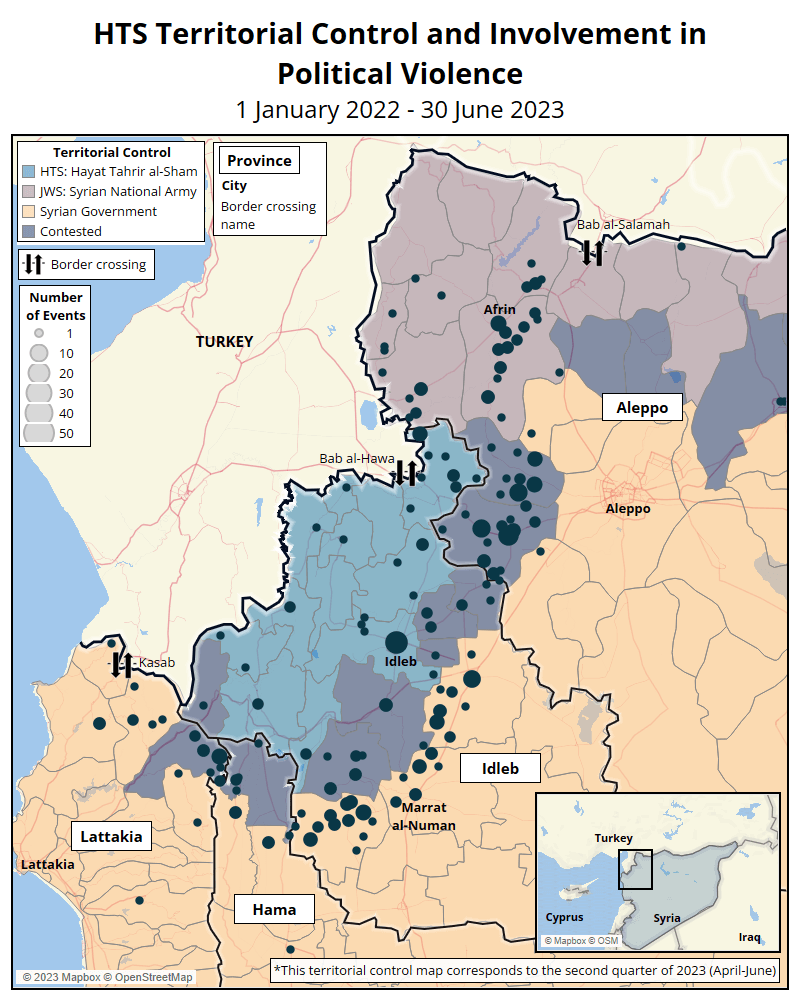

Since 2012, HTS and its predecessors have had an operational presence in several Syrian provinces, significantly in Aleppo, Hama, Lattakia, and Idleb. While at its zenith, in January 2017, HTS exerted territorial control over swaths of territory in northwest Syria; a sequence of Russian-backed offensives by the regime has since reduced HTS’s territorial reach. Currently, HTS controls what is considered to be the last stronghold of rebel factions in northwest Syria, which includes parts of Idleb, Aleppo, and the countryside of Hama, in addition to a small stretch in the northern countryside of Lattakia (see map below). It engages in a variety of activities, including armed clashes and shelling against regime forces along the frontlines, as well as acts of violence on civilians in areas under its control.

Increasing Confrontations with Syrian Regime Forces

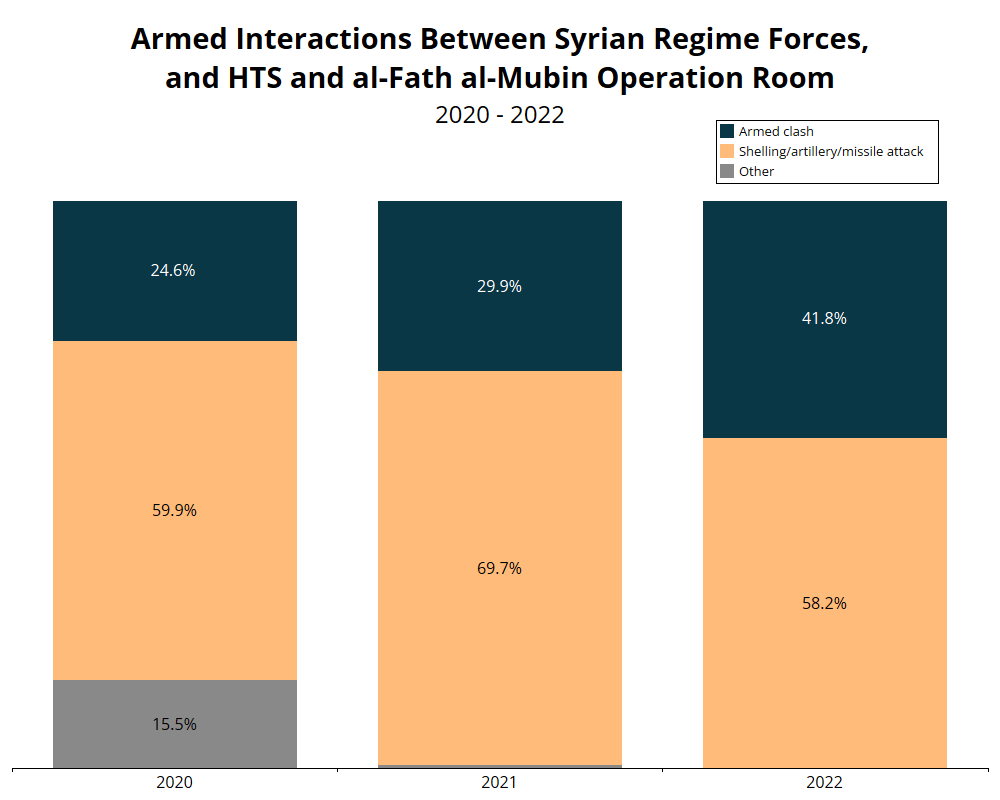

The frontline areas between regime forces and HTS in northwest Syria began to experience a slow decline in violence since the Turkish intervention in Idleb province and the Russian-Turkish truce that ended the regime offensives against rebel factions in March 2020. However, in 2022, two major changes in the levels and nature of violence occurred. First, HTS and its ally al-Fath al-Mubin Operation Room significantly increased their direct targeting of regime forces positions. Violent interactions between HTS and al-Fath al-Mubin Operation Room on one side, and regime forces on the other, nearly doubled from over 200 in 2021, to more than 400 in 2022 (see graph below). Second, while shelling continued to make up the majority of these interactions, there was a significant shift toward direct armed clashes. Armed clash events accounted for more than 40% of events in 2022 compared to less than 25% in 2020.

This change in the nature and levels of violence suggests that HTS has increasingly jockeyed for military advantage to demonstrate its continued value as an important military ally to Turkey in the face of the Syrian regime. Since mid-June 2022, Turkish and Syrian officials have held a series of meetings, and Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has expressed a willingness to hold talks with the Syrian regime.6Ece Toksabay and Huseyin Hayatsever, ‘Turkey Seeks a Trilateral Mechanism with Russia, Syria-Erdogan,’ Reuters, 15 December 2022 HTS may be attempting to force Turkey to take into account its interests in any negotiations with the Syrian regime while also showing the Syrian regime that it still has the military capabilities to fight it.

Infighting within the Islamist and Opposition Camps

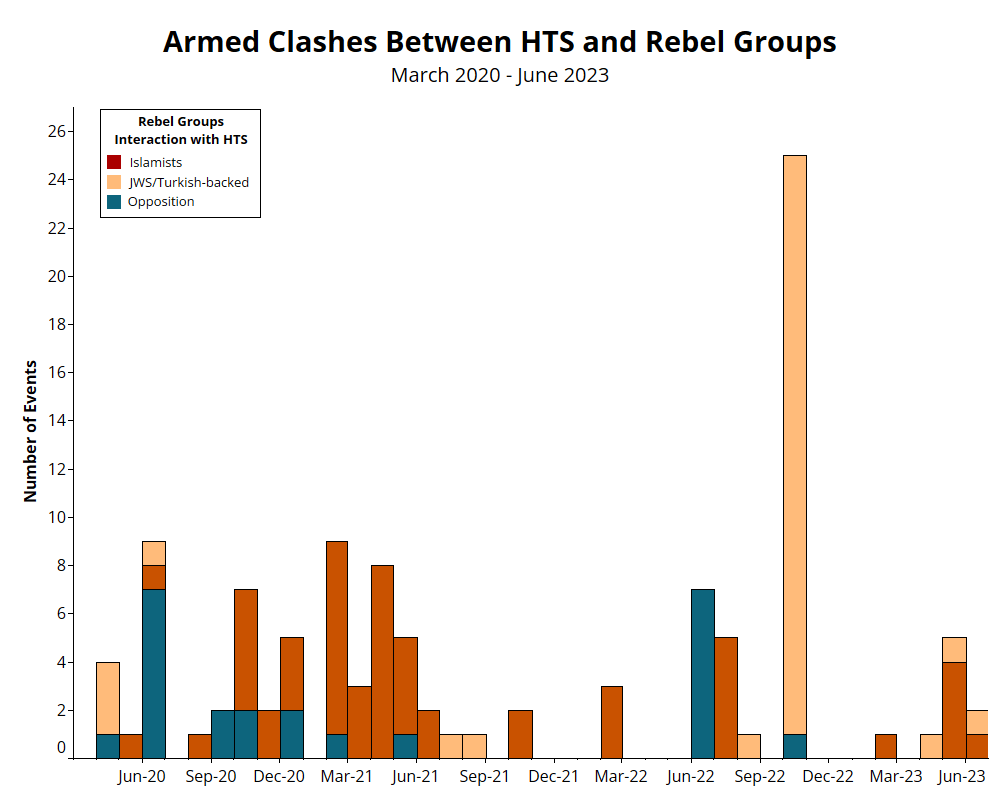

The 2020 Russian-Turkish truce enabled HTS not only to maintain its hegemony in Idleb province, but also to redirect some of its military efforts from targeting regime forces to absorbing or subduing the other Islamist groups (see graph below). Initially, its main targets were HAD and its Islamist allies, which had refused to merge with HTS, dissolve themselves, or leave Idleb. Since 2020, HTS has launched several attacks on HAD. In addition to clashes, HTS conducted several arrest campaigns against HAD commanders and members in Idleb province. Between December 2020 and February 2022, HTS detained at least 10 HAD leaders and commanders and dozens of fighters in Idleb and Aleppo provinces. It is also believed that HTS provided intelligence that led to the killing of two HAD leaders in an airstrike by the US-led Coalition Against Daesh in Idleb province on 20 September 2021.7Al-Monitor Staff, ‘US Drone Strike Kills Two Suspected al-Qaeda Officials in Idlib,’ Al-Monitor, 16 October 2020 HTS attacks and detention campaigns have been greatly detrimental to HAD, leaving it with what has been described as a “residual presence” in Idleb province.8UN Security Council, ‘Twenty-ninth report of the Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team submitted pursuant to resolution 2368 (2017)2368 (2017)2368 (2017)2368 (2017)2368 (2017)2368 (2017)2368 (2017)2368 (2017)2368 (2017)2368 (2017)2368 (2017) concerning ISIL (Da’esh), Al-Qaida and associated individuals and entities, S/2022/83’, 3 February 2022, p.12

While HTS actively sought to absorb or eliminate its Islamist rivals, until recently, it maintained good relations with rebel factions associated with the National Liberation Front (JTW) and Syrian National Army (JWS), formerly known as the Free Syrian Army, who still have military presence in Idleb. As such, ACLED records fewer than 10 political violence events between HTS and JWS in 2020 and 2021. This was the result of a strategic decision, partly due to the desire of HTS to maintain a relationship of patronage it had established with Turkey following the Russian-Turkish truce and on whom its hegemony in Idleb depends.9Jerome Devron and Patrick Haenni, ‘How global Jihad relocalises and where it leads : the case of HTS, the former AQ franchise in Syria,’ Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies Research Paper No. RSCAS 2021/08, January 2021

However, these relations changed in October 2022, when JWS factions and HTS engaged in full-fledged military confrontations. These confrontations arose when the latter took sides in clashes between different JWS factions. HTS supported the al-Hamzah Division and the Sultan Suleiman Shah Brigade in their clashes with the Third Corps (consisting mainly of Jaish al-Islam and the Levant Front), in the Afrin region of Aleppo province. The clashes broke out after the Third Corps factions launched several attacks on al-Hamzah Division in al-Bab city in retaliation for members of al-Hamzah Division killing a local activist and his wife. HTS had a surprisingly swift victory, defeating and expelling the Third Corps from Afrin city. After HTS took over control, an agreement, mediated by Turkey, was reached, stipulating an HTS withdrawal from Afrin city and the Third Corps confining its activities to the military sphere. In addition, the agreement provided for a power-sharing arrangement that allowed the HTS-backed Syrian Salvation Government to take part in the governance of rebel-held areas in the city.10Adnan al-Imam and Adnan Ahmed, ‘Submission to Tahrir al-Sham…an initial Agreement with the National Army (Jaysh al-Watany) on a joint Administration of Northern Syria,’ Al Araby Al Jadid, 16 October 2022

The intervention in Afrin was part of HTS’ larger effort to expand its control into opposition-controlled areas in northern Aleppo, increase its financial gains through the control of crossings with regime and QSD- controlled areas, and ensure its military advantage over JWS. Furthermore, HTS’ swift victory over the Third Corps demonstrates the value of HTS as a military ally to Turkey amid the continued failure of JWS to maintain stability in the region due to the long-standing tensions and conflicts among its factions.

Desired Legitimacy Threatened by Violence Against Civilians

Since breaking ties with al-Qaeda in 2016 and defeating Ahrar al-Sham in 2017, HTS has not only sought to consolidate its military control over the Greater Idleb area, but also assert itself as the sole legitimate political authority in its areas of control. Unlike transnational jihadist groups such as al-Qaeda, HTS has made efforts to gain legitimacy in the eyes of local populations by presenting itself as an intrinsic part of the Syrian revolution and projecting a local focus.11Christopher Solomon, ‘HTS: Evolution of a Jihadi Group’, Wilson Center, 13 July 2022 The formation in 2017 of the Syrian Salvation Government (SSG), a body made up of independent and HTS-linked technocrats, was one such effort. Since then, SGG has functioned as the HTS’s governance wing, through which the group has embedded itself within local communities to gain political, social, and economic legitimacy. Through the SSG, HTS administers various welfare services, delivers essential goods, and runs food aid programs. It also has a monopoly on the economy through control of al-Sham Bank and the oil sector through Watad Company.12Nisreen Al- Zaraee and Karam Shaam, ‘The Economics of Hayat Tahrir al-Sham’, The Middle East Institute, 21 June 2021 Moreover, SSG also controls and issues civil documentation for more than 3 million civilians, two-thirds of which are internally displaced people.13Mahmoud Hamza, ‘Idlib’s de facto authorities issue new ID cards: A ‘temporary solution’ or more chaos?’, Syria Direct, 22 September 2022 Subsequently, SSG has established itself as the de facto administrative authority in the territories under its purview.

In addition, HTS controls the Bab al-Hawa border crossing with Turkey, through which flows the humanitarian aid on which 90% of the four million people living in northwest Syria depend. However, the functioning of this border crossing is subject to the UN Security Council’s decision.14UN News, ‘Security Council unanimously agrees to extend Syria cross-border aid lifeline’ United Nations, 2 January 2023 In addition to Bab al-Hawa, HTS also controls the Ghazawiyah crossing (between Darret Izza and Afrin) with JWS-controlled areas and the informal Dorriyeh crossing with Turkey, through which people and goods are smuggled. HTS has made several unsuccessful attempts to reopen crossings with the regime, as they have been met with protests from residents and resistance from Turkish forces. HTS’s interest in reopening crossings with regime-held areas demonstrates the group’s pragmatism that has allowed it to succeed against other more mainstream opposition factions.15Charles Lister, ‘Pragmatic jihadist or opportunist warlord? HTS’s Jolani expands his rule in northern Syria,’ Middle East Institute, 13 October 2022 Equally, though, HTS prevented foreign aid from regime-held areas following the earthquakes in February, instead only accepting aid through Turkey.16Timour Azhari and Maya Gebeily, ‘Syria quake aid held up by hardline group, U.N. says’, Reuters, 12 February 2023

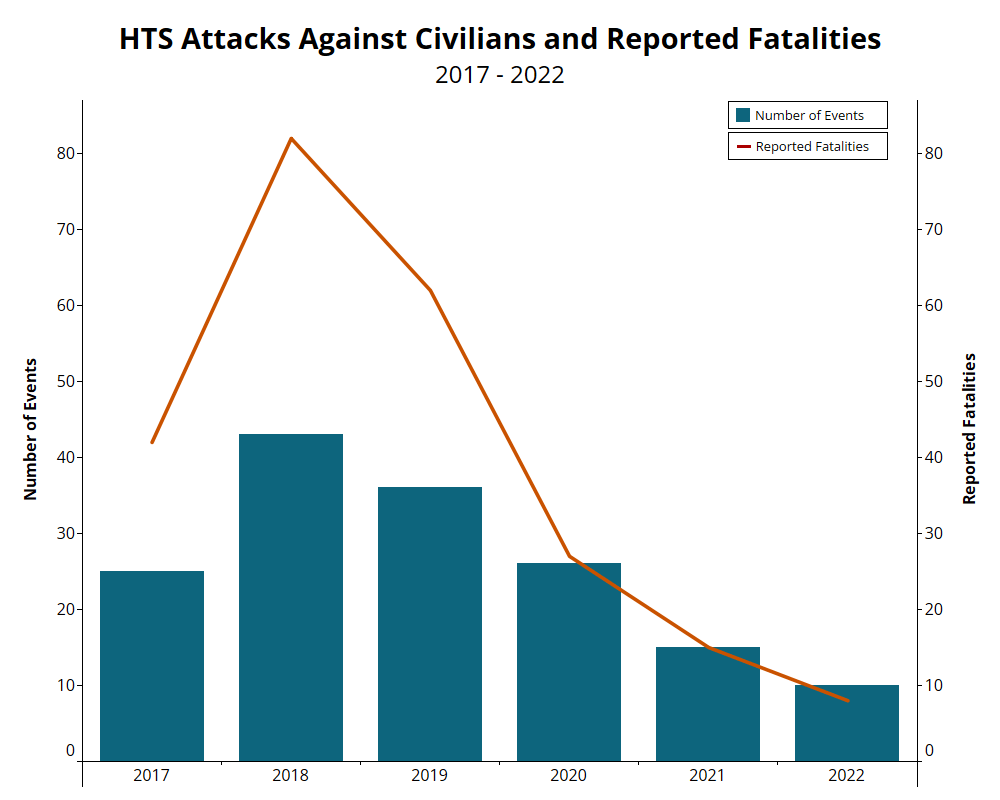

HTS’s efforts to project an image of legitimacy have been tainted by allegations of persistent human rights abuses. Between 2020 and 2022, HTS militants have reportedly continued to engage in violence against civilians, although these trends have largely declined compared to the pre-2020 period (see graph below). During this period, ACLED records nearly 60 reported attacks on civilians attributed to HTS, resulting in the deaths of at least 54 civilians. Among those reportedly killed, 19 were prisoners who were either executed by HTS or died while being tortured in HTS-run prisons. The charges against detainees range from criticizing HTS to affiliation with other factions or regime and Russian forces, to collaboration with the Global Coalition Against Daesh.17Syrian Network for Human Rights, ‘The Most Notable Hay’at Tahrir al Sham Violations Since the Establishment of Jabhat al Nusra to date,’ 31 January 2022 Arbitrary killings and unlawful detentions of civilians have resulted in widespread discontent among local populations, leading to protests in many parts of Idleb. Between 2020 and 2022, ACLED records over 15 demonstrations in Idleb calling for the release of detainees from HTS prisons.

What Future for HTS in Northwest Syria?

The ongoing Turkish rapprochement with the regime will likely have significant effects on the dynamics of political violence in northwest Syria. On 28 December 2022, Turkish and Syrian defense ministers held their first ministerial-level meeting in Moscow to discuss the conflict. Since then, HTS and al-Fath al-Mubin Operation Room have carried out more than 80 direct attacks against regime positions in Idleb and Aleppo provinces, and for the first time, more than half of reported incidents took the form of armed clashes. HTS and al-Fath al-Mubin Operation Room are expected to step up their infiltration and sniper attacks against the regime forces in order to push for HTS inclusion in any future settlement or agreement in northwest Syria. Through this change in tactics, HTS aims to demonstrate its capability to enter into war with the regime should the current rapprochement efforts fail or exclude HTS, or should Turkey withdraw its forces from Syria.

HTS remains the most powerful anti-government armed group in northwest Syria. This was most recently demonstrated by its continued willingness to fight the regime, its swift victory in Afrin, and its ability to control the flow of aid in its areas of operation. Yet, despite significant success over the past three years, HTS nevertheless faces many challenges to its military and political projects. In addition to the constant threat of an intensified confrontation with the Syrian regime, HTS continues to grapple with the delicate and unstable relations of patronage it formed with Turkey and the refusal of Western countries to delist the group and engage directly with its leadership. Moreover, the stability of HTS governance projects in northwest Syria continue to be threatened by rising public anger and protests sparked by the group’s arrest campaigns against civilians and members of other Islamist factions. These challenges will likely force HTS to transform, further shifting from its roots in the jihadi movement toward a stronger opening to mainstream revolutionary factions and greater alignment with Turkish and Western interests.