Fact Sheet: Military Coup in Niger

Published: 3 August 2023

Key Trends

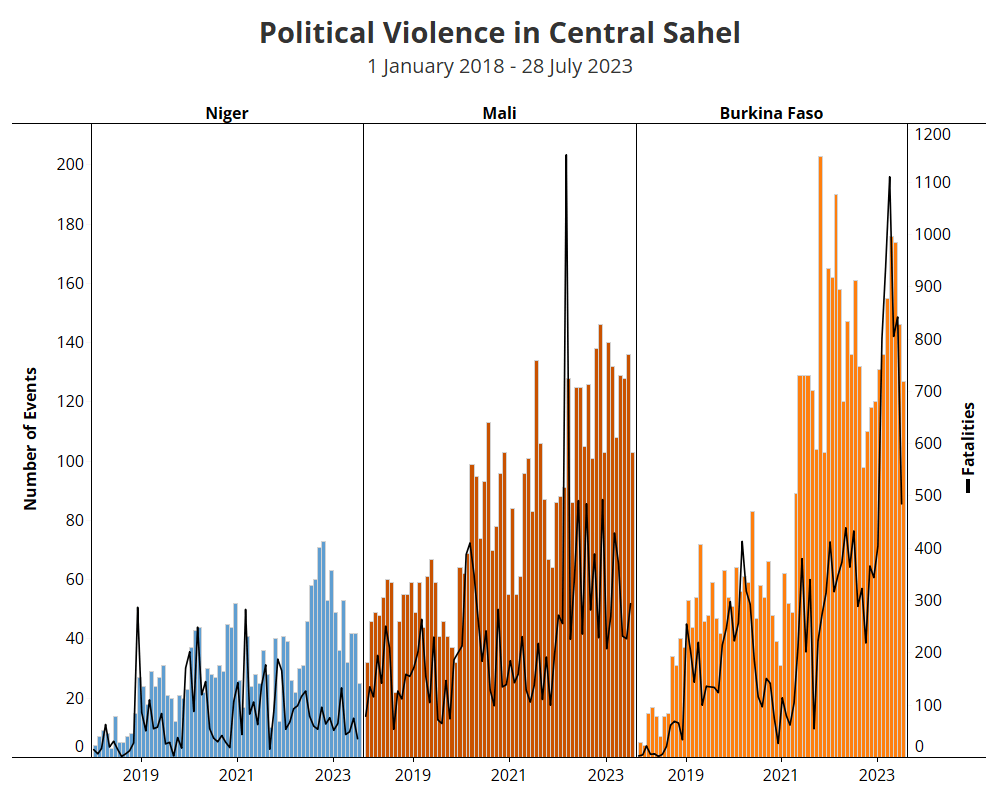

- Niger has experienced continuous growth in jihadist activity since 2018, with a record year for violence in 2021 measured by fatalities

- While the number of political violence incidents increased further in 2022, the lethality of the violence has steadily declined, with a significant overall decrease in fatalities last year

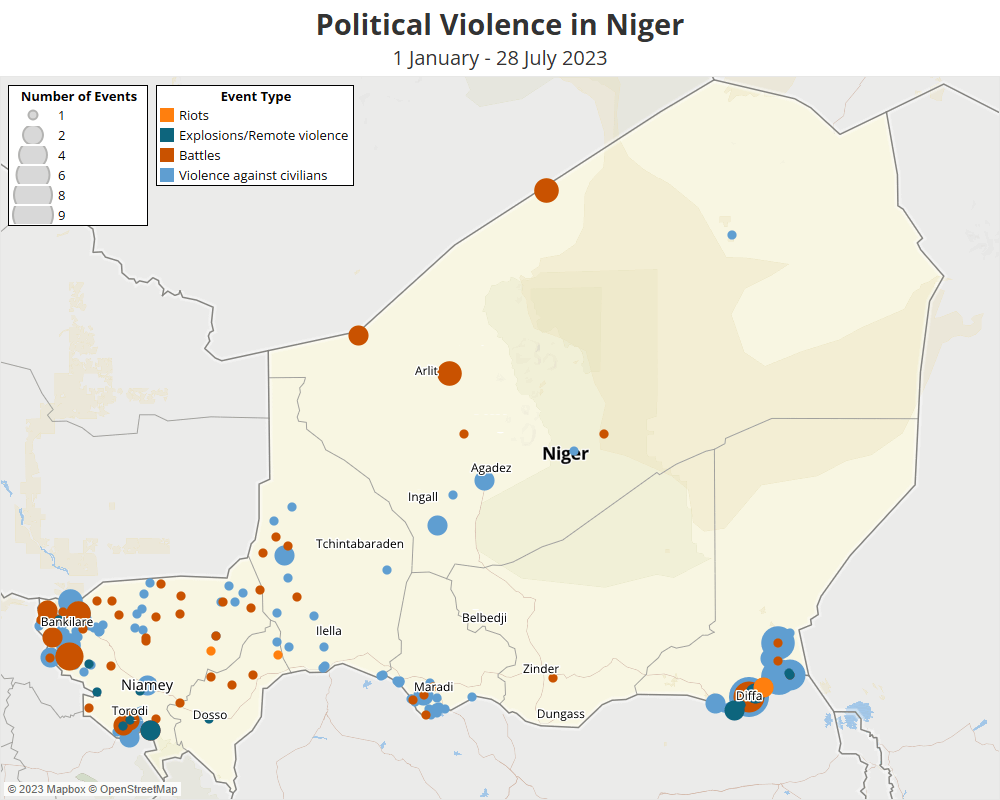

- In the first six months of 2023, political violence decreased by an estimated 39% when compared to the previous six-month period from July to December 2022

- Attacks on civilians decreased by 49%, and resulting fatalities decreased by 16%

- Operations by the Nigerien security forces increased by 32%, however, as part of a continuous effort to counter insecurity

- Cases of looting and property destruction were the most common type of incident during this period, suggesting that militant groups like IS Sahel and JNIM increasingly see Niger as a key target for resource extraction

- The western Tillaberi region is the most affected by conflict, although there has been a notable geographic shift from the north to the west

Observations principales

- Depuis 2018, le Niger a connu une croissance ininterrompue des activités djihadistes sur son territoire, 2021 constituant une année de violence sans précédent en termes de décès rapportés

- Alors que le nombre de cas de violence politique a continué d’augmenter en 2022, les violences sont de moins en moins meurtrières, avec une baisse globale significative du nombre de décès rapportés l’année dernière

- Au cours des six premiers mois de 2023, les violences politiques ont diminué d’environ 39 % par rapport au semestre précédent (juillet – décembre 2022)

- Les attaques visant des civils ont diminué de 49%, et les décès résultant de ces attaques ont diminué de 16%

- Le nombre d’opérations menées par les forces de sécurité nigériennes a toutefois augmenté de 32%, dans le cadre d’un effort soutenu de lutte contre l’insécurité

- Les pillages et les destructions de biens ont été le type d’incident le plus fréquent au cours de cette période, signe que des groupes militants comme l’EIGS et le GSIM considèrent de plus en plus le Niger comme une cible de choix pour la captation de ressources

- La région occidentale de Tillabéri demeure la plus touchée par les conflits, bien que ceux-ci aient opéré un glissement géographique notable du nord vers l’ouest

Overview

On 26 July 2023, the Presidential Guard in Niger launched a coup and detained President Mohamed Bazoum and his family. Senior officers from various branches of the defense and security forces (FDS) formed a junta, named the National Council for the Safeguarding of the Homeland (CNSP), and announced the seizure of power on a televised broadcast. Public response varied, with initial demonstrations in support of Bazoum being dispersed by mutinous soldiers, followed by subsequent demonstrations in support of the CNSP. By 27 July, the Nigerien Armed Forces joined the CNSP, citing their intent to avoid lethal confrontation and to safeguard the president and his family.

The coup has largely been condemned internationally, including by key stakeholders like the United States, France, the European Union, and ECOWAS. During a summit in Nigeria’s capital Abuja, ECOWAS considered military intervention, and threatened sanctions to pressure the junta to reinstate Bazoum by giving a one-week ultimatum. The West African Economic and Monetary Union (UEMOA) imposed immediate sanctions and froze Nigerien state assets. Burkina Faso, Guinea, and Mali have declared their support for the Nigerien junta and expressed their refusal to apply any sanctions imposed on Niger. Burkina Faso and Mali further warned in a joint statement that any military intervention in Niger was a declaration of war against the two countries. The reactions in support of Niger from the junta-led states has set the stage for a deeper divide and potential break-up of the West African bloc.

The coup’s aftermath brings a high potential for domestic unrest and regional conflict, a surge in militant activities, democratic backsliding and restriction of civil liberties, and severe socio-economic consequences due to sanctions. Furthermore, the military junta has not consolidated its power grab and faces strong opposition by many international stakeholders. Bazoum not only enjoys support from the international community but also from a large segment of the population across Niger, with signs of supporters counter-mobilizing for mass demonstrations against the junta.

Underlying Discontent and Palace Politics

Niger represents the last of the three central Sahel states to succumb to a military coup, after Mali in 2020 and 2021, and two coups in Burkina Faso in 2022. While some interpret this event through the context of Russia’s increasing influence or its alignment with Western military training initiatives, the primary catalysts were essentially domestic in nature. The leader of the coup, General Abdourahamane Tchiani, was rumored to be on the verge of losing his position as head of the Presidential Guard – a role in which he had defended the regime against numerous attempted coups during the tenures of both former President Mahamadou Issoufou and his successor Bazoum. It is possible that growing discontent within the FDS had intensified over the years under the rule of Issoufou and his successor Bazoum. This underlying dissatisfaction may have set the stage for the recent military coup, given the swift alignment of other senior military officers. Past coup attempts further underscore a fragile balance on which the regime had to perch and a threat that Bazoum may have underestimated. The decision by senior officers from various branches to join the junta does not necessarily mean unequivocal support for the coup. Instead, it may reflect a strategic move to manage the unfolding crisis, while seizing the opportunity to dismantle the entrenched political system established by the ruling party PNDS under the leadership of Issoufou and Bazoum.

Amid growing anti-French sentiments in neighboring Mali and Burkina Faso, as well as within Niger, the country paradoxically found itself increasingly set apart in the central Sahel, representing France’s last ally and counter-terrorism hub. While Bazoum’s rhetoric was candid, it was often perceived as publicly antagonistic and patronizing towards his Sahelian counterparts, whether or not his points were valid. This particularly applies to his critiques of Mali’s decision to partner with the Russian private military company Wagner Group and Burkina Faso’s strategy to mobilize self-defense militias – policies that have seemingly exacerbated violence and security issues within the two neighboring countries. Moreover, as the supreme commander of Niger’s armed forces, Bazoum’s recent interview, in which he suggested that militants were “stronger and more battle-hardened” than the region’s armies, was likely a misstep. This comment may have been seen as demoralizing, striking a nerve within the military and contributing to rising tensions in the lead-up to the coup.

Violence and Conflict Trends

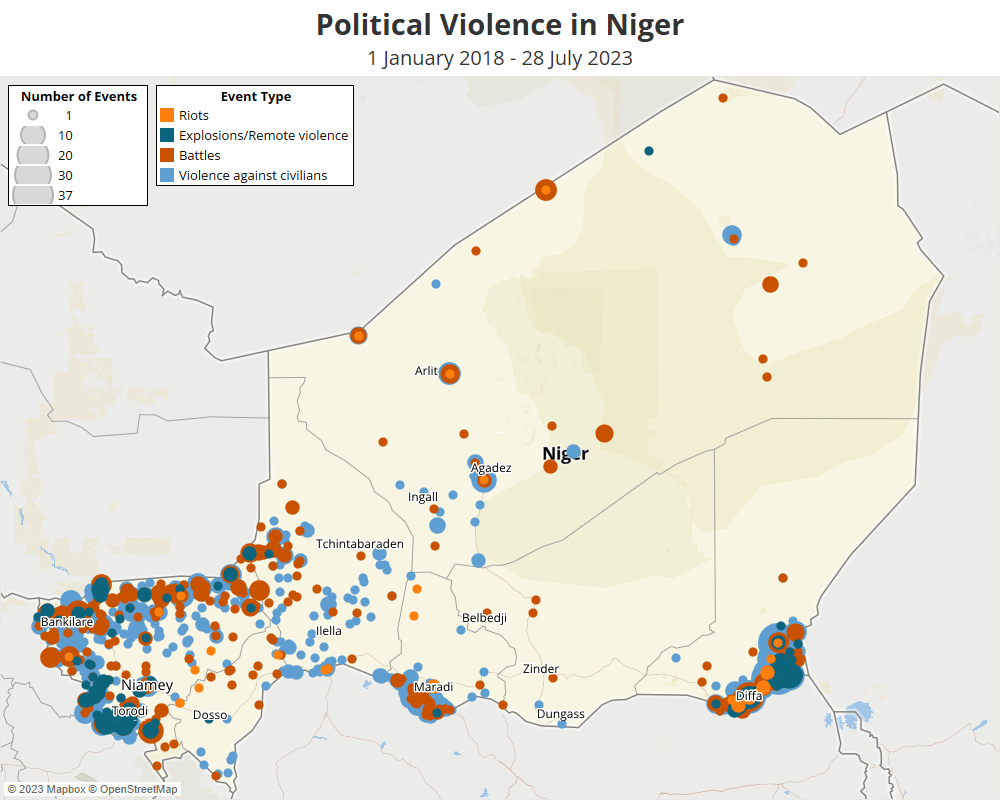

Niger confronts an array of security challenges: in the west, it faces the Sahelian insurgency driven by IS Sahel and the al-Qaeda-affiliated JNIM, while the southeastern Diffa region is affected by the ISWAP and Boko Haram insurgency. The central Tahoua region is seeing a mixture of IS Sahel militancy and banditry. In Maradi, along the southern border with Nigeria, organized bandit gangs are also highly active. The Agadez region, rich in gold and smuggling routes that stretch along the border with Libya, Algeria, and Chad, has additionally attracted a plethora of armed groups, among them Chadian and Sudanese rebels, drug traffickers, and organized criminal gangs, all contributing to widespread rural banditry (see map below).

The Tillaberi region remains most affected by conflict, although there is a notable geographic shift from the northern to the western parts of the region. This shift in violent activity may be attributed to several converging factors. Notably, IS Sahel, the most active armed actor in both the country and the Tillaberi region, refocused its efforts on the Malian side of the border in early 2022. This strategic redirection coincided with France’s withdrawal of forces from Mali and the subsequent reconfiguration of its mission to Niger, where operations were primarily concentrated in northern Tillaberi. IS Sahel and JNIM also engage in simultaneous campaigns in neighboring Burkina Faso, with the border areas in western Tillaberi being used as staging ground. Furthermore, Nigerien authorities have been making concerted efforts to resolve long-standing intercommunal conflicts in Ouallam and Banibangou, the departments previously most affected by violence. The combination of these factors likely contributed to the observed shift in armed engagements.

Despite these challenges, Niger has statistically fared better than its neighbors in terms of violence and conflict. The military junta cited the “continually deteriorating security situation” as a core justification for the coup. The years of 2019 and 2020, during Issoufou’s reign, were particularly devastating for the Nigerien FDS as they suffered heavy losses due to a series of mass-casualty attacks perpetrated by IS Sahel. In 2021, Niger experienced a record year of conflict coinciding with its first democratic transition when Bazoum succeeded Issoufou. Ever since, Niger continues to see high numbers of conflict incidents, although levels of lethal violence are in steady decline, and significantly reduced in comparison to Mali and Burkina Faso (see graph below).

Outlook

As the dust from the coup begins to settle, Niger stands at a crossroads. The success of the junta in maintaining power and building legitimacy are not guaranteed, with significant opposition domestically and internationally. The junta is yet to consolidate its position and the situation is far from stabilized. Persistent support for Bazoum brings the potential for continued unrest, mass demonstrations against the junta, and violent contestation among pro-junta and pro-regime camps, adding additional layers of uncertainty. The potential fallout of this instability may affect the entire Sahel region, exacerbating existing security challenges and possibly giving rise to new threats both domestically and regionally due to the ramifications of the current crisis. Ongoing insurgencies and armed groups like JNIM, IS Sahel, ISWAP, and Boko Haram (JAS) may exploit and profit from such instability and discord, leading to escalating levels of violence.

The consolidation of power by the Nigerien junta would represent the further spread of democratic backsliding in the Sahel. Should this occur, all central Sahelian states would be effectively ruled by military juntas, marking the end of democracy in the subregion for the time being. Niger will likely face similar consequences as have already been observed in neighboring Mali and Burkina Faso, where the ascension of military governments led to the erosion of civil liberties and fundamental rights, including freedom of press and expression. Furthermore, all three countries have so far failed to suppress a growing regional insurgency expanding across West Africa. Niger is also at risk of severe socio-economic repercussions due to anticipated sanctions and suspension of development and budgetary aid. These pressures are likely to further strain Niger’s already fragile economy.

Aperçu de la situation

Le 26 juillet 2023, la garde présidentielle du Niger a lancé un coup d’État et fait arrêter le président Mohamed Bazoum et certains membres de sa famille. Des officiers de haut rang issus de plusieurs branches des Forces de défense et de sécurité (FDS) ont formé une junte, nommée Conseil national pour la sauvegarde de la patrie (CNSP), et ont annoncé leur prise de pouvoir lors d’une allocution télévisée.1Air Info, ‘Niger : Qui sont les 10 officiers auteurs de la déclaration du putsch ?,’ 28 juillet 2023 Les réactions de la société civile ont été contrastées, les premières manifestations de soutien à Bazoum ayant été dispersées par des soldats acquis à la cause des putschistes, tandis que d’autres manifestations ont suivi, cette fois en faveur du CNSP. Le 27 juillet, les forces armées nigériennes ont rallié le CNSP, déclarant vouloir éviter une confrontation meurtrière et protéger le président et sa famille.

Le coup d’État a été amplement condamné par la communauté internationale, notamment par des acteurs majeurs tels que les États-Unis,2France24, ‘Blinken says ousted Niger president has ‘unflagging’ US support after coup’, 29 juillet 2023; VOA, ‘US Threatens to Pull All Aid for Niger, 29 juillet 2023 la France,3Radio France, ‘Coup d’Etat au Niger : la France suspend “avec effet immédiat” ses actions d’aide au développement au pays,’ 29 juillet 2023 l’Union européenne4BBC, ‘Niger coup: EU suspends security cooperation and budgetary aid,’ 29 juillet 2023 et la CEDEAO. Réunie en sommet à Abuja, la capitale du Nigeria, la CEDEAO a donné un ultimatum d’une semaine à la junte, évoquant la possibilité d’une intervention militaire et menaçant de prendre des sanctions afin qu’elle rétablisse Bazoum.5Reuters, ‘West African leaders threaten sanctions, force against Niger coup leaders,’ 30 juillet 2023 L’Union économique et monétaire ouest-africaine (UEMOA) a, elle, immédiatement imposé des sanctions et gelé les avoirs de l’État nigérien.6BNN, ‘Rigorous Sanctions Imposed on Niger by West African Economic and Monetary Union,’ 30 juillet 2023 Le Burkina Faso, la Guinée et le Mali ont, en réaction, exprimé leur soutien à la junte nigérienne et signalé leur refus d’appliquer les sanctions imposées au Niger. Dans une déclaration commune, le Burkina Faso et le Mali ont, en outre, mis en garde contre toute intervention militaire au Niger, indiquant qu’ils la considèreraient comme une déclaration de guerre contre leurs deux pays. Les réactions de soutien au Niger de la part d’autres États de la région dirigés par des juntes semblent avoir créé les conditions d’une division plus profonde et d’un éclatement potentiel du bloc ouest-africain.

Le coup d’État risque fortement de déstabiliser le pays et la région, de favoriser une recrudescence des activités des groupes militants, un recul de la démocratie ainsi qu’une restriction des libertés civiles, et d’entraîner de graves conséquences socio-économiques du fait de l’introduction de sanctions. De plus, la junte militaire n’a pas totalement affermi son emprise sur le pouvoir et fait face à une forte opposition de la part de nombreux acteurs internationaux. Mohamed Bazoum dispose non seulement du soutien d’une grande partie de la communauté internationale, mais aussi de celui d’un large pan de la population nigérienne, qui semble vouloir mobiliser ses partisans en vue de manifestations de masse contre la junte.

Grogne latente et intrigues de palais

Le Niger est le dernier des trois États du Sahel central à connaître un coup d’État militaire, après le Mali en 2020 et 2021, et deux coups d’État au Burkina Faso en 2022. Si certains analysent cet événement dans le contexte de l’influence croissante de la Russie, ou de son calquage des initiatives occidentales de formation militaire dans la région, ses principaux catalyseurs sont surtout d’ordre national. Le chef des putschistes, le général Abdourahamane Tchiani était, d’après les rumeurs, sur le point d’être limogé de son poste de chef de la garde présidentielle,7Jeune Afrique, ‘Au Niger, tentative de coup d’État contre Mohamed Bazoum,’ 26 juillet 2023 un rôle dans lequel il avait défendu le régime contre de nombreuses tentatives de coup d’État pendant les mandats de l’ancien président, Mahamadou Issoufou, et de son successeur, Mohamed Bazoum. Il est probable que le ressentiment au sein des FDS se soit intensifié au fil des années, d’abord sous le régime d’Issoufou, puis sous celui de son successeur. Ce sentiment de mécontentement latent pourrait avoir ouvert la voie au récent coup d’État militaire, étant donné le ralliement rapide d’autres hauts gradés de l’armée. Les précédentes tentatives de coup d’État montrent, de plus, que l’équilibre du régime était précaire et que Bazoum avait peut-être sous-estimé la menace qui pesait sur lui. Néanmoins, la décision d’officiers de haut rang appartenant à différentes branches de l’armée de rejoindre la junte ne signifie pas nécessairement un soutien sans équivoque aux putschistes. Elle pourrait, au contraire, refléter un choix stratégique visant à maîtriser la crise en cours, tout en tirant parti de l’occasion pour démanteler le système politique établi par le parti au pouvoir, le PNDS, sous la direction d’ Issoufou et de Bazoum.

Dans un contexte de montée des sentiments anti-français au Mali et au Burkina Faso voisins, ainsi qu’au sein de la société nigérienne, le pays s’était paradoxalement retrouvé dans une posture de plus en plus singulière dans le Sahel central, puisqu’il représentait le dernier allié de la France et la plaque tournante du dispositif de lutte de celle-ci contre le terrorisme dans la région. Si la communication de Mohamed Bazoum était directe, elle a souvent été perçue comme ouvertement contradictoire et condescendante vis-à-vis de celle de ses homologues sahéliens, que les positions ainsi exprimées aient été fondées ou non. Cela vaut tout particulièrement pour ses critiques quant à la décision du Mali de s’associer à la société militaire privée russe Wagner et à la stratégie du Burkina Faso de faire appel à des milices d’autodéfense ; des choix qui ont, semble-t-il, exacerbé les violences et les problèmes de sécurité dans les deux pays. Par ailleurs, la récente interview de Bazoum, dans laquelle il a suggéré, bien que revêtant le rôle de commandant suprême des forces armées nigériennes, que les groupes militants étaient « plus forts et plus aguerris » que les armées de la région, a probablement constitué une faute. Ce commentaire a pu être perçu comme démoralisant, heurtant ainsi la sensibilité des militaires et alimentant davantage les tensions qui ont précédé le coup d’État.

Évolution des violences et des affrontements

Le Niger est confronté à une multitude de défis sécuritaires : à l’ouest, il fait face à l’insurrection sahélienne menée par l’EIGS et le GSIM (affilié à Al-Qaïda), tandis que la région de Diffa, au sud-est, demeure en proie aux activités de l’EIAO et aux insurrections de Boko Haram (JAS). La région centrale de Tahoua est, de plus, le théâtre d’un mélange de militantisme de l’EIGS et de banditisme. À Maradi, le long de la frontière sud avec le Nigéria, des groupes organisés de bandits sont également très actifs. La région d’Agadez, riche en or et traversée par de multiples voies de contrebande qui s’étendent le long de la frontière avec la Libye, l’Algérie et le Tchad, continue en outre d’attirer une pléthore de groupes armés, parmi lesquels des rebelles tchadiens et soudanais, des trafiquants de drogue et des groupes criminels organisés, qui nourrissent chacun une forme de banditisme rural généralisé (voir la carte ci-dessous).