Political Succession and Intra-Party Divisions: Examining the Potential for Violence in Zimbabwe’s 2023 Elections

17 August 2023

Zimbabwe is holding a general election on 23 August, with a possible run-off election scheduled on 2 October if no presidential candidate reaches 50% in the first round. The contest mirrors that of 2018, as current President Emmerson Mnangagwa (hereafter referred to as EDM), who leads the ruling Zimbabwe African National Union – Patriotic Front (ZANU-PF) party, will run against the main opposition leader Nelson Chamisa of the Citizens Coalition for Change (CCC), formerly the Movement for Democratic Change (MDC), led by the late Morgan Tsvangirai.

This election comes during a sustained period of Zimbabwe’s political isolation from the West, continued sanctions from the United States, and a general sense of malaise among many in the population.1United States Department of the Treasury, ‘Treasury Takes Additional Actions in Zimbabwe,’ 12 December 2022; Joseph Cotteril and Kudzanai Musengi, ‘Zimbabwe election offers regime a last chance to end financial isolation,’ Financial Times, 20 July 2023 Zimbabweans have been contending with the directionless government under EDM since the ouster of long-time president and ‘father of the nation’ Robert Mugabe, who passed away in 2019 (removed from office in late 2017). Many Zimbabweans seek changes to existing policies and political practices, although the passing of the ‘Patriot Act’ by the Senate – which criminalizes “wilfully injuring the sovereignty and national interest of Zimbabwe” – is expected to further restrict freedom of expression.2Zimbabwe Situation, ‘Patriot Act Now Law with effect from Friday 14th July 2023,’ 17 July 2023; Human Rights Watch, ‘Zimbabwe: Repression, Violence Loom over August Election,’ 3 August 2023 The result of this election is very likely to be continued ZANU-PF rule, even if the win is close. Such a victory may be achieved through efforts to tilt the odds in ZANU-PF’s favor via long-practiced methods like altering electoral rolls, blocking potential candidates from registering, and preventing voting on election day.3Mail & Guardian, ‘Ghost voters haunt Zimbabwe elections,’ 12 August 2023; Nic Cheeseman and Brian Klaas, ‘How To Rig An Election,’ Yale University Press, 2018

This is the second election after the removal of former President Mugabe. The 2018 election at least had some novelty and aspirations for EDM to change course. The five years that followed eliminated those hopes. However, the central fact remains that ZANU-PF has control over the levers of power at all scales, undermining the independence of public and private media,4New Zimbabwe, ‘Zanu PF corrupt elite captures Zimbabwe’s private media — Coltart,’ 22 January 2023 the electoral commission,5Chris Murnozi, ‘Zimbabwe electoral appointments spark controversy ahead of 2023, Al Jazeera, 1 August 2022 and the judiciary.6Dewa Mavhinga, ‘Zimbabwe Constitutional Court May Lose its Independence,’ Human Rights Watch, 27 July 2017 Yet, the ruling party’s influence also extends to local government institutions,7http://www.scielo.org.za/scielo.php?script=sci_abstract&pid=S2077-49072019000100003 the economy,8Michelle Gavin, ‘New Report Shines Spotlight on Corruption in Zimbabwe, Council on Foreign Relations, 19 February 2021; Reuters, ‘Zimbabwe committed to $6 bln debt arrears clearance, president says,’ 23 February 2023 and the security sector.9Zimbabwe Situation, ‘Security sector intertwined with Zanu PF,’ 17 December 2017 Across Zimbabwe, members of the party’s youth wing are likewise encouraged to make trouble for local opposition (for example, the recent murder of a CCC supporter).10Voice of America, ‘Witnesses: Zimbabwe Ruling Party Followers Killed Opposition Supporter,’ 4 August 2023; An older report notes the prevalence of factional ZANU-PF youth militias circa 2010, although these more militant factions have not been present since, and instead more ‘street fighting’ and ‘mob violence’ is more prevalent. See, Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada, ‘Youth militia activities, including those of the National Youth Service (NYS) and of the Green Bombers; training programs and incidents of violence since February 2009; whether youth militia target supporters of the Movement for Democratic Change (MDC),’ 17 May 2011 In short, the opposition parties wish to make this an election about the misdirection of ZANU-PF governance and policies to correct the serious malaise in Zimbabwe, but at its core it remains a contest of who has power.

ZANU-PF’s Strict Enforcement of Party Loyalty

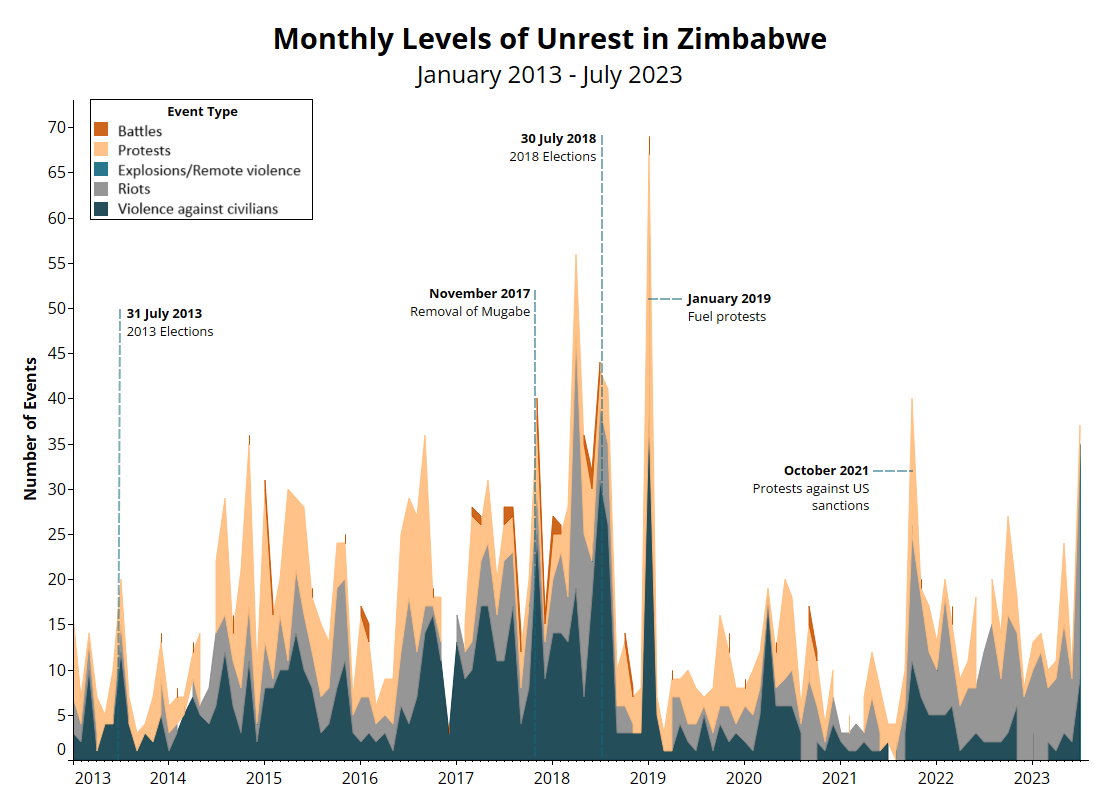

But will the election lead to more violence? Immediately preceding and during EDM’s tenure as president (EDM served for 50 years on Mugabe’s side before ousting him), violence and demonstrations peaked during the 2017 removal and 2018 election period. Subsequently, violence and demonstration levels have become substantially lower (see graph below). Elections do not generally lead to overall higher violence in Zimbabwe – violence accelerates most quickly when a run-off election is scheduled. The most common and extreme political violence in Zimbabwe has typically come from internal competition and political consolidation within ZANU-PF, not from the continued efforts to disable the opposition.

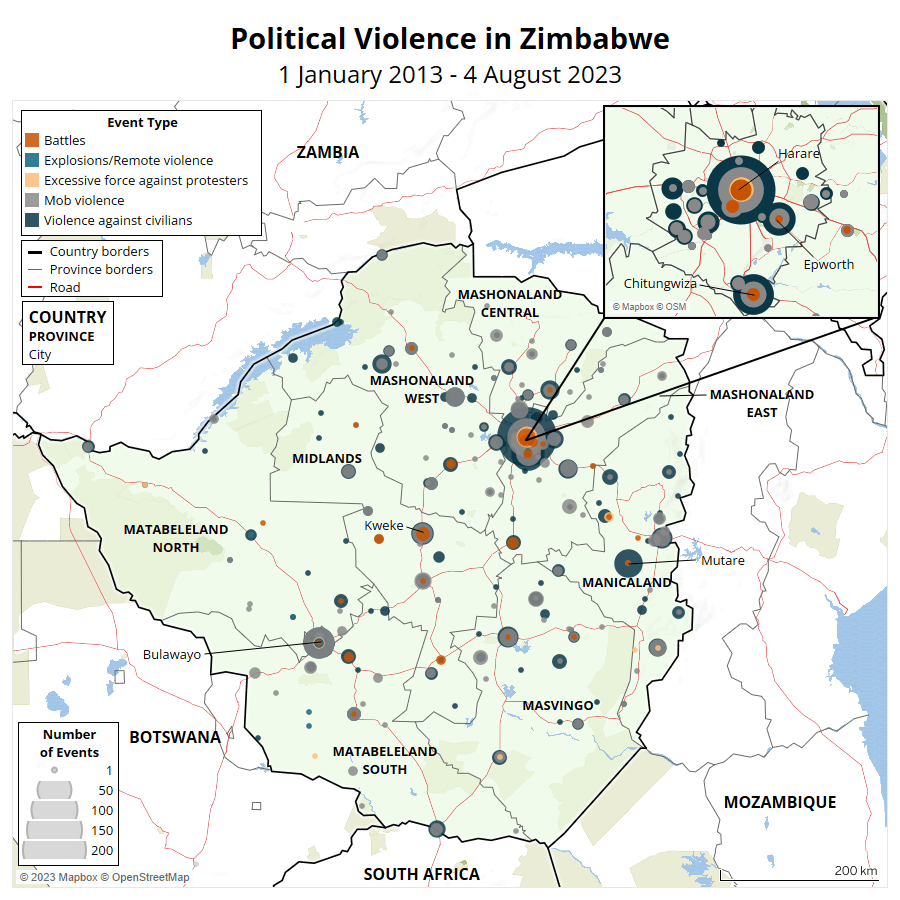

Overall, political violence in Zimbabwe is relatively low and consistent.11Although not consistently: the 2013 election had a low rate of conflict; while the 2018 election had violent acts occur (including a police shooting of six people) in the protests surrounding the election results. See, BBC, ‘Zimbabwe election: Troops fire on MDC Alliance supporters,’ 1 August 2018 It typically occurs in the same places it has occurred repeatedly in the past (see map below). It manifests in two main forms: (1) sporadically violent contests over corruption or extraction opportunities from those inside ZANU-PF; and (2) police and/or ZANU-PF gangs attacking the opposition.12CCC rallies are frequently disrupted and/or banned by police and ZANU supporters attack its members Most violence involves police or ZANU-PF militias and is oriented towards protesters and civilians. In a testament to the ongoing violence directed at members of the opposition, CCC activist Tinashe Chitsunge was stoned to death on 3 August 2023 by alleged ZANU-PF supporters, after they attempted to storm an opposition rally in Glen View South, Harare. This is the first politically motivated killing ahead of this month’s elections, although a ZANU-PF spokesperson has denied the suspects have any links with the party.13Voice of America, ‘Witnesses: Zimbabwe Ruling Party Followers Killed Opposition Supporter,’ 4 August 2023 Harassing the opposition is a common practice in African competitive autocracies.14The Conversation, ‘From Algeria to Zimbabwe: how Africa’s autocratic elites cycle in and out of power,’ 24 January 2022 Zimbabwe’s violence patterns shift and intensify when ZANU-PF is not able to secure voting or corruption outcomes.

The last election in 2018 returned results at 52.3% to ZANU-PF’s EDM (just above the rate that triggers a run-off), while the opposition front led by MDC’s Chamisa gained 44%. But of the 270 parliamentary seats, ZANU-PF won 179 to the opposition’s 91 (still an increase of 17 seats for the opposition). There were widespread (but poorly proven) allegations of electoral fraud in 2018. These claims have been echoed ahead of the 2023 elections, as several activists have again started declaring the upcoming elections to be rigged, despite restrictions under the Patriot Act.15AfricaNews, ‘Rough campaign for opposition as Zimbabwe gears up for elections,’ 20 July 2023 The 5.7 million registered to vote in 2018 and the 6.6 million registered in 2023 certainly do not have the ability to make a choice based on an even playing field. This election suggests that, by and large, the same contingent will line up to support the respective parties: urban areas will support the CCC, and rural voters will largely support ZANU-PF – not always because of approval, but rather the incumbency advantages of the ZANU-PF party and its rural and dominant political structures. Rural voters turn out in large numbers because the members of the ZANU-PF party often force them to. Moreover, the government does not allow Zimbabweans living abroad to vote, which is likely to hurt the opposition. All in all, the result is a function of the ‘get out the vote’ campaign first and foremost.

Without knowing whether rural voters will support EDM and ZANU-PF in high enough numbers in their strongholds, a definitive prediction cannot be made as to whether violence will spike during this election. However, if there is intense violence, it will likely be highest in ZANU-PF’s presumed strongholds: between the first and run-off elections in 2008, significant violence occurred in the cities of Harare and Bulawayo – where the opposition has high support; but more took place in areas that are traditionally ZANU-PF areas of the Midlands and Mashonaland West, Central, and East.16Tiziana Corda, ‘For things to remain the same, how many things have to change? Elite continuity and change after leadership changes,’ Democratization, 3 May 2023 The objective of the violence was to punish and turn voters who had been expected to vote ZANU-PF in the first round, but did not. Their dissension and defections can be monitored, and those votes could be turned for the run-off with pressure from violence and local authorities.

Unclear Political Succession and Factionalization

How likely is ZANU-PF voter and elite defection at the local level? As aforementioned, in Zimbabwe’s current political climate, there is a high level of economic and social malaise. These issues are mirrored in ZANU-PF, where many factions exist and fewer resources are being shared around and the churn of opportunities and positions is non-existent. But crucially: this is likely to be Mnangagwa’s last election, as he has reached 80 years old. Who will come next? There are no more ‘original’ war veterans, and waiting in the wings are those whom Mnangagwa purged from the party and state (for example, Saviour Kasukuwere, a former ZANU-PF heavyweight and leader of the late Mugabe-era faction ‘Generation 40’ who attempted to shoehorn Grace Mugabe into power).17Saviour Kasukuwere has been banned from running as an independent in the election. The end of this reign is important because the jostling in ZANU-PF elite circles will be fierce and directed towards building loyalty for the presumed successor (whomever that may be). With any change in government, the ZANU-PF political machine will be recalibrated. If that is happening too early (as in, during this election), then the outcome for the top of the ZANU-PF hierarchy is in question.

This is a present concern because if ZANU-PF cannot depend on local party apparatchiks and local administrators to return the ‘right results’ and for the ‘right candidate’ (ie. EDM), then they risk losing this election. In a repeat of 2008, those at the ZANU-PF center will go to extreme lengths to hold onto power, and this leads to inflated risks to local administrators and voters living in ‘defecting’ areas. If this context is repeated, violence directed at them in order to ‘correct’ the vote before the run-off is likely. In short, there are multiple political games being played out in ZANU-PF, and each of them will turn on these election results.