The Violent Politics of Bangladesh’s 2024 Elections

4 January 2024

Introduction

Elections in Bangladesh have historically been marked by violence between the country’s two dominant political parties, the ruling Awami League (AL) and the opposition Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP). The upcoming elections scheduled for 7 January are no different. Violence has already been on the rise in the months leading up to the elections, in which Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina will seek re-election for the fourth consecutive term.

Much of the recent unrest has centered around concerns about the AL’s ability to hold a free and fair election. The BNP has called for the formation of a neutral caretaker government to administer the elections. The AL has rejected this demand, giving way to increased BNP-led demonstration events1ACLED codes all clashes occurring during announced strikes and blockades as violent demonstration events. Since the end of October, the BNP has continuously announced strikes and blockades, so the violence during these events has been coded as violent demonstrations. that have often turned violent. The BNP’s decision to boycott the elections, motivated by its misgivings over the election process, suggests that the results are likely to be contested, increasing the risk of post-electoral violence. As the AL looks set to hold onto power, violence within the party is also cause for concern. Competition for power among AL factions can be seen in post-election periods as rivals seek party and government appointments.

Violence Spikes Amid Interparty Rivalry

Bangladesh’s political landscape is dominated by rivalry between two political parties — the socialist-secular AL and the conservative-nationalist BNP. In addition to ideological differences, the rivalry is personal and rooted in historical grievances between Prime Minister and AL chair Sheikh Hasina and BNP chair Khaleda Zia, who are widely referred to as the ‘Battling Begums.’2Justin Rowlatt, ‘Bangladesh grows tired of the Battling Begums,’ BBC, 11 February 2018 Competition between the AL and BNP often turns violent both during and beyond election cycles, with frequent attacks against political opponents, street clashes between the parties, violent anti-government demonstrations, and state repression of demonstrations. Student, youth, and labor wings of the parties are often involved in such violence.

Election-related violence has often stemmed from dissatisfaction over the conduct of elections. Elections in the late 1990s and early 2000s were administered by an interim, nonpartisan government, which meant that power would routinely alternate between the two main parties.3International Crisis Group, ‘Mapping Bangladesh’s Political Crisis,’ 9 February 2015 The AL government abolished this system in 2011 after the previous caretaker government, backed by the military, held onto power beyond the mandated three months and delayed elections by almost two years. Since the abolition of the system, however, the AL has remained in power, prompting concerns over the fairness of elections. The 2014 elections were held without the formation of a caretaker government, leading to a BNP boycott and countrywide unrest.4Human Rights Watch, ‘Bangladesh: Elections Scarred by Violence,’ 29 April 2014; International Crisis Group, ‘Mapping Bangladesh’s Political Crisis,’ 9 February 2015; Human Rights Watch, ‘Democracy in the Crossfire,’ 29 April 2014 While the BNP did participate in the 2018 elections, party leader Zia was disqualified due to her conviction in two corruption cases. The AL was re-elected to power amid widespread allegations of vote rigging.5BBC, ‘Bangladesh election: Opposition demands new vote,’ 30 December 2018 Reprisals and the partisan targeting of opponents followed, prompting the United Nations to call for an independent investigation into the elections.6United Nations Human Rights, ‘Bangladesh elections: Hold those responsible accountable for “violent attacks and intimidation,”’ 4 January 2019

Prime Minister Hasina, who has enjoyed high approval ratings during her tenure, has continued to resist calls to dissolve her government and hold the 2024 elections under a caretaker government.7International Republican Institute, ‘New Survey Research for Bangladesh Shows Dissatisfaction with Country’s Direction, Support for Prime Minister Hasina, Calls for Caretaker Government,’ 8 August 2023 Hasina faces allegations of misusing state institutions to repress political opponents and influence the elections.8Human Rights Watch, ‘Bangladesh: Violence Erupts Amid Demands for Fair Election,’ 1 November 2023 The BNP, after many years in opposition, has experienced a surge in popularity, as have other opposition forces.9International Republican Institute, ‘New Survey Research for Bangladesh Shows Dissatisfaction with Country’s Direction, Support for Prime Minister Hasina, Calls for Caretaker Government,’ 8 August 2023 Concerns over ensuring the impartial conduct of elections have overshadowed the pre-election period. According to a survey by the International Republican Institute, only a minority of the electorate believes that the upcoming elections will be free and fair.10International Republican Institute, ‘New Survey Research for Bangladesh Shows Dissatisfaction with Country’s Direction, Support for Prime Minister Hasina, Calls for Caretaker Government,’ 8 August 2023; Mubashar Hasan, ‘What Do Bangladeshis Think About Democracy, Human Rights, and Elections?,’ The Diplomat, 26 September 2023

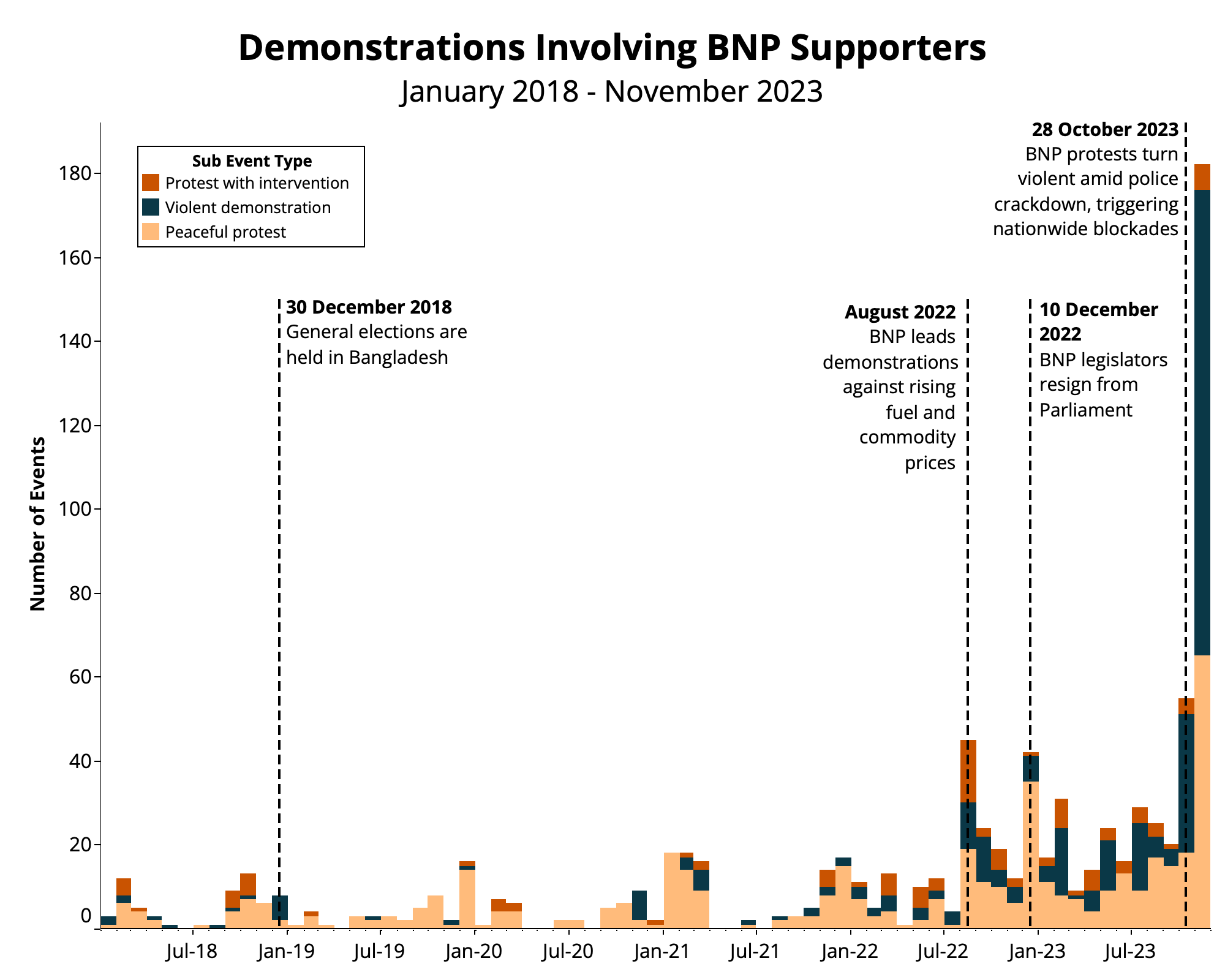

Following a series of anti-government demonstrations, during a rally on 10 December 2022, all seven BNP legislators resigned from Parliament in opposition to what they claimed to be an “illegal” AL government, a reference to the contested acceptance of the 2014 and 2018 election results.11Faisal Mahmud, ‘Bangladesh opposition stages protests as it challenges PM Hasina,’ Al Jazeera, 11 December 2022 Since then, the BNP has launched a series of nationwide demonstrations demanding the resignation of the AL government and the holding of the 2024 elections under a caretaker government. Between December 2022 and November 2023, ACLED records over 420 demonstrations involving BNP supporters. Of these, 43% of demonstrations turned violent, descending into clashes between BNP supporters on one side and AL supporters and police on the other (see figure below).

The demonstrations, which tap into popular anxieties about the economic downturn, have seen large turnouts.12Hannah Ellis-Petersen and Shaikh Azizur Rahman, ‘Full prisons and false charges: Bangladesh opposition faces pre-election crackdown,’ The Guardian, 10 November 2023 Police crackdown on the opposition has also been heavy-handed, with security forces firing live ammunition at demonstrators. At least five people have been killed in clashes with police since December 2022. Tensions between police and BNP came to the fore during a large rally in Dhaka city on 28 October 2023, when hundreds of BNP supporters clashed with police, resulting in a death on each side.13Oliver Slow, ‘Bangladesh opposition chief Alamgir arrested after clashes,’ BBC News, 30 October 2023 The BNP subsequently intensified its demonstrations, holding nationwide blockades in support of its demands. In order to enforce the blockades, opposition supporters have resorted to widespread vandalism and arson, setting ablaze buses and trains. On 19 December 2023, in the deadliest demonstration so far, demonstrators set ablaze a train near Dhaka city, resulting in the reported deaths of at least four passengers.

Police have also detained thousands of BNP supporters ahead of and following demonstrations.14Human Rights Watch, ‘Bangladesh: Violence Erupts Amid Demands for Fair Election,’ 1 November 2023 On 29 October 2023, police arrested the BNP’s most senior leader in Bangladesh, Secretary General Mirza Fakhrul Islam Alamgir, in connection with violence during the BNP’s demonstrations.15Oliver Slow, ‘Bangladesh opposition chief Alamgir arrested after clashes,’ BBC News, 29 October 2023 BNP chair Zia remains under house arrest following her 2018 conviction on charges of corruption, while her son and acting chairman Tarique Rahman, also convicted on corruption charges, is living in London in self-imposed exile.16Dawn, ‘Khaleda Zia’s son sentenced in absentia for graft,’ 3 August 2023 Police detention has also proved deadly, with at least eight BNP members dying in police custody since 28 October 2023.17New Age Bangladesh, ‘Another BNP leader dies in jail custody,’ 29 December 2023 Family members have blamed custodial assaults and lack of timely access to medical treatment for the deaths.18Shaikh Azizur Rahman, ‘Six Bangladesh Opposition Activists Die in Custody,’ VOA News, 19 December 2023; New Age Bangladesh, ‘Another BNP leader dies in jail custody,’ 29 December 2023 Human rights bodies have expressed concern over the excessive use of force during demonstrations and the repression of political opponents.19Amnesty International, ‘Bangladesh: Repeated cycle of deaths, arrests and repression during protests must end,’ 30 October 2023; Human Rights Watch, ‘Bangladesh: Violence Erupts Amid Demands for Fair Election,’ 1 November 2023

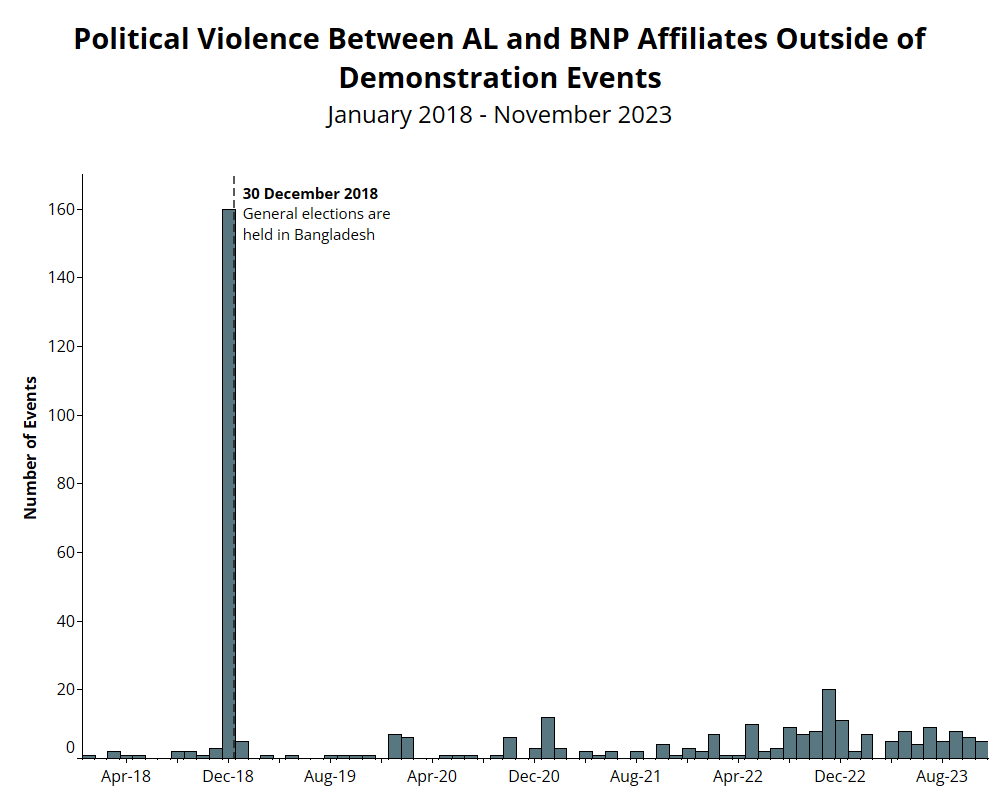

The BNP-led anti-government demonstrations and the crackdown against them have heightened political divisions in the country.20Al Jazeera, ‘No EU election team for Bangladesh amid concerns over free and fair vote, 22 September 2023 In contrast to the 2018 elections, violence in the run-up to the 2024 elections has primarily occurred within demonstration events. As the BNP participated in the 2018 elections, there were fewer violent demonstrations in the pre-election period as the party avoided contesting the conduct of the elections. Instead, ACLED records a dramatic increase in violence between the BNP and AL outside of demonstrations during the election period in December 2018, with most events recorded before election day on 30 December (see figure below). The pre-2024 election period has also seen violence between the parties outside of demonstrations, with a nearly three times increase in the number of such events recorded in the 12 months before the 2024 elections as the number recorded in 2018.

The conduct of the upcoming elections and the likelihood of violence has drawn concern from the international community. Due to worries over electoral irregularities, the European Union has declined to send a full-fledged observer mission to the country. The UN will also not send observers.21Dhaka Tribune, ‘UN will not send mission to observe Bangladesh polls,’ 30 November 2023 The United States has stepped up its pressure on Bangladesh to ensure free and fair elections, announcing a new visa policy that would place restrictions on people “found to have been responsible for, or complicit in, undermining the democratic election process in Bangladesh.”22Benjamin Parkin, ‘Bangladesh pushes back at US over visa curbs ahead of election,’ Financial Times,1 October 2023 This has led to tensions between Bangladesh and the US. At the same time, China has expressed support for protecting Bangladesh’s sovereignty and non-interference in its internal affairs.23Ananth Krishnan and Kallol Bhattacherjee, ‘China says will back Bangladesh against “external interference,”‘ The Hindu, 25 August 2023 These contrasting responses represent ongoing geopolitical tensions in the region.

A Turbulent Post-Election Scenario

As the election approaches, large-scale BNP-led rallies and strikes are likely to continue.24Arild Engelsen Ruud, ‘As Elections Near, 3 Scenarios for Bangladesh,’ The Diplomat, 14 August 2023 The BNP, which missed the 30 November deadline to submit nominations,25La Prensa Latina, ‘Opposition boycott sets stage for one-sided Bangladesh election,’ 30 November 2023 has held to its decision to boycott the elections. Although smaller parties have filed nominations, the BNP boycott will likely mean the AL will continue to stay in power amid rising dissatisfaction.26Snigdhendu Bhattacharya, ‘Won’t join farcical vote’: Bangladesh opposition leader ahead of election, Al Jazeera, 29 November 2023

The results are likely to be disputed given the sustained campaign questioning the impartiality of the electoral process that the BNP and other like-minded opposition parties have waged. In this way, the upcoming elections resemble the 2014 elections, which the BNP also boycotted amid demands for the formation of a neutral caretaker government to administer the elections. The 2014 elections saw high levels of political violence, which continued even after the elections, as opposition parties contested the legitimacy of the newly elected government.27Al Jazeera, ‘Clashes rock Bangladesh on poll anniversary,’ 5 January 2015 The risk of a similar continuation, or even escalation, of political unrest in the aftermath of the 2024 elections thus remains high.

Visuals in this report were produced by Ana Marco.