Political Repression and Militant Targeting Set the Stage for Pakistan’s 2024 Elections

1 February 2024

After nearly two years of political turmoil, Pakistan is set to hold elections for its national and provincial assemblies on 8 February. The elections will take place at a turbulent time in Pakistan’s history, as it reels from multiple crises, including an economic downturn, tensions along its disputed borders, and rising militancy that has strained relations with neighboring Iran and Afghanistan.1International Crisis Group, ‘Pakistan: At the Tipping Point?,’ 12 May 2023 The resulting instability has served to strengthen the hand of the military, the dominant force in Pakistani politics. Claims of military interference in the democratic process are rife ahead of the 2024 elections, with political disorder and militant attacks characterizing the run-up to the vote.

Since Pakistan’s independence in 1947, the military has directly ruled the country for over three decades and continued to influence politics during civilian rule by selectively propping up leaders.2Abid Hussain, ‘“Election engineering”: Is Pakistan’s February vote already rigged?,’ Al Jazeera, 12 January 2024 During the previous elections in 2018, former Prime Minister Imran Khan was believed to have been the chosen one, with many analysts attributing the victory of his party, the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaaf (PTI), to the military’s decisive support.3Omar Waraich, ‘It’s Time for the Generals to Let Go in Pakistan,’ Foreign Policy, 18 May 2023; Hannah Ellis-Petersen and Shah Meer Baloch, ‘Pakistan parliament ousts Imran Khan in last-minute vote,’ The Guardian, 9 April 2022 In 2024, however, the tables seem to have turned. Khan, currently imprisoned and disqualified from contesting the elections, is involved in a bitter standoff with the military, and PTI supporters are facing repression at the hands of state forces.4Al Jazeera, ‘Pakistan’s Imran Khan gets bail in state secrets case ahead of key election,’ 22 December 2023

The upcoming elections will see an embattled PTI challenge the traditionally dominant parties of Pakistani politics — the Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (PML-N) and the Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP). The military favorite this time around appears to be former Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif, from the PML-N, who recently returned to Pakistan after four years in self-imposed exile in London following his conviction in a corruption case.5Tarhub Asghar and Simon Fraser, ‘Nawaz Sharif: The Pakistan army’s one-time arch-rival returns,’ BBC News, 20 October 2023 In a convenient turn of events for the PML-N, Pakistan’s Supreme Court in early January also overturned lifetime bans on people with criminal convictions contesting elections, paving the way for another Sharif premiership.6Associated Press, ‘Pakistan’s court scraps a lifetime ban on politicians with convictions from contesting elections,’ 8 January 2024 Days later, one of the judges involved in the 2017 judgment disqualifying Sharif from holding public office prematurely resigned from the Supreme Court.7Sajjad Hussain, ‘Pakistan Supreme Court’s second senior-most judge resigns,’ The Print, 11 January 2024

These developments came after the elections, originally expected to take place in November 2023, were postponed. While the official reason was to allow for the completion of a delimitation exercise, the opposition believes the delay was intended to give the military more time to manipulate their conduct.8Allison Meakem, ‘The Road to Power in Pakistan Runs Through the Military,’ Foreign Policy, 2 January 2024 In light of the military’s perceived role in managing the pre-poll environment, few expect the February elections to be free and fair.9Munir Ahmed, ‘Pakistan human rights body says an upcoming election is unlikely to be free and fair,’ Associated Press, 1 January 2024; Abid Hussain, ‘“Election engineering”: Is Pakistan’s February vote already rigged?,’ Al Jazeera, 12 January 2024 Like with previous elections, concerns also abound over the safety of party candidates and supporters, who have been a target of violent militant groups seeking to disrupt the electoral process.

PTI supporters rise against the military

Throughout Pakistan’s checkered democratic history, no elected prime minister has ever completed a full five-year term in office.10Al Jazeera, ‘No Pakistani prime minister has completed a full term in office,’ 9 April 2022 Khan was no exception. In April 2022, less than four years after being elected prime minister, Khan resigned from office following a no-confidence motion brought about on grounds of economic mismanagement.11Asif Shahzad and Syed Raza Hassan, ‘Pakistan’s Prime Minister Imran Khan ousted in no-confidence vote,’ Reuters, 9 April 2022 He accused the military of orchestrating his ouster amid an ongoing power struggle regarding the appointment of the chief of Pakistan’s powerful Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) agency.12Cyril Almeida, ‘What led to leader Imran Khan’s downfall in Pakistan?,’ Al Jazeera, 10 April 2022; Hannah Ellis-Petersen and Shah Meer Baloch, ‘Imran Khan accuses Pakistan’s military of ordering his arrest,’ The Guardian, 14 May 2023 The PTI government was replaced by the Pakistan Democratic Movement (PDM), a coalition government comprising the conservative PML-N and the center-left PPP, along with other smaller parties.13Dawn, ‘Shehbaz Sharif elected prime minister of Pakistan,’ 11 April 2022

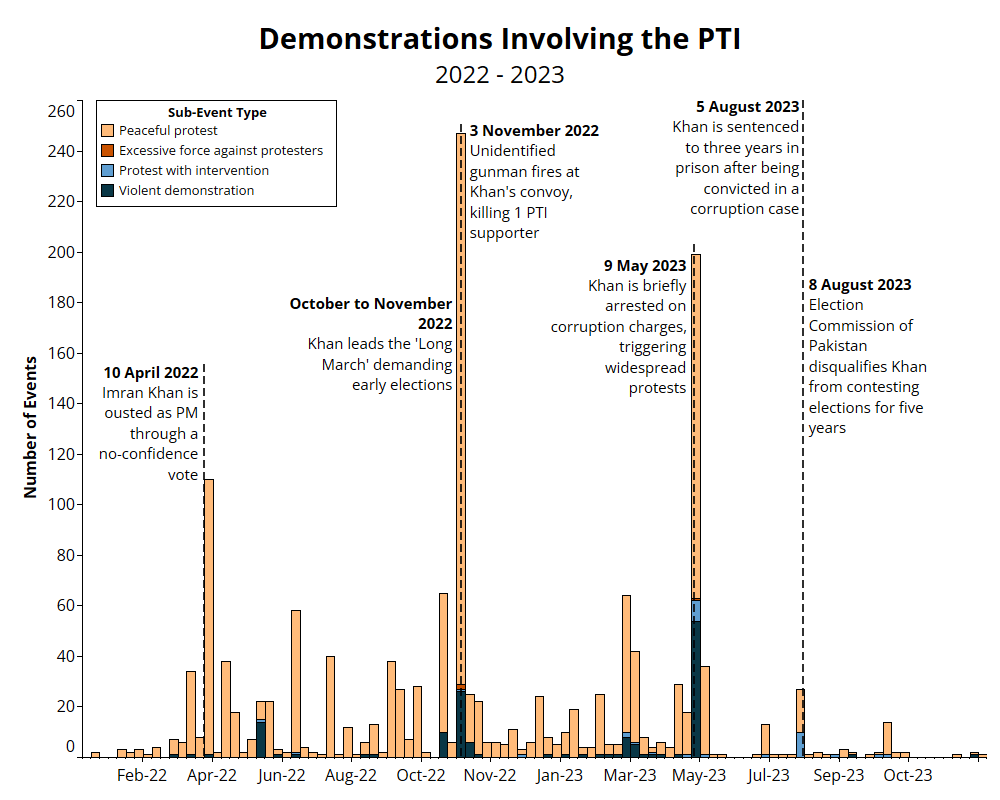

In his resignation speech, Khan called on his supporters to take to the streets in mass protest.14Hannah Ellis-Petersen and Shah Meer Baloch, ‘Pakistan parliament ousts Imran Khan in last-minute vote,’ The Guardian, 9 April 2022 He began a nationwide ‘Long March’ from Pakistan’s most populous province, Punjab, to the capital, Islamabad, demanding early elections. On 3 November 2022, during a protest in Punjab’s Wazirabad town, a gunman fired at Khan’s convoy, wounding him and killing a PTI supporter. PTI supporters called the incident an assassination attempt, with Khan placing the blame on the ruling government and military.15Shah Meer Baloch, ‘Imran Khan wounded in “assassination attempt” in Pakistan,’ The Guardian, 3 November 2022

Ongoing tensions between Khan and the political establishment spilled over in May 2023, when Khan was arrested on corruption charges.16Hannah Ellis-Petersen and Shah Meer Baloch, ‘Imran Khan accuses Pakistan’s military of ordering his arrest,’ The Guardian, 14 May 2023 PTI supporters mobilized across the country, organizing demonstrations in hundreds of locations. Of these, 21% of demonstrations turned violent, with demonstrators attacking government and military properties, including the residences of high-ranking military officers.17Omar Waraich, ‘It’s Time for the Generals to Let Go in Pakistan,’ Foreign Policy, 18 May 2023 The proportion of violent demonstrations was nearly double that seen during the PTI’s Long March, when only 11% of the demonstrations involved violence (see graph below). Given the military’s exalted position in Pakistani public life, these displays of open irreverence against the military were unprecedented.18Salman Masood and Christina Goldbaum, ‘Droves of Imran Khan’s Allies Defect as Military Ramps Up Crackdown,’ The New York Times, 14 June 2023 Khan denied his supporters’ complicity in the violence and, in turn, accused the government and military of orchestrating the violence to malign the PTI.19Shah Meer Baloch and Hannah Ellis-Petersen, ‘Imran Khan alleges “reign of terror” as supporters face trial in military courts,’ The Guardian, 19 May 2023

In response, Pakistani authorities launched a brutal crackdown against the opposition. Security forces violently dispersed demonstrators, using live ammunition, tear gas, and baton charges. During the demonstrations in May 2023, ACLED records at least 11 people killed in clashes with police. Such deadly use of force by police against party members is rare in Pakistan. Police also arrested thousands of PTI supporters and senior leaders, with the party claiming that many of its members were tortured and mistreated in custody.20Shah Meer Baloch and Hannah Ellis-Petersen, ‘Imran Khan alleges “reign of terror” as supporters face trial in military courts,’ The Guardian, 19 May 2023; Al Jazeera, ‘Pakistan army vows to punish “planners” of violent protests,’ 7 June 2023 On the other hand, dozens of senior members resigned from the party amid claims of pressure from authorities.21Salman Masood and Christina Goldbaum, ‘Droves of Imran Khan’s Allies Defect as Military Ramps Up Crackdown,’ The New York Times, 14 June 2023 Human rights groups expressed concern over the clampdown on political opposition through mass arrests and arbitrary detentions.22Amnesty International et al., ‘Pakistan: End Crackdown On Political Opposition,’ 23 May 2023; Benjamin Parkin and Farhan Bokhari, ‘Pakistan launches crackdown on Imran Khan’s party,’ Financial Times, 26 May 2023

The actions against the PTI’s rank and file have weakened the party ahead of the vote. Although legal actions against senior PTI leaders had often instigated popular reaction among the public, demonstrations by party supporters in the last quarter of 2023 were approximately half of that in the third quarter, and 90% fewer compared to the second quarter, suggesting a reduced mobilization capacity. The party’s presence on the campaign trail has been muted, as it continues to face legal and administrative challenges. It has lost the right to use its electoral symbol, the cricket bat, meaning that PTI candidates will have to stand in the elections using individual symbols.23Asif Shahzad, ‘Pakistan’s Imran Khan’s party loses cricket bat electoral symbol,’ Reuters, 14 January 2024 This is a major setback in a country like Pakistan, where, due to low levels of literacy, voters rely on symbols to easily identify their party of choice. Authorities have also rejected the nomination papers of several candidates, denied permission to hold conventions, sealed party offices, and disrupted internet services to coincide with the PTI’s digital campaigns.24Ali Waqar and Imran Gabol, ‘Rejections aplenty for PTI as scrutiny phase of nomination papers for elections ends,’ Dawn, 30 December 2023; Dawn, ‘PTI seeks permission for rallies, election prep meetings with Imran,’ 28 December 2023; Deccan Herald, ‘Crackdown on Imran Khan’s party continues as Pak police seals Central Punjab office,’ 5 December 2023; Dawn, ‘Nationwide disruption to social media platforms amid PTI virtual event: Netblocks,’ 20 January 2024 For their part, the government has denied claims of a crackdown against the PTI, claiming instead to apply electoral regulations.25DW News, ‘Pakistan: PTI supporters decry pre-election crackdown,’ 16 January 2024

Militant attacks threaten a fragile democracy

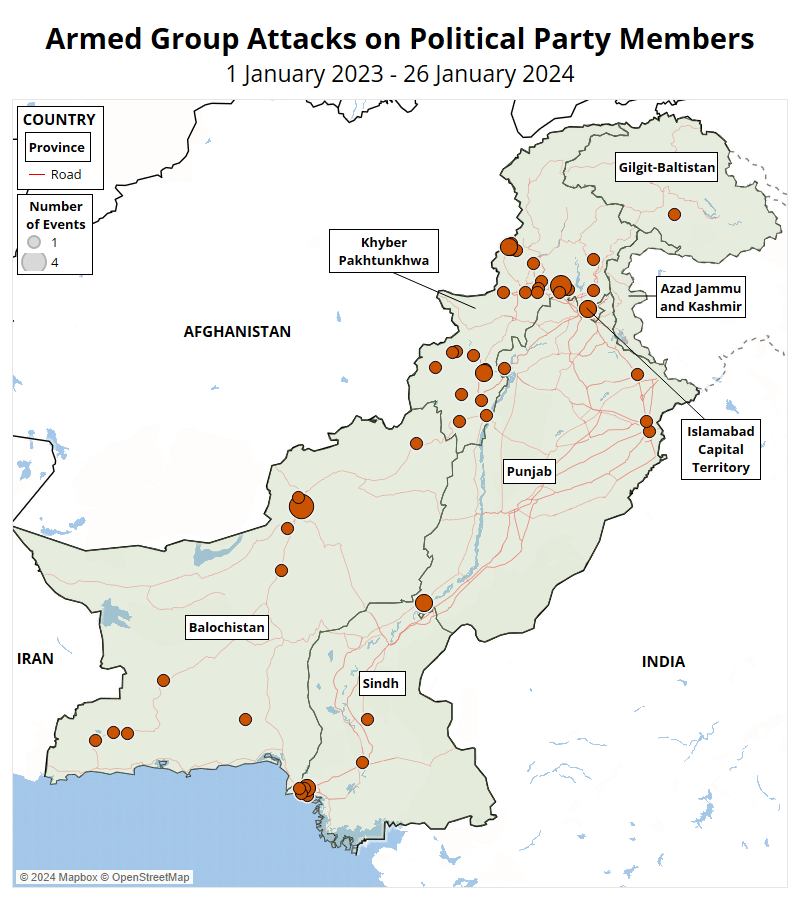

A meddling military is not the only threat facing Pakistan’s democracy. In the past, the pre-election period has been marred by militant attacks targeting political parties. While the actors, motivations, and targets behind the attacks have varied, most of the violence has clustered in the border provinces of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Balochistan, as has been the case in this electoral cycle (see map below).

In Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Islamist militant groups pose the biggest threat, as they continue their violent campaign for greater autonomy in the tribal regions and the imposition of an Islamic political system across Pakistan. The Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), which ended its ceasefire agreement with the Pakistani government in November 2022, is the most active among these groups.26Reuters, ‘Taliban militants in Pakistan end ceasefire with government – spokesman,’ 28 November 2022 The TTP and its allies target political parties that they regard as being complicit with Western countries in carrying out anti-militancy operations.27Abid Hussain, ‘Pakistan Taliban threatens top political leadership including PM,’ Al Jazeera, 4 January 2023 The TTP has previously singled out the PPP, PML-N, and the secular Pashtun Awami National Party (ANP), while sparing the PTI, which favored peace talks with the group.28Abid Hussain, ‘Pakistan Taliban threatens top political leadership including PM,’ Al Jazeera, 4 January 2023; Asma Jehangir, ‘Liberal parties under siege: With their targeting by terrorists, Pakistan’s elections are being held in a climate of fear,’ The Times of India, 1 May 2013 On the other hand, the Islamic State Khorasan Province (ISKP) considers all political parties that participate in the secular democratic process, including religious parties, as legitimate targets.29Zia Ur Rahman, ‘Why is the militant ISKP attacking the JUI-F in Bajaur?,’ Dawn, 2 August 2023 In July 2023, the ISKP targeted the Islamist Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam (Fazl) (JUI-F), an ally of the Taliban, in a deadly suicide bombing, partly as a spillover of its ongoing rivalry with the Taliban in Afghanistan.30Zia Ur Rahman, ‘Why is the militant ISKP attacking the JUI-F in Bajaur?,’ Dawn, 2 August 2023

The southwestern province of Balochistan grapples instead with a decades-long separatist insurgency and rising violent Islamist movements. Ethnic Baloch separatists oppose participation in the electoral process, which they believe amounts to collusion with the Pakistani political and military establishment.31Zia Ur Rahman, ‘Under militancy’s shadow, political canvassing takes a back seat,’ Dawn, 22 January 2024; Asian News International, ‘BLA appeals to Baloch nation to boycott Pak polls,’ 25 June 2018 The Baloch Liberation Front (BLF), one of the most active Baloch armed groups, and the Baloch Raji Aajoi Sangar (BRAS), an alliance of major Baloch separatist groups, have called for a boycott of the upcoming elections, implying a threat to those participating in the elections.32Zia Ur Rahman, ‘Under militancy’s shadow, political canvassing takes a back seat,’ Dawn, 22 January 2024

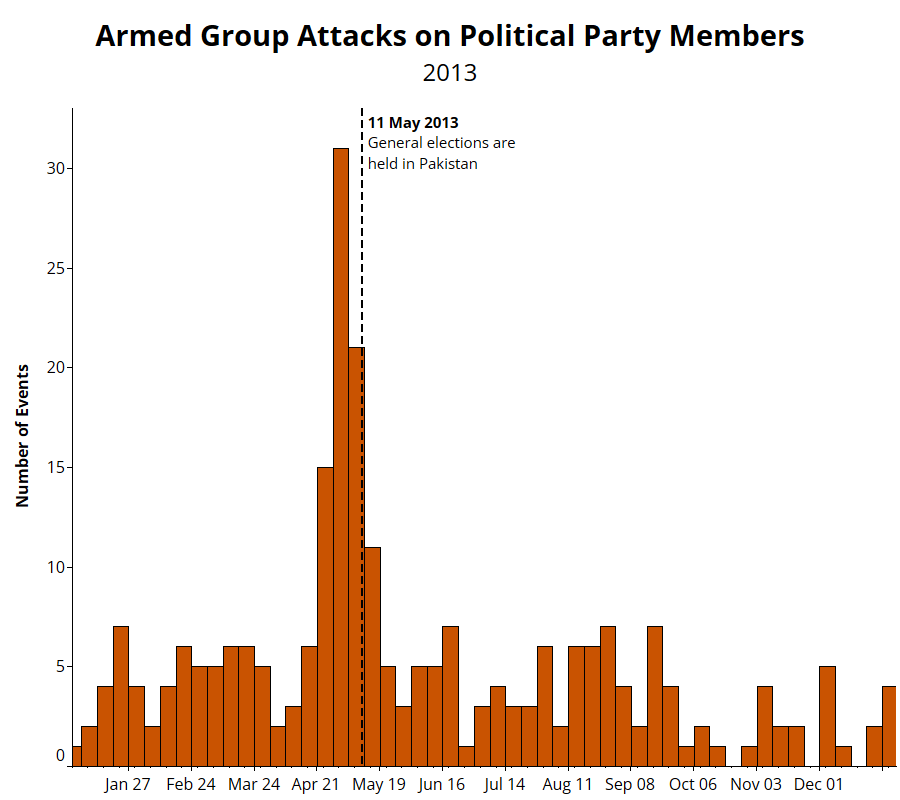

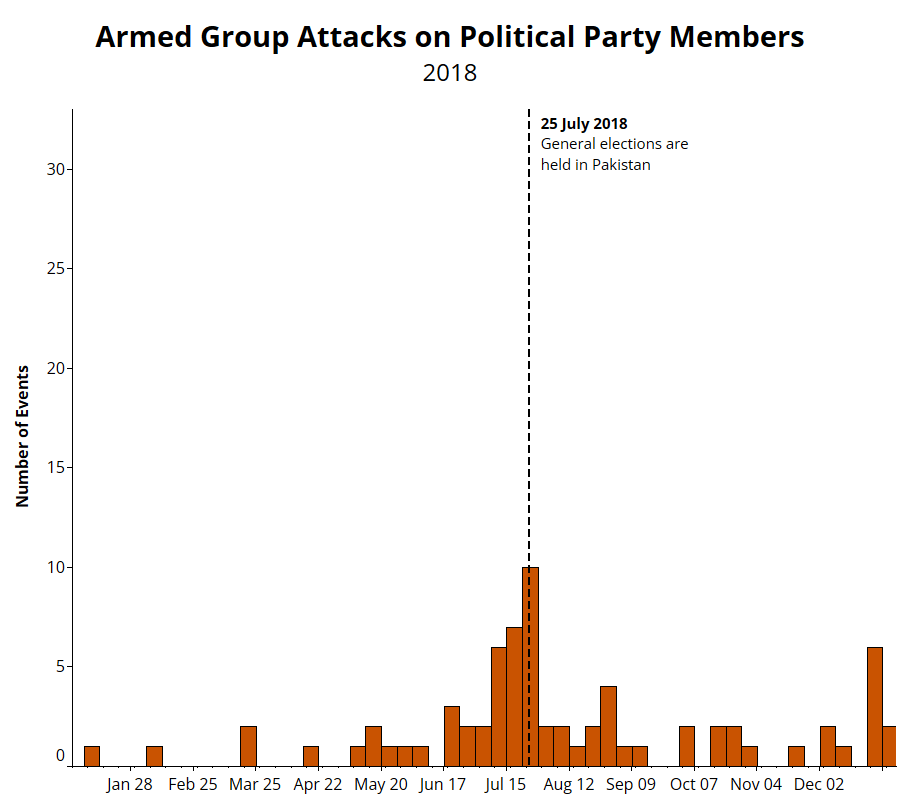

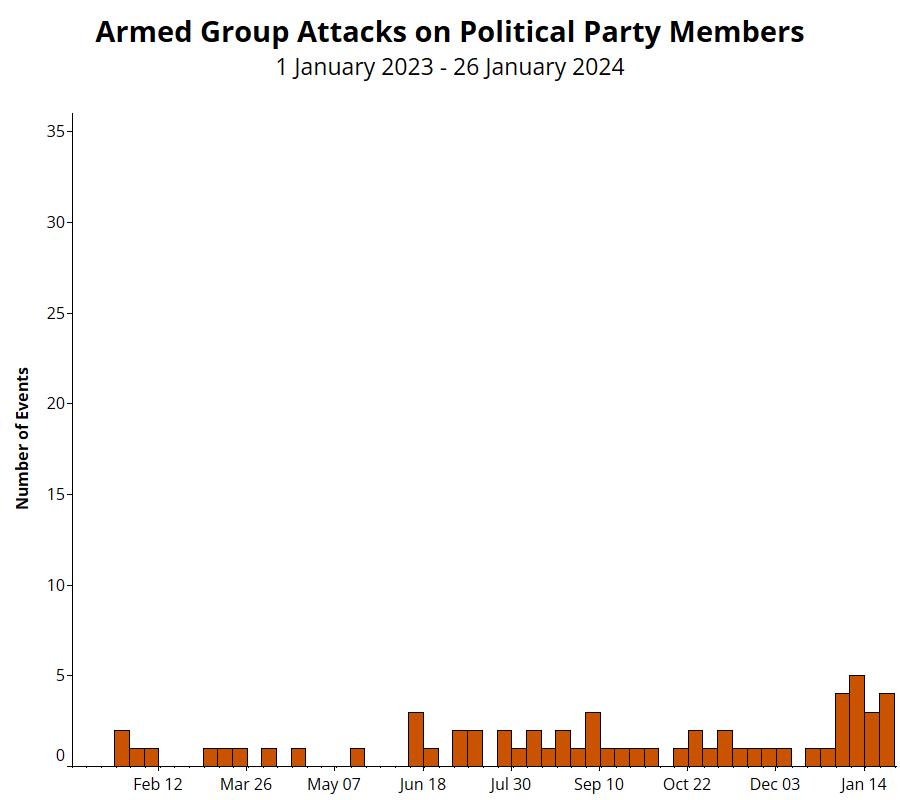

In the lead-up to the 2024 elections, thus far, ACLED records no less than 24 instances in which armed groups staged attacks against members of political parties. This is comparable to the number recorded ahead of the 2018 elections, but significantly lower than the over 100 events recorded before the 2013 elections (see graphs below). However, while the TTP had singled out several political parties as targets in 2013, it has now pledged not to attack electoral rallies, claiming that its targets are limited to military and security forces only.33M Ilyas Khan, ‘Pakistan election: Taliban threats hamper secular campaign,’ BBC News, 5 April 2013; Munir Ahmed, ‘Pakistani Taliban pledge not to attack election rallies ahead of Feb. 8 vote,’ Associated Press, 25 January 2024 The announcement came on the heels of a rare meeting between the JUI-F chief and the Taliban’s top leadership in Afghanistan, where they are believed to have discussed the Pakistani government’s concerns over rising TTP activity.34Tahir Khan, ‘Afghan PM meets JUI-F’s Fazlur Rehman, says Kabul “does not intend to harm Pakistan”, Dawn, 8 January 2024 Pakistan has often accused Afghanistan, which enjoys close ties with the TTP, of providing safe haven to the TTP.35Reuters, ‘Pakistan PM says expulsion of Afghans a response to Taliban non-cooperation,’ 8 November 2023 At the same time, a change in campaigning tactics by political leaders, some of whom have eschewed the traditional large gatherings in favor of a more subdued campaign, could also explain the decline in the number of high-fatality attacks compared to 2013.36Zia Ur Rahman, ‘Under militancy’s shadow, political canvassing takes a back seat,’ Dawn, 22 January 2024

Nevertheless, political parties remain wary of the security risks. Senators from Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Balochistan recently passed a nonbinding resolution seeking to delay the elections until the law and order situation improves.37Shahjahan Khurram, ‘Pakistan’s election regulator signals no delay to upcoming election,’ Arab News, 15 January 2024 Their fears are not unwarranted. Local Islamic State affiliates including ISKP, which carried out the deadliest attack targeting a political party in the last year, have warned of upcoming attacks in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Balochistan, and Sindh (see map below).38The Khorasan Diary, ‘TKD MONITORING: ISPP Pamphlets Threaten Upcoming Elections in Pakistan,’ 24 January 2024; X, @khorasandiary, 21 December 2023 Analysts have also cautioned that similar pledges by the TTP in the past have not deterred its more independently-minded commanders or affiliate groups, like the newly formed Tehreek-e-Jihad Pakistan (TJP), from carrying out attacks.39Zia Ur Rahman, ‘Under militancy’s shadow, political canvassing takes a back seat,’ Dawn, 22 January 2024

Looking Forward

Within the prevailing political and security situation, effective participation by political parties and citizens in the electoral process remains questionable. Campaigning activities have been restrained in the run-up to the elections while the crackdown against the PTI has continued unabated.40Abid Hussain, ‘“Used to be a festival”: Why Pakistan is seeing a subdued election campaign,’ Al Jazeera, 19 January 2024 Just over a week before polling day, Khan, who has been in jail since August 2023, was sentenced to 10 and 14 years’ imprisonment on separate charges of leaking state secrets and corruption, respectively.41Simon Fraser and Caroline Davies, ‘Imran Khan: Pakistan former PM jailed in state secrets case as election looms,’ BBC News, 30 January 2024; Hannah Ellis-Petersen, ‘Imran Khan, Pakistan former PM, sentenced to 14 years in prison for corruption,’ The Guardian, 31 January 2024 Frustration among PTI voters, as well as safety concerns in areas engulfed in militant activity, may depress voter turnout at the polls. At the same time, any sign of internal turmoil could see the military use national security as a pretext to strengthen its grip on power. A government elected on the back of low public engagement, and facing a powerful military, is unlikely to improve the strength of Pakistan’s democracy.

Meanwhile, Khan has shown no signs of backing down — on the one hand, expressing confidence about the PTI springing a “surprise” on polling day and, on the other, claiming that any elections held in the current climate would be “a disaster and a farce.”42Malik Asad, ‘PTI to spring surprise on Feb 8, claims Imran,’ Dawn, 17 January 2024; Imran Khan, ‘Imran Khan warns that Pakistan’s election could be a farce,’ The Economist, 4 January 2024 He also continues to enjoy immense personal popularity among voters, boasting the highest approval rating among national leaders according to a Gallup poll conducted in December 2023.43Gallup Pakistan, ‘Gallup Pakistan Political Weather Report: 1 month before the General Election 2024,’ 10 January 2024 This suggests that the results, expected to be unfavorable to the PTI, are likely to be contested. Whether discontent over the results and the continued targeting of Khan translates into the mass mobilization seen earlier, however, will depend on how tightly the military controls the post-electoral environment.

Visuals in this report were produced by Ana Marco