Boiling Under the Lid:

Protest Potential Ahead of Russia’s 2024 Presidential Election

6 March 2024

Introduction

The upcoming presidential election in Russia is a carefully choreographed endorsement of Vladimir Putin’s perennial rule. Having spent nearly 25 years in power and scrapped term limits in 2020, President Putin is running virtually unopposed. Parliamentary parties have fielded second-tier candidates on the ballot, but none of them poses a real challenge to the incumbent. Opposition movements have been largely banned, and their leaders either thrown behind bars or exiled. Alexei Navalny, Putin’s nemesis, suddenly died in an Arctic prison a month before the election. While the death certificate claims natural causes, Navalny’s supporters accuse authorities of murder — even if induced by prison conditions, as Navalny spent more than a quarter of his time in custody in a punishment cell.1Reuters, ‘Navalny’s team says death certificate says he died of natural causes,’ 22 February 2024; Andrew Roth and Pjotr Sauer, ‘It’s a torture regime’: the last days of Alexei Navalny,’ The Guardian, 23 February 2024

Set to begin on 15 March and again held around the anniversary of Russia’s annexation of Crimea, the vote is occurring against the backdrop of a full-fledged war against Ukraine, which triggered the near-complete eradication of open dissent. Despite the perception of absolute control over Russian society, ACLED data suggest a pent-up potential for protests. This report traces demonstration trends since Putin’s last re-election, in 2018, and alternative forms of protest that have emerged as Russia’s invasion of Ukraine exacerbated the authoritarian turn in Russia itself. Though heavy-handed tactics and intimidation have so far contained expressions of discontent, they have not been tested against sustained mass demonstrations should Moscow choose to tax and enlist more.

Shrinking space for protest

Putin’s latest term in office has overseen an attempt to suppress protest movements completely. Despite an intensifying crackdown on dissent, Navalny and his supporters galvanized public opposition to government repression. This led to the decapitation of his movement and ultimately to his death in state custody. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine further lowered the regime’s tolerance of opposition as now everyone is expected to march in lockstep in support of the aggression.

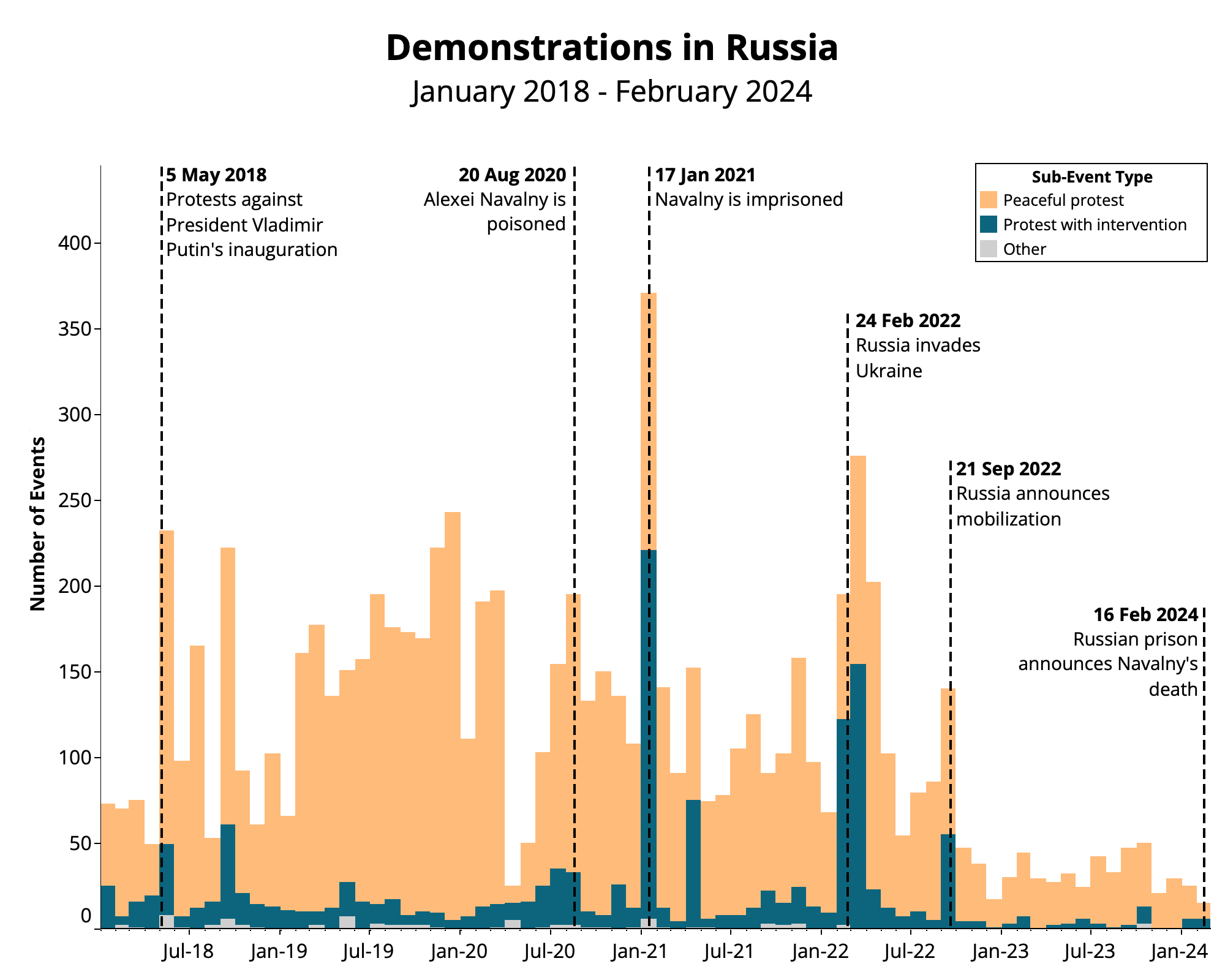

On inauguration day, 5 May 2018, Navalny’s supporters called over 90 protests across Russia that gathered from a few dozen to several hundred people. Police disrupted about a third of these demonstrations, mostly by detaining participants. The rallies were no match for the mass protests in late 2011 due to allegations of a fraudulent parliamentary election and Putin’s subsequent return to the presidency in 2012 after a pro forma stint as prime minister. Those protests were suppressed, and a crackdown on opposition ensued.2Meduza, ‘The past is a foreign country,’ 7 December 2021 In contrast, ACLED records over 350 protests against raising the retirement age in the summer and fall of 2018, most of which proceeded peacefully. Only about 15% were co-organized by Navalny’s supporters, and the rest by left-wing parties and groups.

The largest protest wave since the lull due to the COVID-19 restrictions on public gatherings — still in force and used to deny assemblies, disperse, and prosecute participants3Andrew Kramer, ‘In Russia, a Virus Lockdown Targets the Opposition,’ New York Times, 19 March 2021; Meduza, ‘Moscow authorities deny request by mobilized soldiers’ wives to hold protest, citing COVID-19 restrictions,’ 17 November 2023 — occurred in January 2021 in connection with Navalny’s return and immediate imprisonment (see graph below). In August 2020, he survived an assassination attempt with a banned military-grade nerve agent and underwent treatment in Germany. In January 2021, ACLED records 300 demonstrations against his detention, of which 200 saw police intervention. In addition, over 60 of Navalny’s associates and supporters were detained across Russia, mostly ahead of the rallies.

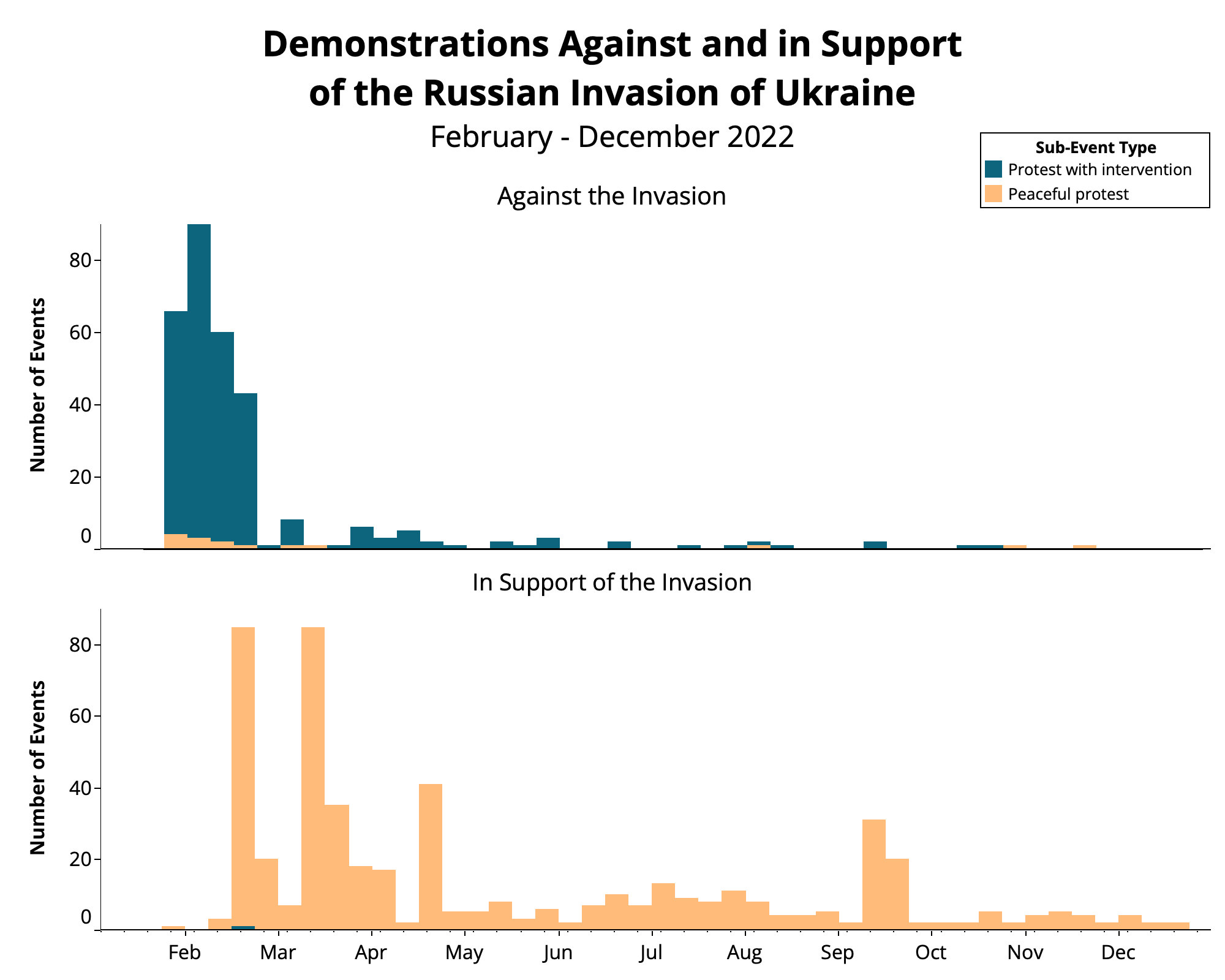

Despite the space for public expressions of discontent shrinking after the designation of Navalny structures as “extremist” in June 2021,4BBC, ‘Alexei Navalny: Moscow court outlaws ‘extremist’ organisations,’ 10 June 2021 Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in late February 2022 prompted a wave of demonstrations across Russia. These demonstrations faced the determination of the authorities to suppress dissent: Out of approximately 260 protest events against the invasion within the first month, police intervened in at least 250 of them (see graph below). Anti-invasion protests subsequently dwindled to a single-digit number of events per month as questioning the official war narrative became a criminal offense.5Human Rights Watch, ‘Russia Criminalizes Independent War Reporting, Anti-War Protests,’ 7 March 2022 Meanwhile, the government staged 270 demonstrations supporting its actions in Ukraine in March and April 2022; all but one were peaceful.

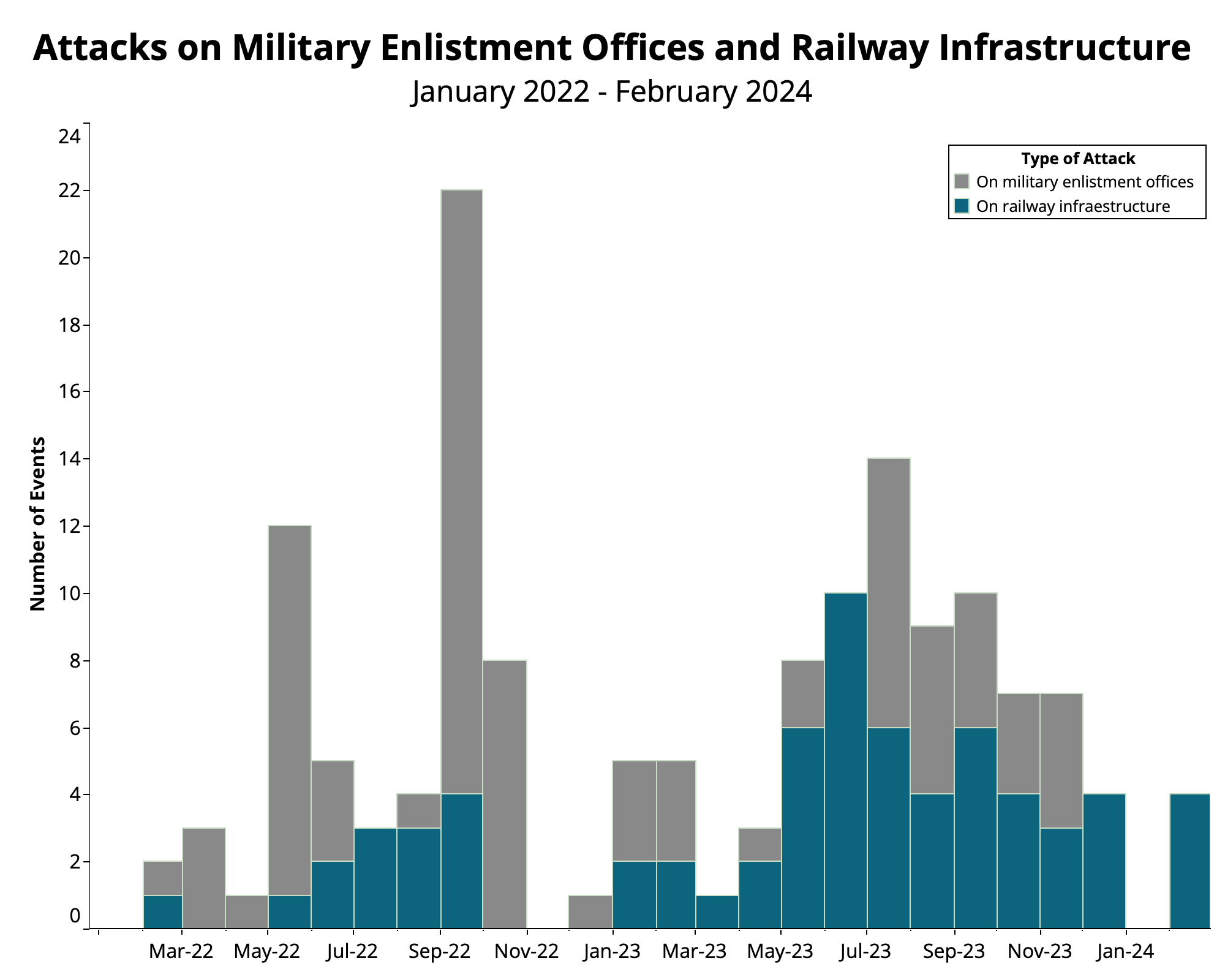

In the latest outburst of protests, the announcement of ‘partial’ mobilization on 21 September 2022 triggered close to 60 protests across Russia. Police dispersed practically all of them. Unable to voice opposition, some took to sabotaging enlistment offices and other military or dual-use infrastructure, with the phenomenon persisting to this day despite the prosecution of suspects on terrorism charges. Since early 2022, ACLED records at least 80 mostly arson attacks on military enlistment offices and over 65 instances of sabotage against railway infrastructure — the primary means of transporting personnel, equipment, and munitions to the frontline (see graph below).

Two years into Russia’s all-out war against Ukraine, the space for public dissent in Russia has shrunk dramatically. While ACLED records over 1,300 demonstration events across all 83 Russian regions in 2022, about 400 such events occurred in only 64 regions in 2023.6Excluding Ukrainian territories Russia invaded and annexed in 2014 and 2022. The crackdown affects rank-and-file (mostly online) activists7OVD-Info, ‘Overview of anti-war repression after two years of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine,’ 22 February 2024 and public figures protesting the war,8Amnesty International, ‘Russia: Anti-terrorism legislation misused to punish activist Boris Kagarlitsky,’ 13 February 2024 as well as war apologists who fail to toe the government line.9Sergey Goryashko, ‘Russia convicts Putin-critic MH17 killer for ‘inciting extremism,’ Politico, 25 January 2024 The expanding list of people and organizations designated as ‘foreign agents’10Radio Free Europe / Radio Liberty – Russian Service, ‘Putin Signs Off On Harsher ‘Foreign Agent’ Law,’ 14 July 2022 and the outlawing of any LGBTQ+ expression11Human Right Watch, ‘Russia: First Convictions Under LGBT ‘Extremist’ Ruling,’ 15 February 2024 accelerates the authoritarian turn, as does rampant indoctrination in education.12Mary Ilyushina, ‘Russia’s new history textbooks teach Putin’s alternate reality,’ 13 August 2023

Protest potential under the lid

Intensifying, though still targeted, repression13Re: Russia, ‘From war to prison: repression in Russia is becoming more ‘planned’ and harsh, but not more widespread,’ 7 February 2024 has not completely erased protest in Russia. While seemingly able to crush any perceived threat to the regime, law enforcement may be less adept at controlling information flows and acting in situations when the targets’ opposition to authorities is less obvious. Recent outbursts of street action indicate a potential for grassroots mobilization, which the authorities are struggling to contain.

A riot in Dagestan in October 2023 demonstrated the mobilization potential of non-mainstream media. Crowds descended on Makhachkala airport amid rumors of the arrival of a plane from Israel in the wake of the Gaza crisis spread on messaging apps (primarily Telegram). Police were apparently unable to discern whether the demonstration should be allowed to proceed as participants’ motivations did not challenge and rather reinforced the government’s stance amid resurgent antisemitic rhetoric.14Francesca Ebel, ‘Antisemitism charges swirl after Putin denigrates Zelensky’s Jewish roots,’ Washington Post, 25 September 2023 The law enforcement paralysis in ambiguous situations was first seen during the short-lived mutiny attempt of the Wagner Group in June.

In January 2024, protests in support of an environmental activist in Bashkortostan convicted for inciting interethnic hatred were likewise coordinated on messaging apps. While law enforcement violently suppressed the protest, killing a bystander in the process, they found no alternative to disrupting messaging apps and cellular networks to staunch the demonstrations.15Meduza, ‘Riot police clash with thousands of protesters following activist’s sentencing in Russia’s Republic of Bashkortostan,’ 17 January 2024 Unable to control information flows fully, the authorities seem to be exploring the possibility of emulating the Chinese ‘Great Firewall’ in Russia.16Mike Eckel, ‘Another Brick In The Great Kremlin Firewall: Mass Internet Outages Part Of ‘Sovereign Internet,’ Radio Free Europe / Radio Liberty, 31 January 2024 There have been at least two suspicious disruptions of the Internet and messaging apps since the start of 2024. While the first was explained by adjusting the network to prevent Ukrainian drone attacks on targets deep within Russia due to the war spillover, the most recent outage was indicative of looming changes to preclude internal mobilization and instigation from abroad.17Reuters, ‘Pre-election stress tests cause internet outages in Russia – lawmaker,’ 27 February 2024

Apart from probably poorly understanding the situation in non-ethnic Russian constituent republics, the Russian state has been grappling with the movement of the families of mobilized military personnel, who have become increasingly vocal since October 2023. Their demands evolved from replacing their men with others to stopping the war altogether. Possibly fearing a backlash from the trenches, the government is attempting to suppress protests without resorting to brute force, also by means of isolating the movement informationally and disrupting media coverage. Low-profile flower-laying ceremonies in Moscow and other cities on weekends have so far led to detentions of (mostly male) journalists covering the movement. Instead, police track down suspected activists, also with the help of facial recognition software, and intimidate them in private to dissuade protests.18Amnesty International, ‘Russia: Police target peaceful protesters identified using facial recognition technology,’ 27 April 2021 Similar tactics are now being applied to anyone turning to the streets to express discontent with the war and repression, as well as to Navalny mourners.19Meduza, ‘Moscow police reportedly ordered to ‘identify’ individuals bringing flowers to memorials honoring Navalny,’ 21 February 2024 Police have also been handing out military summonses to participating men as punishment and warning for others.20Meduza, ‘At least six St. Petersburg residents served military summonses after being arrested for leaving flowers in Navalny’s memory,’ 21 February 2024

Tightening the screws

Unlike previous elections, the 2024 vote itself is unlikely to trigger outpourings of public discontent. The likely inflated share of votes going to Putin will not trigger anything of the scale seen upon his return to the Kremlin in 2012, nor even the modest protest wave seen after his re-election in 2018. Yet the protest potential has not evaporated completely. The willingness of hundreds of thousands of Russian voters to rally around hitherto little-known but overtly anti-war challengers such as Yekaterina Duntsova, a regional journalist, and Boris Nadezhdin, a cautious liberal, can be viewed as a protest of sorts in the stifled environment. The Russian electoral commission did not allow Duntsova to run and barred Nadezhdin from the ballot after his signature-collecting campaign had drawn queues.

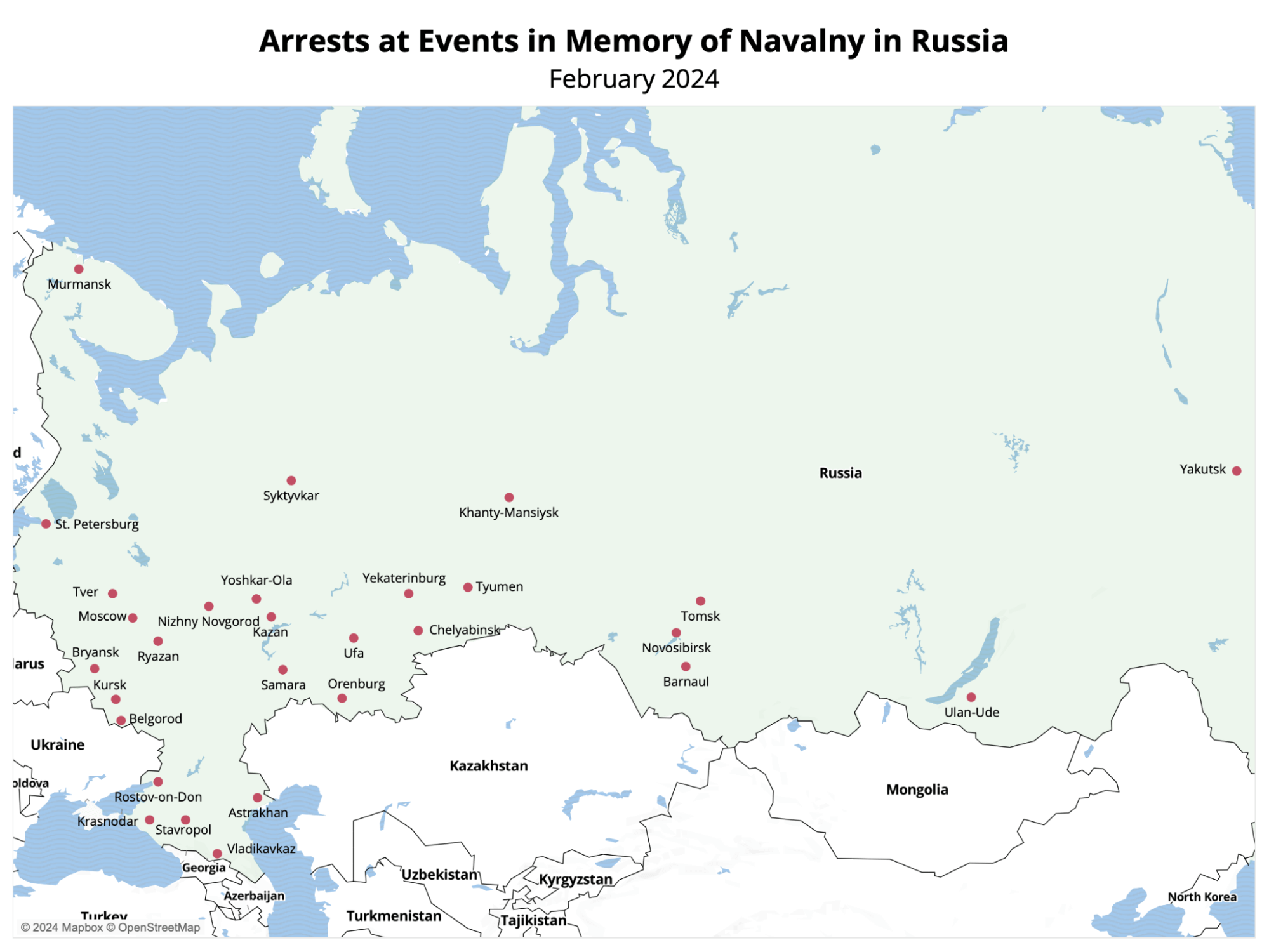

The denial of a place on the ballot to overtly anti-war candidates that enjoy visible support did not lead to street action, as the stakes for personal safety remain high. Mass arrests of grieving Navalny supporters are a case in point, as was the apparent reluctance to release his body to family and heavy policing during the funeral.21Radio Free Europe /Radio Liberty – Russian Service, ‘Navalny Buried In Moscow As Tens Of Thousands Risk Arrest To Say Farewell, 1 March 2024 The authorities have detained over 400 people turning up at landmarks commemorating victims of political repression across Russia following the announcement of Navalny’s death (see map below) and are doing their utmost to thwart any attempt to gather to commemorate Navalny and other political assassination victims.22Meduza, ‘Surveillance cameras, police patrols, and scaring students,’ 29 February 2024; Novaya Gazeta Europe, ‘Moscow authorities refuse permission for rally in memory of Navalny and Nemtsov,’ 29 February 2024

Single-person protests continue to occur despite the prospect of detention and beatings in police custody. Anti-regime and anti-war messages continue popping up in public spaces throughout the country.23Amos Chapple, ‘Writing On The Wall: The Activists Tallying Russia’s Anti-War Protests,’ Radio Free Europe /Radio Liberty,’ 19 July 2023 A protest movement in support of the jailed Khabarovsk Krai governor, Sergei Furgal, has mobilized regularly since 2020, with authorities now demanding that the movement be designated extremist to end rallies.24RBC, ‘Prosecutor demands that I/We Sergei Furgal be designated extremist,’ 7 February 2024 Unpopular policy choices after the election — increased taxation leading to falling living standards and another wave of mobilization to overwhelm Ukraine — could further test the perception of full control over the country and its people.

Visuals in this report were produced by Ana Marco