India Votes 2024: Economic Discontent Deepens Ethnic Divisions Ahead of Elections

10 April 2024

The first part of ACLED’s India Special Election Series covering the parliamentary elections held from 19 April to 1 June focuses on rising sectarian and ethnic tensions in the run-up to the polls, as economic anxieties increase the pressure on India’s caste and ethnicity-based affirmative action policies.

The existing affirmative action regime provides for quotas, popularly known as ‘reservations,’ in public sector jobs and higher education institutions for people who belong to Scheduled Castes (Dalits or SCs), Scheduled Tribes (STs), and Other Backward Classes (OBCs).1Akhilesh Pillalamarri, ‘The Future of Reservations in India,’ The Diplomat, 20 November 2022 STs also have additional land rights, with certain protectionist measures restricting the sale and ownership of tribal land to non-tribals.2Namita Wahi and Ankit Bhatia, ‘The Legal Regime and Political Economy of Land Rights Of Scheduled Tribes in the Scheduled Areas of India,’ Centre for Policy Research, 15 March 2018 These policies are aimed at addressing the historic and ongoing marginalization of these groups in the socioeconomic sphere, which is dominated by Hindu upper castes.3Akhilesh Pillalamarri, ‘The Future of Reservations in India,’ The Diplomat, 20 November 2022 Pursuant to a 1992 Supreme Court decision, the total proportion of reservations for socially disadvantaged groups cannot exceed 50%.4Akhilesh Pillalamarri, ‘The Future of Reservations in India,’ The Diplomat, 20 November 2022 In addition, people belonging to Economically Weaker Sections (EWS) — who do not fall within the categories of SCs, STs, and OBCs — are entitled to a separate 10% quota. This policy, introduced by the BJP government in 2019, was widely seen as favoring people from the historically privileged Hindu upper castes, who had hitherto been excluded from the reservations framework.5Al Jazeera, ‘Why 10% quota for “economically weak” in India has caused uproar,’ 9 November 2022

Amid a climate of economic insecurity, this system has come under increasing strain. As more communities demand reservations, the system has sparked new tensions with groups who already enjoy reservations, wary of losing their share of the pie given the fixed upper limit. In some instances, ongoing tensions have spilled over into political violence, as seen in the northeastern state of Manipur, where deadly inter-ethnic clashes triggered by the Meitei community’s demand for tribal status broke out in 2023. At the same time, some analysts and opposition politicians have criticized the upper limit itself for not being commensurate with India’s demographics, especially with regard to OBCs, whose share of quotas was decided based on projected population numbers from a 1931 census.6Shoaib Danyal, ‘Is India’s 50% cap on reservations reaching the end of its existence?,’ Scroll (India), 23 August 2021 The results of a recent caste census from the state of Bihar, where it was found that OBCs, SCs, and STs comprised around 84% of the population, indicate that the existing reservation levels may be inadequate.7Indian Express, ‘Conduct national caste census to ensure social justice: Congress,’ 2 October 2023 This has increased the clamor for such an exercise to be conducted nationwide. While the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)’s stance has been ambiguous, the Indian National Developmental Inclusive Alliance (INDIA) bloc has made a nationwide caste census and the removal of the 50% cap on reservations key planks of its campaign.8Kunal Purohit, ‘How a landmark caste census in India threatens Modi’s grip on power,’ Al Jazeera, 4 October 2023

Economic anxieties spur demands for reservations and deepen ethnic fault lines

India is among the world’s fastest-growing large economies.9John Reed and Andy Lin, ‘In charts: how India has changed under Narendra Modi,’ Financial Times, 8 January 2024 However, its economic growth has primarily been driven by industries that are not large job creators.10John Reed, ‘India’s Narendra Modi has a problem: high economic growth but few jobs,’ Financial Times, 19 March 2023 The unemployment rate has yet to fall below the pre-pandemic level, and is especially high among young people.11Forbes India, ‘Unemployment rate in India (2008 to 2024): Current rate, historical trends and more,’ 19 February 2024 Concerns over the economy and employment opportunities have seeped into the wider public consciousness. A 2023 survey by the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies (CSDS) found that more than one in three young Indians identified unemployment as the biggest problem facing the country, marking an 18 percentage point increase compared to a similar survey conducted in 2016.12Vibha Attri and Sanjay Kumar, ‘For India’s 15 to 34-yr-olds, top concern is jobs, economic struggle: What Lokniti-CSDS’s latest survey reveals,’ Indian Express, 18 August 2023 In a dramatic illustration of this, two young men breached security and stormed into Parliament in December 2023 with smoke canisters in protest against the government’s failure to address unemployment, among other issues.13Hindustan Times, ‘Parliament breach: 5th accused nabbed, all unemployed; 4 charged under UAPA,’ 14 December 2023

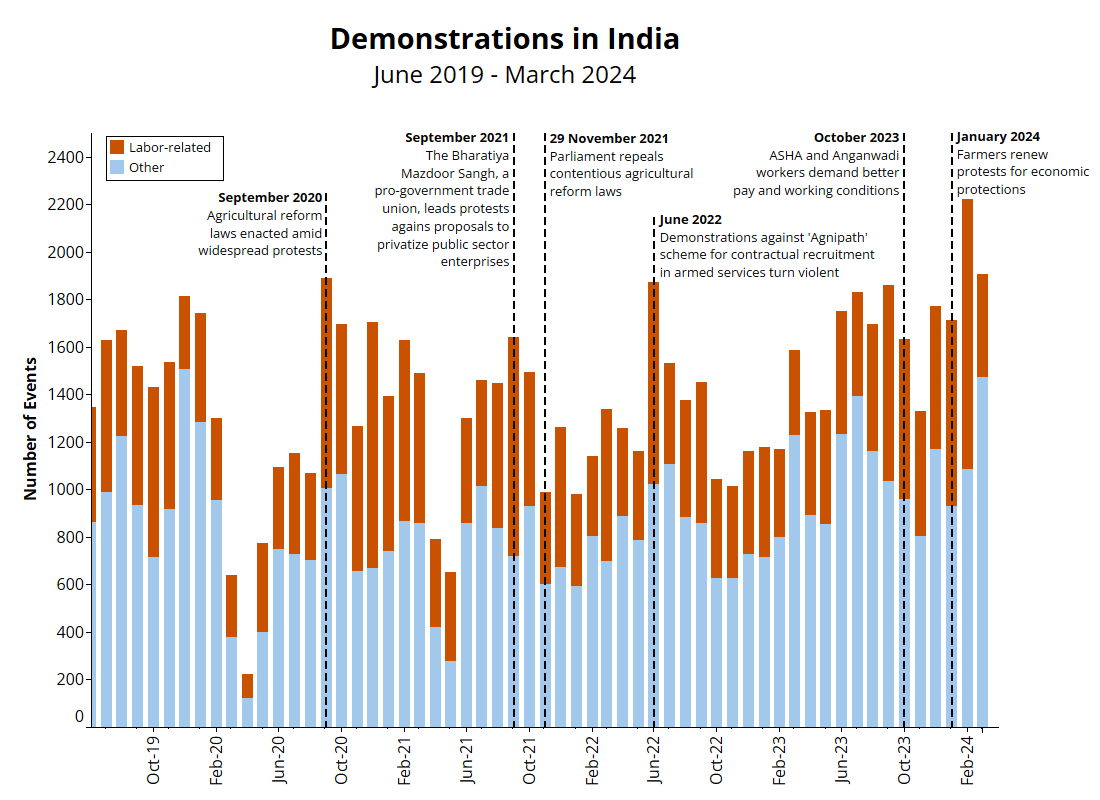

Reflecting popular discontent around the economy, ACLED data show consistently high levels of mobilization by labor groups in recent years, driving demonstration activity (see graph below). Widespread protest movements by farmers, job seekers, teachers, Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHAs), and Anganwadi workers (female community health workers) challenge narratives about the unrivaled popularity of the Modi government. In June 2022, demonstrations by youth against the Agnipath scheme, which promoted recruitment to the armed services on a short-term contractual basis, turned violent, bringing many states to a standstill.

Within the prevailing economic climate, government jobs, which offer lifelong security and post-retirement benefits, have become even more appealing. According to the 2023 CSDS survey, over 60% of young people expressed a preference for government jobs over those in the private sector.14Vibha Attri and Sanjay Kumar, ‘For India’s 15 to 34-yr-olds, top concern is jobs, economic struggle: What Lokniti-CSDS’s latest survey reveals,’ Indian Express, 18 August 2023 However, the number of such available jobs is fewer compared to the demand, with millions of applicants vying for posts numbering in the thousands.15The Economic Times, ‘Over a million apply for talathi posts in Maharashtra including engineers, PhD holders & MBAs,’ 11 August 2023 The BJP government’s ambitious targets for divestment from public sector enterprises are expected to lead to further job losses.16Umar Sofi, ‘Disinvestment of PSUs will lead to loss of quota jobs: Govt in Lok Sabha,’ Hindustan Times, 9 August 2021; Gulveen Aulakh and Rhik Kundu, ‘Govt has its eye on ₹50,000 cr kitty via divestment in FY25,’ Live Mint, 2 February 2024

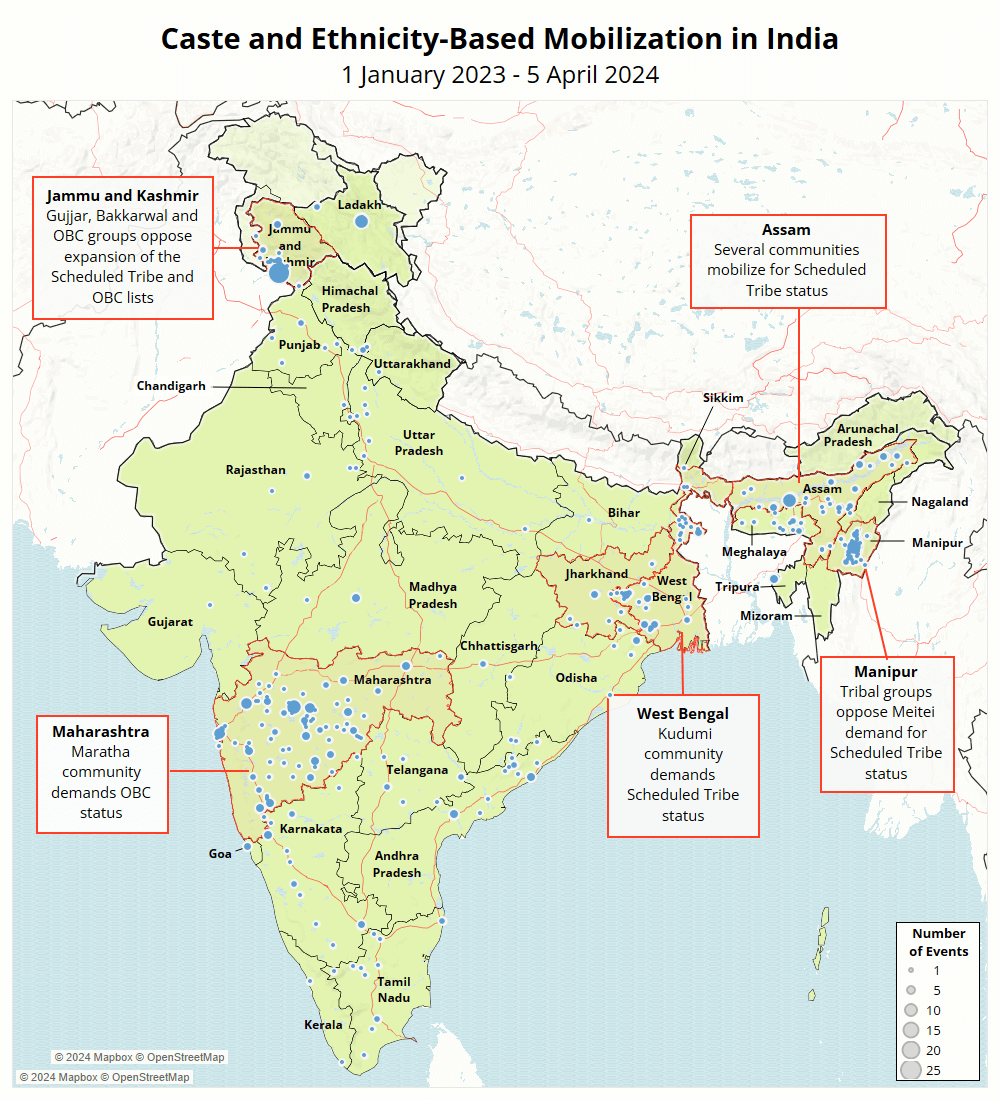

The lack of economic opportunities has, in turn, spurred demands from various communities for reservations, which would increase their chances of employment and, in the case of STs, access to resources. Between January 2023 and February 2024, ACLED data show mobilization across the country by caste and ethnic groups around reservation-related issues, with more than 50 groups staging demonstrations in 30 of India’s 36 states and union territories (see map below). In some cases, socially dominant groups, who had previously rejected classification as a marginalized group owing to perceived social stigma, have been at the forefront of demonstrations demanding reservations.17Priyanka Kakodkar, ‘How demand for Maratha quota took a dramatic turn,’ Times of India, 4 February 2024

The appeal of reservations among dominant groups is exemplified by the Maratha community’s agitation in Maharashtra, India’s richest state and the seat of its financial capital, Mumbai. Despite comprising only 30% of the population, Marathas have dominated the state’s political landscape, with 12 of its 19 Chief Ministers hailing from that community.18Priyanka Kakodkar, ‘How demand for Maratha quota took a dramatic turn,’ Times of India, 4 February 2024 Their demand for reservations is thus primarily motivated by economic considerations.

On 29 August 2023, community leader Manoj Jarange-Patil mobilized his supporters and began a ‘fast unto death,’ demanding recognition of Marathas as OBCs and ensuing entitlement to reservations under the OBC quota.19Vallabh Ozarkar, ‘Jarange Patil warns of hunger strike again, bans politicians from villages,’ Indian Express, 24 October 2024 In the following months, ACLED records over 125 pro-reservation demonstrations by the Maratha community. Although predominantly peaceful, around a third of demonstrations turned violent, with demonstrators targeting the properties of legislators they considered unsympathetic to their cause. A police crackdown on the demonstrations left several injured. The agitation also prompted counter-demonstrations by OBC communities concerned over losing opportunities if the Maratha demand were to be accepted.

Unwilling to lose political favor with either group ahead of the elections, the coalition state government, which includes the BJP, passed a law granting a separate 10% reservation in jobs and education to Socially and Educationally Backward Classes (SEBCs) within the Maratha community.20Aaratrika Bhaumik, ‘Maharashtra’s latest Maratha quota law and its challenges | Explained,’ The Hindu, 1 March 2024 However, this means the total percentage of reservations in Maharashtra now exceeds 50%. Maratha groups have rejected the new law as a political gimmick unlikely to withstand judicial scrutiny, and their demand continues to remain a trigger for further political unrest.21Aaratrika Bhaumik, ‘Maharashtra’s latest Maratha quota law and its challenges | Explained,’ The Hindu, 1 March 2024 While mobilization in Maharashtra has not, thus far, devolved into high levels of associated violence, this is not true elsewhere in the country.

Ethnic tensions spark deadly clashes in Manipur

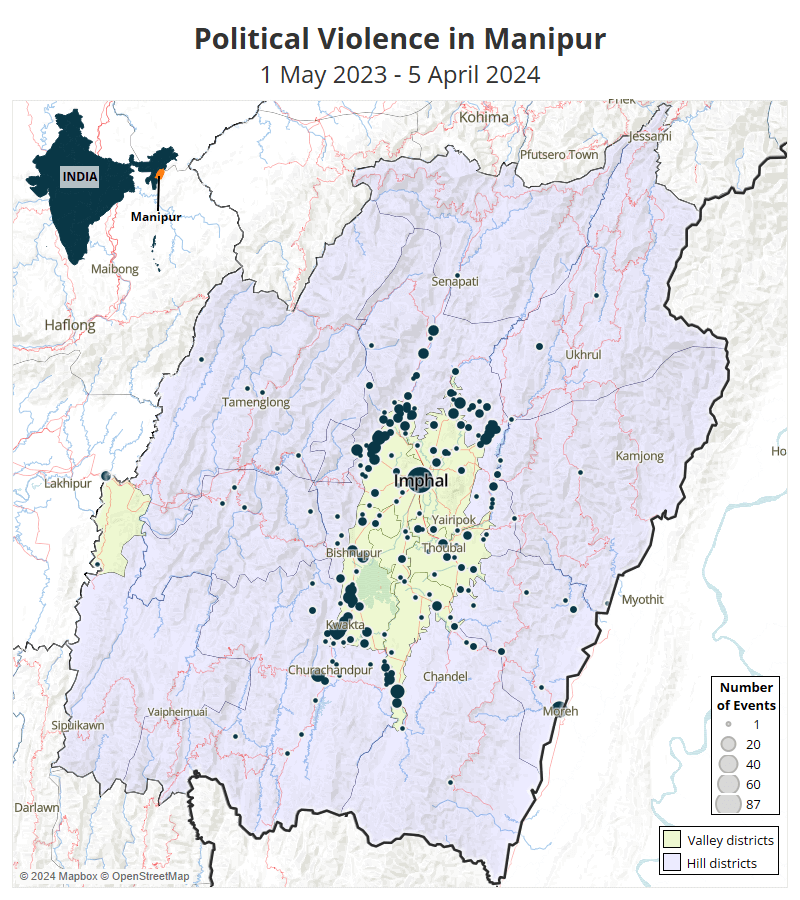

Friction among communities over reservations assumed more violent proportions in Manipur, where ongoing inter-ethnic clashes have reportedly left hundreds dead over almost a year. The trigger for the conflict was the dominant Meitei community’s demand for tribal status, which would not only entitle them to jobs under the ST quota but also allow them to buy land in the protected hilly regions, which are mainly inhabited by the Kuki and Naga tribes.22Sukrita Baruah, ‘Meitei ST demand in Manipur gets HC boost, touches another raw tribal nerve in NE,’ Indian Express, 28 April 2023 With land being an important resource in Manipur’s agrarian-dependent economy, tribal groups, many of whom practice shifting cultivation on the hills, oppose this demand.23Suryagni Roy, ‘Agriculture and trading: Amid violence, backbone of Manipur’s economy takes a blow,’ India Today, 11 August 2023; Rakhi Bose, ‘Why Kuki-Meitei Conflict In Manipur Is More Than Just An Ethnic Clash,’ Outlook, 29 May 2023 The demand for reservations has worsened existing divisions between the communities on issues of identity. The Meiteis, most of whom follow Hinduism, have long claimed that they are the real Indigenous peoples of Manipur, castigating the mainly Christian Kukis as outsiders from Myanmar.24Soutik Biswas, ‘Manipur: Fears grow over Indian state on brink of civil war,’ BBC, 22 June 2023; Karishma Hasnat, ‘Flow of refugees from Myanmar reignites ethnic strains in insurgency-battered Manipur,’ The Print, 15 March 2023

Tensions spilled over on 3 May 2023, when the two groups clashed in Churachandpur district during a ‘Tribal Solidarity March’ opposing reservations for Meiteis. The violence quickly spread to other parts of the state, with ethnic mobs running rampage and burning down entire villages. Imphal and Churachandpur cities, the hubs of Meitei and Kuki communities, respectively, saw much of the violence at the beginning of the conflict. Ten months in, violence in the region continues at a high level, and the involvement of militants on both sides and mobs’ widespread looting of arms are further fuelling the conflict.25Aakash Hassan and Hannah Ellis-Petersen, ‘“Foreigners on our own land”: ethnic clashes threaten to push India’s Manipur state into civil war,’ The Guardian, 9 July 2023 Most of the fighting is now concentrated in the peripheral areas between the hill and valley districts, where the Kuki and Meitei communities live in almost complete segregation after large-scale displacements due to the conflict (see map below).26BBC, ‘Manipur: Murders and mayhem tearing apart an Indian state,’ 13 July 2023

Despite heading both the central and state governments, the BJP has struggled to restore peace, as both communities remain steadfast in their demands. Ethnic allegiances have gained primacy over other considerations among the political class, making it difficult to arrive at a consensus.27Deeptiman Tiwary, ‘Decode Politics: Who are Arambai Tenggol, the group at whose beckoning Manipur Meitei MLAs came rushing,’ The Indian Express, 27 January 2024; The Wire, ‘“Imphal Out of Bounds for Kuki-Zos,” 10 MLAs Urge PM to Create DGP, Chief Secy Posts for Hills,’ 17 August 2023 In January, Manipur’s Chief Minister, a Meitei strongman, endorsed an armed Meitei militia’s charter of demands, which, among other things, called for the delisting of “Kuki illegal immigrants” as STs.28The Hindu, ‘Meitei group sets peace terms for Manipur Chief Minister, MLAs,’ 24 January 2024; Deeptiman Tiwary, ‘Decode Politics: Who are Arambai Tenggol, the group at whose beckoning Manipur Meitei MLAs came rushing,’ The Indian Express, 27 January 2024 That he continues to hold office has been interpreted by some as an unwillingness by the BJP to antagonize the Meitei community, which forms a part of the BJP’s core Hindu vote bank, ahead of the elections.29D.K. Singh, ‘Why won’t Modi axe Manipur CM Biren Singh? 4 reasons why he won’t & 5 reasons why he must,’ The Print, 24 July 2023; John Simte and Angshuman Choudhury, ‘Arambai’s Political Sway Is Not Only in Imphal but Far Beyond It. Yet the State Turns a Blind Eye,’ The Wire, 11 February 2024; Rokibuz Zaman, ‘Why Biren Singh stays as Manipur chief minister despite even BJP leaders asking for his ouster,’ Scroll (India), 29 June 2023

Mandal vs. Mandir 2.0

Caste and community linkages play a major role in determining voting patterns in India, with all political parties vying for the support of the dominant groups. Ahead of the elections, ethnic groups may intensify agitations over reservations as they seek to gain concessions by capitalizing on their electoral importance. When faced with competing demands by multiple dominant communities, political parties may prefer not to make a difficult choice.

In the case of Manipur, this means that the current deadlock is likely to continue. Further complicating the democratic exercise is the increase in the relative strength of armed insurgents, who have a history of interfering in elections, as a result of the conflict.30Binalakshmi Nepram and Brigitta W. Schuchert, ‘Understanding India’s Manipur Conflict and Its Geopolitical Implications,’ United States Institute of Peace, 2 June 2023; Ananya Bhardwaj, ‘Recruitment spikes across insurgent outfits in Manipur, “more than when insurgency was at its peak”’, The Print, 31 January 2024 Mass displacements and segregation among the warring communities have also necessitated special voting arrangements, including phased voting and polling stations set up in relief camps.31Sukrita Baruah, ‘In Manipur, two-phase polling for two LS seats; special booths for displaced voters,’ Indian Express, 17 March 2024

Meanwhile, under Modi — himself an OBC — the BJP, which has traditionally been the party of upper-caste Hindus, has managed to gain the support of diverse groups within the caste hierarchy by championing the cause of Hindu nationalism, where caste identities play second fiddle to religion.32Milan Vaishnav, ‘Decoding India’s 2024 Election Contest,’ Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 7 December 2023; Kunal Purohit, ‘How a landmark caste census in India threatens Modi’s grip on power,’ Al Jazeera, 4 October 2023 However, as seen by its response to the crises in Maharashtra and Manipur, the party remains captive to caste and ethnic politics. Sensing an opportunity, the INDIA bloc hopes to make inroads into the BJP’s vote bank and reclaim support among socially disadvantaged groups, by advocating for a caste census and a revamp of the reservations system.33Kunal Purohit, ‘How a landmark caste census in India threatens Modi’s grip on power,’ Al Jazeera, 4 October 2023 Amid popular anxieties about the economy and employment, their call may resonate with the wider public.

This tactic has found success in the past, when the opposition’s so-called Mandal politics triumphed over the BJP’s Mandir (temple) movement. In the 1990s, the BJP led a nationwide movement to build a temple at the supposed birthplace of Lord Ram in Ayodhya, culminating with a Hindu mob demolishing the mosque that stood on the site.34Hannah Ellis-Petersen and Aakash Hassan, ‘Modi inaugurates Hindu temple on site of razed mosque in India,’ The Guardian, 22 January 2024 The opposition, then led by the Janata Dal and other regional parties, countered by introducing reservations for OBCs — the largest socio-political bloc in India — as recommended by the Mandal Commission, a body formed to examine the conditions of SEBCs.35Vasudha Mukherjee, ‘The Mandal Commission decoded: How OBC reservation came into effect,’ Business Standard, 20 October 2023 The opposition’s gambit reaped greater electoral benefits.36Kunal Purohit, ‘How a landmark caste census in India threatens Modi’s grip on power,’ Al Jazeera, 4 October 2023

While the BJP in 2024 appears to be in a stronger position than in the 1990s, a vote on the economy, harnessing ethnic discontent, is perhaps the opposition’s best bet to challenge the BJP’s Hindu-first strategy.

Visuals in this report were produced by Ana Marco