Between violence, geopolitical competition, and the quest for social justice: Chad’s road to elections

30 April 2024

Following three years of transitional government since President Idriss Déby’s assassination, Chad will hold presidential elections on 6 May amid tight political controls by the incumbent leader. In this guest contribution, Dr. Valerio Colosio examines political violence in Chad through two generations of Déby rule and whether the election will confirm the status quo or trigger some deeper transformations, in a moment of big geopolitical changes in the Sahel.

On 28 February 2024, Chadian security forces fired on the headquarters of the opposition Socialist Party Without Borders in the center of Chad’s capital, N’Djamena, killing four people, including its leader, Yaya Dillo. Authorities say Dillo was behind an attack on the National Security Agency, a charge denied by party officials.1Mayeni Jones and Wedaeli Chibelushi, ‘Yaya Dillo: Chad opposition leader killed in shootout,’ BBC, 29 February 2024 Dillo was one of the challengers to incumbent transitional President Mahamat Idriss Déby Itno in the forthcoming elections, and exactly three years earlier, security forces killed his mother and two of his children in an attack on his home while he was a presidential candidate against then-President Idriss Déby Itno, Mahamat Déby’s father. Idriss Déby won that election, only to be assassinated shortly afterward, on 20 April 2021. Following his death, Mahamat Déby, then an army general, suspended the constitution and took over the leadership of the newly created Transitional Military Council, promising an 18-month transition to a new democratic government. The months of transition dragged on, and Mahamat Déby’s initial promise not to stand in the elections was broken, but on 6 May 2024, Chadians will again vote for a president, having approved the country’s fifth constitution in a referendum on 17 December 2023. Most observers expect Mahamat Déby to be confirmed as president in elections heavily controlled by the incumbent government.

Chad is a country of more than 17 million people, straddling the Sahara desert, the Sahel, and the savannas of central Africa and surrounded by conflict hotbeds in Libya, Sudan, the Central African Republic, and the Lake Chad region. The country suffers from deep-seated problems, including the poor state of infrastructure, domestic tensions, and a difficult inter-ethnic coexistence in a predominantly arid territory. Chadian history is often intertwined with violence. Dillo and Idriss Déby are two of the many politicians to have died in violent circumstances, while the country has not seen a peaceful transfer of power since the assassination of its first president, Francois Ngarta Tombalbaye, in 1975. The French colonial government, which had united a vast and heterogeneous territory under a single nation for its strategic needs, violently repressed any forms of dissent and applied what scholars defined as “indigénat”:2Gregory Mann, ‘What was the Indigénat? The ‘Empire of law’ in French West Africa,’ The Journal of African History, 50(3), 2009, pp. 331-353 a fragmented administrative system aimed at creating competition between different ethnic groups and encouraging rivalries between the mainly Muslim herders and traders of the north and the animist and Christian farmers of the south.3Ladiba Gondeu, ‘Notes sur la sociologie politique du Tchad,’ Sahel Research Group, October 2013

Chad’s endemic instability

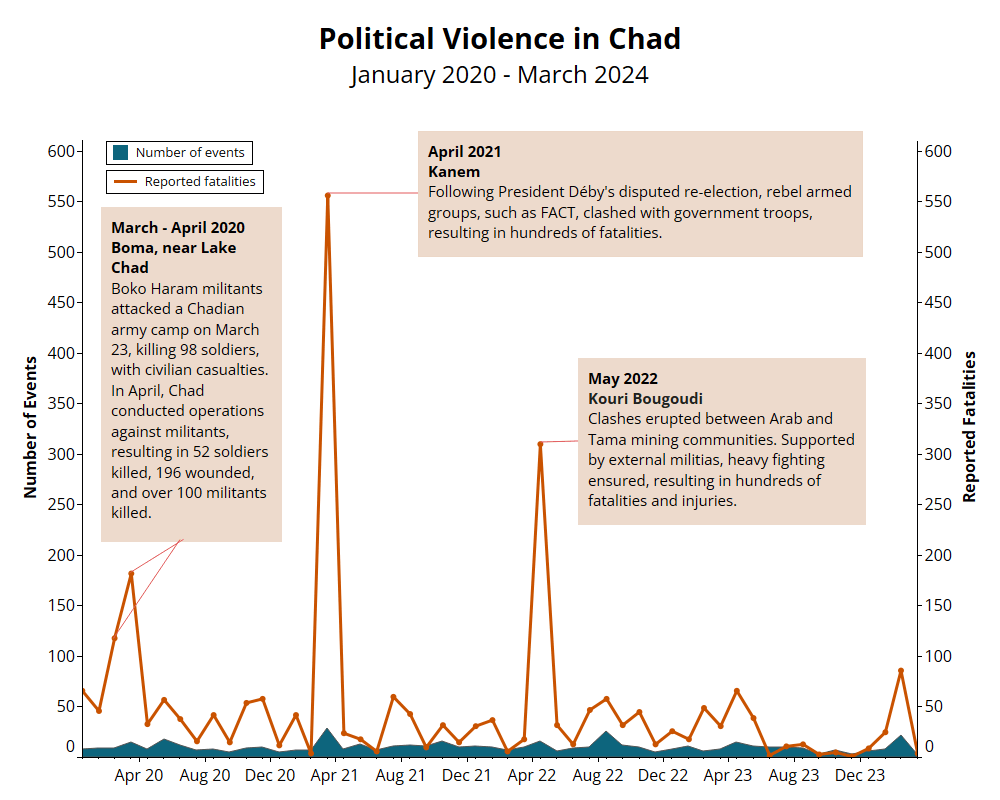

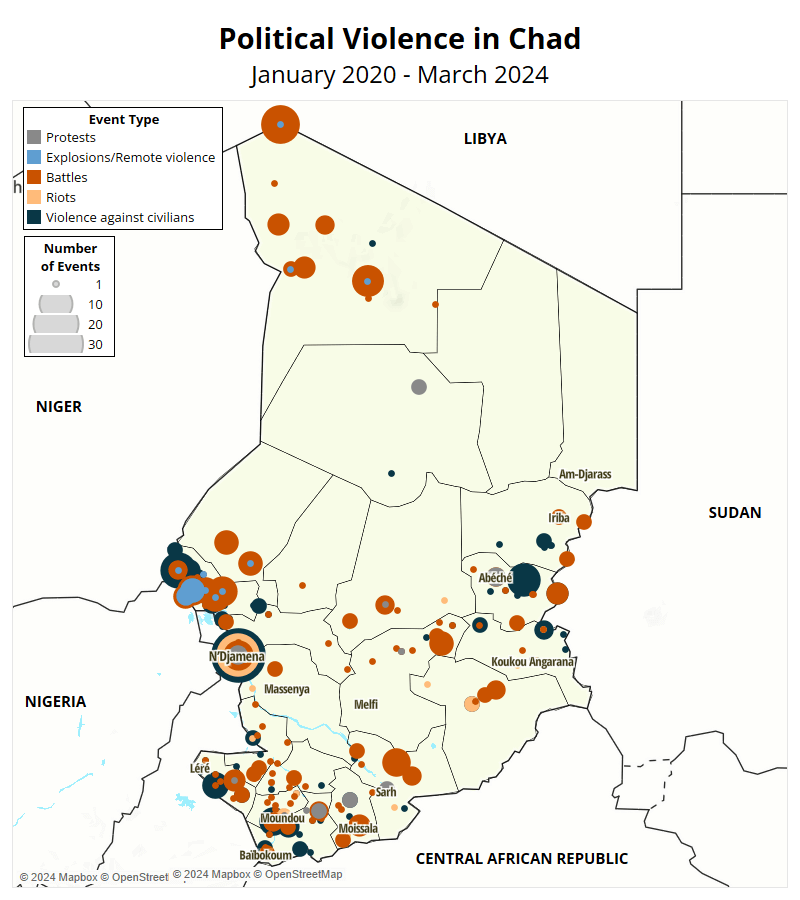

The legacies of colonial indigénat have survived to this day, and violence is one of the fundamental elements of local governance and territorial control. Between January 2022 and March 2024, ACLED records nearly 270 political violence events, which resulted in the reported deaths of over 1,025 people (see graph below). Another 822 conflict-related fatalities were reported in 2021, one of the most turbulent years in Chad’s recent history. While most violence is limited in scope, with small-scale clashes involving armed ethnic and communal militias, rebel and jihadist activity have claimed hundreds of lives. A Boko Haram attack on the Chadian army in Boma, on Lake Chad’s shores, caused the deaths of 98 soldiers in March 2020. Clashes with rebel groups — the main one being the Front pour l’Alternance et la Concorde au Tchad (FACT) — have killed no fewer than 400 people since 2021. Yet, the state is also responsible for the violent repression of peaceful protests, including the events of October 2022, when at least 73 protesters denouncing the unlawful extension of presidential rule were killed at the hands of the army.

The United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA) publishes biannual reports on “communal conflicts” — a term used to describe clashes between different local groups — which confirm these figures.4UNOCHA, ‘Tchad: Aperçu des conflits inter/intracommunautaires,’ January 2024 These reports focus on the immediate causes of these incidents, such as poor governance of local resources. But many scholars and activists agree that violence in Chad has deeper roots. The communal conflicts that often pit livelihood groups (e.g.herders, farmers) or different ethnic groups against each other for access to land or water; the rarer but more brutal battles between armed factions such as FACT on the border with Libya and smaller rebel movements in the areas bordering Sudan and the Central African Republic; the jihadist insurgency of Boko Haram in the Lake Chad region; and the harsher repression of any form of dissent in urban centers: they all share a common matrix.

French researcher Marielle Debos coined the term “interwar” to define the period of stability under Idriss Déby from December 1990,5Marielle Debos, ‘Living by the Gun in Chad: Combatants, Impunity and State Formation,’ Bloomsbury, 15 October 2016 when he overthrew his predecessor Hissène Habré in a coup. Doing so, Idriss Déby put an end to the civil war that had begun in the 1970s, began to exploit the country’s oil resources, and modernized the transport and communications infrastructure. However, improvements in access to education, health, water, and electricity have been lackluster and job opportunities for the youth scarce; political reforms remained elusive. Idriss Déby did not seek to include the diverse social and political actors as stated in the 1996 constitution — the first to formally recognize a multi-party and decentralized system — but rather ensured his clan’s survival in power through a complex game of balancing and co-opting local power brokers (Déby was a member of the Bidayat clan of the Zaghawa ethnic group).

In Chad, the stability of a central state with little capacity to provide services and control the territory relies on the support of influential and often armed subnational elites able to maintain order at the local level. This system has a strong continuity with the colonial system when the French ruled through a light but authoritarian administration focused on repressing and exploiting colonial subjects. Idriss Déby combined this authoritarian structure with the reforms promised in the constitution to strengthen the state’s capacity to control the territory. The National Assembly was last elected in 2011 and has not since been renewed, with much of the power in the hands of the president and the executive. Despite the creation of decentralized authorities, only 42 municipal councils were elected in 2012, while all other levels of local authority are appointed by the president and are often soldiers or former rebels. In rural areas, Idriss Déby’s administration appointed loyalists to the head of customary chiefdoms while increasing the number of cantons from 446 in 1996 to 719 in 2021.6Valerio Colosio, ‘(Re)naming the Cantons, Re-exerting Authority: Ambiguous Decentralization Reforms and the Nature of Power in Rural Chad,’ Africa Today, 68 (3), 2022, pp. 3-23

In fact, ethnographic research in the north7Julien Brachet and Judith Scheele, “A ‘despicable shambles’: Labour, property and status in Faya-Largeau, Northern Chad,” Africa, 86 (1), 2016, pp. 122-141 and center8Valerio Colosio, ‘(Re)naming the Cantons, Re-exerting Authority: Ambiguous Decentralization Reforms and the Nature of Power in Rural Chad,’ Africa Today, 68 (3), 2022, pp. 3-23 of the country, as well as in the Lake Chad region,9Alessio Iocchi, ‘Living through Crisis by Lake Chad: Violence, Labor and Resources,’ Routledge, 13 July 2022 reveals how local power is exercised through strongmen who compete with each other for support and resources, with government officials acting mainly as mediators. The state maintains its presence by managing these complex networks of patronage, allowing a degree of violence among its clients as a means of control and heavily repressing any forms of dissent. These methods have provided relative stability, but at the same time, they have exacerbated internal tensions, fuelled communal conflicts (especially in the less arid southern and central regions), and facilitated the infiltration of armed groups into certain areas of Lake Chad or the Libyan and Sudanese borders (see map below).

Déby’s rule in Chad and the 2024 election

Despite its fragility, Chad’s regime has survived multiple crises. Idriss Déby was killed in 2021 on the front line after FACT marched from Libya toward N’Djamena. The FACT challenged the Chadian government twice — in 2019 and 2021 — but the superiority of the French-backed Chadian army prevented it from gaining ground. Similarly, after bombing N’Djamena twice in 2015 and ambushing the army in Boma in 2020, Boko Haram did not carry out any other major actions on Chadian territory and remained active as a small-scale insurgency in the west of the country, severely affecting the livelihoods of local farmers and fishermen but not directly threatening the central government. In 2022, most of the smaller rebel groups agreed to support the transitional government upon signing the Doha accord. As a result, the current level of direct external threats to the government, which will be elected in May, appears lower than in 2021.

However, growing geopolitical competition and the uncertain economic outlook due to the volatility of crucial oil revenues could revive internal divisions. Even small-scale communal conflicts have the potential to trigger wider tensions and spill over into international dynamics. In the Nya Pende department, tit-for-tat killings between livelihood groups (e.g. herders and farmers) across the border with CAR led to nearly 30 deaths in May 2023 in the same area where, two years earlier, six Chadian soldiers were killed in unclear circumstances by Russian-backed soldiers from CAR.10Le Monde, ‘Le Tchad accuse l’armée centrafricaine d’avoir tué six de ses soldats, dont cinq auraient été « exécutés »,’ 31 May 2021 Similar incidents in other unstable borders and simmering tensions over refugee influxes from neighboring CAR and Sudan have the potential to involve external powers and escalate.

In the last three years, military coups overthrew the governments in Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger, where France had an important military presence to conduct anti-terrorism operations. While Mahamat Déby is a staunch ally of France and maintains good relations with other Western actors, he has also courted the support of the Gulf States, China, and Turkey, while his visit to Moscow in January 2024 shows his desire to maintain dialogue with all potential partners.11Mathieu Olivier, ‘Behind the scenes of Chad’s strategic rapprochement with Russia,’ The Africa Report, 29 January 2024

In the meantime, Chad’s president is also trying to find a new balance in internal affairs. The new constitution, approved in December 2023, restored the role of the prime minister and formally gave more independence to the judiciary and legislature, whose prerogatives were eroded by Déby’s father. The appointment of Succès Masra — one of the main organizers of the October 2022 demonstrations, popular among the youths and the southerners — as prime minister and the creation of a ‘National Commission for Peace, National Reconciliation, and Social Cohesion’ suggests an attempt by the president to pacify the country.

These actions are reminiscent of Idriss Déby’s cosmetic reforms in 1996 and are unlikely to produce radical change.12Remadji Hoinathy and Yamingué Bétinbaye, ‘Chad two years later: little progress, plenty to worry about,’ Institute for Security Studies (ISS) Africa, 4 May 2023 The army and other strategic public-owned companies remain in the hands of the same inner circle close to the president, consisting mainly of quarrelsome13David Lewis, ‘Yaya Dillo: What does killing mean for Chad and its ruling elite?, Reuters, 1 March 2024 elites from the north of the country. While Mahamat Déby’s regime does not seem willing to enhance its inclusiveness, the focus of France and other Western countries on ‘stability’ could eventually backfire, as the lack of support for democratic institutions and social equality is likely to create resentment among the population as seen in other Sahelian countries.14Cyril Bensimon, ‘Remadji Hoinathy: “In Chad, France doesn’t seem to understand anything other than preserving stability”’ Le Monde, 7 January 2023 In recent years, Chad’s youth displayed a high propensity to mobilization and activism despite remaining largely excluded from political and economic life,15Carole Assignon and Etienne Gatanazi, ‘Tchad : les raisons de la colère des jeunes,’ Deutsche Welle, 21 October 2022 and there is a widespread demand for greater transparency and inclusion in state management.16Gondeu Ladiba, ‘Chad’s Political Transition Might Be Its Last Shot for Democracy and Peace,’ United States Institute of Peace, 6 July 2023

The Sahelian states face structural problems that require a radical overhaul of a colonial-inherited institutional framework and a partnership with the West based mainly on providing stability through military support. In Chad, regional competition and domestic pressure are already upsetting the existing balance, and it is unclear whether and how the upcoming elections and institutional reforms will be enough to preserve the actual political setting. All around Chad, regional powers, including Russia and the United Arab Emirates, have challenged France’s decades-long hegemony in the region, while domestically there is an increasing uneasiness with the former colonial power’s influence on their country’s political life and with a West-backed political elite unable or unwilling to improve the livelihood of its citizens. Exclusive attention on stability promotion — nevertheless ineffective, as shown by the data on widespread violence in the country — at the expense of democracy and social justice may indeed backfire and generate calls for radical change, which Mahamat Déby, grappling with an unstable network of allies at home and a turbulent regional environment, may struggle to sustain.

The forthcoming election may not be a decisive turning point in Chad’s history but may provide indications as to whether Chad may soon follow the trajectory of Burkina Faso, Niger, and Mali or look for alternative paths through the unchartered waters the Sahel region is starting to navigate.

Visuals in this report were produced by Ana Marco