Q&A with

Nohad Eltayeb and Ali Mahmoud Ali

ACLED Executive Research Assistant and Sudan Researcher

Sudan’s one-year-old civil war has killed thousands of people, displaced millions, and splintered the country into a mosaic of rival militias. Neither of the two main warring parties, the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), appears able to win or reunite the country of 45 million people. In this Q&A, two of ACLED’s Sudanese researchers, Nohad Eltayeb and Ali Mahmoud Ali, reflect on the continuing seesaw of battles, the viability of possible new US-led peace talks, and their own fading hopes for what just five years ago seemed like a bright new beginning for the country.

Your recent report One Year of War in Sudan gave insights into the conflict from ACLED’s data, which you helped collect. In those first 12 months, ACLED has now counted at least 15,830 people killed, tracked a tripling of the number of rival militias, and calculated that half of the fighting and civilian deaths happened in Khartoum. How did the civil war start for you personally?

NOHAD: April 15th, 2023 was one week before Eid al-Fitr [a big holiday at the end of Ramadan, the Muslim holy month of dawn-to-dusk fasting]. Many members of my family who live abroad had come home. Most houses in Khartoum were getting prepared to celebrate. That Saturday, we woke up to hear gunshots and explosions.

Our immediate assumption was: “This is a military coup.” In recent years, it wasn’t very uncommon to wake up with sounds like that. But when we switched on the TV and looked at social media, people were saying that battles broke out in the city between the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and Rapid Support Forces (RSF). Even then nobody expected that fighting would come into Khartoum. They thought it was a local clash, that they’d fight in less-populated areas.

We found ourselves in one of the first main battlefields. Our house is in the center near the airport, and the RSF quickly occupied our area, living in people’s houses. They looted shops for food and malls for booty. Every half-hour, we’d hear airstrikes and artillery shelling, very close. Bullets hit the walls and made holes. Everyone adapted to the situation by moving away from windows and going to the middle areas of the apartment. Luckily, because everyone had come for Eid, many homes like ours had extra stocks of food to see us through. But we couldn’t really leave or do anything outside. Supermarkets weren’t open. There was no food, no power, sometimes no water. Central Khartoum was clearly not inhabitable anymore.

Young people like me wanted to just leave, but taking the decision as a family was really hard. We couldn’t tell whether it was going to go on or end in a few weeks. And after the airport closed down on the first day, the only way out was buses going to nearby states or to Egypt or Ethiopia. People like my parents were very against leaving. They’d ask, “What are we going to do abroad? It’s hard to start over.”

It was very difficult to get a bus ticket to Egypt. The price went up from 100 US dollars per person to $400. We heard that people were stuck at the Egyptian border for days in buses in a hot desert. My brother, his wife, and their small child managed to get to Port Sudan on the Red Sea coast, then to Jeddah, and then back home to Germany. By the time we persuaded my parents to move, 10 days had gone by. We decided to head for Ethiopia, where another of my brothers lives. The road south was filled with RSF checkpoints. They were very young, like child soldiers. Again, we were lucky. In those first days they weren’t focused on looting, but we took the precaution of giving all the valuables to the women. I had my passport and a few hundred US dollars in cash. They usually only searched the men.

At the border we walked over a bridge, got a visa, and entered the Ethiopian town of Metema. There were many refugees. There weren’t yet many humanitarian organizations. It was dark and it felt dangerous. We stayed another difficult night there. The next day we found a bus to the town of Gondar, 200 kilometers further on. From there we could fly to Addis Ababa.

ALI: I was already working with ACLED before the war, reporting back data on violent incidents around Sudan. Back in those days everyone was watching the ‘workshops’ between the various political and military factions that were supposed to restore the transitional government and find a peaceful way forward for the country. But something abnormal was happening in the months before April. In Darfur, the SAF and RSF began not to coordinate. There were assassinations of officers. Whenever I shared with my friends my concerns that there could be a war, they told me that I was getting scared too easily. So I convinced myself to calm down.

But it wasn’t just about being exposed to the data about violence every day. The whole political situation didn’t look stable. Security measures — which originally were imposed to deter the protesters — were implemented even on days when no calls for demonstrations were made. Bridges across the Nile were closed. Tanks were deployed near the presidential palace. Roads leading to the SAF general headquarters were blocked.

In the end, it seemed so clear to me that a war could erupt at any time. I told my brother who lives in Saudi Arabia that we had to move the family there for a while. There were many reasons to do so. My mother is not mobile — she would find travel hard if there was trouble — so we convinced my parents to go to Saudi for Ramadan. I went to the United Arab Emirates. When the war broke out, only one sister was left. So we were very lucky.

In the four years after April 2019, after the armed forces ousted President Omar al-Bashir, had you noticed any long-term signs that the transitional government was doomed?

NOHAD: Not always. Some people were hopeful after the appointment of the very first transitional government, but the power-sharing deal between the military and the civilians was opposed by many, and seen as a potential setback in the path of democratic transition. I was active and very involved in politics in general. I went to demonstrations, protests, and all the sit-ins outside the SAF headquarters. In Sudan, previous revolutions started in the streets. We thought that’s how coups happen: You convince the army that the president is no good!

The Sudanese people were inspired by the Arab Spring. But what drove people in April 2019 was mainly economic — the price of bread and fuel. I was motivated by many other things, too. The Bashir regime had been in power for 30 years. It was Islamist, totalitarian, corrupt, and against human rights. It stirred up conflicts in provincial areas like Kordofan, Blue Nile, and of course Darfur. At the protests, we had many women and young people. Women in particular had a tough time with that regime. Police could arrest you for just how you looked. As a government, it wasn’t working.

Still, before 2019, you wouldn’t see as many soldiers in Khartoum. Afterward, we got used to a lot of different military uniforms! RSF soldiers were successful in embedding themselves in Khartoum. Looking back at it, everyone expected that there would be trouble in general but — partly because there was an internationally backed process to lay the basis of a new government — nobody thought they’d be that ambitious to start fighting in Khartoum, the capital and most populous city.

ALI: I was a protester, too. Most of the youth were part of it. I wasn’t part of any political party. I went with all my friends, to protect ourselves from the security forces. We didn’t have any ‘model’ that we were aiming for. We just had high hopes for Sudan to be a better place. We thought anything would be better than Bashir’s regime.

A banner carried through the center of Khartoum, Sudan, on 15 April 2019 by supporters of the revolution against former President Omar al-Bashir. Photo: Ali Mahmoud Ali/ACLED.

Nobody imagined it would end like this. Our scenario was that either we go to democracy or back to dictatorship. What happened in Tunis in the Arab Spring was our hope; what happened in Egypt was our fear. The terrible wars in Yemen, Syria, Libya seemed far away. Remember, in Sudan protesters were peaceful on the streets, even if they were oppressed by security forces. The whole opposition was under one umbrella. There had been wars in the provinces, but the rebel groups didn’t have the capacity to take war to the whole country. We didn’t expect the president’s bodyguards to do this. Nobody expected the RSF to attack the SAF.

Ironically, former President Bashir did predict that chaos would follow if he left power. It seems like there are forces who wanted it to happen that way.

Are there any political forces that offer hope for Sudan today?

ALI: All the political parties and figures are irrelevant. Nobody has any power to mediate between the main two rivals, the SAF and RSF. The divisions remain deep: The RSF is fighting not just against the west of the country but the central and northern tribes that traditionally control the government.

Taqaddum [The Sudanese Coordination of Civil Democratic Forces, led by former Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok] has some legitimacy with the international community. Theoretically it’s the same alliance of Forces of Freedom and Change. But they took over the 2019 revolution, and, since they became part of the transitional government, they neglected many things, including the revolution’s goals. They just replaced Bashir’s National Congress Party. They allied with the security forces who killed hundreds of protestors; now they seem to be with the RSF, and they criticize them less than the SAF.

The only political party that seemed somehow neutral is the Sudanese Communist Party, but that also doesn’t have so much influence. It’s only popular with unions, students, and state employees. It was always negative about the transitional government negotiations and withdrew from the alliance of forces for freedom and change.

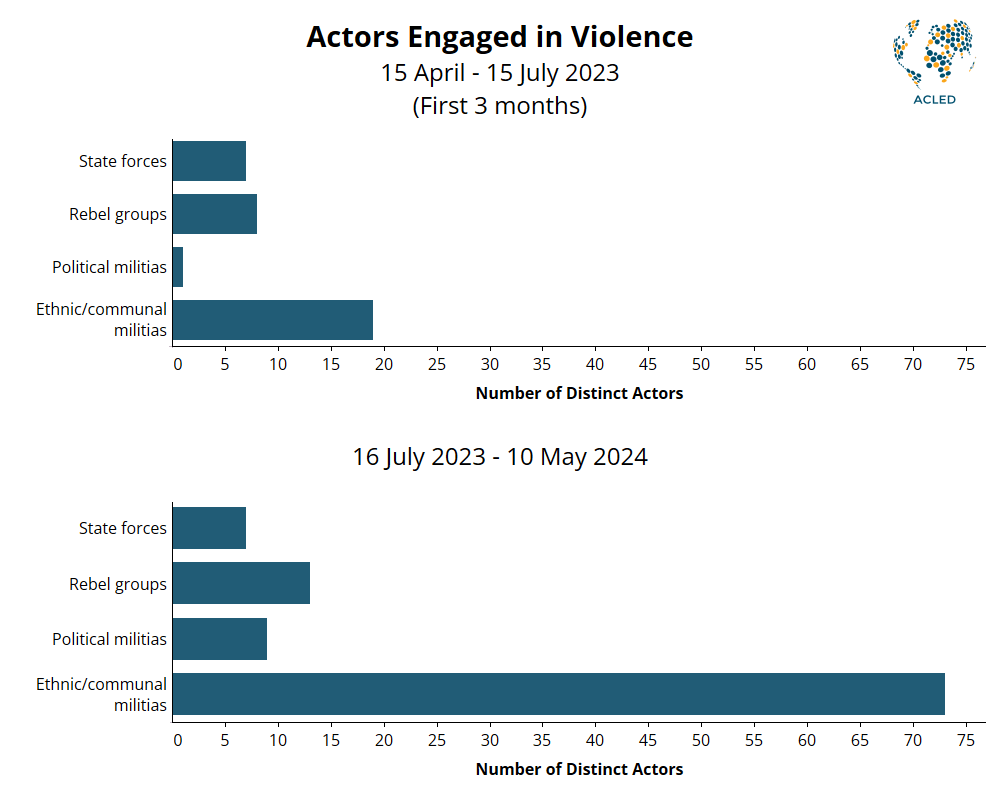

NOHAD: Another problem is how authority has disintegrated during the civil war. In the place of the Sudanese state — and the SAF and RSF — militias have multiplied. Communities are obtaining weapons, armed groups are becoming ethnically based, and alliances are constantly shifting. Although the RSF and SAF are still responsible for by far the biggest share of violent events, they are less in control of the militias’ increasingly independent leaders. Before the war, ACLED was tracking less than 20 of them. Now there are more than 70 of them.

As for the RSF and SAF, they are different, but there is little to choose between them. The RSF increased its reach with more ethnic-based militias and alliances with civilian parties, but these coalitions have often later fragmented. The SAF had some success with its Popular Resistance mass mobilization, but lost credibility with civilian leaders and saw its own militia allies clash.

ALI: This war is very different. There is no unity between the actors. It’s not just between the RSF and SAF. It’s gone way, way down to become a civil war between every ethnic group. The SAF and RSF have become umbrellas for different militias to pursue their own agendas. The people who used to oppress protestors are now fighting alongside the demonstrators’ old resistance committees. Former rivals are allied, former friends are aligned against each other.

How do you track the civil war from far away?

ALI: It’s not easy. Sudan’s war is somehow neglected. You can’t find information on TV or in-depth analysis of the situation.

We look out for news of political violence from carefully vetted and trusted sources. They include professional and neutral news agencies. Since we know that all sources contain bias, we trianguale and cross-check them with others to better understand the details of each event. For instance, if the SAF or RSF report news of clashes, it does usually mean that something happened; we just can’t trust the details since their claims are mostly propaganda. For major events, like armed clashes and the controlling of areas, you can usually find at least three or four reliable sources. People living in areas where violence happens can also provide further information; wegeolocate events from photos and video evidence. All that makes ACLED one of the few places to find data and analysis on the actual conflict.

Not surprisingly, most reporting is about displacement, a category where Sudan is one of the world’s worst cases: The war has forced at least 6.6 million people to leave their homes internally, with perhaps another 4 million taking refuge abroad. Organizations like the United Nations International Organization for Migration are best placed to follow this emergency. Groups like Human Rights Watch follow rights violations in the country. And the UN’s World Food Programme says nearly one-third of Sudan’s population is acutely short of food, with 5 million people facing emergency levels of hunger.

I should say that dealing with the conflict data every day is frustrating. It’s not just the numbers. Every event that we code has a personal story behind it. Every event is a disaster for someone’s relative, someone’s friend, someone’s neighbor, someone who somebody knows. People who lived together for decades are taking up weapons and fighting each other.

There’s also no consistency, the war is difficult to predict. It was a surprise when the SAF suffered a rapid defeat in Darfur, and lost al-Jazirah state south of Khartoum. In some places, it seems like the SAF didn’t have the will to resist. In other places, the SAF really fought back. The RSF is now putting pressure on El Fasher, the SAF’s last strongpoint in Darfur. But the militias there are mobilized against the RSF. Nobody seems able to score a decisive victory.

Outside reporting makes much of all the regional support for one side or the other. What do you make of these?

ALI: Regional interference is affecting the situation, but I’m not sure that the regional powers can guarantee their interests in Sudan through any of the Sudanese actors. The RSF may be ahead one moment, but the next momentum fortune may favor the SAF. The situation in Sudan is not like Syria, with its resilient, long-standing government and its determined international backers. In Sudan, the two actors are much weaker. So outside actors are more cautious.

A man walks while smoke rises above buildings after aerial bombardment, during clashes between the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces and the army in Khartoum North, Sudan, May 1, 2023. REUTERS/Mohamed Nureldin Abdallah

The supply of drones was significant. But the drones are not like the Turkish ones that changed the war for the Ethiopian government. These suicidal drones used in Sudan are not as effective, despite their prolonged reliance during a period of reduced direct armed clashes following the battles in August. Both warring factions engaged in drone warfare against each other, indicating a growing trend toward remote violence. However, this escalation did not significantly alter the control over territories

There have been many reports of new peace talks, maybe led by a new US envoy and hosted in Saudi Arabia. How do you rate their chances of success?

ALI: I don’t think the RSF and SAF will restart serious talks. If they do, it will be like the last one where they couldn’t agree on anything, let alone a ceasefire or humanitarian aid. The RSF didn’t lose too much during this year; the SAF won some small victories, for instance in Omdurman, and it has a lot of allies. There are other forces, too: Loyalists of the old Bashir regime and militias allied with the RSF are against the negotiations.

Basically, as long as there is no clear territorial division, peace talks can’t succeed. The warring parties are gambling, trying to get the upper hand. During previous truces, during the Jeddah talks, they used the time to regroup and mobilize, to attack again once the truce was over.

NOHAD: Peace talks may also be a victim of the ever-stronger militias. Some of these groups were set up after the revolution but before the war and have taken on a dominantly ethnic character. Their groups can be way more violent — they believe that war is the only solution. This dynamic cannot be easily reversed. Even if the RSF and SAF reach an agreement, or if they stop fighting, the grievances and conflicts between these groups during the conflict are what is going to be very hard to settle.

Do you see a way that Sudan can be put back together again?

NOHAD: There’s nobody I know still in Khartoum. I have some relatives in neighboring Omdurman. They are relatively able to function — there are some markets, food can enter from other states. But they have very minimal electricity and telecommunication networks. We can’t communicate with people there. Calls don’t go through. People have to go to specific areas to find a network.

We don’t know what happened to our building or our apartment. All of our neighbors were looted. Everything in Khartoum changed. It’s a ghost town. The buildings are mostly damaged. Houses, cars, banks are all looted. The infrastructure is severely damaged. Most residents left.

To be honest, I can’t see any particular model to inspire a way forward. Nearby countries similar to Sudan haven’t done very well. The best-case scenario would be a secular government that respects human rights and implements a new system of governance in which Sudan’s vast states get their fair share of development and representation. We have to put behind us the monopolization of government by particular tribes, elites, or regions, as has been the case since colonial rule.

The only hope for me is not very logical. It grows from my experience of change on the ground after the fall of Bashir’s regime. The organizations that formed — what we called ‘resistance committees,’ were by definition decentralized. The only thing that links Khartoum and Darfur, say, is that people in both places are pro-democracy, against violence in general. Before the uprising began in 2018, some protests were violent and gave the government an excuse to crack down. But the resistance committees were nonviolent. They really developed, they had their own political charter, [and] they opposed the signature of the agreement on the transitional government that can now be seen as a trigger for the war. These committees are filled with young people. They might be able to come up with a better model than that being pursued by the civilian parties. If there is ever a peace agreement, maybe these grassroots organizations can represent the regions and their needs.

ALI: Unfortunately, I think this war will last a long time. The last two wars between Sudan and what became South Sudan went on for nearly 50 years, until 2005. There is no way Sudan can go back to its pre-war self. And one thing I know for sure is that there is no getting back to Sudan soon for me, either.

Nohad Eltayeb and Ali Mahmoud Ali were in conversation with Hugh Pope, ACLED’s Chief of External Affairs.