Situation Update | May 2024

Kenya: The resurgence of teacher protests and infighting within civilian and security institutions

24 May 2024

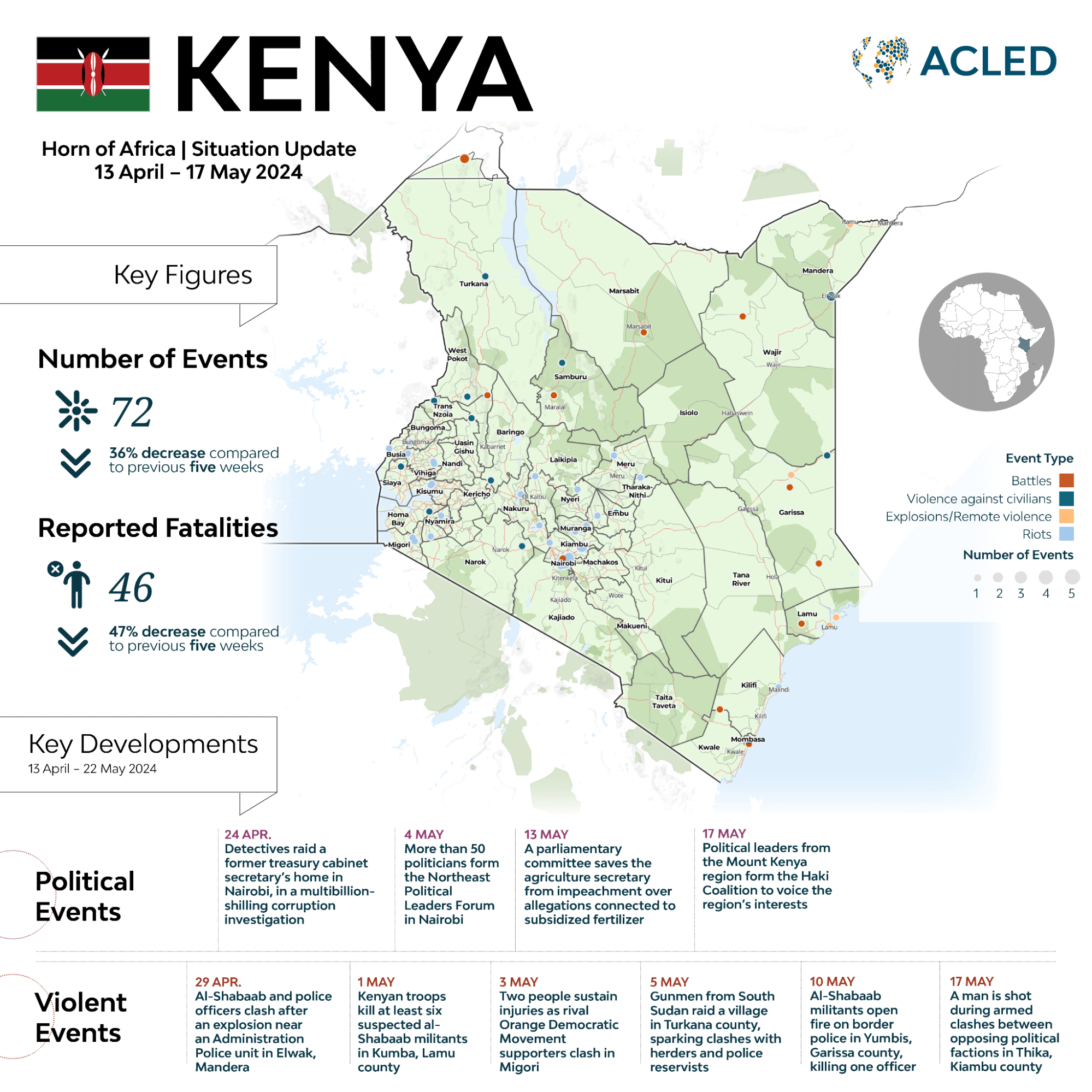

Kenya at a Glance: 13 April to 17 May 2024

VITAL TRENDS

- From 13 April to 17 May 2024, ACLED records 72 political violence events and 46 reported fatalities in Kenya. Most events took place in Nairobi, which saw 12 political violence events. Seven of these 12 violent events were connected with mob violence against suspected thieves.

- Lamu, Nairobi, and Mandera counties had the highest number of reported fatalities, with at least nine reported in Lamu and at least five reported in both Nairobi and Mandera. The fatalities in Lamu and Mandera were linked to al-Shabaab attacks.

- The most common event types during the reporting period were riots, with 38 recorded events, followed by battles, with 16 recorded events. The majority of riots were in Nairobi, with nine recorded events.

The resurgence of teacher protests and infighting within civilian and security institutions

As protests by health workers continue in Kenya, intern teachers initiated their own wave of demonstrations in April and May. This new mobilization highlights other sectoral issues concerning pay, contracts, and worker status. These protests by intern teachers seeking job security and salaries illustrate the broader transition and financial and administrative crisis in Kenya’s education system.1Dr. Audrey Matere, ‘From 8-4-4 to CBC: Emerging Issues of Transition in Education in Kenya,’ International Journal of Curriculum and Instruction, 1 January 2024 Separately, there were sporadic fistfights between elected representatives in Muranga, Nairobi, and Nakuru county assemblies, while military and police clashed in a fistfight in Likoni, Mombasa, and a firefight and siege in Lodwar, Turkana. Such nationwide strikes and intra-governmental violence underscore the difficulties facing President William Ruto as he attempts to address economic grievances and build public confidence in Kenya’s politicians and security forces.2Michelle Gavin, ‘Kenya’s Governance Dilemma,’ Council on Foreign Relations, 22 August 2023

Intern teachers hold demonstrations in southern Kenya

Since mid-April, the number of demonstrations by a group of Junior Secondary School (JSS) intern teachers has increased compared to last year’s demonstrations by the same protestors. The teachers demand that the Teachers’ Service Commission (TSC) pay them full salaries as permanent, pensionable employees in compliance with an order by the Employment and Labor Relations Court of Nairobi, which was issued on 17 April.3Kevin Cheruiyot, ‘Intern teachers demand full salary from TSC after court’s ruling,’ The Nation, 20 April 2024 The court found the TSC violated labor laws by employing student graduates as intern teachers rather than as employees and that the TSC did not have the constitutional power to hire teachers on internship contracts.4Employment and Labor Relations Court of Nairobi, ‘Petition E223 of 2023,’ Kenya Law, 17 April 2024 The ruling came in response to a petition filed on the teachers’ behalf by the Forum on Good Governance and Human Rights on 29 November 2023.

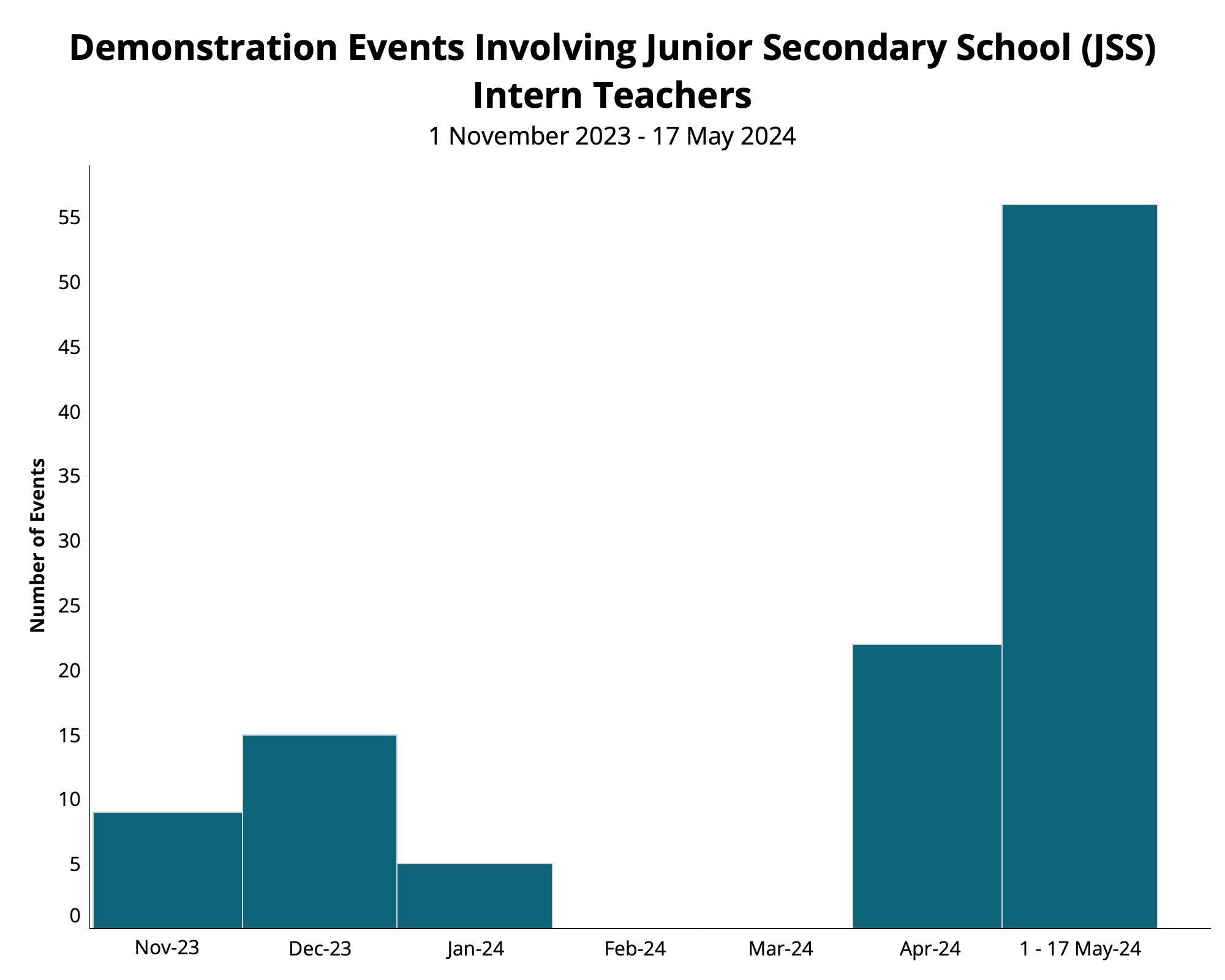

In 2023, there were almost no JSS intern teacher-related demonstrations until around the petition’s filing in November. The demonstrations began on 26 November, three days before the petition was filed. Between 26 November 2023 and 9 January 2024, ACLED records 30 protests by the JSS teachers. The demonstrators are primarily demanding that the government honor their employment agreement in line with the petition. Driven by this uptick in events in late November and December, demonstrations by JSS intern teachers became over half of all teacher-related demonstrations in 2023 — 24 out of 47. Other teacher-related demonstrations often centered on low or delayed pay, insecurity in schools, or relations with government administrators that manage the schools.

However, there were no demonstrations by intern teachers in February or March 2024 while the court was reviewing the case. The court ruling on 17 April spurred a resurgence of activity: From 17 April to 17 May, ACLED records 78 demonstrations by JSS intern teachers across the country. These 78 additional demonstration events have more than doubled the 30 intern teacher demonstrations held between November and January (see graph below).

The JSS demonstrations have been held across southern Kenya since November in cities like Nairobi, Mombasa, and Eldoret, county capitals like Kakamega and Kiambu, and small provincial towns like Mukuyuni (Bungoma County) and Kabarnet (Baringo County). These demonstrations have remained peaceful and widespread across Kenya. They are also often joined by representatives of the Kenya Union of Post Primary Education Teachers (KUPPET), a union that has been active in other teacher-related demonstrations. KUPPET’s secretary-general demanded an immediate end to new TSC internship contracts and joined teachers in calling for the implementation of the ruling for the 46,000 teachers already on contracts.5David Muchunguh, ‘Teachers will oppose CS Kuria jobs plan, says Kuppet,’ The Nation, 2 May 2024

However, the government filed an appeal on 20 April, which put the ruling on hold despite the court labeling the appeal as “urgent.”6Education News, ‘Temporary relief for TSC as ruling on internship is put on hold,’ 20 April 2024 Protests may continue in the short term as JSS teachers hold fast in their demands for enforcement of the ruling and cooperation from the government. On 13 May, the situation escalated from demonstrations around the country to a coordinated strike with accompanying demonstrations by JSS teachers, supported by KUPPET.7Citizen Digital, ‘JSS Teachers Kick Off Nationwide Strike As Court Now Orders Them Back To Class,’ 13 May 2024 This strike has delayed the beginning of second-term classes in Kenya’s JSS, despite the court ordering the teachers back to classes while it considers the appeal.8Citizen Digital, ‘JSS Teachers Kick Off Nationwide Strike As Court Now Orders Them Back To Class,’13 May 2024

Infighting between politicians and security forces

During the reporting period, there have been multiple incidents of violence between Kenyan political parties or violence between Kenyan security forces. These incidents highlight the often heated nature of Kenyan administration and politics.9Kathleen Klaus, ‘Political Violence in Kenya: Land, Elections, and Claim-Making,’ Cambridge University Press, 14 May 2020 Issues of pay, promotion, and employment can become existential, partisan, and ultimately violent. In particular, there were three instances of members of various county assemblies engaging in physical violence against colleagues over issues of power and personnel. On 16 April, members of the Muranga County Assembly threw chairs and tables at each other during house proceedings in Muranga, shoving each other, assaulting a police officer, and destroying files and property over the ouster of two members of the County Assembly Service Board. One member of the assembly was injured, and damages reached up to 3 million shillings (around 22,900 US dollars). Members of the assembly had tabled a motion to remove the two members over nonpayment of salaries and began the fight when the two members presented a court order halting the motion.10Alice Waithera, ‘Murang’a MCAs go on rampage over delayed pay, allowances,’ The Star, 16 April 2024

Further, on 23 April, members of the Nairobi County Assembly engaged in a fistfight during house proceedings in Nairobi over county-level leadership changes, with no reported injuries. The fight began over one member’s removal from his position as chair of the Water Committee.11Timothy Cerullo, ‘Chaos Break Out Inside Nairobi County Assembly as MCAs Clash Over Leadership Changes,’ Kenyans, 23 April 2024 That same day, Muranga police summoned six members of the Muranga County Assembly over the previous week’s fight in their assembly, and other assembly members demonstrated in support outside the police station. Yet another fistfight ensued in the chambers in Nakuru on 2 May over an impeachment motion against a Chief Executive Committee member. Police and other members of the Nakuru County Assembly broke up the fight, and an unknown number of people were taken to the hospital with injuries.

It is unclear why frequent infights — three — between the members of the county assemblies broke out just between 13 April and 17 May, whereas from 1 January 2023 to 12 April 2024, ACLED records only four such incidents. As these three incidents occurred in different assemblies and were unrelated, it is likely the uptick this month was coincidental and demonstrates an unpredictability in Kenyan political clashes.

Similar infights were also reported between Kenya’s security forces. The Kenya Defence Forces and police have historically had poor communication and inter-force rivalry.12Africa Intelligence, ‘Tension between police and army over joint security operation in northern Rift Valley,’ 6 March 2023; Emmily Humprey, ‘The Battle for Authority: Bridging the Divide Between Kenya’s Defenders,’ 15 May 2024; Fred Mukinda, ‘Attack revives old rivalries between police and army,’ Nation, 7 April 2015 These institutional rivalries have hindered national security initiatives and have recently turned violent.13Mwangi Muiruri, ‘KDF versus police: The supremacy wars derailing banditry security operation,’ Nation, 17 April 2023 On 17 April, four Kenyan soldiers assaulted and disarmed a police officer near Turkana University College, near Lodwar town in Turkana county, for allegedly delaying the removal of road spikes. Police arrested the soldiers, but their station was stormed by more than 10 other soldiers. The situation was only defused after negotiations between local military officials and the sub-county police commander. Subsequently, the Kenya Defence Forces denied that their troops had fired into the air or assaulted the officer, and accused police of “creating alarm.”14Benjamin Muriuki, ‘KDF Denies Lodwar Assault Incident, Accuses Police Of Embarassing And Humiliating Soldiers,’ Citizen Digital, 18 April 2024 But video of the incident has gone viral and raised public questions over the conduct and discipline of Kenya’s security institutions.15Valentine Obara, ‘KDF versus Police: Inside the incessant fights between KDF and Police,’ Nation, 29 April 2024

Separately, on 27 April, more than five military officers clashed with police officers and private security guards at a ferry crossing in Likoni in Mombasa county after the soldiers blocked the crossing with their land cruiser. Two days later, military, police, and private security, joined by Kenya Ferry Services and Ports Authority officials, held a reconciliation meeting at the crossing. Similar to the spike in violence involving members of county assemblies, there were three battles between military and police just between 13 April and 17 May, while from 1 January 2023 to 12 April 2024, ACLED records only one such incident.

Violence between political actors and between security actors will likely continue sporadically and unpredictably, though battlegrounds for such clashes have historically emerged around the Kenyan elections.16Gilbert Khadiagala, ‘Kenya’s political elites switch parties with every election – how this fuels violence,’ The Conversation, 16 May 2023 Though instances of factionalism, polarization, and inter-institutional rivalries in Kenya may undermine the government’s image and effectiveness, efforts such as the ferry crossing reconciliation demonstrate that intra-governmental mediation is possible.17Victor Abuso, ‘Kenya is heading in the wrong direction, citizens tell Ruto as he marks one year in office,’ The Africa Report, 14 September 2023