Q&A with

Ladd Serwat and Héni Nsaibia

ACLED Africa Regional Specialist and Associate Analysis Coordinator for West Africa

How has Russian mercenary activity in Africa been affected by the death of Wagner Group leader Yevgeny Prigozhin on 23 August 2023 and the subsequent formation of Africa Corps? In this Q&A, ACLED’s Africa Regional Specialist Ladd Serwat and Associate Analysis Coordinator for West Africa Héni Nsaibia say Russia has taken the opportunity to step up military activity, more closely control mercenary operations, and expand its footprint on the continent.

In the year since the death of Wagner Group leader Yevgeny Prigozhin, what has changed for Russian mercenaries in Africa’s Sahel?

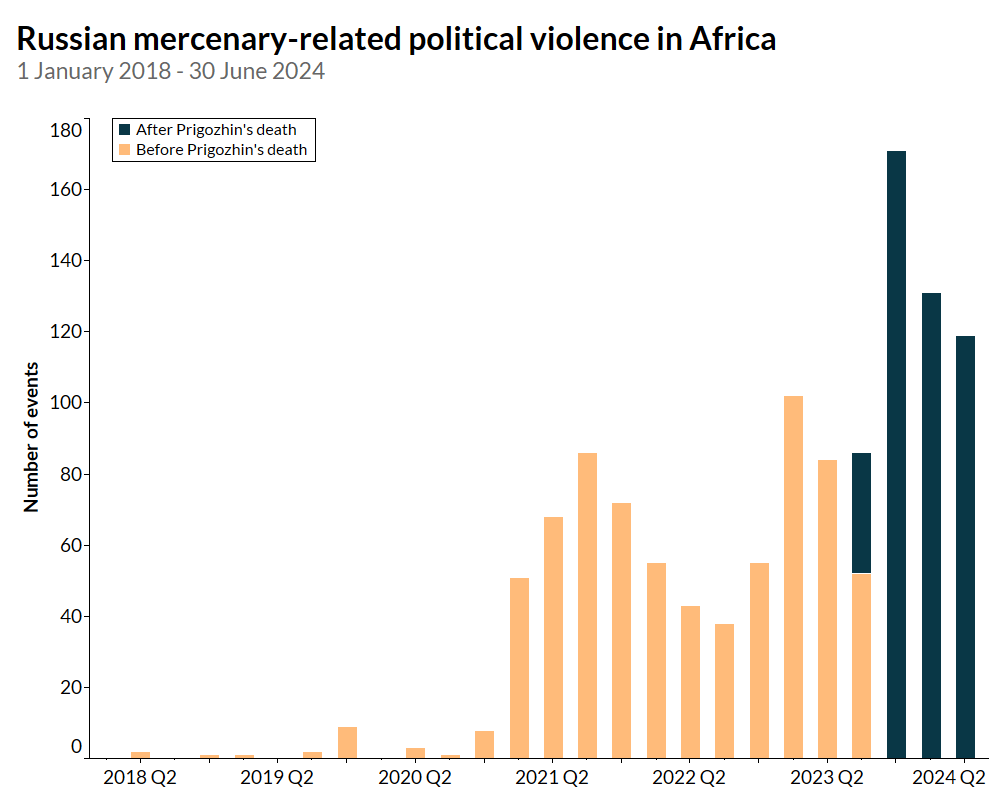

Ladd Serwat: The most important thing to be said is that, even after the death of the Wagner Group’s Yevgeny Prigozhin, violence involving Russian mercenaries has increased in Africa. In the fourth quarter of 2023, ACLED data show that activity doubled from the previous quarter — whether it was under the name of Wagner or any of its successor organizations like ‘Africa Corps.’ The first two quarters of 2024 also saw more Russian mercenary-related political violence events in Africa than when Prigozhin was alive (see graph below).

One year ago, Russian Wagner mercenaries already appeared to have become an indispensable actor in the Sahel, supporting coups, fighting jihadists, defending dictators, and generally taking over from France, the former colonial power. Then came the Wagner Group’s short-lived June 2023 rebellion against the government in Russia, their failed march on Moscow, and, on 23 August 2023, the death of the Wagner Group’s leader Prigozhin and several senior Wagner officials in a suspicious plane crash.

After Prigozhin’s death, many expected Moscow would just shut down the private military company (PMC) and force its mercenaries to either sign contracts with the Russian military or quit. We saw some of this pressure in June 2023 before Prigozhin and Wagner Group staged their revolt and one-day march on Moscow. And while many Wagner mercenaries fighting in Ukraine were pressured to sign with the military, quit, or sign with smaller PMCs, the approach in Africa has been different.

Is that where the name ‘Africa Corps’ comes from? Is the group the same as the Wagner Group?

Ladd Serwat: After some early official Russian reports in late 2023 designated the mercenaries as the Africa Corps, international commentators now often use this name to refer to Russian mercenaries in general.

In Sahelian countries, however, the group is still collectively referred to by its old name, the Wagner Group. In the capital of the Central African Republic, Bagui, you still see people wearing Wagner T-shirts and referring to Russian mercenaries as ‘the Wagner Group.’ So, for now, we tend to refer to the mercenaries as both the Wagner Group and Africa Corps.

There have been changes to key leaders and country-level management; however, that differs from country to country. We have also seen new contracts for fighters under a new paramilitary structure, in addition to dispersing other contracts to much smaller PMCs in the region. Russia seems to want to avoid one organization amassing too much power and posing a threat, as was the case with the Wagner Group under Prigozhin.

There has also been a change in the degree of connection to Moscow. Only in June 2023, two months before Prigozhin’s death, did Russian President Vladimir Putin admit to financing the Wagner Group. Before then, the group had been used to create a degree of separation between Russia and direct military action. There was a certain deniability: Moscow could say the Wagner Group didn’t exist or that there was no direct link. However, the new Africa Corps has become a much more direct extension of the Russian Ministry of Defense (MoD), and Moscow has admitted to financing it.

Africa Corps also looks to be more focused on security and military operations. Under Prigozhin, the Wagner Group was more of a complex web of Prigozhin-linked businesses involved in various activities, such as gold mining, timber, and oil, in addition to private security and military operations.

Héni Nsaibia: Africa Corps is like the new face of the Wagner Group’s involvement in Africa. It serves the Russian state’s strategy in Africa and its effort to rein in, control, and restructure the Wagner Group since Prigozhin’s death.

Still, whatever it is, understanding the Wagner Group’s restructuring or rebranding it to Africa Corps is all based on relatively scarce and recent reports. Africa Corps still doesn’t even have a logo. They supply certain services, advisers, training, maintenance, and operational assistance. They are also no longer really mercenaries. As Ladd says, they are more supervised by the Russian MoD and military intelligence.

In practice, the Wagner Group still exists in spirit. The rank and file perceive themselves as the Wagner Group; it’s a sociological thing. When Russian mercenaries captured Kidal in northern Mali in November 2023, they raised the Wagner flag on the fortress. Similarly, Wagner-linked Telegram channels continue to release material and engage in recruitment campaigns in the PMC’s name. Some rebranding started after that, but all these things are different faces of the same object.

What do these changes actually look like on the ground, for instance, in Mali?

Héni Nsaibia: We’ve seen more continuity and evolution than an abrupt change in Mali, where Russian mercenaries are currently most active. The structure appears to remain the same, supposedly under the leadership of Ivan Maslov, but he now seems to be assisted or overseen by officers from the main Russian military intelligence organization.

When Prigozhin died, Mali was already in the middle of a military offensive to reconquer the north of the country. It was always going to be very deadly, and so it proved. The Malian Armed Forces (FAMa) and the Russians have intensified activity, attacked insurgent groups, and engaged heavily in violence against civilians. They don’t distinguish much between combatants and non-combatants. If they see complicity on the part of some villages, they use very brutal tactics, as we highlighted in our report on the group in 2023. This includes decapitation, summary shootings, and burning of victims, even when still alive. This is an integrated approach by the Wagner Group. FAMa was doing this before, but it has now become systematized.

The recent fighting on the border with Algeria has added to regional polarization. Burkina Faso supports the Malian forces involved in the fighting, which the rebels from the Strategic Framework for the Defense of the People of Azawad (CSP-DPA) have condemned. In addition, the Malian regime now accuses the regional power Algeria of acting in a hostile manner and harboring rebel groups. This new phase in the conflict has further diminished hopes for reconciliation and exacerbated political tensions. Countries such as Algeria and Burkina Faso, which have played a decisive role as mediators in the past, are now being drawn more directly into the conflict.

Why has Mali become so violent?

Héni Nsaibia: Mali’s been in crisis since 2012. The violence took on regional proportions after France’s intervention, the arrival of jihadi groups, and the spread of the insurgency to other Sahel states. The current Malian and Russian offensive includes high levels of civilian targeting against northern Mali groups like Tuareg, Arabic-speaking tribes, and Fulani. FAMa and the Wagner Group have engaged in the pillaging of artisanal gold mines; the seizing of vehicles; and the arrest, interrogation, and summary executions of people who get in the way. There’s no ambiguity about it: The joint offensive involves moving out as many unwanted people as they can.

ACLED has tracked an 81% increase in violence involving Russian mercenaries in Mali since Prigozhin’s death compared to the year prior and a 65% increase in reported fatalities. Since it deployed to Mali in December 2021, we’ve seen the Wagner Group take part in 34% of FAMa operations. Since then, 60% of violent events involving Wagner forces were targeted at civilians. These incidents were primarily captured in the dataset through ACLED’s local sources. Operations peaked in 2023 when more than 1,000 Russian mercenaries were stationed in Mali. The conflict has also rapidly become more technological through the multipurpose use of drones, but especially the growing use of drone-delivered explosives by different actors, in particular Wagner mercenaries and insurgents from the al-Qaeda-affiliated Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin (JNIM).

FAMa and the Wagner Group have also committed mass killings of civilians, torture, abductions, and looting, particularly of cattle. In one instance, they beheaded five people and put their heads on sticks in the center of the village.

Beyond Mali, what else has changed over the past year for Russian mercenaries in Africa?

Ladd Serwat: Since the Wagner Group started operating on the African continent, ACLED has tracked political violence linked to the group in seven countries: Libya, CAR, Chad, Mali, Mozambique, Sudan, and Mauritania. Beyond political violence, the Wagner Group and other Russian PMCs have been involved in other activities, such as disinformation campaigns in the Democratic Republic of Congo and political intervention in Madagascar.

Following Progzihin’s death, Russian PMCs of course continue to engage in political violence in CAR and Mali, but we’ve even seen some recent events across the border in Mauritania. The United States also carried out airstrikes against Russian mercenary bases in Libya in December 2023. Russian PMCs have now been deployed to Burkina Faso and Niger, sending about 100 soldiers to each country. So far, operations in Burkina Faso and Niger remain limited to some training and security services, with no recorded direct political violence.

The deployments to Burkina Faso and Niger show signs that the new Wagner/Africa Corps operations may be pivoting away from CAR and toward the Sahel, but the Wagner Group’s presence in CAR has always been a bit different from the other contexts. Under Prigozhin, the Wagner Group was deeply entrenched in a variety of business ventures, political advising, disinformation campaigns, and even Russian culture programs. Shifting former Wagner personnel and contracts has taken longer in CAR compared to other places, but that may not mean that Africa Corps has lost interest in the country.

Héni Nsaibia: The deployments to Burkina Faso and Niger haven’t had any impact in terms of conflict dynamics that we’ve seen yet, but they definitely have political implications. The presence of Russian troops in Niger and the regime-ending military agreements have caused western forces to withdraw — through negotiation with forces from the US and Germany or by being expelled, in the case of the French.

President Ibrahim Traoré made his first public appearance with Russian militiamen bearing the insignia of BEAR, another Russian PMC, in Burkina Faso on 25 July 2024. They were acting as his guard. BEAR is not exactly the same as the Wagner Group/Africa Corps but operates in the same sort of network, being connected to Russian military intelligence and the MoD. A BEAR PMC representative has formed part of an official Russian delegation, highlighting the extent to which the Wagner Group/Africa Corps, smaller PMCs, and Russian forces are now explicitly linked.

What kind of success is the Wagner Group/Africa Corps winning for its African patrons?

Héni Nsaibia: When it comes to results from this counter-insurgency campaign, it’s a mixed bag.

On the plus side, Malian forces have successfully returned to places they had withdrawn from, like Kidal in the north, and have expanded in the center. At the same time, the Wagner Group has had only a limited impact on JNIM, one of the main jihadist groups. Their military advantages have forced JNIM into a more defensive posture. JNIM now engages in more remote violence, that is, suicide car bombs, landmines, artillery, or IEDs. However, in the far eastern province of Menaka, the Wagner Group has not been able to rival jihadist militants, the Islamic State (IS) Sahel. The Malian and Russian forces are largely confined to the main provincial town of Menaka; you can’t really call that success. Still, when IS Sahel attacked Menaka, the Wagner Group played a key role in the city’s defense. Because of that, I wouldn’t say they are becoming more professional or that they are really successful. There are boom and bust cycles. One side gets momentum for a while, but it can dramatically shift.

In Burkina Faso, jihadist militants are launching full frontal offensives against state forces. However, such offensives are less feasible in Mali due to the presence of Wagner mercenaries, who provide substantial defensive capabilities and military equipment that deter ground assaults.

Some people say the Wagner Group is winning the psychological war by changing the balance of fear. While jihadi groups used to be considered the primary source of fear, people are now more frightened of Russian mercenaries. This is evidenced by defections from JNIM and IS factions in the areas of Douentza and Ansongo, something that is primarily driven by intensified pressure from the Wagner Group’s military operations.

The Wagner Group/Africa Corps’ approach creates a lot of instability, too. They have displaced hundreds of thousands of people, and their brutality impacts the civilian population. So yes, the Wagner Group/Africa Corps has been able to suppress rebel groups and take back territory, but it hasn’t been able to support the government and reach political settlements that bring a real end to the violence. The same rebel groups are still operating, and still a threat to the country, in multiple areas. I would expect that to continue.

Ladd Serwat: In CAR, the Wagner Group and the military — along with allied armed groups — had initial success in suppressing levels of violence carried out by rebels in late 2020 and 2021. It also provided support in taking back numerous areas from various armed groups. However, this has yet to fully resolve the capacity for rebels to regroup and conduct smaller offensives. For example, in the later part of 2022 and early 2023, political violence rose once again following a rebel offensive. Like before, the Wagner Group and other allies were able to defend positions across the country, but numerous armed groups continue to operate in CAR. We are also seeing rising political violence in CAR again in recent months amid a rise in rebel group activity. While it is too early to understand the Wagner Group’s response fully, this exemplifies the limited capacity of the mercenaries to pacify violence in the country.

What differences do you see in the behavior of the Russian mercenaries and the former French military supporters of the Sahelian regimes?

Héni Nsaibia: The actions of the French and Russian forces are like night and day. The French abided by certain rules of engagement, target acquisition, verification, and avoiding civilian casualties as far as possible. This is evidenced by our data. The number of civilians killed in over a decade of French engagement was around 100 civilians at the most. This is comparable to just a single Wagner attack.

Strategically, it’s tricky. The French had far more capabilities, but they prevented the Malian army from capturing Kidal, while the Wagner Group/Africa Corps got them there. The French used to meddle in Mali. They used their assets in their own interest and wouldn’t get involved in ground operations while Malians were dying like flies. The Wagner Group, on the other hand, is close to the local troops on the ground.

The Sahelian regimes view the Wagner Group’s presence as a win-win. In Mali, they pay $10 million a month for protection. That’s more than they spend on the budgets for major ministries like justice, family affairs, or environment.1Jean-Michel Bos, ‘Wagner costs African states a fortune,’ Deutsche Welle, 18 March 2023

Ladd Serwat: I’d agree. From the perspective of these Sahelian regimes, the removal of the French military and pivot toward Russian mercenaries permits a security partnership that is more flexible and willing to regain territorial control at all costs. In areas where the Wagner Group/Africa Corps has been able to gain control from other armed groups, some civilians have benefited from these changes in authority and maintain a positive view of Russia. Armed groups have gained power by forming alliances and receiving training from Russian mercenaries.

As Héni mentioned, violence targeting civilians and alienation of local populations is a concern, especially in rural areas, given the extent of civilian targeting by the Wagner Group/Africa Corps against anyone suspected of working or collaborating with rebels or insurgent groups. In CAR, Russian mercenary operations in 2024 have been especially dangerous to civilian populations, with the reported number of civilians killed by the Wagner Group this year already eclipsing the total for 2023 and reaching levels of quarterly civilian targeting events not seen since early 2022.

What future do you see for the Wagner Group/Africa Corps in Africa?

Ladd Serwat: The Wagner Group/Africa Corps’ influence is definitely rising, as we foresaw in our 2024 Conflict Watchlist report on Sahelian states.

I expect that in the coming six months or year, we will see the Wagner Group/Africa Corps training state forces in Niger and Burkina Faso, with the possibility to start engaging in direct violence. The present 100-troop deployment since February/March 2024 is quite small compared to several thousand in CAR and Mali, but it represents the partnership that has officially begun and can quickly send additional forces if required.

Héni Nsabia: Exactly, and the thing is, in Niger and Burkina Faso, these regimes are threatened, thanks to the extreme deterioration of security in both countries. According to Vision of Humanity, Burkina Faso has the highest overall score on the Global Terrorism Index,2Institute for Economics & Peace. ‘Global Terrorism Index 2024,’ February 2024 and ACLED’s Conflict Index shows that it is the second most conflicted country in West Africa. The Russians will likely move on from advisory roles and get more directly involved in violence and military operations. In the past few weeks, we’ve seen numerous large-scale attacks by jihadist insurgents on government forces in these countries. These attacks demonstrate that both regimes are in trouble and need help, and as we’ve seen in Mali, the Wagner Group is not afraid to get its hands dirty.

In ACLED’s Conflict Watchlist piece from January, we discussed the indications that a military base for Russian troops is being built in Burkina Faso. Both countries are building up their capacity to host these troops.

Prigozhin and many other leaders are gone, but the group’s level of activity has only increased.

Ladd Serwat: We will also be closely watching border events. We have tracked some worrying spillover in the past year or two. There’s not only been the northward push to Mali’s border with Algeria; there were also a few incidents on the Chad border, where the Wagner Group has been equipping armed groups in CAR and sending them across the border into Chad.

We have also seen the Wagner Group expand westward toward Mauritania. I expect to see border areas fall under Wagner/Africa Corps control and their influence spreading into those countries. So, the events we’ve already seen along the CAR/Chad border will likely rise. I would be watching coastal West Africa. As countries in this region face growing violence from jihadist groups, they may be interested in external security partnerships. For example, Benin has already sought support from Rwanda for help against insecurity in the north.

Despite Prigozhin’s death and the Africa Corps rebrand, the Wagner footprint will likely continue to expand across the continent.

Ladd Serwat and Héni Nsaibia were in conversation with Gina Dorso, ACLED’s Communications Coordinator, and Hugh Pope, former Chief of External Affairs.