Watch the recorded webinar examining Rwanda’s security interventions, with a special focus on operations in Mozambique and the DRC.

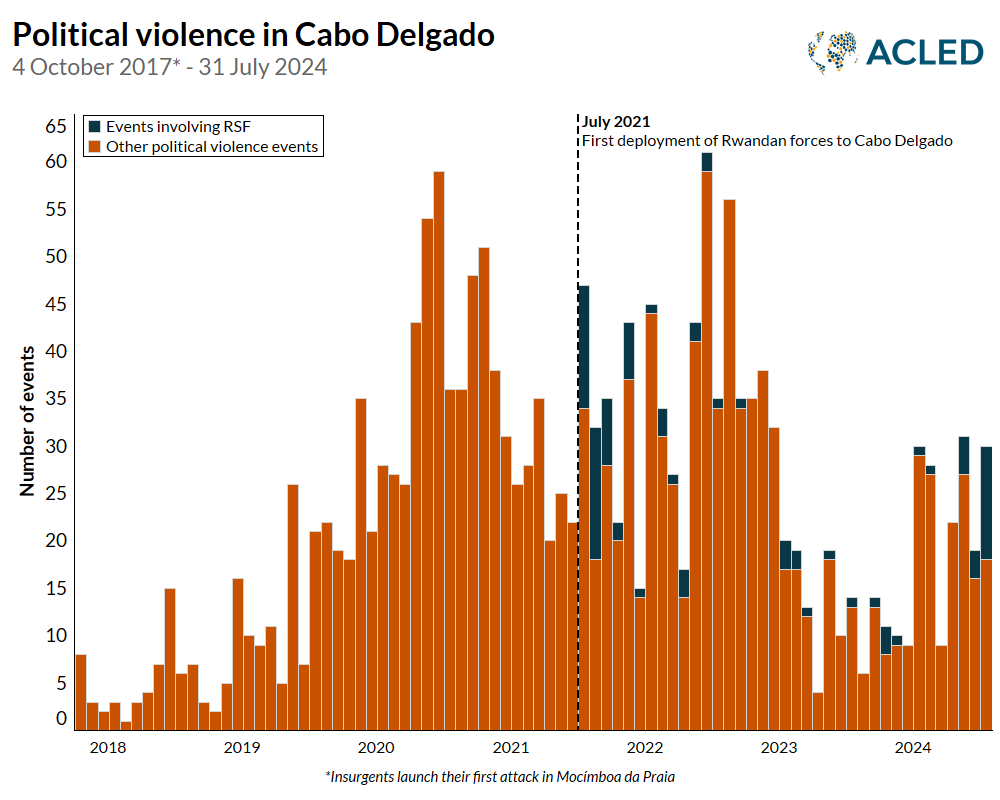

Amidst mounting criticism against the failures of United Nations peacekeeping and Western military involvement, an increasing number of African governments across the continent have demanded the withdrawal of former military partners.1Amongst numerous examples, French direct military operations in Africa ceased in 2022; East African Community (EAC) peacekeepers were withdrawn from the DRC in 2023; and UN peacekeeping operations withdrew from Mali and are in the process of leaving the DRC. These emerging security gaps have been increasingly filled by new armed actors and forms of cooperation, including private military companies, local self-defense groups, and regional partnerships. Having long contributed to multilateral peacekeeping missions, Rwanda has positioned itself as an alternative security partner, sending bilateral missions across the continent.2Federico Donelli, ‘Rwanda’s New Military Diplomacy,’ Institut français des relations internationales, N.31, 2022 The Rwanda Defence Force (RDF) began engaging in further bilateral operations in late 2020 when RDF soldiers and special forces deployed to the Central African Republic to counter a rebel offensive. That engagement expanded in 2021 when Rwanda deployed forces to Mozambique in the face of the rising Islamist insurgency in northern Cabo Delgado province.3Brendon Cannon and Federico Donelli, ‘Rwanda’s Military Deployments in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Neoclassical Realist Account,’ The International Spectator, 24 October 2022

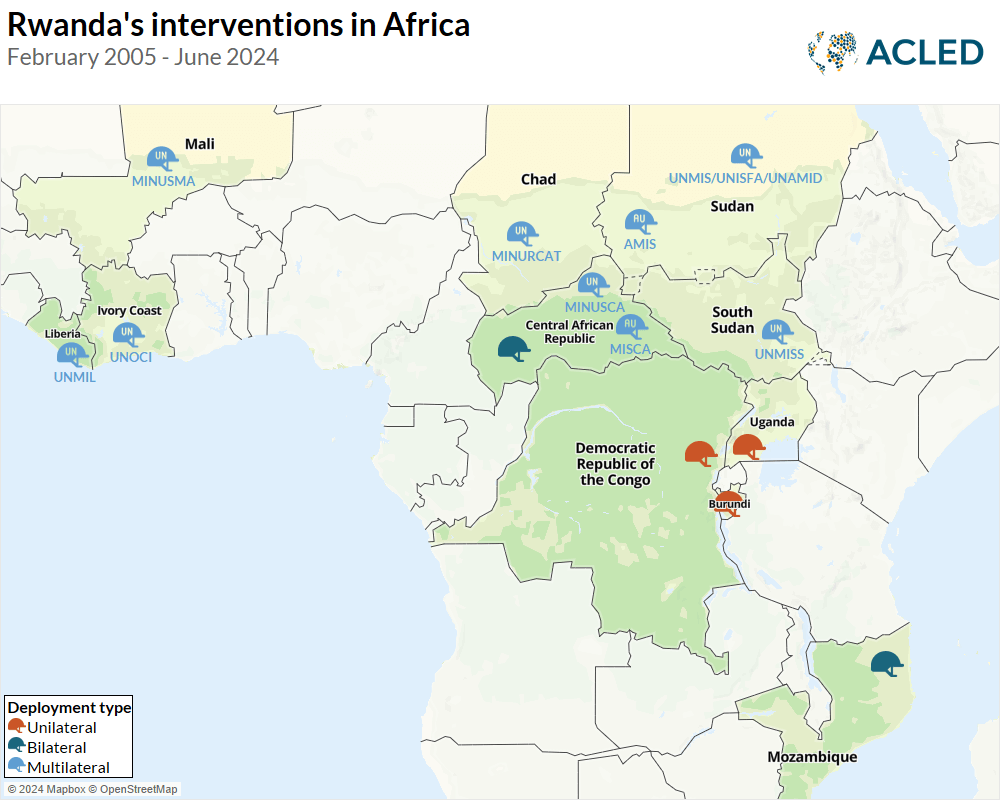

While Rwanda has increased involvement in regional security alongside host governments, since 2022 the bulk of its regional interventionism has shifted toward supporting the March 23 (M23) rebel movement in fighting Congolese military forces (FARDC) and allied militias in the Democratic Republic of Congo (see map below). Although Rwandan troops have carried out low levels of civilian targeting across the continent as a proportion of their total operations in multilateral and bilateral operations, the DRC case shows the increased risks to civilians due to Rwanda’s rising use of artillery shelling and equipping of proxy fighters — a growing concern in the Great Lakes Region.4International Crisis Group, ‘A Dangerous Escalation in the Great Lakes,’ 27 January 2023; UN Security Council, ‘Increased Fighting in Democratic Republic of Congo Exacerbating Security Woes Threatening Regional Conflagration, Special Envoy Warns Security Council,’ SC/15677, 24 April 2024

While several other reports consider Rwanda’s involvement in multilateral operations, this piece examines how Rwanda’s foreign military operations have changed since 2020, drawing on case studies from bilateral operations in Mozambique and unilateral deployment into DRC in support of the M23 rebel group. The case of Mozambique illustrates the RDF’s capacity to support counter-offensives against competing armed groups and suppress levels of violence, but with limited ability to curb civilian targeting from other armed groups, as was the case in CAR. The RDF involvement in Mozambique also illustrates the forms of Rwandan bilateral operations in Africa, including engagement in security, economic activity, and politics. Like its bilateral and multilateral deployments, the RDF’s presence in the DRC provides Kigali with economic benefits obtained by controlling strategic roadways and mining sites.

The growth of Rwandan foreign security engagement

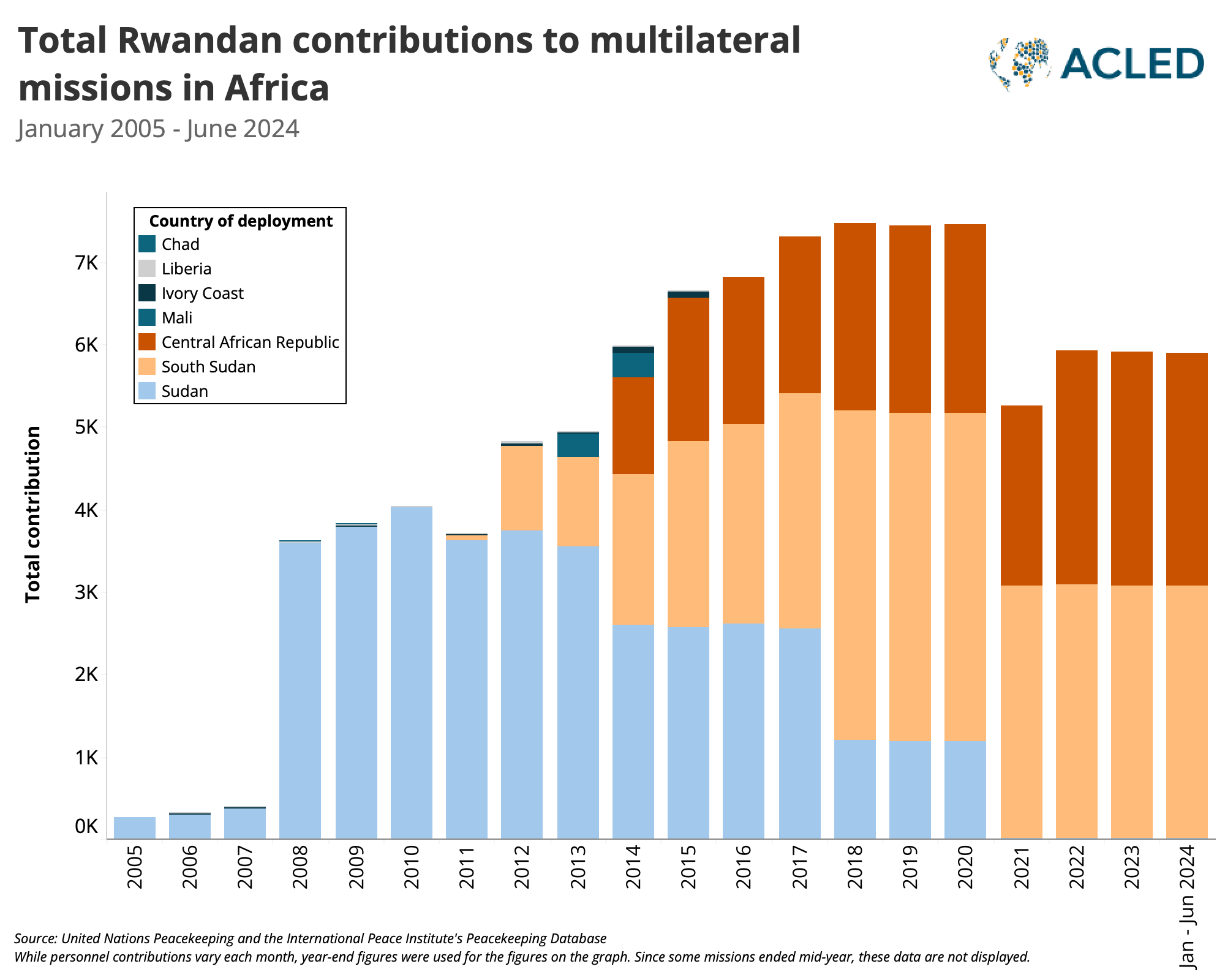

After Rwanda deployed forces into neighboring Zaire — now the DRC — during the Congo Wars from 1996 to a blurry conclusion in 2002, Rwanda turned toward contributing troops and additional personnel for multilateral deployment. Since 2004, Rwanda has increased its deployment to multilateral peacekeeping missions,5UN Peacekeeping, ‘Peacekeeping operations,’ 31 March 2024; Marco Jowell, ‘Contributor Profile: Rwanda,’ School of Oriental and African Studies and Africa Research Group, 22 April 2018 with growing numbers of troops deployed to UN and African Union missions. Rwanda’s foreign security deployments also grew to include bilateral missions in 2020, building international legitimacy as a cooperative partner for multinational security operations. The deployment and deeper integration into peacekeeping and bilateral missions spanning the continent provide political leverage for Kigali, economic resources, and strategic training for Rwandan personnel.6Nina Wilén, ‘From “Peacekept” to Peacekeeper: Seeking International Status by Narrating New Identities,’ Journal of Global Security Studies, March 2022; Marco Jowell, ‘Contributor Profile: Rwanda,’ School of Oriental and African Studies and Africa Research Group, 22 April 2018 Further, Rwanda funds a substantial portion of the national defense budget through contributions from UN peacekeeping missions. Bilateral missions in CAR and Mozambique also provide considerable commercial opportunities for Rwandan firms, some of which are reported to have links to President Paul Kagame’s ruling Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF).7Nina Wilén, ‘A Hybrid Peace through Locally Owned and Externally Financed ssr–ddr in Rwanda?,’ Third World Quarterly, 5 July 2012 For the past 30 years, several large firms owned fully or partly by the ruling RPF developed under party management and expanded into many sectors of the economy.8Nilgün Gökgür, ‘Rwanda’s ruling party-owned enterprises: Do they enhance or impede development?,’ Universiteit Antwerpen, Institute of Development Policy Discussion Papers, March 2012

The growth of unilateral operations and indirect support for the M23 has generated tensions between Rwanda and several Western countries — often the same countries supportive of and reliant upon Rwandan peacekeeping contributions.

Alongside bilateral and multilateral operations, Rwanda deployed troops to the DRC and has increased its military engagement amid the latest M23 offensive. The growth of unilateral operations and indirect support for the M23 has generated tensions between Rwanda and several Western countries — often the same countries supportive of and reliant upon Rwandan peacekeeping contributions. The Rwandan government now balances the criticism and threats for its involvement in the DRC with its contributions to peacekeeping operations, with mixed reception of its bilateral operations. In several instances, Kigali used its position as a significant troop contributor to counter foreign criticism, threatening to withdraw peacekeepers from multilateral missions.9Federico Donelli, ‘Rwanda’s New Military Diplomacy,’ IFRI, N.31, 2022

Spokespersons for Kigali have yet to admit direct military involvement or support for the M23. Instead, Kagame and other Rwandan political leaders increasingly deflect critics’ questions by responding with rhetorical questions that allude to reasons Rwanda’s involvement in the DRC would be warranted. They cite threats to domestic and regional security, including continued operations of the Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda (FDLR) and their collaboration with FARDC, military buildup in Congo, Congolese political rhetoric to invade Rwanda, and violence against Congolese Tutsi.10See, for example, Rwanda Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation, ‘Rwanda Clarifies Security Posture,’ 18 February 2024; Michela Wrong, ‘Kagame’s Revenge: Why Rwanda’s Leader Is Sowing Chaos in Congo,’ Foreign Affairs, 13 April 2023; Charles Onyango-Obbo, ‘Kagame: DRC has crossed red line, war won’t be in Rwanda,’ The East African, 26 February 2023; Musinguzi Blanshe, ‘Rwanda & DRC accuse each other of using rebel groups to their advantage,’ The Africa Report, 10 June 2022; RwandaTV, ‘President Kagame discusses Tshisekedi’s threats, M23 & the DRC, Burundi & FDLR alliance,’ 25 March 2024 Kagame and other Rwandan officials have also noted the colonial construction of the country’s borders, remarking that this part of eastern DRC was formerly part of Rwanda.11RFI, ‘La RDC réagit aux déclarations du président rwandais Paul Kagame sur les frontières congolaises,’ 17 April 2023

For those more critical of Rwanda’s actions, the threats of the FDLR claimed by Kigali are simply a false pretext for Rwanda to continue exerting its economic and political influence in eastern DRC.12Wendy Bashi, ‘‘‘Les FDLR ont toujours été un faux vrai prétexte pour le Rwanda pour continuer à considérer l’Est du Congo comme sa zone d’influence” (Bob Kabamba),’ Deutsche Welle, 14 February 2022 While various studies have long signaled the smuggling of resources from the DRC into Rwanda and other regional neighbors,13UNSC, ‘Midterm report of the Group of Experts on the Democratic Republic of the Congo,’ S/2019/974, 20 December 2019, Section III; IPIS, ASSODIP, and DIIS, ‘Le M23: Enjeux, motivations, perceptions et impacts locaux,’ April 2024 Congolese officials increasingly point to these resource interests and Kigali’s desire to annex part of eastern DRC as motivation for Rwanda’s renewed involvement.14Tom Wilson and Andres Schipani, ‘DRC says Rwandan mineral smuggling costs it almost $1bn a year,’ Financial Times, 21 March 2023; IPIS, ASSODIP, and DIIS, ‘Le M23: Enjeux, motivations, perceptions et impacts locaux,’ April 2024, pp. 5 The replacement of local government officials with M23 militants and supporters throughout areas of North Kivu also provides evidence of Rwandan and M23 interests in local political power.15IPIS, ASSODIP, and DIIS, ‘Le M23: Enjeux, motivations, perceptions et impacts locaux,’ April 2024

Still, increasing sources of drone footage and eyewitness photography of Rwandan soldiers and heavy military equipment in the DRC make denying Rwandan military presence more difficult.16UNSC, ‘Midterm report of the Group of Experts on the Democratic Republic of the Congo,’ S/2023/990, 30 December 2023; Cécile Andrzejewski, ‘Soldiers fallen in silence: Kagame’s unacknowledged war in the Democratic Republic of the Congo,’ Forbidden Stories, 28 May 2024 According to recent estimates, Rwanda deployed around 3,000 soldiers to the DRC — primarily operating alongside the M23 — with further provision of training and equipment for rebel fighters.17Simon Marks and Neil Munshi, ‘Rwandan Meddling Is Deepening Congo’s Deadly Conflict,’ Bloomberg, 19 April 2024; UNSC, ‘Midterm report of the Group of Experts on the Democratic Republic of the Congo,’ S/2023/990, 30 December 2023

Rwanda’s military operations abroad

Multilateral operations

In the aftermath of Rwanda’s involvement in the Congo Wars, Kigali began a process of increasing involvement in multilateral engagements. From 2004 onward, Rwanda’s contribution to peacekeeping efforts permitted Kigali financial and material benefits for their relatively large and experienced military — a considerable workforce to employ following over a decade of conflict, along with a shifting international perception of Rwanda as a stable country with capacity for international investments.18Nina Wilén, ‘From “Peacekept” to Peacekeeper: Seeking International Status by Narrating New Identities,’ Journal of Global Security Studies, March 2022; Laura Mann and Marie Berry, ‘Understanding the Political Motivations That Shape Rwanda’s Emergent Developmental State,’ New Political Economy, 20 May 2015 Rwandan military and political spokespeople tend to point back to the failures of international peacekeeping efforts in Rwanda to underline the need for African troop contributions to multilateral missions.19Federico Donelli, ‘Rwanda’s New Military Diplomacy,’ IFRI, N.31, 2022; International Crisis Group, ‘Rwanda’s Growing Role in the Central African Republic,’ 7 July 2023; Finbarr O’Reilly, ‘Rwanda troops airlifted to start AU mission in Darfur,’ Sudan Tribune, 15 August 2004 Kigali has since grown to become one of the world’s largest contributors of peacekeeping personnel.20Marco Jowell, ‘Contributor Profile: Rwanda,’ School of Oriental and African Studies and Africa Research Group, 22 April 2018 Beginning with a peacekeeping deployment of just 150 soldiers with the AU Mission in Sudan (AMIS) in 2004, by March 2024, Rwanda ranked as the fourth-largest contributor of UN peacekeeping personnel globally and the largest in Africa, with 5,894 personnel.21UN Peacekeeping, ‘Peacekeeping operations,’ 31 March 2024; Federico Donelli, ‘Rwanda’s New Military Diplomacy,’ IFRI, N.31, 2022 Rwanda’s contributions to peacekeeping missions have spanned several countries in Africa (see graph below).22Marco Jowell, ‘Contributor Profile: Rwanda,’ School of Oriental and African Studies and Africa Research Group, 22 April 2018 The type of personnel for these multilateral missions varies and includes police, soldiers, and advisers.

In CAR, Rwanda has grown to be the largest troop contributor for the UN Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in the Central African Republic (MINUSCA), making up nearly 20% of peacekeeping forces as of 31 March 2024. Rwanda provides MINUSCA with around 2,100 soldiers, 700 police, and 30 additional staff officers, led by Rwandan commissioner Christophe Kabango Bizimungu.23Christophe Châtelot, ‘The Central African Republic, Rwanda’s land of opportunity,’ Le Monde, 3 July 2024; International Crisis Group, ‘Rwanda’s Growing Role in the Central African Republic,’ 7 July 2023 While reporting does not allow for differentiation between Rwandan or non-Rwandan peacekeepers, violent engagement through multilateral missions in CAR has been focused on battling armed groups, making up 80% of violent peacekeeping events involving MINUSCA since 2013.

Bilateral deployments

Although Rwanda continues to increase its peacekeeping contributions, numerous countries in Africa are drawing down or expelling multilateral operations and looking for alternative security partners.24Richard Gowen and Daniel Forti, ‘What Future for UN Peacekeeping in Africa after Mali Shutters Its Mission?,’ International Crisis Group, 10 July 2023 Bilateral military agreements often move faster and offer more flexibility than multilateral peacekeeping missions with numerous stakeholders.25Jessica Moody, ‘How Rwanda Became Africa’s Policeman,’ Foreign Policy, 21 November 2022 Several actors, including private military companies and foreign militaries, have been willing to fill the security gap left by multilateral peacekeeping missions in Africa. Aside from occasional joint endeavors with military forces in the DRC, Rwandan bilateral military operations began in earnest with the deployment of hundreds of soldiers to CAR to counter a rebel offensive in late 2020.26Jeune Afrique, ‘Présidentielle en Centrafrique : le Rwanda et la Russie envoient des troupes,’ 21 December 2020 Rwanda further expanded bilateral deployments in July 2021 by sending 1,000 soldiers to Mozambique during escalating violence involving Islamist insurgents in the northern Cabo Delgado province.27Reuters, ‘Rwanda deploys troops to Mozambique to help fight insurgency,’ 9 July 2021; Ivan Mugisha, ‘Rwanda deploys troops to CAR under bilateral arrangement,’ The East African, 22 December 2020

Bilateral missions provide Kigali and host governments with more flexible mandates for military engagement than AU or UN peacekeeping missions, allowing for a wider range of operations and partnerships.

Rwanda’s bilateral military policy combines political, security, and economic engagement to further the country’s foreign policy.28Federico Donelli, ‘Rwanda’s New Military Diplomacy,’ IFRI, N.31, 2022; Brendon Cannon and Federico Donelli, ‘Rwanda’s Military Deployments in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Neoclassical Realist Account,’ The International Spectator, 24 October 2022; International Crisis Group, ‘Rwanda’s Growing Role in the Central African Republic,’ 7 July 2023 Following Rwanda’s bilateral deployment to CAR and Mozambique, numerous Rwandan businesses were started in the host countries with tax-break incentives and agreements over land and mineral rights, diversifying Rwanda’s domestic dependence on agriculture.29Brendon Cannon and Federico Donelli, ‘Rwanda’s Military Deployments in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Neoclassical Realist Account,’ The International Spectator, 24 October 2022 Missions abroad also generate foreign revenue as host governments pay for troop deployment in foreign currency or in exchange for natural resource rights.30Flore Monteau, ‘Rwandan entrepreneurs seek El Dorado in Central African Republic,’ The Africa Report, 3 January 2024; Marco Jowell, ‘Contributor Profile: Rwanda,’ School of Oriental and African Studies and Africa Research Group, 22 April 2018 Since 2020, Rwanda has expanded its number of embassies, increased the number of diplomatic visits undertaken by its top officials, and formed socioeconomic cooperatives for Rwandans living abroad.31International Crisis Group, ‘Rwanda’s Growing Role in the Central African Republic,’ 7 July 2023 In areas of security, Kigali has long maintained an interest in securing threats from neighboring countries and uses an extensive foreign intelligence network.32Michela Wrong, ‘Do Not Disturb: The Story of a Political Murder and an African Regime Gone Bad,’ Public Affairs, 30 March 2021; Marco Jowell, ‘Contributor Profile: Rwanda,’ School of Oriental and African Studies and Africa Research Group, 22 April 2018; Human Rights Watch, ‘“Join Us or Die”; Rwanda’s Extraterritorial Repression,’ 10 October 2023

Bilateral missions provide Kigali and host governments with more flexible mandates for military engagement than AU or UN peacekeeping missions, allowing for a wider range of operations and partnerships. Peacekeeping mandates tend to restrict operations to a more defensive security posture and are focused on protecting civilians.33Brendon Cannon and Federico Donelli, ‘Rwanda’s Military Deployments in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Neoclassical Realist Account,’ The International Spectator, 24 October 2022 The bilateral mandates have also resulted in various security partnerships with the RDF and allied actors. In CAR and Mozambique, the RDF has operated alongside the host country’s military forces but overlapped with multilateral forces. Rwandan troops joined operations alongside UN peacekeepers in CAR and Southern African Development Community (SADC) troops in Mozambique.34Reuters, ‘Rwanda deploys troops to Mozambique to help fight insurgency,’ 9 July 2021 In CAR, Rwandan special forces also fought alongside Wagner Group mercenaries during counter-offensives against rebel groups. During the initial counter-offensive in CAR from December 2020 through May 2021, Wagner Group mercenaries and military forces — allies of the RDF — attacked civilians more frequently than they clashed against rebel groups. Eventually, Rwandan special forces ended joint operations with Wagner Group, citing human rights concerns and violence targeting civilians.35Jessica Moody, ‘How Rwanda Became Africa’s Policeman,’ Foreign Policy, 21 November 2022

Unilateral interventions

Alongside cooperation with partner governments during multilateral and bilateral missions, Rwanda has also engaged in several unilateral operations since the Congo Wars. According to ACLED data, with coverage that dates back to 1997, 92% of violent events carried out by the RDF during unilateral deployments have taken place in the DRC. These military excursions into Rwanda’s western neighbor began with deep involvement in the Congo Wars as it pursued former Rwandan political leaders and fighters from the previous regime.36Jason Stearns, ‘The War That Doesn’t Say Its Name: The Unending Conflict in the Congo,’ Princeton University Press, 1 February 2022 Violent incidents involving Rwandan military forces during unilateral deployments decreased in the early 2000s, yet Kigali maintained involvement in the DRC through support for armed groups and occasional direct military operations.37Human Rights Watch, ‘DR Congo: M23 Rebels Committing War Crimes,’ 11 September 2012

Aside from the DRC, Rwanda has also had occasional skirmishes on the borders with Burundi and Uganda. Between 2019 and 2022, several cases of violence broke out when the RDF fought with military forces in Uganda near their shared border during a tense period as the two countries traded accusations of supporting political dissidents and undermining security.38Filip Reytjens, ‘Rwanda has reopened the border with Uganda but distrust could close it again,’ The Conversation, 10 March 2022 Similarly, in June 2022, the RDF carried out a multi-day offensive into Burundi against armed groups in the border Kibira Forest region. This frontier violence between military forces, proxy warfare, and inflammatory rhetoric has often soured relationships between Rwanda and other countries in the Great Lakes region. The strained relations led to several border closures, constrained civilian mobility, and limited commerce with Rwanda’s neighbors.39Africa News, ‘Uganda, Rwanda border reopens after three-year closure,’ 31 January 2022; Cristina Krippahl and Isaac Kaledzi, ‘Burundi-Rwanda tensions rise amid border reclosure,’ Deutsche Welle, 17 January 2024

Bilateral deployment to Mozambique (2021-)

At the invitation of the host government, Rwanda deployed RDF troops and a smaller police contingent to the Cabo Delgado province of northern Mozambique in July 2021. The deployment followed a July 2021 attack by the insurgent group now known as Islamic State Mozambique (ISM) on Palma town in March 2021.40Rwandan Ministry of Defence, ‘Rwanda Deploys Joint Force To Mozambique,’ 10 July 2021 The attack was the culmination of a series of ISM actions targeting towns in the province over the previous 12 months, indicative of the state’s loss of control in the province, which led to the suspension of a nearby liquefied natural gas (LNG) project led by French oil giant TotalEnergies.41Total Energies, ‘Total declares Force Majeure on Mozambique LNG project,’ 26 April 2021 The RDF engaged immediately with the insurgents, with nearly 27 reported battle events between the RDF and ISM in the first two months of deployment.

The deployment to Mozambique, built on several years of enhanced bilateral relations between the two countries, followed a similar strategy to the deployment to CAR. The well-developed diplomatic relationships in both countries enabled rapid bilateral deployment when the interests of both the host country and Rwanda aligned. In the case of Mozambique, relations between President Paul Kagame of Rwanda and President Filipe Nyusi of Mozambique and their respective administrations developed positively over the previous eight years, starting with President Kagame’s visit to Mozambique in 2016, which led to cooperation agreements in various sectors and a commitment to establish a Joint Permanent Commission (JPC) between the two countries. The JPC, which acts as a mechanism for formal exchanges at technical and political levels in areas of common interest, was established two years later.42The Rwanda Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation, ‘The first Joint Permanent Commission of Cooperation (JPBC) between Rwanda and Mozambique was held in Kigali from 18-19 July 2018,’ 19 July 2018

With bilateral relations strengthened, Rwanda was well-placed to deploy when the need arose in July 2021. The positive relationship between the two presidents facilitated navigation through a complex set of interests around the Cabo Delgado conflict. These included the interests of the SADC, which had been publicly pushing for military intervention since May 2020 due to regional security concerns, and of France, with its interest in the LNG project led by TotalEnergies.43SADC, ‘Communique of the Extraordinary Organ Troika Plus the Republic of Mozambique Summit of Heads of State and Government,’ 19 May 2020 In the wake of the suspension of the LNG project, President Nyusi sought Rwandan intervention. In April 2021, just days after the project was suspended, President Nyusi visited Kigali to discuss possible intervention. The following month, at the Summit on Financing African Economies in Paris, he met with President Emmanuel Macron, who spoke of his interest in supporting Mozambique in the fight against “terrorism.”44‘António Tiua, ‘Apoio da França no combate ao terrorismo deve ser formalizado em acordo,’ O País, 19 May 2021 By the end of May 2021, a Rwandan reconnaissance team was in Cabo Delgado, while the first 1,000 soldiers had been deployed in Cabo Delgado province by July of the same year.45Rwandan Ministry of Defence, ‘Rwanda deploys joint force to Mozambique,’ 10 July 2021

Impact of deployment

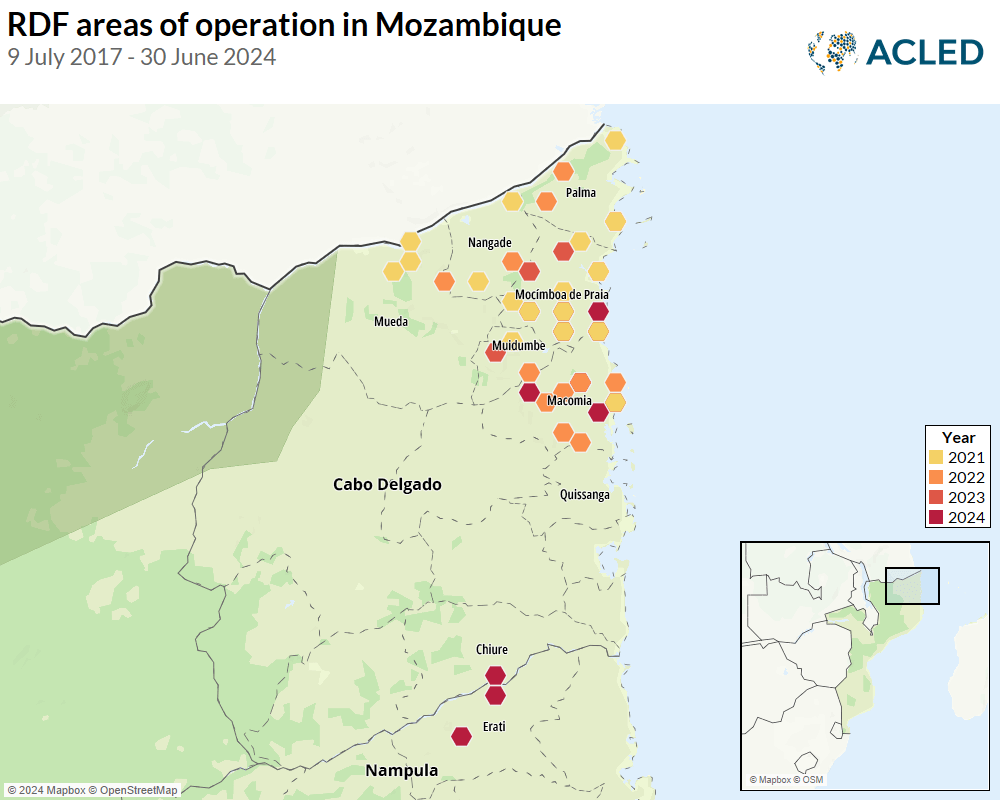

The RDF initially deployed to Palma, first around the LNG plant on the Afungi peninsula near Palma town. Operations in 2021 were concentrated in the Mocímboa da Praia district, reflecting the fight for the recapture of the port and the move against insurgent bases south of the town. Less intense operations across a further five districts that year reflected the pursuit of ISM fighters. In 2022, operations declined by over two-thirds. Though spread across six districts, over 80% of recorded events involving the RDF were in Macomia district, reflecting ISM’s move to the hard-to-access Catupa forest in response to RDF operations — as well as those by the multilateral SADC Mission in Mozambique (SAMIM) — and the economically strategic districts of Mocímboa da Praia and Macomia. Notably, its only permanent presence outside Mocímboa da Praia and Palma districts from 2021 to 2023 was a small base in the Ancuabe district, just 10 kilometers from the main highway linking Pemba, the provincial capital, with the north of the province, as well as with gemstone and graphite mines to its west.46Tom Gould, ‘Rwanda’s Mozambique deployment expands to southern Cabo Delgado,’ Zitamar News, 13 January 2023 Operations in 2023 were almost entirely concentrated in the Mocímboa da Praia district but with notable clashes in Nampula province, the first time the RDF operated outside Cabo Delgado province (see map below).

The RDF’s approach in Mozambique has focused on securing strategic economic projects and operational independence. RDF infantry operations in Mozambique are notable for their emphasis on protecting civilians. Only two incidents of violence targeting civilians have been recorded since 2021. Rwandan military doctrine privileges civilian protection in peacekeeping operations. Rwanda’s central role in the adoption and promotion of the Kigali Principles on the Protection of Civilians helps explain this.47Global Center for the Responsibility to Protect, ‘The Kigali Principles on the Protection of Civilians,’ 29 May 2015 The principles encourage a counterinsurgency posture that seeks community engagement in patrolling practices and restraint in combat in peacekeeping operations.48Ralph Shield, ‘Rwanda’s War in Mozambique: Road-Testing a Kigali Principles approach to counterinsurgency?,’ Small Wars & Insurgencies, 6 October 2023

However, the withdrawal of SAMIM forces in 2024, along with the subsequent increasing reliance on air support, is likely to result in a more aggressive approach to ISM, potentially compromising Rwanda’s commitment to civilian safety. This defensive posture began to shift in 2024, not long after SAMIM troops were withdrawn. In May 2024, RDF troop numbers increased from approximately 2,500 to around 4,000. Up to that point, operations had been conducted with minimal collaboration with SAMIM, which deployed soon after the arrival of the RDF.49Carta de Moçambique, ‘Missão da SADC em Cabo Delgado inicia com 738 soldados e 19 peritos,’ 10 August 2021 Over 2021, 2022, and 2023, ACLED records just seven joint RDF-SAMIM operations, a figure that reflects an unpublished assessment by the government of Mozambique.

As deployment has expanded, incidents involving the RDF have increased significantly. ACLED data show that RDF operations had more than doubled by mid-August compared to all of 2023 (see chart above). This has been accompanied by a change in tactics. In the first half of 2024, combat helicopters were deployed and first used in July and August of that year in operations against ISM positions along the Macomia coast and inland in the Catupa forest. In 2024, the first Rwandan operations took place in the south of the province, in the Chiúre district and the Eráti district of neighboring Nampula province. Thus far, the change in tactics and wider geographic scope of operations has not resulted in any increase in civilian targeting.

The political economy of deployment

Rwanda’s overseas deployments are costly. In 2023, the mission in Mozambique was estimated to cost up to $250 million per year when it numbered approximately 2,000 troops.50International Crisis Group, ‘Rwanda’s Growing Role in the Central African Republic,’ 7 July 2023 There are now almost 4,000 in the country. President Kagame has stated that the operation is largely self-funded.51Luis Nhachote, ‘Kagame: Rwanda is paying for the Cabo Delgado intervention,’ Mail and Guardian, 14 September 2021 Rwanda received additional financial support for the operation from the Council of the European Union, which approved 20 million euros in December 2022.52Council of the European Union, ‘European Peace Facility: Council adopts assistance measures in support of the armed forces of five countries,’ 1 December 2022 Renewal of this support in 2024 has met resistance in some European capitals and has consequently been delayed.53Africa Intelligence, ‘EU split over further funding for Rwandan troops in Cabo Delgado,’ 16 April 2024. Supporting commercial engagement by Rwandan firms can indirectly ameliorate such costs. Overseas operations in Mozambique also allow for Rwanda’s own political and security interests to be addressed.

One Rwandan firm has won a contract to provide security at the LNG project site in Palma district. Securing the site and wider district was a significant, and likely primary, objective of the RDF. In 2021, almost 10% of Rwandan violent engagement was in Palma district, rising to over 20% in 2022. None has been recorded since. The security company is controlled by Crystal Ventures, a Rwandan Patriotic Front-associated holding company.54Fernando Lima, ‘Inside the security firm protecting TotalEnergies’ gas project,’ Zitamar News, 25 July 2024; Zitamar News, ‘Rwandan company wins $800k Mozambique LNG resettlement deal,’ 16 December 2022

Another Rwandan-led firm has been established to explore for graphite, which was found around Ancuabe, where the RDF has a small base. This firm is also reportedly associated with Crystal Ventures.55Africa Intelligence, ‘After security and gas, Rwanda sees graphite opportunities in Cabo Delgado,’ 21 September 2022 Though RDF actions have not been recorded in Ancuabe district itself, Ancuabe is the operating base for operations in Chiúre and Eráti districts. Over 14% of Rwandan actions in 2024 have been in those two districts. There are also more domestic benefits. In January 2022, TotalEnergies agreed to open a permanent office in Rwanda and collaborate in the renewable energy sector there.56TotalEnergies, ‘Rwanda: TotalEnergies signs a MoU with Rwanda Development Board (RDB) to deploy its multi-energy offer and contribute to the development of the energy sector,’ 31 January 2022

Kigali also pursues several political interests in Mozambique. In 2024, Mozambique approved an extradition agreement with Rwanda, a development that the Mozambique Law Society says is linked to Rwandan concern over the presence of Rwandan opposition figures in the country.57Paul Fauvet, ‘Bar association opposed to agreement with Rwanda,’ Agência de Informação de Moçambique, 28 March 2024 Counterinsurgency in Mozambique is directly relevant to Rwanda’s security. Since its inception, the insurgency in Mozambique has been connected to violent jihadist networks across East Africa.58Saide Habibe, Salvador Forquilha, and João Pereira, ‘Islamic Radicalization in Northern Mozambique: the Case of Mocímboa da Praia,’ IESE Scientific Council, 2019 Over the years, this has grown into a formal and active relationship with Islamic State and its affiliates in the region. Although ACLED does not record any Allied Democratic Forces (ADF) violence in Rwanda, ADF cross-border violence into Uganda doubled in 2023 compared to the previous year. Kigali could perceive the ADF’s growing cross-border activity as a threat to its security, and involvement in Mozambique improves access to intelligence about these networks.

Unilateral operations and rebel coalitions in the DRC since 2022

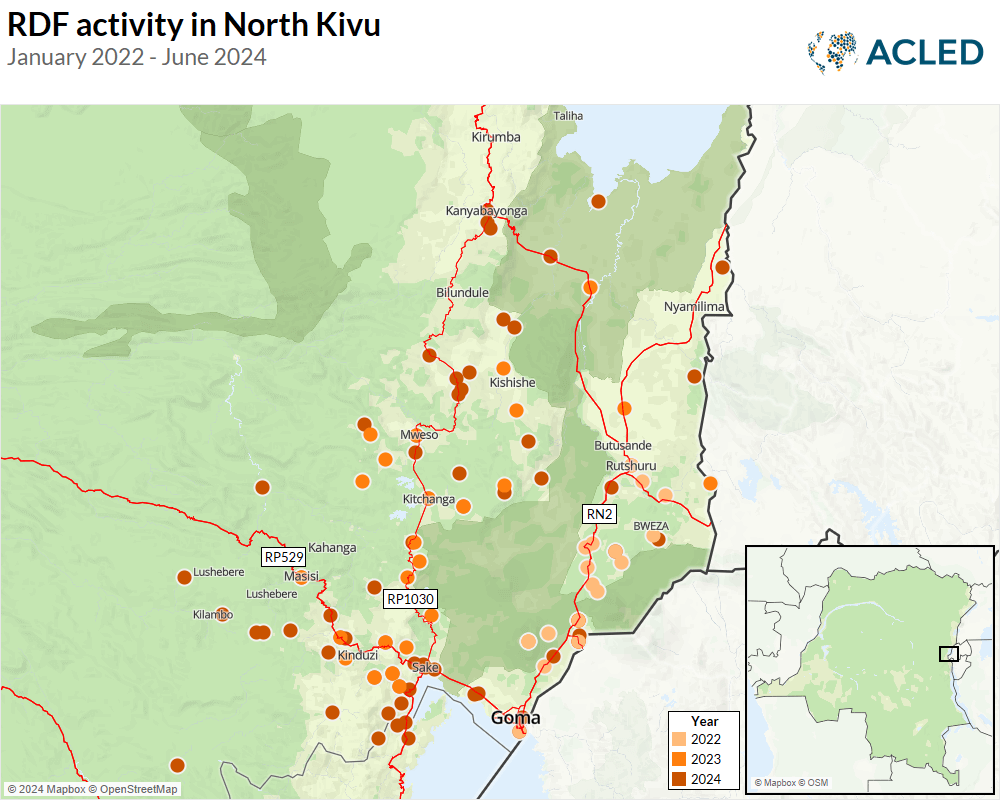

The RDF’s direct involvement in eastern DRC rose in 2022 in conjunction with an offensive launched by the M23 rebel group in North Kivu. The UN Security Council estimates that Rwanda has deployed between 3,000 to 4,000 soldiers to the DRC, operating alongside M23 rebels.59Africa News, ‘Angola announces ceasefire deal between DR Congo and Rwanda,’ 13 August 2024 Rwanda’s intervention in the DRC has likewise grown over time. ACLED data show that events involving the RDF in the DRC grew from an estimated 60 in 2022 and 2023 combined to over 150 violent events in the first six months of 2024.60According to ACLED data, based on nearly 100 international, national, subnational, new media, and other sources covering the DRC.

The relationship between Kigali and Kinshasa since the First Congo War began in 1996 has been ambivalent, swinging between cooperation and competition. On several occasions, Congolese military forces have collaborated with the RDF. For example, they participated in a joint operation in 2009 against the FDLR61UN Organization Stabilization Mission in The DR Congo, ‘Foreign Armed Groups,’ accessed 12 June 2024 — a rebel group that now has integrated several factions but traces its roots to the Interahamwe, a Hutu militia that initially carried out violence in Rwanda before fleeing to the DRC, and former Rwandan soldiers from the previous regime. However, relations have also turned conflictual several times. After the Rwandan military’s initial support for former President Joseph Kabila to take over the DRC from Mobutu Sese Seko, relations deteriorated as Kabila sought to consolidate sovereign control over the country and pushed Rwandan troops out in July 1998.62Jason Stearns, ‘The War That Doesn’t Say Its Name: The Unending Conflict in the Congo,’ Princeton University Press, pp. 57-90, 1 February 2022 Instead of expulsion, Rwanda launched renewed offensives into the DRC against the Kabila regime, clashing with military forces under the regime Rwanda had just helped install. While reaching peace agreements in 2002, fragile relations ruptured. The origins of the M23 date back to the challenges of integrating Rwandaphone militants during the conclusion of the Congo Wars.63Maria Eriksson Baaz and Judith Verweijen, ‘The Volatility Of A Half-Cooked Bouillabaisse: Rebel-Military Integration And Conflict Dynamics In The Eastern DRC,’ African Affairs, October 2013 A rebel group and precursor of the M23 eventually formed, called the National Congress for the Defence of the People, with Rwandan government support and under the leadership of a former RPF militant, Laurent Nkunda.64Jason Stearns, ‘From CNDP to M23: The Evolution of an Armed Movement in Eastern Congo,’ Rift Valley Institute, 2012 Later, Rwanda’s support of the M23 rebel group during their offensive in the DRC’s east in 2012 saw the capture of the North Kivu provincial capital, Goma.65Human Rights Watch, ‘DR Congo: M23 Rebels Committing War Crimes,’ 11 September 2012

The RDF’s involvement in the M23 conflict

As has been the case since the Congo Wars, the majority of the RDF’s engagement in violence since 2022 has involved battles against other armed groups — comprising 81% of total violent events. More than 90% of RDF operations in the DRC between 2022 and 30 June 2024 were carried out with the M23, with additional partnerships including the Congo River Alliance — a rebel group formed in late 2023 and headed by the former president of the DRC’s electoral commission, Corneille Nangaa.66Actualite, ‘Alliance Fleuve Congo : le gouvernement congolais attend toujours des explications du Kenya sur la création sur son sol d’un mouvement armé visant à “attaquer militairement” la RDC,’ 26 December 2023

ACLED records 20 cases of the RDF targeting civilians between 2022 and the first six months of 2024, resulting in over 45 reported fatalities, but over half of these events took place in 2024. While the RDF has been more careful to guard against civilian targeting during multilateral and bilateral deployments, civilian targeting now accounts for 10% of its total political violence in the DRC.

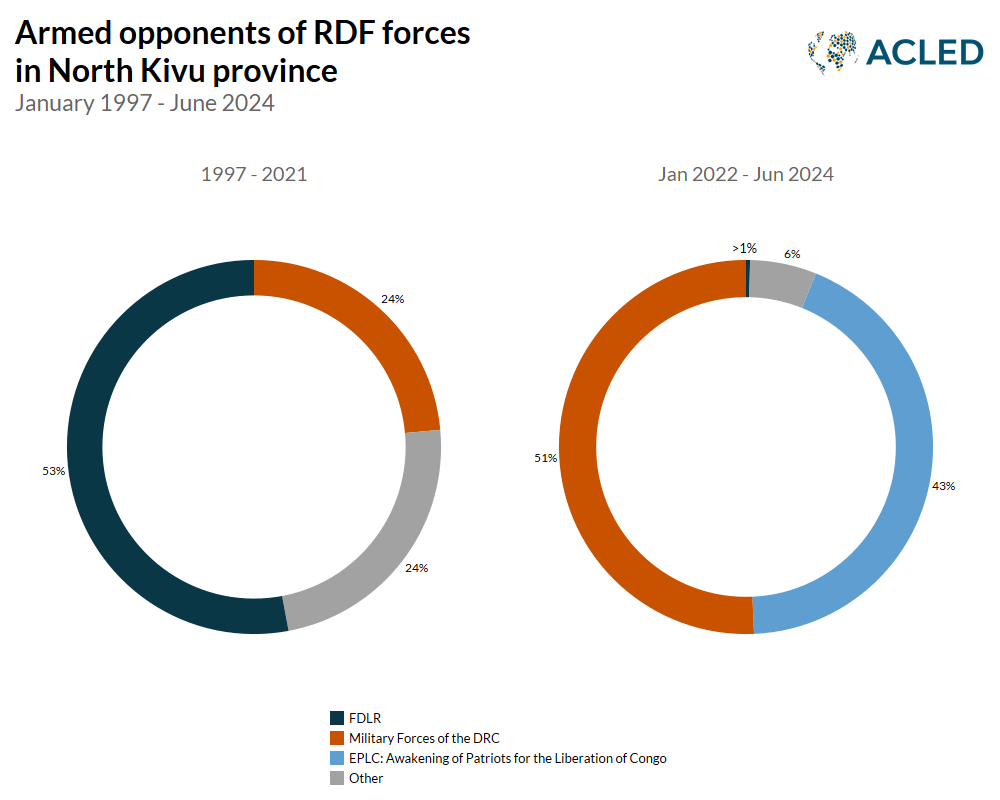

While the primary type of violence in the form of battles remains broadly consistent over time, the primary opponent to the RDF has dramatically changed (see graph below). As far back as the Congo Wars, Rwanda’s military primarily engaged with a number of rebel groups, militias, and other foreign militaries. While previous incursions have rarely seen the RDF involved in clashes with Congolese military forces, Rwanda’s primary opponents since 2022 have been FARDC and allied forces such as the Wazalendo. During this time, the RDF has seldom engaged in violence against rebel groups or militias aside from allied groups fighting with FARDC. Despite the political rhetoric against the FDLR, the RDF has not engaged directly with the FDLR since a single operation in late May 2022.67Conclusions about the lack of direct contestation between RDF and FDLR must consider that the FDLR and M23 have clashed on numerous occasions since 2021. Given Rwanda’s support of the M23, these may be taken as an indirect way for Rwanda to combat the FDLR. Further, the integration of FDLR fighters into the FARDC and Wazalendo coalition makes discerning specific FDLR militants challenging unless they are engaging in violence as a separate unit.

In addition to clashes with military forces and allied groups, Rwanda has increasingly been using shelling and artillery strikes in the DRC. Remote violence events involving the Rwandan military and M23 especially increased in the first half of 2024. A growing number of reports detail Rwanda’s provision of heavy weapons to M23, including drones, anti-drone jamming equipment, surface-to-air missiles, and anti-tank grenade launchers.68Africa Defense Forum, ‘Drones, Heavy Weapons Dominate DRC’s Fight With M23,’ 28 May 2024 Rwanda claims that the Congolese import of fighter drones and violations of Rwandan airspace require that Rwanda ensure its air defenses, serving as an indirect justification for the recent rise in remote violence.69Rwanda Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation, ‘Rwanda Clarifies Security Posture,’ 18 February 2024

Amid the rise in remote violence, civilian targeting by the RDF has also escalated, driven by increased shelling into civilian-populated areas. ACLED records 20 cases of the RDF targeting civilians between 2022 and the first six months of 2024, resulting in over 45 reported fatalities, but over half of these events took place in 2024. While the RDF has been more careful to guard against civilian targeting during multilateral and bilateral deployments, civilian targeting now accounts for 10% of its total political violence in the DRC. The RDF provision of more advanced weapons systems to the M23 has also resulted in a rising civilian toll. Civilian targeting through remote violence by the M23 — without direct collaboration with the RDF — rose from just six events in 2022 and three events in 2023 to 34 events in the first six months of 2024. Thus, the RDF’s direct military involvement in the DRC not only poses further threats to civilians but increased risks through indirect support for M23 rebels.

Squeezing Goma: Rwandan economic interests across the border

Since 2022, the RDF has sought to surround Goma and gain control of the major roadways to the regional capital. The contestation and control over these areas have severely limited military supplies and the flow of economic goods to Goma, permitting the M23 and RDF to extract revenues from imposing roadblocks along roadways and accessing mining sites.

With M23 fighters, the RDF gained control of sections of each major road linking Goma with the rest of the North Kivu region. The concentration along these roadways has especially been the case in 2023 and so far in 2024, as 48% of political violence events involving the RDF took place along the three major roads out of Goma via Sake. The M23 and RDF control of roadways also extends to other areas, such as the stretch of road between Rutshuru and the border town of Bunangana. The M23 and RDF secured several positions along this roadway in 2022, with estimated earnings of US $27,000 per month.70International Peace Information Service, L’Association pour le Développement des Initiatives Paysannes, Danish Institute for International Studies, ‘Le M23 “Version 2”: Enjeux, motivations, perceptions et impacts locaux,’ p. 5, April 2024

The movement of the RDF and support for M23 permitted the capture of several roadways and mining areas. In 2022, RDF offensives initially focused on the border region of Rutshuru, just across from northwestern Rwanda (see map below). In 2022, 67% of violent engagement took place in Rutshuru territory, followed by 29% in Nyiragongo territory — important areas of resource supply chains and links to the regional hub of Goma city along the RN2 (Rutshuru-Goma) roadway. In 2023, direct violence by the RDF began shifting to Masisi territory, a resource-rich area with three major interior roadways out of Goma via Sake. These roadways include the RP1030 (Sake-Kitchanga-Kanyabayonga), which provides the only major alternative route to the RN2 northward toward Ituri province; the RP529 (Sake-Walikale), a key route into the interior from Sake to Walikale that connects to the RN3 (Bukavu-Walikale-Kisangani); and along the southbound RN2 (Sake-Miti) from Sake toward Bukavu which is home to large reserves of coltan.71International Peace Information Service, ‘Carte de l’exploitation minière artisanale dans l’Est de la RD Congo,’ accessed 5 February 2024 So far in 2024, the RDF has increasingly moved toward Goma alongside M23 fighters, cutting off several sections of the roads near the city — especially around Sake. The busy Sake-Kilolirwe-Kitshanga road axis has an estimated revenue generation of $69,500 per month just in vehicular taxes.72IPIS, ASSODIP, and DIIS, ‘Le M23 “Version 2”: Enjeux, motivations, perceptions et impacts locaux,’ p. 5, April 2024

The making of a regional security actor

The space for multilateral peacekeeping will likely shrink in the coming years, with several peacekeeping drawdowns completed or in progress in Africa. Rwanda will likely continue to make peacekeeping contributions that provide it with strategic diplomatic and economic advantages. These are especially useful while Kigali faces mounting criticism over the violence in North Kivu. However, multilateral operations in Africa may continue at a smaller scale in the form of more regional agreements, such as the recent use of the East African Community or SADC mission in Mozambique.

Following peace agreements between Rwanda and the DRC for a ceasefire beginning 4 August 2024, political violence involving the RDF may diminish in the coming months. Past peace agreements have temporarily limited violence but have yet to effectively generate a durable solution to the contestation.

Although multilateral operations are poised to decline in the future, Rwanda already plans to send an additional 2,000 troops to support its bilateral mission in Cabo Delgado. In 2024, the joint forces have faced increasing violence from insurgents compared to 2023.73Ian Wafula, ‘“I would be beheaded”: Islamist insurgency flares in Mozambique,’ BBC, 18 June 2024 The RDF may face further pressure as SAMIM continues to withdraw troops from Mozambique this year. New opportunities for bilateral deployments may also arise in the near future. As other states in coastal West Africa face threats from insurgent groups,74Jessica Moody, ‘How Rwanda Became Africa’s Policeman,’ Foreign Policy, 21 November 2022 Rwanda is strategically positioned to expand bilateral military agreements in the region. Benin and Rwanda have already begun discussions for RDF deployment and logistical support to combat insurgent violence in northern Benin.75Africa News, ‘Rwanda, Benin talk military cooperation over border security,’ 16 April 2023 Rwanda may fill a key security space for countries disillusioned with Western or multilateral security partners but unwilling to pivot toward Russian private military options.

Following peace agreements between Rwanda and the DRC for a ceasefire beginning 4 August 2024,76RFI, ‘M23 en RDC: la présidence angolaise annonce un accord de cessez-le-feu entre Kinshasa et le Rwanda,’ 31 July 2024 political violence involving the RDF may diminish in the coming months. Past peace agreements have temporarily limited violence but have yet to effectively generate a durable solution to the contestation. Shortly after the ceasefire announcement, M23 announced it was not part of the agreement, suggesting the rebels may continue operations.77TRT Afrika, ‘M23 says not involved in DRC ceasefire talks,’ 1 August 2024 With expansion southward into South Kivu and ongoing contestation around Goma, the violence is poised to escalate throughout the year if the peace agreements fail to provide tangible results. Further, if the M23 and RDF take over Goma, or their economic constraints on strategic roads and supply routes are sufficient to force negotiations between Kinshasa and Kigali, the violence would likely crescendo and decline. This escalation and swift end to violence involving the M23 took place in 2012, shortly after the M23 captured Goma, which forced negotiations and a peace plan with the conflict parties.78Jeffrey Gettleman, ‘Rebels Pull Out of Strategic City in Congo,’ New York Times, 1 December 2012 Despite ongoing Rwandan operations in the DRC, further unilateral deployments in the Great Lakes are improbable. Skirmishes with rebel groups and border security in Burundi or Uganda are unlikely to escalate further despite diplomatic tensions.

The examination of Rwanda’s foreign military engagement illustrates the country’s shifting standing in Africa and beyond. The multilateral and bilateral deployments in the DRC and Mozambique have generally strengthened Rwanda’s status across the continent as a regional security force, bolstering diplomatic relations with the international community, working toward African integration, and pushing back against non-African interventions.79International Institute for Strategic Studies, ‘Rwanda’s ambitions as a security provider in Sub-Saharan Africa,’ November 2022; Federico Donelli, ‘Rwanda’s New Military Diplomacy,’ Institut français des relations internationales, N.31, 2022 Yet, Rwanda’s deployment into the DRC has strained relations with Kinshasa, Gitega, and Western governments. Burundi and Rwanda’s borders remain closed with frequent critical rhetoric,80Cristina Krippahl and Isaac Kaledzi, ‘Burundi-Rwanda tensions rise amid border reclosure,’ Deutsche Welle, 17 January 2024 amid growing Western hesitation to renew support for Rwandan military operations.81Romain Gras, ‘EU divided over financial support for Rwandan intervention in Mozambique,’ The Africa Report, 31 July 2024 Rwandan support for the M23 may have strained numerous diplomatic relations,82Insecurity Insight, ‘The Deployment of East African Community Forces in Eastern DR Congo,’ February 2023; Lucy Fleming and Didier Bikorimana, ‘Two armies accused of backing DR Congo’s feared rebels,’ BBC, 9 July 2024 but the growing security gap in Africa and threat of Russian influence will likely continue to make the RDF a preferred alternative for multilateral and bilateral military cooperation in the region.

Visuals produced by Christian Jaffe.