Q&A with

Aaron A. Aambo, Dr. Eleanor Beevor, Dr. Manu Lekunze & Dr. Ladd Serwat

Conflict Incident Monitor at Reach Out Cameroon, Senior Analyst at GI-TOC, International Security Analyst at the University of Aberdeen and Africa Regional Specialist at ACLED

Anglophone armed separatist groups in Cameroon are deeply engaged in illicit activities to finance their rebellion, along with the rising use of violence against civilians. In the first six months of 2024, the Northwest region is the second most dangerous administrative region for civilians in Africa, only surpassed by al-Jazirah state in central Sudan. The groups’ engagement with illicit economies includes the extensive use of abductions for ransom — one of the many practices that put civilians at risk. In this Q&A, based on our recent webinar, ACLED’s Africa Regional Specialist Dr. Ladd Serwat, the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime’s Senior Analyst in the West Africa Observatory Dr. Eleanor Beevor, Dr. Manu Lekunze, Lecturer at the University of Aberdeen, and Aaron A. Aambo, Conflict Incident Monitor at Reach Out Cameroon discuss the operations and organization of Ambazonian separatist groups in the Anglophone region of Cameroon.

How did the violence in the Anglophone regions begin, and how does it affect civilians?

Aaron A. Ambo: We are facing a sociopolitical crisis turned armed insurgency that has been happening since 2016 but kicked off actively on 1 October 2017 with the unilateral declaration of the independence of Ambazonia, formerly British Southern Cameroons. At the beginning of the crisis, there was a lot of euphoria from the local population, which manifested in the large number of people who carried out peaceful demonstrations in the major cities of the Northwest and Southwest regions. But as time has passed, we have noticed a drop in this enthusiasm, which has ultimately led to a drop in funding for these actors who have resorted to other means to fund their activities.

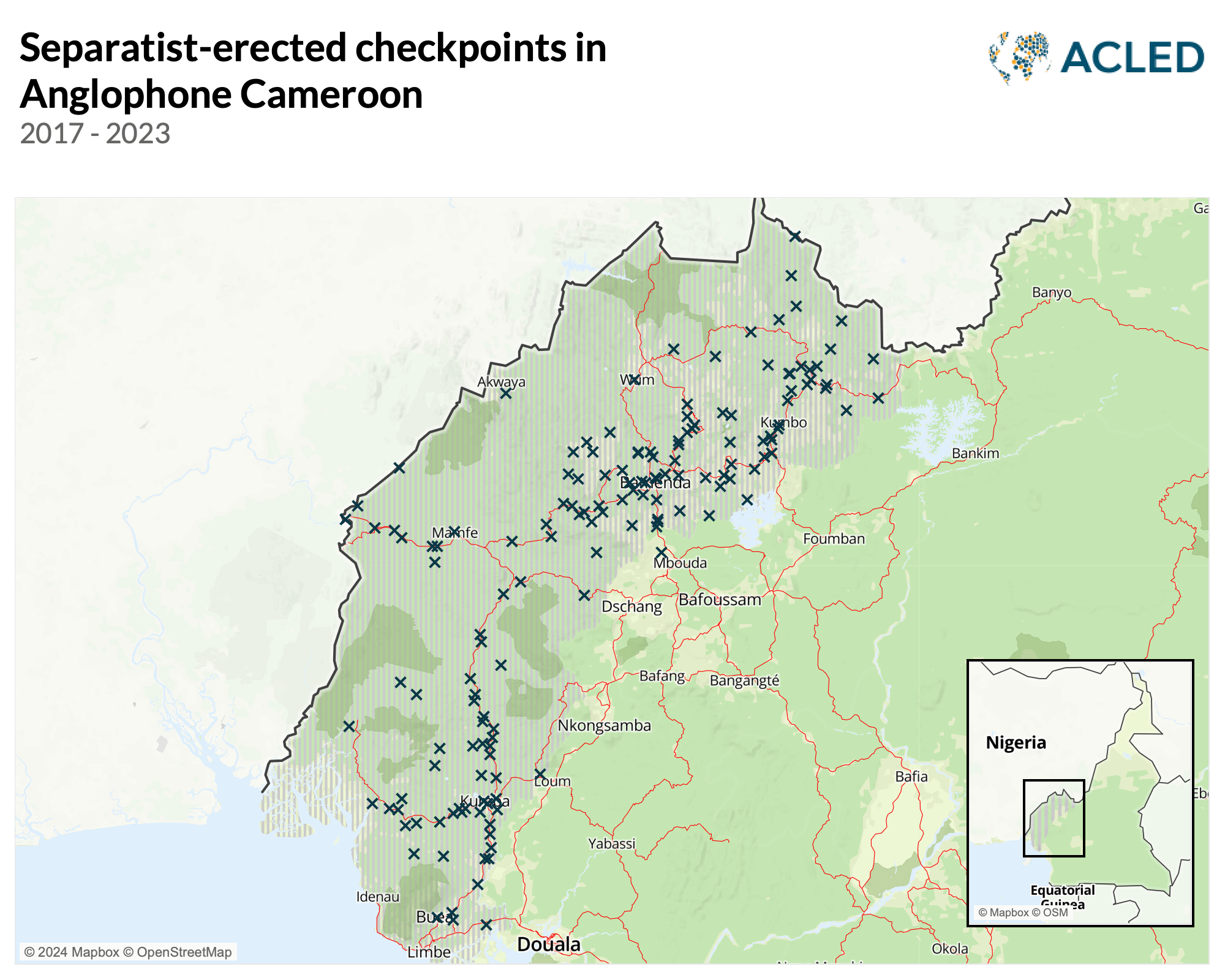

In May 2022, there was a protest in some villages, especially in Oku, against the separate fighters. Oku used to be a stronghold of separatist support in the Northwest region, so this was in stark contrast to what we saw on 1 October 2017. This reveals a drop in the popularity of armed separatist groups, which has also led to a drop in their funding. Now, they have to find alternative means of funding for their activities. Abductions for ransom are very rampant. We have the looting of property, the sale of illicit fuel, and roadblocks where they extort road traffickers by asking for money to allow them to pass (see map below).

We also have the so-called liberation tax, which has been a great source of pain and grief for civilian populations. Separatist groups issue a receipt after the tax is paid, and if you are caught without the receipt, you are in trouble. If the security forces catch you with a receipt, you are still in trouble. This means that either way, civilians end up suffering as a result. The crisis has also caused other problems that were quite latent in our communities, especially with regard to farmers and grazers. At the beginning of the crisis, the grazers, who are predominantly from the Mbororo ethnic group, weren’t in support of separatist fighters who then targeted their cattle and livestock. This forced the grazers to side with security forces, which sometimes arm them and use them as community informants. This has emboldened them to rape and attack civilians. These latent issues within our communities have been raised or caused by the crisis. Right now, we face a multifaceted crisis where we don’t just have non-state armed groups against security forces, but we have farmers against grazers, we have grazers against non-state groups, and vice versa. One of the biggest issues that has come up with regards to attributing responsibility is identifying actors. We have situations in which non-state armed groups dress in military attire and attack civilians. We have situations in which members of security forces disguise as members of non-state armed groups to extort and attack civilians, and we have situations in which common criminals have taken advantage of the situation to make money. Monitoring and documenting these incidents has become difficult because it is difficult to know who is whom, who is doing what, where, and who is responsible for what.

How has support for the separatist cause evolved, and how has it impacted its operations?

Eleanor Beevor: For those diaspora members who wanted to support the Anglophone cause, whichever way they may have interpreted that, sending money and fundraising was one of the few ways that they felt able to engage in this. The question is, what kind of relationship did this fundraising create between the diaspora and the armed groups? When you are an armed group, and you have few or no resources — you started as a very localized, perhaps village-level defense group and then find yourself up against a very well-armed opponent — you don’t say no to offers of money, even if those giving it want a degree of control in return. A lot of this was phrased in terms of solidarity, and these relationships developed quite willingly. The provision of money from the diaspora that was being transferred to some of these groups enabled individuals in the diaspora to carve out roles within the separatist conflict that looked like leadership. Money was being passed through the political wings to the armed groups, and, in doing so, organizations such as the Ambazonia Governing Council and the Interim Government were able to carve out a kind of coordination role for the armed groups on the ground. But there were also cases of individuals taking it upon themselves to fund smaller groups, particularly if they had a local connection to them. So, there were also more disparate individuals who were able to acquire at least a degree of influence, if not control, over the armed groups.

It didn’t take very long for Cameroonian security services to detect that these transfers were happening through regular money transfer services. Intelligence began following the people sent to pick up money at the transfer branches on behalf of the armed groups and then began tracking down the people involved in the financing networks, and this led to a number of arrests, at least within Cameroon. Likewise, there were new regulations placed on the use of money transfer services. So, this state-led crackdown was one important factor in reducing the flow of financial support from the diaspora to the armed groups.

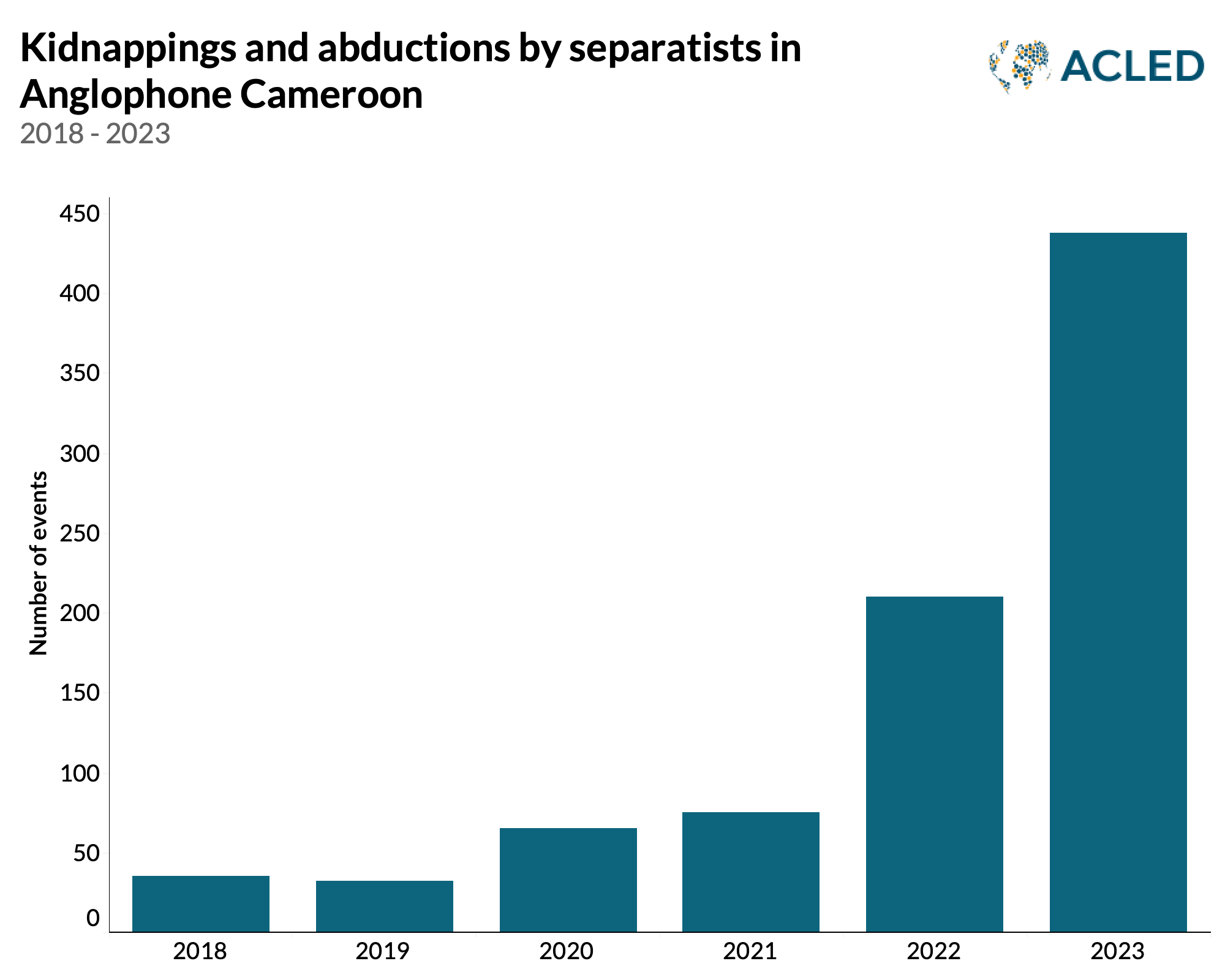

The other major factor that led to the reduction of that support was the deterioration in the behavior of many of these armed groups. The diaspora leaders were very far from the action, and they had never really been in a position to direct the day-to-day activities of these groups. They also didn’t have a great deal of authority to be able to do so. The money that they provided gave them influence but not control. One of the major factors that fast-tracked the breakdown of that influence was the kidnap for ransom by the armed separatists. You can see from this graph that there was already a small number of kidnap-for–ransom incidents cropping up in 2018 (see graph below). That’s increased every year since, particularly after 2020, and that increase reflects a vicious cycle.

Kidnap for ransom was always one of the most damaging practices in terms of the armed groups’ legitimacy in the eyes of civilians. The more that that kidnap was used, the less willing diaspora supporters were to fund the armed groups. As a result, the armed groups became more and more reliant on illicit activity for money, and that included kidnap for ransom.

Ladd Serwat: Exactly, what we have recorded at ACLED is this growth over time of violence targeting civilians by separatist groups, in turn diminishing their credibility to the diaspora and limiting the funding that the diaspora was willing to give.

From 2017-2019, civilian targeting in the Anglophone region was primarily conducted by state forces, generating legitimacy for separatist fighters as defenders of the civilian population. By 2020, separatist groups were targeting civilians in at least equal proportion to state forces, and then in recent years, we have seen an exponential rise in separatist violence targeting civilians, using a lot of the tactics Nella has just mentioned.

Eleanor Beevor: When kidnapping, ransoms are generally paid out in varying quantities, but they’re generally not particularly high. They usually come in under 1,000 US dollars, which means that fighters compensate for these relatively low payments with quite a high number of kidnaps.

Certainly, there were also bandit groups, and you could call them semi-professional kidnappers, who took advantage of this instability and used it as a cover for their own activities. It’s also true that there have been cases of diaspora leaders encouraging the kidnap of people who they saw as disloyal to the cause, so it would be wrong to present this as a problem that was purely local to Northwest and Southwest Cameroon. Nevertheless, kidnapping was really important in the breakdown of trust between many of the separatist armed groups and the pro-separatist members of the diaspora.

How much do the demands for various payments impact the day-to-day of people in the Anglophone regions?

Eleanor Beevor: It is something that really affects civilian life at the moment, and it’s also important because it has major implications for armed group legitimacy. Separatist groups demand tax or contributions — they might use lots of different words like liberation tax — from civilians in almost every aspect of their lives, and it’s summed up quite nicely in the quote from this fighter:

“Sometimes we mount roadblocks and drivers have to pay as they go in and out. This to us means they identify with the cause. Those living out of the village that come for ceremonies — for example, funerals or weddings — they give money. Trucks exporting food crops from the village, like Irish potatoes or coffee beans, must pay a levy. This money we use first for our upkeep, for example to buy bathing supplies, toiletries. We share some of these funds to go to town and relax. Importantly, we use the money to pay for the fabrication of local guns and bullets. And we buy motorbikes for our movements and fuel.”1Interview with an Ambazonian separatist fighter from Kom, Douala, 25 July 2023

You have tax on road transport, social events, food crops, and service provisions not directly provided by fighters but taxed nevertheless. When these taxes or contributions are demanded, they’re framed in a way as a measure of support for the war effort. As you can see here, he says this giving of money means that they identify with the cause. This puts civilians in an extremely difficult position. If they aren’t able to give it, or they refuse to, there is a risk that they will be identified as someone who isn’t supportive of the cause, potentially a collaborator or a traitor — someone who can come to be known as a ‘black leg.’ Being identified as this can have very violent and even deadly consequences for the accused. So, while there might still be genuine supporters of some of these armed groups and contribute freely, there will also be a huge majority who feel that they have no choice but to give out this money.

Do you find that there’s a gendered aspect to the illicit economy and extortion? Are there any cases of women acting as leaders in this illicit economy?

Eleanor Beevor: The illicit economy certainly in the Northwest — and I can speak more confidently about the Northwest than the Southwest here — is not something that necessarily needs leaders. It’s what is often referred to as the ant trade. It’s the very mundane everyday smuggling by small groups or organizations of people crossing the border on a daily basis, mostly carrying quite mundane goods. The major component of the illicit economy is smuggled fuel brought over from Nigeria. The Northwest region of Cameroon has few, if any, operational filling stations under statutory recognition by Yaoundé. As a result, smuggled fuel is the only source available. This makes for a very big illicit economy.

While the gendered aspect of that wasn’t a central question of our work, one thing that was made quite clear to us was the importance of women in that fuel trade. One of the complicated aspects of illicit economies is that they have been really important in terms of supporting families when there are very few other sources of formal employment available.

More broadly, in terms of the conflict, we did hear a lot about how women had taken on some quite important roles within Ambazonian separatist groups themselves. They were seen as less likely to come under suspicion, so they were often used as intelligence gatherers.

Aaron A. Ambo: I think there’s something we left out with regards to illicit economies: the sale of marijuana, which is quite rampant in communities, especially in the Bui division. It is a commonly grown drug in that part of the country, and separatist fighters have kind of taken over the production. One thing I witnessed myself in Oku is that the women grow cannabis inside cassava farms. The cannabis leaves are very similar to cassava leaves, so it helps dissimulate them. I witnessed this when I was abducted in 2022 by separatist fighters. Some of the fighters are married, and their wives play a role in growing the cannabis plants that they intend to sell to raise money.

Where are most of the separatists’ weapons coming from?

Eleanor Beevor: The most common source of arms for separatists has been Nigeria. There’s been a lot of small-scale arms transfers. We have a few stories in the report of, for instance, a small number of firearms being hidden in the backs of motorbikes. There are a lot of trucks going over the Nigerian border because it’s a very important supplier of all sorts of consumer goods for Cameroon, so it’s very easy, given that it’s a very porous border, for arms to be stashed within those movements. What we know is that Nigeria has plenty of quite well-organized arms traffickers who may have had roles in this, but there’s also plenty of room for more opportunistic purchases of arms on a kind of more ad hoc basis.

Manu Lekunze: Because of all the problems that Nigeria has, it’s a lot easier to smuggle arms through Nigeria. And because of the long border between Nigeria and Cameroon, it’s much easier to smuggle arms from Nigeria into different parts of Cameroon. But not from the Nigerian government or any government I have evidence of. It’s mainly clandestine organized crime networks across the Sahel.

What does the proliferation and fragmentation of these groups, as indicated in the report, tell us about violence in the Anglophone region and prospects for resolution of the conflict?

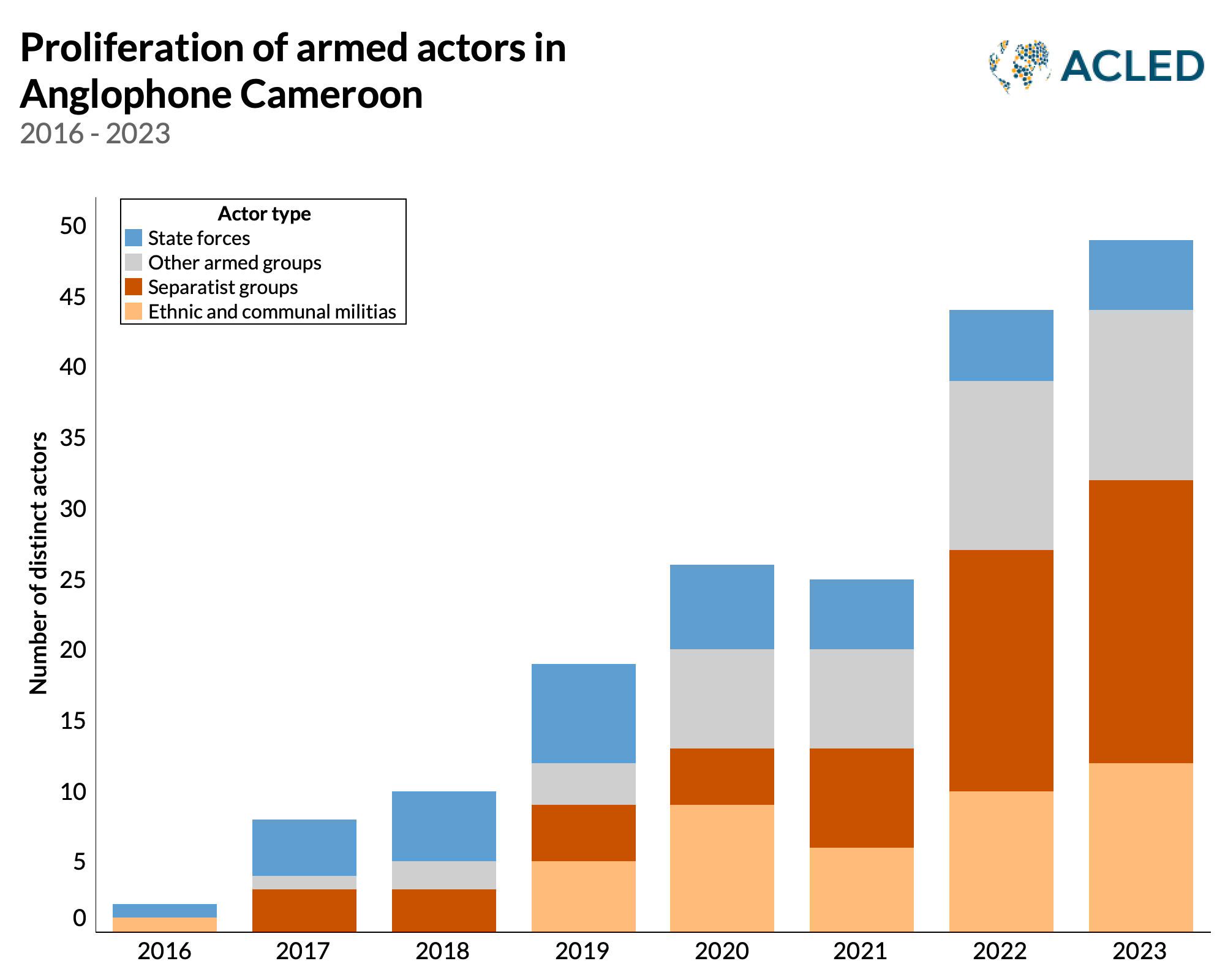

Ladd Serwat: While there are still separatist groups that promote a unified Anglophone Cameroon and independence — such as the Ambazonian Interim Governments — an increasing number of separatist groups (see graph below) now compete less for independence and more for control of local areas. Amidst the fragmenting conflict, there has especially been growth in community self-defense groups taking up arms to defend themselves, whether against separatists, the state, or other armed groups. Aaron also touched on the rise of ethnic militias, such as the arming of various Mbororo groups. While some of these groups collaborate when interests align, ACLED data also show an increasing amount of infighting amongst and between separatist groups, often trying to control smaller areas. Coupled with the rise in civilian targeting, separatist interests appear to be moving away from the independence of the region and towards self-preservation through more localized interests and engagement in illicit economic activity.

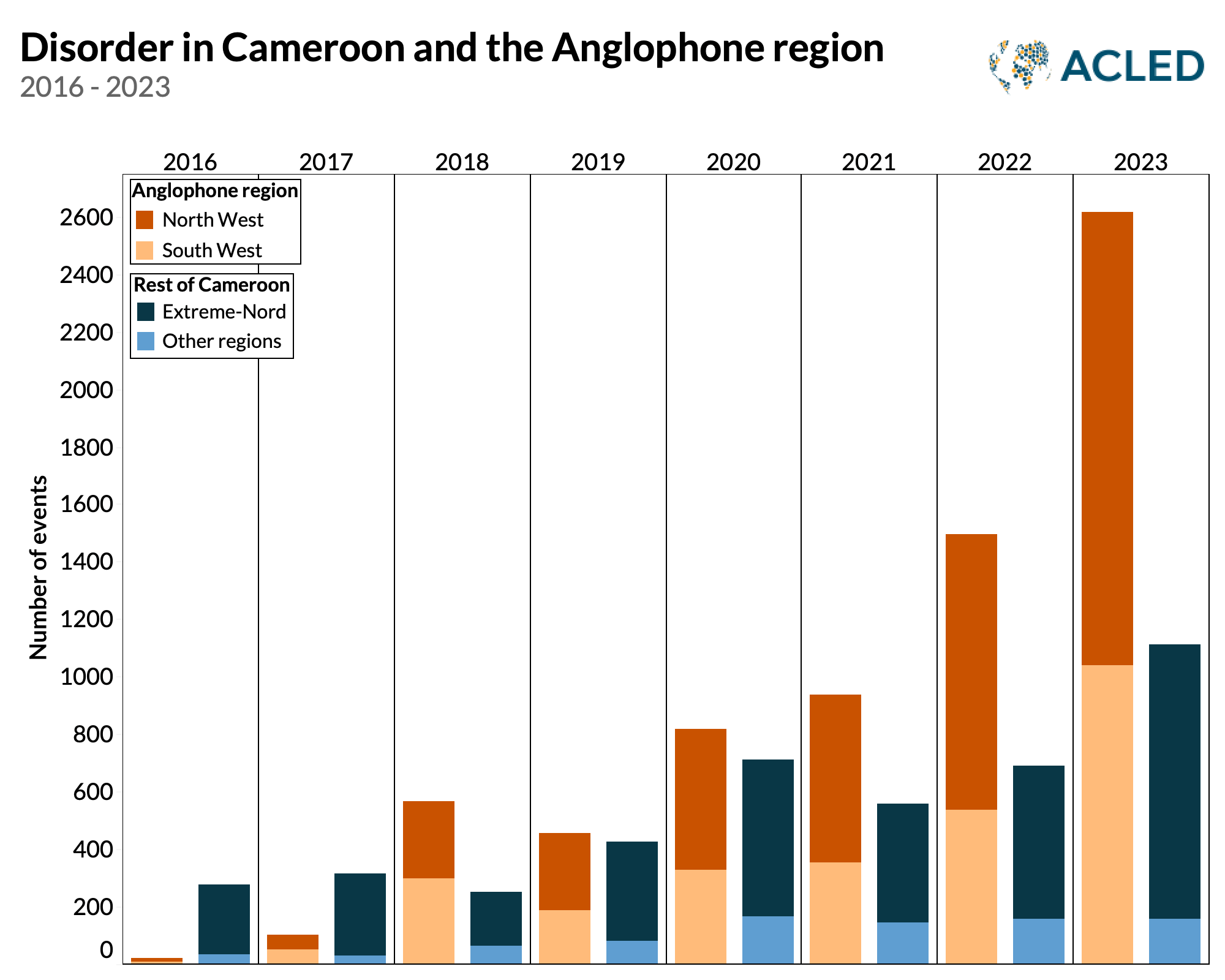

We can see this translate into the breakdown between the Northwest and Southwest regions compared to the rest of Cameroon (see graph below), concerningly shifting more and more toward the Northwest region of Cameroon.

Violence in the entire Anglophone region has also been building in 2024. The second quarter of 2024 was actually the most violent of the conflict so far. So while we don’t have annual data for this yet, what we can see is that conflict is escalating and that the fragmentation of this conflict is increasing the levels of violence but it’s also weakening the bargaining position of the separatist movement, which I think makes peace negotiations more difficult. There are more groups with more competing interests so bringing those groups to the table can be quite challenging. Many of the peace negotiations so far have tried to bring in much of the diaspora and while I think that is still important, the localization of leadership within the separatist movement will likely require further engagement with local organizations and these local leaders in order to make mediation possible — if that is possible.

This Q&A is based on ACLED’s webinar briefing on Anglophone separatists in Cameroon, which was held on 10 September 2024 and can be watched in full on ACLED’s YouTube channel. The text has been edited for length and clarity.