Situation Update | October 2024

The deputy president’s impeachment triggers unrest in Kenya

17 October 2024

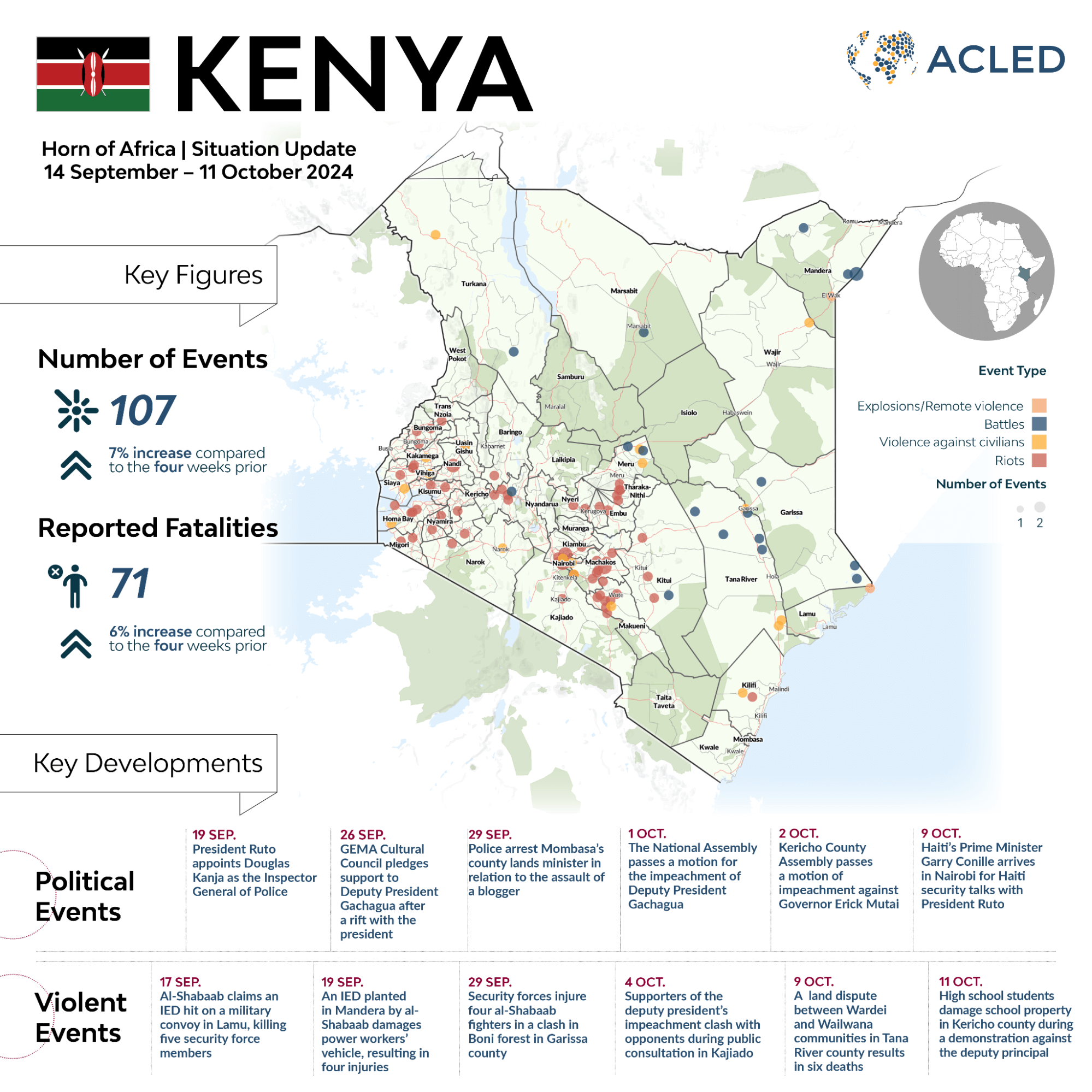

Kenya at a glance: 14 September to 11 October 2024

VITAL TRENDS

- From 14 September to 11 October 2024, ACLED records 107 political violence events and 71 reported fatalities in Kenya. Most events took place in Makueni, which saw nine political violence events that were mainly linked with mob violence.

- Tana River and Meru counties had the highest number of reported fatalities, with 20 reported in Tana River and eight reported in Meru. Most of the fatalities in Tana River were linked to clashes between suspected Wardei and Wailwana ethnic militias over land disputes.

- The most common event types during the reporting period were riots, with 69 recorded events, followed by violence against civilians and battles, each with 18 recorded events. The majority of riots were in Makueni and Machakos counties, each with eight recorded events.

The deputy president’s impeachment triggers unrest in Kenya

Kenya faced considerable unrest in September and October. One element of this was the impeachment process taking place against Deputy President Rigathi Gachagua, which was catalyzed by the response of President Wiliam Ruto to the Gen Z protests of June and July. His decision to seek the support of Raila Odinga’s Orange Democratic Movement (ODM) was followed by a heightening of tensions with his deputy president, culminating in impeachment proceedings alleging corruption, undermining of the National Intelligence Service, and tribalism.1The Republic of Kenya, ‘Notice of Special Motion by Hon. Mutuse Eckomas Mwengi, Member of Parliament, Kibwezi West Constituency, for the Removal from Office, by Impeachment, of His Excellency Rigathi Gachagua, EGH, the Deputy President of the Republic of Kenya,’ 27 September 2024 While the impeachment of a deputy president is unprecedented under the current constitution, impeachment is not unusual in Kenya. In the same week, it considers the impeachment of Gachagua, the Senate rejected an impeachment motion concerning Governor Erick Mutai of Kericho county, while Governor Kawira Mwangaza of Meru continues to fight her August impeachment through the courts.2Parliament of Kenya, ‘The Senate set to begin impeachment proceedings against Kericho governor Mutai,’ accessed on 14 October 2024; Richard Munguti, ‘Court extends orders suspending impeachment of Mwangaza,’ The Nation, 9 October 2024

Parallel to impeachment proceedings, Kenya continues to face the long-standing issues of violence in schools. While arson in the country’s schools has attracted much attention, this is just one aspect of disorder in schools, with student-led demonstrations remaining a frequent occurrence. Also persistent is al-Shabaab’s continued attacks on civilians and security forces, which reached new highs for 2024 in August and September.

Impeachment process sparks unrest

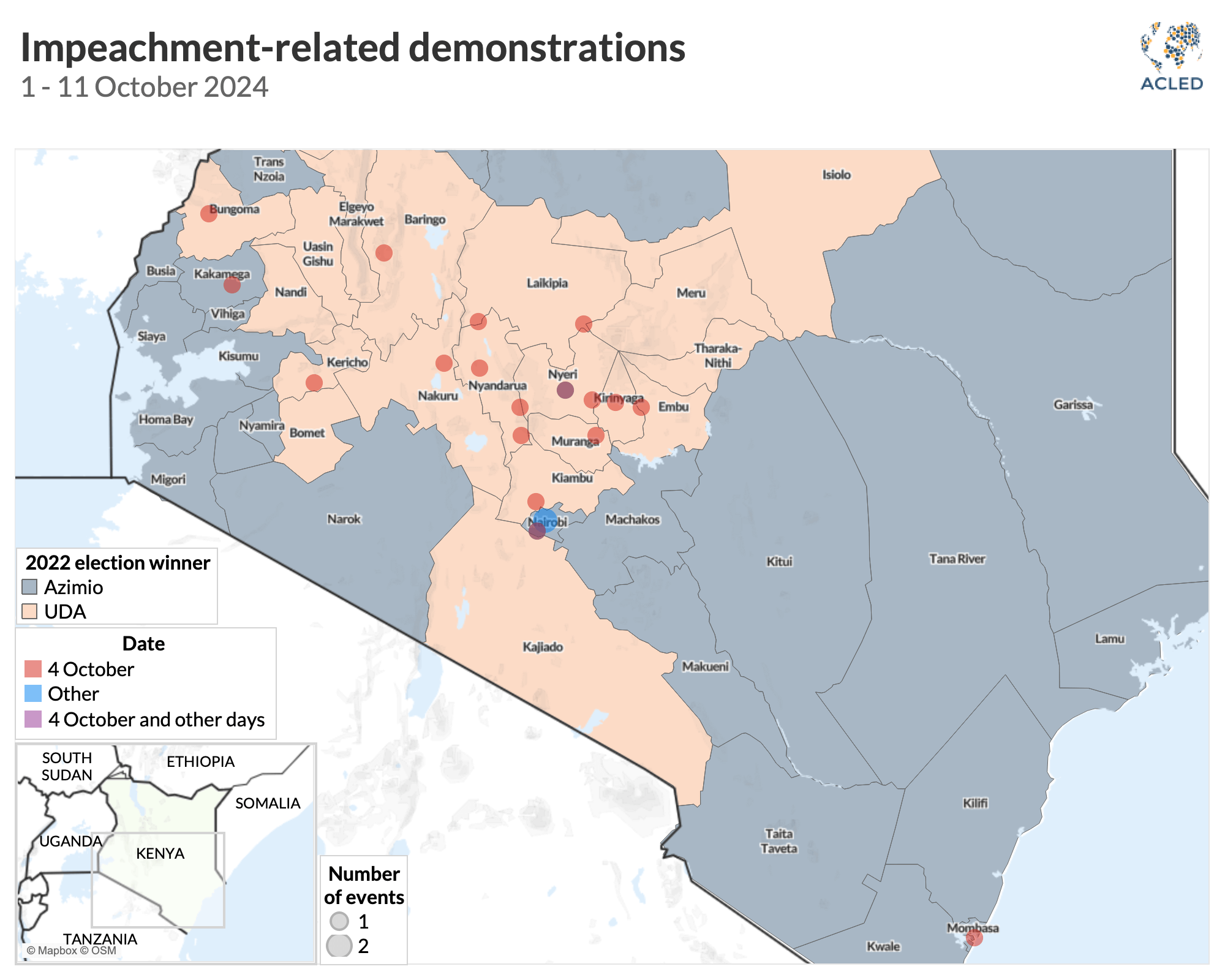

ACLED records 22 demonstration events related to the impeachment proceedings against Gachagua in October. Eighteen of these incidents occurred on 4 October, during public participation exercises instigated by parliament to elicit citizens’ views on the charges Gachagua is facing (see map below). Of those 18 events, most were in support of the deputy president, of which 14 were peaceful. Nevertheless, the geographic spread of the events and the organization required indicate that Gachagua and his supporters have the capacity to generate widespread and potentially sustained unrest.

The demonstrations, likely organized and funded by Gachagua’s camp, illustrate the fragility running through Kenya’s coalition politics. Most demonstrations occurred in counties that voted for Ruto’s United Democratic Alliance (UDA) in 2022, reflecting the rift in the Kenya Kwanza coalition. Gachagua’s principal role in the UDA was to bring the Gikuyu, Embu, and Meru communities into Ruto’s political camp following Ruto’s fallout with his predecessor, President Uhuru Kenyatta, whom he served as deputy president. The rift between Ruto and Gachagua became acute when the Gen Z protests broke out, and Gachagua’s allies were accused of inciting some of the unrest, while Gachagua blamed the National Intelligence Service for not foreseeing the unrest.3Stephen Letoo, ‘DP Gachagua Aides Grilled For Allegedly Sponsoring Goons During Gen Z Protests,’ Citizen Digital, 30 July 2024; Bashir Mbutiia, ‘Gachagua Demands NIS Director Haji’s Resignation Over Intelligence Failure Amid Finance Bill Protests,’ Citizen Digital, 26 June 2024

In responding to the Gen Z protests by forming an alliance with Raila Odinga’s ODM, Ruto has shown the continuing importance of communal politics and their strong regional bases to the shifting coalitions in Kenya. The demonstrations in support of Gachagua on 4 October illustrate his ability to mobilize support on the street. The potential for further unrest remains as the impeachment process proceeds. Even if found guilty, Gachagua may appeal to the courts, continuing the rift and opening further flashpoints for unrest.

In parliament, the impeachment process has moved quickly. On 1 October, Mwengi Mutuse, a backbench member of parliament from the ruling Kenya Kwanza Alliance, tabled the motion to impeach in the National Assembly.4The Republic of Kenya, ‘Notice of Special Motion by Hon. Mutuse Eckomas Mwengi, Member of Parliament, Kibwezi West Constituency, for the Removal from Office, by Impeachment, of His Excellency Rigathi Gachagua, EGH, the Deputy President of the Republic of Kenya,’ 27 September 2024 The motion included 11 charges, including corruption in public contracting, favoring his own Kikuyu community, and undermining government policy positions. The charges reflect a relationship breakdown between President Ruto and his deputy president. Gachagua himself outlined the extent of the rift on 20 September, accusing Ruto’s advisers and ministers of systematically undermining his authority.5YouTube @Citizen TV Kenya, ‘DP Rigathi Gachagua gets candid on what’s going on in the government [Part 2],’ 20 September 2024 On 4 and 5 October, public participation exercises were held across the country. On 8 October, the National Assembly passed the motion. Gachagua’s two-day impeachment trial in the Senate began on 16 October.6Parliament of Kenya, ‘Deputy President to face full house in impeachment trial,’ accessed on 14 October 2024 The speed of the process and the organization behind it reflect the support of the presidency.

Arson — just one expression of discontent in schools

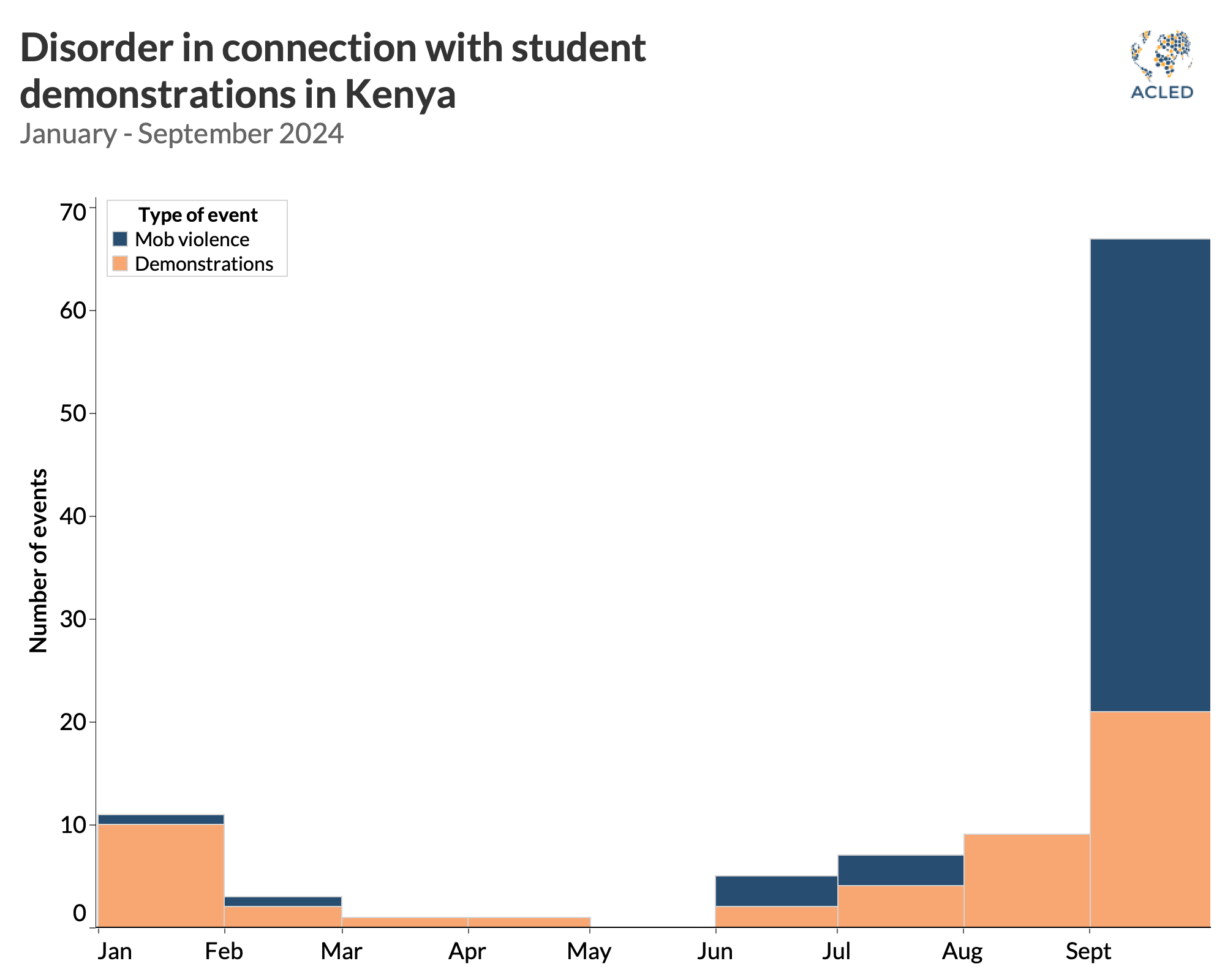

Though school fires spiked in September, they have not occurred in isolation. Demonstrations by school students, some involving violence, rose steadily from June to September and have continued into October (see graph below). Issues driving the demonstrations have ranged from concerns about corruption in school management to property speculators grabbing school land. The increasing violence in school demonstrations is reflected in the rising disorder in Kenyan political life over the past 20 years, as indicated by ACLED data from that time.

While arson at educational facilities and student demonstrations during which school property is burnt frequently occur in Kenya, these events surged throughout the country in September. ACLED records at least 46 cases of arsonists and rioters burning school property in September. These school arson attacks contributed to nearly 90 mob violence events in Kenya over September, the highest number of monthly mob violence events since ACLED began recording data on Kenya in 1997. School fires occurred across 18 counties in Kenya in September. These cases of arson sometimes turned deadly, including the burning of a dormitory at the Hillside Endarasha Academy in Nyeri county on 5 September that reportedly killed 21 students and injured at least 20 others.7David Muchunguh, ‘Uneasy silence over tragedy as Endarasha 21 are buried,’ Nation, 27 September 2024

Student strikes have been a feature of the country’s political life since the colonial era.8National Crime Research Centre, ‘Research Issue Brief into Secondary Schools Arson Crisis in Kenya,’ 2017 Independence leader Jaramogi Oginga Odinga, father of Raila Odinga, credited participation in such events for his own political formation but today’s student actions are notably more violent.9Elizabeth Cooper, ‘Students, arson and protest politics in Kenya: School fires as political action,’ African Affairs, October 2014, pp. 583-600

The school arson phenomenon is more recent, emerging around the start of the century. While perpetrators are usually unknown, evidence suggests they are most likely students. In interviews, students involved in such incidents have said that arson is a protest of choice given the low likelihood of getting caught and the attention it can bring to problems.10Elizabeth Cooper, ‘Students, arson and protest politics in Kenya: School fires as political action,’ African Affairs, October 2014, pp. 583-600

Students who engaged in arson in the past noted how their choice of protest had been informed by violent protest in the wider community.11Elizabeth Cooper, ‘Students, arson and protest politics in Kenya: School fires as political action,’ African Affairs, October 2014, pp. 583-600 Inquiries into disorder in schools have focused on arson events and their proximate causes, such as examination stress.12Republic of Kenya Departmental Committee on Education and Research, ‘Report on the inquiry into the wave of students’ unrest in secondary school in Kenya in Term 2, 2018,’ July 2019; National Crime Research Centre, ‘Research Issue Brief into Secondary Schools Arson Crisis in Kenya,’ 2017 Of at least equal concern is how students’ learned experience of violence as a political tool may shape their own future political and public engagement and public life more broadly.

Al-Shabaab remains on the front foot

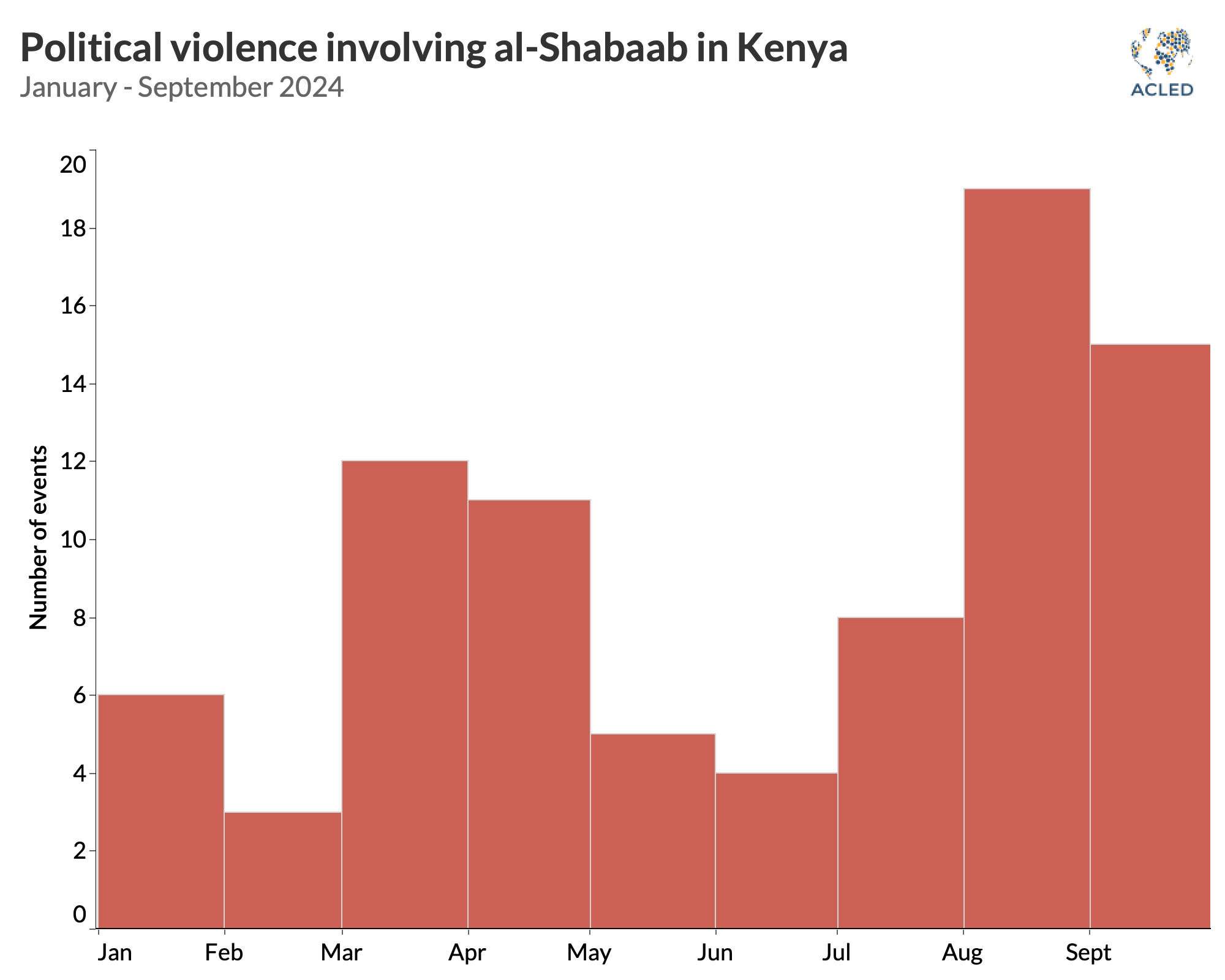

In counties bordering Somalia, recent al-Shabaab activities outnumbered counterterrorism activities by state forces considerably in recent weeks. Political violence events involving al-Shabaab reached their peak for 2024 so far in August (see graph below). ACLED records 19 events involving the group for that month. September’s 15 events were the second-highest number of such incidents for the year, with at least 14 reported fatalities. Thus far in October, the group has been involved in one incident.

In September, al-Shabaab concentrated offensive actions in Mandera county, where the group undertook nine attacks. Just one targeted civilians when, on 19 September, an IED damaged a truck carrying electrical engineers. Of the eight attacks on security forces, six were on camps or checkpoints. Al-Shabaab targeted two convoys, one with an IED and one by ambush.

In Mandera, al-Shabaab killed three members of the security forces. The most deadly attack over September and into October was in Lamu county, where the group claimed to have killed five members of the security forces with an IED attack on a convoy of vehicles on 17 September, on the road between Kiunga and Ishakani in East Lamu.

Only in Garissa has the state been on the offensive recently. ACLED records three successful security forces operations in the second half of September. On 19 September, a multi-agency security team disrupted an IED manufacturing team near Dadaab. The team escaped, though IED-making materials were seized. On 22 September, security forces seized bomb-making materials at a guest house in Garissa town. The same day, the Kenya Defence Force’s elite Long-Range Surveillance Unit attacked al-Shabaab militants on the edge of the Boni National Forest Reserve, killing at least six. One week later, on 29 September, four al-Shabaab members were wounded in an operation conducted by security forces in Boni forest. More IED-making equipment was seized, as well as weapons. Such raids are, however, of limited success, particularly when weighed against al-Shabaab’s recent activity in Mandera.