Myanmar has been mired in conflict for decades, but its direction changed dramatically after the 2021 coup and the proliferation of new armed groups resisting military rule. ACLED records over 2,600 new non-state actors participating in Myanmar’s conflict since April 2021 — accounting for 21% of all ACLED-recorded non-state armed groups worldwide. Most of these groups or their forerunners were formed by anti-coup protesters who could no longer peacefully resist the military’s increasingly systematic detention, torture, sexual assault, and killings of protesters. While many individuals consciously fled the military’s subjugation for arms training in other parts of Myanmar, local defense forces also grew organically in communities at risk of military reprisals and attacks. These groups were formed by people from all walks of life: local politicians, national party members, public servants, students, farmers, and more. After six weeks of escalating military repression, including police snipers shooting unarmed youth in the head, the first battle between the military and an armed resistance group organized by civilians was reported in Sagaing region: On 26 March 2021, the residents of Tamu town defended their protest sites with single-shot hunting rifles. The subsequent proliferation of new armed groups formed by civilians under hundreds of different local banners is now often collectively termed the ‘Spring Revolution.’1Frontier, ‘Myanmar’s Spring Revolution: a year in photos,’ 1 February 2022 The revolution has led to a new, fragmented conflict landscape in which the Myanmar military has struggled to check the advance of both new and old armed groups, and only retains control of the country through its unrivaled air power.

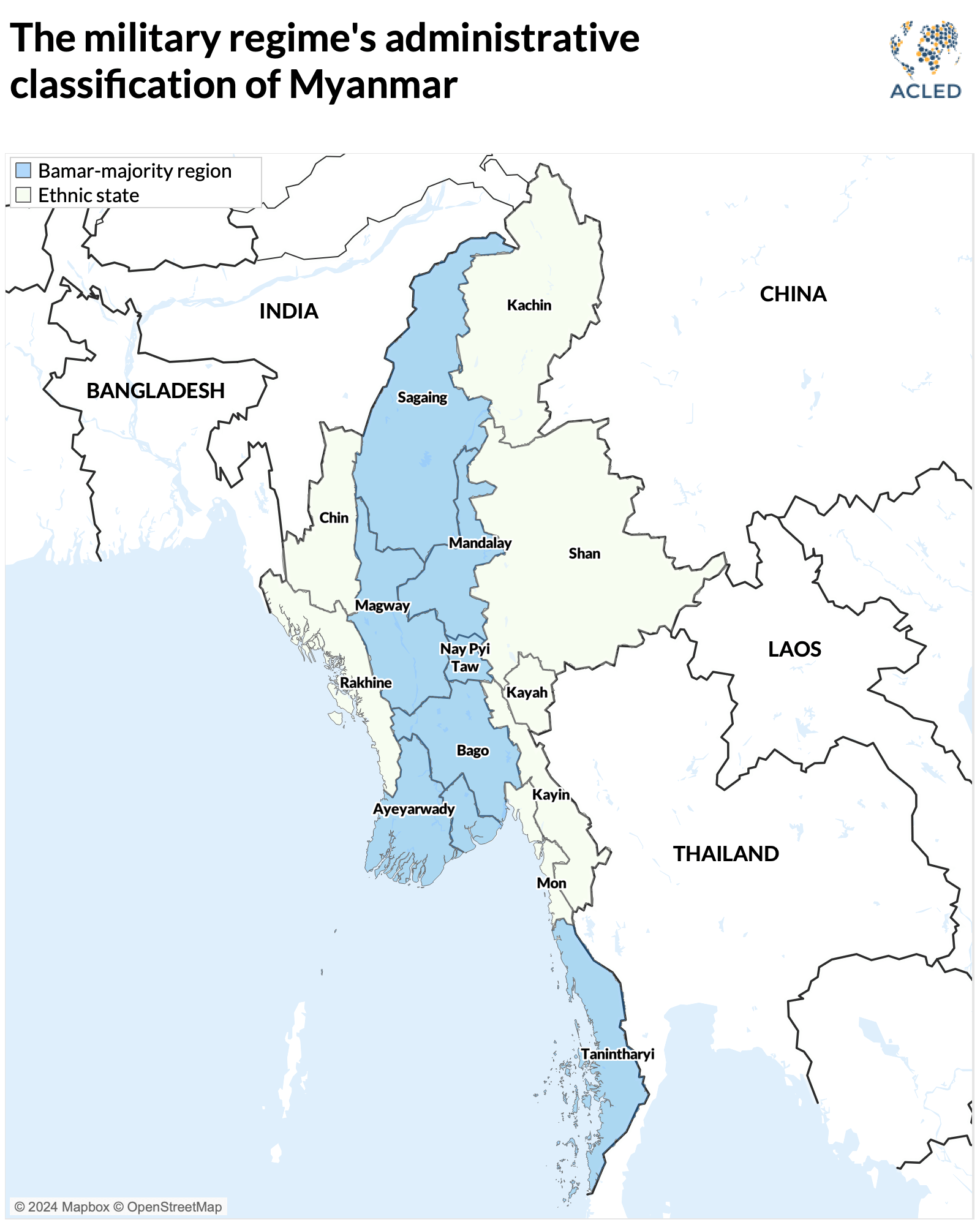

Prior to 2021, the military was in protracted wars with a smaller number of larger, well-established Ethnic Armed Organizations (EAOs), so-called because they also encompass their respective political wings. Most EAOs originally took up arms after political negotiations for power sharing and autonomy with the government of Burma and the military failed.2David Brenner, ‘Ethnonationalism and Myanmar’s future,’ New Mandala, 18 September 2024 EAOs primarily operate in the ethnic states of Myanmar, administrative territories named after some of the country’s ethnic groups, which all have international land borders. They have rarely operated in the six regions in central Myanmar which are predominantly populated by the majority Bamar (Burman) ethnic group (see map below). Before 2021, territorial exchanges between the military and armed organizations were rare. The military’s divide-and-rule strategy kept it in firm control of state power in most of the country, and the majority of armed conflict was in the ethnic states and border areas with these EAOs. But since 2021, increasing coordination and cooperation between established EAOs and the newer resistance groups has led to a situation where the military now controls less territory than at any time since it first forcibly took control of the country in 1962.

While short-term operational coordination between these groups has led to notable success, more advanced cooperation remains nascent and fragile. If such coordination does not deepen into cooperation, the kinds of further victories needed to force the military into negotiations or defeat are unlikely. This could result in a prolonged conflict where civilians continue to suffer from military repression and widespread displacement. Most EAOs and newer resistance groups share the common goal of overthrowing military rule, but their differing strategies and political visions can lead to competition and even open conflict between them. Shan EAOs, such as the Restoration Council of Shan State/Shan State Army-South (RCSS/SSA-S) and Shan State Progress Party/Shan State Army-North (SSPP/SSA-N), have a long history of vying for territory in Shan state, and tensions are high among some newer resistance groups in Chin state and Sagaing region.

This report unpacks the proliferation and realignment of armed resistance groups fighting the military since 2021, exploring how their fragmented position poses significant challenges and opportunities for conflict mitigation and resolution. First, it details the dynamics between resistance groups and established EAOs, including how their objectives and operations differ and align. Then, it discusses how limited cooperation among armed resistance groups prevents effective protection of civilians from military abuses, before delving into case studies of violent competition between groups in Shan state, Chin state, and Sagaing region. Finally, the report outlines the potential in the future for both coordination and competition between armed groups in Myanmar.

Cooperation of old and new resistance groups

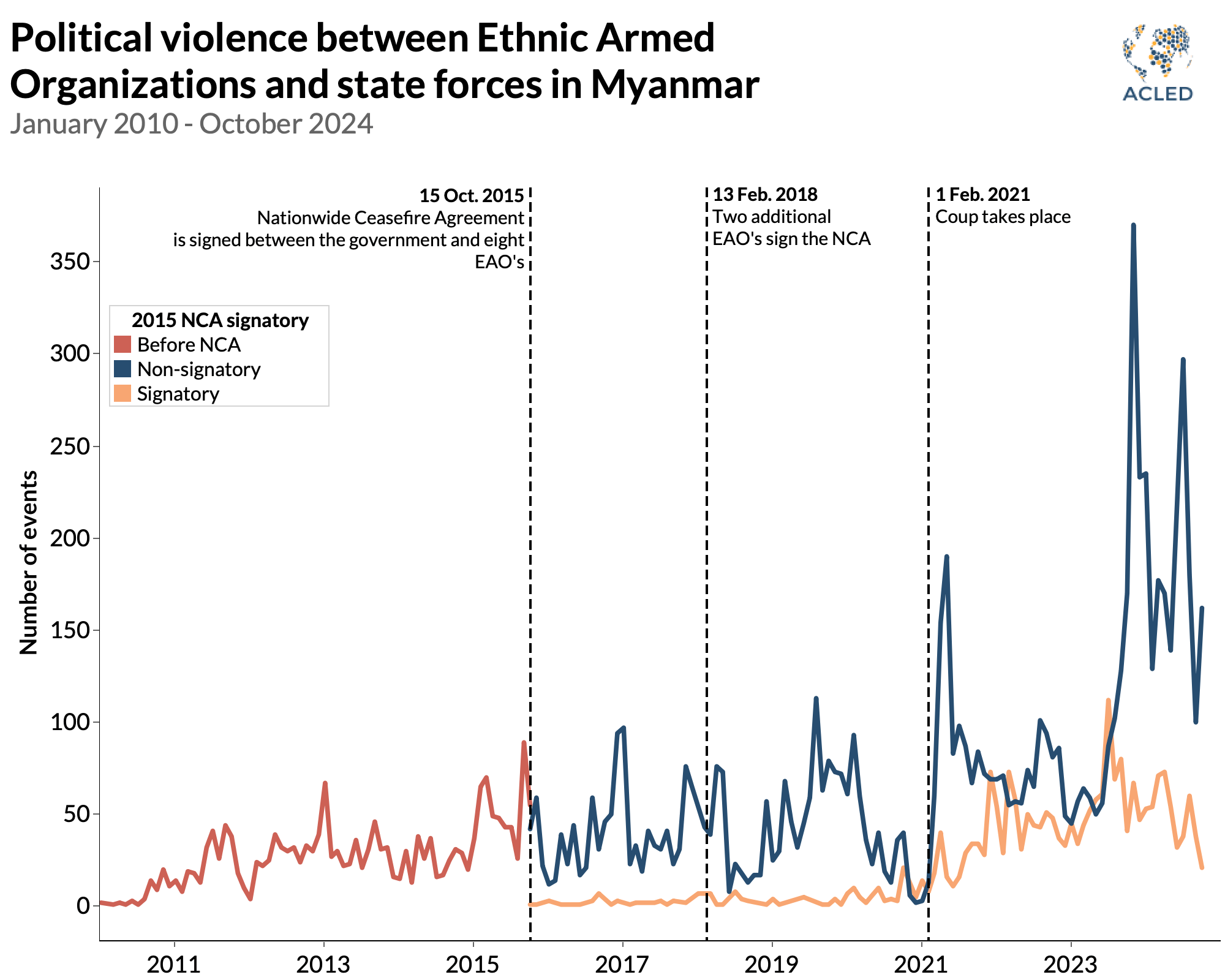

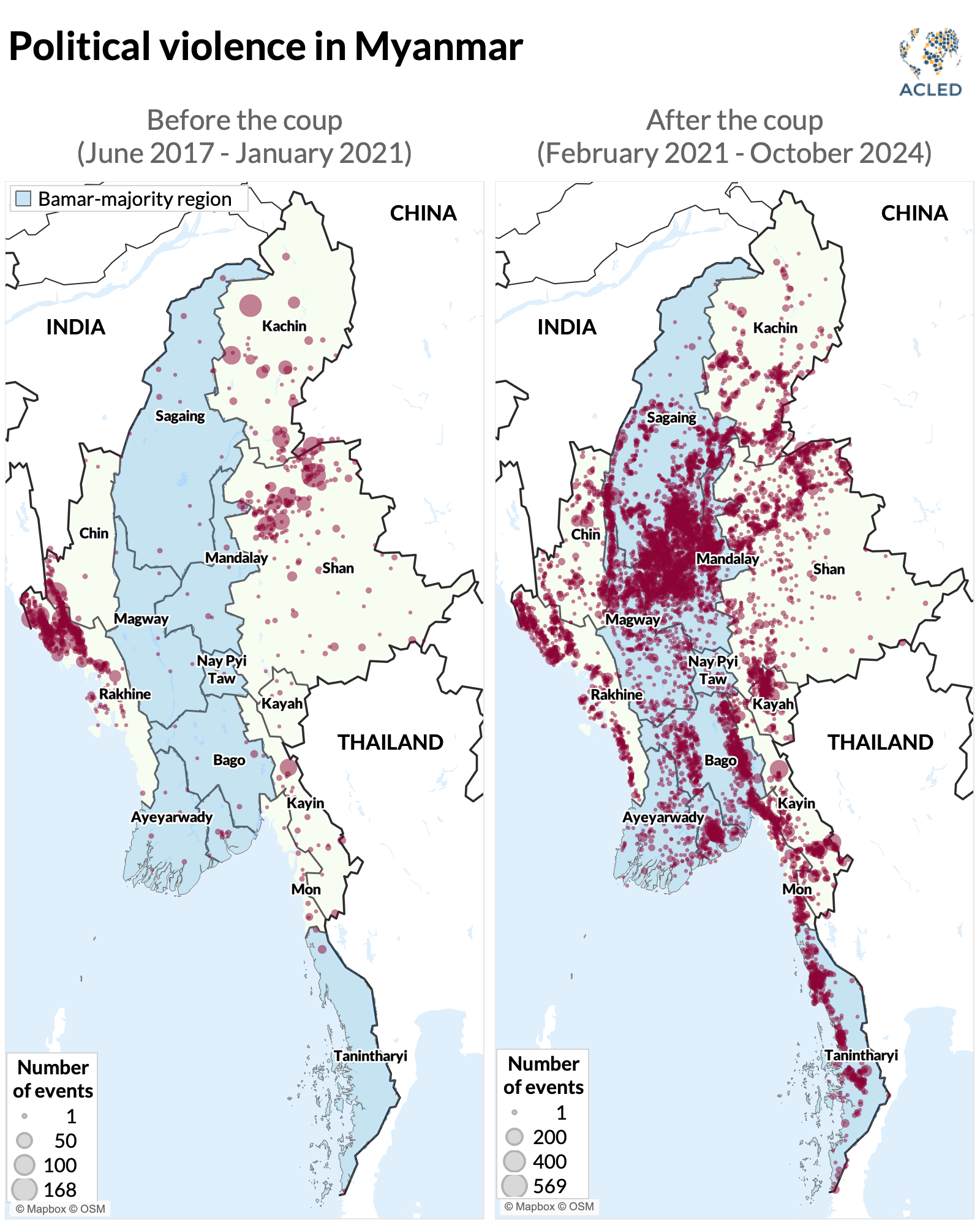

In the years preceding the 2021 coup, the major determinant of EAOs engaging in active conflict with the military was whether they had signed the 2015 Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement (NCA), a wide-ranging, multilateral ceasefire agreement engineered by the Myanmar military and its proxy Union Solidarity and Development Party, which was ruling in the new nominally civilian government. Eight EAOs signed initially, with two more joining as signatories in 2018. Armed conflict largely involved non-NCA signatories fighting against the government, such as the Kachin Independence Organization/Kachin Independence Army (KIO/KIA). ACLED records over 2,600 distinct violent events between 15 October 2015, the day the NCA was signed, and 31 January 2021, ahead of the coup (see graph below). This violence clustered in the ethnic states near land borders with neighboring countries.

In contrast, since the military’s 2021 coup, conflict has spread to at least 321 of Myanmar’s total 330 townships, across all states and regions, including the Bamar-majority regions in central Myanmar that have seen decades of relative peace (see map below). Some of the major NCA signatories, like the Karen National Union/Karen National Liberation Army and Chin National Front/Chin National Army (CNF/CNA), were again fighting the military. The new armed groups that proliferated in response to the military’s torture, rape, and execution of peaceful protesters were founded, or at least supported, by civilians who were provided arms training by EAOs after they fled military violence.

Many of these geographically disparate groups then chose to call themselves People’s Defense Forces (PDFs). They were further bolstered by an announcement in May 2021 by the exiled National Unity Government (NUG) — which was formed by a coalition of parliamentarians and other political leaders ousted by the military’s coup — that local communities had a right to self-defense in the light of the military’s atrocities.3Katherine MOCIT, ‘The State of People’s Defense by the National Unity Government’s Ministry of Defense’, National Unity Government, 28 May 2023 This led to the formalization of many PDFs into battalions under the NUG’s command and control, with other new resistance groups, territorial- or ethnic-based Local Defense Forces (LDFs), preferring to conduct their armed struggle against the military independently.

Given their shared overarching goal of opposing the military, some EAOs aligned with the NUG, drafted the Federal Democracy Charter, and established a common command-and-control structure.4Ye Myo Hein, ‘Greater Military Cooperation is Needed in the Burmese Resistance Movement,’ 18 January 2023 The charter is a political framework document for post-coup governance that guides resistance against the military. Other groups operating outside the NUG framework still informally coordinate with it and other armed groups on individual military operations. This occurs in several different ways: from EAOs providing shelter and training to members of PDFs and LDFs, establishing eight special commando columns;5Allegra Mendelson, ‘Cooperation in Kayin turns a corner,’ Frontier, 12 January 2023 to creating their battalions in their structure for new PDF and LDF members;6Ko Oo, ‘Myanmar’s Spring Revolution Aided by Ethnic Kokang Armed Group,’ The Irrawaddy, 8 March 2023 and launching joint military operations alongside them.7Frontier, ‘“Reclaiming our land”: The resistance marches on Mogok,’ 27 October 2023 Such coordination helps new resistance groups gain field experience, strengthening their capabilities and resources while EAOs are supported by extra troops. Resistance groups in the central areas of Myanmar have now become capable of blocking military reinforcements from reaching and threatening EAO territories.

After decades of armed struggle against the government, EAOs have developed well-established revenue streams and governance and command structures. Their tactics are often directed toward neutralizing hard military targets such as bases and battalions and involve heavy arms and artillery. Territorial expansion and consolidation are guiding objectives, and their strategy involves long-term planning and capturing of population centers. In contrast, newer resistance groups are bound by limited resources and often engage in remote violence using drones, grenades, and IEDs. They use hit-and-run ambushes against soft targets such as military logistics convoys and small security outposts. Their tactics aim to prevent the military from exercising meaningful administration and rule over their areas, a goal shared by the originally non-violent anti-coup movement.

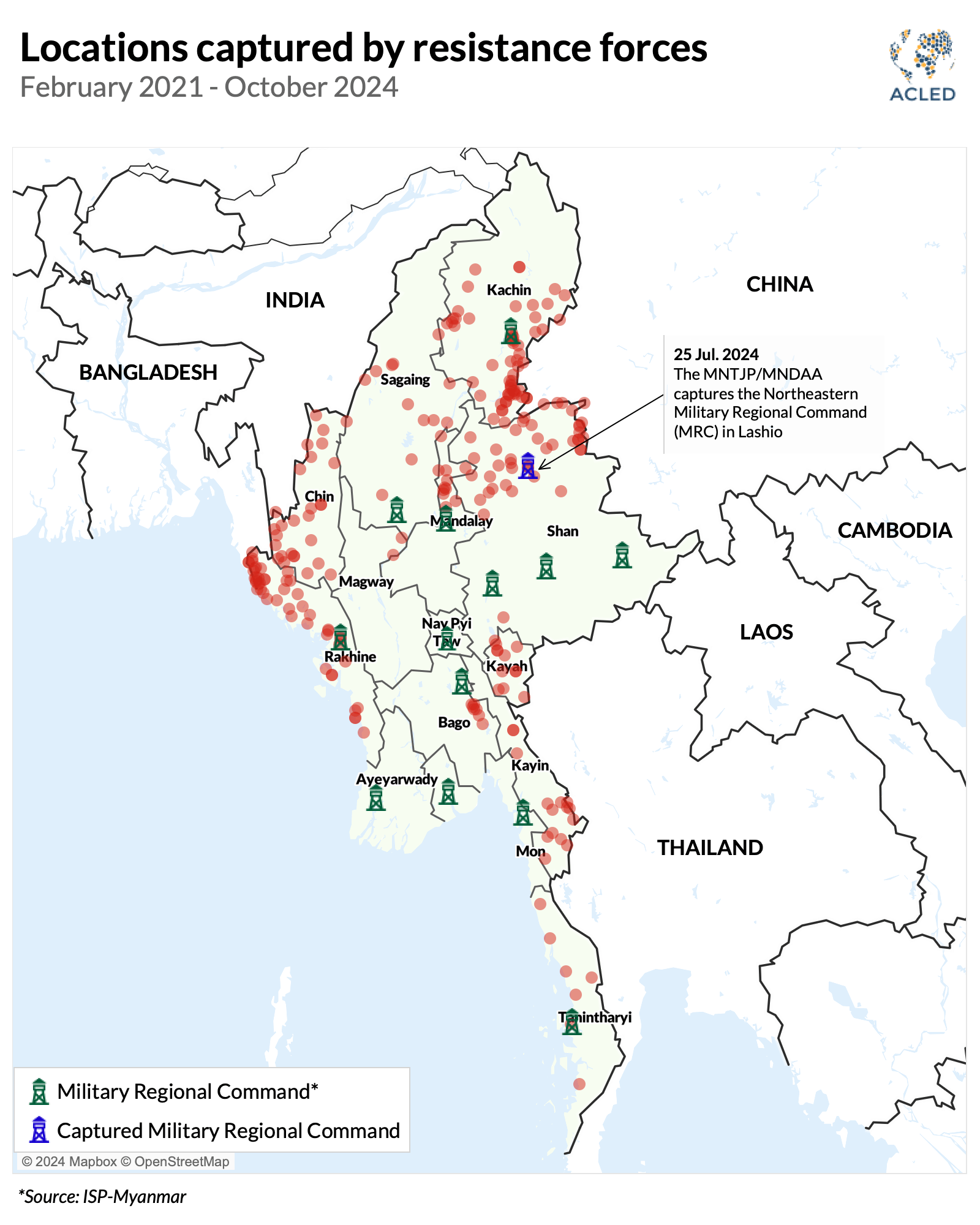

Coordinated operations between EAOs, PDFs, and LDFs have led to many battlefield successes, transforming the conflict environment and putting the military on the back foot. Notably, the Mandalay PDF and others blocked military reinforcements from advancing to northern Shan state on the Mandalay-Lashio Road to engage the Brotherhood Alliance during Operation 1027, leading that alliance to capture 23 towns in northern Shan state since 27 October 2023. From the growth of the new armed resistance groups in 2021 to today, coordination between PDFs, LDFs, and EAOs has led to the capture of at least 80 towns across Myanmar and 200 military bases, and one of the military’s 14 key regional military commands in Lashio of northern Shan state (see map below).

From limited cooperation to competition

While limited coordination has led to military victories for some armed resistance groups, major differences among others have hampered larger cooperation efforts and sporadically triggered infighting. Some EAOs support explicitly denouncing the 2021 coup, while others do not. Some of the new armed resistance groups have integrated directly into the NUG command structure, while others still refuse to. Some resistance groups seek autonomy, while others prefer a federal system.8Myanmar Peace Monitor, ‘Military Successes With Unresolved Federal Puzzles,’ 11 October 2024

The absence of political consensus on a new governance structure has made it impossible to form a unified front against the military regime. This divide stems from disagreements between the NUG and EAOs over future political order and leadership roles. Consequently, cooperation between EAOs and new resistance groups has been limited, often restricted to regional or localized operations aimed at liberating specific territories from military control — even with those groups that keep their distance from the NUG.

Furthermore, despite some PDFs collaborating with EAOs in their operating areas to gain battlefield experience and access to resources, this coordination has not extended into the central Bamar regions for tactical and political reasons.9Saw Lwin, ‘Resistance Armies Poised to Move On to Central Myanmar,’ The Irrawaddy, 31 October 2024 First, the central plains are particularly vulnerable to airstrikes because the area does not have high forest cover, and to ground assaults due to its flat terrain, making it difficult to establish secure bases. Second, EAOs lack intimate knowledge of the local terrain in these regions, further hindering effective coordination. Additionally, there is a significant need for resources to govern newly liberated areas far from EAO bases, which limits the capacity for broader military collaboration. Most importantly, the military coordination between EAOs, PDFs, and LDFs has not been driven by a deeply held shared vision for a future political order. Instead, it is defined only by resistance to the military, and the localized, tactical objectives that are a consequence of that.

The lack of deeper cooperation between armed resistance groups prevents them from more effectively protecting civilians from military abuses. The Myanmar military regularly kills civilians in place of enemy combatants. Most resistance groups are focused on their local areas and use guerilla tactics before disappearing out of reach. They opportunistically assassinate military-appointed administrators and use drones and landmines to attack convoys and checkpoints. For this reason, the military feels continually under threat, and justifies turning whole villages and tracts into enemies. Whenever the military suffers losses, it turns to the closest civilian population center to detain, torture, and kill whoever cannot flee from their advance.10Amnesty International, ‘Myanmar: Military should be investigated for war crimes in response to “Operation 1027”,’ 26 December 2023 Because most of the new resistance groups do not have identifiable territory, and lack the capacity to maintain, let alone meaningfully defend, any new bases. Therefore, the military treats any productive civilian settlement near resistance activity as a resistance base, and soldiers engage in retaliatory attacks. When resistance groups do attack and take over whole towns, or subtly move into settlements to try and administrate them in the military’s absence, the army responds by bombarding them with airstrikes, targeting infrastructure and residential quarters, and displacing residents.

The lack of cooperation between resistance groups adds an additional layer of complexity to the plight civilians and can impede the delivery of humanitarian aid. The unclear chain of command and overlapping territorial claims make it difficult for external organizations to determine who controls specific areas and, by extension, who is responsible for coordinating assistance. The lack of cooperation increases the risk of civilians being detained by the military or resistance groups under the impression of being informants.11Saw Reh, ‘Ethnic Karen armed group linked to killing of civilians in Southern Myanmar,’ Myanmar Now, 23 October 2024 Overlapping security checkpoints and taxation by individual resistance groups, especially along important trade routes, is increasingly burdening the local population and could lead to less public support for the NUG-led resistance.12Naw Theresa, ‘ Anarchy in Anyar: A Messy Revolution in Myanmar’s Central Dry Zone,’ The Diplomat, 10 September 2024

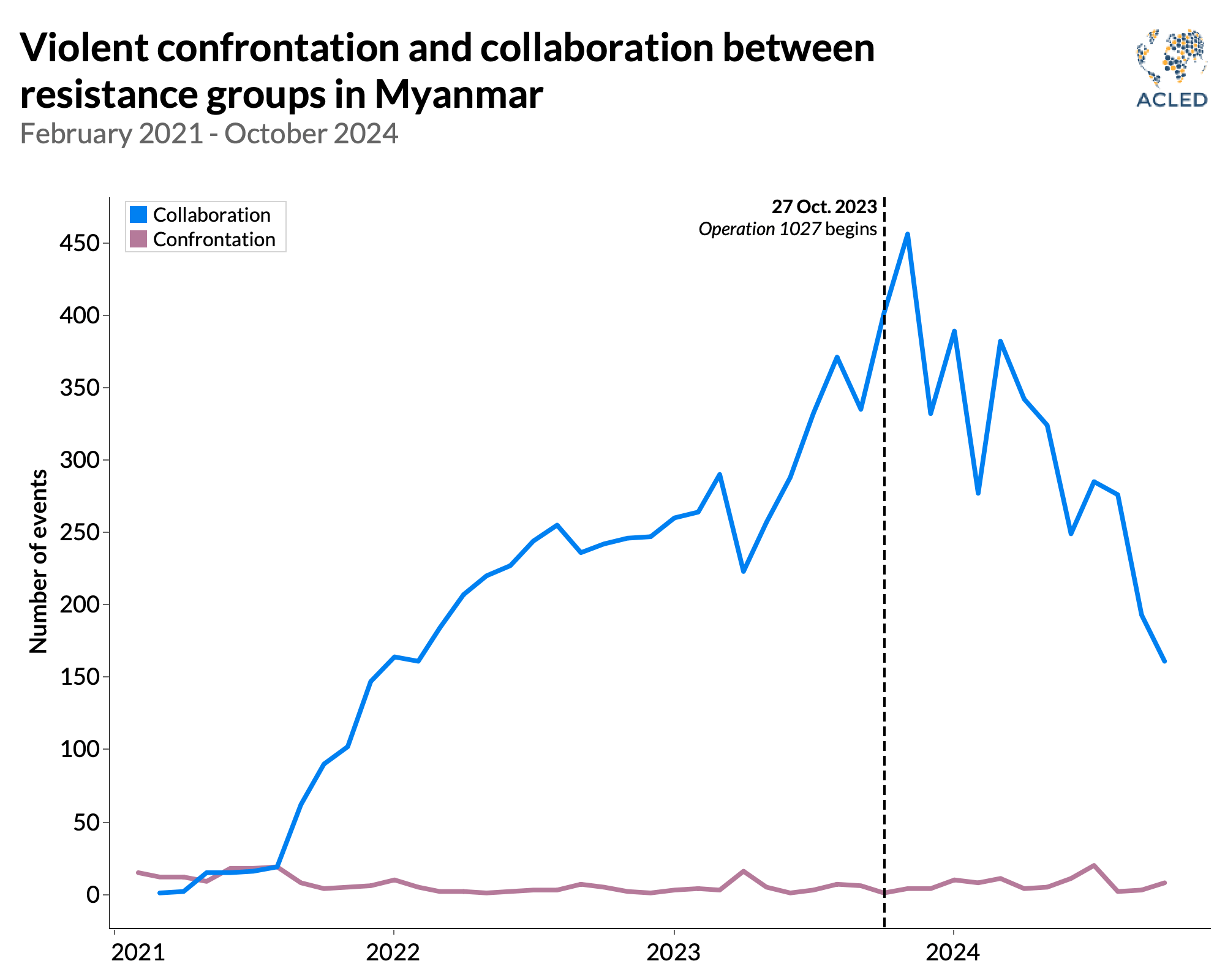

Competition over legitimacy, territory, and resources has not only meant a lack of coordination between groups but even, in its most acute form, led to open conflict between them. Such fighting has seen civilians caught in the crossfire, leading to deaths, injuries, or displacement. ACLED records 306 instances of infighting between resistance groups since the coup. Of these, 77% occurred between EAOs, and 7% occurred between the PDFs and LDFs. While such conflict between groups — accounting for less than 1% of all political violence events since the 2021 coup — consistently pales in comparison to collaborative efforts between groups (see graph below), it nonetheless remains a persistent encumbrance to resistance against the military junta.

Latent tensions between resistance groups: Shan state, Chin state, and Sagaing region

Confrontations between non-miliary-aligned groups have been recorded across nine of Myanmar’s 14 states and regions since the coup. This includes clashes between EAOs that support resisting the 2021 coup and those that do not, as well as between PDFs and LDFs, between PDF battalions, and between EAO-PDF/LDF alliances. The majority of these confrontations are concentrated in Shan state, which accounts for 70% of all such events, driven by competition between established EAOs. Sagaing region follows with 12%, where competition over resources and public support among PDFs and LDFs is widespread. Chin state accounts for the third largest share, with 8%, where competition between alliances — especially LDFs led by well-established EAOs — is particularly intense. The following case studies highlight the unique conflict patterns shaped by inter-group dynamics in Sagaing, Chin, and Shan, and their impacts on resistance to the military.

Shan state

Shan state, situated in eastern Myanmar, is home to a diverse range of ethnic groups, each with distinct political and territorial aspirations. This state has long been a hotspot for armed conflict, with at least a dozen EAOs — both NCA signatories and non-signatories — vying for influence. EAOs across the political divide of non-NCA signatories — united under the umbrella of the Federal Political Negotiation and Consultative Committee (FPNCC) — and NCA signatory EAOs have long engaged in open competition in Shan state. However, tensions have also emerged within the FPNCC amid the rising importance of the Brotherhood Alliance — consisting of the FPNCC-aligned Myanmar National Truth and Justice Party/Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army (MNTJP/MNDAA), Palaung State Liberation Front/Ta’ang National Liberation Army (PSLF/TNLA), and United League of Arakan/Arakan Army (ULA/AA) — on the back of their recent military successes, which has further complicated the conflict landscape.

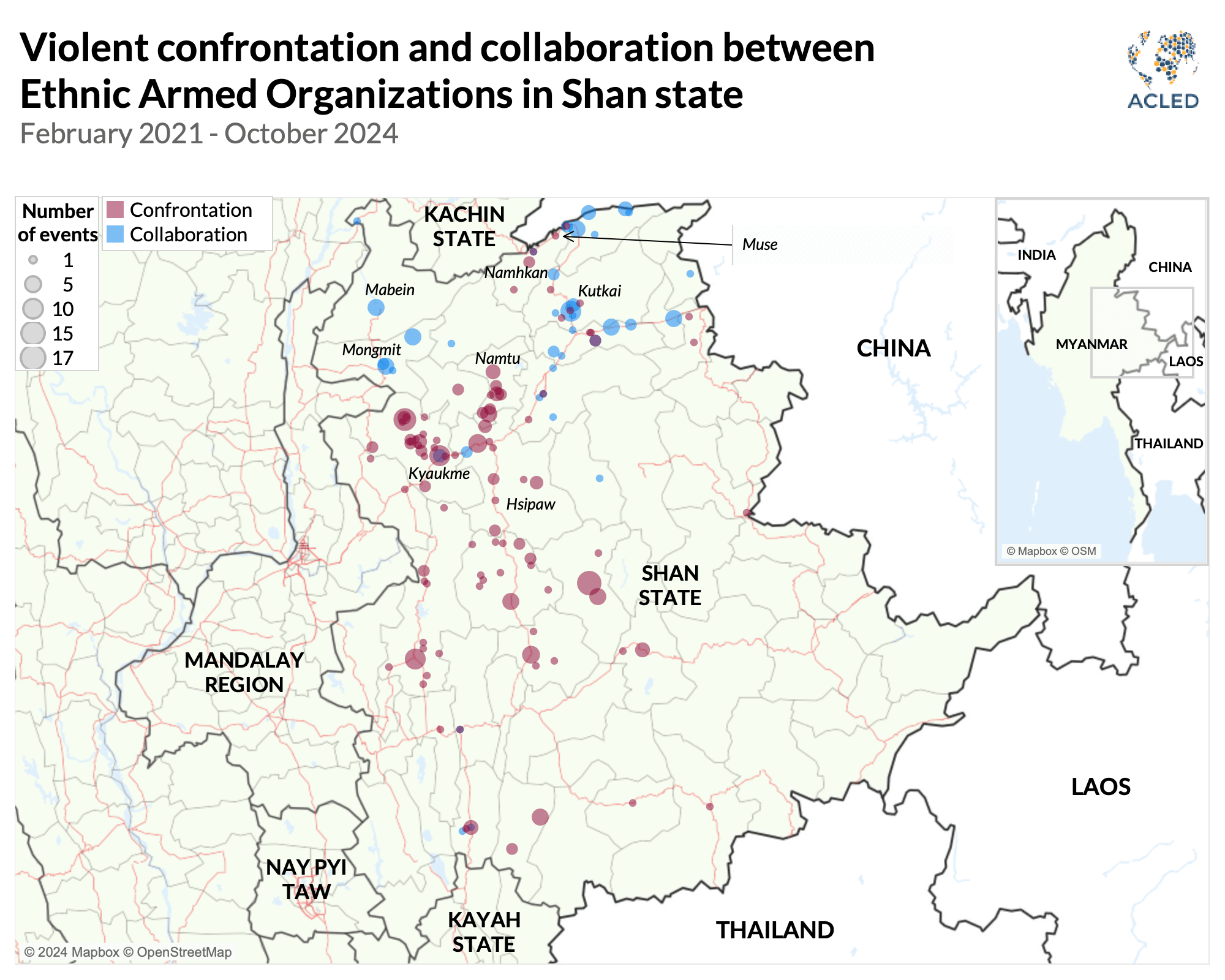

In addition to these EAOs, pro-military ethnic militias and regime forces also operate in the region, further complicating the power dynamics. The tangle of EAOs representing competing interests has positioned Shan state at the center of inter-EAO conflict in Myanmar. Overall, since the coup, ACLED records 236 political violence events across Myanmar where EAOs have been on opposing sides, and 206 of these occurred in Shan state (see map below). At the heart of the conflict in Shan state is a struggle over strategic territory located near the border with China and Thailand, which is critical for political leverage, military positioning, and access to lucrative natural resources, trade routes, and illicit economies. Control over towns, military strongholds, and other key areas is a primary source of conflict, with various EAOs seeking to secure these regions to further their political and military objectives. These territorial disputes are compounded by a changeable political landscape, where fluid alliances between groups are often driven by short-term military or strategic needs.

Recent developments have further intensified the rivalry among some armed groups, including within the FPNCC coalition. Notably, the expansion of territories by the Brotherhood Alliance following the launch of Operation 1027 in October 2023 has brought them into new areas outside their traditional operational zones, exacerbating tensions with other EAOs. When the Brotherhood Alliance-aligned PSLF/TNLA sought to govern newly captured territories in northern Shan state following Operation 1027, it led to tensions with the KIO/KIA, which had long held influence over Kutkai township and some other captured areas. Confrontations between these groups also occurred in Namtu, Mabein, and Mongmit townships.13Reports indicate a confrontation between the PSLF/TNLA and the KIO/KIA in Mabein and Mongmit, but it did not lead to violence. See: Kachin News Group, ‘KIO/KIA and TNLA Vow to Ease Territorial Tensions in Northern Shan State, 25 June 2024 Meanwhile, skirmishes also occurred between the PSLF/TNLA and another FPNCC member, SSPP/SSA-N, in Muse, Namhkan, Hsipaw, and Kyaukme townships, particularly after the second wave of Operation 1027 launched in late May 2024.14Mai Khroue Jar, ‘Tension high between KIA and TNLA in northern Shan state,’ The Irrawaddy, 14 February 2024 The PSLF/TNLA alleged that SSPP/SSA-N purposely disrupted their military operation.15CNI News, ‘TNLA accuses SSPP of disturbing Operation 1027, ‘ 10 July 2024; The Irrawaddy, ‘TNLA’s Political Wing Says Shan Group Disrupting Fight Against Myanmar Junta, ‘ 9 July 2024

Since the launch of Operation 1027 on 27 October 2023, ACLED records 41 violent confrontations between EAOs, compared to 21 in the same period prior. Following public concerns over disputes and tensions among alliance members, these issues were resolved through the FPNCC.16Myanmar Peace Monitor, ‘Frictions in Northern Shan state reach the negotiation table,’ Burma News International Bi-Weekly News Review, Issues 149, 22 July 2024 Leaders from the PSLF/TNLA and KIO/KIA confirmed that there will be no further clashes between them, as they now coordinate and negotiate daily. The PSLF/TNLA stated that the disputes with the SSPP/SSA-N were resolved through FPNCC mediation, with both sides committing to avoid attacks in the future.17Radio Free Asia Burmese, ‘TNLA says the disputes with the SSPP have been resolved, 17 July 2024

The outcomes of these negotiations, coupled with the military airstrikes targeting areas newly controlled by the Brotherhood Alliance, have de-escalated tensions and prevented clashes between FPNCC members. However, confrontations and disputes may still arise over governance of cosmopolitan areas and control of resources, especially if attempts are made to govern these areas without deeper cooperation. Additionally, potential competition between members of the FPNCC and the NCA signatories could exacerbate tensions.

Chin state

Chin, a very small state geographically, is surrounded by mountains and borders India. It is home to several ethnic and linguistic groups that have long-standing differences. In contrast to Shan state, only one established EAO, the CNF/CNA, has opposed the military since 1988. Since the coup, though, the conflict dynamic has been complicated by the formation of 18 LDFs, with two LDFs operating in each township: one representing the town and one representing the local ethnicity.

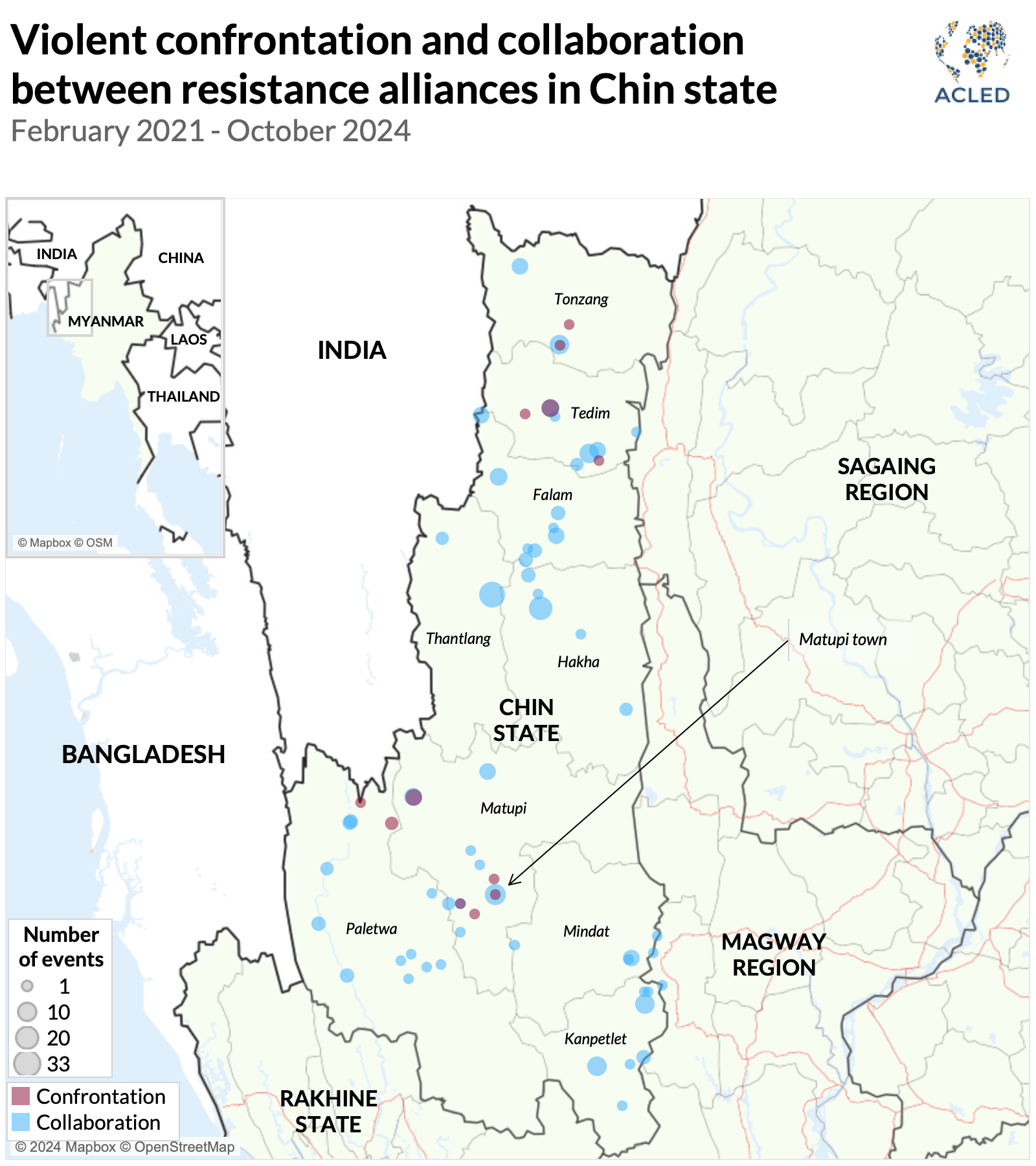

These LDFs, in coordination with the CNF/CNA, were some of the earliest armed groups to resist the military and quickly grew in strength. Some of them operate in border areas with Magway region and have cut off military reinforcements advancing to Chin state from central regions. Many military convoys leaving the lowlands were repeatedly ambushed by Chin LDFs before reaching battlefronts deep in Chin state. Such coordination led them to many successes in Chin state, capturing seven towns until the resistance groups split into two coalitions in December 2023.

Six LDFs formed the Chin Brotherhood, backed by the ULA/AA, another group with significant territory in the south of Chin State, while the rest remained members of the Chinland Council led by the CNF/CNA. The two alliances now disagree on whether and how to found new administrative bodies. Disputes arose over governance, with the Chin Brotherhood, bolstered by the ULA/AA’s support in the south, questioning the CNF/CNA’s dominance.18Michael Martin, ‘Trouble Among the Chin of Myanmar,’ Center for Strategic and International Studies, 1 November 2024 The CNF/CNA alleges that the ULA/AA is meddling in Chin affairs and dividing the Chin ethnic group19Mizzima News from Myanmar, ‘Chinland Government calls on AA to stop interfering in Chin affairs,’ 24 July 2024 and claims the Chin Brotherhood is willing to cede Paletwa township of southern Chin state to the ULA/AA in exchange for support.20Angshuman Choudhury, ‘“Two lions in a cave”: Revolutionary divisions in Chin State,’ Frontier Myanmar, 28 August 2024 While the CNF/CNA controls more territory, the Chin Brotherhood, aided by the ULA/AA, has gained ground in recent months.

The competition between these two alliances has manifested in sporadic armed clashes. In June 2024, fighting escalated over the control of the strategic town of Matupi, a critical waypoint between northern and southern Chin and toward Rakhine. While their fighting did not prevent military successes, it delayed progress and wasted resources, resulting in civilian displacement and casualties on both sides. Both sides tried to resolve the conflict through dialogue with mediators in Delhi city, India but failed to do so.21Burma News International, ‘Meetings to resolve conflict between Chin groups delayed,’ 31 August 2024 Overall, ACLED records 24 cases of resistance allies fighting against one another in Chin state, compared to 242 instances of collaboration against the military — 13 of which were clashes between members of the aforementioned two alliances (see map below).

Since the split, the Chin resistance groups have captured six more towns, with the two alliances each controlling three. While their factions may not significantly affect military operations against the junta, they could hinder the unification of Chinland.

Sagaing region

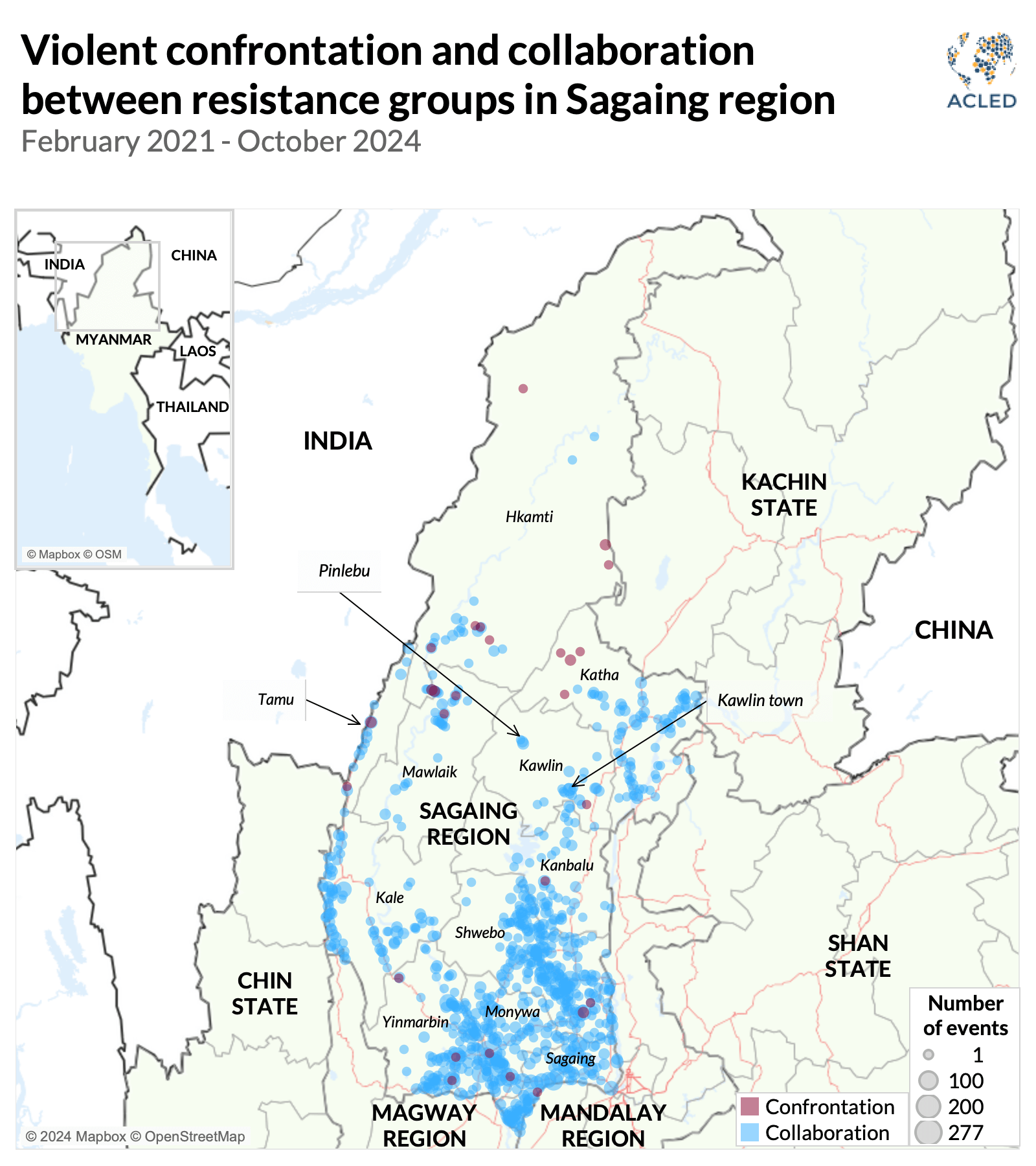

Sagaing region is newly affected by conflict, as it does not historically have well-established EAOs. Thus, since the coup hundreds of diverse resistance groups have operated independently, without unified command structures. These groups tend to have different tactical strategies and varying degrees of success. While the northern part of Sagaing region, which borders Kachin state, follows the collaboration and confrontation patterns seen in Shan state, the southern part has witnessed confrontations between newer resistance groups, such as the PDFs and LDFs. These conflicts are largely driven by groups’ competition over resources and public support.

In northern Sagaing, the PDFs have achieved some military success, largely due to coordination with the KIO/KIAKIA. This alliance between the KIO/KIA and PDFs became the first to liberate a district-level town from the military in November 2023 when it seized Kawlin town, located outside the traditional KIO/KIA operating area. Following this victory, the PDFs advanced further, seizing Pinlebu, a crucial town for transporting supplies to the battlefront and reinforcing defensive positions in the region. Southern Sagaing — historically a major source of recruits for the military — has seen hundreds of PDFs and LDFs operate autonomously to defend against pro-military militias and ground military assaults.

The NUG has established People’s Administration Teams, People’s Security Teams, and People’s Defense Teams (PDTs) as part of a local governance structure aimed at replacing the military administration. The NUG claims they have formed these teams across 250 townships nationwide. While the People’s Administration Teams are civilian organizations, the latter two are armed groups by design. Some LDFs have been converted into PDF battalions or PDTs under the NUG’s direction, but these newer resistance groups — PDFs, LDFs, and PDTs — have yet to coordinate effectively under a unified command structure.

These groups, due to their relatively recent formation, struggle to build a unified command structure and gain the trust needed for effective cooperation. They often compete for resources to fund operations and local support, leading to frequent confrontations. This rivalry has led to retaliatory arrests and shootings. For example, on 24 April 2024, the Burma National Revolutionary Army (BNRA), an LDF group, seized a timber truck from the PDF’s Yinmarbin district battalion in Sagaing region, detaining 30 members. In retaliation, the PDF detained 20 BNRA affiliates the following day. ACLED records 36 confrontations between resistance groups in Sagaing region since 2021, 12 of which involved clashes between PDFs and LDFs (see map below).

The results in terms of territorial control and overall resistance success have been more limited in central Myanmar compared to areas with stronger coordination, such as Shan state. Forming effective collaborations in this region is particularly challenging: Nearly 1,700 armed groups have been involved in political violence since the coup, compared to fewer than 130 groups in Shan state, according to ACLED data. The lack of unity, geographical disadvantages, and central leadership in Sagaing have hindered the ability of resistance groups to achieve significant territorial control or effectively challenge the military’s presence.

Regardless of their differences, such a large number of discrete resistance groups fighting the military simultaneously across multiple fronts, independently and at different speeds, can also be seen as an organic strategy to help all groups maximize their chances of achieving their goals. For the NUG’s part, it has expressed the sentiment that “all roads [lead] to Nay Pyi Taw,” implying that any military defeat, no matter how small or marginal, assists in the overall effort to encircle and attack the military’s headquarters.22Myanmar Now, ‘Junta moves to “fortify Naypyitaw at all costs”,’ 20 November 2023; Security Risks Monitor, ‘All Roads to Naypyidaw says resistance defence minister,’ 21 November 2023 While competition, by definition, weakens the resistance movement against the military, there have not yet been major clashes that have affected battle readiness against the military forces. Moreover, EAOs, PDFs, and LDFs that are currently fighting the military always prioritize that fight above their differences.

Prospects of coordination and competition

The vast and diffuse armed resistance to the military’s 2021 attempted coup makes the Myanmar military look weak and suggests it could be defeated if revolutionary groups were ever to unify more concretely. Groups’ differing political visions for the future of Myanmar and local objectives still prevent this unity, imperiling resistance groups’ momentum and exposing civilians to conflict. Competition for control over strategic territories, lack of cooperation among EAOs and other resistance factions, and ongoing infighting have not only hindered efforts to challenge the military junta but have also failed to prevent the suffering of the people they seek to defend.

In this environment, the military will likely continue its ceasefire politics and divide-and-rule tactics to deepen the rifts among armed resistance groups. It will also likely negotiate with EAOs to defeat newer, younger anti-coup armed groups. The Myanmar army has rarely negotiated in good faith with EAOs and has instead perpetuated war on multiple fronts since 1949.23Kevin Wood, ‘Ceasefire capitalism: military-private partnerships, resource concessions and military-state building in the Burma-China borderlands,’ The Journal of Peasant Studies, 2011, pp.747-770 When the Myanmar military has negotiated with EAOs in the past, it has done so to reach bilateral ceasefires and peace agreements that it has used to divide and conquer temporarily. These agreements have facilitated new economic opportunities, usually related to tax, trade, and resource exploitation, which have caused friction and fractures within EAOs and border communities. In some instances, this has led to the formation of new conflict actors such as Border Guard Forces, which integrated into the military’s command structure, and ethnic militias with members recruited from the local population but supervised by the military.24David Brenner, ‘Ashes of co-optation: from armed group fragmentation to the rebuilding of popular insurgency in Myanmar,’ Conflict, Security & Development, 3 August 2015; John Buchanan, ‘Militias in Myanmar,’ The Asia Foundation, July 2016

On 26 September 2024, the military invited PDFs to disarm and enter its planned 2025 elections as political parties.25Democratic Voice of Burma, ‘Military regime calls on resistance groups to abandon violence and take “political path” in planned elections,’ 27 September 2024 The military later claimed it would not compromise with armed resistance groups unless they tried to solve political problems at the negotiation table.26The Irrawaddy, ‘Junta Boss Repeats Vow to Crush Armed Opposition,’ 16 October 2024 Anti-coup resistance groups allied with the NUG or under the command of the NUG called the military invitation an attempt at manipulation.27Nyein Chan Aye, ‘Myanmar military urges armed groups to stop fighting, join elections,’ Voice of America, 27 September 2024

Without negotiation breakthroughs overcoming political differences between resistance groups, disputes over resources, territory, and ideology will likely continue. EAOs are taking new territory and expanding military operations beyond their previous areas of control. This can lead to communal violence in contested areas where multiple ethnic groups reside. For example, the ULA/AA’s control over Paletwa township in Chin state, which borders India and Bangladesh, has led to backlash and heightened ethnic tensions among the predominantly Chin population. While disputes have been temporarily set aside to confront a shared adversary, they remain unresolved.28Frontier Myanmar, ‘“We have a common enemy”: Paletwa dispute on hold but unresolved,’ 9 June 2023

On the other hand, there are emerging opportunities for groups to cooperate on new operations against the military. Fighting along with EAOs, some of the NUG-PDF battalions and local defense forces have evolved into institutionalized armies with command and control, weapons, and technology. For instance, the Mandalay PDF has taken control of key towns near Mandalay, the previous royal capital and second-largest city in the country. With the support of key EAOs, taking Mandalay would be a huge victory and would allow the resistance to threaten the military in Nayipyitaw directly.29Nayt Thit, ‘As Resistance Enters Mandalay, is Myanmar’s Second City on Brink of Falling?,’ The Irrawaddy, 3 September 2024; Morgan Michaels, ‘Is the Brotherhood headed to Mandalay?’ International Institute for Strategic Studies, October 2024 Controlling Mandalay would provide opportunities for new alliances between resistance groups to integrate and consolidate the gains made over the past years. While such an eventuality was impossible to consider three years ago, the regime’s recent failed attempt at an accurate nationwide census has again exposed the continued widespread resistance to the 2021 coup and highlighted the consolidation of gains made by resistance groups. The military’s efforts were limited to the few urban wards under reliable military control, and, even there, soldiers shadowed the enumerators and demanded bribes from residents being counted.30Frontier Myanmar, ‘Losing count: Chaotic census kicks off,’ 11 October 2024 In this context, the maturing armed actors encroaching on Mandalay may not need to take the city by brute force but could rely on the public’s support.

| EAOs | Ethnic Armed Organizations |

| KIO/KIA | Kachin Independence Organization/Kachin Independence Army |

| RCSS/SSA-S | Restoration Council of Shan State/Shan State Army-South |

| SSPP/SSA-N | Shan State Progress Party/Shan State Army-North |

| NCA | Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement |

| CNF/CNA | Chin National Front/Chin National Army |

| PDFs | People’s Defense Forces |

| NUG | National Unity Government |

| LDFs | Local Defense Forces |

| FPNCC | Federal Political Negotiation and Consultative Committee |

| MNTJP/MNDAA | Myanmar National Truth and Justice Party/Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army |

| PSLF/TNLA | Palaung State Liberation Front/Ta’ang National Liberation Army |

| ULA/AA | United League of Arakan/Arakan Army |

| PDTs | People’s Defense Teams |