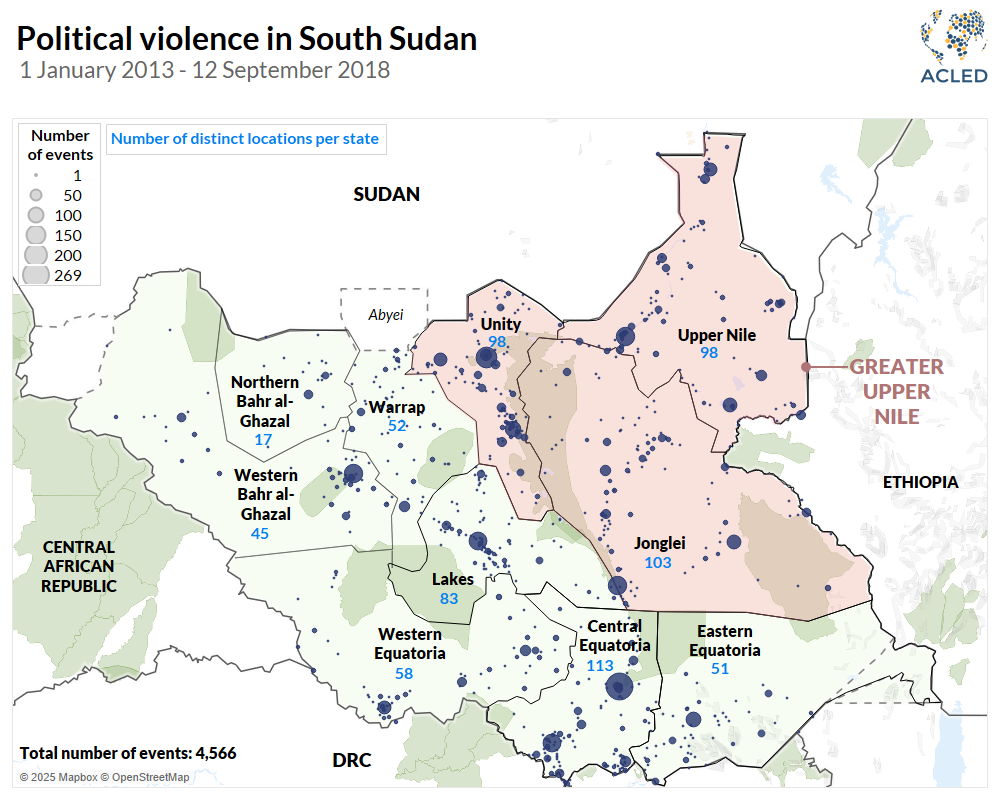

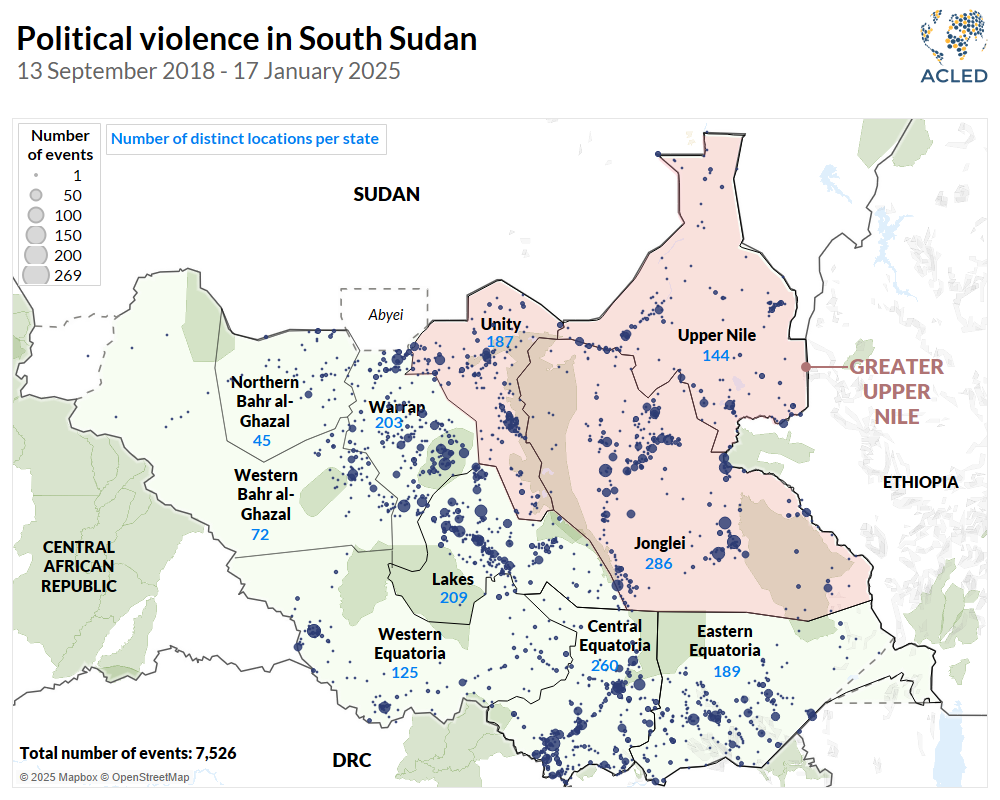

In September 2024, South Sudan’s government postponed elections until 2026.1United Nations, ‘South Sudan: Postponing long-awaited elections “a regrettable development,”’ 7 November 2024 This and other violations of the 2018 Revitalized Agreement on the Resolution of the Conflict in South Sudan (R-ARCSS) reinforce the country’s deep divisions and continued, widespread violence.2James Barnett, ‘War and Peace in South Sudan,’ New Lines Magazine, 5 February 2024 After a devastating civil war (2013-2018), politicians, generals, and communities have lacked a unifying identity or incentive and have focused on shoring up their political power, undermining their rivals, and diversifying their economic holdings. As South Sudan’s oil fields dry up, wealth and sustenance are carved out wherever they can be found, often violently.3Joshua Craze, ‘Payday Loans and Backroom Empires: South Sudan’s Political Economy since 2018,’ Small Arms Survey, October 2023 The central government in Juba deprives national institutions of funding, neither state nor rebel forces are committed to integrating into a unified military, and state officials at all levels exploit their positions to fund expensive lifestyles and large patronage networks.4UN Security Council, ‘Final report of the Panel of Experts on South Sudan submitted pursuant to resolution 2633 (2022),’ S/2023/294, 26 April 2023; Simona Foltyn, ‘How South Sudan’s elite looted its foreign reserves,’ The Mail & Guardian, 3 November 2017 Politicians have long plundered South Sudan’s main source of wealth, its state-owned oil company, Nilepet, to fuel their wars and wealth, and the country remains economically destitute.5Global Witness, ‘Capture on the Nile,’ April 2018 Across South Sudan, violence has become more geographically dispersed as armed groups have fractured. Between 1 January 2013 and the signing of R-ARCSS on 12 September 2018, there were conflict events in 718 distinct locations, compared to 1,720 between 13 September 2018 and 17 January 2025 (see maps below). Given these realities, the peace process could hardly address South Sudan’s myriad, local-level contests over borders, resources, and political positions.6Joshua Craze and Ferenc David Marko, ‘Death by Peace: How South Sudan’s Peace Agreement Ate the Grassroots,’ African Arguments, 6 January 2022

Greater Upper Nile region, which consists of Unity, Upper Nile, and Jonglei states, exemplifies South Sudan’s diffuse, opportunistic violence and accounts for 43% of communal militia activity since 2018. In 2024, it accounted for 49%. After decades of existential war in Greater Upper Nile, communities and leaders are mobilizing whatever forces they can to make sure they do not lose political power and wealth once the elections and peace process are formally concluded. This political-economic contest undergirds violence across several states, including deadly raids on communities and cattle involving the Bor Dinka, Lou Nuer, and Murle ethnic groups in Jonglei state; state repression between Nuer factions in Unity state; demographic engineering by the Padang Dinka against the Nuer and Shilluk in Upper Nile state; and the battle between the largely Shilluk Agwelek and Nuer Kitgwang splinter factions across all three states.

The civil war’s legacy

In 2013, South Sudan’s President Salva Kiir Mayardit and Vice President Riek Machar Teny Dhurgon plunged South Sudan into civil war as they fought for control of the newly formed state, which attained independence in 2011, and its wealth. As the head of the ruling Sudan People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM), Kiir mobilized a network of ethnic Dinka largely from Northern Bahr al-Ghazal state, while Machar mobilized ethnic Nuer communities largely from Greater Upper Nile under the banner of the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement-In Opposition (SPLM-IO).

As Machar is from Unity state and Unity and Upper Nile states contained South Sudan’s lucrative oil fields, Greater Upper Nile became an important battleground and base during the civil war.7Alex de Waal, ‘When kleptocracy becomes insolvent: Brute causes of the civil war in South Sudan,’ African Affairs, July 2014; The Sentry, ‘Fueling Atrocities: Oil and War in South Sudan,’ March 2018 Both factions forged alliances, enticed defectors, and collectively punished communities, leaving South Sudan fractured, militarized, and traumatized. Though SPLM and SPLM-IO signed the R-ARCSS peace deal in 2018, in reality, Kiir was largely victorious over Machar and faced little incentive to share power or build a representative democracy.8Alex de Waal, et al., ‘South Sudan: The Politics of Delay,’ The London School of Economics and Political Science Conflict Research Programme, 3 December 2019 Indeed, it took another two years after signing the peace deal for Kiir and Machar to accede to a unity government, all while Kiir suppressed dissent, arrested political rivals, and secured a vast economic empire for himself and his family.9UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, ‘South Sudan: UN Inquiry’s report finds that entrenched repression imperils prospects for peace, human rights and credible elections,’ 5 October 2023; Garang Malak, ‘Salva Kiir breaks silence on Juba shootout that put spotlight on security agencies’ excesses,’ The East African, 29 November 2024; The Sentry, ‘Kiirdom: The Sprawling Corporate Kingdom of South Sudan’s First Family,’ 19 November 2024 In this context, there has been neither resolution nor reparation for the extensive displacement, atrocity crimes, and political hostility of an essentially unresolved civil war.

Conflict dynamics in Greater Upper Nile

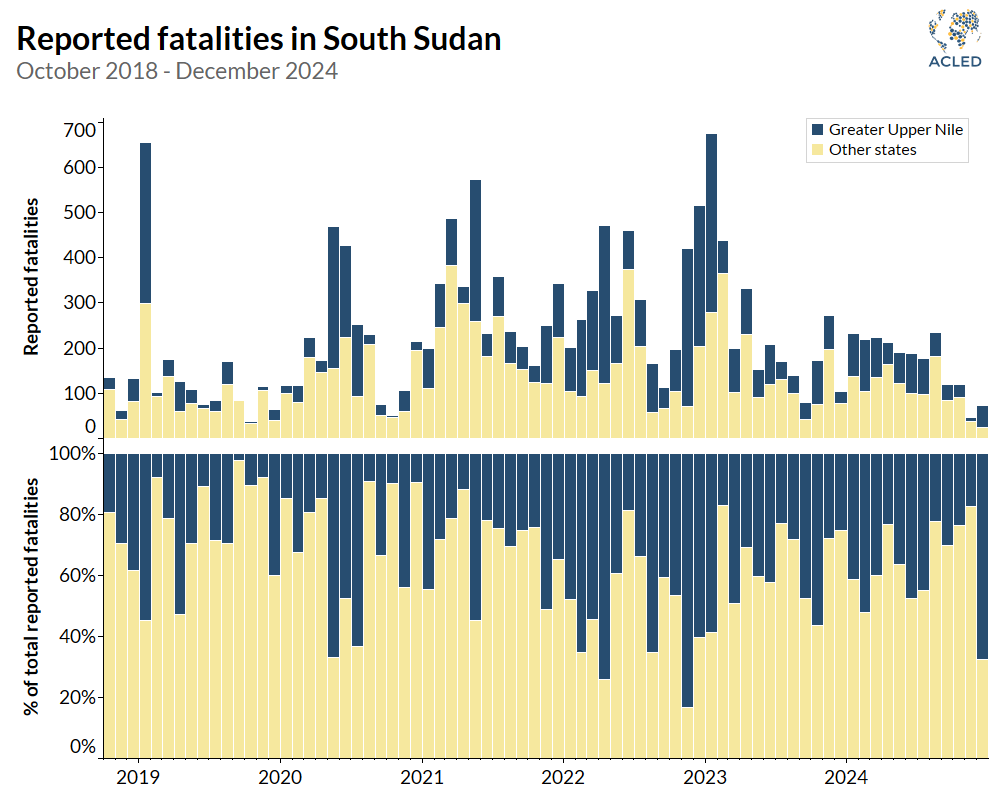

Since 2018, tens of thousands of South Sudanese civilians have been killed, injured, or abducted by political factions, communal militias, or criminal gangs (labels that are often used interchangeably to describe many of these groups). Unity, Upper Nile, and Jonglei states have been particular hotspots for violence both during and after the civil war. While the three states contain approximately 24% of South Sudan’s population,10UNOCHA, ‘South Sudan – Subnational Population Statistics,’ 2020 they account for 40% of all reported fatalities from political violence — over 6,700 out of nearly 17,000 combatant and civilian deaths — as recorded by ACLED between October 2018 and December 2024, with an average of 87 monthly fatalities (see graph below).

Violence in the expansive Greater Upper Nile involves myriad actors and motivations. Because the White Nile river snakes through the region, Greater Upper Nile’s flood plains and waterways provide for bountiful agriculture, fishing, pastoralism, and trade and transport.11Republic of South Sudan Ministry of Environment, ‘Fifth National Report to the Convention on Biological Diversity,’ December 2015 Historically, rituals and agreements regulated the intensity and longevity of conflicts between and within clan groups over land ownership, pastoral routes, and compensation for violence and theft.12Hannah Wild, Jok Madut Jok, and Ronak Patel, ‘The militarization of cattle raiding in South Sudan: how a traditional practice became a tool for political violence,’ Journal of International Humanitarian Action, 2 March 2018; Ali Jammaa Abdalla, ‘People to people diplomacy in a pastoral system: A case from Sudan and South Sudan,’ Pastoralism: Research, Policy and Practice, 29 April 2013 However, half a century of making war and attempting to forge peace in South Sudan has fractured Greater Upper Nile’s communities and their livelihoods. While the rivalry between Kiir and Machar is often framed as the key driver of South Sudan’s violence in both the 1990s and 2010s, it is merely a national-level manifestation of a nuanced process of mobilization and enrichment along ethnic lines. Political rivals, traditional leaders, and businesspeople weaponize identities through hate speech and patronage networks, mobilizing or partnering with armed youth, government soldiers, and mercenaries.13Diana Felix da Costa, Naomi Pendle, and Jérôme Tubiana, ‘What is happening now is not raiding, it’s war,’ Routledge Handbook of the Horn of Africa, 2022; Flora McCrone and The Bridge Network, ‘The War(s) in South Sudan: Local Dimensions of Conflict, Governance, and the Political Marketplace,’ The London School of Economics and Political Science Conflict Research Programme, February 2021; UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, ‘South Sudan: Dangerous rise in ethnic hate speech must be reined in – Zeid,’ 25 October 2016 These networks have pursued the connected goals of political power and financial gain by fighting over land, oil wells, cattle herds, and political offices.14UNOHCHR, ‘South Sudanese political elites illicitly diverting millions of US dollars, undermining core human rights and stability – UN experts note,’ 23 September 2021; Andy Catley, ‘Livestock and Livelihoods in South Sudan,’ Institute of Development Studies, 5 December 2018; Audrey Foo, ‘Land Acquisition in Sudan and South Sudan: Emptying the Bread Basket,’ Advocates for International Development, 2 September 2019; Global Witness, ‘Capture on the Nile,’ April 2018

South Sudan’s predominant pastoral livelihoods have become a big business involving violent raiding and vast inequality, while militias and foreign corporations continually exploit its forests and minerals.15Stefan Bakumenko, ‘Predatory economics fuelling insecurity: violence and the commodification of labour in South Sudan,’ Review of African Political Economy, 21 April 2023 ; Denis Morris Mimbugbe, ‘‘Loggers of Impunity” Leaving South Sudan’s Forest in Ruin,’ Rainforest Journalism Fund, 22 October 2022 ; The Sentry, ‘Untapped and Unprepared: Dirty Deals Threaten South Sudan’s Mining Sector,’ April 2020 Political offices are treated as personal coffers, resulting in massive, unaccounted-for state deficits and the systematic looting of development aid.16Amnesty International, ‘Reprioritising Resources for the Future of South Sudan,’ 29 August 2024 Added to this, proxy warfare and widespread recruitment along ethnic lines during the First (1955-1972) and Second (1983-2005) Sudanese civil wars left South Sudan awash with weapons and reasons to use them, including cycles of raiding, blood feuds, and political contestation.17Jok Madut Jok and Sharon Elaine Hutchinson, ‘Sudan’s Prolonged Second Civil War and the Militarization of Nuer and Dinka Ethnic Identities,’ African Studies Review, September 1999; Saferworld, ‘Challenges to small arms and light weapons control in South Sudan,’ November 2022 As a result of these dynamics, the basic resolution of grievances or acquisition of resources has become an exercise in violence.18Majak D’Agoôt, ‘Understanding the Colossus: The Dominant Gun Class and State Formation in South Sudan,’ Journal of Political & Military Sociology, 2020

Factions fight for wealth and power (2022-2024)

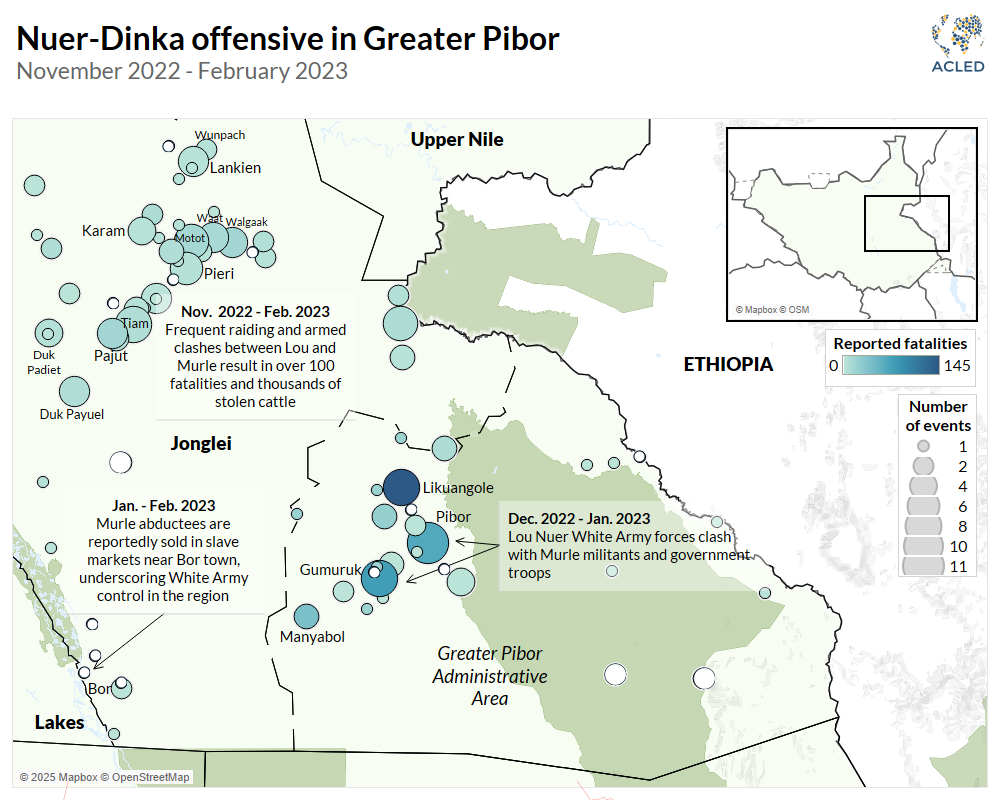

With historically and culturally fluid boundaries, Greater Upper Nile’s three states face similar yet discernible political, economic, and environmental pressures. In Jonglei state, ethnic Murle, Lou Nuer, and Bor Dinka have fought for years over cattle, slaves, and loot.19Diana Felix da Costa, Naomi Pendle, and Jérôme Tubiana, ‘What is happening now is not raiding, it’s war,’ Routledge Handbook of the Horn of Africa, 2022; International Crisis Group, ‘South Sudan: Jonglei – “We Have Always Been at War,”’ 22 December 2014; Tom Richardson, ‘Pastoral Violence in Jonglei,’ Mandala Projects, December 2011; Climate Diplomacy, ‘Conflict between Lou Nuer and Murle in South Sudan,’ accessed on 9 December 2024 In 2022 and 2023, Bor Dinka and Lou Nuer militias undertook a joint offensive in Murle lands in the Greater Pibor Administrative Area (GPAA).20Reliefweb, ‘IRNA Report: To Conflict Affected People in Gumuruk County, Greater Pibor Administrative Area (GPAA),’ 18 January 2023; Joshua Craze, ‘A Pause Not a Peace: Conflict in Jonglei and the GPAA,’ Small Arms Survey, May 2023 Between November 2022 and February 2023, ACLED records at least 694 reported fatalities in Jonglei, including 488 in GPAA alone. In late December 2022 and early January 2023, Lou Nuer White Army forces clashed with Murle militias and depleted government forces (that soon retreated) in and around Gumuruk and Pibor towns.21UNOCHA, ‘South Sudan: Humanitarian Snapshot (December 2022),’ December 2022; Radio Tamazuj, ‘Several feared dead as Jonglei youth overrun Gumuruk,’ 28 December 2022 According to ACLED data, these battles in the GPPA accounted for over half of the offensive’s reported fatalities (see map below). Hundreds more were injured, there were multiple reported cases of sexual violence, and at least 300 people were abducted. White Army forces then transported their loot and Murle abductees to slave markets in Jonglei’s Bor town.22Joshua Craze, ‘A Pause Not a Peace: Conflict in Jonglei and the GPAA,’ Small Arms Survey, May 2023 Having raided their enemy’s capital despite government resistance, it became clear that the White Army, not the national or state government, was ascendant in South Sudan’s largest state.

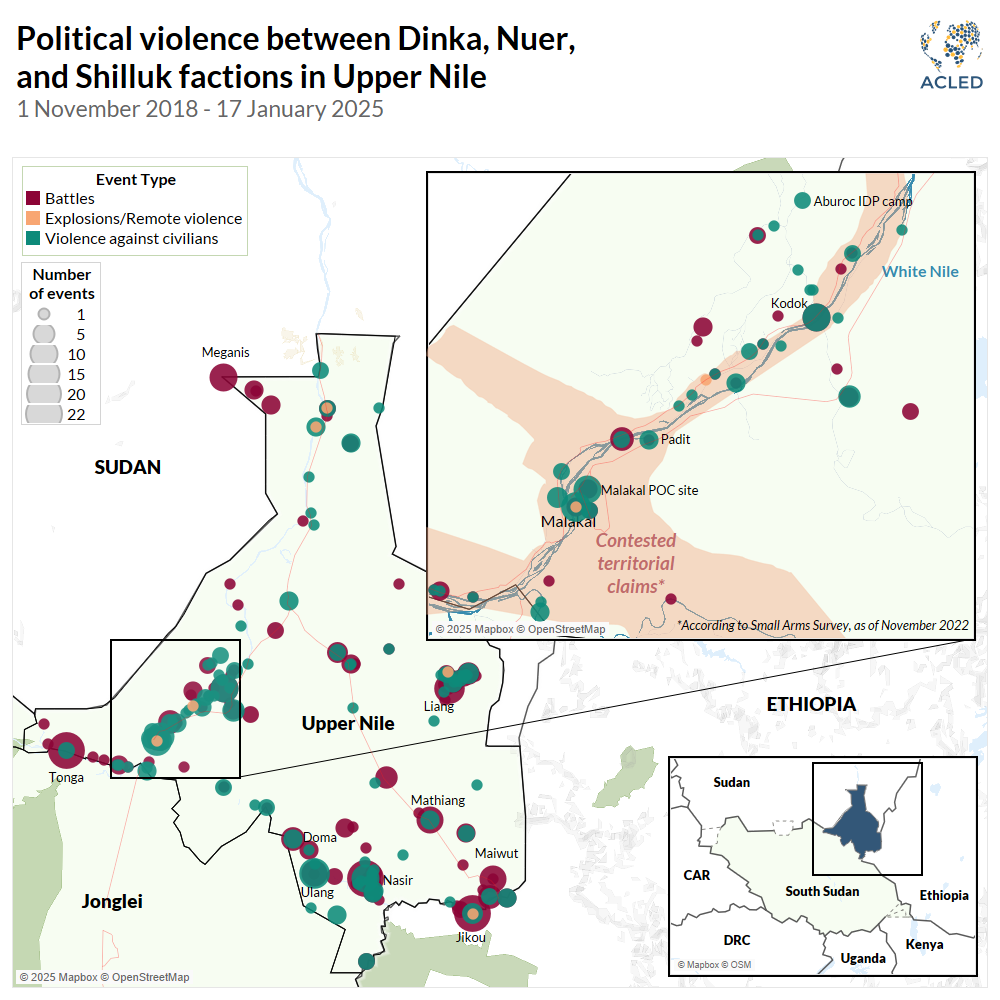

In neighboring Upper Nile state, the Padang Dinka-dominated state government, supported by the national government, official forces, and communal militias, is engaged in complex demographic engineering and land-grabbing against ethnic Shilluk and Nuer along the banks of the White Nile. This political-economic campaign frequently involves attacks by Dinka militias or government forces against civilians living, traveling, or working along the White Nile river (see map below).23Joshua Craze, ‘The Periphery Cannot Hold: Upper Nile since the Signing of the R-ARCSS,’ Small Arms Survey, November 2022 This engineering further manifests as a concerted campaign of settling Dinka families in Shilluk homes in Malakal town while Shilluk and Nuer communities who were displaced during the civil war remain stranded in the neighboring Malakal Protection of Civilians (POC) site, which is administered by the United Nations Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS).24Flora McCrone and The Bridge Network, ‘The War(s) in South Sudan: Local Dimensions of Conflict, Governance, and the Political Marketplace,’ The London School of Economics and Political Science, February 2021; Vivian Caragounis and IridaCon, ‘Voices on the Conflict in Malakal,’ Pax for Peace, 31 January 2022; International Crisis Group, ‘South Sudan’s Splintered Opposition: Preventing More Conflict,’ 25 February 2022 The Nuer and Shilluk internally displaced people (IDPs) face deprivation and contestation in the crowded, under-resourced displacement camp. In June 2023, a dispute over a water well quickly spiraled, resulting in a stabbing.25UNOCHA, ‘Situation Report: Malakal Conflict Induced Displacement due to violent clashes in Malakal PoC (As of 4th July 2023),’ 4 July 2023; United Nations Mission in South Sudan, ‘UNMISS Appeals for Calm After Deadly Clashes in Malakal Protection of Civilians Site,’ 29 May 2023 On 8 June, displaced Nuer and Shilluk clashed with small arms inside the camp. Twenty people were reportedly killed and dozens more were injured.26REACH Initiative, ‘Emergency Situation Overview: Sudan-South Sudan Cross Border Displacement,’ June 2023 The camp’s Nuer then burned their shelters and marched out of the camp in protest, seeking shelter elsewhere. In some cases, they took up arms and mobilized into Nuer militias like the White Army.27UNMISS, ‘UNMISS Urges Malakal PoC Community Leaders to Address Root Causes of Violence,’ 11 June 2023As Nuer White Army youth operate across Greater Upper Nile, the Dinka government works to dominate fertile lands along the White Nile river, and displaced Shilluk seek to return to their burned or expropriated homes, this existential conflict over land and belonging shows no signs of dissipating.

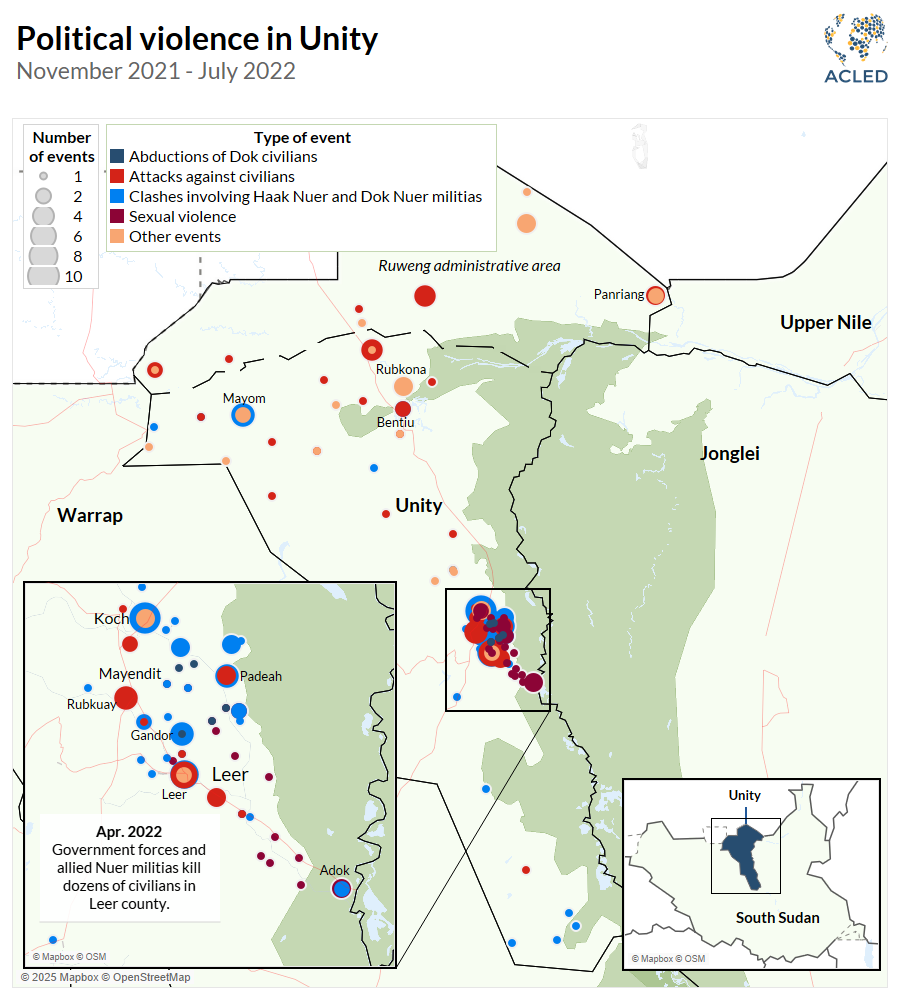

In Unity state, Machar’s Nuer homeland, SPLM-IO is weakened and beset by an overbearing, frequently violent state government.28Joshua Craze, ‘The Body Count: Controlling Populations in Unity State,’ Small Arms Survey, August 2023 In late 2021, clashes that broke out between Haak Nuer and Dok Nuer militias in Leer county escalated into an April 2022 offensive marked by widespread sexual violence carried out by government forces and allied Haak and Jagei Nuer militias against Dok civilians in April.29UNMISS, OHCHR, ‘Attacks against civilians in southern Unity State, South Sudan, February – May 2022,’ September 2022; Ceasefire & Transitional Security Arrangements Monitoring & Verification Mechanism, ‘Final Report on the Armed Clashes and Violations Against Civilians in Koch and Leer Counties in Unity State,’ 26 July 2022; Médecins Sans Frontières, ‘Renewed violence in Leer leads to dozens killed, including MSF staff member,’ 26 April 2022; REACH Initiative, ‘Leer County Rapid Assessment: Unity State, South Sudan,’ August 2022; UN Peacekeeping, ‘Leer County: Relative calm resumes after waves of brutal violence, but humanitarian situation dire,’ 6 May 2022 Between November 2021 and July 2022, ACLED records 110 attacks or armed clashes involving these actors in and around Leer county (see map below), which resulted in over 290 reported fatalities, with 180 fatalities in April alone. Adding to this unrest, historic flooding in 2019, 2021, and 2022 has transformed Unity State. The massive IDP camp in Bentiu that houses over 100,000 people has become even more overcrowded as people have attempted to flee the floods.30Wendy MacClinchy, Dan Mahanty, and Stefan Bakumenko, ‘To Stem the Tide: Climate Change, UNMISS, and the Protection of Civilians,’ Center for Civilians in Conflict, August 2024; International Organization for Migration, ‘South Sudan: Bentiu IDP Camp Population Count (October 2024),’ October 2024 Desperate inhabitants have become an important base for political support and armed recruitment by rival factions. Today, Nuer clans still vie for loot and political power at each other’s expense while Leer county remains a hotspot for attacks against civilians and widespread sexual violence.31Africanews, ‘Dozens killed in violence in volatile Unity State in South Sudan,’ 13 August 2024

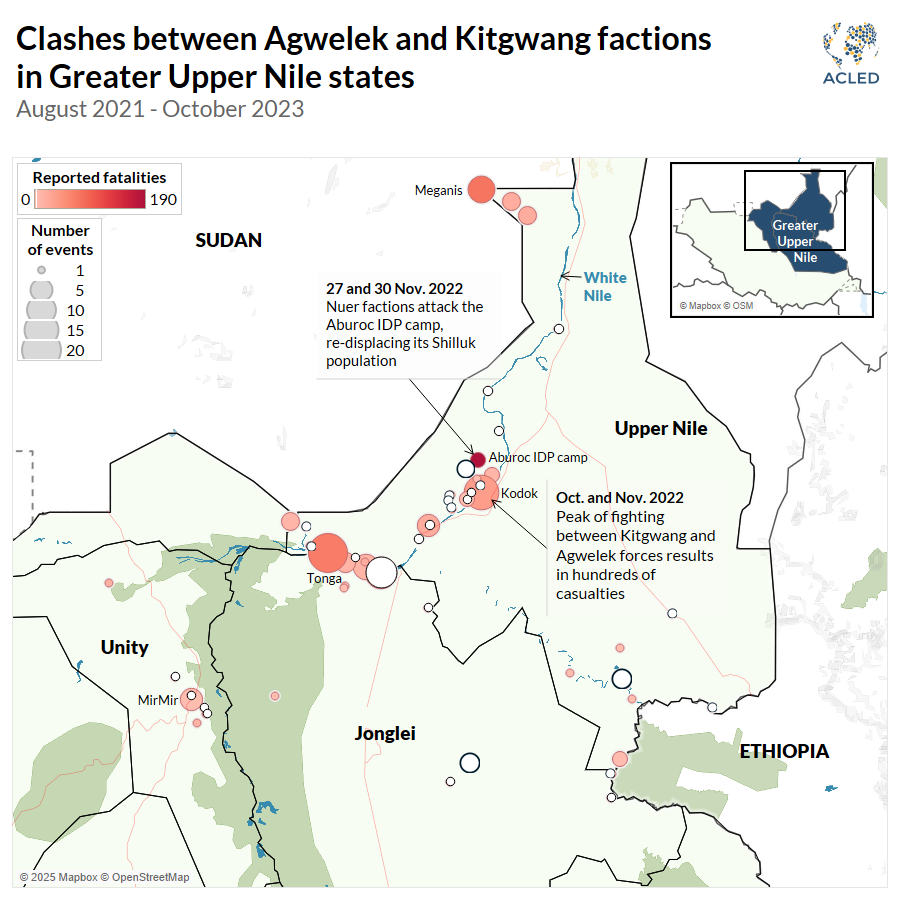

Finally, all three states are affected by a showdown between two SPLM-IO splinter factions that are facing off along the White Nile river for control of the land.32MSF, ‘Conflict in Greater Upper Nile impedes assistance to people already devastated by flooding,’ 21 October 2022 As General Simon Gatwech’s Kitgwang armed group recruits from and operates alongside the Nuer-dominated SPLM-IO and White Army, General Johnson Olony’s mainly Shilluk Agwelek forces have government support.33Joshua Craze, ‘Upper Nile Prepares to Return to War,’ Small Arms Survey, March 2023 Between August 2021, when the campaign of violence began, and October 2023, ACLED records nearly 550 civilian and combatant fatalities arising from at least 54 violent events involving these actors (see map below). During the peak of this violence in the Kodok area between August and December 2022, UNMISS and the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights reported that 258 people were abducted and 62,000 displaced.34UNMISS, ‘South Sudan: UN Report finds nearly 600 civilians were killed amid gross human rights abuses and serious violations of international humanitarian law by armed groups in Greater Upper Nile in late 2022,’ 1 December 2023 On 27 and 30 November 2022, this Nuer coalition attacked the Aburoc IDP camp in Upper Nile state’s Fashoda county, once again displacing the camp’s entire Shilluk population.35Solidarités International, ‘South Sudan – Aburoc : Thousands of Civilians Flee the Advancement of Armed Groups,’ 5 December 2022; UNOCHA, ‘South Sudan: Upper Nile Flash Update No. 1, as of 10 December 2022,’ 10 December 2022 As both a contest for local power and a proxy conflict between Juba and Upper Nile’s Nuer factions, the Agwelek-Kitgwang rift remains fundamentally unresolved and could re-escalate into violent campaigns along the White Nile.

Despite a deadly governmental offensive against the Shilluk in 2017 and ongoing Dinka colonization along the White Nile at the Shilluk’s expense, the largely Shilluk Agwelek are effectively allied with Kiir’s Dinka-dominated government in Juba against the largely Nuer Kitgwang.36Amnesty International, ‘South Sudan: “It was as if my village was swept by a flood”: Mass displacement of the Shilluk population from the West Bank of the White Nile,’ 21 June 2017; Joshua Craze, ‘Displaced and Immiserated: The Shilluk of Upper Nile in South Sudan’s Civil War, 2014–19,’ Small Arms Survey, September 2019; Joshua Craze, ‘Upper Nile Prepares to Return to War,’ Small Arms Survey, March 2023 This is part of a broader, post-R-ARCSS campaign whereby Kiir’s central government uses allies and community militias to carry out violence while trying to detach factions from Machar’s SPLM-IO.37International Crisis Group, ‘South Sudan’s Splintered Opposition: Preventing More Conflict,’ 25 February 2022 This poorly hidden process frequently turns into indiscriminate violence against entire communities, as seen with the attack on the Aburoc IDP camp, while allowing Kiir and other power players to claim that ethnic, intercommunal, or local violence is wholly responsible for South Sudan’s continued insecurity. And yet, even in this proxy clash in which Kiir and Machar are supposedly no longer at war, ACLED records 100 clashes between their forces, resulting in at least 188 reported fatalities in Greater Upper Nile alone since the R-ARCSS was signed.

A stagnant peace process and continued violence

The R-ARCSS has changed many actors’ political calculus but has not brought peace to South Sudan. Much of this proxy warfare and political jostling are influenced by the prospect of elections and a post-transition government in South Sudan. The election postponement is a violation of Article 199 of the R-ARCSS, which states that the 2011 Transitional Constitution can only be amended after the Legislature is given a month to deliberate, rather than the one day that was offered.38Luka Biong Deng, ‘What Could End the Long Postponement of South Sudan’s First Elections?,’ International Peace Institute, 15 October 2024 Though one survey using random household sampling conducted between March and June 2024 found 71% of respondents across all 10 states believed South Sudan was ready for elections, the postponement is indicative of parties’ structural alienation from their formal commitments outlined in the R-ARCSS.39David Deng, et al., ‘Elections and Civic Space in South Sudan: Findings from the 2024 Public Perceptions of Peace Survey,’ Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung, June 2024; UNSC, ‘Final report of the Panel of Experts on South Sudan submitted pursuant to resolution 2633 (2022),’ S/2023/294, 26 April 2023 The postponement is unlikely to result in new violence but will likely ensure the continuation of existing violent rivalries into 2025 and beyond, typified by the gun battle that erupted in Juba in November 2024 when President Kiir attempted to arrest his influential longtime spy chief, General Akol Koor Kuc.40Benjamin Takpiny, ‘4, including civilians, killed in attempt to arrest South Sudanese former chief,’ Anadolu Agency, 11 November 2024 Elections would have tested whether South Sudan’s political ecosystem could withstand a contentious and repressive national election instead of relapsing into civil war.

In 2025, Greater Upper Nile will continue to be afflicted by mass displacement, poverty and hunger, environmental degradation, and tit-for-tat violence that frequently spirals out of control. As political positions and state salaries replaced, undermined, or supplemented traditional modes of authority, politicians and generals have built coalitions less with political ideology and policy plans than with paternalist networks and the promise of gaining at the expense of others.41International Crisis Group, ‘Toward a Viable Future for South Sudan,’ 10 February 2021 Sociopolitical factions rely on heavily militarized ethnic differentiation to mobilize voters, soldiers, and financiers.42Kon Madut, ‘Ethnic Mobilization, Armaments, and South Sudan’s Quest for Sustainable Peace,’ Peace Review: A Journal of Social Justice, 19 January 2021 Contrary to narratives of anarchy and tribalism, this process reflects highly contemporary challenges of political corruption and paternalism, unregulated capital accumulation, and weapons proliferation and impunity. Indeed, the various parties in Greater Upper Nile all have their own definitions of peace and justice and often violent ways of achieving them. In a region in transition like Greater Upper Nile, both change and the status quo are costing lives.

Visuals produced by Ana Marco.