Germany’s political polarization spills into the streets ahead of federal elections

17 February 2025

Since Chancellor Olaf Scholz’s center-left coalition collapsed over budget squabbles and a lost confidence vote on 16 December 2024, Germany has entered an unusually tense campaign ahead of snap elections on 23 February 2025.1ZDF, ‘Bundespräsident Steinmeier löst Bundestag auf,’ 27 December 2024 The country’s political arena has moved away from long-standing centrism toward heightened polarization — a shift that is also felt in the streets. Just weeks before the elections, hundreds of thousands protested nationwide after the center-right Christian Democratic Union party’s Friedrich Merz — the likely next chancellor according to polls — relied on support from the far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD) to push a parliamentary motion for tougher migration laws.2Spiegel, ‘Hunderttausende demonstrieren in ganz Deutschland gegen rechts,’ 3 February 2025 Although the bill was ultimately rejected and Merz ruled out any coalition with the far right, it nonetheless breached a post-war norm observed by Germany’s mainstream parties referred to as the ‘firewall,’ whereby collaboration with far-right forces was consistently avoided.3Jens Thurau, ‘Nach Asyl-Abstimmung: Was ist die “Brandmauer”?,’ Deutsche Welle, 30 January 2025

Long seen as Europe’s engine of stability and growth, Germany is grappling with mounting challenges. A sluggish post-pandemic recovery, rising populism, and entrenched urban-rural and East-West divides have fueled discontent and polarization. Meanwhile, infighting among members of the ruling coalition and reignited debates over energy, immigration, and foreign policy have sparked street activism and bolstered the opposition.4Henrik Böhme, ‘Germany: The return of the ‘sick man’ of Europe?,’ Deutsche Welle, 1 August 2023; James Angelos, ‘Germany’s rude political awakening,’ Politico.eu, 29 January 2024; Tim B. Peters, ‘Between scandals, election successes and court judgements – the AfD in 2024,’ Konrad Adenauer Stiftung, 13 December 2024 The AfD, in particular, is gaining ground, with polls projecting it as the second-strongest parliamentary force in the upcoming elections.5Sabine Kinkartz, ‘German election: Focus on immigration and the economy,’ Deutsche Welle, 10 January 2025; Politico, ‘Germany – 2025 general election,’ 29 January 2025

Amid such polarization, national vote season appears to be an increasingly perilous time for German politicians. The 2024 European Parliament election campaign offered a worrying preview, as it was marred by a spate of aggressions against local centrist party officials, candidates, and campaign volunteers, while revealing a larger pattern of violence targeting politicians across the spectrum.6Maik Baumgärtner et al., ‘Why Are Attacks and Incitement on the Rise in Germany?,’ Spiegel, 13 May 2024 Looking at both last year’s European vote and the high-stakes federal election on 23 February, this piece explores how rising polarization has intensified street activism in the form of demonstrations, both against far-right parties and government policies; it also considers whether polarization is contributing to an uptick in political violence, particularly amid the mounting tensions surrounding national elections.

Germany’s polarized streets

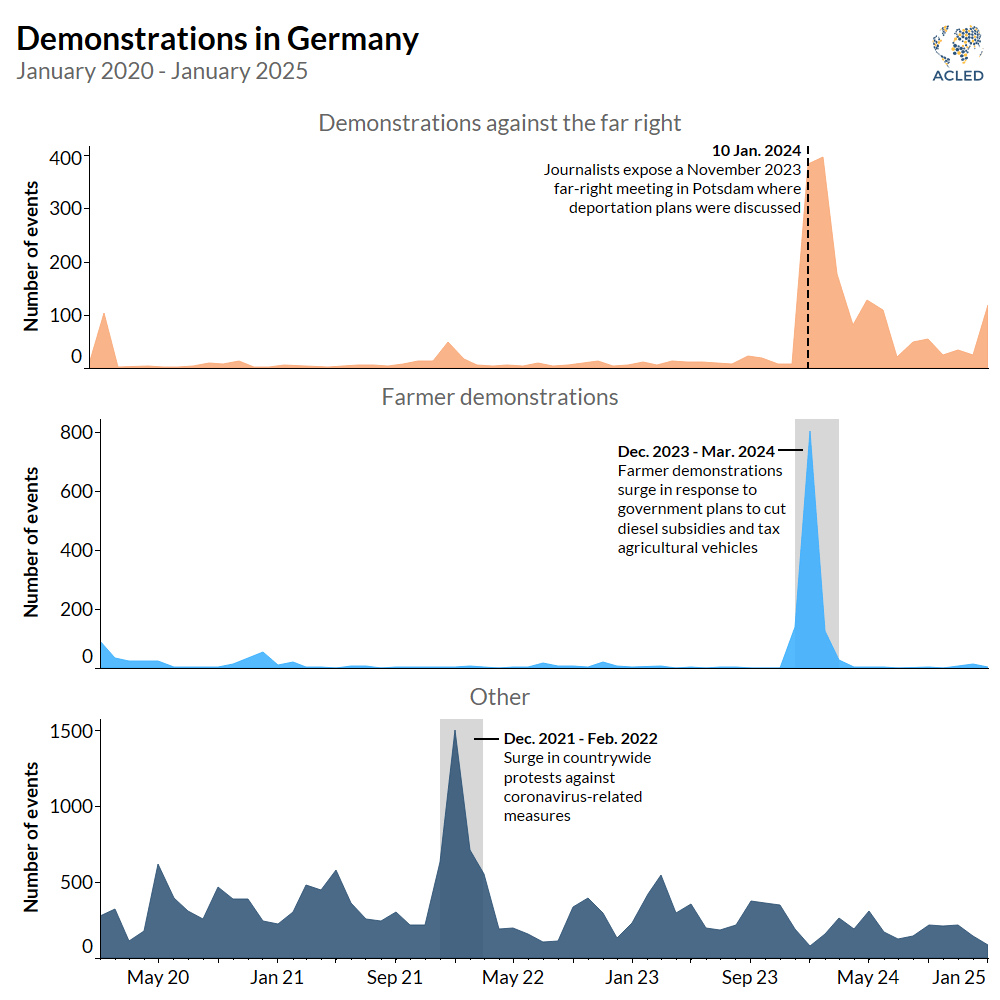

Popular mobilization in Germany increased in 2024, with ACLED recording a 17% rise to over 4,650 distinct demonstration events. The year’s protest trends mirrored deepening polarization in German society, with entrenched opposition to the far right and the outgoing center-left government. Throughout 2024, ACLED records over 1,450 demonstrations in opposition to right-wing extremism. These events, predominantly led by grassroots civil society groups and centrist parties, have particularly focused on the AfD after revelations of a secret far-right meeting in Potsdam in November 2023 (see graph below), where plans to deport foreigners and citizens who they called “unassimilated” were discussed.7Thomas Escritt and Andreas Rinke, ‘Far-right party denies backing deportation of ‘unassimilated’ Germans,’ Reuters, 16 January 2024; Marcus Bensmann et al., ‘Secret plan against Germany,’ Correctiv, 15 January 2024 The backlash to this is still reverberating into 2025. It also made 2024 the most active year for anti-extremism demonstrations since ACLED began tracking Germany in 2020. Despite a 20% drop compared to 2023, far-right protests continued to tap into a set of recurring themes — opposition to immigration, particularly after high-profile incidents involving foreigners,8Deike Dining, ‘So viel Hass,’ Spiegel, 28 January 2025; Georg Schwarte, ‘Wie die Tat den politischen Diskurs verändert hat,’ Tagesschau, 28 January 2025 skepticism of military aid to Ukraine,9Guy Chazan, ‘Germany’s ‘peace chancellor’ spars with rivals over Ukraine,’ Financial Times, 6 December 2024 and opposition to the federal government’s policies — some of which have proved instrumental in the AfD’s electoral successes in the eastern states of Thuringia, Saxony, and Brandenburg in September 2024.10ZDF, ‘Woidke sichert SPD-Erfolg vor AfD,’ 22 September 2024; Hans Pfeifer, ‘Germany: AfD adds to string of successes in Brandenburg,’ DW, 24 September 2024

Polarization in 2024 stretched beyond political battles over far-right ideas, manifesting into broader unrest and growing frustration with Scholz’s coalition, which was chided for both its policies and perceived inaction. The urban-rural divide took center stage as farmers mobilized en masse and led over 980 protests11James Angelos, ‘Germany’s rude political awakening,’ Politico.eu, 29 January 2024 — more than six times the annual average — against subsidy cuts and tax hikes (see graph above). Labor unrest, exemplified by the November and December 2024 strikes over layoff fears and contract renewals that shook the country’s powerful automotive sector,12Maria Martinez and Matthias Williams, ‘Workers launch strikes as Germany frets over industrial future,’ Reuters, 29 October 2024 followed closely, recording over 770 recorded events. For their part, environmental activists held over 490 demonstrations, in most cases campaigning on local issues or demanding stronger action on Germany’s contentious energy future,13Barbara Tasch, ‘Cost of going green sparks backlash from Europe’s voters,’ BBC, 5 June 2024 despite the Greens holding a key role in the government.

Political violence is on the rise

In early May 2024, the Social Democratic Party of Germany’s (SPD) candidate in Saxony, Matthias Ecke, was hospitalized with broken bones after being assaulted by four teenagers — two of whom had contact with the local far-right scene14Anne Herzlieb, ‘Tatverdächtiger: rechtsextrem und jugendlich,’ ZDF, 10 May 2024 — while he was putting up election posters in Dresden.15Paul Hockenos, ‘Politics Is Especially Violent in Germany,’ Foreign Policy, 6 June 2024 About a month later, on 8 June 2024, a group of hooded people assaulted and slightly injured two AfD councilors and another person in front of a cafe in the center of Karlsruhe. The local AfD branch blamed the left-wing radical scene for the attack.16Zeit Online, ‘Zwei AfD-Stadträte in Karlsruhe angegriffen,’ 9 June 2024 These incidents are just some of many directed at local and state politicians, political parties, and election volunteers in the lead-up to last summer’s European election.17Maik Baumgärtner et al., ‘Why Are Attacks and Incitement on the Rise in Germany?,’ Spiegel, 13 May 2024 Verbal and physical attacks on politicians are on the rise in Germany: According to data released by the Federal Criminal Police Office, they more than doubled between 2019 and 202318Deutscher Bundestag,’Angriffe auf Politiker, Parteibüros und Wahlplakate bis einschließlich 2023,’ 26 January 2024; Matthias Janson, ‘Angriffe auf die Politik haben wieder zugenommen,’ Statista, 7 May 2024 and continued to increase — by 20%, according to preliminary data — in 2024.19Rheinische Post, ‘Angriffe auf Amts- und Mandatsträger deutlich gestiegen,’ 4 February 2025

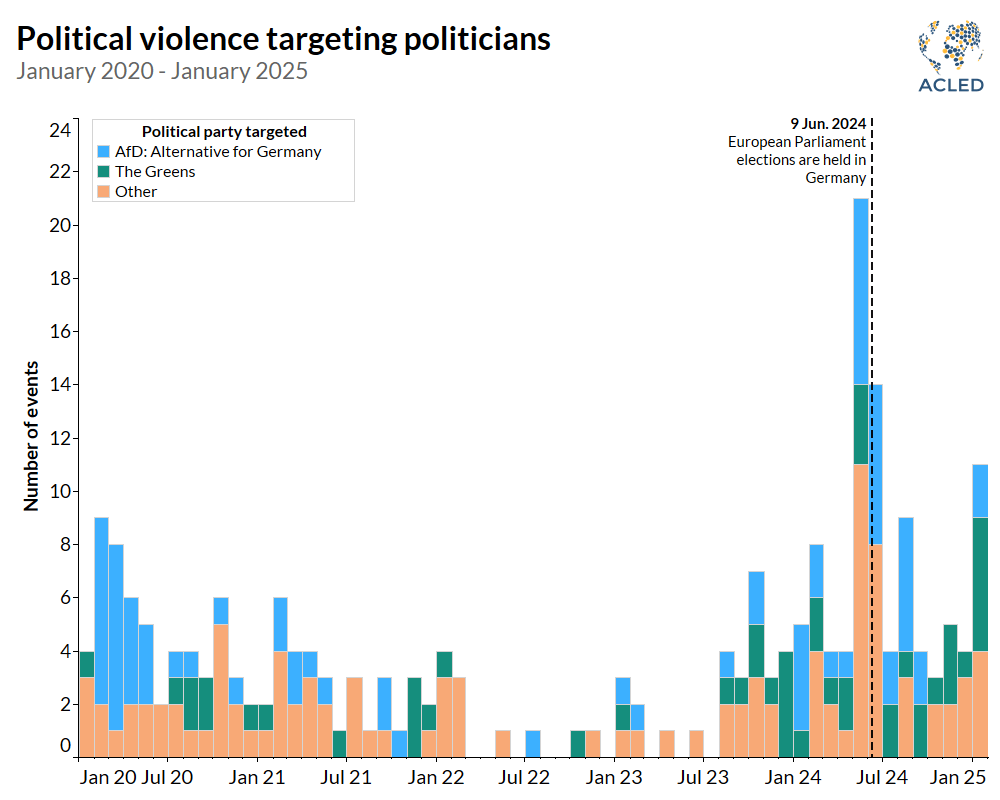

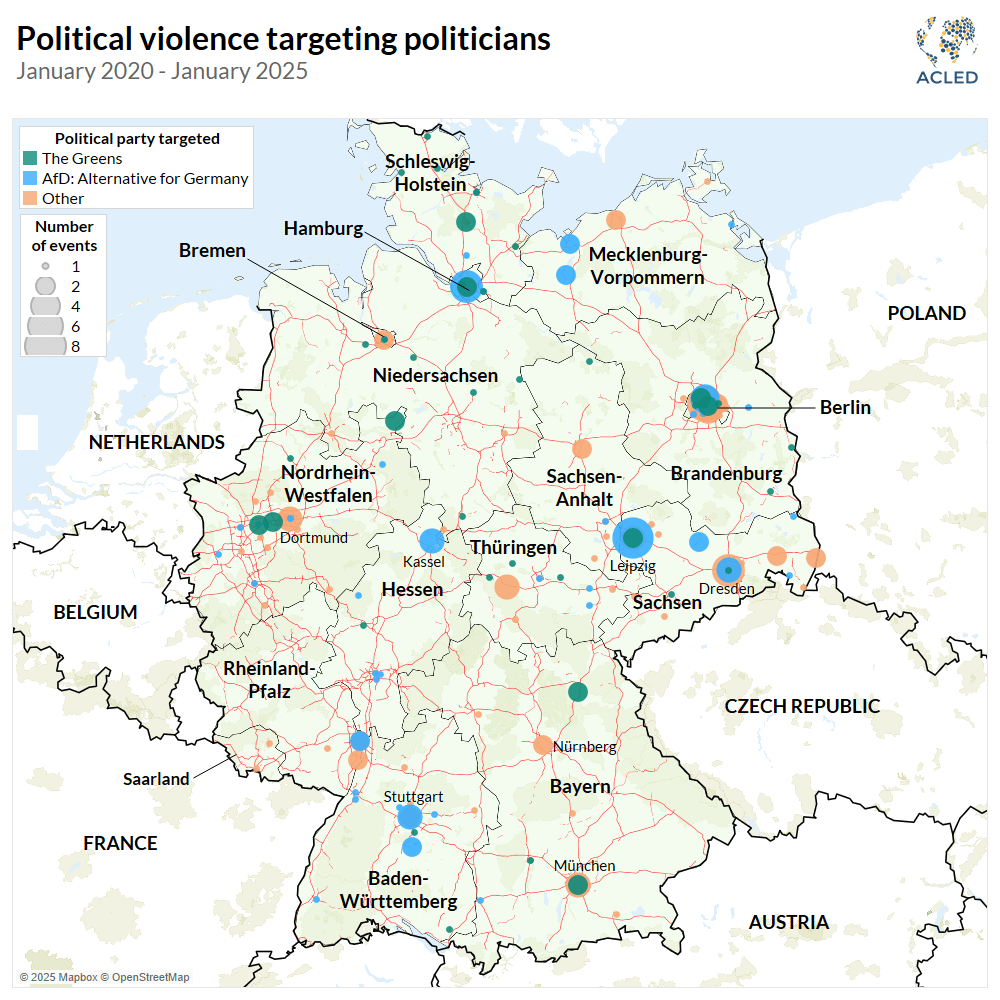

ACLED records at least 85 acts of physical violence targeting politicians and political parties in 15 out of 16 states in 2024. Most attacks involved material damage to properties. Overall, 2024 accounts for the most violence against politicians and political parties since ACLED began monitoring Germany, with nearly three times the yearly average between 2020 and 2023. Attacks peaked around the European elections, with at least 35 events recorded between May and June, making up 41% of the total for the year (see graph and map below).20Paul Hockenos, ‘Politics Is Especially Violent in Germany,’ Foreign Policy, 6 June 2024 Mainstream and centrist parties blame the rhetoric of the far right, especially the AfD, for the rise in violent confrontations. Data show that the entire spectrum of Germany’s political landscape has been subjected to acts of violence, with the AfD and the Greens emerging as the most frequently targeted parties.21Mathias Hammer, ‘German chancellor condemns spate of violence against politicians ahead of June elections,’ Semafor, 8 May 2024

The collapse of Germany’s three-party coalition government inaugurated a brief yet polarized electoral campaign. Intimidation and attacks against politicians and parties spiked again after the dissolution of parliament, with a reported 11 events in January 2025 alone, up from a monthly average of five events recorded between August and December 2024. Most attacks inflicted damage to parties’ offices and, in a few cases, election stands. This uptick appears to offer further evidence that elections have increasingly become an arena where political violence tends to be on the rise.

Peering through the firewall’s cracks

Just like many other world democracies, heightened divisions seem to have become the new normal in German politics.22Andrea Carboni, Kieran Doyle, and Ana Marco, ‘The Year of Elections Was Also a Year of Electoral Violence,’ World Politics Review, 24 January 2025 Fear of the rise of the far-right, epitomized by the outrage over the leaked remigration plan, as well as fierce opposition to health, economic, and migration policies, have precipitated a climate of political polarization in Germany and across Europe. In this context, radical forces across the political spectrum feel less constrained from using violence and intimidation against political opponents. Public authorities have warned against the rise in political violence, describing it as a threat to democracy itself.23Silvia Ayuso, Almudena de Cabo, and Juan Navarro, ‘La oleada de agresiones a políticos desata la alarma en Europa: “Me atacaron de forma repentina e inesperada”,’ El País, 12 May 2024 Current election polls in Germany suggest that such trends are unlikely to fade away any time soon.

The AfD is projected to secure twice the representation in the upcoming German parliament compared to the 2021 federal elections, consolidating its second place behind the Christian Democratic Union. Its growing popularity comes even though the party is classified as an extremist right-wing organization in several German states and on the national level is a suspected extremist organization due to what two state courts confirmed to be anti-constitutional rhetoric,24Markus Balser and Christoph Koopmann, ‘”Der Rauchmelder der Verfassung schrillt,”’ Süddeutsche Zeitung, 13 May 2024 allowing Germany’s federal domestic intelligence agency to monitor the party’s activities.25Pierre Emmanuel Ngendakumana, ‘Germany’s domestic intelligence agency can continue to surveil far-right AfD, high court rules,’ Politico, 13 May 2024 Amid squeezing support for centrist mainstream parties, radical forces on both the right and the left may increasingly resort to unconventional means to advance their agendas.

Visuals in this report were produced by Ana Marco