Watch the recorded webinar examining the important shifts leading to SAF’s advances, and the impact this new phase of war will have on the dynamic of the conflict.

After 23 months of war, on 21 March, the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and its allies regained control of the presidential palace in central Khartoum, along with all the ministries and government buildings surrounding it. As the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) troops withdrew from Khartoum city — a move the group called strategic — the SAF announced full control of Sudan’s tri-city capital on 26 March.1Sudan Tribune, “Sudan RSF leader says Khartoum withdrawal tactical,” 30 March 2025 The recapture of Khartoum city thus marks a watershed moment in the conflict: The SAF has now gained the upper hand, particularly in central Sudan.

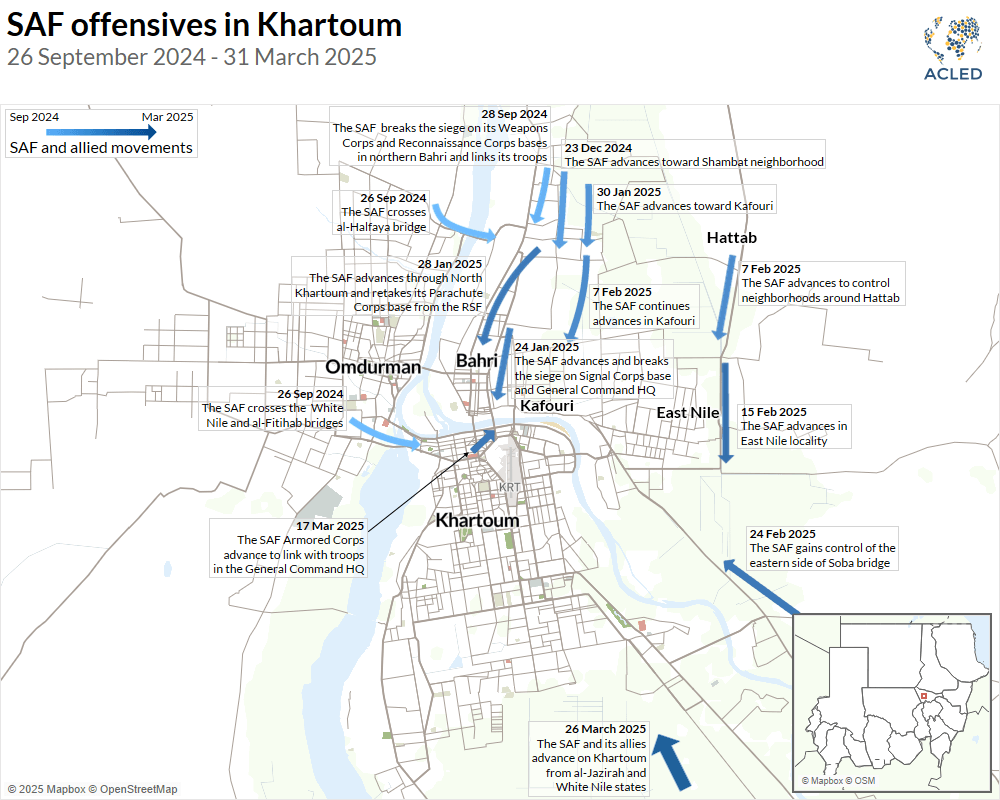

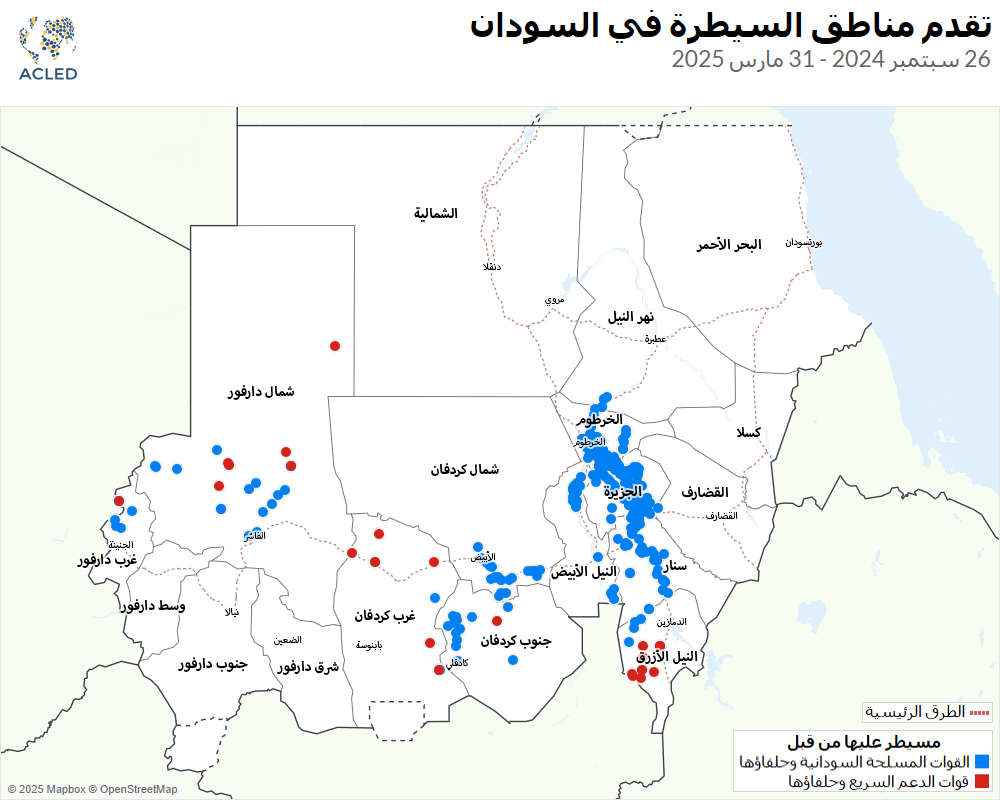

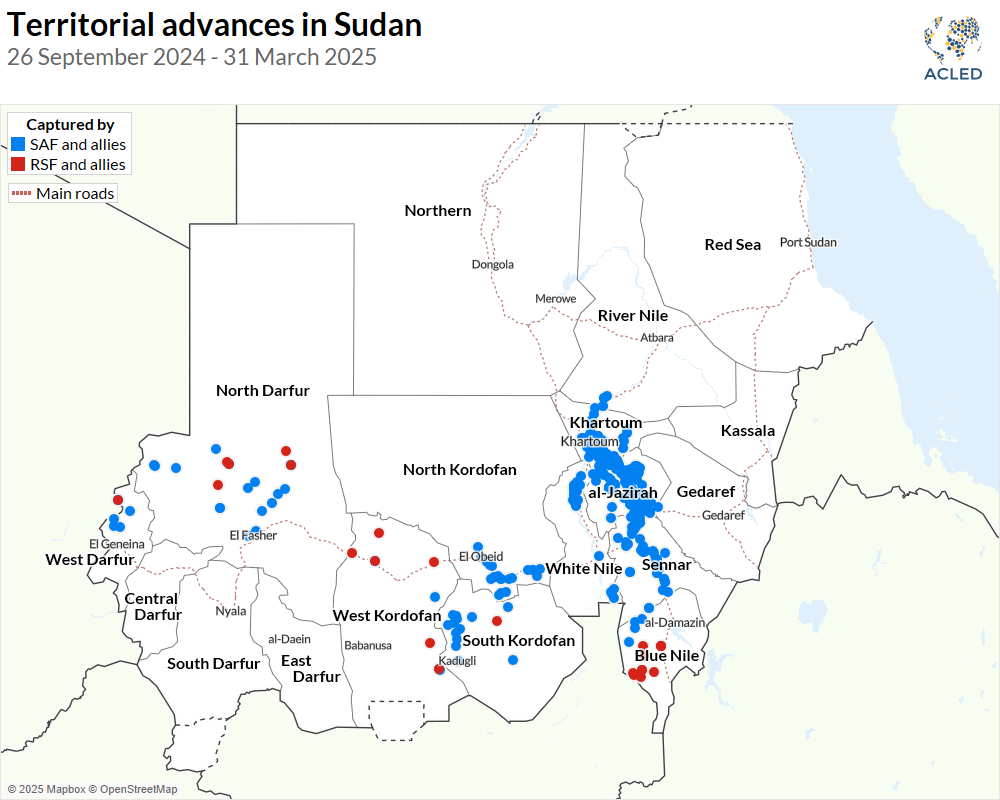

Though Khartoum’s fall may seem to have unfolded quickly to casual observers, it represents the culmination of an offensive that began at the end of September 2024 with coordinated attacks on RSF-held positions in the tri-cities of Khartoum state — Bahri, Omdurman, and Khartoum cities. The SAF also recaptured the capital cities of Sennar and al-Jazirah states, forcing the RSF into an increasingly defensive position in Khartoum. The SAF’s campaign eventually ousted the RSF from central Sudan, breaking their siege on several SAF bases in Khartoum, Sennar, and North Kordofan states and cutting vital supply routes, leaving RSF troops surrounded by the SAF in central Khartoum. Overall, since the offensive began, the SAF and its allies have regained over 430 locations across central and southern Sudan (see map below).

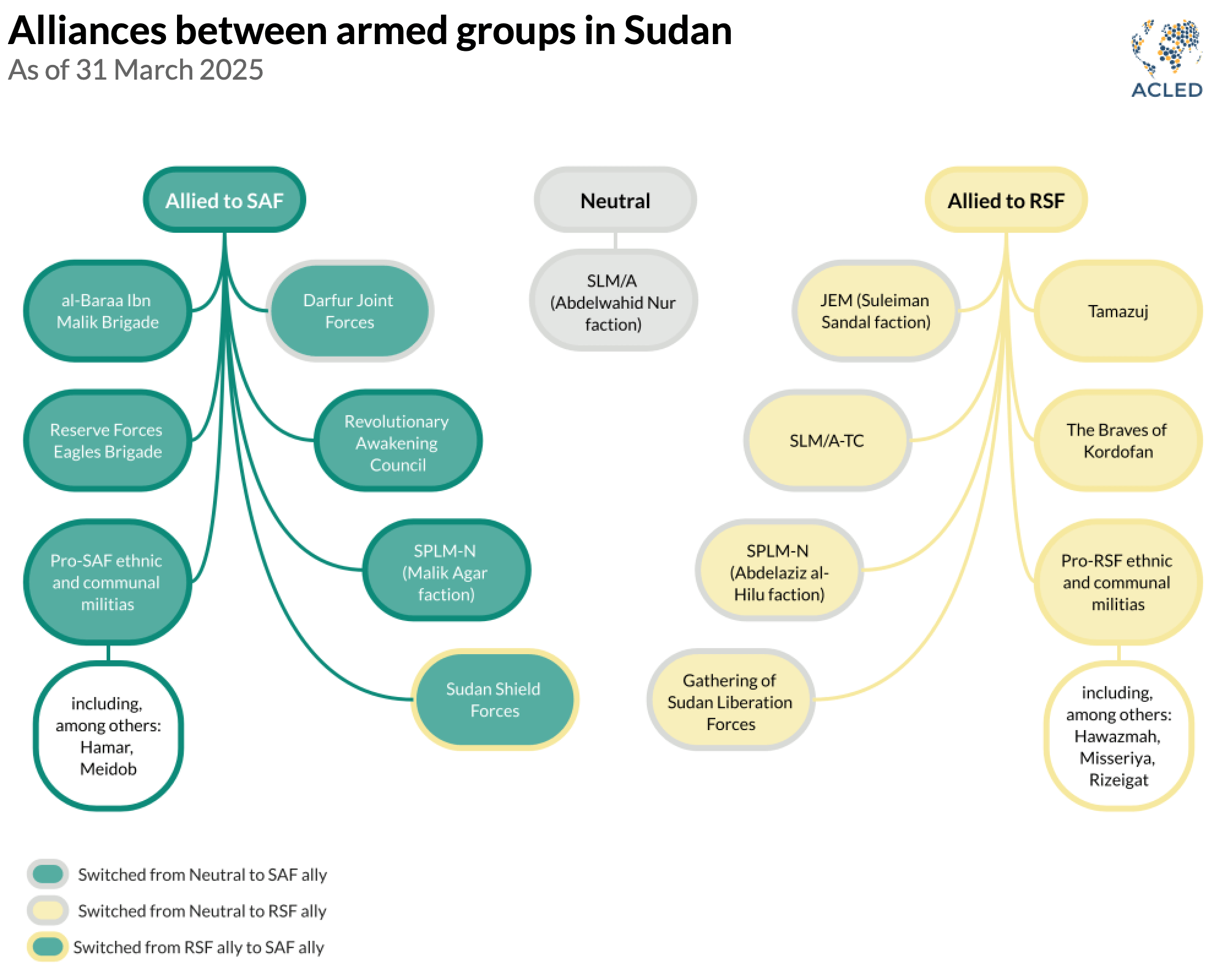

While foreign meddling has facilitated the SAF’s advances,2Aidan Lewis, “Sudan’s conflict: Who is backing the rival commanders?” Reuters, 12 April 2024; Khalid Abdelaziz, Parisa Hafezi, and Aidan Lewis, “Sudan civil war: are Iranian drones helping the army gain ground?” Reuters, 10 April 2024; Voice of America, “SAF, RSF Conflict Threatens Sudan’s Eastern Border,” 1 February 2024; Sudan Tribune, “Russia offers ‘uncapped’ military aid to Sudan,” 30 April 2024; Andrew McGregor, “Russia Switches Sides in Sudan War,” The Jamestown Foundation, 8 July 2024; United Nations Security Council, “Final report of the Panel of Experts on the Sudan,” 15 January 2024; Middle East Monitor, “Khartoum again accuses UAE of supporting Rapid Support Forces,” 15 October 2024 three important shifts within Sudan’s warring camps played a critical role in shifting the tide: the SAF’s enhanced recruitment to address a chronic manpower shortage, the emergence of new alliances between armed groups, and the fragmentation of the RSF. While some areas of Khartoum state remain contested, especially in the west and south of Omdurman, the war in Sudan enters a new phase.

From defense to offense: The SAF’s military advances

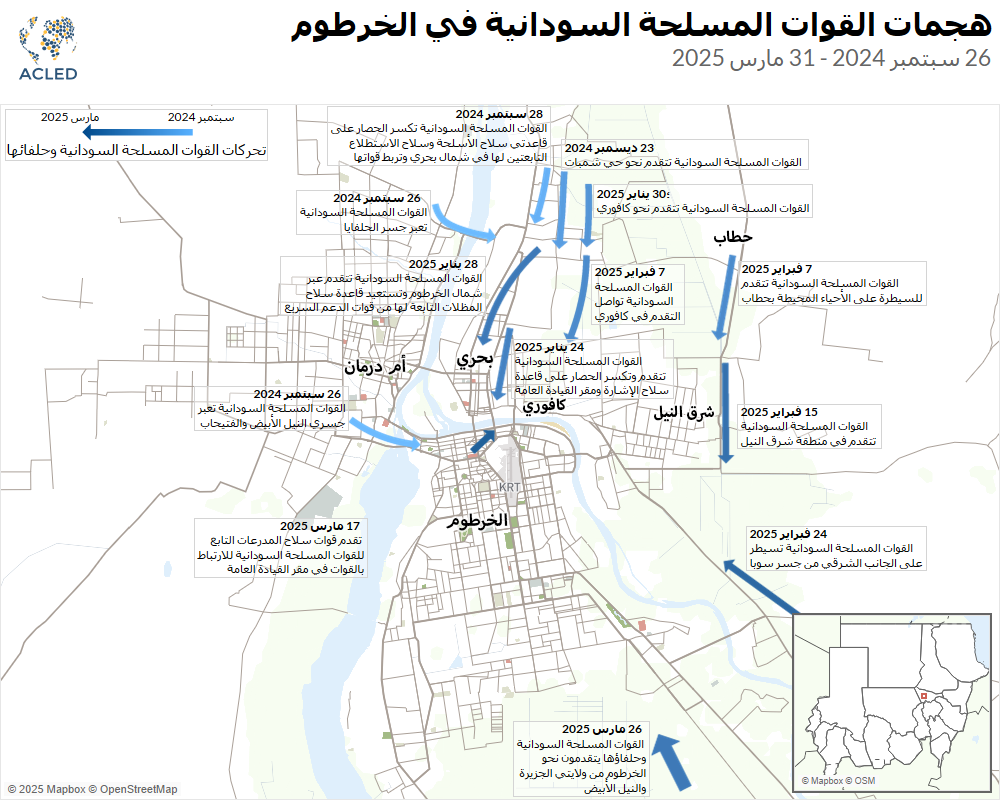

When the SAF launched its offensive operation on 26 September, soldiers at every base in Khartoum moved on RSF positions in the tri-cities of Khartoum state (see map below). Supported by air cover and artillery fire, SAF infantry troops advanced eastward to oust the RSF from Khartoum. The SAF strategy to re-take Khartoum focused on three maneuvers: linking besieged troops in Khartoum, Sennar, and Kordofan; cutting off the RSF’s supply lines; and encircling the RSF in central Khartoum by mobilizing from the neighboring White Nile and al-Jazirah states.

When the conflict broke out on 15 April 2023, the RSF besieged most of the SAF bases in Khartoum. This restrained the SAF from using the full capacity of its bases to fight the RSF. The first strategy of the SAF was to end the sieges on its bases in Khartoum. Accordingly, on 28 September, the third day of the offensive operation in Khartoum, the SAF broke the siege on the Weapons Corps and Reconnaissance Corps bases in northern Bahri. After lifting the siege on these bases, the troops joined other SAF units in the fight to oust the RSF from Khartoum and neighboring states. The process of breaking these sieges would take them several months to conclude, and the RSF’s 21-month siege on the General Command Headquarters3The headquarters comprises five main buildings — the Army Headquarters, Navy Command, Air Force Headquarters, Military Intelligence, and the Ministry of Defence. in the heart of Khartoum was finally broken on 24 January. This freed up many SAF units and positioned them for the fight in downtown Khartoum.

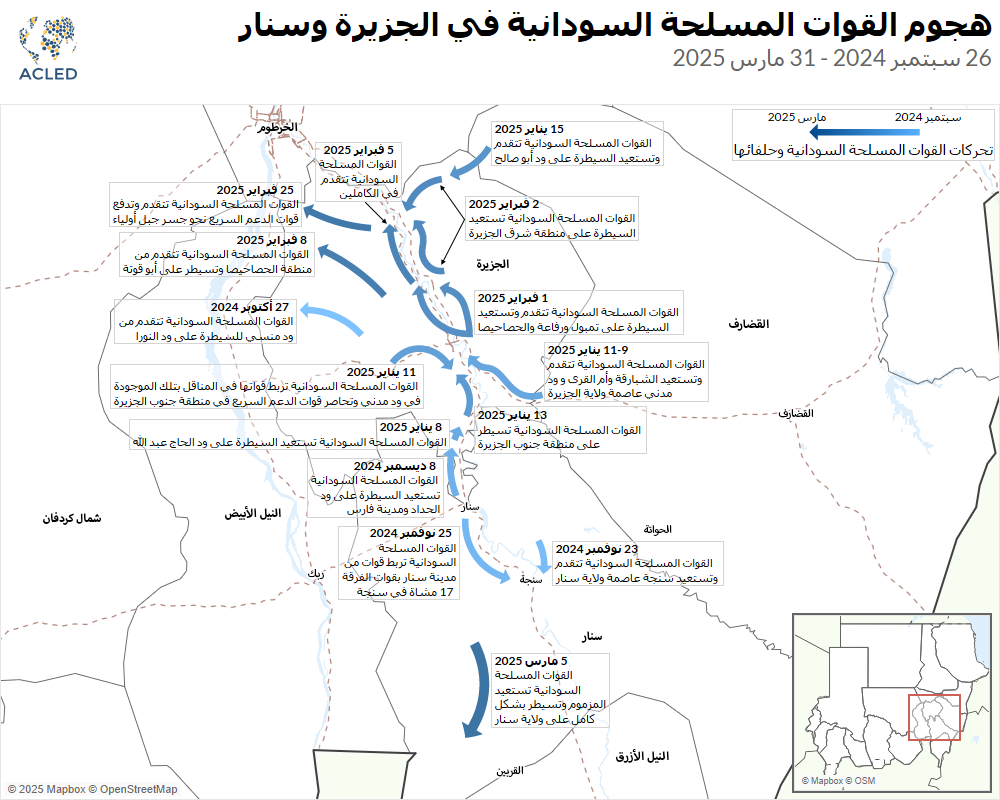

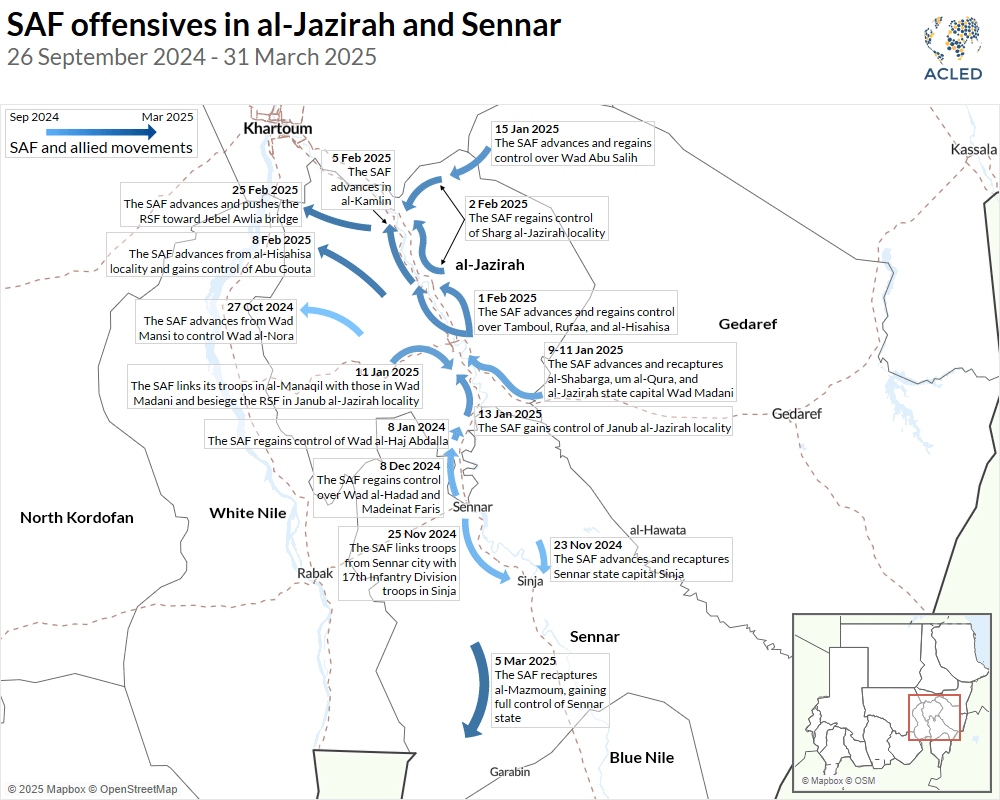

Outside Khartoum, the SAF deployed a similar focus to Sennar and al-Jazirah states. On 5 October, the SAF linked its forces in Sennar city with those in White Nile state, and on 23 November, the SAF and its allies broke the siege on the capital Sinja (see map below). Most of Sennar eventually fell to the SAF by the beginning of 2025. By the end of March, the SAF also claimed full control of al-Jazirah state. Alongside each base launching an offensive operation, the SAF and its allies began advancing into Khartoum from the adjacent al-Jazirah and White Nile states, effectively encircling the RSF in downtown Khartoum. The SAF resorted to drone strikes and missiles targeting any RSF reinforcements in downtown Khartoum.

Correction | 17 April 2025: The first version of this map incorrectly labeled the dates for the 25 Nov 2024 and 23 Nov 2024 annotations as 2025.

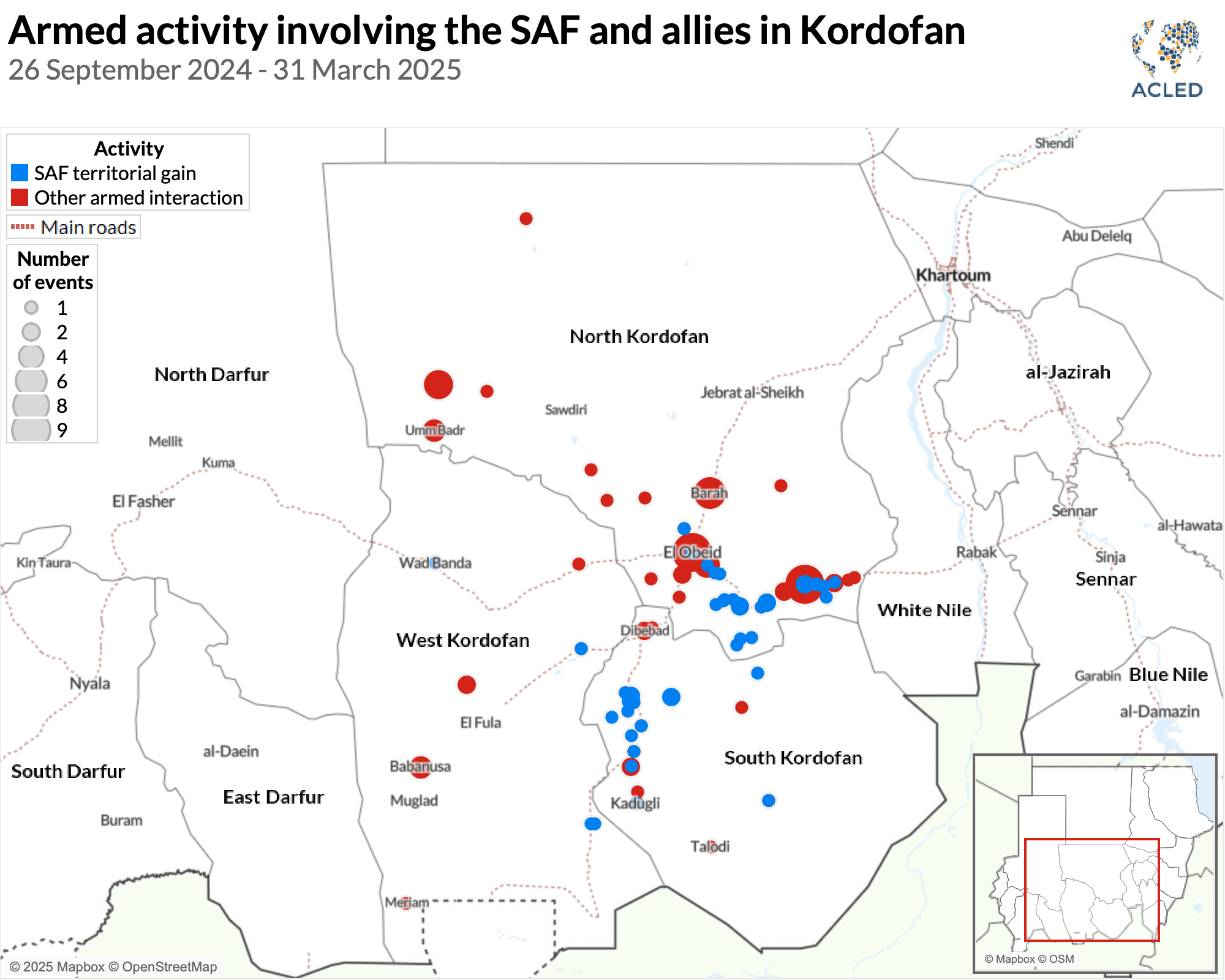

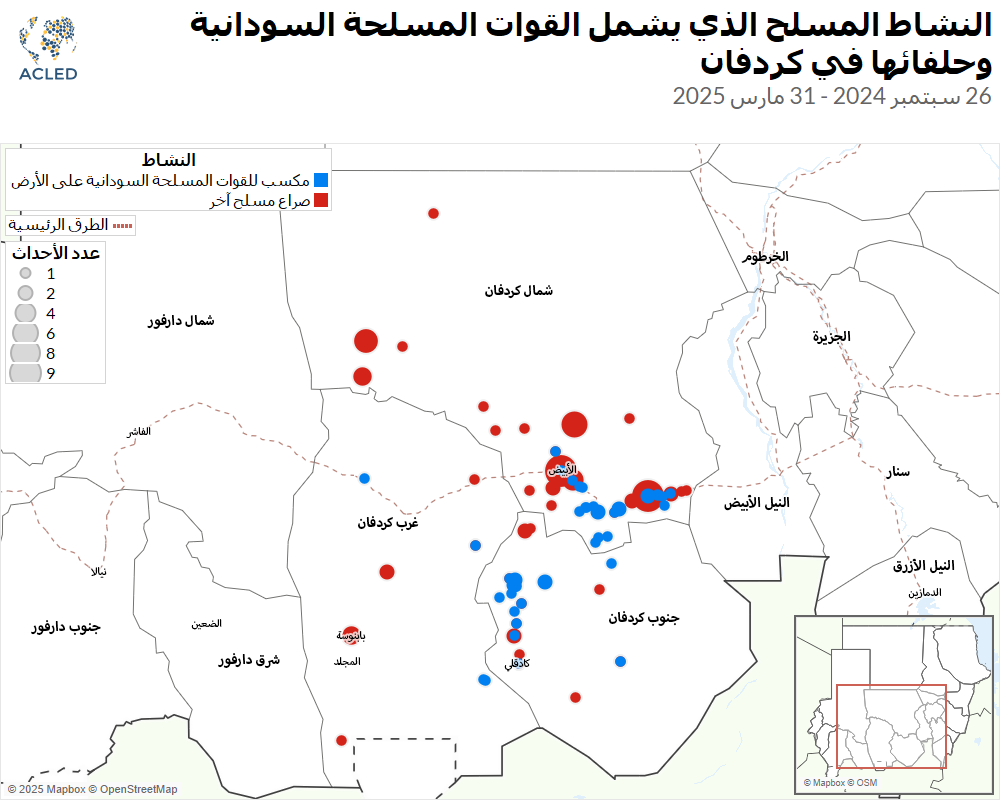

The SAF’s offensive operations expanded to Kordofan in late January, aiming to disrupt the RSF’s military supply lines, like troops, from Darfur to central and southern Sudan (see map below). On 23 February, the SAF partially broke the siege on North Kordofan’s capital city, El Obeid, which serves as the base for its Fifth Infantry Division. The next day, the SAF also partially broke the siege on Dilling city in South Kordofan from the south and managed to link its 54th Infantry Brigade with its forces in the capital, Kadugli city. Since June 2023, the city has been surrounded by the RSF troops in the east and north, while the Abdelaziz al-Hilu faction of the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement-North (SPLM-N) surrounded the city from the west and south.

The SAF’s three-pronged strategy has largely proven effective. The RSF still controls parts of western and southern Omdurman but the SAF and its allies gained complete control of Bahri on 3 March and Khartoum city on 26 March. And while the SAF has so far been unable to wrest the west side of El Obeid from the RSF, partially breaking the siege of the city represents a significant milestone due to its strategic position linking Kordofan and Darfur states — the stronghold of the RSF — with Khartoum and other central states.

During the current offensive, the SAF disrupted the RSF’s attempts at consolidating their rule in Darfur, a region that the RSF has largely controlled, save for North Darfur state, since November 2023. The SAF continued its airstrikes to the west of the country, targeting the RSF positions across all Darfur states. In March, the SAF targeted areas in Darfur where the RSF and its allies were believed to have been holding meetings. Since 22 February, the RSF and its allies have been laying the groundwork to establish a parallel government in the RSF-controlled territories to seize diplomatic legitimacy from the SAF-led government, which is currently based in the Red Sea state.4Khalid Abdelaziz, “Sudan parallel government offers route to diplomatic leverage and arms for RSF,” Reuters, 28 February 2025 To disrupt this process, the SAF targeted various locations. In South Darfur’s capital, Nyala, the SAF targeted the Nyala Airport on 13 and 14 March. The SAF claimed to have killed an unidentified number of RSF troops. The next day, on 15 March, drone strikes by the SAF targeted a hotel in Nyala, injuring 10 RSF-allied politicians. Similarly, the SAF airstrikes targeted the East Darfur government headquarters in al-Daein, East Darfur. There were no casualties. Reports indicated that both al-Daein and Nyala cities had hosted meetings between the RSF and its allies to discuss the formation of a parallel government in the RSF-controlled areas.5Sudan Tribune, “Missile strikes hit government buildings in Sudan’s El Daein and Nyala,” 16 March 2025

The SAF strengthens its manpower through recruitment

Since the start of the war, the SAF has prioritized keeping its manpower costs to a minimum, recognizing its troops as a core asset that is difficult to rebuild once lost. It has instead prioritized the use of remote violence, like air and drone strikes, to inflict maximum damage to the RSF without suffering significant losses in its ranks. Overwhelmed by RSF troops, the SAF battle tactics were largely defensive and aimed at depleting the RSF resources and inflicting heavy casualties. This strategy capitalized on the RSF’s “meat grinder” tactics, relying heavily on large frontal assaults and troop density that left them vulnerable to significant losses.

However, the SAF’s limited manpower posed a serious challenge, as the RSF formed a large part of the SAF’s infantry forces before the start of the war. To address this weakness, the SAF turned to recruiting troops, including by offering a general amnesty for RSF defectors who joined the SAF. It also consolidated its forces by withdrawing small battalions and regrouping within major military bases to reinforce strategic positions. This move controversially included withdrawing two major infantry divisions from the cities of Wad Madani and Sinja.

The fall of the al-Jazirah state capital, Wad Madani, to the RSF in December 2023 was a turning point. It pointed to the SAF’s limited ability to contain the RSF because, in two months, five states — Central Darfur, East Darfur, South Darfur, West Darfur, and al-Jazirah — had fallen to the RSF. The SAF could have retained control of Wad Madani but withdrew without providing an explanation — leaving the city and the surrounding area to the RSF.6Middle East Eye, “Sudan: Soldiers accuse army of betrayal after retreat leaves Wad Madani to RSF,” 20 December 2023 RSF troops were accused of looting and killing and raping residents and displaced citizens.7Hudhaifa Ebrahim, “EXCLUSIVE: Murders, Rapes, Hangings Rampant in War-Torn Sudan, Smuggled Birth Control Pills Draw Premium,” The Media Line, 2 January 2024; Strategic Initiative for Women in the Horn of Africa, “Statement: CSOs Condemn the Escalating Violence in Sudan as the War reaches Wad Madani and Al Gezira State,” 24 December 2023 According to the United Nations, more than 500,000 people were displaced from Wad Madani and surrounding areas in the wake of the RSF’s takeover.8UN OCHA, “Sudan Humanitarian Update,” 28 December 2023 This led to criticism of the SAF for failing to protect the city and triggered panic across the remaining SAF-controlled states. As a result, ethnic and communal militias began a mass mobilization against the RSF, reflecting a loss of confidence in the SAF’s ability to defend communities.

Simultaneously, Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, head of the SAF, made a call for a general mobilization against the RSF in January 2024.9Xinhua, “Army chief’s call for arming civilians sparks controversy in Sudan,” 7 January 2024 Thousands of volunteers, alongside traditional leaders and members of native administrations, responded to the SAF’s call to arms.10Youseif Basher, “Sudan: Armed Popular Resistance and Widening Civil Unrest,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 15 February 2024 Following Burhan’s call, training camps were established across northern and eastern Sudan.11European Union Agency for Asylum, “Sudan – Country Focus Security situation in selected areas and selected profiles affected by the conflict,” April 2024 Here, recruits were trained to deploy to the frontlines of Khartoum state, Darfur region, and al-Jazirah state.

The Darfur Joint Forces — a coalition of former Darfur-based rebel groups that signed the Juba Peace Agreement with the transitional government in 2020 — has played a key role in central Sudan and Darfur. When the battle for the capital of North Darfur, El Fasher, erupted in April 2024, the SAF’s Sixth Infantry Division found a strategic ally in the Darfur Joint Forces. Under its ranks, the Zaghawa native administration mobilized troops, declared war against the RSF, and offered a cut-off date for fellow Zaghawa members of the RSF to seek amnesty. The mobilization drive expanded recruitment, as it allowed the SAF to outsource the administrative overhead of training and additional recruitment to its allies, significantly increasing its manpower by integrating fighters with deep local geographical knowledge.

Moreover, after the SAF opened training camps for the Darfur Joint Forces in Kassala and Gedaref states in eastern Sudan,12Sudan Tribune, “Al-Burhan welcomes Darfur groups in ‘Battle of Dignity,’ calls for future integration,” 21 February 2024 recruits joined the military’s fight to regain control of central Sudan. Various groups within the Darfur Joint Forces were deployed to the frontlines in Sennar and Gedaref states, from which they advanced into al-Jazirah state. This strategy was one of the reasons why the SAF was able to overpower the RSF.

Embracing RSF defectors and forging alliances

A second key factor that enabled the SAF’s advances was an alliance-building effort aimed at rallying support among other armed groups. Building on its military intelligence and extensive counter-insurgency expertise, the SAF managed to stoke local rivalries to its advantage and mobilize opposition to the RSF across Sudan.

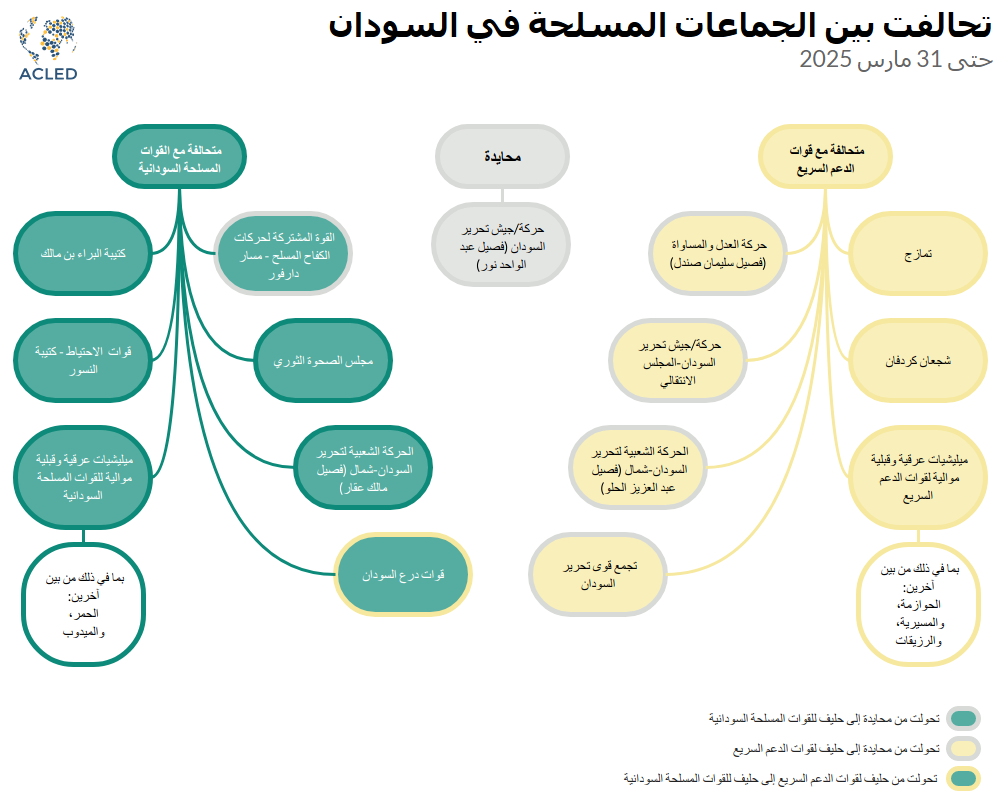

The SAF sought to forge alliances by attracting neutral armed groups or supporting paramilitary groups aligned with the RSF or former President Omar al-Bashir’s regime for tactical and opportunistic reasons. In doing so, it aimed to enhance its indirect territorial control, strengthen its local presence, and ensure broader support for its military and political objectives. Among these groups were the Darfur Joint Forces and the Sudan Shield Forces. The SAF also revived previously dismantled SAF paramilitaries — like the Popular Defense Forces (PDF), al-Baraa Ibn Malik Brigade, and the National Intelligence and Security Service (NISS) combat troops (see visual below). Each of these allies has provided the SAF with unique expertise and geographical advantages.

Darfur Joint Forces

The Darfur Joint Forces is a coalition of five former rebel groups — namely the Sudan Liberation Movement/Army (SLM/A) led by Minni Minawi, the Justice and Equality Movement (JEM) led by Jibril Ibrahim, the Sudanese Alliance, the Sudan Liberation Movement/Army – Transitional Council (SLM/A-TC), and the Gathering of Sudan Liberation Forces (GSLF) — that were active in Darfur between 2003 and 2020 and were appointed to the transitional government as a result of the Juba Peace Agreement in 2020. Four members of the coalition — JEM led by Jibril Ibrahim, the SLM/A Minni Minawi faction, the SLM/A Mustafa Tambour faction, and a faction of the GSLF — announced their support of the SAF in November 2023. This followed the intense ethnic-based clashes that took place in West Darfur in June 2023 and the RSF’s capture of four out of five Darfur states in October and November 2023 and mobilization to control El Fasher, the only Darfurian capital still in the hands of the SAF and its allies (see timeline below).

Major developments involving the Darfur Joint Forces

Apr. 2023 | Former rebel groups establish the Darfur Joint Forces as a neutral body to protect civilians in Darfur

Jun. 2023 | The RSF kills the West Darfur governor and attacks Masalit civilians in West Darfur

Oct. 2023 | The RSF takes over Nyala, the capital of South Darfur

Oct. 2023 | The RSF gains control of Zalingei, the capital of Central Darfur

Nov. 2023 | The RSF takes over El Geneina, the capital of West Darfur, and attacks Masalit civilians

Nov. 2023 | Four members of the Darfur Joint Forces renounce neutrality and announce their support for the SAF

Nov. 2023 | The RSF gains control of al-Daein, the capital of East Darfur

Mar. 2024 | The SLM/A-TC and the GSLF faction led by al-Tahir Hajar split from the Darfur Joint Forces, announcing their neutrality

Apr. 2024 | The SLM/A-TC withdraws from its positions in El Fasher and clashes with the Darfur Joint Forces

Feb. 2025 | The GSLF and SLM/A-TC side with the RSF

In February 2024, the SAF began training recruited fighters from each armed group within the Darfur Joint Forces in eastern Sudan. As thousands graduated, they were deployed to fight with the SAF in the central regions of the country, including Khartoum, Sennar, al-Jazirah, and White Nile states.13Sudan Tribune, “Al-Burhan welcomes Darfur groups in ‘Battle of Dignity,’ calls for future integration,” 21 February 2024 The Darfur Joint Forces’ expertise in rural warfare and desert geography enabled them to support the SAF in launching offensive maneuvers against the RSF across multiple locations. This included initiating battles to “liberate” the al-Gaili oil refinery in rural Khartoum from the RSF. Additionally, they played a role in the fight to gain control of the Omdurman market, which allowed the SAF to link its troops in northern and southern Omdurman within Khartoum and contributed to the SAF’s advances in regaining control over al-Jazirah state, the Fao area in Gedaref state, and other key battlefronts in Sennar state.

The SAF’s advances in the central and southern regions would not have been attainable if the RSF had not been distracted by battles in North Darfur. Without El Fasher — the last remaining Darfur bastion under SAF control — the RSF’s strategic leverage over the entire Darfur region diminishes. The RSF has, therefore, fought persistently to capture the city, maintaining a siege for almost a year and continuously launching attacks. The Darfur Joint Forces has played a crucial role in enabling the SAF to hold El Fasher, launching various maneuvers to disrupt RSF supply routes. These operations have inflicted considerable losses on the RSF, forcing it to deploy thousands of troops to reinforce its frontlines in El Fasher, further weakening its ability to maintain control in other battlefronts.14International Crisis Group, “Halting the Catastrophic Battle for Sudan’s El Fasher,” 24 June 2024

Al-Baraa Ibn Malik Brigade

While the SAF sought alliances with various rebel groups, it also revived connections with former Islamist allies who had fought in earlier wars during the Bashir regime. The fall of Bashir led to the dismantling of the National Congress Party (NCP)’s ideological and paramilitary arms, such as the PDF and the NISS’s combat units. The Al-Baraa Ibn Malik Brigade, named after a historical fighter in the early Islamic conquest, was initially a part of the PDF that was dissolved in 2020.15Radio Dabanga, “Sudan Armed Forces: ‘Popular Defence Forces dissolved, not absorbed,’” 6 September 2020 However, during the transitional period between 2019 and 2021, the SAF provided civic space for Islamists to reemerge:16Ayin Network, “The Al-Bara Ibn Malik Brigade: a lifeline to the army or a lifelong challenge,” 14 June 2024 Although the military had continuously cracked down on pro-democracy protests, Islamist groups were allowed to hold peaceful protests that opposed the civilian transitional government and the Forces of Freedom and Change (FFC). These opposition groups — which the FFC sidelined — increased their support for the SAF to hinder the process of democratic transition and supported the military coup that ousted the civilian government in October 2021.17Osama Abu Bakr, “Sudan’s Armed Militias and the Crisis of Civil Democratic Transition,” Arab Reform Initiative, 6 July 2023

It was within this context that the al-Baraa Ibn Malik Brigade initially regrouped as an Islamist political group that opposed the civilian government and the Framework Agreement that was signed in December 2022 to restore a power-sharing agreement between civilians and the military.18Munzoul A. M. Assal, “War in Sudan 15 April 2023: Background, analysis, and Scenarios,” International IDEA, August 2023 The group drew its core from former members of paramilitaries that supported Bashir’s ousted NCP regime, such as the PDF and NISS, leveraging personal and institutional ties with SAF commanders to integrate into military ranks once the war began. Since then, the SAF has used the Brigade as both a force multiplier and a political proxy, helping to sustain ties with the NCP and broader Islamist networks. The group is estimated to have recruited around 20,000 fighters,19Mohammed Amin, “Sudan’s biggest self-described ‘jihadi’ group says it will disband once RSF defeated,” Middle East Eye, 12 March 2025 who have been deployed across various infantry divisions, with a notable presence in the Armored Corps bases and front lines in Khartoum, al-Jazirah, and Sennar.

The Sudan Shield Forces and the defection of Abu Aqla Kaikal

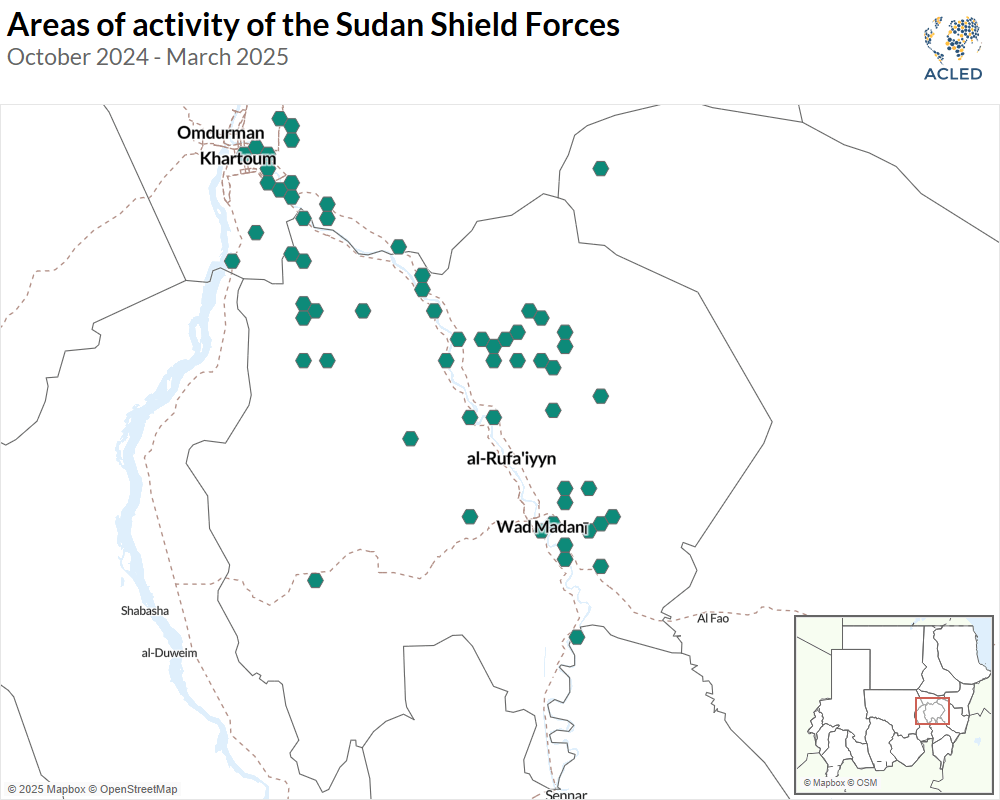

In addition to recruiting and mobilizing allies, the SAF has successfully persuaded some groups that had initially allied with the RSF — often for tactical or opportunistic reasons — to switch sides.20Al Ghad, “Al-Burhan issues a decision to pardon all Rapid Support Forces members who lay down their weapons,” 18 April 2023; Al Jazeera, “Sudan’s army claims first defection of senior RSF commander,” 20 October 2025; Sudan Tribune, “Sudan’s Burhan vows to pursue RSF until defeated,” 14 January 2025 These shifting local alliances have proven to be decisive in shaping the outcomes of battles, particularly following the defection of RSF commander Abu Aqla Kaikal. Kaikal led the Sudan Shield Forces, which was created by military intelligence in 2022 to counterbalance the signatories to the 2020 Juba Peace Agreement between Sudan’s transitional government and some armed groups, and fought alongside the RSF since August 2023.21Sudan Tribune, “Central Sudan’s new armed group of Al-Butana region,” 22 December 2022; ImArabic, “Abu Aqilah Kekel, Commander of Sudan’s Shield Forces, Announces His Joining with His Forces and Equipment to the Rapid Support Forces,” 8 August 2023 Kaikal’s forces played a pivotal role in the RSF’s victories in al-Jazirah and Sennar states. Their deep knowledge of central Sudan and ties with the communities of al-Butanah — an area spanning Khartoum, al-Jazirah, River Nile, and Gedaref states — made them an invaluable RSF asset.

However, after the SAF’s advances in Sennar state, and encouraged by the SAF’s amnesty policy, Kaikal and his forces defected and joined the SAF in October 2024. The Sudan Shield Forces’ departure sent shockwaves through the RSF’s ranks, particularly in central Sudan, where the Sudan Shield Forces had been orchestrating the RSF’s defensive operations to maintain their territorial gains. It also marked the beginning of the RSF’s collapse in the region.

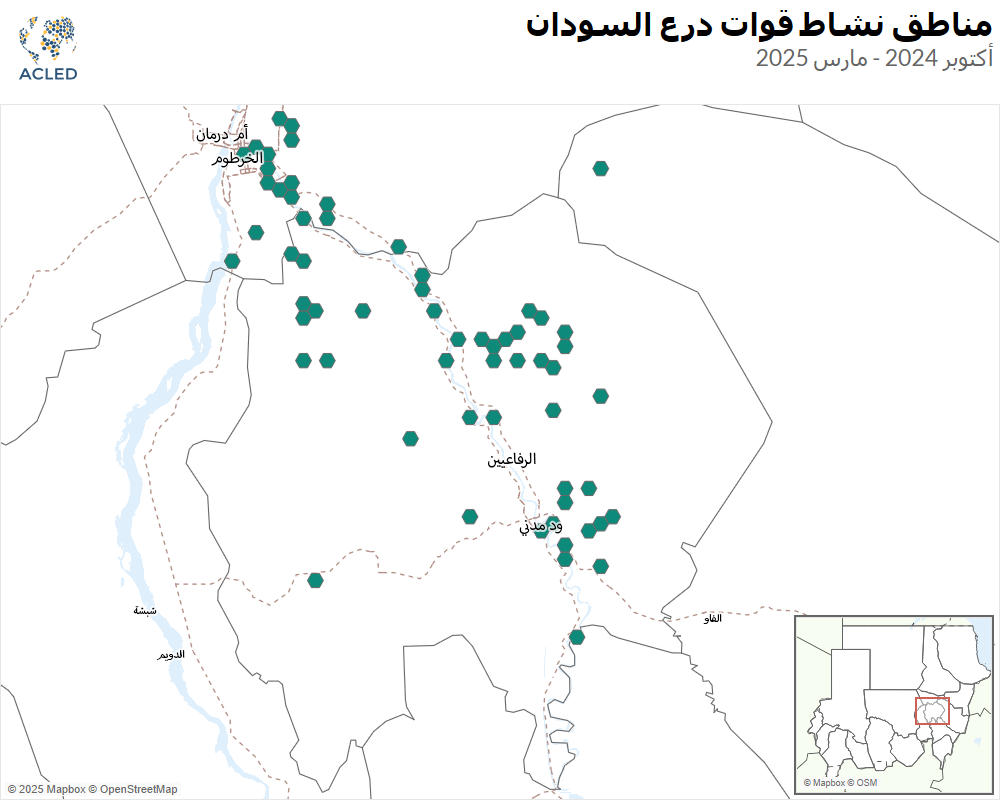

Furious over Kaikal’s betrayal, the RSF launched a brutal retaliatory campaign against his ethnic group, the Shukriya. However, the SAF capitalized on this retaliatory attack, as members of the Shukriya ethnic group joined the SAF under the Sudan Shield Forces.22Samir Ramzy, “‘Tribalization’ of Sudan’s Conflict: Incentives, Restraints and Potential Trajectories,” Emirates Policy Center, 22 November 2025 The SAF struck back hard against the RSF, opening multiple frontlines in east al-Jazirah and Umm al-Qura — where the SAF’s offensive operation in al-Jazirah started. The Sudan Shield Forces’ counteroffensive opened additional frontlines, distracting and overwhelming the RSF, which could not keep up. This paved the way for the SAF’s recapture of al-Jazirah state, a decisive victory that further destabilized the RSF. From al-Jazirah, the SAF and its allies began to mobilize to Khartoum state. The Sudan Shield Forces, in particular, played a major role in pushing the RSF out of Bahri and south Khartoum (see map below).

These carefully cultivated alliances have placed the SAF in a strong position to neutralize the RSF’s allies. By consolidating local rivalries against the RSF and embedding itself into native administration structures, the SAF has ensured that its influence extends beyond the battlefield, shaping the political and social fabric of the region.

The RSF fractures amid internal conflicts

The SAF’s strategic advances and territorial gains in central Sudan coincided with an increase in internecine turmoil within the RSF’s ranks that began in August 2024. Aided by RSF defections in October, the SAF eventually recaptured al-Jazirah, which in turn incited further divisions among the RSF’s ranks in the central region, enabling the SAF offensive on Khartoum. The RSF’s early expansion in Khartoum and al-Jazirah in 2023 was due to its decentralized approach to recruitment and governance, which allowed it to consolidate its control over key logistics and supply routes during the first 18 months of the conflict. But rather than functioning as a unified army with a coherent chain of command, the RSF operated more as a coalition of local militias bound by mutual interests. This loose structure ultimately created a fertile ground for internal competition among ambitious commanders.

The emergence of competing factions by the end of 2024 can be explained by the RSF’s recruitment methods, which relied heavily on ethnic and tribal narratives. Historically, communities in Darfur have a tradition known as “faza’a,” which involves mobilizing fighters through tribal structures.23Julie Flint, “The Other War: Inter-Arab Conflict in Darfur,” Small Arms Survey, 10 October 2010 The RSF used existing communal networks for recruitment by targeting clans and tribes through their community leaders and tribal hierarchies.24Radio Dabanga, “Sudan’s RSF ‘stoke ethnic tensions with tribal recruitment,’” 11 November 2024; Human Rights Watch, “‘The Massalit Will Not Come Home’: Ethnic Cleansing and Crimes Against Humanity in El Geneina, West Darfur, Sudan,” 9 May 2024 The RSF’s early alliance with ethnic militias, such as the Beni Halba, Salamat, Rizeigat, and Misseriya, supported its rapid expansion and enabled it to become the de facto ruling authority in the southern belt of Darfur and Kordofan by the end of 2023. Beyond Darfur, allying with Kaikal in the central region allowed the RSF to control al-Jazirah and Sennar, regions that would otherwise be unfamiliar to the RSF’s core allies in Darfur. This approach resulted in a decentralized, horizontally organized force that fosters high loyalty between lower-ranking soldiers and their direct superiors.25Paul Staniland, “Networks of Rebellion: Explaining Insurgent Cohesion and Collapse,” Cornell University Press, 2014

The RSF’s ethnic/communal-based recruitment strategy resulted in autonomous, mid-level tribal militia commanders who controlled local economies and supply chains and led their own troops in clashes fueled by local agendas.26Tahani Maala, “Beyond the Battlefield: The Survival Politics of the RSF Militia in Sudan,” African Arguments, 14 October 2024 This decentralized structure does not guarantee a coherent chain of command, as was first illustrated by the deadly clashes between RSF-allied Arab groups over land and resources in South and Central Darfur in late 2023, which persisted for months despite mediation attempts by the RSF leadership.27Sudan War Monitor, “Fierce fighting in South Darfur involving RSF-backed Arab militias,” 13 August 2023

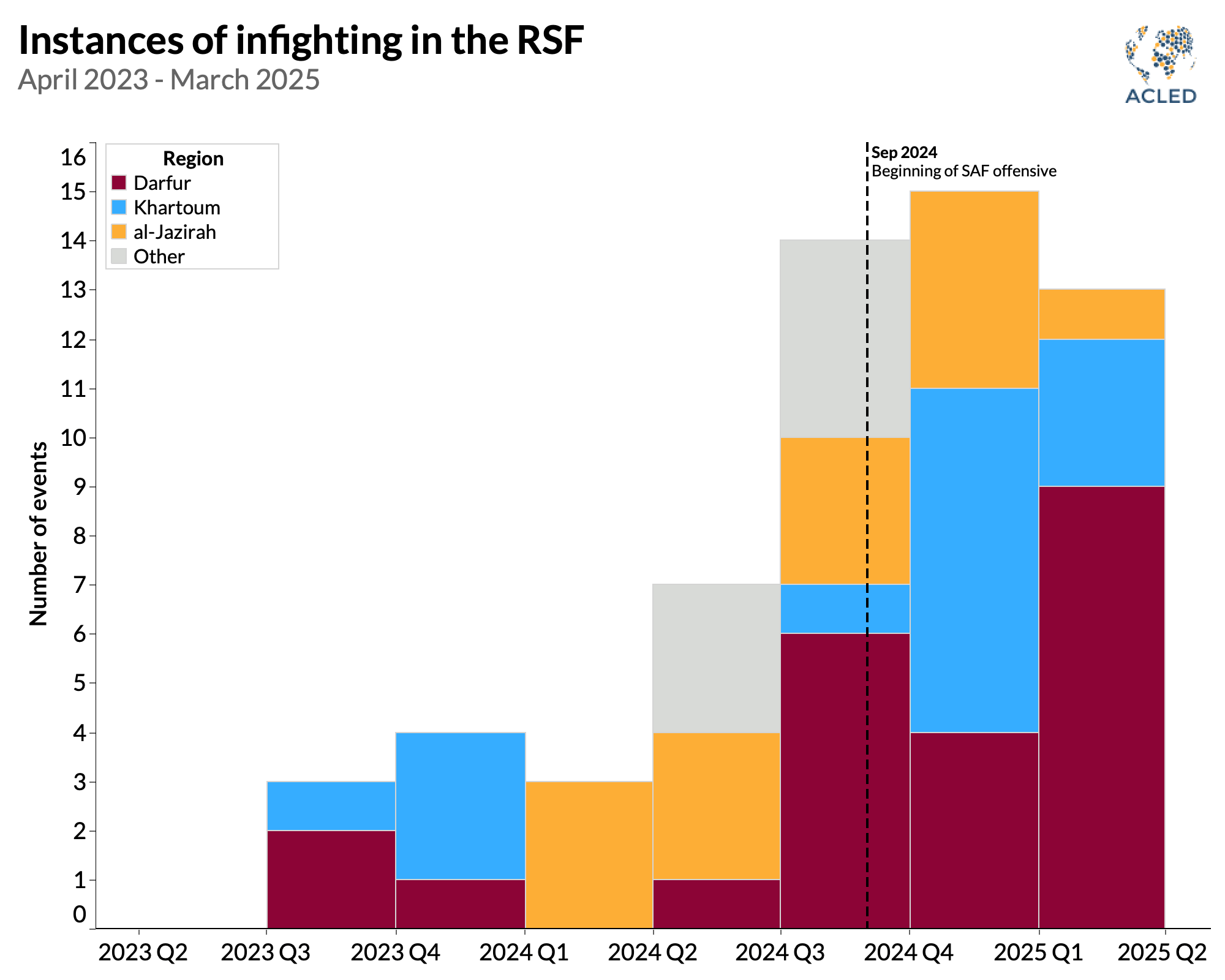

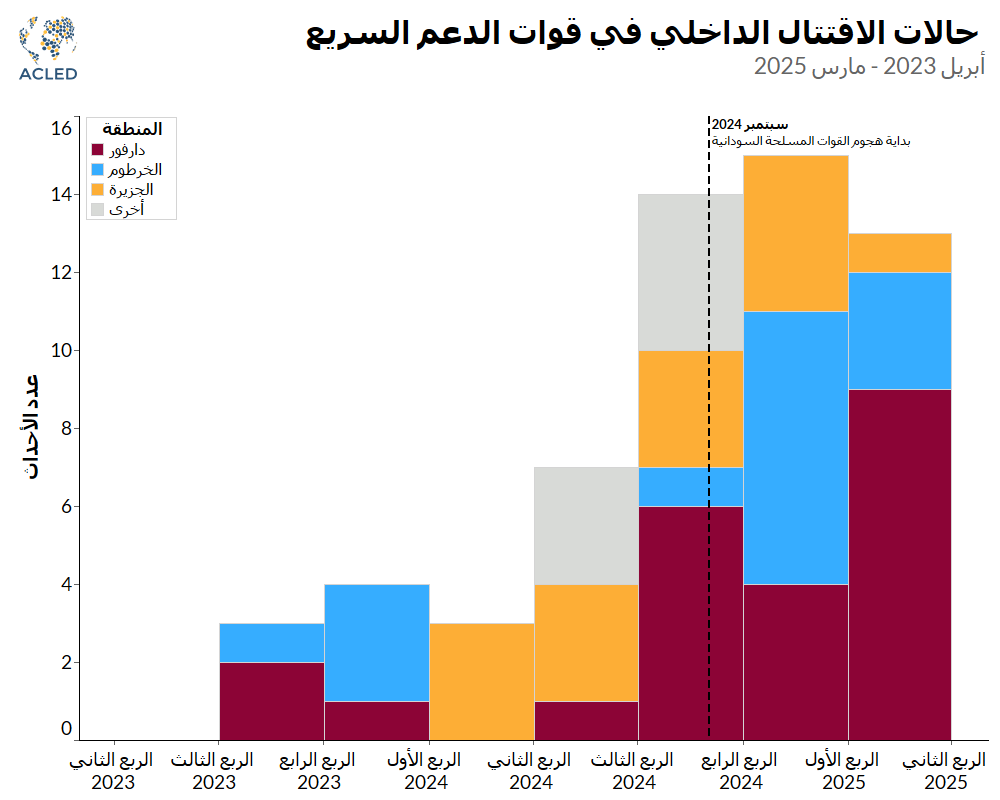

The trend of competition between RSF allies has expanded beyond the Darfur region, and ACLED records many such events in al-Jazirah and Khartoum (see graph below). Internal conflicts often relate to ethnic affiliation or refusal to adhere to top-level commands. On 11 September 2024, for instance, an RSF group consisting of unspecified ethnic groups shot and killed the RSF head of media in Meheiriba, al-Jazirah, after disputing his appointment as commander of that location.

These incidents further eroded morale, culminating in Kaikal’s defection on 20 October 2024 and the subsequent revenge attacks by the RSF on civilians in eastern al-Jazirah. Following his defection, the RSF arrested other members of the RSF and its civil administration who were appointed in Wad Madani in March 2024, accusing them of siding with the defectors. Despite its severe crackdown on civilians, the RSF lost al-Jazirah state two months after Kaikal’s defection, indicating that the event resulted in major losses to the RSF’s troops in the state.

Infighting between RSF-allied militias continued in Khartoum. In December 2024, a group of RSF members from the Misseriya community led by the senior commander Rahmtalla al-Mahdi, better known as “Jalha,” clashed with other RSF members in Soba prison in Khartoum for three consecutive days. The clashes only ended after they destroyed the prison gates and broke out other RSF members who were arrested by the group’s Negative Phenomena Committee, an internal police force that was set up to combat misdemeanors in RSF-controlled regions.28Nafisa Eltahir and Khalid Abdelaziz, “Unruly RSF fighters sow chaos in Sudan’s farming heartland,” Reuters, 9 August 2024 Jalha — who was killed on 28 January 2025 — was a militia leader who fought in Libya and returned to join the RSF in September 2023.29Sudan Tribune, “RSF commander ‘Jalha’ killed under unclear circumstances,” 28 January 2025 Despite attempts by the RSF leadership to control its forces, allied militias still operate semi-independently, many of them under the command of mercenaries or local warlords who prioritize quick economic gains.

Although the RSF spread to many regions in Sudan, it failed to establish a reliable form of governance beyond localized taxation systems, permits, and checkpoints, which also played a role in the RSF’s fracturing in the central region. Despite having appointed its own civil administrations, the RSF was unable to maintain secure environments for residents within its territories. Over 68% of violence targeting civilians recorded by ACLED since the conflict began was committed by the RSF, indicating a higher tolerance for criminal activity in areas under its control.30New York Times, “How ‘Trophy’ Videos Link Paramilitary Commanders to War Crimes in Sudan,” 31 December 2024 Allowing its members autonomy in operating markets and taxation strategies enabled the RSF to dominate local economies and key access routes, isolating SAF-controlled regions and facilitating forced conscription and cooperation from local residents and informants.

However, this approach fostered a culture of pillaging and prioritizing wartime spoils among RSF-allied militias, ultimately exacerbating competition between RSF units and leading some factions to rebel against commands to secure economic gains. For instance, on 14 September 2024, RSF militias led by Ismail Hussein and Bashir Balnja clashed in Umm Rawaba, North Kordofan, over a dispute regarding looted cows, resulting in 13 fatalities. Five days later, further clashes occurred when a group of RSF fighters resisted an order banning motorbikes, vehicles commonly used by militias in civilian looting.

Moreover, the SAF’s advances in early 2025 significantly weakened the RSF’s remaining positions in central Sudan. The SAF’s control of al-Jazirah state was particularly impactful, as it strategically links several states and provides valuable economic advantages previously leveraged by the RSF through control over agricultural production and food supplies.31Tamer Abd Elkreem and Susanne Jaspars, “Sudan’s catastrophe: the role of changing dynamics of food and power in the Gezira agricultural scheme,” 30 October 2024 The subsequent SAF advances in Khartoum and North Kordofan in February 2025 further strained the RSF, limiting its operations and logistics network and leading to its loss of the majority of Khartoum by March 2025.

Alliances remain critical to the SAF’s push south and west

As the SAF recaptures the majority of Khartoum state and seeks support for reconstruction, the conflict will likely shift westward and southward.32International Crisis Group, “Two Years On, Sudan’s War is Spreading,” 7 April 2025 In Khartoum, the SAF has successfully pushed the RSF to retreat west toward southern Omdurman — its only remaining stronghold in the tri-city capital area — which links Khartoum with North Kordofan and White Nile states. Though the RSF still surrounds El Obeid from the west, the SAF partially lifted the siege on the city and connected it with the SAF-controlled southeastern region, indicating it will be used to bolster future SAF offensives in the western region.33Basillioh Rukanga, “Sudan army ends two-year siege of key city,” BBC News, 24 February 2025 To limit the SAF offensive in the west, the RSF started shelling the North Kordofan capital on 7 March and mobilized its forces to attack the SAF-controlled al-Nuhud in West Kordofan.

As the SAF’s offensive operation moves west to the RSF’s stronghold in Darfur, the RSF is escalating its efforts to capture El Fasher, the capital of North Darfur and the last state capital outside of the RSF’s control in Darfur. The RSF’s capture of the strategic town of al-Malha — located on the road linking North Darfur to the SAF-controlled Northern state — on 20 March demonstrates the group’s plan to disrupt the SAF’s reinforcements to El Fasher and to weaken the Darfur Joint Forces.34Sudan War Monitor, “RSF captures strategic desert city in North Darfur,” 20 March 2025 For both belligerents, alliances with local armed groups and foreign powers are critical to gaining the upper hand in the battle for Darfur. The SAF’s established alliances in Darfur facilitate mobilization for the SAF among non-Arab and Arab communities, disrupting the RSF’s network in the region. On the other hand, the RSF’s access to fighters from the region and neighboring countries like Libya, Chad, and South Sudan, alongside advanced military equipment, including drones, will make the battle for Darfur and the defeat of the RSF in its stronghold more challenging for the SAF and its allies.

In the south, the RSF’s recent alliance with the SPLM-N led by Abdelaziz al-Hilu extended a critical lifeline, enabling the RSF’s troops to regroup in SPLM-N-controlled areas in South Kordofan and Blue Nile states. This alliance facilitated access to resources smuggled through SPLM-N networks along the southern border with South Sudan.35Mat Nashed, “Is Sudan’s war merging with South Sudanese conflicts?” Al Jazeera, 29 March 2025 For the first time since the beginning of the conflict, on 27 March, there was a drone attack on al-Damazin, the capital of the Blue Nile state, indicating a shift in the RSF’s offensives to the south, aided by its new alliance.36Genocide Watch, “Sudan army takes control of Khartoum, RSF holds Darfur,” 30 March 2025 Across the southern border, the RSF clashed with the South Sudanese opposition groups in Renk town on 15 March, seemingly aligning itself with the South Sudanese government.37Sudan Post, “SPLA-IO generals killed in clashes with RSF in Renk County village,” 17 March 2025 The SAF generals have since threatened military action against Chad and South Sudan, accusing the neighboring countries of supporting the RSF.38Reuters, “South Sudan and Chad condemn Sudanese general’s threats to attack them,” 24 March 2025

The unlikelihood of a realistic de-escalation or ceasefire and the SAF’s increasing threats to Chad and South Sudan highlight the risk of a war that, far from subsiding, could escalate, wreaking ever more destruction to its population and pulling neighboring countries in. Both belligerents are acquiring advanced military equipment through external actors, further fueling the escalation of violence in several regions.39Human Rights Watch, “Sudan: Abusive Warring Parties Acquire New Weapons,” 9 September 2024 As the conflict drags on, the future of the war in Sudan will be determined by the warring parties’ ability to maintain their alliances, mitigate fragmentation, and effectively manage allies and their competing agendas.

Visuals produced by Christian Jaffe

عامان من الحرب في السودان: كيف تكتسب القوات المسلحة السودانية اليد العليا

بعد 23 شهرًا من الحرب، في 21 مارس، استعادت القوات المسلحة السودانية وحلفاؤها السيطرة على القصر الرئاسي في وسط الخرطوم، بالإضافة إلى جميع الوزارات والمباني الحكومية المحيطة به. بينما انسحبت قوات الدعم السريع من مدينة الخرطوم – وهي خطوة وصفتها المجموعة بأنها استراتيجية – أعلنت القوات المسلحة السودانية السيطرة الكاملة على عاصمة السودان المكونة من ثلاث مدن في 26 مارس. ([1]) وبالتالي، يمثل استعادة مدينة الخرطوم لحظة فاصلة في الصراع: فقد اكتسبت القوات المسلحة السودانية الآن اليد العليا، خاصة في وسط السودان. على الرغم من أن سقوط الخرطوم قد يبدو وكأنه حدث بسرعة للمراقبين العاديين، إلا أنه يمثل تتويجًا لهجوم بدأ في نهاية سبتمبر 2024 بهجمات منسقة على مواقع تابعة لقوات الدعم السريع في المدن الثلاث لولاية الخرطوم – بحري وأم درمان والخرطوم.

كما استعادت القوات المسلحة السودانية عاصمتي ولايتي سنار والجزيرة، مما أجبر قوات الدعم السريع على اتخاذ موقف دفاعي متزايد في الخرطوم. أدت حملة القوات المسلحة السودانية في نهاية المطاف إلى إخراج قوات الدعم السريع من وسط السودان، وكسر حصارها على العديد من قواعد القوات المسلحة السودانية في ولايات الخرطوم وسنار وشمال كردفان، وقطع طرق الإمداد الحيوية، مما أدى إلى محاصرة قوات الدعم السريع من قبل القوات المسلحة السودانية في وسط الخرطوم. إجمالاً، منذ بدء الهجوم، استعادت القوات المسلحة السودانية وحلفاؤها أكثر من 430 موقعًا في مختلف أنحاء وسط وجنوب السودان (انظر الخريطة أدناه).

بينما سهّل التدخل الأجنبي تقدم القوات المسلحة السودانية [2]، لعبت ثلاثة تحولات مهمة داخل المعسكرات المتحاربة في السودان دورًا حاسمًا في تغيير مسار الحرب: تعزيز القوات المسلحة السودانية لعمليات التجنيد لمعالجة النقص المزمن في القوة البشرية، وظهور تحالفات جديدة بين الجماعات المسلحة، وتفكك قوات الدعم السريع. بينما لا تزال بعض مناطق ولاية الخرطوم متنازع عليها، وخاصة في غرب وجنوب أم درمان، تدخل الحرب في السودان مرحلة جديدة.

من الدفاع إلى الهجوم: التقدمات العسكرية للقوات المسلحة السودانية

عندما شنت القوات المسلحة السودانية عمليتها الهجومية في 26 سبتمبر، تحرك الجنود في كل قاعدة بالخرطوم نحو مواقع قوات الدعم السريع في لمدن الثلاث لولاية الخرطوم (انظر الخريطة أدناه). بدعم من الغطاء الجوي ونيران المدفعية، تقدم مشاة القوات المسلحة السودانية شرقًا لإخراج قوات الدعم السريع من الخرطوم. ركزت استراتيجية القوات المسلحة السودانية لاستعادة الخرطوم على ثلاث مناورات: ربط القوات المحاصرة في الخرطوم وسنار وكردفان؛ وقطع خطوط إمداد قوات الدعم السريع؛ وتطويق قوات الدعم السريع في وسط الخرطوم من خلال التعبئة من ولايتي النيل الأبيض والجزيرة المجاورتين.

عندما اندلع الصراع في 15 أبريل 2023، حاصرت قوات الدعم السريع معظم قواعد القوات المسلحة السودانية في الخرطوم. مما قيد القوات المسلحة السودانية من استخدام كامل قدرة قواعدها لمحاربة قوات الدعم السريع. كانت الاستراتيجية الأولى للقوات المسلحة السودانية هي إنهاء الحصار على قواعدها في الخرطوم. وبناءً على ذلك، في 28 سبتمبر، وهو اليوم الثالث من العملية الهجومية في الخرطوم، كسرت القوات المسلحة السودانية الحصار على قاعدتي سلاح الأسلحة وسلاح الاستطلاع في شمال بحري. بعد رفع الحصار عن هاتين القاعدتين، انضمت القوات إلى وحدات أخرى من القوات المسلحة السودانية في القتال لطرد قوات الدعم السريع من الخرطوم والولايات المجاورة. إن عملية كسر هذه الحصارات استغرقت عدة أشهر لإنجازها، وتم أخيرًا كسر حصار قوات الدعم السريع على مقر القيادة العامة ([3]) في قلب الخرطوم في 24 يناير الذي استمر 21 شهرًا. وقد أدى هذا إلى تحرير العديد من وحدات القوات المسلحة السودانية وتمركزها للقتال في وسط الخرطوم.

خارج الخرطوم، قامت القوات المسلحة السودانية بتركيز مماثل بنشر قواتها في ولايتي سنار والجزيرة. في 5 أكتوبر، ربطت القوات المسلحة السودانية قواتها في مدينة سنار بتلك الموجودة في ولاية النيل الأبيض، وفي 23 نوفمبر، كسرت القوات المسلحة السودانية وحلفاؤها الحصار على العاصمة سنجة (انظر الخريطة أدناه). بحلول بداية عام 2025، سقط معظم ولاية سنار في يد القوات المسلحة السودانية. وبحلول نهاية مارس، أعلنت القوات المسلحة السودانية أيضًا سيطرتها الكاملة على ولاية الجزيرة. إلى جانب إطلاق كل قاعدة لعملية هجومية، بدأت القوات المسلحة السودانية وحلفاؤها في التقدم نحو الخرطوم من ولايتي الجزيرة والنيل الأبيض المجاورتين، مما أدى إلى تطويق قوات الدعم السريع في وسط الخرطوم بشكل فعال. لجأت القوات المسلحة السودانية إلى استخدام ضربات الطائرات المسيرة والصواريخ التي تستهدف أي تعزيزات لقوات الدعم السريع في وسط الخرطوم.

توسعت العمليات الهجومية للقوات المسلحة السودانية لتشمل كردفان في أواخر يناير، بهدف تعطيل خطوط الإمداد العسكرية لقوات الدعم السريع، مثل القوات، من دارفور إلى وسط وجنوب السودان (انظر الخريطة أدناه). في 23 فبراير، كسرت القوات المسلحة السودانية جزئيًا الحصار على مدينة الأبيض ,عاصمة شمال كردفان، والتي تُعتبر مقرًا لقيادة الفرقة الخامسة مشاة. وفي اليوم التالي، كسرت القوات المسلحة السودانية أيضًا جزئيًا الحصار على مدينة الدلنج في جنوب كردفان من الجنوب وتمكنت من ربط اللواء 54 مشاة التابع لها بقواتها في العاصمة، مدينة كادقلي. منذ يونيو 2023، حاصرت قوات الدعم السريع المدينة من الشرق والشمال، بينما قام فصيل عبد العزيز الحلو من الحركة الشعبية لتحرير السودان – شمال بحصارها من الغرب والجنوب.

لقد أثبتت استراتيجية القوات المسلحة السودانية ذات المحاور الثلاثة فعاليتها إلى حد كبير. لا تزال قوات الدعم السريع تسيطر على أجزاء من غرب وجنوب أم درمان، لكن القوات المسلحة السودانية وحلفاؤها سيطروا بشكل كامل على بحري في 3 مارس ومدينة الخرطوم في 26 مارس. وعلى الرغم من أن القوات المسلحة السودانية لم تتمكن حتى الآن من انتزاع الجانب الغربي للأبيض من قوات الدعم السريع، فإن كسر الحصار الجزئي للمدينة يمثل علامة فارقة مهمة نظرًا لموقعها الاستراتيجي الذي يربط ولايتي كردفان ودارفور – معقل قوات الدعم السريع – بالخرطوم والولايات الوسطى الأخرى.

واصلت القوات المسلحة السودانية غاراتها الجوية على غرب البلاد، مستهدفة مواقع قوات الدعم السريع في جميع ولايات دارفور. في مارس، استهدفت القوات المسلحة السودانية مناطق في دارفور يُعتقد أن قوات الدعم السريع وحلفاؤها كانوا يعقدون اجتماعات فيها. منذ 22 فبراير، تقوم قوات الدعم السريع وحلفاؤها بوضع الأسس لإنشاء حكومة موازية في المناطق التي تسيطر عليها قوات الدعم السريع، وذلك لانتزاع الشرعية الدبلوماسية من الحكومة التي تقودها القوات المسلحة السودانية، والتي تتخذ حاليًا من ولاية البحر الأحمر مقرًا لها. ([4]) و لتعطيل هذه العملية، استهدفت القوات المسلحة السودانية مواقع مختلفة. ففي نيالا، عاصمة جنوب دارفور، استهدفت القوات المسلحة السودانية مطار نيالا في 13 و14 مارس. زعمت القوات المسلحة السودانية أنها قتلت عددًا غير محدد من قوات الدعم السريع. وفي اليوم التالي، في 15 مارس، استهدفت غارات جوية بطائرات مسيرة تابعة للقوات المسلحة السودانية فندقًا في نيالا، مما أدى إلى إصابة 10 سياسيين متحالفين مع قوات الدعم السريع. وبالمثل، استهدفت غارات جوية تابعة للقوات المسلحة السودانية مقر حكومة شرق دارفور في الضعين، شرق دارفور. لم يكن هناك ضحايا. أشارت التقارير إلى أن مدينتي الضعين ونيالا استضافتا اجتماعات بين قوات الدعم السريع وحلفائها لمناقشة تشكيل حكومة موازية في المناطق التي تسيطر عليها قوات الدعم السريع. ([5])

القوات المسلحة السودانية تعزز قوتها البشرية من خلال التجنيد

منذ بداية الحرب، أعطت القوات المسلحة السودانية الأولوية لإبقاء التكلفة البشرية في الحد الأدنى، مدركة أن جنودها يمثلون عنصرا أساسيًا يصعب إعادة بنائه بمجرد فقده. وبدلاً من ذلك، أعطت الأولوية لاستخدام العنف عن بعد، مثل الضربات الجوية وضربات الطائرات المسيرة، لإلحاق أقصى قدر من الضرر بقوات الدعم السريع دون تكبد خسائر كبيرة في صفوفها. نظرًا لتفوق قوات الدعم السريع عددياً، كانت تكتيكات القوات المسلحة السودانية القتالية دفاعية إلى حد كبير وهدفت إلى استنزاف موارد قوات الدعم السريع وإلحاق خسائر فادحة بها. استغلت هذه الاستراتيجية تكتيكات “مفرمة اللحم” التي تعتمد عليها قوات الدعم السريع، والتي تعتمد بشكل كبير على الهجمات الأمامية الواسعة وكثافة القوات التي جعلتها عرضة لخسائر كبيرة.

ومع ذلك، شكلت القوة البشرية المحدودة للقوات المسلحة السودانية تحديًا خطيرًا، حيث كانت قوات الدعم السريع تشكل جزءًا كبيرًا من قوات المشاة التابعة للقوات المسلحة السودانية قبل بداية الحرب. و لمعالجة هذا الضعف، لجأت القوات المسلحة السودانية إلى تجنيد القوات، بما في ذلك عن طريق تقديم عفو عام عن المنشقين عن قوات الدعم السريع الذين انضموا إلى القوات المسلحة السودانية. كما عززت قواتها بسحب كتائب صغيرة وتجميعها داخل قواعد عسكرية رئيسية لتعزيز المواقع الاستراتيجية. شملت هذه الخطوة، بشكل مثير للجدل، سحب فرقتين مشاة رئيسيتين من مدينتي ود مدني وسنجة.

كان سقوط ود مدني، عاصمة ولاية الجزيرة، في يد قوات الدعم السريع في ديسمبر 2023 نقطة تحول. وقد أشار ذلك إلى قدرة القوات المسلحة السودانية المحدودة على احتواء قوات الدعم السريع، لأنه في غضون شهرين، سقطت خمس ولايات – وسط دارفور وشرق دارفور وجنوب دارفور وغرب دارفور والجزيرة – في يد قوات الدعم السريع. كان بإمكان القوات المسلحة السودانية الاحتفاظ بالسيطرة على ود مدني لكنها انسحبت دون تقديم تفسير – تاركة المدينة والمنطقة المحيطة بها لقوات الدعم السريع. ([6]) اتُهمت قوات الدعم السريع بنهب وقتل واغتصاب السكان والمواطنين النازحين. ([7]) وفقًا للأمم المتحدة، نزح أكثر من 500 ألف شخص من ود مدني والمناطق المحيطة بها في أعقاب سيطرة قوات الدعم السريع. ([8])

أدى ذلك إلى انتقادات للقوات المسلحة السودانية لفشلها في حماية المدينة وأثار الذعر في جميع الولايات المتبقية التي تسيطر عليها القوات المسلحة السودانية. نتيجة لذلك، بدأت الميليشيات العرقية والمجتمعية في حشد جماعي ضد قوات الدعم السريع، مما يعكس فقدان الثقة في قدرة القوات المسلحة السودانية على الدفاع عن المجتمعات.

في الوقت نفسه، دعا عبد الفتاح البرهان، قائد القوات المسلحة السودانية، إلى التعبئة العامة ضد قوات الدعم السريع في يناير 2024. ([9]) استجاب آلاف المتطوعين، إلى جانب الزعماء التقليديين وأعضاء الإدارات الأهلية، لنداء القوات المسلحة السودانية لحمل السلاح. ([10]) بعد دعوة البرهان، أُنشئت معسكرات تدريب في جميع أنحاء شمال وشرق السودان.([11]) هنا، تم تدريب المجندين ليتم نشرهم في الخطوط الأمامية لولاية الخرطوم ومنطقة دارفور وولاية الجزيرة.

لعبت القوة المشتركة لحركات الكفاح المسلح – مسار دارفور، المعروفة اختصارًا بـ “قوات دارفور المشتركة”، – وهي تحالف من جماعات متمردة سابقة مقرها دارفور والتي وقعت اتفاقية جوبا للسلام مع الحكومة الانتقالية في عام 2020 – دورًا رئيسيًا في وسط السودان ودارفور. عندما اندلعت معركة الفاشر، عاصمة ولاية شمال دارفور، في أبريل 2024، وجدت الفرقة السادسة مشاة التابعة للقوات المسلحة السودانية حليفًا استراتيجيًا في قوات دارفور المشتركة. تحت لوائها، حشدت الإدارة الأهلية للزغاوة قوات، وأعلنت الحرب على قوات الدعم السريع، وحددت موعدًا نهائيًا لأفراد الزغاوة الآخرين في قوات الدعم السريع لطلب العفو. أدت حملة التعبئة إلى توسيع نطاق التجنيد، حيث سمحت للقوات المسلحة السودانية من إسناد الأعباء الإدارية للتدريب والتجنيد الإضافي إلى حلفائها، مما أدى إلى زيادة كبيرة في قوتها البشرية من خلال دمج مقاتلين ذوي معرفة جغرافية محلية عميقة.

علاوة على ذلك، بعد أن فتحت القوات المسلحة السودانية معسكرات تدريب لقوات دارفور المشتركة في ولايتي كسالا والقضارف في شرق السودان،([12]) انضم مجندون إلى القتال مع الجيش لاستعادة السيطرة على وسط السودان. تم نشر مجموعات مختلفة من قوات دارفور المشتركة في الخطوط الأمامية في ولايتي سنار والقضارف والتي انطلقت منها إلى ولاية الجزيرة. كانت هذه الإستراتيجية أحد الأسباب التي مكّنت القوات المسلحة السودانية من التغلب على قوات الدعم السريع.

استيعاب المنشقين عن قوات الدعم السريع وتكوين تحالفات

كان العامل الرئيسي الثاني الذي مكّن تقدم القوات المسلحة السودانية هو جهد بناء تحالفات يهدف إلى حشد الدعم بين الجماعات المسلحة الأخرى. بالاعتماد على استخباراتها العسكرية وخبرتها الواسعة في مكافحة التمرد، تمكنت القوات المسلحة السودانية من تأجيج الخصومات المحلية لصالحها وحشد المعارضة لقوات الدعم السريع في جميع أنحاء السودان.

سعت القوات المسلحة السودانية إلى إقامة تحالفات من خلال جذب الجماعات المسلحة المحايدة أو دعم الجماعات شبه العسكرية المتحالفة مع قوات الدعم السريع أو نظام الرئيس السابق عمر البشير لأسباب تكتيكية وانتهاز الفرص. وبذلك، هدفت إلى تعزيز سيطرتها غير المباشرة على الأراضي، وتقوية وجودها المحلي، وضمان دعم أوسع لأهدافها العسكرية والسياسية. من بين هذه الجماعات قوات دارفور المشتركة وقوات درع السودان. كما أعادت القوات المسلحة السودانية إحياء قوات شبه عسكرية تابعة لها تم حلها سابقًا – مثل قوات الدفاع الشعبي، و كتيبة البراء بن مالك، ووحدات القتال التابعة لجهاز الأمن والمخابرات الوطني (انظر الصورة أدناه). قدم كل من هؤلاء الحلفاء للقوات المسلحة السودانية خبرات ومزايا جغرافية فريدة.

قوات دارفور المشتركة

قوات دارفور المشتركة هي تحالف من خمس جماعات متمردة سابقة – وهي حركة/جيش تحرير السودان بقيادة مني مناوي، وحركة العدل والمساواة بقيادة جبريل إبراهيم، والتحالف السوداني، وحركة/جيش تحرير السودان – المجلس الانتقالي، وتجمع قوى تحرير السودان – التي كانت نشطة في دارفور بين عامي 2003 و 2020 وتم تعيينها في الحكومة الانتقالية نتيجة لاتفاقية جوبا للسلام في عام 2020. أعلن أربعة أعضاء في التحالف – حركة العدل والمساواة بقيادة جبريل إبراهيم، وفصيل حركة/جيش تحرير السودان بقيادة مني مناوي، وفصيل حركة/جيش تحرير السودان بقيادة مصطفى طمبور، وفصيل من تجمع قوى تحرير السودان – عن دعمهم للقوات المسلحة السودانية في نوفمبر 2023. جاء ذلك عقب الاشتباكات العرقية الشديدة التي وقعت في غرب دارفور في يونيو 2023 واستيلاء قوات الدعم السريع على أربع من أصل خمس ولايات دارفور في أكتوبر ونوفمبر 2023 وحشدها للسيطرة على الفاشر، العاصمة الدارفورية الوحيدة التي لا تزال في أيدي القوات المسلحة السودانية وحلفائها (انظر الجدول الزمني أدناه).

تطورات رئيسية تتعلق بقوات دارفور المشتركة

أبريل 2023 | جماعات متمردة سابقة تؤسس قوات دارفور المشتركة كهيئة محايدة لحماية المدنيين في دارفور

يونيو 2023 | قوات الدعم السريع تقتل والي غرب دارفور وتهاجم مدنيين من المساليت في غرب دارفور

أكتوبر 2023 | قوات الدعم السريع تستولي على نيالا، عاصمة جنوب دارفور

أكتوبر 2023 | قوات الدعم السريع تسيطر على زالنجي، عاصمة وسط دارفور

نوفمبر 2023 | قوات الدعم السريع تستولي على الجنينة، عاصمة غرب دارفور، وتهاجم مدنيين من المساليت

نوفمبر 2023 | أربعة أعضاء في قوات دارفور المشتركة يتخلون عن الحياد ويعلنون دعمهم للقوات المسلحة السودانية

نوفمبر 2023 | قوات الدعم السريع تسيطر على الضعين، عاصمة شرق دارفور

مارس 2024 | انفصل فصيل حركة/جيش تحرير السودان – المجلس الانتقالي وفصيل تجمع قوى تحرير السودان بقيادة الطاهر حجر عن قوات دارفور المشتركة، وأعلنا حيادهما

أبريل 2024 | حركة/جيش تحرير السودان – المجلس الانتقالي تنسحب من مواقعها في الفاشر وتشتبك مع قوات دارفور المشتركة

فبراير 2025 | تجمع قوى تحرير السودان وحركة/جيش تحرير السودان – المجلس الانتقالي ينحازان إلى قوات الدعم السريع

في فبراير 2024، بدأت القوات المسلحة السودانية تدريب المقاتلين المجندين من كل جماعة مسلحة داخل قوات دارفور المشتركة في شرق السودان. بعد تخرج الآلاف، تم نشرهم للقتال مع القوات المسلحة السودانية في المناطق الوسطى من البلاد، بما في ذلك ولايات الخرطوم وسنار والجزيرة والنيل الأبيض.([13]) مكنت خبرة قوات دارفور المشتركة في حرب العصابات في المناطق الريفية وجغرافيا الصحراء من دعم القوات المسلحة السودانية في شن مناورات هجومية ضد قوات الدعم السريع في مواقع متعددة. وشمل ذلك شن معارك “لتحرير” مصفاة الجيلي النفطية في ريف الخرطوم من قوات الدعم السريع. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، لعبت قوات دارفور المشتركة دورًا في القتال للسيطرة على سوق أم درمان، مما سمح للقوات المسلحة السودانية بربط قواتها في شمال وجنوب أم درمان داخل الخرطوم وساهم في تقدم القوات المسلحة السودانية في استعادة السيطرة على ولاية الجزيرة ومنطقة الفاو في ولاية القضارف وجبهات قتال رئيسية أخرى في ولاية سنار.

لم يكن من الممكن تحقيق تقدم القوات المسلحة السودانية في المناطق الوسطى والجنوبية لولا انشغال قوات الدعم السريع بمعارك في شمال دارفور. بدون الفاشر – آخر معقل متبقٍ لدارفور تحت سيطرة القوات المسلحة السودانية – يتضاءل النفوذ الاستراتيجي لقوات الدعم السريع على منطقة دارفور بأكملها. لذلك، قاتلت قوات الدعم السريع بإصرار للاستيلاء على المدينة، وحافظت على حصارها لما يقرب من عام وشنت هجمات متواصلة. لعبت قوات دارفور المشتركة دورًا حاسمًا في تمكين القوات المسلحة السودانية من الحفاظ على الفاشر، حيث شنت مناورات مختلفة لتعطيل طرق إمداد قوات الدعم السريع. ألحقت هذه العمليات خسائر كبيرة بقوات الدعم السريع، مما أجبرها على نشر آلاف الجنود لتعزيز خطوطها الأمامية في الفاشر، الأمر الذي أضعف قدرتها على الحفاظ على السيطرة في جبهات قتال أخرى.([14])

كتيبة البراء بن مالك

بينما سعت القوات المسلحة السودانية إلى إقامة تحالفات مع مختلف الجماعات المتمردة، فقد أحيت أيضًا علاقاتها مع حلفاء إسلاميين سابقين قاتلوا في حروب سابقة خلال نظام البشير. أدى سقوط البشير إلى تفكيك الأذرع الأيديولوجية وشبه العسكرية لحزب المؤتمر الوطني، مثل قوات الدفاع الشعبي ووحدات القتال التابعة لجهاز الأمن والمخابرات الوطني. كانت كتيبة البراء بن مالك، التي سميت على اسم مقاتل تاريخي في الفتوحات الإسلامية الأولى، في الأصل جزءًا من قوات الدفاع الشعبي التي تم حلها في عام 2020.([15]) ومع ذلك، خلال الفترة الانتقالية بين عامي 2019 و 2021، وفرت القوات المسلحة السودانية مساحة مدنية للإسلاميين للظهور مجددًا:([16]) فعلى الرغم من أن الجيش قمع باستمرار الاحتجاجات المؤيدة للديمقراطية، سُمح للجماعات الإسلامية بتنظيم احتجاجات سلمية عارضت الحكومة الانتقالية المدنية وقوى الحرية والتغيير. زادت جماعات المعارضة هذه – التي همشتها قوى الحرية والتغيير – من دعمها للقوات المسلحة السودانية لعرقلة عملية الانتقال الديمقراطي وأيدت الانقلاب العسكري الذي أطاح بالحكومة المدنية في أكتوبر 2021.([17])

في هذا السياق، أعادت كتيبة البراء بن مالك تجميع صفوفها في البداية كجماعة سياسية إسلامية عارضت الحكومة المدنية والاتفاق السياسي الذي تم توقيعه في ديسمبر 2022 لاستعادة اتفاق تقاسم السلطة بين المدنيين والجيش.([18]) استمدت المجموعة قاعدتها الأساسية من أعضاء سابقين في قوات شبه عسكرية دعمت نظام حزب المؤتمر الوطني المخلوع بزعامة البشير، مثل قوات الدفاع الشعبي وجهاز الأمن والمخابرات الوطني، مستفيدة من الروابط الشخصية والمؤسساتية مع قادة القوات المسلحة السودانية للاندماج في صفوف الجيش بمجرد بدء الحرب. منذ ذلك الحين، استخدمت القوات المسلحة السودانية الكتيبة كقوة مضاعفة ووكيل سياسي على حد سواء، مما ساعد في الحفاظ على العلاقات مع حزب المؤتمر الوطني وشبكات إسلامية أوسع. يُقدر بأن المجموعة جندت حوالي 20 ألف مقاتل،([19]) تم نشرهم في مختلف فرق المشاة، مع وجود ملحوظ في قواعد سلاح المدرعات والخطوط الأمامية في الخرطوم والجزيرة وسنار.

قوات درع السودان وانشقاق أبو عاقلة كيكل

بالإضافة إلى تجنيد وحشد الحلفاء، فقد نجحت القوات المسلحة السودانية في إقناع بعض الجماعات التي تحالفت في البداية مع قوات الدعم السريع – غالبًا لأسباب تكتيكية أو انتهاز للفرص – بتغيير ولاءاتها.([20]) أثبتت هذه التحالفات المحلية المتغيرة بأنها حاسمة في تشكيل نتائج المعارك، خاصة بعد انشقاق قائد قوات الدعم السريع أبو عاقلة كيكل. قاد كيكل قوات درع السودان، التي أنشأتها الاستخبارات العسكرية في عام 2022 لموازنة الموقعين على اتفاقية جوبا للسلام لعام 2020 بين الحكومة الانتقالية السودانية وبعض الجماعات المسلحة، وقاتل إلى جانب قوات الدعم السريع منذ أغسطس 2023.([21]) لعبت قوات كيكل دورًا محوريًا في انتصارات قوات الدعم السريع في ولايتي الجزيرة وسنار. معرفتهم العميقة بوسط السودان وعلاقاتهم بمجتمعات البطانة – وهي منطقة تمتد عبر ولايات الخرطوم والجزيرة ونهر النيل والقضارف – جعلتهم أصلا لا يقدر بثمن لقوات الدعم السريع.

ومع ذلك، وبعد تقدم القوات المسلحة السودانية في ولاية سنار، ومتشجعًا بسياسة العفو التي أعلنتها القوات المسلحة السودانية، انشق كيكل وقواته وانضموا إلى القوات المسلحة السودانية في أكتوبر 2024. أحدث رحيل قوات درع السودان صدمة في صفوف قوات الدعم السريع، خاصة في وسط السودان، حيث كانت قوات درع السودان تدير عمليات قوات الدعم السريع الدفاعية للحفاظ على مكاسبها في الأراضي التي تسيطر عليها. كما شكل بداية انهيار قوات الدعم السريع في المنطقة. غضبًا من خيانة كيكل، شنت قوات الدعم السريع حملة انتقامية وحشية ضد مجموعته العرقية، الشكرية.

ومع ذلك، استغلت القوات المسلحة السودانية هذا الهجوم الانتقامي، حيث انضم أفراد من مجموعة الشكرية العرقية إلى القوات المسلحة السودانية تحت لواء قوات درع السودان.([22]) ردت القوات المسلحة السودانية بقوة على قوات الدعم السريع، وفتحت جبهات قتال متعددة في شرق الجزيرة وأم القرى – حيث بدأت العملية الهجومية للقوات المسلحة السودانية في الجزيرة. فتح الهجوم المضاد لقوات درع السودان جبهات قتال إضافية، مما أدى إلى تشتيت وإرباك قوات الدعم السريع التي لم تستطع مواكبة ذلك. هذا مهد الطريق لاستعادة القوات المسلحة السودانية لولاية الجزيرة، وهو انتصار حاسم زاد من زعزعة استقرار قوات الدعم السريع. من الجزيرة، بدأت القوات المسلحة السودانية وحلفاؤها في الحشد نحو ولاية الخرطوم. لعبت قوات درع السودان، على وجه الخصوص، دورًا رئيسيًا في إخراج قوات الدعم السريع من بحري وجنوب الخرطوم (انظر الخريطة أدناه).

لقد وضعت هذه التحالفات التي تم بناؤها بعناية القوات المسلحة السودانية في موقع قوي لتحييد حلفاء قوات الدعم السريع. من خلال توحيد الخصومات المحلية ضد قوات الدعم السريع وترسيخ نفسها في هياكل الإدارة الأهلية، ضمنت القوات المسلحة السودانية امتداد نفوذها إلى ما هو أبعد من ساحة المعركة، لتشكل النسيج السياسي والاجتماعي للمنطقة.

تنقسم قوات الدعم السريع وسط صراعات داخلية

تزامن التقدم الاستراتيجي والمكاسب في السيطرة على الأراضي من قبل القوات المسلحة السودانية في وسط السودان مع زيادة في الاضطرابات الداخلية في صفوف قوات الدعم السريع التي بدأت في أغسطس 2024. بمساعدة انشقاقات قوات الدعم السريع في أكتوبر، استعادت القوات المسلحة السودانية في النهاية ولاية الجزيرة، الأمر الذي أثار بدوره المزيد من الانقسامات داخل صفوف قوات الدعم السريع في منطقة الوسط، مما مكن هجوم القوات المسلحة السودانية على الخرطوم. يرجع التوسع المبكر لقوات الدعم السريع في الخرطوم والجزيرة في عام 2023 إلى نهجها اللامركزي في التجنيد والحكم، مما سمح لها بتعزيز سيطرتها على طرق الإمداد واللوجستيات الرئيسية خلال الأشهر الثمانية عشر الأولى من الصراع. ولكن بدلًا من أن تعمل كجيش موحد ذي تسلسل قيادي متماسك، عملت قوات الدعم السريع بشكل أشبه بتحالف مكون من ميليشيات محلية تربطها مصالح مشتركة. أدت هذه البنية الفضفاضة في النهاية إلى خلق أرض خصبة للمنافسة الداخلية بين القادة الطموحين. يمكن تفسير ظهور فصائل متنافسة بحلول نهاية عام 2024 بطرق تجنيد قوات الدعم السريع، التي اعتمدت بشكل كبير على المكونات العرقية والقبلية.

تاريخيًا، تتمتع المجتمعات في دارفور بتقليد يُعرف باسم “الفزع”، والذي يتضمن حشد المقاتلين من خلال الهياكل القبلية.([23]) استخدمت قوات الدعم السريع الشبكات المجتمعية القائمة للتجنيد من خلال استهداف العشائر والقبائل عبر قادتهم المجتمعيين وهياكلهم القبلية.([24])

دعم التحالف المبكر لقوات الدعم السريع مع ميليشيات عرقية، مثل بني هلبة والسلامات والرزيقات والمسيرية، توسعها السريع ومكنها من أن تصبح سلطة الأمر الواقع في الحزام الجنوبي لدارفور وكردفان بحلول نهاية عام 2023. بعيدا عن دارفور، سمح التحالف مع كيكل في منطقة الوسط لقوات الدعم السريع بالسيطرة على الجزيرة وسنار، وهما منطقتان كانتا ستكونان غير مألوفتين لحلفاء قوات الدعم السريع الأساسيين في دارفور. أدى هذا النهج إلى قوة لامركزية ومنظمة أفقيًا تعزز ولاءً كبيرًا بين الجنود ذوي الرتب الدنيا ورؤسائهم المباشرين.([25])

استراتيجية التجنيد العرقي/المجتمعي لقوات الدعم السريع أدت إلى ظهور قادة ميليشيات قبلية مستقلين من المستوى المتوسط سيطروا على الاقتصادات المحلية وسلاسل الإمداد وقادوا قواتهم في اشتباكات غذتها أجندات محلية. ([26]) هذا الهيكل اللامركزي لا يضمن سلسلة قيادة متماسكة، كما تجلى ذلك لأول مرة في الاشتباكات الدامية بين الجماعات العربية المتحالفة مع قوات الدعم السريع على الأراضي والموارد في جنوب ووسط دارفور في أواخر عام 2023، والتي استمرت لأشهر على الرغم من محاولات الوساطة من قبل قيادة قوات الدعم السريع. ([27])

نمط التنافس بين حلفاء قوات الدعم السريع توسع خارج إقليم دارفور، وسجل مشروع (ACLED) العديد من هذه الأحداث في ولايتي الجزيرة والخرطوم (انظر الرسم البياني أدناه). تعلق النزاعات الداخلية في الغالب بالانتماء العرقي أو رفض الانصياع لأوامر القيادة العليا. في 11 سبتمبر 2024، على سبيل المثال، أطلقت مجموعة من قوات الدعم السريع تتكون من جماعات عرقية غير محددة النار وقتلت مسؤول الإعلام في قوات الدعم السريع في منطقة المحيريبا بولاية الجزيرة، بعد الاعتراض على تعيينه قائداً لتلك المنطقة.

أدت هذه الحوادث إلى تراجع الروح المعنوية بشكل أكبر، وبلغت ذروتها في انشقاق كيكل في 20 أكتوبر 2024 والهجمات الانتقامية اللاحقة التي شنتها قوات الدعم السريع على المدنيين في شرق الجزيرة. بعد انشقاقه، اعتقلت قوات الدعم السريع أعضاء آخرين من قوات الدعم السريع وإدارتها المدنية الذين تم تعيينهم في ود مدني في مارس 2024، متهمة إياهم بالوقوف إلى جانب المنشقين. على الرغم من حملة القمع الشديدة التي شنتها قوات الدعم السريع على المدنيين، إلا أنها فقدت ولاية الجزيرة بعد شهرين من انشقاق كيكل، مما يشير إلى أن هذا الحدث أدى إلى خسائر كبيرة في صفوف قوات الدعم السريع في الولاية.

استمر الاقتتال الداخلي بين الميليشيات المتحالفة مع قوات الدعم السريع في الخرطوم. في ديسمبر 2024، اشتبكت مجموعة من أفراد قوات الدعم السريع من مجتمع المسيرية بقيادة القائد البارز رحمة الله المهدي، المعروف باسم “جلحة”، مع أفراد آخرين من قوات الدعم السريع في سجن سوبا بالخرطوم لثلاثة أيام متتالية. لم تنته الاشتباكات إلا بعد أن دمروا بوابات السجن وأطلقوا سراح أفراد آخرين من قوات الدعم السريع كانوا قد اعتقلوا من قبل لجنة الظواهر السلبية التابعة للمجموعة، وهي قوة شرطة داخلية تم إنشاؤها لمكافحة المخالفات في المناطق التي تسيطر عليها قوات الدعم السريع. ([28]) كان جلحة – الذي قُتل في 28 يناير 2025 – قائد ميليشيا قاتل في ليبيا وعاد للانضمام إلى قوات الدعم السريع في سبتمبر 2023. ([29]) على الرغم من محاولات قيادة قوات الدعم السريع السيطرة على قواتها، لا تزال الميليشيات المتحالفة تعمل بشكل شبه مستقل، وكثير منها تحت قيادة مرتزقة أو أمراء حرب محليين يعطون الأولوية للمكاسب الاقتصادية السريعة.

على الرغم من انتشار قوات الدعم السريع في العديد من مناطق السودان، إلا أنها فشلت في إرساء نموذج موثوق للحكم يتجاوز أنظمة الضرائب المحلية والتصاريح ونقاط التفتيش، والتي لعبت أيضًا دورًا في تفكك قوات الدعم السريع في المنطقة الوسطى. على الرغم من تعيين قوات الدعم السريع لإداراتها المدنية التابعة لها، إلا أنها لم تتمكن من الحفاظ على بيئة آمنة للسكان داخل أراضيها. أكثر من 68% من أعمال العنف التي استهدفت المدنيين والتي سجلها مشروع (ACLED) منذ بداية النزاع ارتكبتها قوات الدعم السريع، مما يشير إلى تسامح أكبر مع النشاط الإجرامي في المناطق الخاضعة لسيطرتها. ([30]) إن السماح لأفرادها بالاستقلالية في إدارة الأسواق واستراتيجيات الضرائب مكّن قوات الدعم السريع من الهيمنة على الاقتصادات المحلية وطرق الوصول الرئيسية، وعزل المناطق التي تسيطر عليها القوات المسلحة السودانية وتسهيل التجنيد القسري والتعاون من السكان المحليين والمخبرين.

ومع ذلك، فقد عزز هذا النهج ثقافة النهب وإعطاء الأولوية لغنائم الحرب بين الميليشيات المتحالفة مع قوات الدعم السريع، مما أدى في النهاية إلى تفاقم المنافسة بين وحدات قوات الدعم السريع ودفع بعض الفصائل إلى التمرد على الأوامر لتأمين مكاسب اقتصادية. على سبيل المثال، في 14 سبتمبر 2024، اشتبكت ميليشيات تابعة لقوات الدعم السريع بقيادة إسماعيل حسين وبشير بلنجة في أم روابة بولاية شمال كردفان، بسبب نزاع حول أبقار مسروقة، مما أسفر عن 13 قتيلاً. بعد خمسة أيام، وقعت اشتباكات أخرى عندما قاومت مجموعة من مقاتلي قوات الدعم السريع أمرًا بحظر الدراجات النارية والمركبات التي تستخدمها الميليشيات عادة في نهب المدنيين.

علاوة على ذلك، أدت تقدمات القوات المسلحة السودانية في أوائل عام 2025 إلى إضعاف كبير لمواقع قوات الدعم السريع المتبقية في وسط السودان. كان لسيطرة القوات المسلحة السودانية على ولاية الجزيرة تأثير كبير بشكل خاص، لأنها تربط استراتيجيًا عدة ولايات وتوفر مزايا اقتصادية قيمة كانت تستغلها قوات الدعم السريع سابقًا من خلال السيطرة على الإنتاج الزراعي والإمدادات الغذائية. ([31]) كما أن التقدمات اللاحقة التي حققتها القوات المسلحة السودانية في الخرطوم وشمال كردفان في فبراير 2025 زادت من الضغط على قوات الدعم السريع، مما حد من عملياتها وشبكة إمدادها وأدى إلى فقدانها غالبية الخرطوم بحلول مارس 2025.

تظل التحالفات حاسمة لتقدم القوات المسلحة السودانية جنوبًا وغربًا

بينما تستعيد القوات المسلحة السودانية غالبية ولاية الخرطوم وتسعى للحصول على دعم لإعادة الإعمار، من المرجح أن يتحول الصراع غربًا وجنوبًا. ([32]) في الخرطوم، نجحت القوات المسلحة السودانية في دفع قوات الدعم السريع للتراجع غربًا نحو جنوب أم درمان – معقلها الوحيد المتبقي في منطقة عاصمة المدن الثلاث – الذي يربط الخرطوم بولايتي شمال كردفان والنيل الأبيض. على الرغم من أن قوات الدعم السريع لا تزال تحاصر الأبيض من الغرب، إلا أن القوات المسلحة السودانية رفعت الحصار جزئيًا عن المدينة وربطتها بالمنطقة الجنوبية الشرقية الخاضعة لسيطرة القوات المسلحة السودانية، مما يشير إلى أنها ستُستخدم لتعزيز الهجمات المستقبلية للقوات المسلحة السودانية في المنطقة الغربية. ([33]) للحد من هجوم القوات المسلحة السودانية في الغرب، بدأت قوات الدعم السريع في قصف عاصمة شمال كردفان في 7 مارس وحشدت قواتها لمهاجمة مدينة النهود بولاية غرب كردفان الخاضعة لسيطرة القوات المسلحة السودانية.

بينما تتجه عملية الهجوم التي تشنها القوات المسلحة السودانية غربًا نحو معقل قوات الدعم السريع في دارفور، تصعد قوات الدعم السريع جهودها للاستيلاء على الفاشر، عاصمة شمال دارفور وآخر عاصمة ولاية خارج سيطرة قوات الدعم السريع في دارفور. إن استيلاء قوات الدعم السريع على بلدة المالحة الاستراتيجية – الواقعة على الطريق الذي يربط شمال دارفور بالولاية الشمالية الخاضعة لسيطرة القوات المسلحة السودانية – في 20 مارس يدل على خطة المجموعة لعرقلة تعزيزات القوات المسلحة السودانية إلى الفاشر وإضعاف قوات دارفور المشتركة. ([34]) بالنسبة لكلا الطرفين المتحاربين، تعتبر التحالفات مع الجماعات المسلحة المحلية والقوى الأجنبية حاسمة لامتلاك اليد العليا في معركة دارفور. إن تحالفات القوات المسلحة السودانية الراسخة في دارفور تسهل التحشيد للقوات المسلحة السودانية بين المجتمعات غير العربية والعربية، مما يعطل شبكة قوات الدعم السريع في المنطقة. من ناحية أخرى، فإن إمكانية وصول قوات الدعم السريع إلى مقاتلين من المنطقة والدول المجاورة مثل ليبيا وتشاد وجنوب السودان، إلى جانب معدات عسكرية متطورة، بما في ذلك الطائرات المسيرة، سيجعل معركة دارفور وهزيمة قوات الدعم السريع في معقلها أكثر صعوبة بالنسبة للقوات المسلحة السودانية وحلفائها.

في الجنوب، إن تحالف قوات الدعم السريع الأخير مع الحركة الشعبية لتحرير السودان – شمال بقيادة عبد العزيز الحلو مدد شريان حياة بالغ الأهمية، مما مكّن قوات الدعم السريع من إعادة تجميع صفوفها في المناطق التي تسيطر عليها الحركة الشعبية لتحرير السودان – شمال في ولايتي جنوب كردفان والنيل الأزرق. وقد سهّل هذا التحالف الوصول إلى الموارد المهربة عبر شبكات الحركة الشعبية لتحرير السودان – شمال على طول الحدود الجنوبية مع جنوب السودان. ([35]) لأول مرة منذ بداية النزاع، في 27 مارس، وقع هجوم بطائرة مسيرة على الدمازين، عاصمة ولاية النيل الأزرق، مما يشير إلى تحول في هجمات قوات الدعم السريع نحو الجنوب، بمساعدة تحالفها الجديد. ([36]) عبر الحدود الجنوبية، اشتبكت قوات الدعم السريع مع جماعات المعارضة الجنوب سودانية في مدينة الرنك في 15 مارس، ويبدو أنها تحالفت مع حكومة جنوب السودان. ([37]) هدد جنرالات القوات المسلحة السودانية منذ ذلك الحين بعمل عسكري ضد تشاد وجنوب السودان، متهمين الدولتين المجاورتين بدعم قوات الدعم السريع. ([38])

إن عدم احتمالية حدوث تهدئة واقعية أو وقف إطلاق نار، إلى جانب تزايد تهديدات القوات المسلحة السودانية لتشاد وجنوب السودان، يسلطان الضوء على خطر نشوب حرب، بعيدة كل البعد عن الانحسار، يمكن أن تتصاعد، وتلحق المزيد من الدمار بسكانها وتجر الدول المجاورة إليها. يمتلك كلا المتحاربين معدات عسكرية متطورة عبر جهات خارجية، مما يزيد من تأجيج تصاعد العنف في عدة مناطق. ([39]) مع استمرار الصراع، سيتحدد مستقبل الحرب في السودان بقدرة الأطراف المتحاربة على الحفاظ على تحالفاتها، والتخفيف من حدة الانقسام، وإدارة الحلفاء و أجنداتهم المتنافسة بشكل فعال.

[1] Sudan Tribune, “Sudan RSF leader says Khartoum withdrawal tactical,” 30 March 2025

[2] Aidan Lewis, “Sudan’s conflict: Who is backing the rival commanders?” Reuters, 12 April 2024; Khalid Abdelaziz, Parisa Hafezi, and Aidan Lewis, “Sudan civil war: are Iranian drones helping the army gain ground?” Reuters, 10 April 2024; Voice of America, “SAF, RSF Conflict Threatens Sudan’s Eastern Border,” 1 February 2024; Sudan Tribune, “Russia offers ‘uncapped’ military aid to Sudan,” 30 April 2024; Andrew McGregor, “Russia Switches Sides in Sudan War,” The Jamestown Foundation, 8 July 2024; United Nations Security Council, “Final report of the Panel of Experts on the Sudan,” 15 January 2024; Middle East Monitor, “Khartoum again accuses UAE of supporting Rapid Support Forces,” 15 October 2024

[3] The headquarters comprises five main buildings — the Army Headquarters, Navy Command, Air Force Headquarters, Military Intelligence, and the Ministry of Defence. (3) يتألف المقر الرئيسي من خمسة مبانٍ رئيسية – مقر قيادة الجيش، وقيادة القوات البحرية، ومقر قيادة القوات الجوية، والاستخبارات العسكرية، ووزارة الدفاع.

[4] Khalid Abdelaziz, “Sudan parallel government offers route to diplomatic leverage and arms for RSF,” Reuters, 28 February 2025

[5] Sudan Tribune, “Missile strikes hit government buildings in Sudan’s El Daein and Nyala,” 16 March 2025

[6] Middle East Eye, “Sudan: Soldiers accuse army of betrayal after retreat leaves Wad Madani to RSF,” 20 December 2023

[7] Hudhaifa Ebrahim, “EXCLUSIVE: Murders, Rapes, Hangings Rampant in War-Torn Sudan, Smuggled Birth Control Pills Draw Premium,” The Media Line, 2 January 2024; Strategic Initiative for Women in the Horn of Africa, “Statement: CSOs Condemn the Escalating Violence in Sudan as the War reaches Wad Madani and Al Gezira State,” 24 December 2023

[8] UN OCHA, “Sudan Humanitarian Update,” 28 December 2023

[9] Xinhua, “Army chief’s call for arming civilians sparks controversy in Sudan,” 7 January 2024

[10] Youseif Basher, “Sudan: Armed Popular Resistance and Widening Civil Unrest,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 15 February 2024

[11] European Union Agency for Asylum, “Sudan – Country Focus Security situation in selected areas and selected profiles affected by the conflict,” April 2024

[12] Sudan Tribune, “Al-Burhan welcomes Darfur groups in ‘Battle of Dignity,’ calls for future integration,” 21 February 2024

[13] Sudan Tribune, “Al-Burhan welcomes Darfur groups in ‘Battle of Dignity,’ calls for future integration,” 21 February 2024

[14] International Crisis Group, “Halting the Catastrophic Battle for Sudan’s El Fasher,” 24 June 2024

[15] Radio Dabanga, “Sudan Armed Forces: ‘Popular Defence Forces dissolved, not absorbed,’” 6 September 2020

[16] Ayin Network, “The Al-Bara Ibn Malik Brigade: a lifeline to the army or a lifelong challenge,” 14 June 2024

[17] Osama Abu Bakr, “Sudan’s Armed Militias and the Crisis of Civil Democratic Transition,” Arab Reform Initiative, 6 July 2023

[18] Munzoul A. M. Assal, “War in Sudan 15 April 2023: Background, analysis, and Scenarios,” International IDEA, August 2023

[19] Mohammed Amin, “Sudan’s biggest self-described ‘jihadi’ group says it will disband once RSF defeated,” Middle East Eye, 12 March 2025

[20] Al Ghad, “Al-Burhan issues a decision to pardon all Rapid Support Forces members who lay down their weapons,” 18 April 2023; Al Jazeera, “Sudan’s army claims first defection of senior RSF commander,” 20 October 2025; Sudan Tribune, “Sudan’s Burhan vows to pursue RSF until defeated,” 14 January 2025

[21] Sudan Tribune, “Central Sudan’s new armed group of Al-Butana region,” 22 December 2022; ImArabic, “Abu Aqilah Kekel, Commander of Sudan’s Shield Forces, Announces His Joining with His Forces and Equipment to the Rapid Support Forces,” 8 August 2023

[22] Samir Ramzy, “‘Tribalization’ of Sudan’s Conflict: Incentives, Restraints and Potential Trajectories,” Emirates Policy Center, 22 November 2025

[23] Julie Flint, “The Other War: Inter-Arab Conflict in Darfur,” Small Arms Survey, 10 October 2010

[24] Radio Dabanga, “Sudan’s RSF ‘stoke ethnic tensions with tribal recruitment,’” 11 November 2024; Human Rights Watch, “‘The Massalit Will Not Come Home’: Ethnic Cleansing and Crimes Against Humanity in El Geneina, West Darfur, Sudan,” 9 May 2024

[25] Paul Staniland, “Networks of Rebellion: Explaining Insurgent Cohesion and Collapse,” Cornell University Press, 2014

[26] Tahani Maala, “Beyond the Battlefield: The Survival Politics of the RSF Militia in Sudan,” African Arguments, 14 October 2024

[27] Sudan War Monitor, “Fierce fighting in South Darfur involving RSF-backed Arab militias,” 13 August 2023

[28] Nafisa Eltahir and Khalid Abdelaziz, “Unruly RSF fighters sow chaos in Sudan’s farming heartland,” Reuters, 9 August 2024

[29] Sudan Tribune, “RSF commander ‘Jalha’ killed under unclear circumstances,” 28 January 2025

[30] New York Times, “How ‘Trophy’ Videos Link Paramilitary Commanders to War Crimes in Sudan,” 31 December 2024

[31] Tamer Abd Elkreem and Susanne Jaspars, “Sudan’s catastrophe: the role of changing dynamics of food and power in the Gezira agricultural scheme,” 30 October 2024

[32] International Crisis Group, “Two Years On, Sudan’s War is Spreading,” 7 April 2025

[33] Basillioh Rukanga, “Sudan army ends two-year siege of key city,” BBC News, 24 February 2025

[34] Sudan War Monitor, “RSF captures strategic desert city in North Darfur,” 20 March 2025

[35] Mat Nashed, “Is Sudan’s war merging with South Sudanese conflicts?” Al Jazeera, 29 March 2025

[36] Genocide Watch, “Sudan army takes control of Khartoum, RSF holds Darfur,” 30 March 2025

[37] Sudan Post, “SPLA-IO generals killed in clashes with RSF in Renk County village,” 17 March 2025

[38] Reuters, “South Sudan and Chad condemn Sudanese general’s threats to attack them,” 24 March 2025

[39] Human Rights Watch, “Sudan: Abusive Warring Parties Acquire New Weapons,” 9 September 2024

الرسومات بواسطة كريستيان جافي.