Watch the recorded webinar examining the impacts of this shift in posture toward civilians in Cabo Delgado.

In March 2025, a senior figure in Mozambique’s Local Force, a government-backed militia on the front line against Islamic State Mozambique (ISM), stated that Rwandan forces in northern Mozambique’s Cabo Delgado province are now unwilling to engage with ISM militarily. He claimed that the Rwandan forces often turned up hours after an attack, even when they were located nearby. He also noted how ISM is based close to the N380 highway, and “take advantage of any opportunity” to attack.1Zumbo FM, “Cabo Delgado: Head of Discipline of the Local Force denounces Rwandan troops for acting in isolation, without coordination with Mozambican forces,” 24 March 2025 (Portuguese)

Rwandan forces have been deployed in Mozambique’s Cabo Delgado province since July 2021, following an ISM attack on Palma town that led to the suspension of the nearby liquefied natural gas (LNG) project. The 20 billion US dollar project is potentially transformative for Mozambique’s economy and society. Troops were deployed one month before the Southern African Development Community Mission in Mozambique (SAMIM), with frontline troops from Botswana, Lesotho, South Africa, and Tanzania. In that time, Rwanda has made a significant contribution to controlling the near eight-year Islamist insurgency. In doing so, they have built a reputation for effective counter-insurgency while centering civilian protection in their operations. Almost four years later, SAMIM has withdrawn from Cabo Delgado, while Rwanda’s troop numbers have doubled.

The Local Force official’s allegation is a serious one, primarily for citizens in Cabo Delgado subject to ISM attacks. The allegation is also of wider importance. Rwanda has put military cooperation at the heart of its foreign policy on the continent.2Federico Donelli, “Rwanda’s new military diplomacy,” IFRI, Note n. 31, 2022 The deployment of over 4,000 troops in Mozambique is perhaps the most important of Rwanda’s overseas missions after its engagement in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Troop numbers in Cabo Delgado are almost double those on United Nations peacekeeping duty in South Sudan.3United Nations Peacekeeping, “UNMISS Fact Sheet,” accessed 2 April 2025 Rwanda also has UN peacekeeping troops in the Central African Republic, alongside a bilateral deployment under a similar agreement as it has with Mozambique.4UN Peacekeeping, “MINUSCA Fact Sheet,” accessed 2 April 2025; Republic of Rwanda, “Central African Republic enrols new soldiers trained by RDF,” Ministry of Defence, 24 November 2023 Rwanda’s troops in Mozambique exceed its combined missions in CAR by approximately one-third.

Notwithstanding that Rwandan forces have prioritized civilian protection, there are signs that Rwanda’s current posture in northern Mozambique may put civilians at risk through either inaction or delayed reaction. This is seen in particular on the N380.

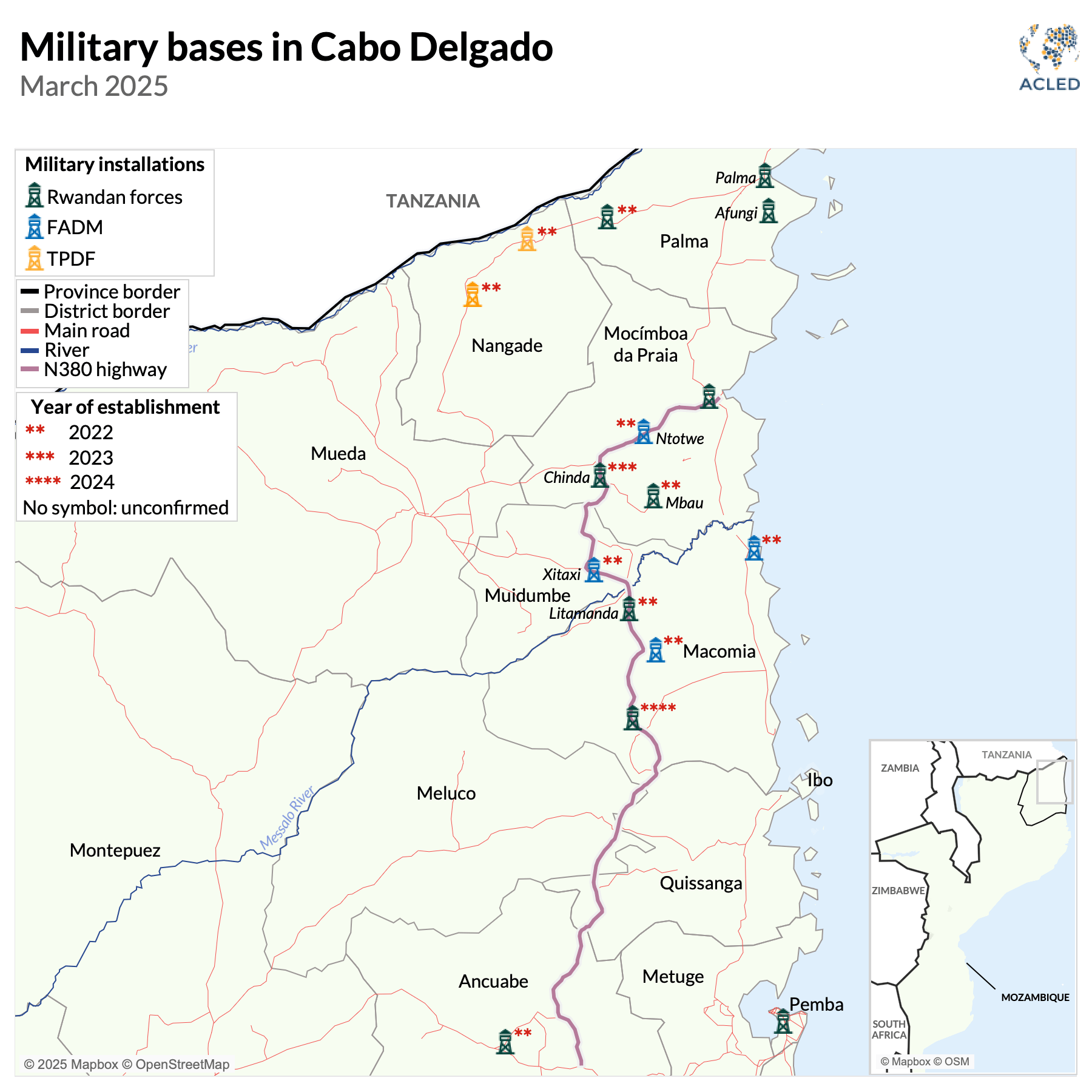

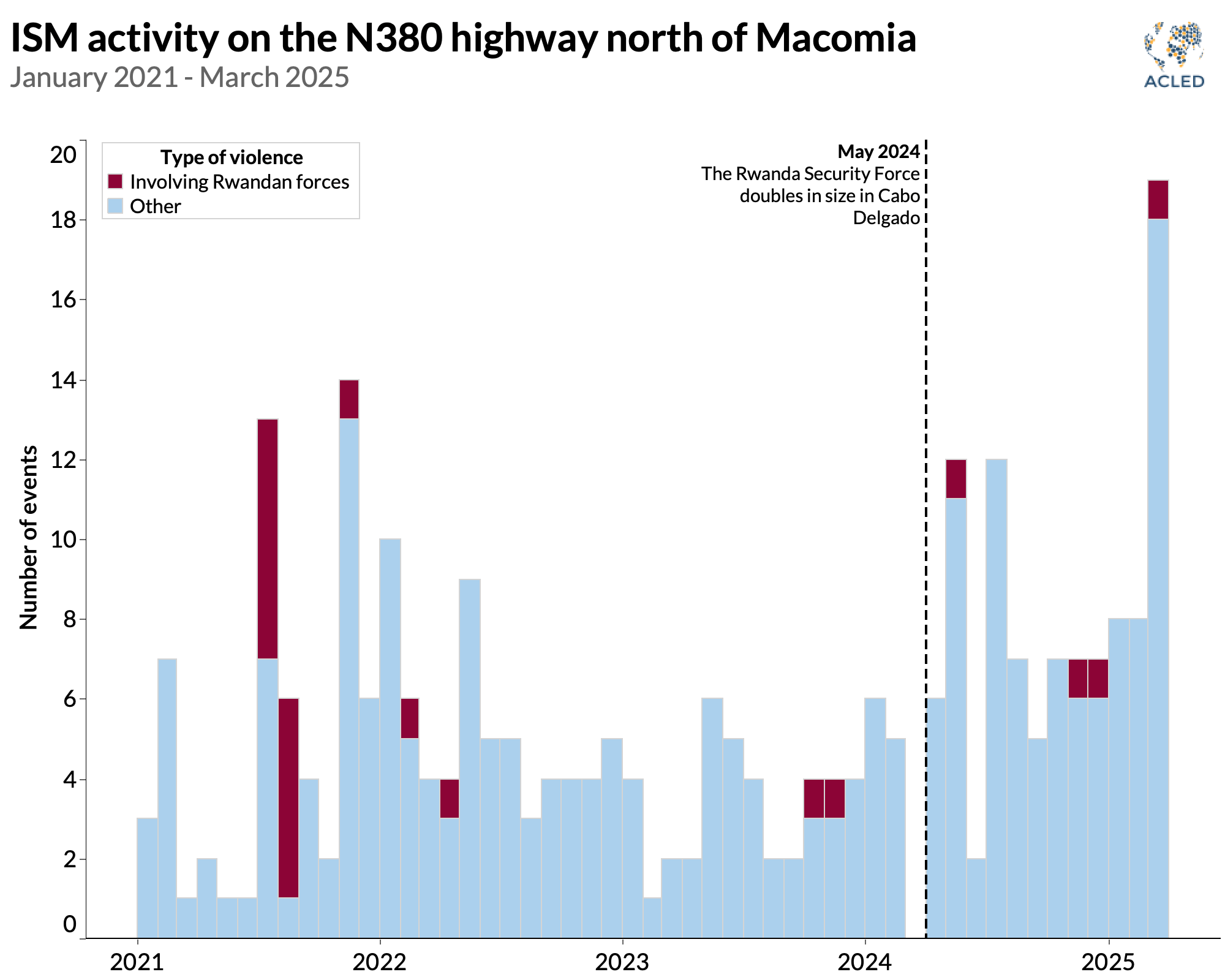

Running from the provincial capital Pemba in the south, through Macomia, to the port town of Mocímboa da Praia in the north, the N380 highway is critical to the flow of people and goods through the province. Moreover, securing the road is a critical element in securing the LNG project at Afungi in Palma district. The 145-kilometer stretch between Macomia town and Mocímboa da Praia has been most affected by the insurgency. Along this stretch are at least seven positions, four Rwandan and three of the Defense Armed Forces of Mozambique (FADM). Despite this presence, evidence indicates that Local Force allegations that state forces are unresponsive are not misplaced. This evidence is drawn from ACLED’s conflict event data for incidents along this stretch of road, combined with evidence for the locations of Rwandan and Mozambican forces in the same area drawn from satellite imagery, statements by the government of Rwanda, and local sources.

Rwanda embeds in Mozambique

With over 4,000 troops in Cabo Delgado province, the RSF is the best-trained, best-equipped, and most experienced force positioned against ISM. The force had considerable early success through 2022, allowing it to establish a high-profile presence through a network of bases and outposts across Mocímboa da Praia and Palma districts, as well as in northern Macomia and Ancuabe in the south. With the increase in forces following SAMIM’s departure, the force’s footprint is now much wider.

Deployment and early success

When Rwanda first deployed forces in Mozambique in July 2021, it sent a Joint Task Force comprised of Rwanda Defence Force (RDF) and Rwanda National Police (RNP) troops, albeit dominated and commanded by the RDF. The deployment of this combined Rwanda Security Force (RSF) was agreed over a series of meetings in Kigali and Paris starting in April 2021, after the March 2021 insurgents’ attack on Palma, and built on strong bilateral relations between the two countries that had been developed over the previous eight years.

The RSF initially deployed in Palma and Mocímboa da Praia districts, likely given the importance of the LNG project to both the Mozambican government and the insurgents. The project is situated in Palma district, while the port town of Mocímboa da Praia is critical to the project and, more broadly, is the commercial center of the province’s northern districts. The insurgency had its immediate roots in Mocímboa da Praia town, where the first shots were fired in 2017. Both districts had been closely targeted by the insurgents thereafter.

Rwandan forces regained control of Palma and Mocímboa da Praia districts by 2022. The FADM had tried for one year without success to regain control of the N380 and secure access to Mocímboa da Praia, which insurgents had controlled since August 2020. In a sustained offensive over just three weeks in July and August 2021, Rwandan forces took control of the key towns of Diaca and Awasse on the N380 approaching the town, and eventually the town itself in the first week of August. They then concentrated on dislodging insurgents from bases south of Mocímboa da Praia and in Messalo river valley. Palma town and the wider district, never held by ISM, had been more easily secured by early 2022.

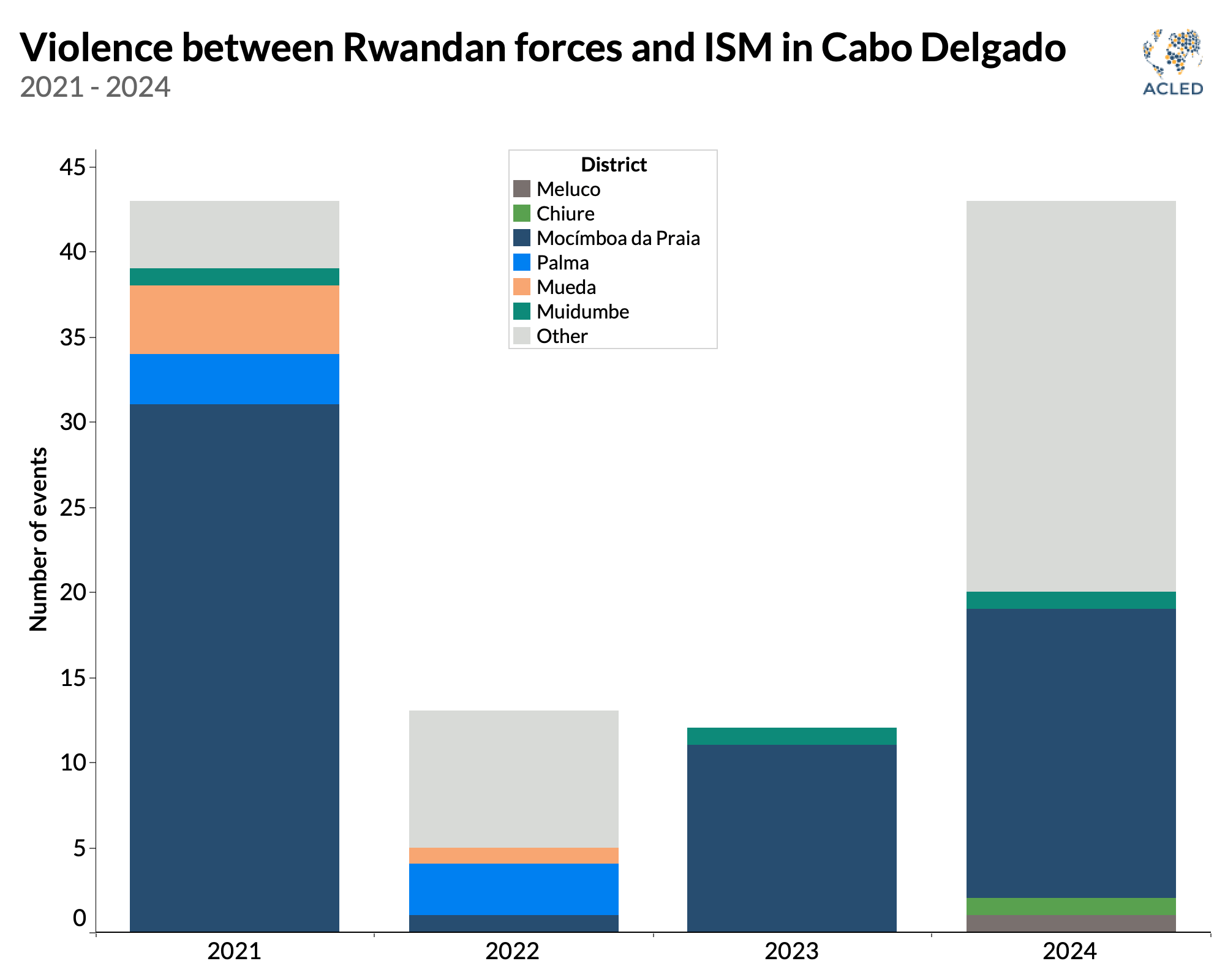

Early operations were also expansive. In 2021, Rwandan forces were active in six of the province’s northern districts, from Mueda in the west to Palma and Mocímboa da Praia in the east. This continued into 2022, but by 2023, Rwandan forces’ engagement with ISM was confined to Mocímboa da Praia and Muidumbe districts (see graph below). This reflected how firmly Palma has been secured, and the continuing presence of small groups in those two districts, particularly along the hard-to-access Messalo river basin.

With concentrated infantry operations in the early months, Rwanda overran large ISM bases, broke up the group, and disrupted supply chains. The aggressive approach sought to overwhelm insurgent forces with greater firepower and skills, and a willingness to take casualties.5Stig Jarle Hansen, “Mosaic; counter-insurgency approaches and the war against the Islamic state in Mozambique,” Small Wars and Insurgencies, 21 October 2024 The capture of major bases in late 2021 resulted in a significant loss of equipment and broke up the group significantly.6VOA Português, “Dozens of teenagers and women kidnapped by insurgents in Cabo Delgado released,” 16 September 2021 (Portuguese) Insurgent numbers were estimated by the Southern African Development Community, in a pre-intervention assessment, at up to 3,000 fighters prior to intervention.7Southern African Development Community, “Extraordinary Meeting Of The Ministerial Committee Of The Organ Troika Plus The Personnel Contributing Countries And The Republic Of Mozambique, Pretoria, Republic Of South Africa, 25 November 2021 Draft Annotated Agenda,” 21 November 2025. Leaked document via WhatsApp By mid-2022, the number of fighters was estimated at between 200 and 400. They were mostly scattered and forced to operate in small groups.8UN Security Council, “Thirtieth report of the Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team,” 15 July 2022 Consequently, supply chains that had supported such operations broke, placing considerable strain on remaining members.

Rwanda digs in

Since the start of their mission, Rwandan forces have had a significant presence in Mocímboa da Praia and Palma districts. The forces’ headquarters are in Mocímboa da Praia town, while they have a presence at the airport and at least two other sites in the town. In Palma district, there are at least three sites. The most substantial is next to the site of the LNG project at Afungi. The Rwandan forces also have a presence in Palma town. Further west in Palma district, in late 2022, the forces established a base at Pundanhar, less than 10 km from the border with Tanzania. This followed the arrival of the Tanzania People’s Defence Force (TPDF) to the neighboring Nangade district in October 2022. The deployment was under a bilateral agreement between Tanzania and Mozambique, separate from Tanzania’s troop deployment as part of SAMIM.

Rwandan forces’ operations against ISM were at their height in 2021. In 2022, with Mocímboa da Praia and Palma towns secured, they were mostly involved in sporadic operations in Macomia district. Over the course of that year and into 2023, Rwanda solidified its presence in Cabo Delgado; it established outposts along the N380, in southern Mocímboa da Praia, in Nangade district close to the border with Tanzania, and further south in Ancuabe district, close to the N1 highway (see map below). Positions in Palma, Mocímboa da Praia, and Macomia helped demarcate Rwanda’s areas of operation.

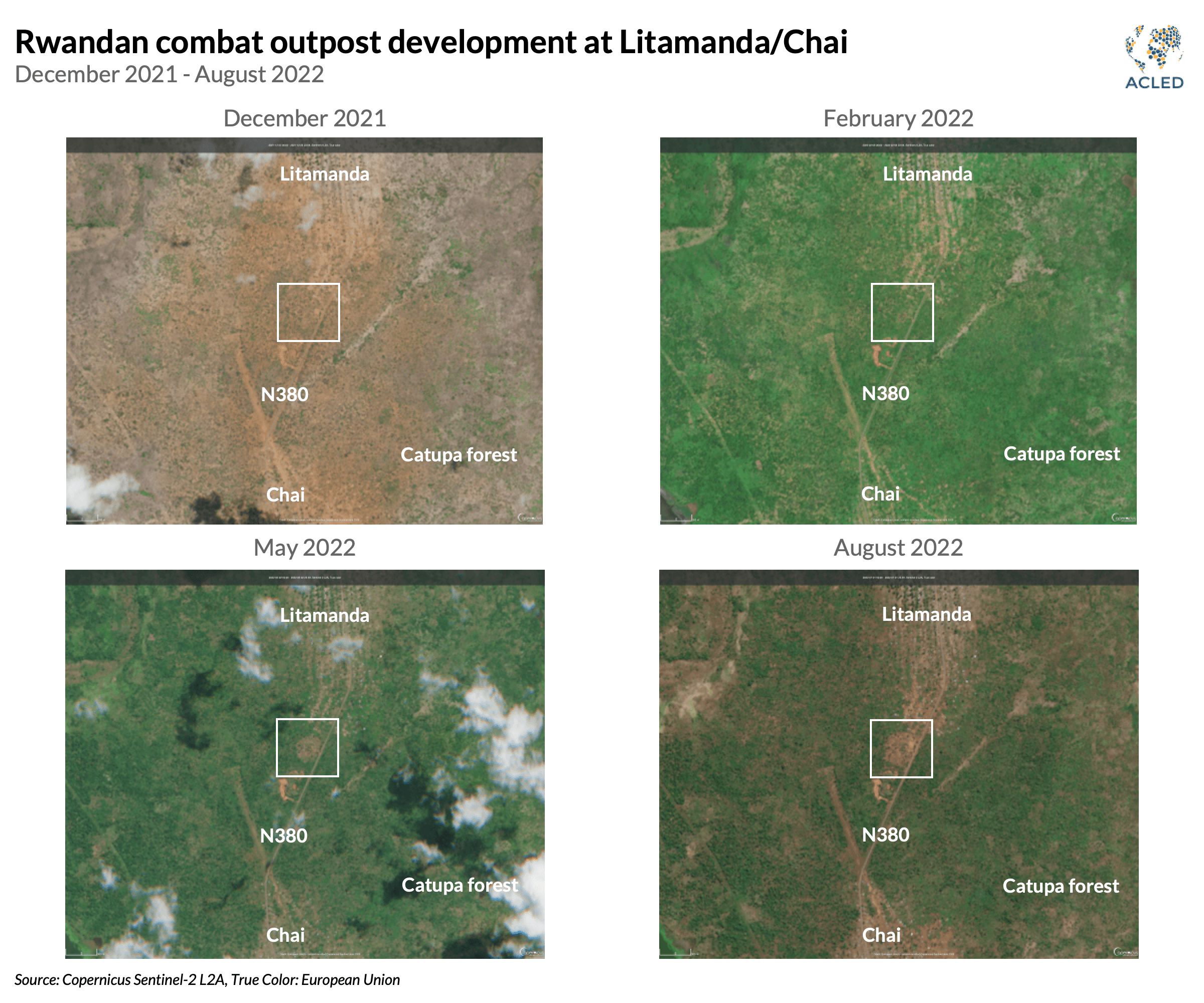

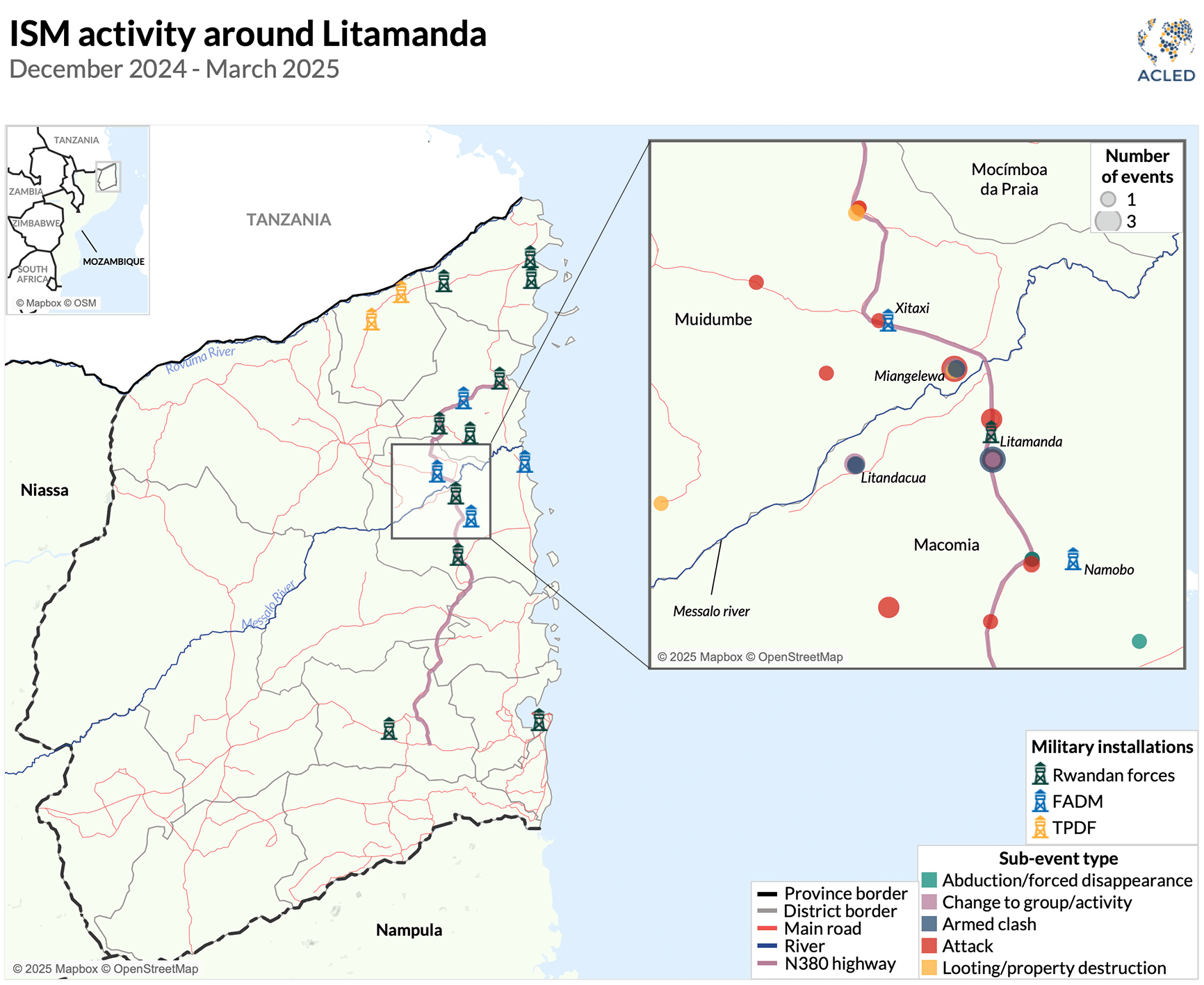

The first of these outposts was established in early 2022 on the N380 at Litamanda in Macomia district, two kilometers north of Chai town (see visual below), likely in an attempt to hold territory won in the intense fighting in 2021. The site was presumably chosen for its location along the N380 highway and its proximity to known insurgent hideouts in Catupa forest to the east and along the Messalo river, just seven kilometers north. The Litamanda outpost was complemented by another outpost located approximately 20 km northward along the N380 at Xitaxi, thought to be under FADM control. Further north, by January 2023, outposts had been established in Mocímboa da Praia district at Chinda and Ntotwe, to the south and north of the Awasse junction respectively. Chinda is an RDF outpost, while Ntotwe is thought to be a FADM outpost. In the south of Mocímboa da Praia district, Rwanda established an outpost at Mbau around November 2022, giving coverage of the eastern end of the Messalo river valley.

Outposts at Pundhanhar, Mbau, and Litamanda lay next to SAMIM’s areas of operation in Nangade, Muidumbe, and Macomia districts, and were presumably designed to complement the SAMIM presence. In December 2022, Rwanda established a foothold in southern Cabo Delgado, with an outpost in the Ancuabe district. The outpost was well-resourced, with up to 70 troops visible in images of official visits.9Republic of Rwanda, “Mozambique armed forces chief of general staff visits Rwanda Security Forces new deployment in Ancuabe district, Cabo Delgado province,” Ministry of Defence, 23 December 2022 This expansion was in response to increasing ISM activity across southern Cabo Delgado that started in June 2022 and spilled over into northern Nampula province. Almost half of this activity was in the Ancuabe district.

Civilian protection in Rwanda’s approach

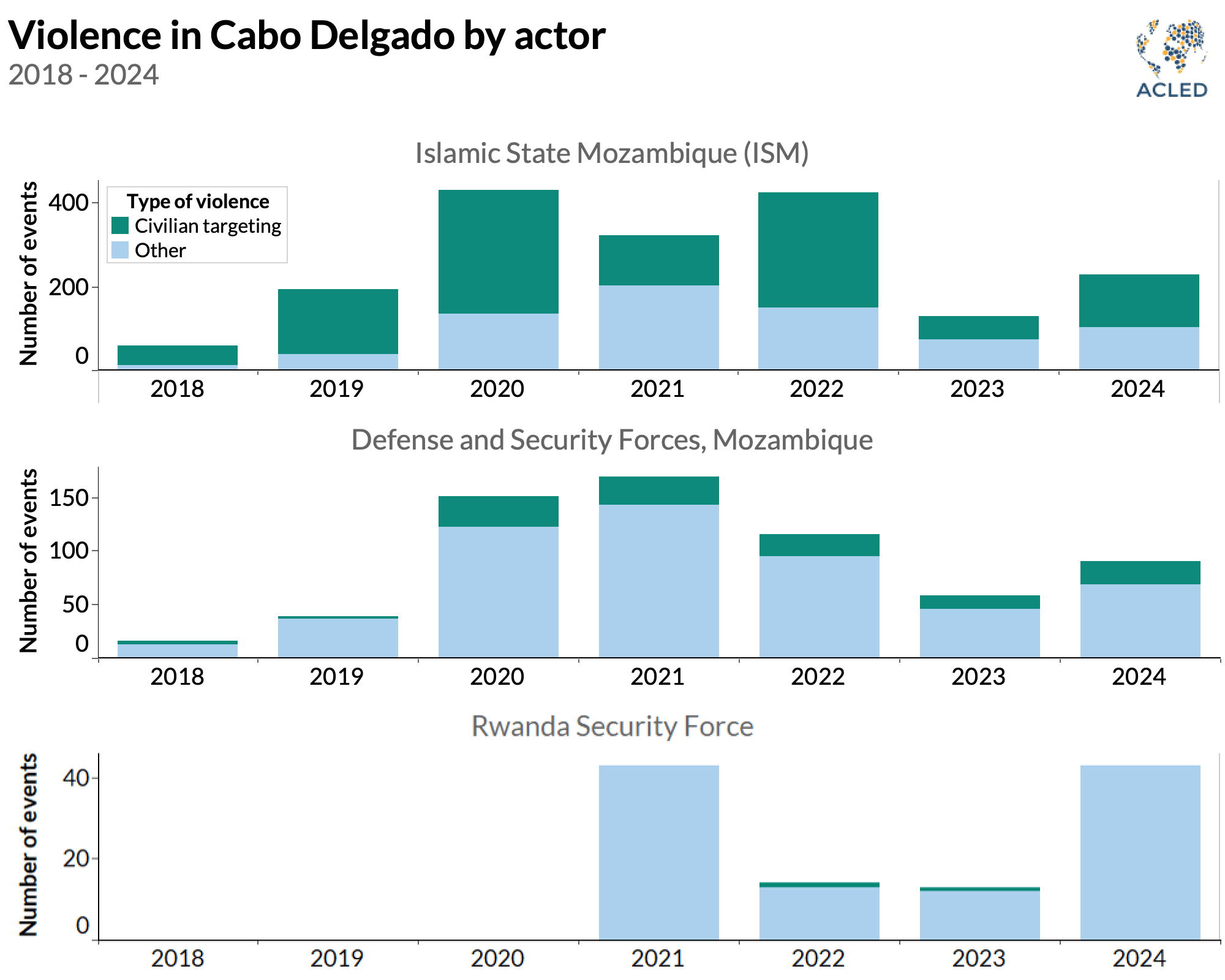

Civilians have been the primary victims of the conflict in Mozambique. Since 2018, deliberate civilian targeting has been a feature of the insurgents’ operations and activity by the Mozambican state forces. Almost 2,500 civilians have been killed in the conflict, over 40% of all fatalities. In Cabo Delgado, ACLED data indicate that the proportion of FADM violence in Cabo Delgado that targets civilians ranges from 8% to 21% annually since 2018. For police, it has been up to 50% annually. In contrast, ACLED records just two civilian targeting events by Rwandan forces in Mozambique in their three and a half years of deployment so far (see graph below). Civilian targeting events are those in which civilians are the principal, or the only, target in an event. In Cabo Delgado, these are typically incidents in which ISM launches attacks on villages during which civilians are harmed, or the killing of individuals found by the group in isolated areas, such as farmland. State violence has been less predictable, ranging from retaliatory actions against communities, unlawful detention of civilians, and, at times, criminal behavior by security forces.

Rwanda’s central role in adopting and promoting the Kigali Principles on the Protection of Civilians helps explain the low level of civilian targeting. Though they were devised for UN peacekeeping missions, they seem to have also shaped how Rwandan forces undertake counter-insurgency in Mozambique. In the first months of the insurgency, their approach was dominated by intense, kinetic engagement to regain territory and erode the insurgents’ capacity to mobilize. The forces’ subsequent posture has focused on building rapport with communities in their areas of operation. This is achieved through visible mounted patrols in lightly armored vehicles, as well as foot patrols.10Ralph Shield, “Rwanda’s War in Mozambique: Road-Testing a Kigali Principles approach to counterinsurgency? Small Wars & Insurgencies, 6 October 2023 Further underscoring their commitment to community relations is the promotion of community public works and allowing access to their health facilities. Close relations with communities that bypass government structures likely contribute to effective intelligence-gathering. A possible proxy indicator of the likelihood of this is the common practice of people appealing for Rwandan intervention when abused by Mozambican state forces.

Data show that civilian targeting by ISM increased significantly in 2022. This follows the breakup of the insurgents into small groups operating across the province. The three districts with the highest levels of such violence were Nangade, Muidumbe, and Macomia in SAMIM’s areas of operation. This seems to endorse the Rwandan approach: an initially aggressive campaign, followed by developing positions at strategic points, all complemented by a posture that focuses on community engagement. However, it presaged the challenge they would face in protecting civilians in the wake of the SAMIM withdrawal in 2024. SAMIM’s withdrawal was due to finance and operational issues, but ultimately due to Mozambique’s preference for a bilateral intervention force.11Southern African Development Community, “The Extraordinary Organ Troika Summit Plus SADC Troika, Force Intervention Brigade, (FIB) Troop Contributing Countries, SAMIM Personnel Contributing Countries and the Republic of Mozambique, 11 July 2023, Virtual Draft Annotated Agenda,” 11 July 2023. Leaked document via WhatsApp

Expansion of forces

By May 2024, Rwandan forces had approximately doubled to about 4,000 troops, as they expanded to replace SAMIM forces.12Ondiro Oganga and Matthew HIll, “Rwanda Deploys 2,000 More Troops to Gas-Rich Mozambique Region,” Bloomberg, 28 May 2024 A significant drop in ISM activity in 2023 precipitated SAMIM’s withdrawal from Cabo Delgado. While SAMIM made a significant contribution to disrupting the insurgency, its success was mixed. SAMIM troops from Lesotho and Tanzania, bolstered by the bilateral TPDF deployment, significantly reduced ISM’s presence in Nangade district, but South African forces were unable to prevent ISM from maintaining a strong base in its heartland, Macomia.

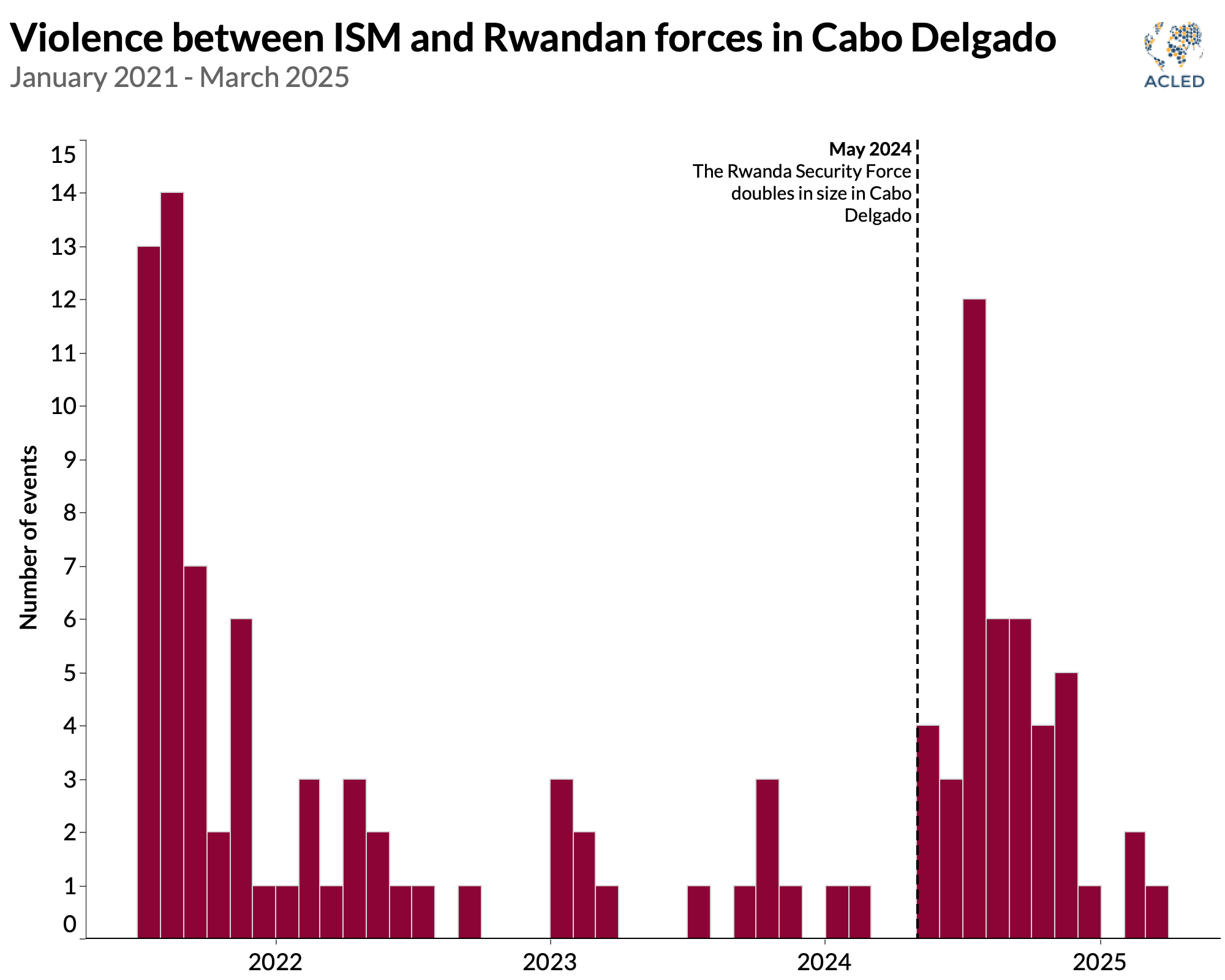

The doubling of Rwandan forces in May 2024 was followed in July by Rwanda’s most aggressive actions in Mozambique since 2021 (see graph below). At the end of July, Rwandan forces launched helicopter airstrikes against suspected ISM positions on the Macomia coast and further inland in the Catupa forest. They simultaneously launched intense ground operations in southern Mocímboa da Praia district. While occasional clashes between the RDF and ISM ensued in coastal Macomia up to December, ISM remained active in Macomia and Mocímboa da Praia and at least six other districts.

However, this aggressive approach has not been sustained. From December 2024 through March 2025, Rwandan forces have been involved in just four clashes with ISM, though it is known to have an infantry presence in communities along the Macomia coast, where ISM activity is currently low. It has also maintained its bases on the N380, which potentially have greater support from the large Rwandan base in nearby Macomia town. Consequently, ISM remains active on the Macomia coast and even more so on the N380, where its targeting of civilians drives people from their communities to centers such as Macomia and disrupts humanitarian, security, and commercial movement.

Civilian security

Despite the doubling of troops and the contracting of the insurgency, there is evidence that, in some areas, the relative risk to civilians from ISM is increasing. This is seen clearly along the N380 highway. Given the positioning of both RDF and FADM outposts along this route between Macomia town and Mocímboa da Praia and the centrality of civilian protection to RDF operations, we would expect to see a decline in ISM activity overall and a fall in the rate of civilian targeting in these areas in particular. This is not the case.

ISM and RDF activity on the militarized N380

The stretch of the N380 highway between Macomia district headquarters and Mocímboa da Praia is probably the most militarized stretch of road in Mozambique. The RDF headquarters is located at one end in Mocímboa da Praia, while at the other end, just outside Macomia town, the RDF has one of its biggest bases in the country. Along this 145-kilometer stretch lie at least four outposts, two controlled by the RSF and two controlled by FADM. They are a significant investment in the protection of civilians living on or near the route, as well as traffic along the road. The FADM position at Xitaxi and the Rwandan position at Litamanda also provide some oversight on the Messalo river basin, which has long been an insurgents’ hideout.

However, ACLED data indicate that the military presence along this route has had little effect on ISM activity. 2024 was the second-highest year for ISM activity at locations sitting on the N380 between the RDF headquarters and its Macomia base since 2020. This includes all violent activity, looting and destruction of property, and movement through these locations. But activity is not always evidence of operational strength. The movement of forces, for example, may indicate groups of ISM fighters on the run. However, looking more narrowly at ISM violence on this stretch of road, violence in 2024 was almost 70% higher than in 2023, and 2024 was the second-highest year of ISM activity on this stretch, with 2022 being the highest. The RDF was only a significant player on this route in July and August 2021, as it fought its way to Mocímboa da Praia (see graph below) before establishing its outposts or doubling its forces. It was involved in just two actions during 2022 and 2023 and three in 2024.

Civilian protection on the N380

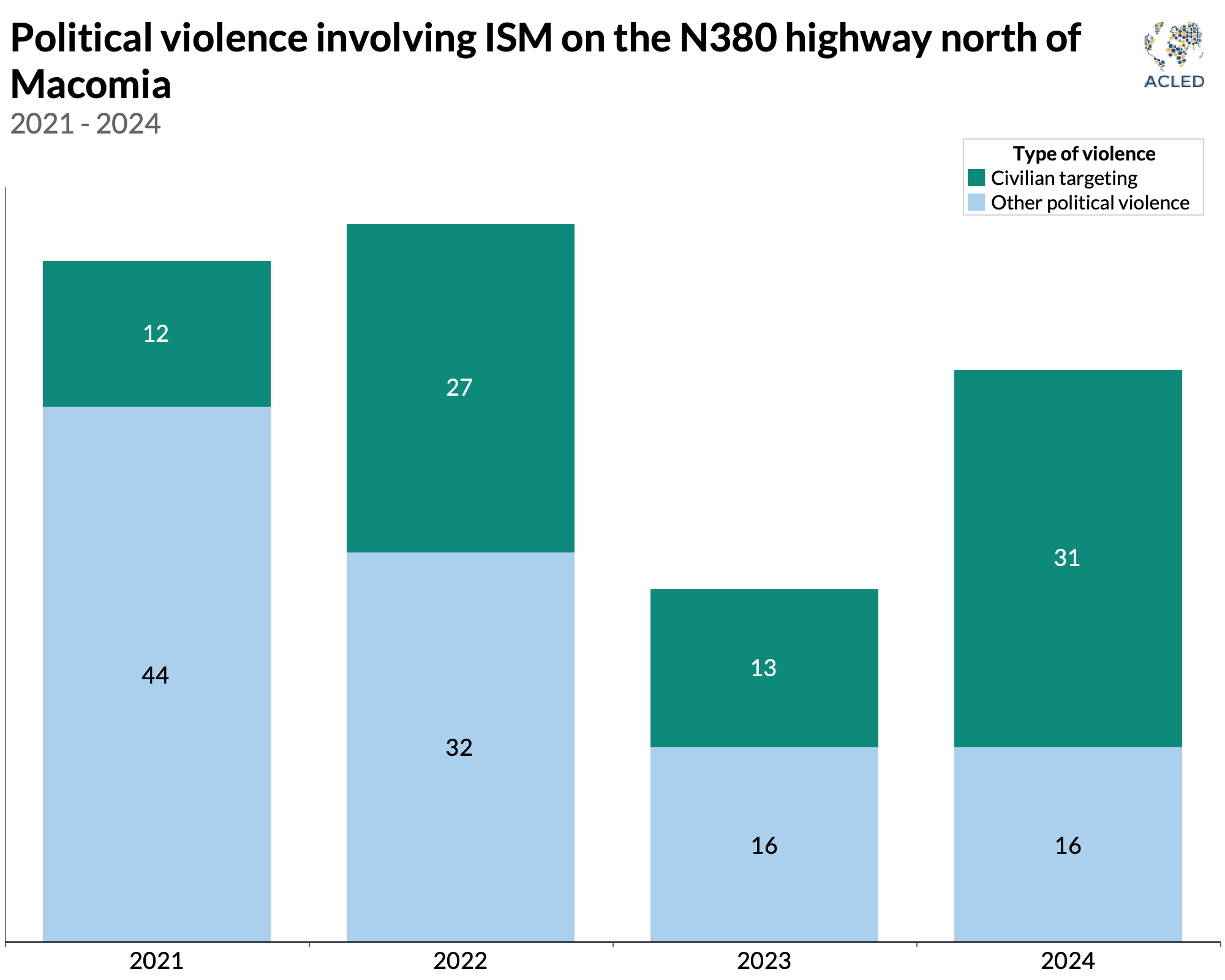

Since Rwanda’s intervention, 2024 saw the third-highest overall levels of political violence by ISM on the road from Macomia to Mocímboa da Praia, after 2022 and 2021. However, in 2024, civilian targeting by ISM along this route reached its highest point and became the most common form of violence by ISM (see graph below).

Attacks on small rural communities are unpredictable, can be undertaken by small groups, and are therefore challenging for military forces to prevent or respond to. However, looking more closely at the towns of Chai, Litamanda, and Miangelewa, a more robust response could have been expected given the presence of Rwandan troops at Litamanda, FADM at Xitaxi, and a large Rwandan base to the south in Macomia town.

Since December 2024, ISM activity around Chai, Litamanda, and Miangelewahas varied, ranging from simple movements through the area to acts of looting and property destruction and abduction of civilians and soldiers for ransom (see map below). Of all events recorded by ACLED in this area from 1 December 2024 to 31 March 2025, just five were clashes between ISM and state forces. South of the Messalo river, two clashes occurred between ISM and the Local Force in Chai and Litandacua in February. In March, ISM clashed twice with FADM and once with Rwandan forces, all related to ISM roadblocks. North of the river, ACLED records just one clash, this time when Rwandan forces responded to an ISM attack in Miangelewa in December.

The implications of unchecked ISM activity

As well as the trauma visited upon civilians, unchecked ISM activity has significant implications for ISM, Rwandan forces, and the Mozambican state’s interest in ensuring normalization of conditions in areas affected by the insurgency. Firstly, ISM fighters active in this area are likely based in temporary camps along the Messalo river and in the Catupa forest, both hard-to-access areas that have long been effective hideouts for the group. Unchecked movement, looting, and attacks on civilians allow for resupply of basic goods for fighters in that area, as well as for fighters further east on the coast.13Communications with a local informant in Cabo Delgado, ACLED, 13 February 2025

Secondly, ISM attacks on civilians are not necessarily a sign of desperation but a key plank in their strategy. This was outlined in the Islamic State’s weekly newsletter in November 2022, which stated explicitly when discussing Mozambique that the purpose of killings in one village is to spark waves of displacement from there and from neighboring villages to cities and towns “in search of lost security.”14Islamic State, “Al-Naba, No. 365,” Jihadology, 17 November 2022 This approach has had considerable success in the four months of activity around Litamanda under review. The three days of conflict around Miangelewa in mid-December resulted in almost 7,000 people fleeing to other locations in Muidumbe, Macomia town, and Mocímboa da Praia.15International Organization for Migration, “Mozambique — ETT Movement Alert Report —125 – Muidumbe (06 January 2025),” 6 January 2025 In February, ACLED records eight violent events involving ISM in the Litamanda area, six being civilian targeting events (see map above). Along with 13 people reportedly killed, over 5,500 people fled, mostly to Macomia headquarters.16International Organization for Migration, “Mozambique ETT Movement Alert Report Monthly Update_February_2025,” 4 March 2025

For Rwandan forces based in Macomia, the presence of large numbers of people displaced from areas with a Rwandan presence presents a reputational risk. Macomia town, the site of a new and significant base, sheltered over 76,000 displaced people at the last assessment undertaken in July 2024.17International Organization for Migration, “Mozambique — Mozambique — Mobility Tracking Assessment (Northern Mozambique) Round 21 (July 2024),” July 2024 There is a real risk that they may start seeing Rwandan forces as part of the problem, not the solution, if they remain unresponsive to ISM attacks on their communities.

Internationally, Rwanda’s reputation is at risk as well. Kigali presents both its peacekeeping and bilateral military deployments, as well as its actions in the DRC, as being rooted in the country’s history of genocide and failed international intervention.18YouTube, @ChathamHouse, 5 December 2024 If seen to fail in providing civilian protection in Cabo Delgado, Rwanda’s economic interests may be seen as a driver of Rwandan military cooperation in Mozambique and elsewhere.

For the Mozambican state, the actions of just a small group of insurgents operating in the northern Macomia district make a return to a conflict-free situation seem far off. ISM’s operations against civilians in rural areas are likely to continue in the foreseeable future, making displacement a chronic burden on communities, local government, and security forces, while highlighting the state’s inability to protect its people.