Q&A with

Su Mon

ACLED Senior Analyst, Asia-Pacific

The epicenter of the 7.7 magnitude earthquake that hit Myanmar on 28 March was 20 kilometers north of Sagaing town in the Sagaing region. The quake had the most devastating impact in Sagaing and Mandalay, the two regions most affected by violence since the 2021 coup. The earthquake compounded the already dire situation for civilians who face violence from the military junta. The United Nations OCHA estimates it has affected over 17 million people1UNOCHA, “Myanmar Earthquake: Humanitarian Snapshot,” 7 April 2025 in a country where 90% of the population is exposed to conflict, according to the ACLED’s Conflict Exposure tool.

The parallel National Unity Government (NUG), some ethnic armed groups, and the military have declared unilateral ceasefires, but violence persists. ACLED’s Asia-Pacific Senior Analyst Su Mon Thant explains why these ceasefires are unlikely to result in peace.

There have been four ceasefires since the 28 March earthquake, with two recently extended, but how is this situation playing out on the ground?

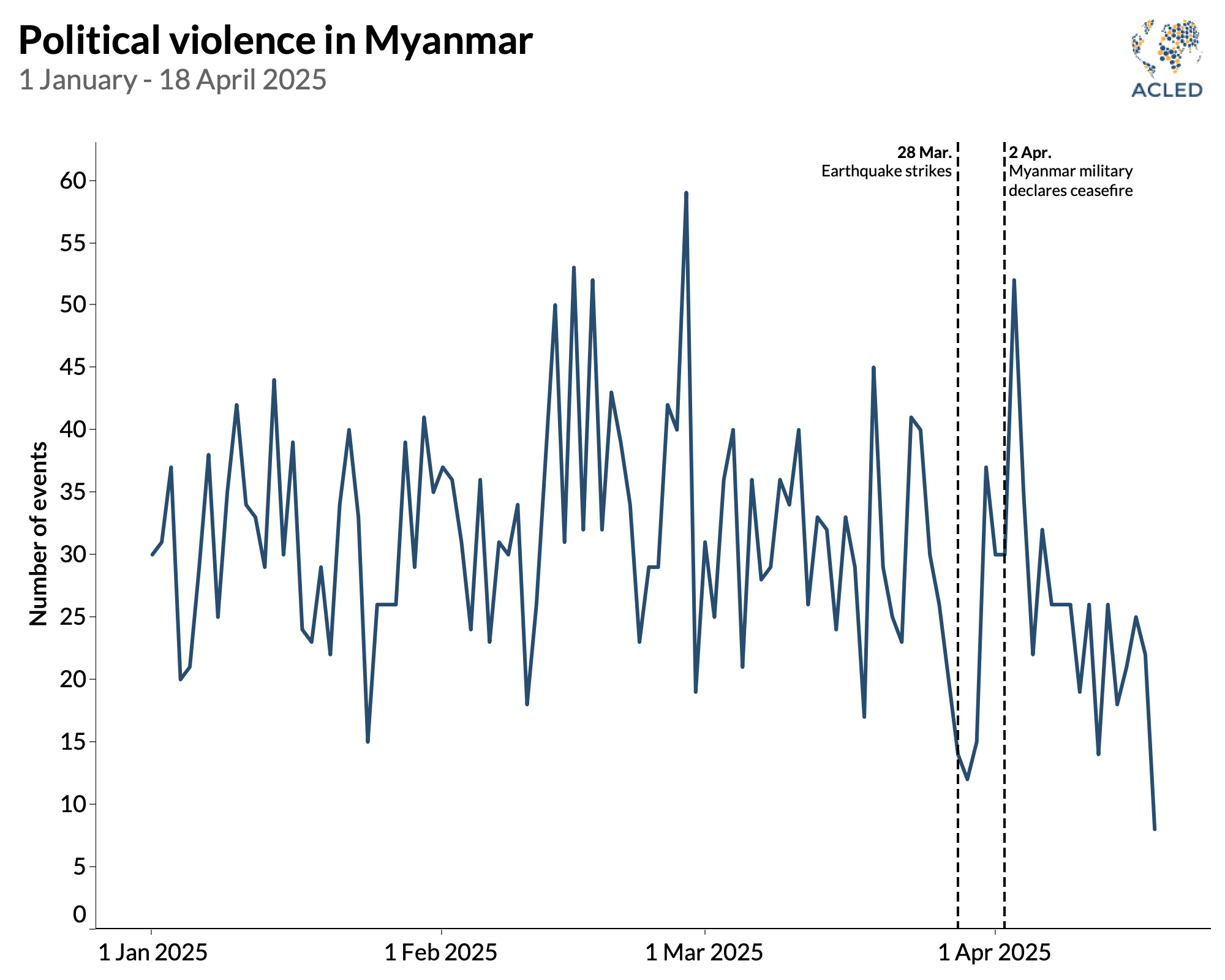

These temporary ceasefires are only for show, as violence continued in many parts of Myanmar immediately after they were announced (see graph below), including in the quake-hit Mandalay and Sagaing regions. Essentially, these ceasefires are fragile, as they are not mutual agreements and leave room for each side to interpret the other’s actions as violations, particularly in the absence of communication and cooperation mechanisms. The ceasefires announced by resistance groups reserved the right to take defensive action, while the military’s ceasefire included language for continued offensives if resistance groups were seen to be recruiting or training — activities the military considers preparations for battle.2France 24, “Myanmar military junta declares temporary ceasefire to facilitate quake relief efforts,” 2 April 2025; Mizzima, “Three Brotherhood Alliance announces one-month ceasefire for Myanmar earthquake relief,” 4 April 2025

No coordination mechanisms have been established to enforce these ceasefires between the warring parties and facilitate relief efforts. The military hasn’t lifted restrictions on internet access or travel to enable aid to reach all affected areas, including those under the resistance’s control.3Gavin Butler, “How aid becomes a weapon in Myanmar’s war zone,” BBC, 2 April 2025 Rather than seeking coordination — for example, by involving Civil Disobedience Movement participants in relief and health care — the military has kept tight control over any efforts to assist the trapped, wounded, and displaced.

The military neither deployed its forces to assist affected communities nor engaged with local organizations.4Brice Pedroletti, “After Myanmar earthquake, citizens step in amid army’s absence,” Le Monde, 6 April 2025 One particularly stark example of this lack of cooperation is the shooting at Chinese Red Cross workers heading to Mandalay through Ta’ang Army (PSLF/TNLA) territory on 1 April. This lack of cooperation not only prevents the conditions for peace but endangers lives in completely unnecessary ways.

So the violence continues. What’s the risk for civilians, particularly in these quake-affected areas?

The military is still conducting aerial strikes that target civilian populations. But this is not new; it’s been the persistent pattern of violence since the Three Brotherhood Alliance launched Operation 1027, named after the launching date on 27 October 2023, which set off a wave of battlefield losses for the military. The military has lost huge amounts of territory: nearly all of Rakhine state, huge parts of northern Shan state, and important and lucrative areas for resource exploitation in Kachin state. Many areas in the Sagaing and Mandalay regions in the center of the country are now controlled by anti-coup resistance groups.

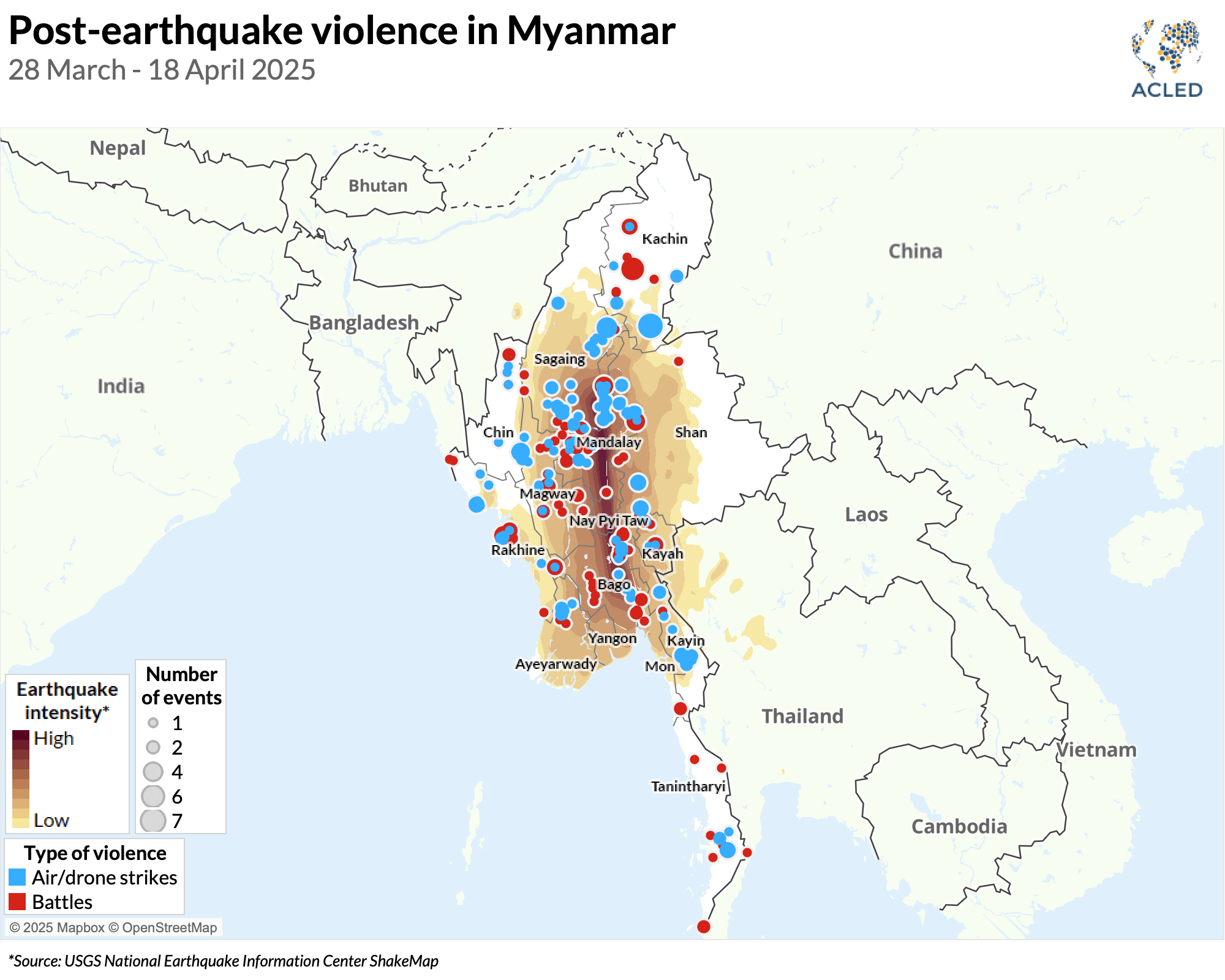

Since 2023, the military has increasingly relied on remote violence, including artillery shelling, drone strikes, paramotor attacks, and airstrikes. ACLED data show that the majority of the military’s aerial attacks since the earthquake have been in the Sagaing region and northern Shan state — areas where the military is actively attempting to regain strategic positions — as well as in Kachin and Rakhine states, where heavy fighting continues. Between 28 March and 18 April, the military carried out 211 airstrikes across 157 locations, while clashes with resistance groups — including actors who had declared ceasefires — continued in at least 86 locations (see map below).

Are there any signs that the military is willing to come to the negotiating table to avoid exacerbating the already dire situation?

There has been no political signal from the military that it aims to transform these ceasefires into a meaningful dialogue toward peace that addresses the demands of resistance groups. Before the earthquake, the military was engaged in talks with certain ethnic armed organizations such as the Kokang Army (MNTJP/MNDAA) and the PSLF/TNLA. However, the military has consistently refused to recognize the NUG, offer peace talks with the anti-coup armed groups operating under the NUG (most of which are active in the two quake-affected regions), or acknowledge their demands.

It’s important to note that ethnic armed organizations and anti-coup armed groups do not reflect actual unity or alliances. There are tensions among ethnic armed groups and among anti-coup resistance groups, and they don’t all have the same political goals beyond simply fighting the Myanmar military.

The military has long ignored calls from resistance groups for bottom-up federalism and has never hinted at any practical steps toward national reconciliation. Instead, the junta leader has announced that elections will go ahead as planned in December,5Sebastian Strangio, “Myanmar Military Chief Says Election to Be Held in December,” The Diplomat, 28 March 2025 which has been widely rejected as a stunt by resistance groups. This insistence on moving forward with elections signals that the military remains uninterested in pursuing meaningful peace negotiations.

Since 2021, ceasefires have consistently failed to lead to political talks or concessions. The current ceasefire with the MNTJP/MNDAA and the transfer of Lashio back to the military seem only to be happening because of intense pressure on the MNTJP/MNDAA from China, rather than goodwill from the military. Both the humanitarian ceasefire between the military and the Arakan Army (ULA/AA) in November 2022 and the Haigen Agreement that was signed between the military and the Three Brotherhood Alliance in January 2024 were broken within a year.

If history is any indication, ceasefires driven by humanitarian concerns and external pressures, without any trust-building or political pacts, will not last, let alone create pathways to peace.

Su Mon was speaking to ACLED Communications Coordinator, Gina Dorso, and Publications Coordinator, Niki Papadogiannaki.

- National Unity Government (NUG)

- Palaung State Liberation Front/Ta’ang National Liberation Army (PSLF/TNLA)

- Myanmar National Truth and Justice Party/Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army, or Kokang Army (MNTJP/MNDAA)

- United League of Arakan/Arakan Army (ULA/AA)

For more on Myanmar, see these related publications:

- Decisive year ahead for resistance groups in Myanmar as they threaten new territories | Conflict Watchlist 2025

- Between cooperation and competition: The struggle of resistance groups in Myanmar

- Webinar | Resistance in Myanmar: The most fragmented conflict in the world

- Four years after the 2021 coup in Myanmar, violence against civilians is still increasing

- Myanmar: 2024 Conflict Index