Q&A with

Hannah Tabara

Senior Research Assistant, ACLED

Violence around the Porgera Gold Mine in Papua New Guinea’s Enga province remains a persistent challenge, despite recent peace-building efforts. A stark example came on 2 March, when a shootout at the mine between informal miners from the Sakar tribe and state security forces left two miners dead. The clash broke out after armed miners attempted to enter a restricted area of the mine. In response to the deaths, the miners burned mining equipment, and members of the tribe damaged and blocked the highway connecting Laiagam and Porgera, disrupting travel, supply routes, and mine operations. The violence occurred despite a peace agreement that was signed on 31 January, requiring the tribe to cease informal mining near the mine. In this Q&A, Hannah Tabara, ACLED’s Senior Research Assistant based in Papua New Guinea’s Highlands region, breaks down the factors fueling violence and what might come next.

What is the cause of the violence around the Porgera Gold Mine?

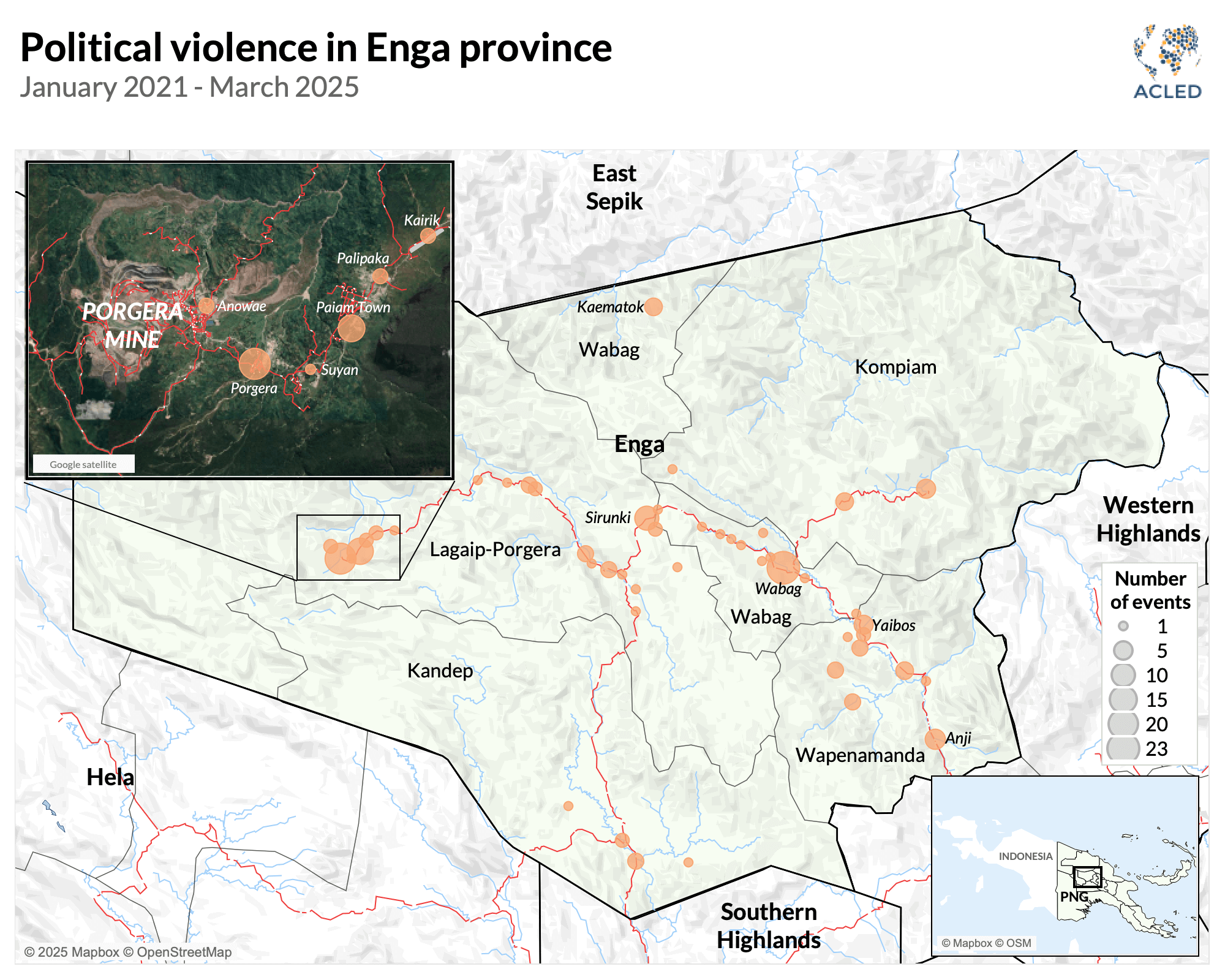

Porgera lies within Papua New Guinea’s Enga province, which has experienced persistently high levels of political violence in recent years, according to ACLED data (see map below). While tensions around the mine are often associated with disputes over mining access and benefits, they also reflect broader patterns of conflict in the province. These include ongoing challenges related to resource competition, land tenure, and limited and uneven access to government services and law enforcement that have contributed to a fragile security environment.1Julian Whayman, “A public-private partnership tackling law and order in PNG,” Devpolicy Blog, 5 June 2015 Incidents connected to the mine are not limited to the mining site itself; they can also occur along access routes and in nearby communities, highlighting how concerns linked to the mine resonate across a wider geographic and social landscape.

Within this wider context, informal mining has emerged as a particular flashpoint for violence. The Porgera Gold Mine’s history is complex, and violence around the mine stems from long-standing tribal disputes, economic pressures, and tensions over informal mining. Informal mining is largely carried out by migrants from other parts of Enga who settled around the mine over time.2The National, “Porgera valley squatters given 48-hour ultimatum, says Manning,” 5 April 2024 For these individuals, small-scale gold panning has become a primary means of earning a living since the establishment of the mine in 1990, particularly in the absence of stable employment opportunities. The mine’s early operations attracted a surge in the population around Porgera, and over the past three decades, the practice has been taken up by successive generations.3Andrew Anton Mako, “Mining in PNG: blessings, curse and lessons from the Porgera mine,” Devpolicy Blog, 21 June 2023

Many of those engaged in informal mining are not the traditional landowners, and, over time, disagreements have emerged as informal miners began working areas tied to formal agreements between landowners, the state, and Barrick Niugini Limited (BNL), the former operator of the mine. BNL is a joint venture between Canadian mining company Barrick Gold and China’s Zijin Mining, which operated the mine until 2020. Disputes over land ownership due to some clans feeling they were unfairly excluded from formal landowner agreements,4Post-Courier, “Concerns on validation in Porgera,” 28 July 2021 discontent among landowners over compensation from mine operators and the government for use of the land and the environmental degradation caused by the mining, and reports of human rights abuses have long fueled local frustration.5Mining Watch Canada, “Papua New Guinea Landowners to Challenge 29 Year Old Porgera Mine in Supreme Court,” 18 November 2018

In April 2020, the government declined to renew BNL’s license, hoping to negotiate an increase in the share that the state and the landowners own, leading to a three-year closure.6Paul Oeka, “A Look Into Porgera Gold Mine’s Lengthy Progress To Recommencement,” PNG Business News, 13 April 2023 During this time, formal employment disappeared, and informal mining expanded in the absence of regulation. Individuals, including some of the traditional landowners, felt justified in mining during the closure, citing the absence of benefits and income from formal agreements while the mine was inactive.7Post-Courier, “Benefit sharing the real issue in Porgera,” 24 September 2024 Since its reopening in December 2023, operations have been taken over by New Porgera Limited (NPL), a joint venture in which the state and landowners now hold a combined 51% share and BNL holds 49%.8Zara Kanu Lebo, “Reopened mine brings much promise,” The National, 5 January 2024 Landowners, who receive royalties and other benefits through these agreements, view informal mining as a threat to their land rights, livelihoods, and personal safety.9Harlyne Joku and Stefan Armbruster, “Landowners fear more killings despite PNG ‘state of emergency’ over mine fighting,” Benar News, 18 September 2024. The state also considers illegal mining to be a challenge to law and order around a nationally significant economic site.10Belinda Kora and Tim Swanston, “PNG government to send military and police in crack down on illegal mining and ‘squatters’ at Porgera gold mine,” ABC Australia, 10 April 2024 Porgera is vital to Papua New Guinea’s economy; at its peak in the early 2000s, the mine contributed over 10% of the country’s annual export revenues.11Paul Oeka, “A Look Into Porgera Gold Mine’s Lengthy Progress To Recommencement,” PNG Business News, 13 April 2023

Meanwhile, tensions between tribal and state law persist. Many locals still follow customary systems that don’t always align with state processes, and a lack of trust in government authorities has only deepened these divides.

What is the government doing to address informal mining in Porgera?

Recognizing its role in fueling local conflict and instability, the government has taken several approaches to addressing informal mining in Porgera. Over time, authorities have issued multiple warnings urging informal miners to stop their activities and organized multiple operations to crack down on informal mining. In September 2024, a state of emergency was declared in parts of Enga province, including Porgera, following deadly clashes between the Pianda and Sakar tribes that stemmed from disputes over informal mining.12The National, “Emergency in Porgera,” 23 September 2024 The conflict reportedly left 32 people dead and prompted the deployment of state security forces under strict directives, including controversial shoot-to-kill orders.

To complement security responses, the government has also supported peacebuilding efforts. In January 2025, a peace agreement, called the Porgera Peace Accords, was signed between the Pianda and Sakar tribes along with the state security forces. The tribes committed to halting informal mining activities near the site and working toward sustained peace and cooperation.

While the peace agreement aimed to restore order, it has been challenged by ongoing disruptions, including road blockages by local communities and the aftermath of the 2024 Mulitaka landslide that severed the main highway into Porgera.

Are the current government measures effective?

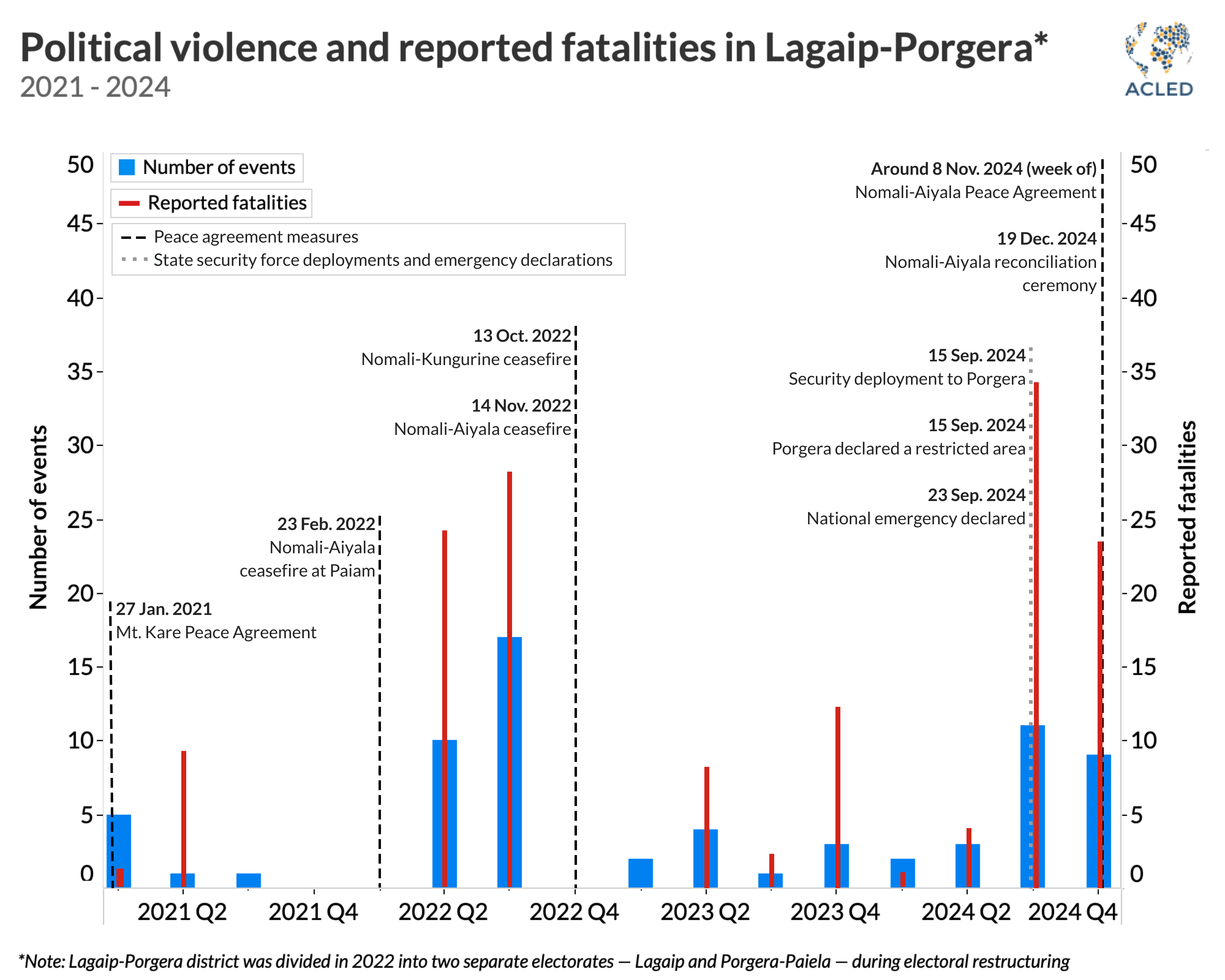

Government measures have produced periodic reductions in violence around the mine, as seen in ACLED data (see graph below). Notable drops occurred in late 2021, mid-to-late 2022, and again in mid-2023, largely coinciding with security operations, including the declaration of a state of emergency. The most recent decline came in the first quarter of 2025, following the signing of the Porgera Peace Accords in January. While this suggests the peace process has contributed to improved security conditions around the mine, sporadic incidents, like the one in March, continue to be recorded.

The incident in March exposed differing interpretations of the agreement. A spokesperson for the Sakar tribe, whose members were killed, claimed that the peace deal prohibited such killings.13Miriam Zarriga, “Laiagam road closed,” Post-Courier, 3 March 2025 This was cited as a justification for the subsequent blocking of the Laiagam-Porgera road as revenge. In response, the controller of the state of emergency publicly clarified that the agreement signed by recognized tribal leaders included a clear ban on informal mining, and that enforcement measures, including shoot-to-kill provisions for breaches, were part of the deal. After this clarification, community members lifted the roadblock. This incident suggests that there had been a lack of awareness regarding the terms of the agreement at the community level.14Ennio Kuble, “Tribe lets vehicles pass,” The National, 6 March 2025

While government measures have brought some security gains, they have been difficult to sustain, and the March episode illustrates how gaps in communication and community-level understanding can undermine implementation. The peace process may hold potential for longer stability, but its success will likely depend on how clearly its terms are communicated and how consistently they are upheld by all parties.

How is the situation likely to evolve?

If current government actions continue, patterns seen in recent years suggest that violence could continue at times. In the past, periods of calm often followed major interventions like peace agreements or emergency operations, but these were sometimes followed by renewed tensions. Respected local leaders have, at times, helped bridge the gap between state and tribal systems. If they are not consistently included in peace efforts, that gap may remain, affecting how government actions are received or followed at the local level.

While the January peace agreement represents progress toward ending violence, lasting peace will depend on consistent enforcement of the peace agreement, community engagement, and addressing the deeper social and economic drivers of informal mining in the province.

Hannah Tabara was speaking to ACLED Research Manager for East Asia Pacific, Laura Sorica, and Senior Editorial Officer, Sanet Oberholzer.

Visuals produced by Ana Marco.