A hard-won peace may be largely prevailing in the southern Philippines, but not all is quiet in the camps of the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF). As the region’s Muslim Moro people await the first ever and oft-delayed parliamentary elections of the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (BARMM), the MILF, whose decades-long separatist armed struggle culminated in a peace agreement with the national government in 2014 and the creation of the BARMM in 2019, finds itself confronted by a violence older than that of its former adversaries from the national government: war between clans, traditionally called “rido.”

It is not the violence any ideologically committed MILF fighter had arguably signed up to confront, but it has claimed the lives of many a fighter. On 10 August 2022, for example, two factions of the MILF, each identified with rival clans, engaged in a firefight in Pikit town, Cotabato, in which four people were killed, including a civilian. The fighting led to the evacuation of hundreds of villagers and required the intervention of military, police, and local government officials to stop. Similarly, on 4 September 2024, the rival Aragasi and Usman clans, both affiliated with the MILF, engaged in a firefight in Parang town, Maguindanao del Norte, killing four. The fighting erupted over a long-running land dispute between the two clans.

Such fighting related to clan blood feuds concerns not only the MILF but also the wider Moro society. Precisely for this reason, it cannot be downplayed as a threat to the peace process, especially as the fate of the around 15,000 MILF fighters who have yet to undergo decommissioning depends on the success of the BARMM polls. The first polls — delayed multiple times for different reasons ranging from COVID-19 to (most recently) the belated exclusion of Sulu province from BARMM1Herbie Gomez and Jairo Bolledo, “Supreme Court finalizes Sulu’s exit from BARMM,” Rappler, 26 November 2024; Guinevere Latoza, “Sulu’s exit shakes up Bangsamoro: 5 scenarios for the 2025 polls,” Rappler, 14 November 2024 — are understood to be the completion of the government and MILF’s mutual commitments to each other under the 2014 peace agreement. The peace process is thus entering a critical homestretch that demands just enough calm from all armed stakeholders for a full-fledged autonomous government to emerge — through the ballot box rather than through arms.

The MILF is not unaware of the persistent challenge rido poses to its own ranks and has tried for years to resolve clan conflicts between its members. When the MILF announced the end of two clan wars in 2011, it acknowledged that such rido conflicts are obstacles to peace.2Edwin Fernandez, “MILF announces end of 2 clan wars,” Philippine Daily Inquirer, 5 November 2011 Later, in June 2020, the MILF celebrated its resolution of what it called the biggest rido in the formerly unified Maguindanao province (split into Maguindanao del Norte and Maguindanao del Sur in 2022). At the time, the MILF asserted that the peace agreement between the Sindatok and Tundok clans, which respectively led the MILF’s 105th and 118th Base Commands, would eliminate “half of the rido problem in Maguindanao.”3Ferdinandh B. Cabrera, “Clans in Maguindanao’s biggest ‘rido’ bury hatchet,” Minda News, 29 June 2020

All eyes are now waiting to see whether the MILF will do better than its historical predecessor, the Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF), in dealing with rido. The MNLF, founded in 1972, signed its own peace agreement with the national government in 1996 and consequently governed the earlier Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (ARMM) region that preceded BARMM.4Institute for Policy Analysis of Conflict, “The Risk of More Violence in the Sulu Archipelago,” 15 April 2021 The MNLF-led ARMM was largely seen as a failure, not only because the MILF (which had split from the MNLF by 1977 over strategic differences)5Philippine Daily Inquirer, “Fast facts: Moro National Liberation Front,” 5 November 2016 continued its rebellion, but also because the MNLF was seen to have failed in asserting political legitimacy over powerful local clans.6Francisco J. Lara Jr., “Insurgents, Clans, and States: Political Legitimacy and Resurgent Conflict in Muslim Mindanao, Philippines,” Ateneo de Manila University Press, 2014 Rido now threatens to once again be a stumbling block to the MILF and the national government’s efforts to establish a lasting peace in Mindanao.

Rido violence and clan-based social structures in BARMM

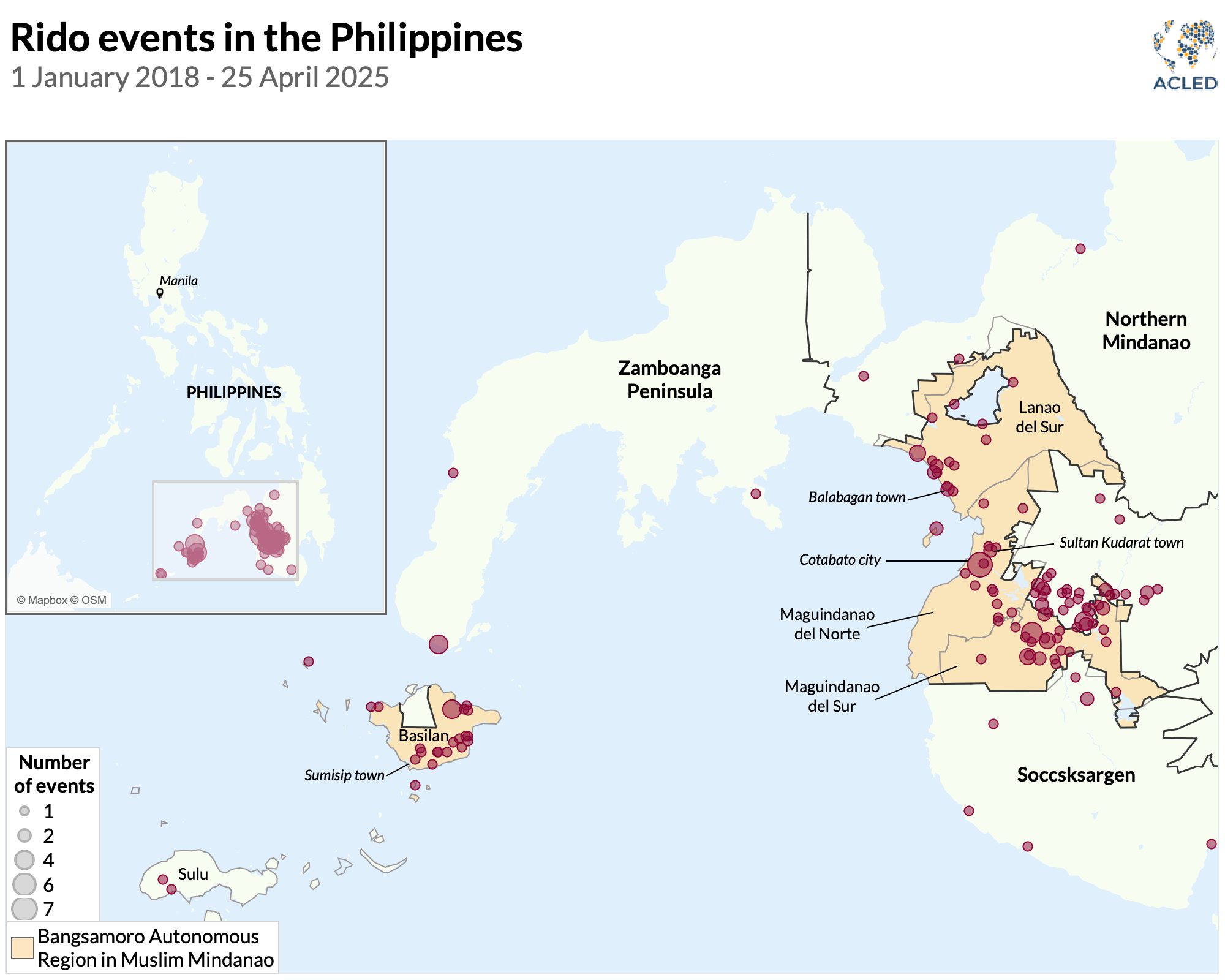

Rido violence is traditionally defined as clan-based violence between Moro Muslim clans. The existence of rido itself illustrates the strong clan-based dynamics that persist in the region, which far predate the separatist political movements that shaped Mindanao’s political history over the last few decades. ACLED records over 150 rido events since 2018. Unsurprisingly, most rido violence persists in present-day BARMM, which accounts for around 80% of all such events since 2018, but also to a significant degree in the neighboring Soccsksargen region (see map below). Most such events have no relation to MILF or other armed group activity.

Using reports of violent events from local and national media, ACLED has recorded violent incidents related to rido from 2018 onward. ACLED classifies events as rido-related if a report on political violence explicitly refers to rido as the cause or likely cause. On rare occasions when reports do not explicitly refer to rido, they may still use very similar language, referring to “clan blood feuds” or fighting between clans in the Muslim-majority part of Mindanao, the traditional homeland of the Moro people. This area is now mostly in present-day BARMM, but rido events have also been recorded in neighboring regions, including Soccsksargen, Northern Mindanao, and Zamboanga Peninsula.

Surveying ACLED data on rido violence reveals its multifaceted nature. Motives for specific outbreaks of violence range from the overtly political to the decidedly personal. Given the overall security implications and social significance of rido in clan-based Mindanao society, all such events are included in the ACLED dataset, whether they are attributed to electoral competition or a personal grudge.

One of the most cited reasons for deadly rido violence is competition over land. A firefight between the rival Impos and Magao clans on 18 September 2020, which killed two militiamen from each group, is a typical example of a clan-based dispute over land that turned lethal. But land is not the only reason cited in outbreaks of violence. For example, in April 2021, a member of the Jaljalis clan was killed by Aspali clan militiamen in Sumisip town, Basilan, after he was caught having an affair with the Aspali clan leader’s sister-in-law. The Jaljalis clan then retaliated, resulting in the death of an Aspali clan member. Meanwhile, on 10 November 2024, two cousins were reportedly killed and two others wounded in a clash between clans in Balabagan town, Lanao del Sur. The fight stemmed from a simple argument over Facebook posts. The relatives of the slain cousins retaliated by setting fire to a truck owned by the opposing side.

There are even cases reported as rido that may not involve fighting between two Moro clans. But even these cases are rooted in the complicated history of Mindanao, including the central state’s policy of resettling non-Moro Muslim people in the territory throughout the 20th century. Thus, on 25 January 2017, three members of an Ilonggo clan — non-Muslim people originating from Western Visayas in the central Philippines — were injured in a rido-related ambush by a Moro family in Sultan Kudarat town, Maguindanao. The resettling of non-Muslim (typically Christian) Filipinos throughout Mindanao that began during the American colonial era, and the resulting displacement of Moro Muslims, is one of the historical grievances that led to the Moro rebellion that began in the 1970s.7Thomas M. McKenna, “Muslim Rulers and Rebels: Everyday Politics and Armed Separatism in the Southern Philippines,” University of California Press, August 1998, pp. 114-119

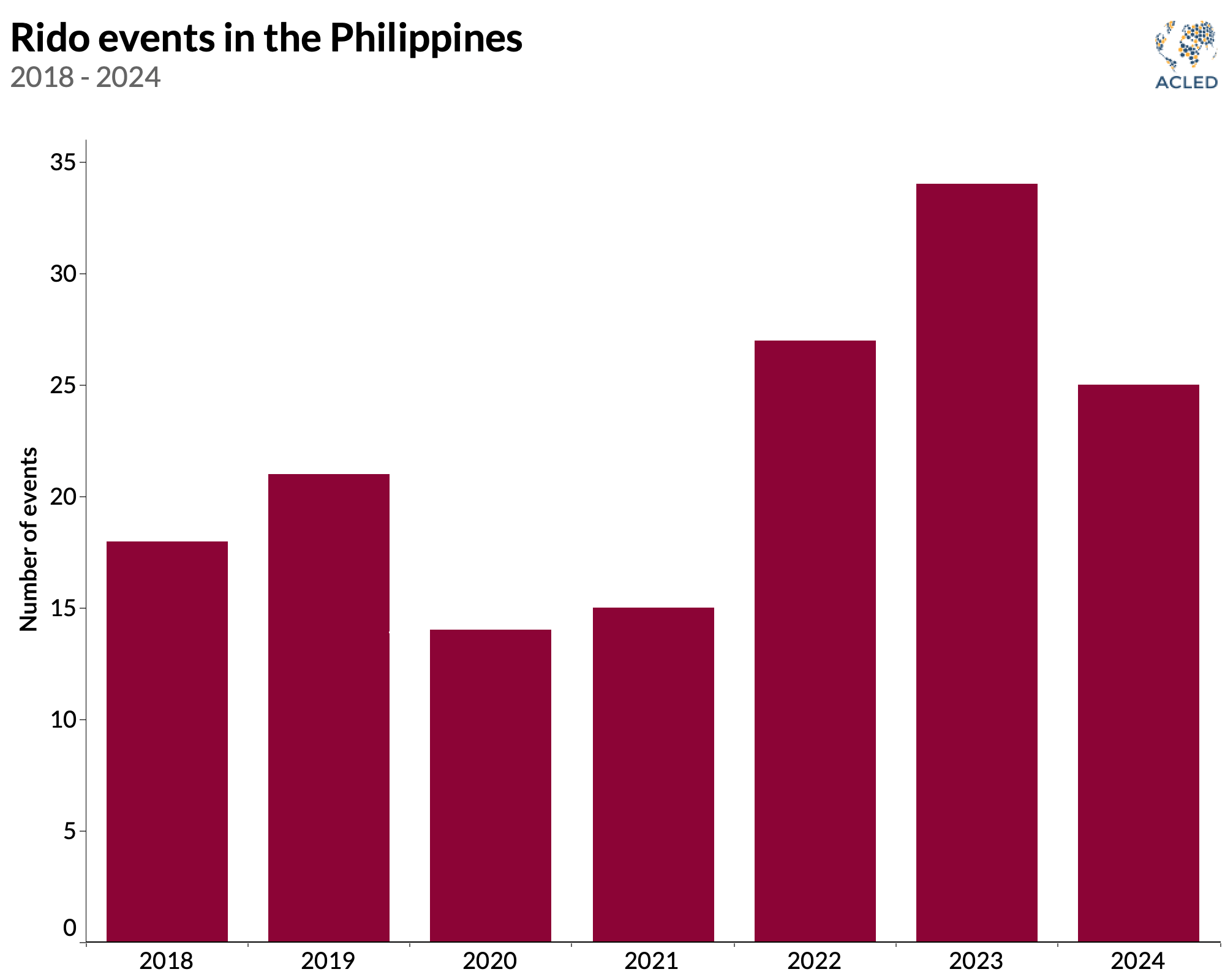

These are but a handful of examples of rido-related fighting, but there is reason to believe that rido — while highly researched by scholars — is a significantly underreported phenomenon, given that most rido incidents happen in remote places that might not always receive media attention. Thus, while ACLED data indicate a rise in rido events in the past years (see graph below), ACLED’s reports-based figure is likely an undercount. In any case, the establishment of transitional MILF-led BARMM institutions in 2019 failed to stem rido-related violence.

Rido interaction with other conflicts

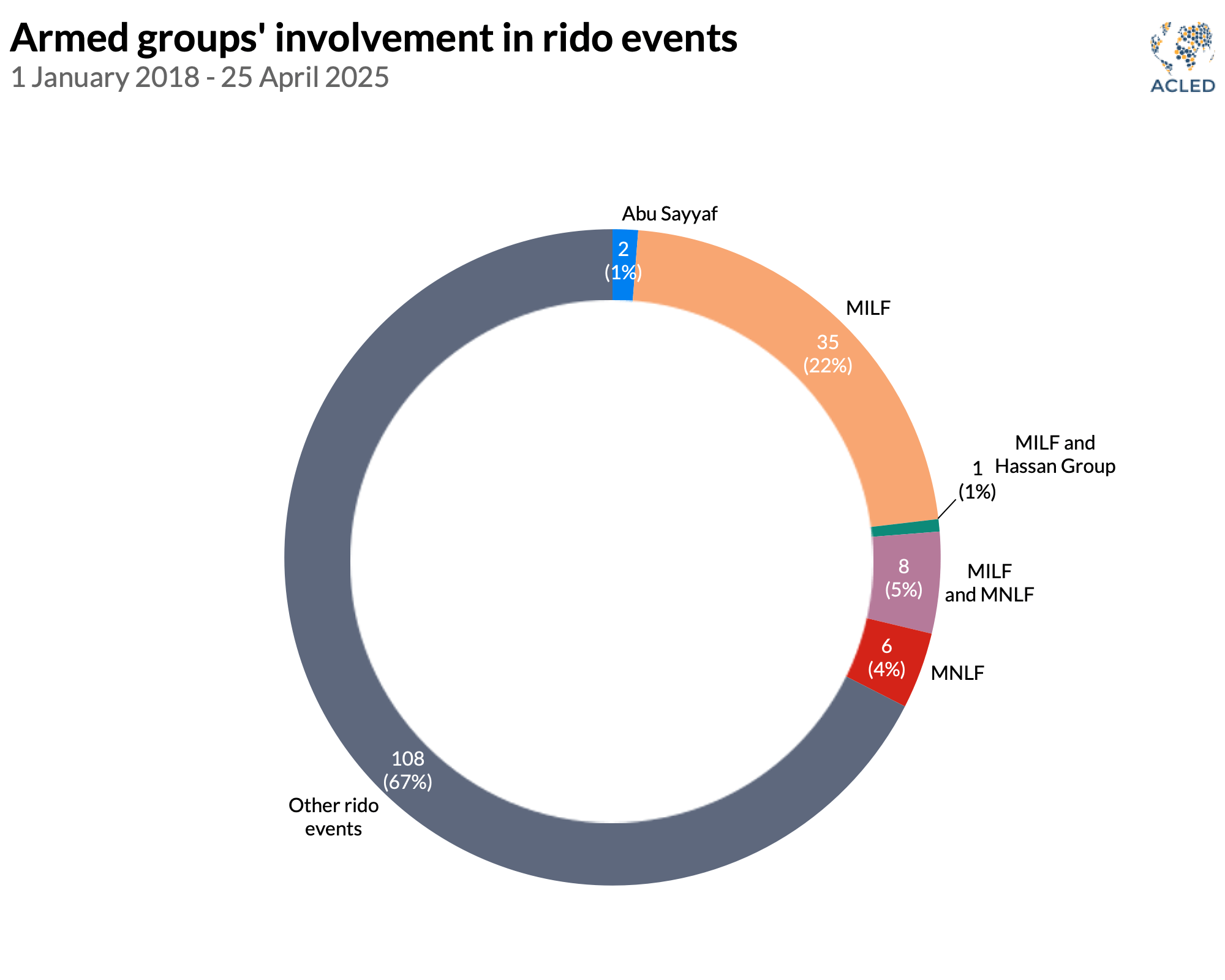

ACLED data show that the persistence of rido violence in BARMM and surrounding regions often also involves actors with identities that are not inherently centered on rido, the most prominent of which are the MILF and MNLF.

When university-educated ideologues first started waging the separatist armed struggle for the Moro people in the 1970s, giving birth first to the MNLF and later the MILF, these early revolutionaries couched their groups’ ideological language in the ideals of self-determination. But while these national separatist struggles appealed to globalized norms of self-determination, local realities play a decisive role in how such appeals turn out. The scholarship on violence in Bangsamoro has thus focused on the difficulty that new democratic structures face in establishing their political legitimacy vis-à-vis more traditional sources of political legitimacy, such as clans.8International Crisis Group, “Southern Philippines: Tackling Clan Politics in the Bangsamoro,” 14 April 2020; Wilfredo Torres III (ed.), “Rido: Clan Feuding and Conflict Management in Mindanao,” Ateneo de Manila University Press, 2014; Francisco J. Lara Jr., “Insurgents, Clans, and States: Political Legitimacy and Resurgent Conflict in Muslim Mindanao, Philippines,” Ateneo de Manila University Press, 2014; Francisco J. Lara Jr. and Nikki Philline C. de la Rosa (eds.), “Conflict’s Long Game: A Decade of Violence in the Bangsamoro,” Ateneo de Manila University Press, 2023

The MILF and MNLF movements in Mindanao have historically sought to frame their projects of political autonomy in the same terms as, paradoxically, the national state they opposed: the creation of modern political institutions that fulfill the responsibilities expected of a state. Thus, even with the shift of their political projects from full separatism to regional autonomy, the MILF and the MNLF now align themselves with the central state, as well as international development cooperation agencies, in embracing the language of “good governance” as the solution to social ills.

However, implementing international democratic norms locally will not automatically dislodge a society’s traditional sources of political legitimacy. Local populations still need convincing that new institutions will respond to their needs better than, say, the powerful local clans that previously guaranteed their security and livelihood. Such institutions will thus have to be proven more “legitimate” than the clans.9Francisco J. Lara Jr., “Insurgents, Clans, and States: Political Legitimacy and Resurgent Conflict in Muslim Mindanao, Philippines,” Ateneo de Manila University Press, 2014 In the case of Bangsamoro, good governance advocates now working in the framework of rebel-won autonomy therefore risk a disconnect with local communities if they ignore the traditional clan-based power structures, which far precede the rebellions.

What is at stake is the very authority of the rebels-turned-leaders now at the helm of the supposedly innovative and democratic new autonomous region. Their authority is quickly undermined when the violence emanating from the traditional clan-based power structures remains unchecked. This is especially true given that other armed actors otherwise engaged in conflict outside the framework of rido also take part in clan-based violence, affirming the stubborn political centrality of clans.

As ACLED data from 2018 onward show, a third of rido violence has involved the MILF, MNLF, and other armed groups, such as Abu Sayyaf and Dawlah Islamiyah affiliates like the Hassan Group, on at least one side of a clash (see graph below). Abu Sayyaf is a long-standing Islamist fundamentalist group with historic ties to al-Qaeda, while Dawlah Islamiyah is a loose umbrella term for several Islamic State-inspired groups that first rose to prominence in the mid-2010s and reached a height of activity during the 2017 siege on Marawi city. Though these diverse groups are largely connected only by their presence in Mindanao, one commonality is that none of them was inherently constituted to engage in rido violence.

The armed group whose members are most involved in rido violence is the MILF itself. In fact, of all the political violence events that have seen at least some MILF involvement since 2018, 35% are related to rido. This figure represents a considerable strain on the MILF-led BARMM’s credibility in managing rido violence in the region. It also highlights how the interconnectedness of different conflicts in Bangsamoro means that the resources available to an armed group may also play a role in pursuing goals external to the group. After all, the MILF members involved were ostensibly armed in service of the MILF’s ideological goals of political autonomy for Moro Muslims. But their implication in rido violence shows that they may also be using their weapons to serve other purposes. Rido thus compounds the volume of violence attributable to an armed group, even if such violence lies outside a group’s self-understanding.

Rido may even play a role in the occasional clashes that break out between armed groups, which otherwise — apart from the MILF and the MNLF, since their respective peace agreements with the government — would normally engage only in armed clashes with state forces. For example, on 11 September 2023, two Dawlah Islamiyah–Hassan Group militants were reportedly killed and three others wounded in a firefight with the MILF in Datu Hoffer Ampatuan town in Maguindanao del Sur. The fighting caused Teduray tribespeople to evacuate. Authorities directly blamed a long-standing rido for the fighting between the Dawlah Islamiyah and the MILF militants.

MNLF fighters, too, have engaged in firefights with the MILF. Two rival clans, respectively affiliated with the MILF and the MNLF, fought in several villages in Pikit town, Cotabato, on 10 May 2020. Despite no reports of casualties, the effects of the violence were not confined to the fighters, as the rival militias burned homes and looted property and livestock in the area. The local government, and both the MILF and MNLF, intervened to end the fighting, which was attributed to a land dispute.

These examples show that armed groups may sometimes be pulled into patterns of violence with a longer history than their own.

The threat of rido violence to the BARMM elections and the larger peace process

Elevated levels of violence have historically accompanied election periods in the Philippines, and the first-ever Bangsamoro parliamentary election is not likely to be different. In fact, several rido events have been attributed to electoral competition, and at least 26 rido-related attacks have been directed against elected representatives and other local state officials since 2018. Some specific rido-related events have also been expressly attributed to electoral competition. For example, on 24 September 2024, two individuals were reportedly killed in a clash between the Abdul and Macud clans in Malabang town, Lanao del Sur. The incident also wounded four people and led hundreds of residents to flee. The conflict was said to originate from a dispute during the 2019 local elections between the two clans.

The question for the 2025 BARMM polls would then be whether the powerful clans participating in the parliamentary elections are going to keep such competition to the ballot box or resort to violence in an attempt to influence the results. The single most prominent player in the upcoming elections is, of course, the MILF itself. Though it is officially participating in the polls through its organizationally separate affiliated political party, the United Bangsamoro Justice Party (UBJP), the MILF and its remaining armed strength of about 15,000 fighters remain this party’s backbone. After all, in line with the 2014 peace agreement, the full decommissioning process of MILF fighters is not expected to be finished until the completion of the peace process, which is meant to be capped by the polls. So far, around 25,000 MILF fighters have been decommissioned by the third of four decommissioning phases as of 2023.10Minda News, “FACT CHECK: Final phase of MILF decommissioning process is yet to start,” 22 November 2023 Government officials have publicly announced their intent to complete the decommissioning process, which includes third-party international observers, right in time for the BARMM parliamentary elections.11Bong S. Sarmiento, “Full deactivation of 40,000 MILF fighters eyed in May 2025,” 13 July 2023 With the postponement of the polls, now scheduled for October 2025, the decommissioning progress is presently unclear.

BARMM politicians who are unaffiliated with the MILF have expressed concern about the group’s continued armed strength going into the polls, as the official decommissioning protocol of the 2014 peace agreement only provides for the decommissioning of 35% of all MILF fighters by the third (pre-final) phase.12Official Gazette, “Protocol on the Implementation of the Terms of Reference (TOR) of the Independent Decommissioning Body (IDB),” 30 January 2015; Office of the Presidential Adviser on Peace, Reconciliation and Unity, “Statement of Sec. Carlito G. Galvez, Jr. on decommissioning process of the MILF combatants,” 17 November 2022 In 2023, four BARMM provincial governors called on the government to hasten the decommissioning process. The governors argued that the MILF’s armed presence, coupled with the “peace process mechanisms” in place, barred police and military from implementing law enforcement operations in areas considered “MILF territory.”13Ferdinandh B. Cabrera, “4 BARMM governors ask Palace to hasten decommissioning of MILF,” Minda News, 24 February 2023 During the 2019 autonomy plebiscite that established the BARMM, some quarters also expressed fears about a possible outbreak of violence in case Cotabato City, now the BARMM capital, did not vote to join the then-proposed autonomous region, given the city’s symbolic importance for the MILF.14Carolyn O. Arguillas, “Fear and the fight for Cotabato City’s 113,751 votes: empty streets, closed shops,” Minda News, 22 January 2019

In contrast to politicians publicly expressing concern about the MILF’s continued armed strength, the group has instead pointed to powerful local politicians’ private armies as the threat to peace and order. Responding to the BARMM governors’ call, MILF leader and former BARMM Chief Minister Ahod “Murad” Ebrahim said there was no problem with a faster decommissioning, but he emphasized the need for a corresponding dismantling of politicians’ private armies.15Ferdinand Cabrera, “MILF calls for disbandment of politicians’ private armies,” Rappler, 28 February 2023

With MILF members themselves often involved in armed clashes between clans, third-party observers have emphasized the mutual importance of decommissioning MILF fighters and dismantling clans’ private armies.16International Crisis Group, “Southern Philippines: Making Peace Stick in the Bangsamoro,” 1 May 2023 On the same track, the government has stressed the importance of instituting nonviolent resolution mechanisms for rido disputes to protect the gains of the peace process.17Priam Nepomuceno, “OPAPRU: Swift actions to address ‘rido’ to preserve BARMM peace gains,” Philippine News Agency, 25 January 2024 The MILF-led Bangsamoro transitional government has therefore engaged in regionwide consultation efforts for the prevention and settlement of rido disputes.18Bangsamoro Information Office, “Rido settlements, a key to progress and development – MPOS,” 8 June 2020

These efforts notwithstanding, the history of election-related violence in the Philippines gives reason for concern that a heightened risk of violence during the elections could be posed by confluent factors, including electoral competition between clans, electoral participation of a heavily armed MILF, and the presence of clan militias and private armies across BARMM.

Tensions will run especially high given that powerful and influential clans are fielding their members to contest the parliamentary elections. Some have even banded together to form larger coalitions to face off with the MILF’s own party — though the alliances seem to be fluid and shifting. For example, three of four regionally prominent clans that previously allied as the Bangsamoro Grand Coalition to contest the UBJP in the October 2025 polls later declared allegiance to the UBJP.19Ferdinandh Cabrera, “Maguindanao’s powerful political alliance collapses as 3 clans bolt to MILF party,” Rappler, 7 October 2024

In the face of persistent rido violence, the future Bangsamoro government will be tasked with the tall order of convincing its Moro constituents — including the powerful clans that make up its elite — that the new institutions and mechanisms will serve as a more effective recourse than rido in solving the disputes that shape Moro social life. The elections promise to be the first test. Their success will require just enough faith in the future of Bangsamoro for the MILF and clan-based militias to lay down their arms.

Contribution of The University of Texas at Austin (UT)

The data used for this report was enriched by the work of students at the University of Texas at Austin (UT). These include Owen Butler, Geraldyn Campos, Abigail Holguin, Sunny Hou, and Brian Montalvo under the direction of Dr. Ashley Moran in the UT Government Department. UT identified and tagged events of election-related disorder and violent events targeting national administrators in the Philippines between January 2018 and January 2025. The project contributes to the tracking of violence targeting administrators and understanding their manifestations in national and subnational political settings. The election-related disorder tags allow the tracking of unrest that arises during electoral processes, such as violence targeting electoral infrastructure and officials, demonstrations linked to elections (e.g. electoral reforms, contestation of results, etc.), and also violence against relatives of politicians, which is a tool frequently used by power brokers to put pressure on political figures.