Q&A with

Nancy Ezzeddine

Middle East analyst, ACLED

On 12 May 2025, the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) officially announced its decision to disband and end its armed struggle. Designated a terrorist organization by Turkey and several of its allies, the group has waged a decades-long insurgency for Kurdish autonomy and rights. This announcement followed a unilateral ceasefire declared on 1 March, after the PKK’s imprisoned leader, Abdullah Öcalan, issued a call for the group to disarm.

The PKK has previously made commitments to peace, but last week’s announcement is unprecedented. In this Q&A, ACLED Middle East Analyst Nancy Ezzeddine explains how this development compares to previous efforts, what motivates each side, and whether it marks the start of a sustainable peace process.

On 12 May 2025, the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) officially announced its decision to disband and end its armed struggle. Designated a terrorist organization by Turkey and several of its allies, the group has waged a decades-long insurgency for Kurdish autonomy and rights. This announcement followed a unilateral ceasefire declared on 1 March, after the PKK’s imprisoned leader, Abdullah Öcalan, issued a call for the group to disarm.

The PKK has previously made commitments to peace, but last week’s announcement is unprecedented. In this Q&A, ACLED Middle East Analyst Nancy Ezzeddine explains how this development compares to previous efforts, what motivates each side, and whether it marks the start of a sustainable peace process.

Does the PKK’s disbandment signal a turning point in the Kurdish-Turkish conflict?

Yes, this marks a potentially historic shift: Since the early 1990s, the PKK has announced multiple ceasefires and pauses in armed activity — in 1993, 1995, 1998-1999, and 2013 — often following appeals by Öcalan. While some sparked limited dialogue, none have led to lasting peace. The most structured effort came in 2013 when Öcalan called for PKK fighters to withdraw from Turkish territory.1Al Jazeera, “PKK ‘halts withdrawal’ from Turkey,” 9 September 2013

That process collapsed by mid-2015, triggering one of the conflict’s most violent periods. In 2016, ACLED’s first year collecting data in the region, Turkey carried out large-scale airstrikes on PKK positions in the Qandil Mountains of northern Iraq and rural areas of southeastern Turkey, particularly in Hakkâri and Şırnak provinces. In turn, the PKK and its affiliates — particularly the Kurdistan Freedom Hawks (TAK) — escalated attacks through ambushes, targeted killings, and deadly suicide bombings in urban centers such as Ankara, Istanbul, and Diyarbakır. The conflict resulted in more than 3,800 reported fatalities across 2016, a figure that has yet to be surpassed.

The PKK’s 12 May announcement to disband marks a potentially historic shift that follows months of indirect negotiations with Turkish officials. While the move is broader in scope than past initiatives, it carries similar risks. Previous efforts have consistently collapsed, often triggering renewed and intensified violence. The Turkish government has cautiously welcomed the disbandment but has yet to offer a reciprocal political roadmap or formal concessions. This creates a fragile opening: promising, yet laden with unanswered questions and a risk of collapse.

Why has the PKK chosen to disarm now?

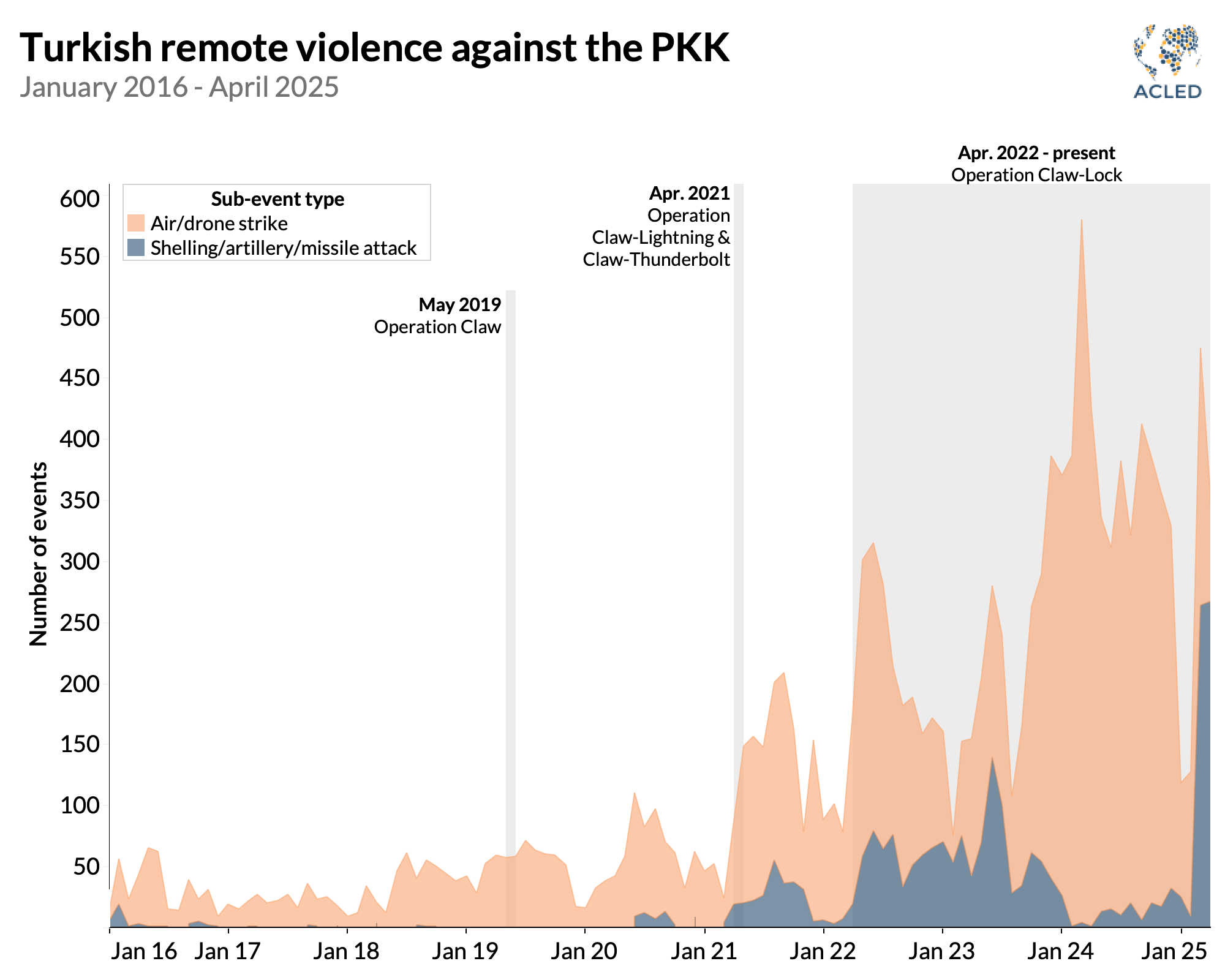

The PKK is weaker than it has ever been. Since 2019, Turkey has exponentially intensified its military campaign against the PKK through cross-border operations — Claw (2019), Claw-Lightning and Claw-Thunderbolt (2021), and Claw-Lock (2022) — targeting PKK infrastructure in Iraq and Syria. This escalation has relied heavily on airpower, particularly drones. A key shift underpinning this strategy is that the PKK has been pushed out of Turkey, with its operational presence now concentrated across the border in northern Iraq. This geographic retreat has made the group increasingly vulnerable to air and drone strikes, which surged from 414 incidents in 2018 to 4,427 in 2024 (see graph below).

Drone warfare has enabled Turkey to kill senior PKK commanders, disrupt logistics, and limit PKK movements. It has also seen the PKK retreat into mountainous zones and adopt a defensive posture.2Azhhi Rasul, “Turkey claims control of strategic mountainous area in Kurdistan,” Rudaw, 26 November 2024. PKK remote attacks have not kept pace with Turkey’s intensifying military campaign, suggesting operational limitations. In 2024, the PKK carried out 218 remote attacks against Turkish forces — a notable increase from 55 in 2018 but marginal in contrast to Turkey’s 4,593 attacks against PKK targets the same year. This growing asymmetry reflects a shift in the balance of power and may have influenced the PKK’s recent move to disarm and seek political alternatives.

Why has Turkey re-engaged now?

President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan is facing growing domestic unpopularity amid an increasingly emboldened opposition. This dissent was reflected in the 2024 local elections, where the ruling AKP, or Justice and Development Party, lost key municipal councils. Against this backdrop, Erdoğan re-engaged the Kurdish question by reopening indirect contact with Öcalan. This re-engagement appears designed to undercut Kurdish support for the opposition and secure the parliamentary majority needed for constitutional reform that would allow Erdoğan to run again in 2028.3The New Arab, “Turkey’s Erdogan meets pro-Kurdish politicians as they seek to end a 40-year conflict,” 10 April 2025. The government allowed several visits to İmralı prison to visit Öcalan by intermediaries in early 2025, which paved the way for Öcalan’s February call for the PKK to disband.

Since the decision to disband, Turkish officials have stated they are closely monitoring the process to ensure it is not derailed.4Gavin Blackburn, “Turkey monitoring situation after PKK announces disbandment, official says,” Euronews, 13 May 2025. No formal roadmap has been published, but reports suggest a disarmament plan coordinated with the Kurdistan Regional Government in Iraq and possibly international stakeholders.5Daren Butler and Jonathan Spicer, “Turkey and PKK face a tricky path determining how militants will disband,” Reuters, 13 May 2025.

While the PKK maintains ties with Kurdish armed groups in Syria, the current disbandment and negotiations are rooted in Turkey’s domestic politics and are not directly linked to the situation in Syria. That said, the broader regional context remains relevant: Kurdish groups in Syria — particularly the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) — have recently moved closer to the Syrian government amid shifting power dynamics following the fall of the Assad regime. While this intra-Kurdish and regional repositioning is not part of the PKK-Turkey discussions, it adds a layer of strategic recalibration that may influence future dynamics.

What will shape the next phase — and what uncertainties remain?

ACLED data show only six remote attacks carried out by the PKK between the group’s unilaterally declared ceasefire on 1 March and 16 May, the latest date of available data. Meanwhile, Turkish operations continued with 968 incidents over the same period. The two sides have also clashed 44 times — the latest incident on 9 May. The last recorded Turkish strike took place on 10 May, and no incidents have been recorded since the PKK decided to disband two days later. Still, Turkey’s military has declared it will continue operations until all threats are cleared, particularly in northern Iraq, where the PKK maintains rear bases. Meanwhile, the PKK has rejected exile for its members and demanded legal guarantees for their reintegration, improved prison conditions for Öcalan, and recognition of Kurdish rights.

Turkey has yet to announce any political or legal concessions. At the same time, Kurdish political actors continue to face repression. Since 2015, dozens of Kurdish figures have been dismissed and thousands of activists detained.6Kurdistan 24, “Eleven thousand pro-Kurdish party members arrested in Turkey: HDP,” 14 November 2018. Without a clear legal framework, the peace process remains fragile. Past efforts suggest that a lack of reciprocity often triggers renewed violence. The disbandment is unprecedented and promising — but how Ankara proceeds will determine whether the process leads to a durable peace or another cycle of collapse.