The incidents in which Russia’s covert involvement is strongly suspected have prompted much interest recently.1U.S. Helsinki Commission, “Spotlight on the Shadow War: Inside Russia’s Attacks on NATO Territory,” 12 December 2024; Benedicte Dobbinga, “Research: Europe increasingly targeted by Russian sabotage,” 20 January 2025; Seth G. Jones, “Russia’s Shadow War Against the West,” Center for Strategic & International Studies, 18 March 2025; Investigative Journalism Network, “Playing With Fire,” European Broadcasting Union, 12 March 2025; Emma Burrows, “Western officials say Russia is behind a campaign of sabotage across Europe. This AP map shows it,” The Associated Press, 21 March 2025 ACLED strives to contribute to the discussion with a regularly updated public dataset mapping such activity leading to confirmed physical damage or significant disruption in Europe, as well as suspicious surveillance of sensitive sites. To facilitate user access to these events, ACLED has been applying a “suspected Russian activity” tag to relevant events since the beginning of Russia’s all-out invasion of Ukraine in 2022. The tag can be found in the tags column of the dataset. The tag does not imply attribution to Russia or Russia-linked actors — rather, the events list suspected perpetrators as unidentified armed groups or civilians as per the ACLED coding guidelines.

The purpose of the tag is to track instances of suspected Russian hostile activity across Europe, the South Caucasus, and Central Asia. Suspected Russian hostile activities include, but are not limited to, targeting and hostile monitoring of both public and military infrastructure supporting Ukraine, disrupting services and operations in countries supporting Ukraine, and targeting Russian exile groups in Europe. The tag is applied to an event only when at least one credible source is reporting suspected Russian involvement. ACLED researchers do not make assumptions themselves on whether they suspect Russia might be involved. The tag is not applied to events for which Russia is clearly identified as the perpetrator, and Russian state actors are coded. To include the latter events in an analysis of suspected and attributed activity, one should parse actor columns for Russian state actors in addition to events filtered through the tag.

On 26 September 2022, four blasts occurred on the Nord Stream 1 and 2 pipelines that used to pump Russian natural gas to Europe, leaving only one of the four pipes intact. European officials suspected the involvement of Russia,2The Economist, “How does underwater sabotage work?” 29 September 2022 which by then had halted supplies in an attempt to strong-arm European Union countries to ease sanctions related to its ongoing invasion of Ukraine. Only a year later was it revealed that the sabotage of Nord Stream may have been the result of a Ukrainian operation, likely an attempt to make it difficult for Russia to resume deliveries of natural gas to Europe. A Ukrainian attack on the TurkStream pipeline that runs from Russia to Turkey was also allegedly considered but not carried out, according to international security sources.3Liliana Botnariuc et al., “All the Evidence Points To Kyiv,” Spiegel, 26 August 2023; Jörg Diehl et al., “How a Ukrainian secret commando blew up Nord Stream,” Spiegel, 20 November 2024 (German) The Nord Stream incident points to the lack of protection and surveillance of critical infrastructure and underscores the difficulty of attributing responsibility for sabotage.4Greg Miller, Robyn Dixon, and Isaac Stanley-Becker, “Accidents, not Russian sabotage, behind undersea cable damage, officials say,” The Washington Post, 19 January 2025

The attack on the Nord Stream pipelines was followed by a string of incidents beginning in October 2023 that damaged European underwater infrastructure in the Baltic Sea, primarily by means of anchor-dragging that cannot be explained by choppy waters or crew ineptitude alone.5Richard Milne et al., “Inside Russia’s shadow war in the Baltics,” Financial Times, 10 March 2025 Russia denies involvement,6EUvsDisInfo, “Underwater incidents, above-water lies,” 4 February 2025 but persistent incidents at sea occur against the backdrop of proliferating suspicious events across Europe that law enforcement agencies suspect could have been orchestrated by Russia. Policy responses in Europe and beyond further corroborate the plausibility of the suspicion.

What appears to be a Russian campaign targeting NATO allies in Europe is reminiscent of the deniable tactics Moscow used before its covert invasion of Ukraine’s Donbas region.7Andrey Zakharov, “His War,” Proekt, 28 November 2023 It is also not entirely new. Russia’s covert operations stem from the “active measures” taken during the Soviet era,8Mark Galeotti, “Active Measures: Russia’s Covert Geopolitical Operations,” George C. Marshall European Center for Security Studies, June 2019 which combined deniable sabotage and influence operations. It was resuscitated in the modern “Gerasimov doctrine” on hybrid warfare, which outlines a strategy of covert and deniable attacks on Russia’s adversaries short of prompting armed response.9Mark Galeotti, “The ‘Gerasimov Doctrine’ and Russian Non-Linear War,” In Moscow’s Shadow, 6 July 2014 These operations stop short of triggering mutual defense clauses and include recently ramped-up mis- and disinformation campaigns,10European External Action Service, “3rd EEAS Report on Foreign Information Manipulation and Interference Threats,” 19 March 2025 interference in elections to install malleable counterparts,11Oana Popescu-Zamfir, “Russian Interference: Coming Soon to an Election Near You,” Carnegie Europe, 13 February 2025 and encouraging irregular migration in the EU to fuel the ascendance of nativist political forces.12The Economist, “The hard right is getting closer to power all over Europe,” 14 September 2023 The tug of war in the cyber domain is another important dimension,13Center for Strategic & International Studies, “Significant Cyber Incidents,” accessed on 22 April 2025 with frequent attacks on public services. For instance, in 2024, cyber attacks tracked to Russia-linked perpetrators disrupted hospital operations in Romania and the United Kingdom.

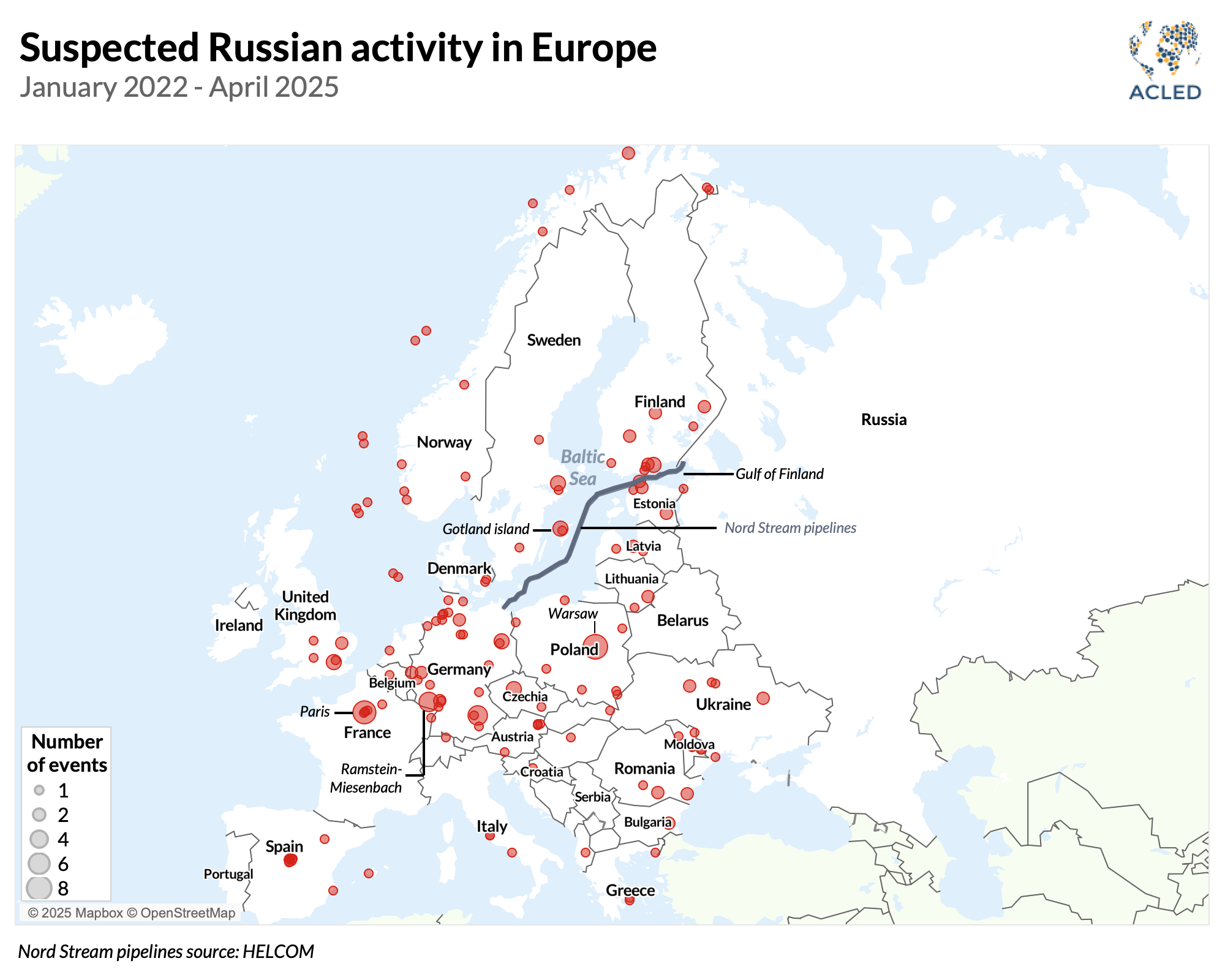

The scope of this report, however, is limited to incidents that inflicted physical damage and caused significant disruption. It maps 190 events since 2022 (see tables and map below), detailing activity that is not directly attributed to Russia but in which Russia’s covert and increasingly reckless efforts to undermine Europe’s support for Ukraine are suspected. They mostly target countries involved in helping Ukraine’s self-defense and expose the vulnerability of Europe’s own infrastructure, while also sowing chaos on the streets. ACLED notes a concentration of suspicious events in the Baltic Sea area, possibly due to the rushed accessions of Finland and Sweden to NATO. The resulting extension of the NATO land and maritime border with Russia may lead it to respond by probing the defenses on the Alliance’s eastern flank.

| Suspected Russian activity across Europe January 2022 – April 2025 |

|

|---|---|

| Country | Incidents |

| Germany | 39 |

| Norway | 19 |

| Finland | 17 |

| Poland | 16 |

| France | 13 |

| Spain | 11 |

| Sweden | 10 |

| United Kingdom | 8 |

| Others* | 57 |

| Total | 190 |

* Includes Ukraine, Moldova, Estonia, Romania, Czech Republic, Austria, Lithuania, Latvia, Italy, Greece, Bulgaria, Slovakia, Netherlands, Hungary, Denmark, Croatia, Belgium, and Albania.

| Suspected Russian activity across Europe January 2022 – April 2025 |

|

|---|---|

| Type of activity | Incidents |

| Drone overflight | 59 |

| Sabotage | 45 |

| Spying | 15 |

| Vandalism | 13 |

| Arson | 12 |

| Bloody parcel | 9 |

| Attack | 7 |

| Jamming | 6 |

| Flammable parcel | 6 |

| Cyberattack | 6 |

| Other | 12 |

| Total | 190 |

Punishment for supporting Ukraine

Since the start of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, European countries pledged over 100 billion euros in military aid to Ukraine.14A. Antezza et al., “Ukraine Support Tracker Data,” Kiel Institute, April 2025 In addition, these countries host transit routes as well as logistics and training hubs, helping Ukraine fend off Russian aggression. Coupled with EU sanctions on Russia, siding with Ukraine renders Europe a target of Russian retribution.15Alexander Gabuev, “Russia is trying to put a price tag on Nato’s involvement in Ukraine,” Financial Times, 7 July 2024

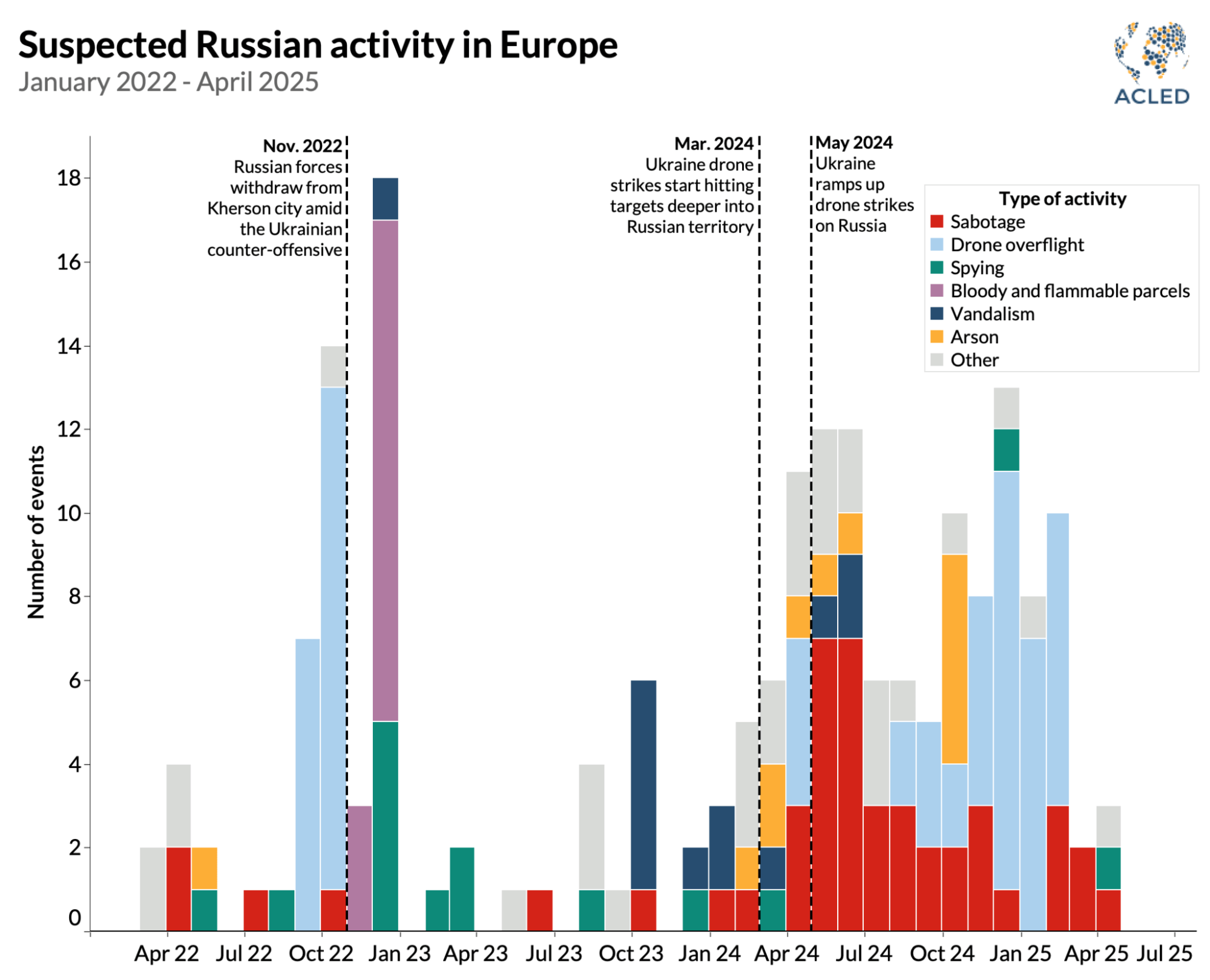

In the early stages of the invasion in 2022 and amid mass expulsions of Russian diplomats suspected of moonlighting as intelligence operatives in Europe, ACLED data show 10 instances of possible Russia-linked activity, including the torching of clothing aid collected by the Ukrainian embassy in Athens in May and a blast at an arms depot in Bulgaria in July. An outburst of suspected Russian activity in Europe beyond amateur surveillance of sensitive sites occurred in late November and December, after the Russian army was first routed in Ukraine’s Kharkiv region and then forced to withdraw from Kherson city (see graph below). The spate of activity included at least six flammable parcels sent to Spanish government officials, an arms producer in Spain, and Ukrainian and United States diplomats posted to Spain, as well as at least nine parcels containing animal parts and blood sent to Ukrainian diplomatic missions across Europe.

Likewise, 2023 appears to have been relatively calm as Russia gained confidence on the battlefield after fending off a Ukrainian counter-offensive and relaunching its ongoing assault on the Donetsk region. Mid-year, a series of explosions occurred at the same arms depot in Bulgaria — days after Bulgaria announced its intent to send ammunition to Ukraine.16Victor Jack and Jacopo Barigazzi, “Bulgaria wants to join the EU’s ammo-for-Ukraine club,” Politico, 25 June 2023 In August, the spoofing of radio signals disrupted rail traffic in Poland after Polish authorities detained nine people suspected of setting up a surveillance network to track rail shipments of weapons to Ukraine.

The tide may have turned in 2024. ACLED data show that more than half of all suspicious events since February 2022 occurred in 2024. Around 35% of these events were sabotage, and another 27% were unauthorized drone overflights. During the year, Russia’s steamroller offensive secured only incremental gains in Ukraine but incurred staggering losses of personnel.17Meduza, “Three years of death,” 24 February 2025 Meanwhile, Ukrainian drones wreaked havoc on Russia’s oil installations, reaching targets as far afield as the Ural mountains.

These developments may have prompted Russia to ramp up deniable attacks on Europe’s defense industry, which was only occasionally targeted in the previous decade.18Michael Weiss, Christo Grozev, and Roman Dobrokhotov, “Exclusive: Inside an Infamous Russian Spy Unit’s First Bombing in NATO,” The Insider, 20 October 2023 In February, the US and Germany called out a Russian plot to assassinate the head of Rheinmetall, Armin Papperger, an arms producer involved in supplying the Ukrainian army and opening assembly sites in Ukraine. In May, a fire at another weapons producer — a Diehl factory near Berlin — destroyed four floors and caused partial collapse of the building. German authorities, citing communications intercepts, attributed the incident to Russian sabotage.19Bojan Pancevski, “Russian Saboteurs Behind Arson Attack at German Factory,” The Wall Street Journal, 23 June 2024

Civilian or probable dual-use targets also faced an increased threat of sabotage, with attacks becoming more reckless. Between March and May 2024, suspected Belarusian and Ukrainian recruits of Russian agents set ablaze three warehouses in Lithuania, Spain, and the UK, as well as a shopping mall in Poland. In July, three explosions involving flammable parcels occurred at warehouses in Germany, Poland, and the UK, with a fourth attempt foiled.20Anna Koper et al., “Insight: Sex toys and exploding cosmetics: anatomy of a ‘hybrid war’ on the West,” Reuters, 15 April 2025 The incidents prompted alleged US backchannelling with Russia, according to The New York Times, to dissuade further attempts to send flammable parcels across the Atlantic due to the risk of mid-air explosions.21David E. Sanger, “Biden Aides Warned Putin as Russia’s Shadow War Threatened Air Disaster,” The New York Times, 13 January 2025

Furthermore, military sites became increasingly targeted. At the end of May, a cache of explosives was discovered at a pipeline hub supplying military bases in Germany’s Bellheim municipality. In August, security breaches occurred at two military bases in Germany’s Nordrhein-Westfalen, prompting concerns about water contamination at and around them. In addition, between August 2024 and February 2025, ACLED records about 20 sightings of unidentified drones hovering over military bases or warships in or near Germany and the UK. Similar incidents occurred on at least two occasions near Romania’s Mihail Kogalniceanu airbase in April 2024. Facilities in Germany, Poland, and Romania are extensively used for supplying, training, and coordinating Ukrainian armed forces.22Adam Entous, “The Partnership: The Secret History of the War in Ukraine,” The New York Times, 29 March 2025

The Baltic Sea in crosshairs

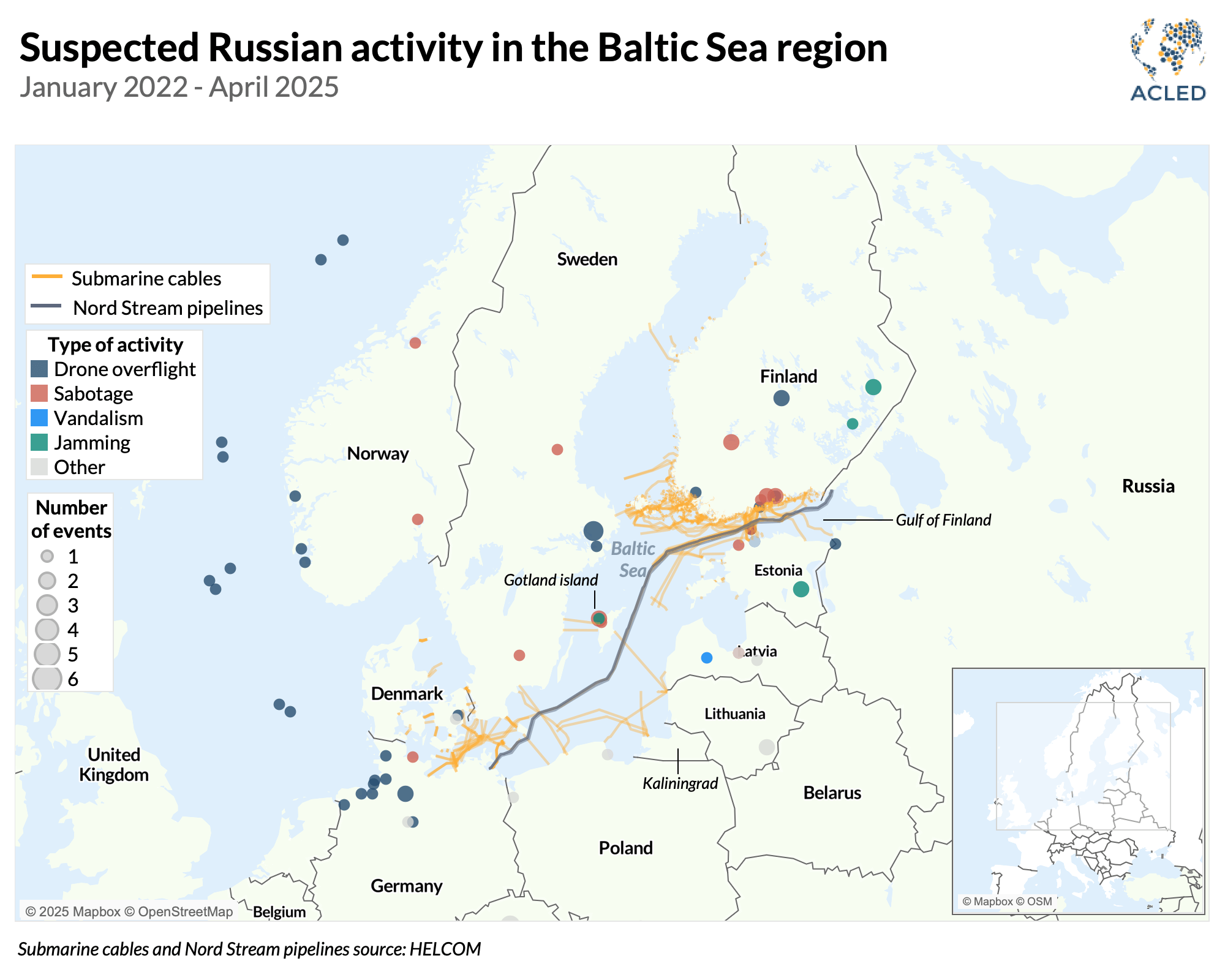

On 7 October 2023, a vessel registered in China cut two telecommunications cables in the Baltic Sea connecting Estonia to Finland and Sweden and broke a natural gas pipeline linking Finland and Estonia. Four similar incidents occurred in late 2024 and early 2025, three near Sweden’s strategic Gotland island,23Natasha Lindstaedt, “Putin’s designs on a Baltic island are leading Sweden to prepare for war,” Conversation, 24 May 2024 and affected telecoms, power, and gas lines connecting Nordic countries, the Baltic states, and Germany. None of the ongoing investigations have so far proved ill intent,24Greg Miller, Robyn Dixon, and Isaac Stanley-Becker, “Accidents, not Russian sabotage, behind undersea cable damage, officials say,” The Washington Post, 19 January 2025; Alexander Martin, “European officials increasingly certain Baltic Sea cable breaks are accidental, not sabotage,” The Record, 27 March 2025 although some of the cargo ships suspected of sabotage are part of Russia’s so-called shadow fleet — often run-down ships used to circumvent the G7 and Australia’s price cap on Russia’s oil.25Reid Standish, “Baltic Sea Incidents Put Spotlight On Russia’s ‘Shadow’ Fleet,” Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, 29 January 2025 The existence within Russian military intelligence of a dedicated unit tracking subsea infrastructure further corroborates the suspicion.26Jim Sciutto, “Exclusive: US sees increasing risk of Russian ‘sabotage’ of key undersea cables by secretive military unit,” CNN, 6 September 2024

Incidents targeting Europe’s infrastructure do not appear to be meant to cause significant disruption but rather point to its vulnerability to outside interference. The persistence of such incidents and their concentration in the highly contested Baltic Sea area leaves room for concerns about a deliberate campaign. Russia cited NATO’s actual and perceived eastward expansion as a rationale for invading Ukraine.27Paul Kirby, “Why did Putin’s Russia invade Ukraine?” BBC, 21 April 2025 The accession of hitherto neutral Finland and Sweden to NATO in 2023 and 2024 in response to the invasion extended Russia’s land and maritime border with the alliance by hundreds of kilometers. It further isolated Russia’s Kaliningrad exclave, which is believed to serve as a hub for organizing covert operations targeting neighboring countries.28Mindaugas Aušra and Indrė Makaraitytė, “International investigation: Russian special forces change tactics in the Baltics,” LRT, 30 October 2024 Rising tensions and rapid re-militarization of the Baltic Sea by both sides29The Associated Press, “NATO holds its biggest exercises in decades next week, involving around 90,000 personnel,” 19 January 2024; Pavel Luzin, “Russia Reorganizes Military Districts,” Jamestown Foundation, 29 February 2024; Thomas Grove, “The Russian Military Moves That Have Europe on Edge,” The Wall Street Journal, 27 April 2025 may be prompting Russia’s interest in surveilling infrastructure in shoreline countries and elsewhere in Europe, possibly to probe its susceptibility to sabotage.

Rival militaries in close proximity are involved in numerous incidents that could lead to an escalation if something goes wrong. These are difficult to quantify, as only a fraction of these occurrences are known to the public. Reported ones nonetheless point to an increasingly contested space in and around the Baltic Sea (see map below). For instance, in late 2024 and early 2025, the Russian military harassed German and French airborne patrols over the Baltic Sea near Kaliningrad by firing emergency flares in one instance and locking in an air defense system in another. NATO allies’ jets have scrambled to respond to unannounced or suspicious Russian activity in the air practically on a daily basis since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, though the frequency has declined since 2022.30Rudy Ruitenberg, “NATO intercepts of Russian aircraft stable in 2024 over prior year,” Defense News, 13 January 2025

Another indicator of rising tensions is GPS signal interference affecting civilian aircraft in the Baltic Sea area. In 2024, ACLED records at least four reports of persistent jamming preventing the landing of passenger planes, mostly in Finland but also in Estonia. In addition, Russia is believed to have jammed the then British defense secretary’s plane when it was flying near Kaliningrad in March 2024.31Mabel Banfield-Nwachi, “Russia suspected of jamming GPS signal on aircraft carrying Grant Shapps,” The Guardian, 14 March 2024 The need to blunt incoming Ukrainian drones targeting Russia’s oil infrastructure, including in the nearby Russian Leningrad region, provides only a partial explanation, given that at least two similar incidents occurred in 2022, when Ukraine had not yet acquired long-range drone capacity. Furthermore, GPS signal interference also affects maritime traffic, and it is likely that some jamming has possibly been conducted off the shadow fleet vessels.32Anne Kauranen, “Finland detects satellite navigation jamming and spoofing in Baltic Sea,” Reuters, 31 October 2024

Furthermore, the addition of the two Nordic members to NATO and soaring tensions in the Baltic Sea may explain the correlation with the increased frequency of unauthorized surveillance of infrastructure in northern Europe. Since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, ACLED records almost 40 instances of unidentified drones overflying infrastructure sites in northern Europe, of which around half occurred in September and October 2022 alone, mainly in Norway’s territorial waters over sensitive energy installations and in Finland over critical infrastructure. After a lull in 2023, possible Russia-linked drones returned in August 2024. Seven of nine sightings between then and February 2025 occurred in northwestern Germany over energy and port infrastructure and sensitive production sites. Notably, the drone sightings were concomitant with sabotage scares and drone overflights at or over military sites across Germany in August and December 2024. The proximity of most sightings to the sea suggests that the drones may have been launched from military or commercial vessels.

The persistence of attempts to sabotage the water supply and treatment infrastructure in Europe is particularly concerning. In May and June 2024, ACLED records at least seven attempts to tamper with equipment at water installations at five locations in Finland. Two similar incidents occurred in Sweden in October 2024 and March 2025, the latter probably the most serious to date, as unidentified perpetrators damaged a water supply cable on Gotland, threatening the interruption of running water on the island. In addition, cyber attacks by Russia-linked hackers targeted water infrastructure in France in March 2024 and in Denmark in December 2024. This happened against the backdrop of intelligence services’ public warnings about Russia-linked actors’ attempts to remotely sabotage Europe’s power grid and rail service.33Sam Clark, “Winter is coming. So are Russia’s elite hackers,” Politico, 22 November 2024; Alice Hancock, “Russia is trying to sabotage European railways, warns Prague,” Financial Times, 5 April 2024

Sowing chaos in Europe

Deniability is the core feature of suspected Russian activity across Europe. Although some events could be catalogued as mere vandalism, their significance and potential for disruption should not be underestimated. Meanwhile, Russia may exploit the cover of local militancy to stage attacks and sow chaos with plausible deniability, further blurring the lines and complicating investigations.

Between 26 and 30 October 2023, stencilled blue Stars of David appeared in the greater Paris area. Occurring at the height of Israel’s offensive in Gaza, the graffiti incidents could hardly be seen as conducive to interfaith comity amid rising hate crimes in a country populated by sizable Jewish and Muslim communities.34Samuel Petrequin, “Antisemitic acts have risen sharply in Belgium and France since the Israel-Hamas war began,” The Associated Press, 25 January 2024 The inflammatory street art was traced back to a Moldovan couple acting at the behest of a Russia-linked Moldovan businessman. Similar vandalism occurred in Paris in the run-up to the 2024 Olympic Games and included the desecration of a Holocaust memorial site, graffiti warning of the imminent collapse of balconies in the Notre-Dame Cathedral area, and stencils of coffins with the text “French soldier in Ukraine” spray-painted on walls. Additionally, actual coffins draped in French flags and inscribed with the same text were left at the Eiffel Tower. The suspected Moldovan and Bulgarian perpetrators, however, may have aimed for the graffiti to reach a wider audience than the crowds descending on the French capital. In all instances, they sought to amplify the messages on social media as well.35Damien Leloup, “Star of David graffiti in Paris linked to other interference operations in Europe,” Le Monde, 15 August 2024 Security concerns ahead of the Olympics reached a fever pitch with the arrest of a Donetsk native who accidentally detonated explosives while making a bomb in a hotel room in a Paris suburb in June, along with the arrest of an operative of the Russian Federal Security Service, or FSB, on charges of plotting to disrupt the opening ceremony in July. The latter apparently fell victim to his own partiality to drink and boast.36Roman Dobrokhotov, Michael Weiss, and Christo Grozev, “Michelin Red Star: The Insider reveals identity of arrested Russian chef-agent who planned ‘destabilizing’ acts at Paris Olympic Games,” The Insider, 25 July 2024

Despite French and allied authorities’ best efforts to avoid major incidents, serious disruption nonetheless did occur around the Olympic Games. On the eve of the opening ceremony on 26 July, unidentified perpetrators set fire to railway line cables north, east, and southwest of Paris, severely disrupting high-speed rail traffic from and to the capital for three days. A smaller-scale coordinated attack on infrastructure occurred on 29 July, targeting the country’s fiber-optic networks and affecting at least 17 of 96 French mainland departments. In both instances, far-left groups claimed responsibility, citing dissatisfaction with capitalism, nuclear waste management, and the government’s response to the New Caledonia riots occurring at the time. Despite the likelihood of homegrown militant activism, French authorities did not rule out Russia’s possible involvement in the incidents.37Elsa Conesa et al., “In Europe, acts of sabotage using explosives attributed to Russia,” Le Monde, 18 October 2024 (French)

The French case suggests that the room for deniability may be expanding and cutting both ways. Months ahead of the revelation of the alleged Russian plot to assassinate Rheinmetall boss Papperger, suspected far-left activists attempted to set ablaze the arms manufacturer’s second home over his support for Ukraine.38James Rothwell, “Arsonists attack home owned by chief of leading German arms manufacturer over Ukraine links,” The Telegraph, 1 May 2024 Europe’s pivot toward greater defense spending and away from enforcing stricter environmental policy may prompt increased activity among concerned groups and individuals, complicating investigations that may be looking for a non-existent Russian footprint. Meanwhile, increasing polarization may be a boon for Russian recruiters who increasingly rely on local criminals, militant activists, and destitute migrants — including Ukrainian refugees — to carry out operations.39Carina Huppertz et al., “Make a Molotov Cocktail’: How Europeans Are Recruited Through Telegram to Commit Sabotage, Arson, and Murder,” Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project, 26 September 2024 The amateurization of sabotage may increase the probability of collateral victims, including the presumed perpetrators themselves, and is mirroring the shadow war between Russia and Ukraine, where arson and bombing attempts by unwitting perpetrators duped over the phone or online have been common since 2023.

Bracing for what’s next

Incidents across Europe in which Russian involvement is suspected appeared to wane by March 2025, especially compared to the peak observed in late 2024 and early 2025, when the standoff between Russia and Ukraine’s backers was most acute. The second Trump administration’s overtures toward Russia may have contributed to the latter hitting the brakes on covert operations in Europe to explore the possibility of forcing Ukraine to capitulate during negotiations rather than in an increasingly costly all-out war. The outcome of roller-coaster talks to end the fighting in Ukraine is unpredictable, and the high odds of the US leaving Ukraine and Europe to their own devices in dealing with an aggressive Russia may mean that the lull in sabotage attempts may be only temporary.

NATO allies have been careful not to overreact to covert Russian operations, despite the growing suspicious activity.40Deborah Haynes, “Unconventional Russian attack could cause ‘substantial’ casualties, top NATO official warns,” Sky, 30 December 2024 A low-key response is underway nevertheless, especially in the Baltic Sea area, where NATO increased patrolling, including with naval drones.41NATO Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe, “Baltic Sentry to enhance NATO’s presence in the Baltic Sea,” 14 January 2025; The Economist, “NATO’s race against Russia to rearm,” 12 March 2025 It also launched a dedicated unit to ensure the security of undersea infrastructure.42NATO, “NATO officially launches new Maritime Centre for Security of Critical Undersea Infrastructure,” 28 May 2024 Attempts to hold perpetrators accountable for damage to infrastructure in the Baltic Sea have not borne fruit, however, despite several vessel seizures and crew arrests. International sea navigation law’s priority on unhindered passage may be precluding bolder action.43Rikard Jozwiak, “How To Protect The Baltic Sea From The Russian Shadow Fleet,” Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, 25 February 2025 Beyond the actions taken in the Baltic Sea, the targets of suspected Russian activity respond where they can. Polish authorities shut down the Russian consulate in Poznan in late 2024, citing its involvement in coordinating sabotage attempts in the country, and another in Krakow in May 2025 in response to the Warsaw shopping mall fire.44The Associated Press, “Poland alleges Russian sabotage and is closing one of Moscow’s consulates,” 22 October 2024; Vanessa Gera, “Poland orders closure of Russian consulate in Krakow, citing arson attack blamed on Moscow,” The Associated Press, 12 May 2025 Finland has kept its land crossings with Russia shut for over a year due to the flow of asylum-seekers from poorer countries.45Essi Lehto, “Finland to keep Russia border closed until further notice,” Reuters, 16 April 2025

The Baltic States may face a greater risk of an escalation from their eastern neighbor than others in Europe. If Russia is allowed to get away with yet another land grab in Ukraine, it may attempt to test the validity of mutual defense clauses amid waning interest from the US in defending its allies in Europe. Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania — all three former Russian and Soviet dominions — have been the focus of Russian media and diplomatic narratives alleging the discrimination of Russian-speaking populations for most of their independence since 1991. This is even longer than Ukraine, which has been subjected to a similar informational policy since the Orange Revolution in 2004. Possible, though not exhaustive, scenarios replicating Russian covert and then all-out invasions of Ukraine since 2014 may include another “special operation” to “liberate” Russian speakers in Estonia’s Narva just across the eponymous river that serves as a border or the seizure of the Suwałki gap, sandwiched between Lithuania and Poland, to gain a land link to Kaliningrad. This would echo the occupation of southern Ukraine to acquire a land corridor to the annexed Crimean peninsula.

However outlandish these possibilities may seem, the countries concerned appear to take them seriously — all EU states bordering Russia announced plans to leave the Ottawa Convention banning the use of anti-personnel mines, citing the need to improve defenses.46Vincenzo Genovese, “EU countries’ withdrawal from anti-landmine convention sparks controversy,” Euronews, 10 April 2025 A major test of wills and capabilities may occur as early as September 2025 when Belarus is scheduled to host another iteration of the joint Russian-Belarusian “Zapad” drill.47Belta, “Lukashenko explains details of forthcoming Belarusian-Russian army exercise Zapad 2025,” 10 April 2025 The drill in late 2021 was used to justify the build-up of Russian forces along Ukraine’s border with Belarus, which Russian forces used to attempt a decapitating attack on Kyiv.

Even if the worst fears may prove overblown, European countries will have to reckon with the need to invest in efforts to foil sabotage attempts on both land and at sea and protect critical infrastructure. With the US apparently disengaging from the region and viewing Russia as less of a threat,48Erin Banco and Mari Saito, “Exclusive: US suspends some efforts to counter Russian sabotage as Trump moves closer to Putin,” Reuters, 19 March 2025 Europe may have to make do without the US intelligence and law enforcement support that helped foil the excesses of suspected Russian activity, such as assassination attempts and flammable parcels onboard planes. Europe may not have much time to prepare for another possible wave of Russian attempts to test its resolve to stand by Ukraine and ultimately defend itself.

Visuals produced by Ciro Murillo.