Clionadh’s Monthly ACLED Data & Analysis Outlook

I have been grappling with two distinct questions these last few months: the first being, “How is conflict changing?” and the second, “What direction is it going in?”

This latest reflection was spurred by three episodes in particular: the Kurdish PKK deciding that their conflict had run its course, the India-Pakistan détente, and the shift in Syria. Whereas many people ask what stops conflict, in all three cases, power was the determining factor (and that Turkey’s Recep Tayyip Erdoğan is one crafty fellow). The plain reality to the Kurds was that they had lost the battle in Turkey. In India and Pakistan, the leverage of the international community prevailed on domestic hotheads for now, and in Syria, again, the reality that someone needs to be in charge, and relieving sanctions was the main sign of international acceptance for the facially fortunate new leader,1I think in “Trump translation”, “attractive” means tall with good posture. He says “good looking” when he likes a face, subtlety not being a strength of his. Ahmed al-Sharaa. (I would like to point out that way too many American positions on domestic or international politics seem to come down to whether someone has a nice face. Remember Luigi Mangione? These reactions are widely shared across American political beliefs and by 13-year-olds the world over.)

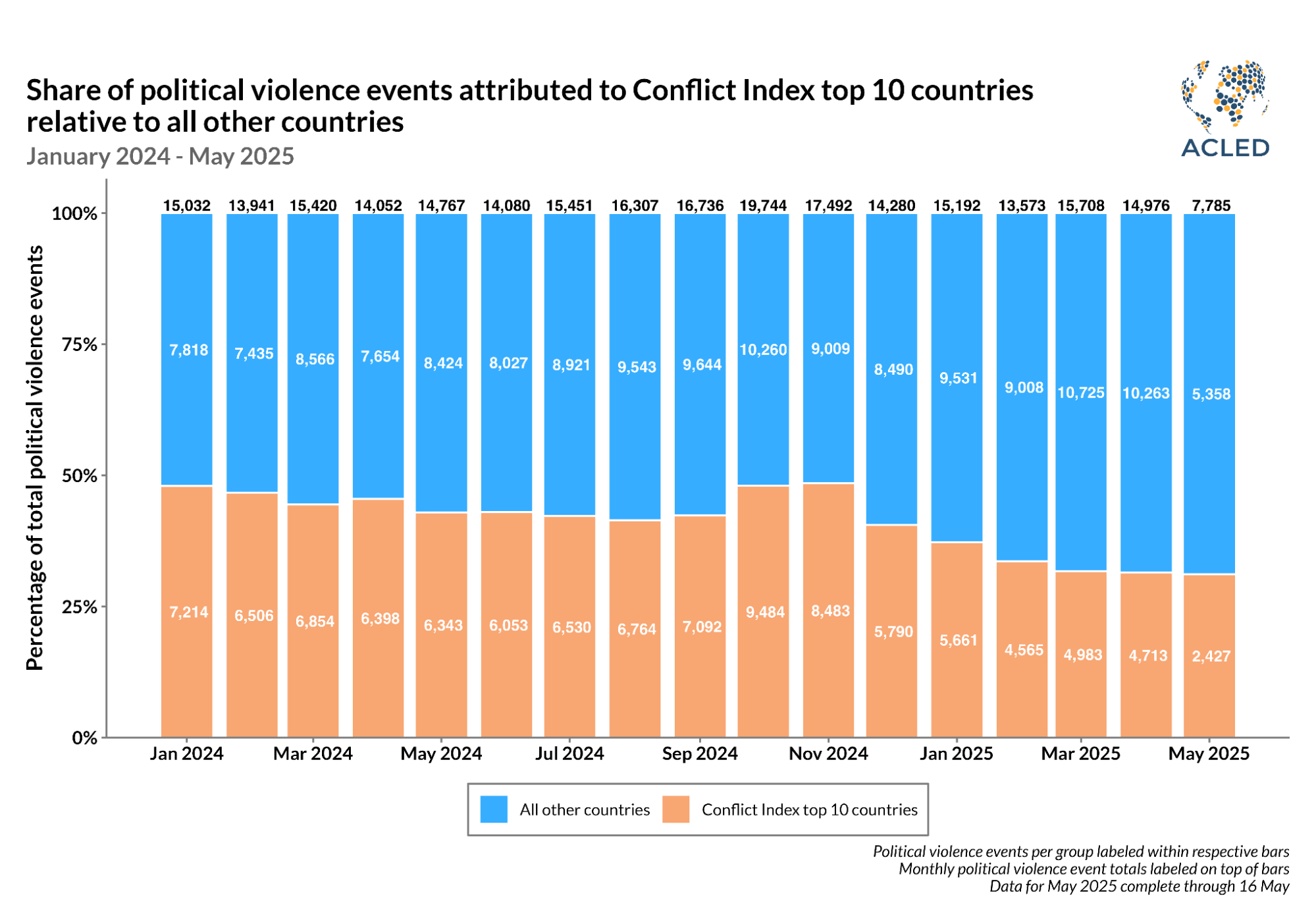

The new United States administration has claimed credit for a lot of changing conflicts (e.g., Yemen, Ukraine, etc.). In fairness, over the past five years, conflict rates doubled, and this does not speak well of the Biden administration. Has the world now broken out into peace? No, but since the beginning of the year (…so caveats for a limited pattern), total rates of political violence decreased from a peak in late 2024 (closer to 20,000 events per month) to about 15,000 events per month (the figure does not include all of May’s data). This is roughly in line with the early 2024 variation. Violence rates not only increase during the year, but information comes in from local sources that can be checked and included throughout the year, and this accounts for some of the change. What is important here is that the share of political violence attributed to ACLED’s combined top 10 Conflict Index countries has also decreased and is steadily below the norm for these countries throughout 2024. Specifically, there have been large drops in Syria, Lebanon, Brazil, and Sudan. But these patterns are not consistent: Colombia increased, as did Mexico, and Brazil’s decline is very recent. What is clear to me is that these conflict environments are reacting to domestic and international shifts. How conflict creates and responds to shifts in power is something that we don’t give enough time to in analysis.

This ebb and flow is found across active conflicts despite differences in the agenda of these violent groups. One of the features of the ACLED Conflict Index that is most informative compared to others is that it showcases how a range of countries and very different conflict forms can have similar extreme rates of actual violence. Typically, in indices, Sudan’s conflict would not be compared with Mexico’s. But why not? The amount of conflict is similar, the proportion of the population exposed to violence is similar, the deaths from conflict are similar, as are the number of armed groups. What differs is our expectation of both countries, rather than the lived reality of the conflict. Conflicts take on the shape and scale that is most likely to be successful in situ, and successful groups must react to changes for the same reason.

Did we expect these shifts in the early months of the Trump administration? Continuity is the default assumption rather than shifts, and a lot of conflict analysis consists of a) admiring the complexity of the problem; b) refusing to acknowledge that “no conflict” isn’t a viable or desired option; and c) misrepresenting why the conflict occurs in the first place. We are badly served by a bias toward inaction and expecting continuity. Instead, across the world, there is now a “bias toward action.” A lot of things are happening — so, is it better?

First, I would caution that any decline has been met with a sustained or increased level of conflict in countries that are not currently “extremely violent.” A lot of leaders, armed groups, and aspiring warlords are observing the new distribution of power and changing tactics to survive politically. On the domestic level, this can take any number of forms — from jumping on an “anti-colonial” populist message to threatening to kill and replace office holders. Additionally, four international influences are either enhancing or detracting from these efforts: The Trump administration is not seeking less violence but to extend its own leverage at a price; the Gulf/Saudi Arabia are in competition for clients to patron; China wants to build up those who can secure power in 10 years; and Turkey wants to pave the way as the representative of the Global South, its influence, and resources. This new international establishment can collaborate, ally, or oppose each other and their proxies.

All four major international influences share a commonality: They all support conflict “movers.” A conflict mover is a group/elite that can dominate the environment — it can be a government, a coup leader, a warlord, or a politician (never, to the dismay of many, a “people’s movement”). Movers alter the environment toward consolidating power. Power is amoral, non-ethical, and highly biased, and conflict is its main engine (not its only one).

Conflict in any place is shaped by how power consolidation is best accomplished in that space (e.g., in some places it comes from alliances with local groups. In others, rivals must be eliminated and their troops usurped. In still other places, power is consolidated through formal political roles or status, from which elites can organize conflict more efficiently). The strategy of power consolidation varies, but the goal remains the same. The issue becomes more dire when a group can’t control the power flow or the conflicts. In such cases, quite a lot of violence breaks out to find the new consolidation point and person. We are seeing that at the moment in Mexico as the Sinaloa Cartel’s fracturing is leading to rivals exploiting their weakness.

We should expect to see a lot more chancers using conflict and rhetoric that is coded for a specific international audience as well as a domestic one. Power is for the taking at the moment, so there will be takers. As an example, please see the BBC’s embarrassing fangirling of favorite junta leader, Burkina Faso’s Captain Ibrahim Traoré. Traoré knows what he needs to do to consolidate power — and that is to be a symbol of anti-colonialism across the continent. Reducing violence, combating jihadists, and securing the state are not what he is good at. From the BBC: “Traoré’s popularity comes despite the fact that he has failed to fulfil his pledge to quell a 10-year Islamist insurgency that has fuelled ethnic divisions and has now spread to once-peaceful neighbours like Benin. His junta has also cracked down on dissent, including the opposition, media and civil society groups and punished critics, among them medics and magistrates, by sending them to the front-lines of the war against the jihadists.” They then go on to compliment his face.

To summarize this meander: Since the beginning of the year, conflict is slightly down in extremely violent countries but is unlikely to stay at this lower level. Conflict in high-violence countries is up slightly. These moves are all likely to be responses to a very volatile international environment, whereby support and sponsorship of violent political agendas are for the taking. The world is getting increasingly violent. Different areas are experiencing various forms of violence because conflict reflects how power flows in places.

Webinars

How the Sinaloa Cartel rift is redrawing Mexico’s criminal map

On 14 May 2025, ACLED hosted a webinar on how the fallout of the Sinaloa Cartel dispute has set off a broader realignment of criminal groups in Mexico and opened up opportunities for new conflicts in contested territories. In the webinar, which was moderated by ACLED Associate Analysis Manager Daniel Herrera Kelly, we heard from the report’s authors — ACLED Senior Analyst for Latin America & the Caribbean, Sandra Pellegrini, and Mexico, Central America, & the Caribbean Research Manager, Maria Fernanda Arocha — as well as México Evalúa’s Director of Security Programs, Armando Vargas. You can view the webinar recording here. It is an incredible piece!

A perpetual state of war? An analysis of IDF and Palestinian armed group tactics in the West Bank and Gaza

Join ACLED for a live conversation at 15:00 CET on 29 May 2025, during which we will examine the shifting tactics in Israel Defense Forces activity, Palestinian armed groups, and the role that internal Israeli politics are having on violence in the West Bank and Gaza. The webinar follows the publication of ACLED’s recent report, Iron Wall or iron fist? Palestinian militancy and Israel’s campaign to reshape the northern West Bank. Register to attend the webinar here.

Select ACLED in the media!

- Al Jazeera again featured ACLED data in its articles “Animated maps show US-led attacks on Yemen” and “Trump’s 100-day scorecard: Executive orders, tariffs and foreign policy.”

- In a similar vein, the Financial Times used ACLED data in its article “Donald Trump’s bombing campaign against Houthis tests his vow to ‘stop wars.’”

- Insight Crime interviewed Sandra Pellegrini and Maria Fernanda Arocha to discuss ACLED’s report How the Sinaloa Cartel rift is redrawing Mexico’s criminal map.

- ACLED data on Burkina Faso were also featured in The Associated Press.

- The Guardian referenced ACLED’s figures on political violence in Jammu and Kashmir and global conflicts.

- Heni Nsaibia shared his insights on jihadist attacks in Benin with Bloomberg.

- Su Mon was featured in a Reuters article on Myanmar, which was picked up by The Diplomat. Reuters also used ACLED data in an article on the Gaza Strip.

- Nichita Gurcov continued to offer insightful comments on Ukraine and Russia with The Kyiv Independent.

Notes and notions

The second someone says drones, my eyes glaze over, but this was interesting and gave me a new sense of attention and urgency to our upcoming Myanmar report about drones.

Every moment of this video is fascinating — the focus, the rhetoric, and the arguments.

Irish news! Stay clear of Irish airspace if you may have committed war crimes. And in a sign that the state has really changed, this used to be a common claim of almost every child in a big family. Now, it gets people in trouble. One of my sisters still claims she was mixed at birth.

I love this woman and wish everyone had someone like her in their house.

I read Samantha Harvey’s “Orbital” for a book club, and its main attribute is that you can start reading from any page in the book and not lose the thread of the non-story. I am now reading “Butter” by Asako Yuzuki, and it veers from being deeply evocative about butter to murders and misogyny in Japan. It is great. Thanks to Vicky for both suggestions!

If I have spoken with you in past years, you have undoubtedly heard of my unabiding love of camels. This job combines my two interests, and I will be applying (and rejected, I imagine) immediately.

Louis Theroux’s documentary on settlers was excellent and jarring to watch, and I would also recommend a much earlier documentary on the Lagos transport union. We have coded hundreds of events involving those transport union bastards over the years. Watch with the family as children are riveted by it!