Read in Spanish

How unrelenting gang violence has tested the president’s militarized approach

On 24 May, the incumbent right-wing President Daniel Noboa was sworn in in Ecuador, after winning the runoff of the presidential election against leftist Luisa González. Elections were held amid an unprecedented wave of violence linked to organized crime in a country that was once one of the least violent places in Latin America but quickly turned into the region’s murder capital, an infamous title it has held since 2023.

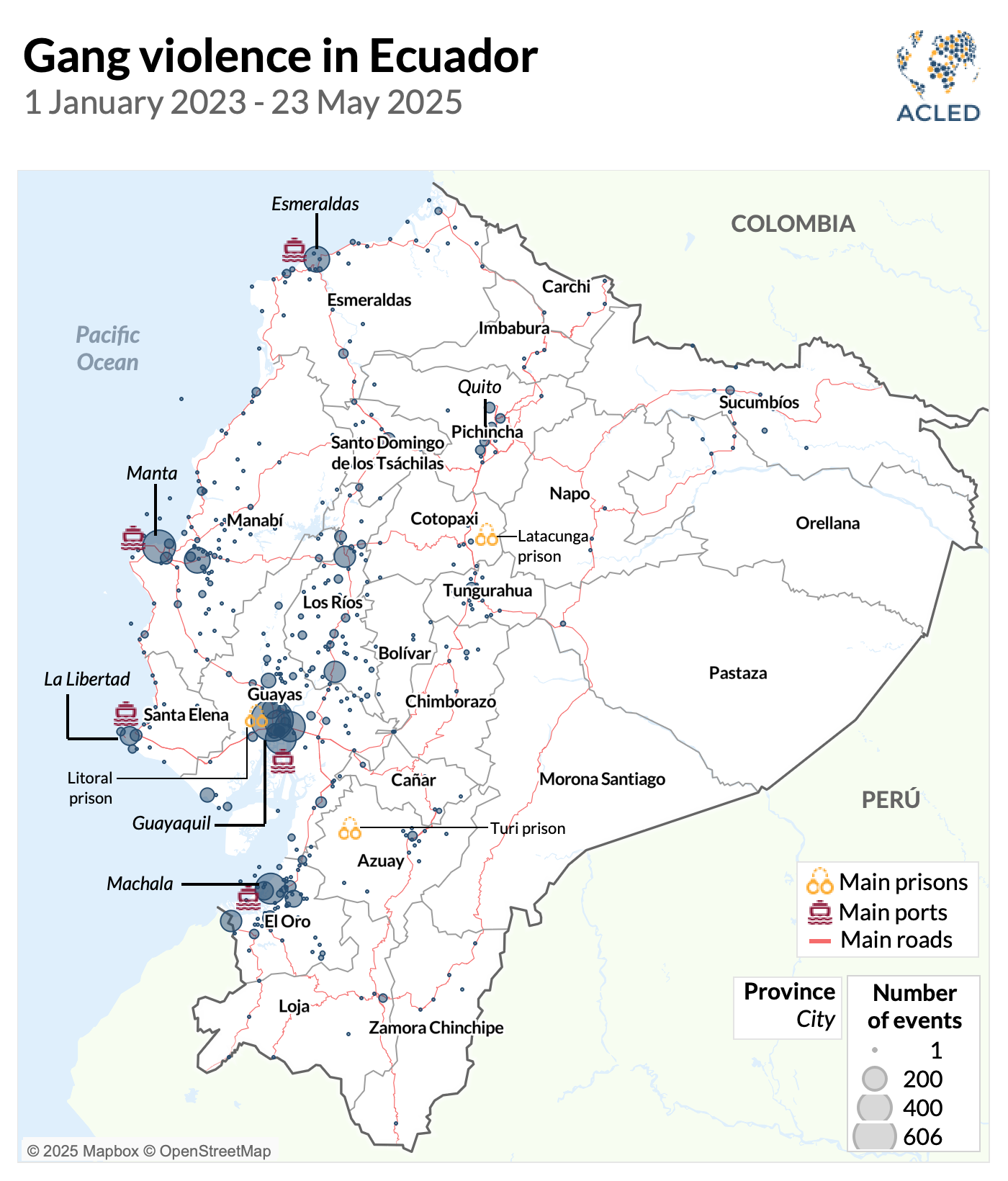

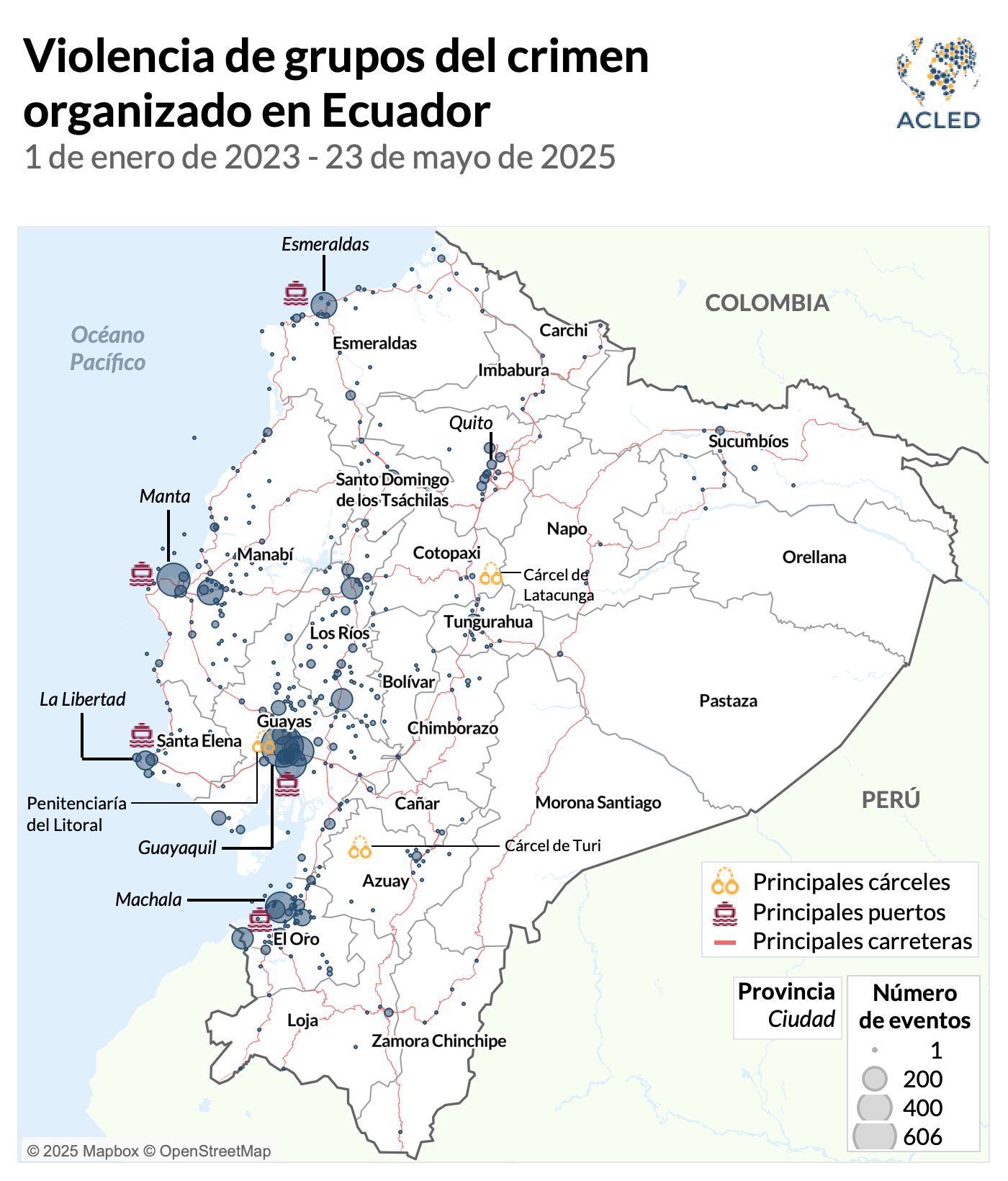

Changes over the past decade in the drug trade and a progressive debilitation of Ecuador’s institutions have created a fertile ground for several local criminal groups to breed. This, in turn, triggered violent competition for control of illicit economies such as drug trafficking, illegal mining, and extortion, first in prisons — which became gangs’ headquarters in recent years — and then in the streets. Although almost 80% of violence is concentrated in coastal provinces, crucial transit points for drug shipments (see map below), gangs have been expanding their presence to over 150 of the country’s 222 municipalities and are extending their reach to Peru, Chile, and Colombia.1Ojo Público, “From hitmen to a criminal superstructure: Ecuador’s Los Lobos expand into Peru, Chile, and Colombia,” 8 December 2024 (Spanish); Gavin Voss, “The Criminal Creep of Ecuador’s Gangs Into Peru,” InSight Crime, 25 February 2025 Their ranks are believed to be composed of no less than 15,000 members, but according to some security experts and unofficial military estimates, up to 60,000 people — not only Ecuadorians, but also Colombian, Venezuelan, and Peruvian nationals — may be linked to gang activity in the country.2Online interview and personal communication with Ecuadorian security experts, ACLED, 1 April and 17 April 2025; El Diario, “Ecuador. Daniel Noboa says that the narco-criminal gangs have between 14,000 and 15,000 armed men,” 19 March 2025 (Spanish)

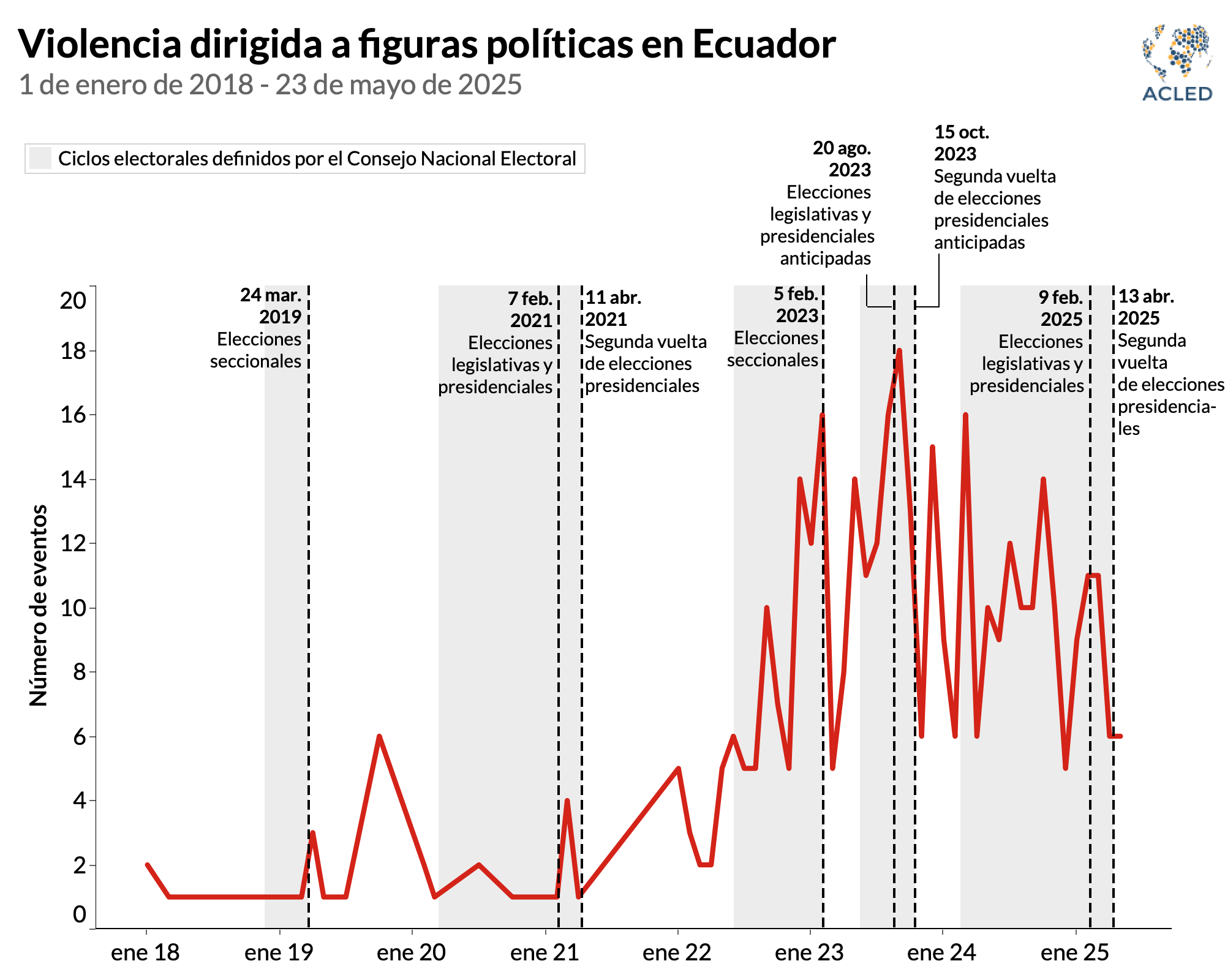

Armed violence has become intertwined with politics. On one hand, security measures and proposals sway public preferences, including in electoral times. On the other hand, criminal and political networks have increasingly resorted to violence to get rid of politicians hindering their interests. The escalation of criminal-political violence reached its apex with the killing of a presidential candidate in 2023. Since then, however, violence targeting political figures seems to have become chronic, owing less to political competition and more to the heightened fights for the control of illicit economies between ever more fragmented criminal groups.

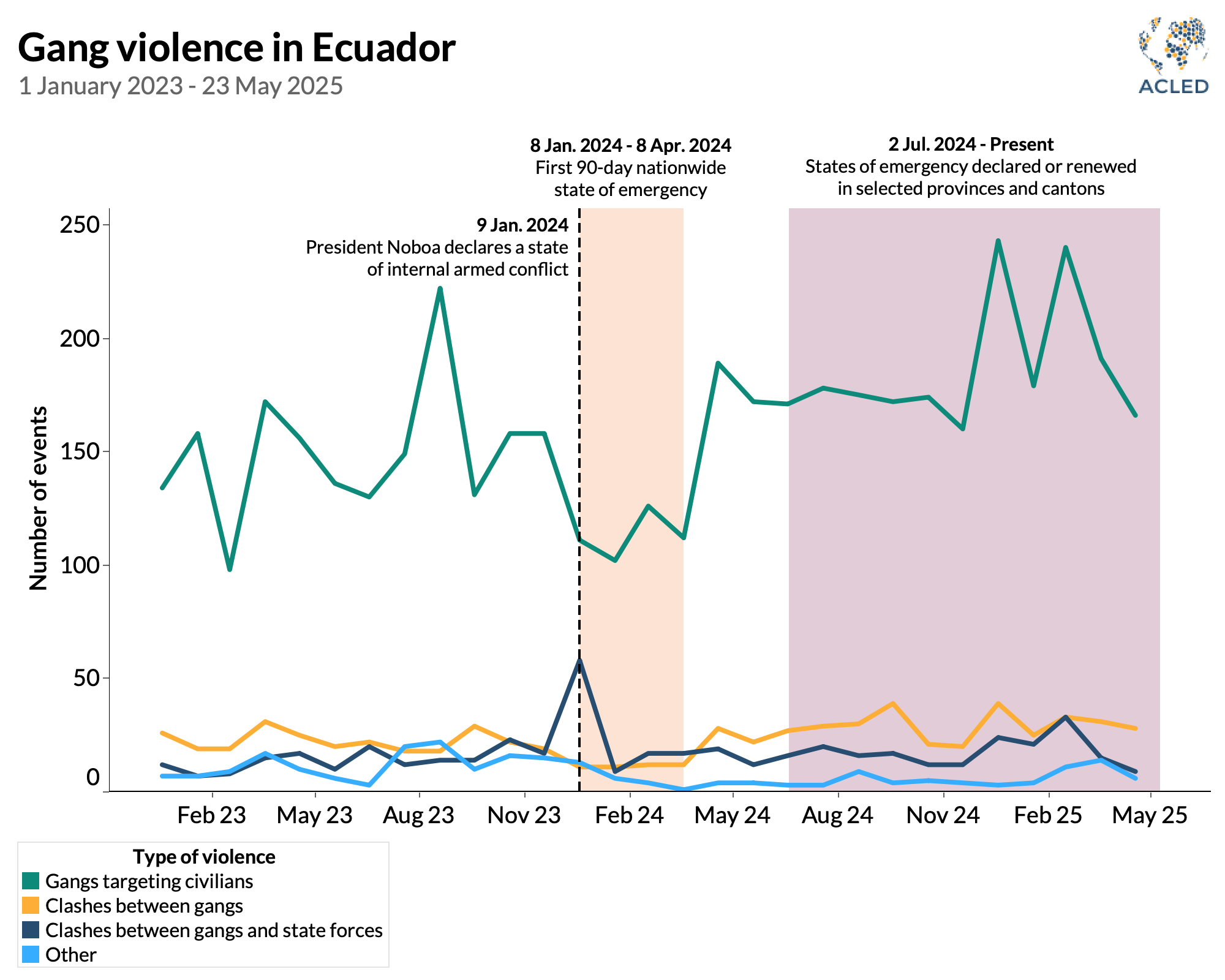

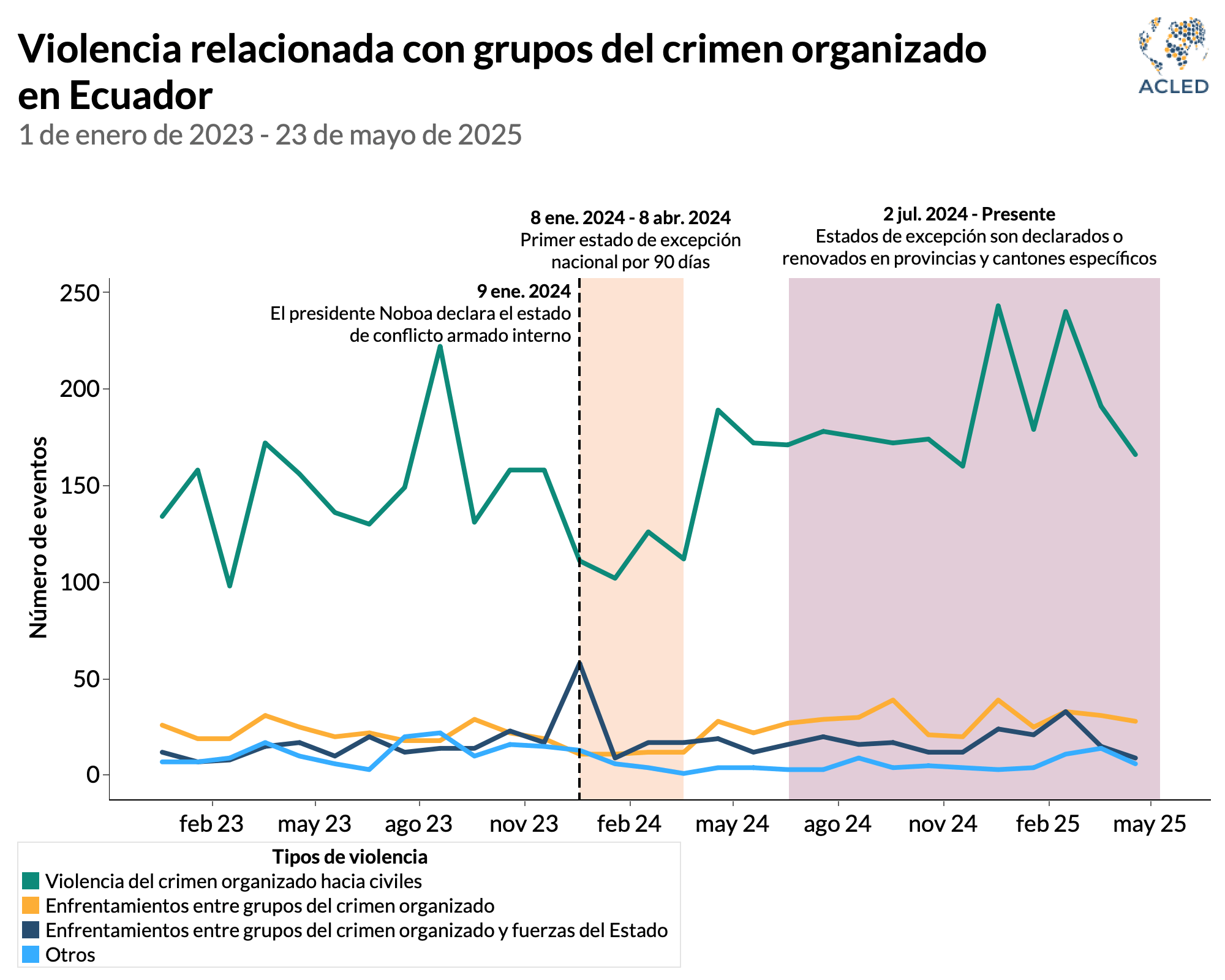

Security policies have also influenced the evolution of violence in the country. Noboa’s declaration of an internal armed conflict in January 2024 and the subsequent militarization of public security initially curbed violence, especially in prisons. However, gangs soon revived their violent competition, and higher government pressure on their leaders helped fuel intra-gang disputes. As a result, the initial lull was reversed, and violence reached unprecedented levels in early 2025. Against this backdrop, the incoming administration faces significant challenges, including gang fragmentation, expanding drug and illegal mining economies, cross-border arms trafficking, and entrenched corruption. How Noboa addresses these challenges will determine Ecuador’s security trajectory in the coming years.

Ecuador’s descent into gang violence

The existence of criminal gangs is not a novelty in Ecuador, but a combination of institutional weakening, economic stagnation, and shifts in international drug trafficking dynamics has profoundly transformed the country’s organized crime landscape.

Soon after he was first elected in 2006, President Rafael Correa negotiated with street gangs originating in the United States and Puerto Rico, such as the Latin Kings and Los Ñetas, essentially recognizing them as civil society organizations in exchange for lower levels of violence. The process contributed to reducing violence to historical lows in the years that followed: In 2017, when Correa left power, Ecuador had a murder rate of six homicides per 100,000 inhabitants, one of the lowest in Latin America.3Online interview with a British academic, ACLED, 24 January 2024; David C. Brotherton and Rafael Gude, “Social Control and the Gang: Lessons from the Legalization of Street Gangs in Ecuador,” Critical Criminology, pp. 931-955, 14 May 2020 But many analysts consulted for this report argue that gangs took advantage of the process to infiltrate state institutions. For example, Leandro Norero, a Ñetas member who participated in the process, became one of the key players in the country’s criminal world, exploiting political connections to expand his illicit activities, as unveiled by recent corruption cases.4Online interviews with Ecuadorian journalists and security experts, ACLED, January and February 2024, April 2025; Steven Dudley and Alina Manrique, “Dealing with the Devil: How Latin Kings in Ecuador Sought Peace, Waged Crime,” InSight Crime, 26 September 2024; Primicias, “Corruption: Three Cases and 76 Defendants Tarnish the State and Political Parties,” 29 March 2024 (Spanish)

Another controversial decision Correa made was to shut down the US military base in charge of monitoring drug trafficking activities in Manta in 2008, claiming it violated the country’s sovereignty.5Simon Romero, “Ecuador’s Leader Purges Military and Moves to Expel American Base,” New York Times, 21 April 2008 His successor, Lenín Moreno (2017-2021), withdrew government support from the pacification process, disbanded the Justice Ministry and the Anti-Corruption Secretariat, and slashed funding for prisons by 30%, as part of a package of austerity measures.6Guillame Long, “How Did Ecuador Spiral into This Nightmare? It Was the Neoliberal Dismantling of the State,” Center for Economic and Policy Research, 31 January 2024 In parallel, the prison population more than tripled between 2010 and 2020, breeding powerful criminal networks within prisons.7See World Prison Brief data here.

As Ecuador’s institutions were weakening because of these steps, the country became an increasingly appealing destination for drug trafficking and money laundering activities, considering its geographic location between the largest cocaine producers, Colombia and Peru; its export-oriented ports; and its dollarized economy.8Tom Phillips, “‘The cocaine superhighway’: how death and destruction mark drug’s path from South America to Europe,” The Guardian, 12 June 2024 International criminal organizations from Mexico, Albania, and Italy stepped up their presence.9Gabriel Stargardter, “How Balkan gangsters became Europe’s top cocaine suppliers,” Reuters, 2 May 2024 At the same time, the peace agreement signed in 2016 between the Colombian government and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) created a void in the regulation of the southbound flow of drugs, primarily cocaine, creating a sort of liberalization of the trade and fostering competition among local groups with volatile alliances with international buyers.10Anna Gordon, “How Gang Violence Is Shaking Up Ecuador’s Election,” Time, 19 August 2023

This combination of domestic and international factors prompted local gangs — headquartered in the country’s prisons and mostly dedicated to murder for hire, car thefts, and security for drug shipments — to strengthen and absorb or replace pre-existing street gangs. As they grew stronger, these criminal groups diversified their economic portfolio into extortion, kidnapping, illegal mining, human smuggling, medication contraband, fuel theft, and wildlife trafficking.11Vanda Felbab-Brown and Diana Paz García, “Ecuador’s elections, organized crime, and security challenges,” Brookings Institute, 3 February 2025

Initially, outfits such as Los Águilas, Los Lobos, Los Tiguerones, and Chone Killers cooperated under the Los Choneros gang umbrella, led by Jorge Luis Zambrano, known as “Rasquiña.” But tensions over leadership arose, also fueled by the growing competition between Mexico’s Sinaloa Cartel and the Jalisco New Generation Cartel (CJNG), which was projected into Ecuador.12International Institute for Strategic Studies, “The Expansion and Diversification of Mexican Cartels: Dynamic New Actors and Markets,” Armed Conflict Survey, 12 December 2024 According to a former prison official consulted by ACLED, Rasquiña established relations with the Sinaloa Cartel and envisioned local gangs to remain its logistical arms.13Online interview with a former Ecuadorian prison official, ACLED, 1 April 2025 Around 2020, however, the CJNG made inroads in the country and sought to ally with some gangs, namely Los Lobos.14Observatorio Ecuatoriano de Crimen Organizado (OECO), “Situational Assessment of the Strategic Environment of Drug Trafficking in Ecuador,” p.88, 18 July 2023 (Spanish) This fueled tensions among gangs over the management of illicit economies, leading to Rasquiña’s killing in December 2020, which was a turning point that triggered a violent competition for leadership.15James Bargent, “Rasquiña’s Revolution: How the Choneros Took Ecuador’s Prisons,” InSight Crime, 28 November 2024 Internecine violence first broke out in prisons, epitomized by the multiple massacres of 2021.16James Bargent, “The prison system in Ecuador – History and challenges of an epicenter of crime,” InSight Crime, 12 December 2024, pp.22-23 It then spread on the streets, triggering multiple conflicts, from which Los Lobos have emerged as the main perpetrator of violence in their quest to become a hegemonic power in the country’s criminal world (see graph below).

The growth of criminal groups and the intensification of their turf wars turned Ecuador into the most violent country in Latin America in 2023, with a murder rate of 44.5 homicides per 100,000 inhabitants, a record it has maintained ever since.17Juliana Manjarrés and Christopher Newton, “InSight Crime’s 2023 Homicide Round-Up,” InSight Crime, 21 February 2024 In 2024, ACLED records more violent events in Ecuador than in neighboring Colombia, a country roughly four times bigger with nearly triple the population (see table below). Gang-related violence has predominantly affected the coastal provinces, key off-ramps for drug shipments bound to North America and Europe. Almost 80% of recorded gang violence has taken place in five of the country’s 24 provinces: Guayas, Manabí, El Oro, Santa Elena, and Esmeraldas. The city of Guayaquil, which hosts the country’s biggest port and is crucial for drug shipments, is the hotbed of violence, accounting for around one-fourth of gang violence events recorded so far in Ecuador and ranking just behind Rio de Janeiro and Salvador in Brazil for total number of gang-related events in both 2023 and 2024 across Latin America (see table below).

| Non-state armed groups’ violence in Latin America in 2024 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| By country | By city | ||

| Country | Number of events | City | Number of events |

| 1. Brazil | 8,945 | 1. Rio de Janeiro, Brazil | 1,243 |

| 2. Mexico | 7,191 | 2. Salvador, Brazil | 915 |

| 3. Ecuador | 2,389 | 3. Guayaquil, Ecuador | 570 |

| 4. Colombia | 2,157 | 4. Culiacán, Mexico | 489 |

| 5. Venezuela | 465 | 5. León, Mexico | 420 |

Yet, the diversification of gangs’ economic portfolio has driven their expansion inland, particularly around mining sites and along the country’s major highways, which gangs use to extort export-oriented businesses in the agriculture, textile, and industrial sectors.18Online interviews with an Ecuador-based security expert and Renato Rivera, director of the Ecuadorian Organized Crime Observatory, ACLED, April and May 2025 In fact, ACLED records gang presence in around two-thirds of the country’s 222 municipalities since 2023. Los Ríos, which connects coastal provinces with the center of the country, is the fourth most violent province. Los Ríos is also among the provinces where gang violence increased the most in 2024, together with provinces in the Andes and Amazon such as Azuay, Tungurahua, and Sucumbíos.

The intersection of gangs, politics, and elections

Organized crime violence has become intrinsically intertwined with politics and elections in Ecuador. Security is a central theme in political processes, since results in that realm heavily affect governments’ public approval, and security plans are key pillars of electoral campaigns. Violence has also increasingly become a feature of political competition, as organized crime groups take on political figures who hinder their interests, following similar trends in other Latin American countries such as Mexico, Brazil, and Colombia.

The deterioration of Ecuador’s security situation since 2020 has tainted the image of former President Guillermo Lasso, a conservative who, by the end of 2022, had only a 13% public approval rating.19Voz de América, “Ecuador: Insecurity Undermines the Government’s Credibility,” 29 December 2022 (Spanish) As a result, opposition forces defeated conservative parties in the February 2023 local elections, and some government-proposed security reforms were rejected in a referendum.20Alexandra Valencia, “Ecuador’s Lasso accepts extradition referendum defeat; opposition wins mayoral races,” Reuters, 7 February 2023 A journalistic investigation also found evidence of Lasso’s involvement in embezzlement schemes, as well as links between his brother-in-law and the Albanian mafia. The investigation prompted the National Assembly to start impeachment proceedings against Lasso.21La Posta, “The Great Godfather,” 9 January 2023 (Spanish) To avoid impeachment, Lasso dissolved the National Assembly in May 2023 and called for early elections.22Andrés Granadillo, “Ecuador: Impeachment Request Against Lasso Advances Over Alleged Corruption Offenses,” France 24, 21 March 2023 (Spanish); Tom Phillips and Dan Collyns, “Ecuador’s embattled president dissolves congress in bid to avoid impeachment,” The Guardian, 17 May 2023 Noboa, a young entrepreneur who promised a tough-on-crime approach, won the runoff election against left-wing candidate Luisa González in October 2023 and was appointed to serve until the end of Lasso’s term in May 2025.23Dan Collyns, “Banana fortune heir Daniel Noboa wins Ecuador presidential election,” The Guardian, 16 October 2023

Insecurity remained at the center of the public debate in the run-up to the 2025 elections: Some 60% of interviewees in a late 2024 poll identified violent crime as the country’s main problem,24IPSOS, “A look at 2024: Who do Ecuadorians trust, and what were their main concerns in 2024?” 31 December 2024 (Spanish) and most presidential candidates proposed military interventions and tougher policies to combat criminal organizations.25Steven Dudley, “How Organized Crime Set the Agenda for Ecuador’s Presidential Elections,” InSight Crime, 5 February 2025 Noboa, running for re-election, even proposed bringing in foreign forces, including mercenaries, for that purpose.26Abel Alvarado, David Culver, and Barbara Arvanitidis, “Ecuador is preparing for US forces, plans show, as Noboa calls for help battling gangs,” CNN, 29 March 2025

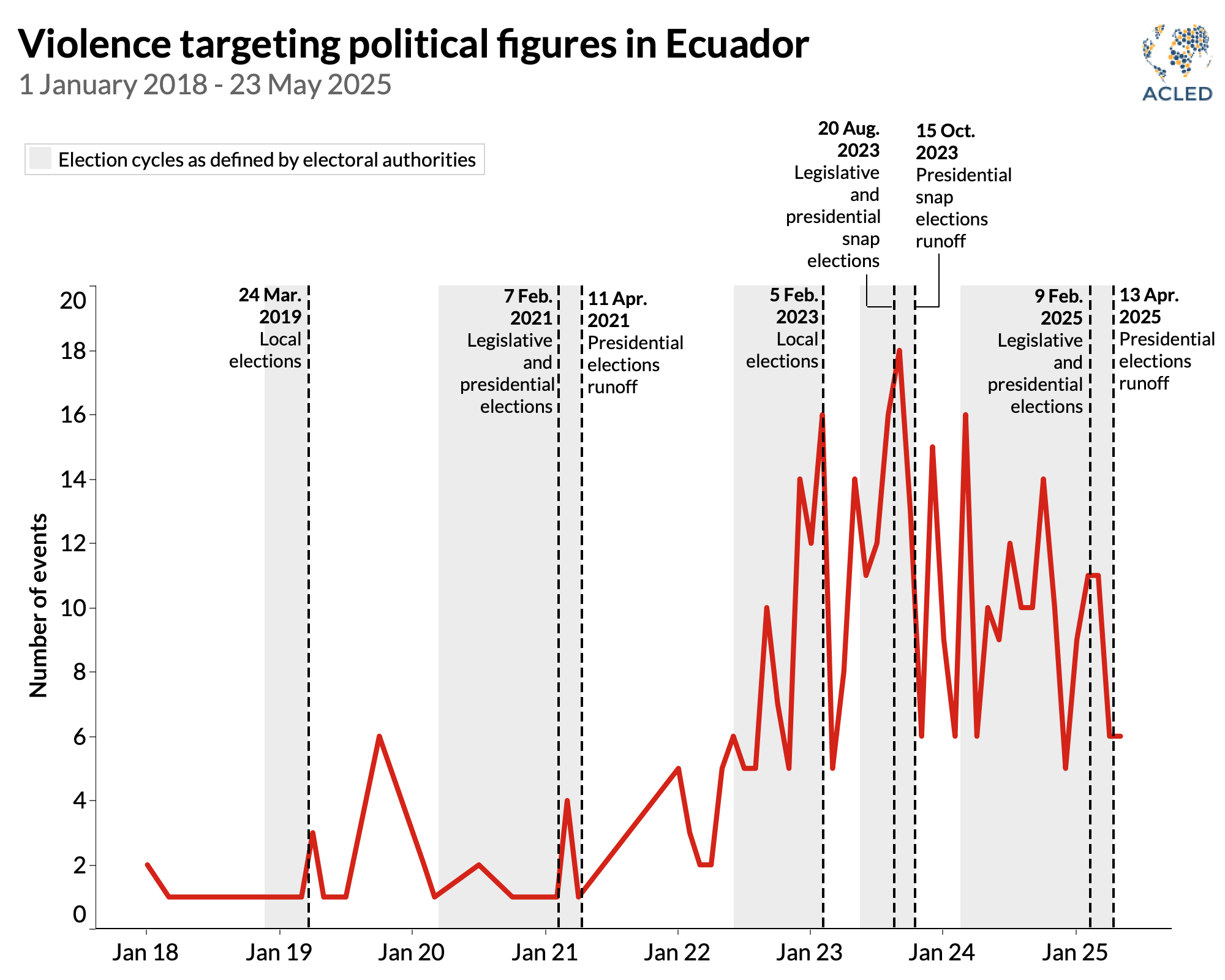

Since the 2023 electoral cycle, violence has not only swayed political developments but has also penetrated political competition. Between when ACLED began covering Ecuador in 2018 and 2021, there were 30 events of violence against elected officials, government workers, candidates, and their relatives, which led to the death of five people. Things changed in 2022: In the year leading up to the local elections on 5 February 2023, the number of events went up to 89 (see graph below). This violence further accelerated during the August snap elections: ACLED records similar levels of violence in the five months between Lasso’s call for early elections and the presidential runoff. During the two electoral processes, 99 people were killed in incidents of violence against political figures, including presidential candidate Fernando Villavicencio. Prosecutors believe that Los Lobos gang members carried out his murder, but the plotters of the attack have yet to be identified.27Vanessa Buschschlüter, “Villavicencio murder ‘planned from jail’ by Los Lobos gang – prosecutors,” BBC, 28 February 2024

While much of the violence targeting political figures had a clear link with the electoral process in 2022 and 2023, it has since become endemic. In fact, monthly violence against political figures remained high during the 2025 electoral process (see graph above), which can be said to be the most violent since ACLED began covering the country in 2018, with over 140 events. However, there were fewer events targeting candidates than in the 2023 electoral processes. This can be partly explained by the fact that the government stepped up protection measures of candidates, particularly presidential hopefuls,28Primicias, “Nine Police Officers per Candidate: How the Police Will Shield Presidential Candidates in Ecuador,” 20 November 2024 (Spanish) and reduced campaign activities.29Carolina Mella, “Candidates Limit Their Campaign Events in Ecuador Due to Fear of Violence,” El País, 16 January 2025 (Spanish) But another factor may have been the level of the elections: Candidates tend to be particularly targeted in local elections, as gangs more actively seek to impede the election of officials who hinder their territorial control.30Online interview with Renato Rivera, director of the Ecuadorian Organized Crime Observatory, ACLED, 13 May 2025 Yet, other political figures continued to face high levels of violence: Transit agents, prison directors, and judicial officials were the targets in nearly one-third of events, and organized crime groups typically attacked them to ensure impunity for their illicit activities and hinder their adversaries.31Online interview with an Ecuador-based security expert, ACLED, 11 April 2025 This suggests that violence against political figures has come to mirror the country’s security deterioration and is being driven more by gang expansion, territorial competition, and fragmentation rather than political competition.

The impact of the internal armed conflict on gangs’ adaptation and fragmentation

Noboa’s re-election is a testament to the majority of Ecuadorians’ approval of his security policy, whose most prominent measures have been the declaration of an internal armed conflict, the repeated imposition of states of emergency, and the military’s expanded role in public security. In 2024, the country’s homicide rate slightly decreased for the first time since 2019, even though it remained the highest in Latin America.32Marina Cavalari, Juliana Manjarrés, and Christopher Newton, “InSight Crime’s 2024 Homicide Round-Up,” InSight Crime, 26 February 2025 However, the same measures that contributed to reining in violence in the first months of 2024 — increased military pressure in prisons and on the streets — had the unintended consequence of further fostering intra-gang power struggles and fragmentation. This ultimately led to a resurgence of violence at the end of the year and the most violent four months the country has ever recorded at the beginning of 2025.33Primicias, “Ecuador recorded a 58% increase in homicides during the first four months of 2025,” 21 May 2025 (Spanish)

In January 2024, Noboa’s security policy took a militarized turn. After the Los Choneros leader escaped from prison, Noboa announced a nationwide state of emergency, to which gangs responded with a series of coordinated attacks. Los Tiguerones gang members even stormed a TV studio in Guayaquil.34Marita Moloney and Patrick Jackson, “Ecuador declares war on armed gangs after TV station attacked on air,” BBC, 10 January 2024 In response, Noboa declared a state of internal armed conflict on 9 January, designating 22 violent criminal gangs as “terrorist organizations” and tasking the armed forces with participating in security operations in gang-controlled neighborhoods and illegal mining hotspots and taking over control in prisons.35The gangs designated as terrorist groups are: Águilas, ÁguilasKiller, Ak47, Caballeros Oscuros, ChoneKiller, Choneros, Covicheros, Cuartel de las Feas, Cubanos, Fatales, Gánster, Kater Piler, Lagartos, Latin Kings, Lobos, Los p.27, Los Tiburones, Mafia 18, Mafia Trébol, Patrones, R7, and Los Tiguerones. TeleSur English, “Noboa declares internal armed conflict in Ecuador,” 9 January 2024 Even though the Constitutional Court later ruled that the situation in the country did not meet the criteria to be considered an internal armed conflict, the government has continued to use the term to justify imposing a series of nationwide or province-specific states of emergency.36Primicias, “The Constitutional Court calls out Noboa for insisting on the existence of an internal armed conflict,” 2 August 2024 (Spanish) This move increased government pressure and was met with harsh resistance by gangs, which, in the words of a security expert consulted for this report, “took the concept of internal armed conflict more seriously than the government itself, increasing their attacks.”37Online interview with an Ecuadorian security expert, ACLED, 9 April 2025 As a result, ACLED records 58 events of violence between gangs and security forces in January 2024, with 9 January being the day with the most violence since 2023.

Despite the immediate backlash, the massive deployment of military forces in both prisons and on the streets had a temporary impact on gang activities, particularly on clashes between gangs and the targeting of civilians amid gang wars (see graph below). ACLED records 128 events of gang violence in February, 34% fewer than in January and the lowest since January 2023. These remained at relatively low levels for the rest of the first three-month state of emergency. Violence dropped inside prisons, home to several bouts of deadly violence in previous years. In the first year since military forces took control of the prison system on 14 January, clashes between gangs and targeted attacks on prisoners by gang members decreased by 64% compared to the year prior. Moreover, reported fatalities resulting from gang violence went down by two-thirds, particularly in the Guayaquil Penitentiary.

Security forces’ scaled-up operations translated into more clashes with gangs, many times rescuing people from kidnapping attempts. But these operations were not exempt from criticism as the military has also been accused of gross human rights violations, including excessive use of force, forced disappearances, sexual violence, and torture.38Online interview with Billy Navarrete, director of the Permanent Committee for the Defense of Human Rights, ACLED, 2 May 2025 In 2024, authorities claimed to have detained over 73,000 people, but the vast majority were released, mostly due to a lack of evidence.39Primicias, “Only four out of every ten detainees remained in prison in 2024, despite the militarization process in Ecuador,” 2 March 2025 (Spanish) Meanwhile, the Guayaquil-based Permanent Committee for the Defense of Human Rights records at least 33 victims of forced disappearance at the hands of state forces between 2024 and 2025.40Comité Permanente por la Defensa de los Derechos Humanos, “Militarization should not mean cover-up,” 24 April 2025 (Spanish) In perhaps the most disturbing case, four teenagers were abducted and tortured by the military in Guayaquil on 8 December 2024. The remains of their bodies were found incinerated a couple of weeks later.41Tiago Rogero, “Ecuador confirms incinerated bodies belong to missing ‘Guayaquil Four’ boys,” The Guardian, 31 December 2024 A human rights defender consulted for this report expressed concern that these events occurred amid Noboa’s repeated offers to pardon those who commit abuses.42Online interviews with an Ecuador-based human rights defender, ACLED, 4 April 2025; Yalilé Loaiza, “Daniel Noboa promised to pardon police officers and military personnel after the massacre in Guayaquil: “Defend Ecuador, and I will defend you”,” Infobae, 7 March 2025 (Spanish)

But the short-term reduction in violence was soon reversed as gangs adapted to the new reality and grew increasingly fragmented. Unlike Haiti, where gangs overcame longstanding rivalries and formed a relatively stable alliance to fight against state forces in September 2023, Ecuador’s wave of coordinated gang attacks against security forces was short-lived and did not morph into greater cooperation. On the contrary, interventions in prisons and gang-controlled communities hindered communications between imprisoned and free gang leaders and prompted some leaders to go into hiding or even leave the country, sparking internal power struggles and leading to the creation of further offshoot gangs.43Online interview with an Ecuador-based security expert, ACLED, 11 April 2025 ACLED records activity of at least 37 gangs in 2024, 54% more than in 2023, as part of what a security expert calls a “second wave of fragmentation,” after the one that led to the disintegration of the Choneros-led confederation.44Online interview with Renato Rivera, director of the Ecuadorian Organized Crime Observatory, ACLED, 13 May 2025 For example, Chone Killers leaders known as Trompudo and Ben 10 were killed in Cali, Colombia, in December 2024, and violent competition between local leaders running neighborhoods in Durán, Guayas, ensued.45Primicias, “After the crimes of ‘Ben 10’ and ‘Trompudo Israel’, three leaders of the Chone Killers emerge as their successors,” 30 December 2024 (Spanish)

In parallel, competition also resumed in prisons, as the military control of prisons started to crack in the second half of the year and gangs tried to regain control of the prison economies.46Online interviews with an Ecuador-based security expert and Billy Navarrete, 11 April and 2 May 2025 On 12 November, a dispute between Los Duendes and Los Freddy Kruegers gangs over the control of food distribution led to the killing of at least 17 prisoners in the Litoral Penitentiary.47Steven Dudley and James Bargent, “Jailhouse massacre in Ecuador illustrates rapid criminal evolution,” InSight Crime, 28 November 2024

Above all, civilians have paid a high toll for the resurgence of gang activities and disputes (see graph above). In many cases, gangs target civilians who refuse to pay extortion fees. In other cases, these events are related to territorial disputes. According to a security expert consulted by ACLED, one group often attacks civilians “to show that the opposing group does not have the capacity to protect its people, in order to replace it and start asking for higher extortion payments.”48Online interview with an Ecuador government official, ACLED, 29 August 2024 Taxi drivers and other labor groups, such as merchants, mechanics, and fishermen, are some of the most targeted for extortion. But civilians more directly associated with gangs, such as collaborators or members’ relatives, can also be direct victims of gang disputes. For example, on 7 March 2025, 22 people were massacred and at least 120 families were forcibly displaced in the Socio Vivienda neighborhood in Guayaquil, as part of the war between Los Fénix and Los Igualitos factions of Los Tiguerones gang, which was triggered by the capture of its leaders in Spain in October 2024.49Online interview with Renato Rivera, director of the Ecuadorian Organized Crime Observatory, ACLED, 13 May 2025; Al Jazeera, “At least 22 people killed as gang violence erupts in Ecuador,” 7 March 2025; Deborah Bonello and James Bargent, “Arrest of Leaders of Ecuador’s Tiguerones Could Further Fracture Gang,” InSight Crime, 23 October 2024 Successive states of emergency imposed on the most violent provinces and cantons have failed to curb violence. On the contrary, violence picked up steam, both in and outside prisons, reaching record-high levels in early 2025.50Alexander García, “The first quarter of 2025: the most violent in Ecuador’s recent history,” Primicias, 21 April 2025 (Spanish) Between 1 January and 23 May 2025, ACLED records over 1,300 events of gang violence, over 60% more than in the same period in 2024.

What comes next will depend on Noboa’s plans, but only in part

Noboa starts his new term amid an escalation of gang violence. Despite his victory, doubts abound over whether he will be able to drag Ecuador out of this crisis. Part of this titanic task will depend on his policy and political decisions; the other part will depend on factors outside his control.

Internally, Noboa’s militarization since early 2024 has resulted in the fragmentation of criminal gangs and rapid turnover in their leadership. To avoid a Mexico-like scenario, where organized crime groups’ splintering and shifting alliances have fueled a constant escalation of violence over the last few decades, he will need a comprehensive plan that goes beyond ad-hoc and temporary deployment of armed forces in both prisons and on the streets.51Online interviews with Ecuadorian security experts, ACLED, April and May 2025; Steven Dudley, “Elected for a full term, Ecuador’s Noboa needs a plan,” InSight Crime, 14 April 2025 At the same time, Noboa faces a deeply polarized landscape with a tenuous majority in the National Assembly, which complicates governance and the passing of critical reforms,52Sebastian Jimenez, “Daniel Noboa consolidates power in Ecuador as regional right wing gains momentum,” CNN, 14 April 2025 as well as a stagnating economy, which will limit his wiggle room to offer alternatives to the country’s disenfranchised youth.53The Economist, “Ecuador chooses a leader amid murder, blackouts and stagnation,” 6 February 2025 Meanwhile, criminal interests remain deeply embedded in the political, judicial, and security sectors, despite some efforts to expose and combat them. Further progress to root them out will depend on the commitment of the upcoming attorney general, due to be appointed, and the government’s willingness to collaborate with them.54Gavin Voss, “Corruption Sentences Pile Up in Ecuador, But Will It Matter?” InSight Crime, 21 March 2025

But the government will also have to face the fact that some of the main drivers of the country’s illicit economies that gangs fiercely fight to control, such as cocaine and illegal gold mining, are booming. Cocaine production reached record levels in 2023,55Oscar Medina, “Colombia’s Potential Cocaine Production Surges to a Record High,” Bloomberg, 19 October 2024 and Colombian rebel groups’ disputes for the control of the southern coca-producing departments of Nariño and Putumayo, bordering Ecuador, are far from over. Shifting alliances and territorial control between Colombian and Ecuadorian armed groups raise the risk of increasing violence on both sides of the border. At the same time, the global surge in gold prices has triggered a boom in illegal mining, drawing Ecuadorian but also Colombian criminal organizations deeper into the country’s Amazonian and Andean regions, further contributing to increasing violence against security forces56France 24, “Ecuador declares national mourning for 11 troops killed by guerrillas,” 10 May 2025 and political figures.57Arturo Torres and Dan Collyns, “In Ecuador, booming profits in small-scale gold mining reveal a tainted industry,” Mongabay, 3 October 2024; Gavin Voss, “Ecuador’s Lobos Turn El Oro Province Into Battleground,” InSight Crime, 27 January 2025 Finally, Ecuador’s porous 1,500-kilometer border with Peru has facilitated arms trafficking from the neighboring country, which is also experiencing a deteriorating security situation.58Ojo Público, “From the Peruvian Army to Ecuador’s mafias: The routes of arms trafficking on the border,” 14 January 2024 (Spanish); Carla Álvarez, “PARADISE LOST? FIREARMS TRAFFICKING AND VIOLENCE IN ECUADOR,” Global Initiative against Transnational Organized Crime, June 2024, p.22 (Spanish)

Addressing this convergence of security, economic, and political challenges will require not only a coherent national strategy but also strong cooperation with neighboring countries and international allies. His proposals — which rely on perpetual states of emergency, building new maximum security prisons, and increasing sanctions for gang-related crimes — seem to draw much on El Salvador’s President Nayib Bukele’s playbook. But even if these measures dealt a huge blow to gangs in El Salvador, the suspension of due process and thousands of arbitrary arrests came at a huge cost to the country’s democratic standards.59Oliver Stuenkel, “Ecuador’s Challenge: Rout Organized Crime Without Endangering Democracy,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 18 April 2025 Unlike his first time in office, Noboa now has a full term to craft a security approach that can certainly draw on successful examples from the region but needs to adapt to the country’s criminal and institutional specificities. The four-year time frame gives him the chance to achieve more substantial results, but it will also make failure more visible.

Correction: On 8 October 2024, Ecuador created a new municipality. This report has been updated to reflect that the total municipalities in the country is 222, instead of 221.

Visuals in this report were produced by Ciro Murillo

Contribution of The University of Texas at Austin (UT)

The data used for this report was enriched by the work of students at the University of Texas at Austin (UT). These include Ty Burroughs, Geraldyn Campos, Tamon Hamlett, Zee Khan, and Noemi Mora, under the direction of Dr. Ashley Moran in the UT Government Department. UT identified and tagged events of election-related disorder and violent events targeting national administrators in Ecuador between January 2018 and August 2024. The project contributes to the tracking of violence targeting administrators and understanding their manifestations in national and subnational political settings. The election-related disorder tags allow the tracking of unrest that arises during electoral processes, such as violence targeting electoral infrastructure and officials, demonstrations linked to elections (e.g., electoral reforms, contestation of results, etc.), and violence against relatives of politicians, which is a tool frequently used by power brokers to put pressure on political figures.

Noboa declaró la guerra a 22 grupos criminales en Ecuador. En su nuevo mandato, se enfrenta a muchos más.

Cómo la violencia implacable de los grupos criminales ha puesto a prueba la estrategia de militarización del presidente

El 24 de mayo, Daniel Noboa, presidente derechista en funciones, tomó posesión en Ecuador, tras ganar la segunda vuelta de las elecciones presidenciales contra la izquierdista Luisa González. Las elecciones tuvieron lugar en medio de una ola de violencia sin precedentes vinculada al crimen organizado en un país que un tiempo fue uno de los lugares menos violentos de América Latina, pero que rápidamente se convirtió en el país más violento de la región, un título trístemente famoso que ha mantenido desde 2023.

Los cambios en la última década en el comercio de la droga y el debilitamiento progresivo de las instituciones ecuatorianas han creado un terreno fértil para la proliferación de grupos criminales locales. Esto, a su vez, desencadenó una competencia por el control de las economías ilícitas como el narcotráfico, la minería ilegal, y la extorsión, primero en las prisiones —que se convirtieron en cuarteles generales de los grupos criminales en los últimos años— y luego en las calles. Aunque casi el 80 % de la violencia se concentra en las provincias costeras, puntos de tránsito cruciales para los envíos de droga (véase el mapa a continuación), los grupos criminales han ido expandiendo su presencia a más de 150 de los 222 cantones del país y están ampliando su alcance a Perú, Chile y Colombia.1Ojo Público, “De sicarios a superestructura criminal: Los Lobos de Ecuador avanzan en Perú, Chile y Colombia,” 8 de diciembre de 2024; Gavin Voss, “The Criminal Creep of Ecuador’s Gangs Into Peru,” InSight Crime, 25 de febrero de 2025 Se cree que sus filas están compuestas por no menos de 15 000 miembros, pero según algunos expertos en seguridad y estimaciones militares no oficiales, hasta 60 000 personas —no solo ecuatorianos, sino también colombianos, venezolanos y peruanos— podrían estar vinculadas a la actividad del crimen organizado en el país.2Entrevista en línea y comunicación personal con expertos en seguridad ecuatorianos, ACLED, 1 de abril y 17 de abril de 2025; El Diario, “Ecuador. Daniel Noboa dice que las bandas narco criminales tienen entre 14 mil y 15 mil hombres armados,” 19 de marzo de 2025

La violencia armada se ha entrelazado con la política. Por un lado, las medidas y propuestas de seguridad influyen las preferencias ciudadanas, especialmente en épocas electorales. Por otro lado, las redes criminales y políticas han recurrido cada vez más a la violencia para deshacerse de los políticos que obstaculizan sus intereses. La escalada de la violencia político criminal alcanzó su punto más álgido con el asesinato de un candidato presidencial en 2023. Desde entonces, la violencia contra figuras políticas parece haberse vuelto crónica, debido menos a la competencia política y más a la intensificación de las luchas por el control de las economías ilícitas entre grupos criminales cada vez más fragmentados.

Las políticas de seguridad también han influenciado la evolución de la violencia en el país. La proclamación de Noboa de un conflicto armado interno en enero de 2024 y la subsiguiente militarización de la seguridad pública frenó inicialmente la violencia, en particular en las prisiones. Sin embargo, los grupos criminales pronto reanudaron su violenta competencia, y la mayor presión del gobierno sobre sus líderes contribuyó a alimentar las disputas dentro de los mismos grupos criminales. Como resultado, la calma inicial se revirtió, y la violencia alcanzó niveles sin precedentes a principios de 2025. En este contexto, la administración entrante se enfrenta a desafíos considerables, incluidas la fragmentación de los grupos criminales, la expansión de las economías de la droga y la minería ilegal, el tráfico transfronterizo de armas y la corrupción arraigada. La forma en la que Noboa aborde estos desafíos determinará la trayectoria de Ecuador en materia de seguridad en los próximos años.

El descenso de Ecuador hacia la violencia del crimen organizado

La existencia de grupos criminales no es una novedad en Ecuador, pero una combinación de debilitamiento institucional, estancamiento económico y cambios en las dinámicas internacionales del narcotráfico ha transformado profundamente el panorama del crimen organizado en el país.

Poco después de ser elegido por primera vez en 2006, el presidente Rafael Correa negoció con los grupos callejeros originados en Estados Unidos y Puerto Rico, como los Latin Kings y Los Ñetas, para esencialmente reconocerlos como organizaciones de la sociedad civil a cambio de bajar los niveles de violencia. El proceso contribuyó a que se redujera la violencia a mínimos históricos en los años sucesivos: en 2017, cuando Correa dejó el poder, Ecuador tenía una tasa de seis homicidios por cada 100 000 habitantes, una de las más bajas de América Latina.3Entrevista en línea con un académico británico, ACLED, 24 de enero de 2024; David C. Brotherton y Rafael Gude, “Social Control and the Gang: Lessons from the Legalization of Street Gangs in Ecuador,” Critical Criminology, pp. 931-955, 14 de mayo de 2020 Sin embargo, muchos analistas consultados para este informe sostienen que los grupos criminales se aprovecharon del proceso para infiltrarse en las instituciones del Estado. Por ejemplo, Leandro Norero, un miembro de los Ñetas que participó en el proceso, se convirtió en uno de los actores principales en el mundo del crimen en el país, explotando sus conexiones políticas para expandir sus actividades ilícitas, como han revelado algunos recientes casos de corrupción.4Entrevistas en línea con periodistas y expertos en seguridad ecuatorianos, ACLED, enero y febrero de 2024, abril de 2025; Steven Dudley y Alina Manrique, “Dealing with the Devil: How Latin Kings in Ecuador Sought Peace, Waged Crime,” InSight Crime, 26 de septiembre de 2024; Primicias, “Corrupción: tres casos y 76 procesados empañan al Estado y a los partidos políticos,” 29 de marzo de 2024

Otra decisión controvertida de Correa fue la de cerrar en 2008 la base militar estadounidense encargada de monitorear las actividades del narcotráfico en Manta, alegando que violaba la soberanía del país.5Simon Romero, “Ecuador’s Leader Purges Military and Moves to Expel American Base,” New York Times, 21 de abril de 2008 Su sucesor, Lenín Moreno (2017-2021), retiró el apoyo del gobierno al proceso de pacificación, disolvió el Ministerio de Justicia y la Secretaría Anticorrupción, y recortó la financiación de las prisiones en un 30 %, como parte de un paquete de medidas de austeridad.6Guillame Long, “How Did Ecuador Spiral into This Nightmare? It Was the Neoliberal Dismantling of the State,” Center for Economic and Policy Research, 31 de enero de 2024 Asimismo, la población reclusa se triplicó con creces entre 2010 y 2020, engendrando a poderosas redes criminales dentro de las prisiones.7Véanse aquí los datos de World Prison Brief

A medida que las instituciones de Ecuador se iban debilitando debido a estas medidas, el país se convertía en un destino cada vez más atractivo para el narcotráfico y las actividades de lavado de dinero, teniendo en cuenta su situación geográfica entre los mayores productores de cocaína, Colombia y Perú; sus puertos orientados a la exportación; y su economía dolarizada.8Tom Phillips, “‘The cocaine superhighway’: how death and destruction mark drug’s path from South America to Europe,” The Guardian, 12 de junio de 2024 Las organizaciones criminales internacionales de México, Albania e Italia intensificaron su presencia.9Gabriel Stargardter, “How Balkan gangsters became Europe’s top cocaine suppliers,” Reuters, 2 de mayo de 2024 Al mismo tiempo, el acuerdo de paz firmado en 2016 entre el Gobierno colombiano y las Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia (FARC) creó un vacío en la regulación del flujo de drogas hacia el sur, principalmente cocaína, creando una especie de liberalización del comercio y fomentando la competencia entre grupos locales con alianzas volátiles con compradores internacionales.10Anna Gordon, “How Gang Violence Is Shaking Up Ecuador’s Election,” Time, 19 de agosto de 2023

Esta combinación de factores nacionales e internacionales impulsó a los grupos criminales locales —radicados en las prisiones del país y dedicados en su mayoría al sicariato, al robo de carros y a la seguridad de los cargamentos de droga— a reforzarse y absorber o sustituir a los grupos criminales callejeros preexistentes. A medida que se fortalecieron, estos grupos criminales diversificaron su cartera económica hacia la extorsión, el secuestro, la minería ilegal, el tráfico de personas, el contrabando de medicamentos, el robo de combustible y el tráfico de fauna silvestre.11Vanda Felbab-Brown y Diana Paz García, “Ecuador’s elections, organized crime, and security challenges,” Brookings Institute, 3 de febrero de 2025

Al principio, grupos como Los Águilas, Los Lobos, Los Tiguerones y Chone Killers cooperaron bajo el paraguas de la organización Los Choneros, liderada por Jorge Luis Zambrano, conocido como ‘‘Rasquiña’’. Pero surgieron tensiones por el liderazgo, impulsadas también por la creciente competencia entre el Cártel de Sinaloa y el Cártel de Jalisco Nueva Generación de México, la cual se ha proyectado hacia Ecuador.12International Institute for Strategic Studies, “The Expansion and Diversification of Mexican Cartels: Dynamic New Actors and Markets,” Armed Conflict Survey, 12 de diciembre de 2024 Según una exfuncionaria de prisiones consultada por ACLED, Rasquiña estableció relaciones con el Cártel de Sinaloa y apuntó a que los grupos criminales locales siguieran siendo sus brazos logísticos.13Entrevista en línea con una exoficial de prisiones ecuatoriana, ACLED, 1 de abril de 2025 Entorno a 2020, sin embargo, el CJNG se adentró en el país y buscó aliarse con algunos grupos criminales, en concreto Los Lobos.14Observatorio Ecuatoriano de Crimen Organizado (OECO), “Evaluación situacional del entorno estratégico del narcotráfico en Ecuador,” p.88, 18 de julio de 2023 Esto alimentó las tensiones entre los grupos criminales por la gestión de las economías ilícitas, lo que condujo al asesinato de Rasquiña en diciembre de 2020, un punto de inflexión que desencadenó una violenta competición por el liderazgo.15James Bargent, “Rasquiña’s Revolution: How the Choneros Took Ecuador’s Prisons,” InSight Crime, 28 de noviembre de 2024 La violencia intestina estalló por primera vez en las prisiones, ejemplificada por las múltiples masacres de 2021.16James Bargent, “The prison system in Ecuador – History and challenges of an epicenter of crime,” InSight Crime, 12 de diciembre de 2024, pp.22-23 Después se extendió a las calles, desencadenando múltiples conflictos, desde los cuales Los Lobos han surgido como el principal perpetrador de violencia en su búsqueda por convertirse en un poder hegemónico en el mundo del crimen del país (véase gráfico a continuación).

El crecimiento de los grupos criminales y la intensificación de sus guerras territoriales hizo de Ecuador el país más violento de América Latina en 2023, con una tasa de homicidios de 44,5 homicidios por 100 000 habitantes, un récord que ha mantenido desde entonces.17Juliana Manjarrés y Christopher Newton, “InSight Crime’s 2023 Homicide Round-Up,” InSight Crime, 21 de febrero de 2024 En 2024, ACLED registra más eventos violentos en Ecuador que su vecina Colombia, un país aproximadamente cuatro veces más grande con casi el triple de población (véase el cuadro a continuación). La violencia relacionada con el crimen organizado ha afectado sobre todo a las provincias costeras, rampas de salida clave para los cargamentos de droga con destino a Norteamérica y Europa. Casi el 80 % de la violencia de grupos criminales registrada ha tenido lugar en cinco de las 24 provincias del país: Guayas, Manabí, El Oro, Santa Elena y Esmeraldas. La ciudad de Guayaquil, que alberga el mayor puerto del país y es crucial para los cargamentos de droga, es el foco de la violencia. Representa alrededor de una cuarta parte de los eventos de violencia del crimen organizado registrados hasta la fecha en Ecuador y se sitúa justo por detrás de Río de Janeiro y Salvador en Brasil en cuanto a número total de eventos relacionados con grupos criminales tanto en 2023 como en 2024 en toda América Latina (véase el cuadro a continuación).

| Violencia por parte de grupos armados no estatales en América Latina en 2024 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Por país | Por ciudad | ||

| País | Número de eventos | Ciudad | Número de eventos |

| 1. Brasil | 8,945 | 1. Rio de Janeiro, Brasil | 1,243 |

| 2. México | 7,191 | 2. Salvador, Brasil | 915 |

| 3. Ecuador | 2,389 | 3. Guayaquil, Ecuador | 570 |

| 4. Colombia | 2,157 | 4. Culiacán, México | 489 |

| 5. Venezuela | 465 | 5. León, México | 420 |

Sin embargo, la diversificación de la cartera económica de los grupos criminales ha impulsado su expansión hacia el interior, sobre todo alrededor de las áreas de explotación minera y a lo largo de las principales carreteras del país, que los grupos criminales utilizan para extorsionar a empresas exportadoras de productos agrícolas, textiles e industriales.18Entrevistas en línea con un experto en seguridad basada en Ecuador y con Renato Rivera, director del Observatorio Ecuatoriano de Crimen Organizado, ACLED, abril y mayo de 2025 De hecho, desde 2023, ACLED registra la presencia de grupos criminales en alrededor de dos tercios de los 222 cantones del país. Los Ríos, que conecta las provincias costeras con el centro del país, es la cuarta provincia más violenta. Los Ríos también está entre las provincias donde más aumentó la violencia del crimen organizado en 2024, junto con provincias andinas y amazónicas como Azuay, Tungurahua y Sucumbíos.

La confluencia de la política, las elecciones y la violencia criminal

La violencia del crimen organizado se ha entrelazado de manera intrínseca con la política y las elecciones en Ecuador. La seguridad es un tema central en los procesos políticos, ya que los resultados en ese ámbito afectan en gran medida la aprobación pública de los gobiernos, y los planes de seguridad son pilares fundamentales de las campañas electorales. La violencia también se ha convertido cada vez más en una característica de la competición política, ya que los grupos del crimen organizado se enfrentan a figuras políticas que obstaculizan sus intereses, siguiendo tendencias similares en otros países latinoamericanos como México, Brasil y Colombia.

Desde 2020, el deterioro de la situación de seguridad en Ecuador ha empañado la imagen del expresidente Guillermo Lasso, un conservador que, a finales de 2022, solo contaba con un 13 % de aprobación pública.19Voz de América, “Ecuador: La inseguridad lesiona la credibilidad del gobierno,” 29 de diciembre de 2022 Como resultado, las fuerzas de oposición vencieron a los partidos conservadores en las elecciones seccionales de febrero de 2023, y algunas reformas de seguridad propuestas por el gobierno fueron rechazadas en un referéndum.20Alexandra Valencia, “Ecuador’s Lasso accepts extradition referendum defeat; opposition wins mayoral races,” Reuters, 7 de fevrero de 2023 Una investigación periodística también encontró pruebas de la implicación de Lasso en tramas de malversación de fondos, así como vínculos entre su cuñado y la mafia albanesa. La investigación llevó a la Asamblea Nacional a iniciar un juicio político contra Lasso.21La Posta, “El Gran Padrino,” 9 de enero de 2023 Para evitarlo, Lasso disolvió la Asamblea Nacional en mayo de 2023 y convocó elecciones anticipadas.22Andrés Granadillo, “Ecuador: avanza solicitud de juicio político contra Lasso por presuntos delitos de corrupción,” France 24, 21 de marzo de 2023; Tom Phillips y Dan Collyns, “Ecuador’s embattled president dissolves congress in bid to avoid impeachment,” The Guardian, 17 de mayo de 2023 Noboa, un joven empresario que prometió una estrategia de mano dura contra el crimen, ganó la segunda vuelta de las elecciones contra la candidata de izquierda Luisa González en octubre de 2023 y fue nombrado para ocupar el cargo hasta el final del mandato de Lasso en mayo de 2025.23Dan Collyns, “Banana fortune heir Daniel Noboa wins Ecuador presidential election,” The Guardian, 16 de octubre de 2023

La inseguridad se mantuvo en el centro del debate público en el período previo a las elecciones de 2025: alrededor del 60 % de los entrevistados en una encuesta de finales de 2024 identificaron el crimen violento como el principal problema del país,24IPSOS, “Una Mirada Al 2024, ¿En quiénes confiaron los ecuatorianos y cuáles fueron sus principales preocupaciones en el 2024?” 31 de diciembre de 2024 y la mayoría de los candidatos presidenciales propusieron intervenciones militares y políticas más duras para combatir a las organizaciones criminales.25Steven Dudley, “How Organized Crime Set the Agenda for Ecuador’s Presidential Elections,” InSight Crime, 5 de febrero de 2025 Noboa, postulándose para la reelección, incluso propuso traer fuerzas extranjeras, incluyendo mercenarios, para ese propósito.26Abel Alvarado, David Culver y Barbara Arvanitidis, “Ecuador is preparing for US forces, plans show, as Noboa calls for help battling gangs,” CNN, 29 de marzo de 2025

Desde el ciclo electoral de 2023, la violencia no solo ha influenciado los desarrollos políticos sino que ha penetrado en la competición política. Entre 2018, cuando ACLED comenzó a cubrir Ecuador, y 2021, ocurrieron 30 eventos de violencia hacia funcionarios electos, trabajadores gubernamentales, candidatos y sus familiares, que resultaron en la muerte de cinco personas. Las cosas cambiaron en 2022: en el año previo a las elecciones seccionales del 5 de febrero de 2023, el número de eventos ascendió a 89 (véase el gráfico a continuación). Esta violencia se aceleró aún más durante las elecciones anticipadas de agosto: ACLED registra niveles similares de violencia en los cinco meses entre la convocatoria de Lasso de elecciones anticipadas y la segunda vuelta presidencial. Durante los dos procesos electorales, fueron asesinadas 99 personas en incidentes de violencia contra figuras políticas, incluido el candidato presidencial Fernando Villavicencio. La Fiscalía cree que miembros del grupo criminal Los Lobos llevaron a cabo su asesinato, pero aún no se ha identificado a los conspiradores del ataque.27Vanessa Buschschlüter, “Villavicencio murder ‘planned from jail’ by Los Lobos gang – prosecutors,” BBC, 28 de febrero de 2024

El impacto del conflicto armado interno en la adaptación y la fragmentación de los grupos criminales

La reelección de Noboa es un testimonio de la aprobación de la mayoría de los ecuatorianos a su política de seguridad, cuyas medidas más destacadas han sido la declaración de un conflicto armado interno, la repetida imposición de estados de excepción y la ampliación del papel de las fuerzas armadas en la seguridad pública. En 2024, la tasa de asesinato del país disminuyó ligeramente por primera vez desde 2019, aunque siguió siendo la más alta de América Latina.32Marina Cavalari, Juliana Manjarrés y Christopher Newton, “InSight Crime’s 2024 Homicide Round-Up,” InSight Crime, 26 de febrero de 2025 Sin embargo, las mismas medidas que contribuyeron a frenar la violencia en los primeros meses de 2024 —el aumento de la presión militar en las prisiones y en las calles— tuvieron la consecuencia no deseada de fomentar aún más las luchas de poder y la fragmentación dentro de los grupos del crimen organizado. Esto finalmente condujo a un recrudecimiento de la violencia a finales de año y a los cuatro meses más violentos jamás registrados en el país a principios de 2025.33Primicias, “Ecuador registró un 58% más de homicidios en el primer cuadrimestre de 2025,,” 21 de mayo de 2025

En enero de 2024, la política de seguridad de Noboa dio un giro hacia la militarización. Después de que el líder de Los Choneros escapara de la cárcel, Noboa anunció un estado de excepción en todo el país, al que los grupos criminales respondieron con una serie de ataques coordinados. Miembros del grupo criminal Los Tiguerones incluso llegaron a asaltar un estudio de televisión en Guayaquil.34Marita Moloney y Patrick Jackson, “Ecuador declares war on armed gangs after TV station attacked on air,” BBC, 10 de enero de 2024 En respuesta, Noboa declaró el 9 de enero un estado de conflicto armado interno, designando a 22 grupos del crimen organizado como ‘‘organizaciones terroristas’’ y encargando a las fuerzas armadas que participen en operaciones de seguridad en los barrios controlados por los grupos criminales y en los focos de minería ilegal, y de que asuman el control en las prisiones.35Las grupos criminales declarados grupos terroristas son: Águilas, ÁguilasKiller, Ak47, Caballeros Oscuros, ChoneKiller, Choneros, Covicheros, Cuartel de las Feas, Cubanos, Fatales, Gánster, Kater Piler, Lagartos, Latin Kings, Lobos, Los p.27, Los Tiburones, Mafia 18, Mafia Trébol, Patrones, R7, y Los Tiguerones. TeleSur English, “Noboa declares internal armed conflict in Ecuador,” 9 de enero de 2024 Aunque la Corte Constitucional dictaminó posteriormente que la situación en el país no cumplía los criterios para ser considerada un conflicto armado interno, el gobierno ha seguido utilizando el término para justificar la imposición de una serie de estados de excepción en todo el país o en provincias específicas.36Primicias, “La Corte Constitucional llama la atención a Noboa por insistir en la existencia del conflicto armado interno,” 2 de agosto de 2024 Esta medida aumentó la presión del gobierno y fue recibida con una resistencia severa por parte de los grupos criminales, que, en palabras de una experta en seguridad consultada para este informe, ‘‘se tomaron el concepto de conflicto armado interno más en serio que el propio gobierno, aumentando sus ataques’’.37Entrevista en línea con una experta en seguridad ecuatoriana, ACLED, 9 de abril de 2025 Como resultado, ACLED registra 58 eventos de violencia entre grupos criminales y fuerzas de seguridad en enero de 2024, siendo el 9 de enero el día más violento desde 2023.

A pesar de la reacción inmediata, el despliegue masivo de fuerzas militares tanto en las prisiones como en las calles tuvo un impacto temporal en las actividades de los grupos criminales, en particular sobre los enfrentamientos entre ellos y los ataques contra civiles en medio de las guerras entre grupos criminales (véase el gráfico a continuación). ACLED registra 128 eventos de violencia de grupos criminales en febrero, un 34 % menos que en enero y la más baja desde enero de 2023. Estos se mantuvieron en niveles relativamente bajos durante el resto del primer estado de excepción de tres meses. La violencia disminuyó dentro de las prisiones, escenario de varios brotes de violencia mortal en años anteriores. En el primer año desde que el 14 de enero las fuerzas militares tomaran el control del sistema penitenciario, los enfrentamientos entre grupos criminales y los ataques selectivos a presos por parte de miembros de esos grupos disminuyeron en un 64 % en comparación con el año anterior. Además, las muertes registradas como consecuencia de la violencia de los grupos criminales se redujeron en dos tercios, especialmente en la Penitenciaría de Guayaquil.

El aumento de las operaciones de las fuerzas de seguridad se tradujo en más enfrentamientos con los grupos criminales, dándose en muchos casos en el marco de rescates a personas que estaban siendo secuestradas. Pero estas operaciones no estuvieron exentas de críticas, ya que los militares también han sido acusados de graves violaciones de los derechos humanos, como el uso excesivo de la fuerza, desapariciones forzadas, violencia sexual y tortura.38Entrevista en línea con Billy Navarrete, director del Comité Permanente por la Defensa de los Derechos Humanos, ACLED, 2 de mayo de 2025 En 2024, las autoridades afirmaron haber detenido a más de 73 000 personas, pero la gran mayoría fueron puestas en libertad, en su mayoría por falta de pruebas.39Primicias, “Solo cuatro de cada 10 detenidos permanecieron en prisión en 2024, pese a proceso de militarización en Ecuador,” 2 de marzo de 2025 Mientras tanto, el Comité Permanente por la Defensa de los Derechos Humanos, con sede en Guayaquil, registra al menos 33 víctimas de desaparición forzada a manos de fuerzas estatales entre 2024 y 2025.40Comité Permanente por la Defensa de los Derechos Humanos, “Militarización no debe significar encubrimiento,” 24 de abril de 2025 En el caso quizá más perturbador, cuatro adolescentes fueron secuestrados y torturados por militares en Guayaquil el 8 de diciembre de 2024. Los restos de sus cuerpos fueron encontrados calcinados un par de semanas más tarde.41Tiago Rogero, “Ecuador confirms incinerated bodies belong to missing ‘Guayaquil Four’ boys,” The Guardian, 31 de diciembre de 2024 Una defensora de los derechos humanos consultada para este informe expresó su preocupación por el hecho de que estos hechos ocurrieran en medio de las reiteradas ofertas de Noboa de indultar a quienes cometan abusos.42Entrevistas en línea con una defensora de derechos humanos basada en Ecuador, ACLED, 4 April 2025; Yalilé Loaiza, “Daniel Noboa promised to pardon police officers and military personnel after the massacre in Guayaquil: ‘Defend Ecuador, and I will defend you,’” Infobae, 7 March 2025 (Spanish)

Pero la disminución a corto plazo de la violencia pronto se revirtió, ya que los grupos criminales se adaptaron a la nueva realidad y se fragmentaron cada vez más. A diferencia de Haití, donde los grupos criminales superaron antiguas rivalidades y formaron una alianza relativamente estable para luchar contra las fuerzas del Estado en septiembre de 2023, la oleada de ataques coordinados de grupos criminales contra las fuerzas de seguridad en Ecuador fue efímera y no se tradujo en una mayor cooperación. Por el contrario, las intervenciones en las prisiones y en las comunidades controladas por los grupos criminales dificultaron las comunicaciones entre los líderes encarcelados de los grupos y los líderes en libertad, y llevaron a algunos líderes a esconderse o incluso a abandonar el país, lo que desencadenó en luchas internas por el poder y a la creación de nuevos grupos criminales derivados.43Entrevista en línea con una experta en seguridad basada en Ecuador, ACLED, 11 de abril de 2025 ACLED registra actividad de al menos 37 grupos criminales en 2024, un 54 % más que en 2023, como parte de lo que un experto en seguridad denomina una ‘‘segunda ola de fragmentación’’, tras la que llevó a la desintegración de la confederación liderada por los Choneros.44Entrevista en línea con Renato Rivera, director del Observatorio Ecuatoriano de crimen organizado, ACLED, 13 de mayo de 2025 Por ejemplo, los líderes de los Chone Killers conocidos como Trompudo y Ben 10 fueron asesinados en Cali, Colombia, en diciembre de 2024, y se produjo una violenta competencia entre los líderes locales que dirigían los barrios de Durán, Guayas.45Primicias, “Tras crímenes de ‘Ben 10’ y ‘Trompudo Israel’, tres cabecillas de Chone Killers emergen como sus sucesores,” 30 de diciembre de 2024

Paralelamente, también se reanudó la competencia en las prisiones, ya que el control militar de éstas empezó a resquebrajarse en la segunda mitad del año y los grupos criminales intentaron recuperar el control de las economías carcelarias.46Entrevistas en línea con una experta en seguridad basada en Ecuador y Billy Navarrete, 11 de abril y 2 de mayo de 2025 El 12 de noviembre, una disputa entre los grupos criminales de Los Duendes y Los Freddy Krueger por el control de la distribución de alimentos provocó la muerte de al menos 17 presos en la Penitenciaría del Litoral.47Steven Dudley y James Bargent, “Jailhouse massacre in Ecuador illustrates rapid criminal evolution,” InSight Crime, 28 de noviembre de 2024

Más que nadie, la población civil ha pagado un alto precio por el resurgimiento de las actividades de los grupos criminales y sus disputas (véase el gráfico anterior). En muchos casos, los grupos criminales dirigen sus ataques hacia civiles que se niegan a pagar las extorsiones. En otros casos, estos eventos están relacionados con disputas territoriales. Según una experta en seguridad consultada por ACLED, un grupo suele atacar a civiles ‘‘para demostrar que el grupo contrario no tiene la capacidad para proteger a su gente, con el fin de sustituirlo y empezar a pedir pagos de extorsión más elevados’’.48Entrevista en línea con una funcionaria del gobierno de Ecuador, ACLED, 29 de agosto de 2024 Por ejemplo, el 7 de marzo de 2025, 22 personas fueron masacradas y al menos 120 familias fueron desplazadas forzosamente en el barrio Socio Vivienda de Guayaquil, como parte de la guerra entre las facciones Los Fénix y Los Igualitos de la banda Los Tiguerones, desencadenada por la captura de sus líderes en España en octubre de 2024.49Entrevista en línea con Renato Rivera, director del Observatorio Ecuatoriano de crimen organizado, ACLED, 13 de mayo de 2025; Al Jazeera, “At least 22 people killed as gang violence erupts in Ecuador,” 7 March 2025; Deborah Bonello y James Bargent, “Arrest of Leaders of Ecuador’s Tiguerones Could Further Fracture Gang,” InSight Crime, 23 de octubre 2024 Los sucesivos estados de excepción impuestos en las provincias y cantones más violentos no han conseguido frenar la violencia. Por el contrario, la violencia se recrudeció, tanto dentro como fuera de las prisiones, alcanzando niveles récord a principios de 2025.50Alexander García, “El primer trimestre de 2025, el más violento de la historia reciente de Ecuador,” Primicias, 21 de abril de 2025 Entre el 1 de enero y el 23 de mayo de 2025, ACLED registra más de 1 300 eventos de violencia del crimen organizado, más de un 60 % más que en el mismo periodo de 2024.

Lo que está por venir dependerá de los planes de Noboa, pero solo en parte

Noboa inicia su nuevo mandato en medio de una escalada de violencia del crimen organizado. A pesar de su victoria, abundan las dudas sobre si será capaz de sacar a Ecuador de esta crisis. Parte de esta titánica tarea dependerá de su política y de sus decisiones políticas; la otra parte dependerá de factores que escapan a su control.

A nivel interno, la militarización de Noboa desde principios de 2024 ha provocado la fragmentación de los grupos criminales y la rápida rotación de sus líderes. Para evitar un escenario como el de México, donde la escisión y las alianzas cambiantes de los grupos del crimen organizado han alimentado una constante escalada de violencia en las últimas décadas, necesitará un plan integral que vaya más allá del despliegue ad hoc y temporal de fuerzas armadas tanto en las prisiones como en las calles.51Entrevistas en línea con expertos en seguridad ecuatorianos, ACLED, abril y mayo de 2025; Steven Dudley, “Elected for a full term, Ecuador’s Noboa needs a plan,” InSight Crime, 14 de abril de 2025 Al mismo tiempo, Noboa se enfrenta a un panorama profundamente polarizado con una tenue mayoría en la Asamblea Nacional, lo que complica la gobernabilidad y la aprobación de reformas críticas,52Sebastian Jimenez, “Daniel Noboa consolidates power in Ecuador as regional right wing gains momentum,” CNN, 14 de abril de 2025 así como a una economía estancada, lo que limitará su margen de maniobra para ofrecer alternativas a la juventud desfavorecida del país.53The Economist, “Ecuador chooses a leader amid murder, blackouts and stagnation,” 6 de febrero de 2025 Mientras tanto, los intereses criminales siguen profundamente arraigados en los sectores político, judicial y de seguridad, a pesar de algunos esfuerzos por sacarlos a la luz y combatirlos. Los avances para erradicarlos dependerán del compromiso del próximo fiscal general que tendrá que ser nombrado, y de la voluntad del gobierno de colaborar con él.54Gavin Voss, “Corruption Sentences Pile Up in Ecuador, But Will It Matter?” InSight Crime, 21 de marzo de 2025

Pero el gobierno también tendrá que enfrentarse al hecho de que algunos de los principales motores de las economías ilícitas del país que los grupos criminales luchan ferozmente por controlar, como la cocaína y la minería ilegal de oro, están en auge. La producción de cocaína alcanzó niveles récord en 2023,55Oscar Medina, “Colombia’s Potential Cocaine Production Surges to a Record High,” Bloomberg, 19 de octubre de 2024 y las disputas de los grupos rebeldes colombianos por el control de los departamentos productores de coca del sur, Nariño y Putumayo, fronterizos con Ecuador, están lejos de terminar. Los cambios en las alianzas y el control territorial entre los grupos armados colombianos y ecuatorianos aumentan el riesgo de que aumente la violencia en ambos lados de la frontera. Al mismo tiempo, la subida mundial de los precios del oro ha desencadenado un auge de la minería ilegal, atrayendo a organizaciones criminales ecuatorianas, pero también colombianas, a las regiones amazónicas y andinas del país, lo que ha contribuido a aumentar la violencia contra las fuerzas de seguridad56France 24, “Ecuador declares national mourning for 11 troops killed by guerrillas,” 10 de mayo de 2025 y figuras políticas.57Arturo Torres y Dan Collyns, “In Ecuador, booming profits in small-scale gold mining reveal a tainted industry,” Mongabay, 3 de octubre de 2024; Gavin Voss, “Ecuador’s Lobos Turn El Oro Province Into Battleground,” InSight Crime, 27 de enero de 2025 Por último, la porosa frontera de 1 500 kilómetros de Ecuador con Perú ha facilitado el tráfico de armas desde el país vecino, que también está experimentando un deterioro de la seguridad.58Ojo Público, “Del Ejército peruano a las mafias del Ecuador: las rutas del tráfico de armamento en la frontera,” 14 de enero de 2024; Carla Álvarez, “¿EL PARAÍSO PERDIDO? TRÁFICO DE ARMAS DE FUEGO Y VIOLENCIA EN ECUADOR” Global Initiative against Transnational Organized Crime, junio de 2024, p.22

Abordar esta convergencia de desafíos de seguridad, económicos y políticos exigirá no solo una estrategia nacional coherente, sino también una sólida cooperación con los países vecinos y los aliados internacionales. Sus propuestas —que se basan en perpetuos estados de excepción, la construcción de nuevas prisiones de máxima seguridad y el aumento de las sanciones por delitos relacionados con el crimen organizdo— parecen inspirarse en gran medida en el manual de estrategia del presidente de El Salvador, Nayib Bukele. Pero aunque estas medidas asestaron un duro golpe a los grupos criminales de El Salvador, la suspensión del debido proceso y las miles de detenciones arbitrarias supusieron un enorme coste para los estándares democráticos del país.59Oliver Stuenkel, “Ecuador’s Challenge: Rout Organized Crime Without Endangering Democracy,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 18 de abril de 2025 A diferencia de su primera vez en el cargo, Noboa tiene ahora un mandato completo para elaborar una estrategia de seguridad que puede claramente inspirarse en ejemplos exitosos de la región, pero que necesita adaptarse a las especificidades criminales e institucionales del país. El período de cuatro años le da la oportunidad de lograr resultados más sustanciales, pero también hará más visible un fracaso.

Visuales por Ciro Murillo.

Contribución de la Universidad de Texas en Austin (UT)

Los datos utilizados en este informe fueron enriquecidos por el trabajo de los estudiantes de la Universidad de Texas en Austin (UT). Entre ellos se encuentran Ty Burroughs, Geraldyn Campos, Tamon Hamlett, Zee Khan y Noemi Mora, bajo la dirección de la Dra. Ashley Moran en el Departamento de Gobierno de la UT. La UT identificó y etiquetó eventos de desórdenes relacionados con las elecciones y eventos violentos dirigidos contra funcionarios públicos del nivel nacional en Ecuador entre enero de 2018 y agosto de 2024. El proyecto contribuye al seguimiento de la violencia hacia funcionarios y a la comprensión de sus manifestaciones en entornos políticos nacionales y subnacionales. Las etiquetas de desórdenes relacionados con las elecciones permiten el seguimiento de los disturbios que surgen durante los procesos electorales, como la violencia dirigida contra la infraestructura y los funcionarios electorales, las manifestaciones relacionadas con las elecciones (por ejemplo, reformas electorales, impugnación de resultados, etc.) y la violencia contra familiares de políticos, que es una herramienta utilizada con frecuencia por los agentes de poder para presionar a las figuras políticas.