Since the March 23 Movement (M23) began its advance in December 2024, taking over vast areas of the Democratic Republic of Congo’s North and South Kivu in a matter of months, other armed groups have exploited the upheaval to expand their operations. Violence committed by armed groups in the DRC, including the M23 and others, resulted in over 2,500 reported fatalities in the first three months of 2025, ACLED data show, though Congolese officials claim thousands more.1Olivia Le Poidevin, “Fighting in Congo has killed 7,000 since January, DRC prime minister says,” Reuters, 24 February 2025 Even by conservative fatality estimates, the first quarter of this year was the most fatal since 2002, when the country was embroiled in the Second Congo War.

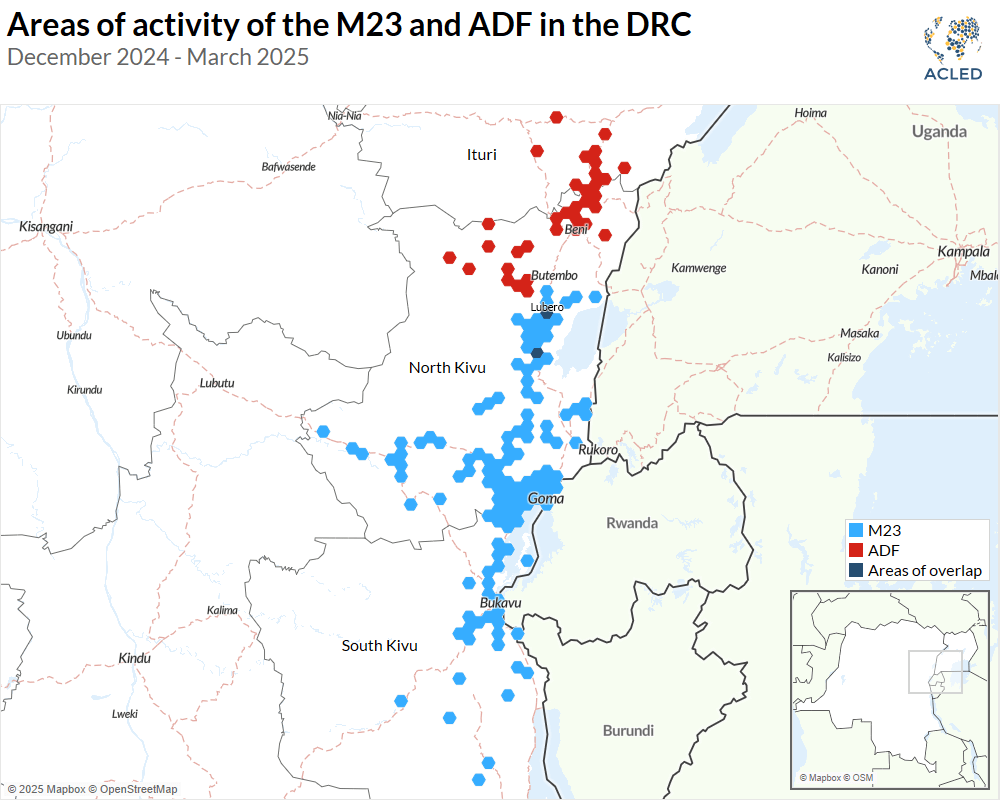

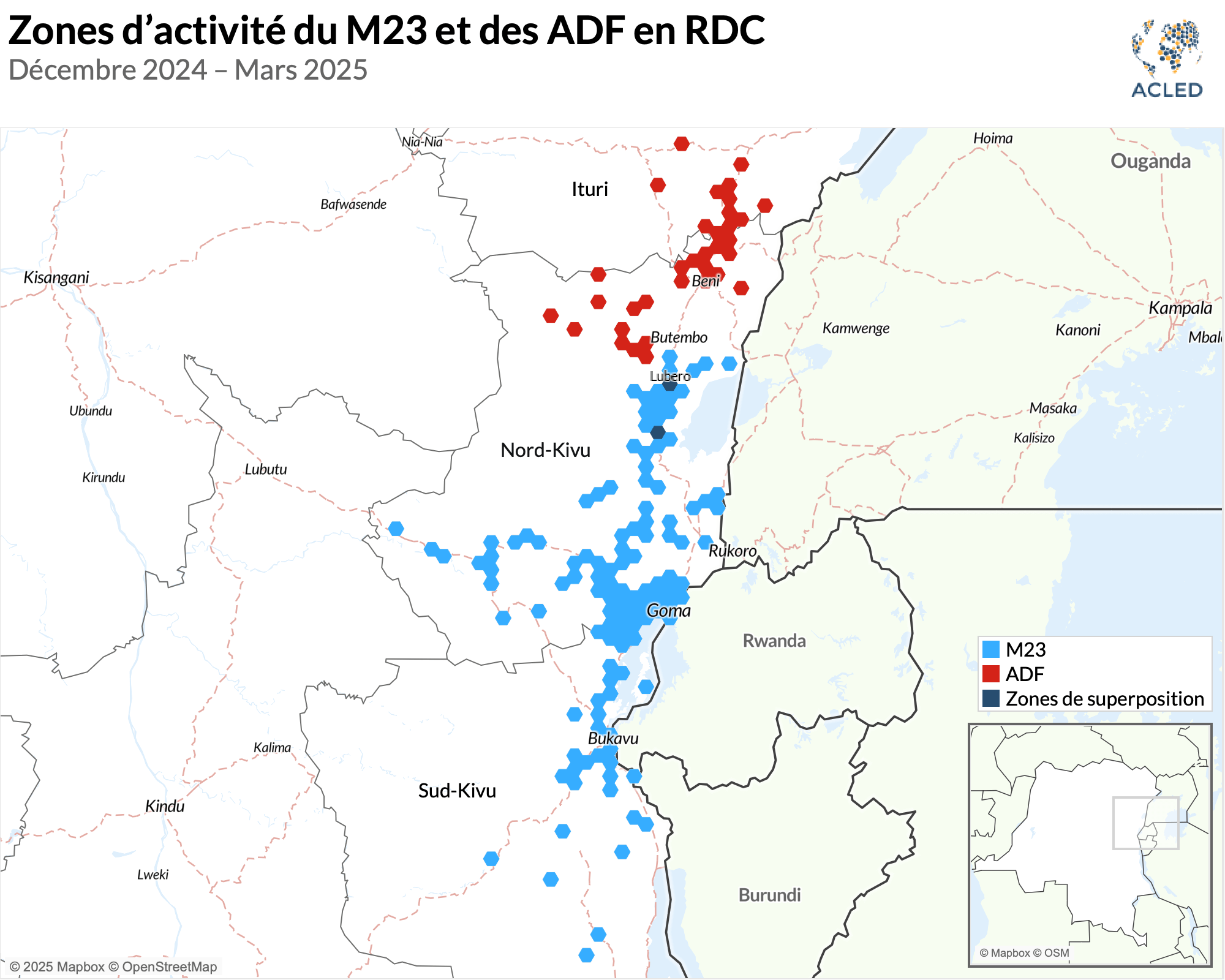

The M23 rebels’ northward advance in 2025 brings the group into an area of frequent incursions by the Allied Democratic Forces (ADF), an Islamist armed group with ties to the Islamic State (IS). While both the M23 and ADF have long been active in North Kivu province, the violence by each group was previously concentrated in geographically distinct areas: the M23 in the south and the ADF in the north. To proceed northward, the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) reported, the M23 rebels sought agreements with the ADF to avoid clashes between the two groups.2UNSC, “Letter dated 27 December 2024 from the Group of Experts on the Democratic Republic of the Congo addressed to the President of the Security Council,” S/2024/969, p. 27 December 2024; Actualite, “DRC: Contacts revealed between the AFC-M23 coalition and the ADF for a possible non-aggression pact,” 9 January 2025 Although denied by the M23, the UN report detailed that the ADF refused to form a non-aggression pact.3UNSC, “Letter dated 27 December 2024 from the Group of Experts on the Democratic Republic of the Congo addressed to the President of the Security Council,” S/2024/969, 27 December 2024, p. 9

While the M23 and ADF have yet to clash with one another, their simultaneous operations in geographically proximate areas have strained the Congolese military forces’ (FARDC) capacity to counter both groups simultaneously. As the FARDC tried to contain the M23 advance in the first quarter of 2025, its attention was diverted from the ADF, allowing the Islamist group to carry out a surge in civilian targeting.

Violence involving the ADF and M23 overlaps

Unlike the M23 rebellion, which receives backing from Rwanda and aims to overthrow the current Congolese administration,4For more on the M23, see The Resurgence and Alliances of the March 23 Movement (M23) the ADF swears allegiance to IS and is also known as the Islamic State Central Africa Province (ISCAP) in the eastern DRC and Uganda. Instead of replacing local authorities and forming alternative administrations like the M23, the ADF tends to use insurgent tactics to decimate local areas. Initially formed as a Ugandan rebel group in 1994 led by Jamil Mukulu, early ADF leadership and ideology arose from the Tabligh Muslim sect5Congo Research Group, “Inside the ADF Rebellion,” Center on International Cooperation at New York University, November 2018, p. 5 with intentions to overthrow Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni.6Lindsay Scorgie-Porter, “Economic Survival and Borderland Rebellion: The Case of the Allied Democratic Forces on the Uganda-Congo Border,” The Journal of the Middle East and Africa, 2015, pp. 195-201 Mukulu was arrested in 2015 and replaced by Musa Baluku. Baluku moved the group toward more extremist views of militant Islam,7Caleb Weiss, et al., “Rumble In The Jungle: ISCAP’s Rising Threat,” Hoover Institution, 6 June 2023 consolidated decision-making, and developed relations with IS — an integration Mukulu long resisted.8Tara Candland, et al., “The Rising Threat to Central Africa: The 2021 Transformation of the Islamic State’s Congolese Branch,” Combating Terrorism Center, June 2022; UNSC, “Letter dated 10 June 2021 from the Group of Experts on the Democratic Republic of the Congo addressed to the President of the Security Council,” S/2021/560, 10 June 2021, p. 8 By 2020, Baluku declared that the ADF had become ISCAP.9Emmanuel Mutaizibwa, “Inside the Lhubiriha, Kichwamba ADF attacks,” Monitor, 25 June 2023

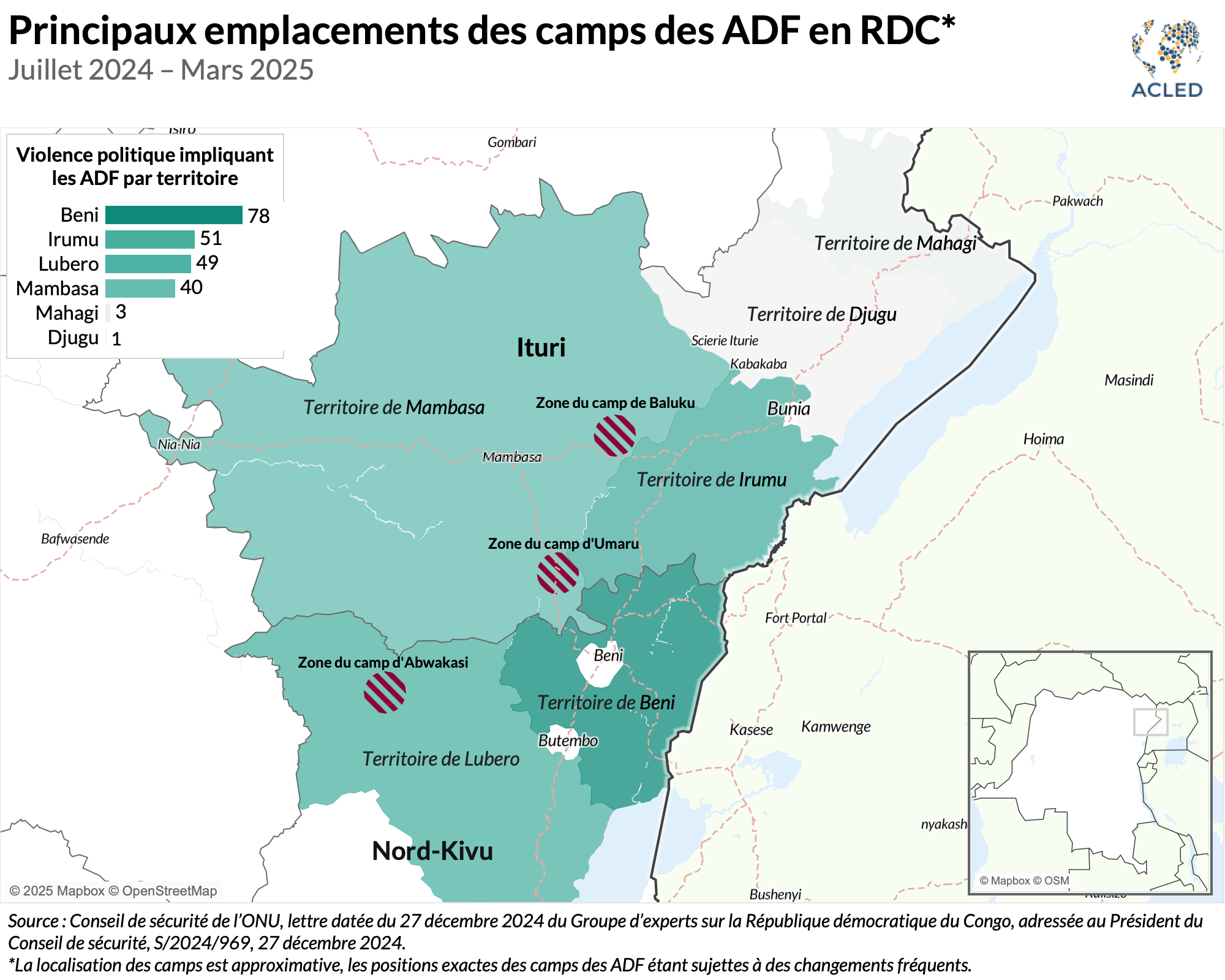

Starting from December 2024, the M23 and Rwandan military’s (RDF) northward push toward Lubero town in North Kivu brought the rebels into an area of frequent ADF violence (see map below). Lubero territory is a key area marking the northernmost advance of the M23-RDF so far in 2025, with Ugandan military (UPDF) positions north of Lubero town blocking further progress into Butembo or Beni towns. When the UPDF announced a potential withdrawal from the area in March, local civil society organized demonstrations and “dead city” protests in favor of continued UPDF occupation to defend Lubero from potential takeover by the M23-RDF.10Joel Kaseso, “In Butembo, social groups oppose the possible withdrawal of the UPDF from Lubero,” 7sur7, 31 March 2025

Before the M23 and RDF reached Lubero, the core areas of each group’s operations had remained separate. When these areas converged, what followed is illustrative of the risk of escalating insecurity through overlapping violence. On 9 January, the M23 and RDF fought together against the FARDC in Kaseghe, a town in Lubero territory. Just days later, on 11 January, the ADF took advantage of the FARDC’s instability as a result of the previous attack to carry out a violent attack in the same locality, reportedly killing 11 civilians. As numerous armed groups contend for power across the eastern DRC, the ADF has seized moments of FARDC weakness to increasingly move out of remote camps and carry out such civilian targeting.

While the ADF has long been based in the northern areas of North Kivu province — notably around Beni territory since the ADF shifted into the DRC from Uganda in the 1990s11Congo Research Group, “Inside the ADF Rebellion,” Center on International Cooperation at New York University, November 2018, p.6 — the ADF has also gradually moved northward toward Ituri province, with a notable escalation in operations since 2021. ADF violence in Ituri comprised only 11% of the group’s total violence in 2020, growing to 40% by the end of 2024. In both North Kivu and Ituri, the ADF also veered toward forested areas further west to avoid confrontations with military forces.12UNSC, “Letter dated 27 December 2024 from the Group of Experts on the Democratic Republic of the Congo addressed to the President of the Security Council,” S/2024/969, 27 December 2024, pp. 6 This westward movement notably shifted ADF violence in 2024 away from border areas near Uganda, with no violent incidents recorded within Ugandan territory last year.

ADF dealings with other armed groups

As the M23 sought to expand into new areas of the eastern DRC, the rebels attempted to forge agreements with the ADF. In December 2024, the UNSC reported that the M23 rebels sought agreements with the ADF to avoid clashes between the two groups as the M23 moved northward into Lubero territory and further toward Ituri province.13UNSC, “Letter dated 27 December 2024 from the Group of Experts on the Democratic Republic of the Congo addressed to the President of the Security Council,” S/2024/969, p. 27 December 2024; Actualite, “DRC: Contacts revealed between the AFC-M23 coalition and the ADF for a possible non-aggression pact,” 9 January 2025 Although the M23 denied they had made such a non-aggression pact, the UN report detailed that the ADF refused collaboration and would not agree to a non-aggression pact with the M23.14UNSC, “Letter dated 27 December 2024 from the Group of Experts on the Democratic Republic of the Congo addressed to the President of the Security Council,” S/2024/969, 27 December 2024, p. 9 Although the details of the M23’s proposed non-aggression pact with the ADF remain unclear, the ADF’s unwillingness to cooperate is consistent with its usual operations.

In March 2025, however, Ugandan military intelligence claimed that new alliances had been forged between the ADF and a coalition of Lendu militants, called the Cooperative for Development of the Congo (CODECO).15Chimp Reports, “UPDF Kills 242 CODECO Militants in Fierce Two-Day Battle in Eastern DRC,” 22 March 2025 A traditional chief in the Kasenye area of Lubero explained, “the ADF are no longer alone. Other armed groups with similar methods are operating in the shadows.”16Cédric Botela, “ADF Lubero 2025: 24 civilians massacred in 24 hours in North Kivu,” Congo Quotidien, 12 May 2025 (French) The ADF rarely collaborates with other armed groups and has struggled with internal schisms in recent years.17Caleb Weiss and Ryan O’Farrell, “PULI: Uganda’s Other (Short-lived) Jihadi Group,” The Long War Journal, 25 July 2023 The tendency for the ADF to operate alone also makes the Ugandan intelligence claim of ADF and CODECO collaboration a more novel development. If the two groups operate together, the partnership would be the first major ADF alliance since the demobilization of the National Army for the Liberation of Uganda (NALU) — a Ugandan rebel group — in 2007.18Congo Research Group, “Inside the ADF Rebellion,” Center on International Cooperation at New York University, November 2018, p.6

Joint Congolese and Ugandan military operations increase pressure on the insurgents

With the instability and disruptions involving the M23, the ADF initially faced reduced pressure in December 2024 and January 2025 as Congolese forces and allied armed groups focused on curbing the northward M23 offensive. Analysis of ACLED data indicates that territorial capture by the M23 in 2024 and so far in 2025 has an inverse relationship with the number of armed clashes involving the ADF (see graph below). This suggests that in months where the M23 captured additional territory, the Congolese forces and allies had limited capacity to also confront the ADF. This trend suggests the FARDC has limited capacity to confront both the ADF and M23 at the same time.

In response to the rising instability at its borders, Uganda deployed an additional 1,000 troops in February to Ituri and North Kivu, elevating the total number of Ugandan troops to around 5,000.19Economist Intelligence, “Uganda deploys additional troops to DRC,” 11 February 2025 Despite a lull in ADF violence since December 2024, the UPDF claimed that the ADF had moved westward into the densely forested areas of Ituri and North Kivu to avoid confrontation.20Geoffrey Omara, “UPDF Considers Withdrawing Forces from Lubero, Shifting Focus to North Kivu and Ituri,” Chimp Reports, 30 March 2025 In addition to the UPDF, Congolese authorities increasingly recruited and encouraged allied armed groups to support security efforts against the ADF. These include local self-defense militias and Wazalendo — a loose coalition of armed groups that began as youth self-defense militias but has expanded with a growing number of members since the resurgence of the M23.21UNSC, “Letter dated 27 December 2024 from the Group of Experts on the Democratic Republic of the Congo addressed to the President of the Security Council,” S/2024/969, Annex 10

Despite the deployment of additional Ugandan forces and allied militias, the ADF has effectively evaded clashes in the first quarter of 2025. ACLED records only five clashes involving the ADF between January and March 2025, less than 25% of the quarterly average number of battles involving the ADF in 2024.

The recent Ugandan military pressure on the ADF stems from the ongoing Operation Shujaa, a multinational counterterrorism operation spearheaded by Ugandan and Congolese forces since 2021. During the course of Operation Shujaa, joint forces have been destroying numerous ADF camps and forcing the ADF to frequently change locations to avoid confrontations with soldiers,22Africa Defence Forum, “Joint Military Operations Take Out Two Terror Figures in Eastern DRC,” 30 April 2024 limiting the ADF’s ability to re-establish long-term bases.23UNSC, “Letter dated 13 June 2023 from the Group of Experts on the Democratic Republic of the Congo addressed to the President of the Security Council,” S/2023/431,13 June 2023 Operation Shujaa has been effective in reducing overall levels of ADF violence, but has struggled to curb civilian targeting. Overall, ADF violence peaked in 2021 and has declined each year that followed during the course of Operation Shujaa.

The ADF’s camp structure shifts to respond to pressure

Under the increasing pressure of Operation Shujaa, the ADF was forced to adapt its operational structures. Each camp functions as a unit of the ADF, and all major operations must be reported to Baluku as the overall leader of the group.24UNSC, “Letter dated 27 December 2024 from the Group of Experts on the Democratic Republic of the Congo addressed to the President of the Security Council,” S/2024/969, 27 December 2024, p. 7 ADF camps are composed of both militants and their families, along with captured civilians, frequently using more mobile structures such as tents as shelters.25Andrew Bagala, “UPDF capture main ADF base,” Daily Monitor Uganda, 27 December 2021 The ADF uses the camps as a site for habitation, training, communication of IS ideology, construction of explosives, and weapons storage.26Basaija Idd, “ADF Camp Capture, a Milestone Against Terrorism-UPDF,” Uganda Radio Network, 27 December 2021; Ryan O’Farrell, et al., “Clerics in the Congo: Understanding the Ideology of the Islamic State in Central Africa,” Hudson Institute, 11 April 2024 Some camps, such as the previously captured Kambi Ya Yua, have been as large as eight acres and feature more semi-permanent structures such as fences and booths made from local materials.27Basaija Idd, “ADF Camp Capture, a Milestone Against Terrorism-UPDF,” Uganda Radio Network, 27 December 2021

Faced with the joint military operations since 2021, the ADF initially split into at least six camps under different commanders to permit increased mobility and decreased risk of detection.28UNSC, “Letter dated 27 December 2024 from the Group of Experts on the Democratic Republic of the Congo addressed to the President of the Security Council,” S/2024/969, 27 December 2024, pp. 6-7 The ADF camps have used different tactics vis à vis other armed groups and the civilian population, changing location frequently to avoid confrontation with Congolese and Ugandan military forces.

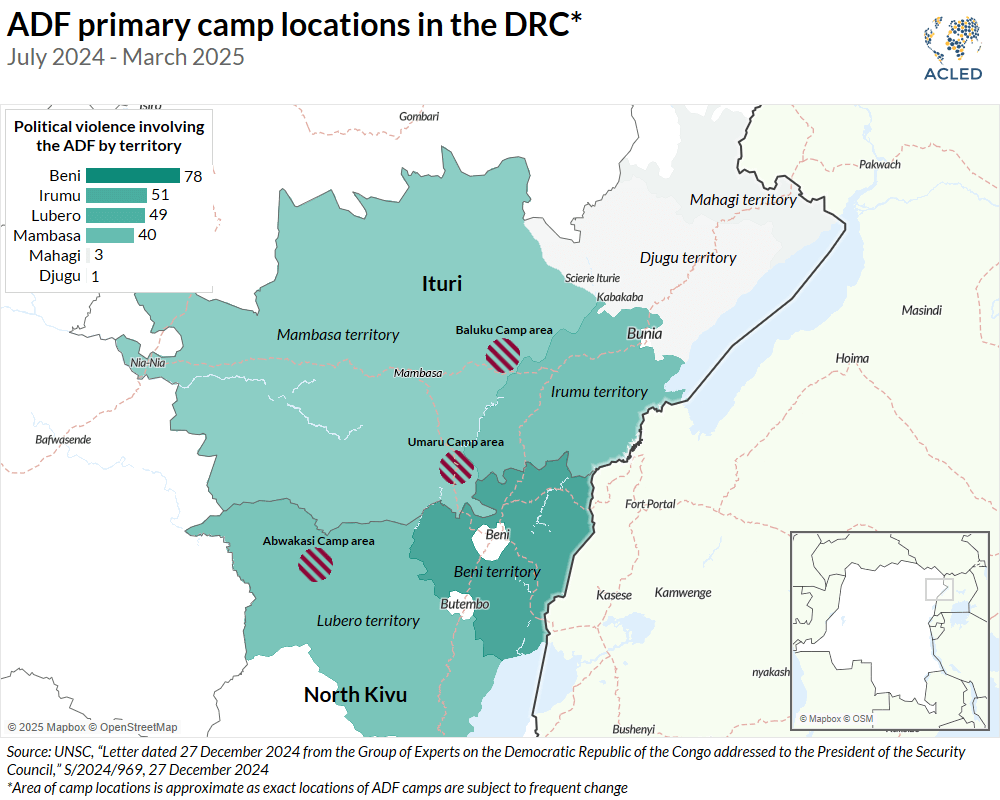

By mid-2024, the ADF consolidated its camps from six to three and moved them into more remote areas to provide sufficient defenses against Congolese and Ugandan forces (see map below).29Kim Aine, “ADF Strikes Again in Eastern Congo, Civilians Bear the Brunt,” Chimp Reports, 17 January 2025; UNSC, “Letter dated 27 December 2024 from the Group of Experts on the Democratic Republic of the Congo addressed to the President of the Security Council,” S/2024/969, 27 December 2024, p. 7 By increasing the number of militants in fewer camps, the ADF has attempted to better defend itself during clashes with Congolese and Ugandan soldiers.

Baluku commands the largest camp of approximately 1,000 people, commonly known as Madina.30UNSC, “Letter dated 27 December 2024 from the Group of Experts on the Democratic Republic of the Congo addressed to the President of the Security Council,” S/2024/969, 27 December 2024, p. 7 This camp is located near Lolwa, to the north of the Ituri River in Mambasa territory.31Actualite, “DRC: ADF responsible for more than 650 deaths in Ituri and North Kivu since June,” 12 January 2025 After facing increasing pressure in 2024, the Madina camp has tried to avoid confrontations with the Congolese and Ugandan militaries so far in 2025, with ACLED recording only three violent events between January and May.

By the end of the first quarter in 2025, the M23-RDF offensive had reached an ADF camp in Lubero territory under the leadership of Ahmad Mahmood Hassan, who is commonly called Abwakasi.32UNSC, “Ahmad Mahmood Hassan,” 21 April 2025 Abwakasi, a Tanzanian national who frequently appears in ADF media, is known for his capacity to build explosives and likely orchestrated the 2023 killing of 38 school children at Mpondwe-Lhubiriha Secondary School in Uganda.33Jacob Zenn, “Abuwakas: The Arab–Tanzanian Face of Islamic State’s Jihad in the Congo,” Jamestown Foundation, 7 September 2023 The camp under Abwakasi’s command was the most deadly toward civilians in the past year. Civilian fatalities by the ADF in Lubero — the area under Abwakasi — account for over 40% of the total number of reported civilian fatalities by the ADF since mid-2024.

The third ADF camp, which is under the leadership of Seka Umaru, has been operating in the area northwest of Oicha. UN experts describe Seka Umaru as Baluku’s second-in-command and potential successor.34Actualite, “ADF still in control of Baluku, Daesh intensifies its demands in the DRC, according to the UN,” 12 January 2025 Umaru joined the ADF after the departure of former leader Mukulu in 2014 and was an early advocate for allegiance to IS Central.35Ryan O’Farrell, et al., “Clerics in the Congo: Understanding the Ideology of the Islamic State in Central Africa,” Hudson Institute, 11 April 2024

ADF violence increasingly kills more civilians

The ADF has generally been able to avoid direct confrontations with Congolese and Ugandan forces so far in 2025, with battles involving the ADF declining. As the M23 took control of vast tracts of North Kivu and South Kivu in the first quarter of 2025, the ADF used the disruption to authority caused by the Congolese military’s diverted focus on limiting the M23 rebellion to carry out a string of deadly attacks against civilians. As a result, civilian fatalities rose by 68% in the first quarter of 2025 compared to the previous quarter — the second-deadliest quarter of civilian targeting by the ADF since ACLED began recording data on the group in 1997.

ACLED records at least 450 fatalities by the ADF in the first quarter of 2025, exclusively among unarmed civilians, including the abduction and mass killing of 70 people at a church in the Lubero territory on 11 February. This followed simultaneous attacks on five localities in Lubero on 15 January that reportedly led to at least 112 fatalities. Together, these attacks led to 15% more civilian targeting incidents in the first quarter of 2025 than in the final quarter of 2024.

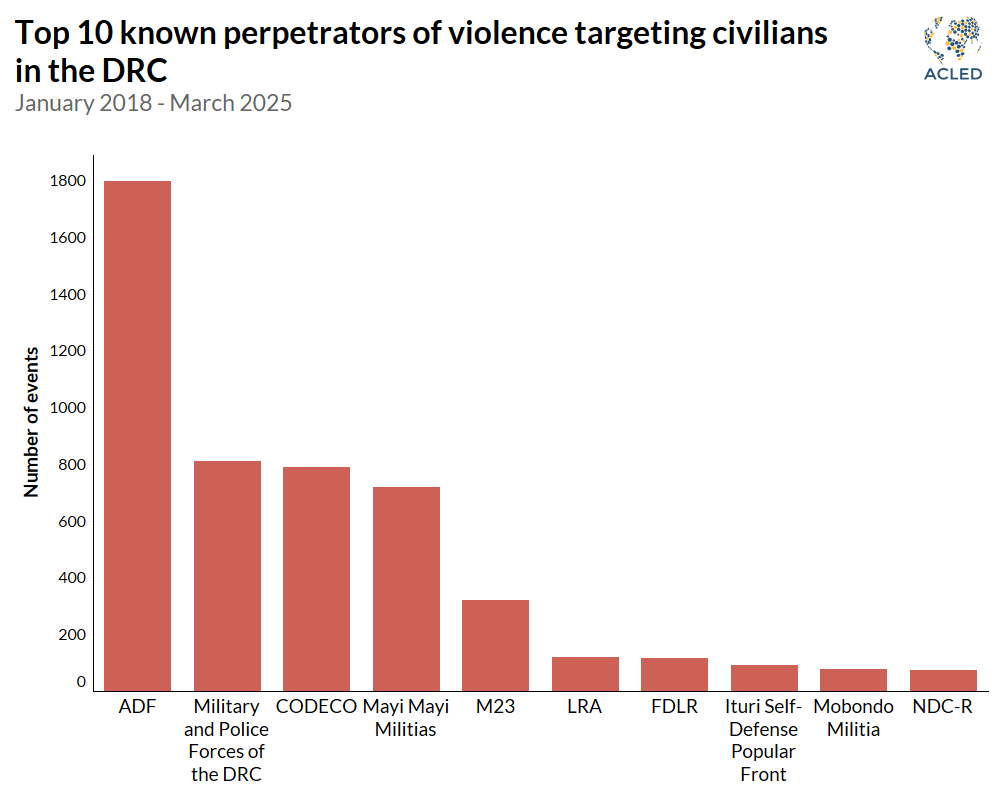

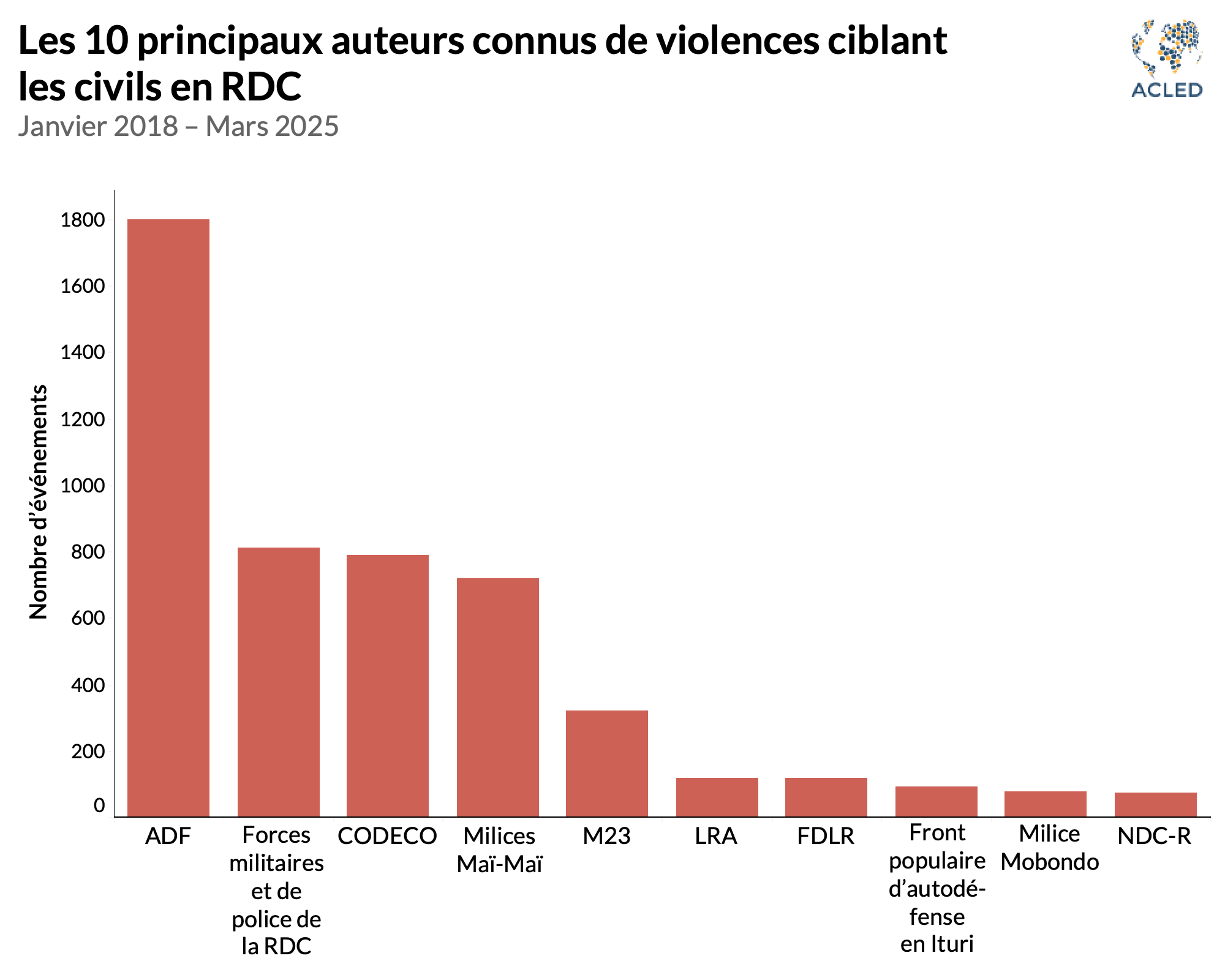

Civilian targeting by the ADF not only increased in the first quarter of 2025, but it also became increasingly deadly. Like other IS affiliates, the ADF tends to carry out high levels of civilian targeting each year and has been the most violent actor toward civilians in the DRC since 2018 (see graph below). Compared to other IS affiliates, the ADF was the most violent group toward civilians in 2024. In fact, attacks by the group resulted in 2024 being the deadliest year of civilian targeting by the ADF under the leadership of Baluku, with over 1,600 reported civilian fatalities. Instead of trying to usurp local authorities and govern areas of the eastern DRC, the ADF tends to devastate areas through mass killings, extensive looting, kidnapping for ransom, and setting property ablaze.

The ADF shares photos and videos of such brutality through their own media channels and via IS Central.36UNSC, “Letter dated 27 December 2024 from the Group of Experts on the Democratic Republic of the Congo addressed to the President of the Security Council,” S/2024/969, 27 December 2024, Annex 9; For example, see X @WerbCharlie, 4 April 2025; X @War_Noir, 6 March 2025 In exchange for the IS affiliation and media of violence frequently framed against “Christians,” “crusaders,” or “infidels,”37UNSC, “Letter dated 27 December 2024 from the Group of Experts on the Democratic Republic of the Congo addressed to the President of the Security Council,” S/2024/969, 27 December 2024, Annex 9; For example, see X @WerbCharlie, 4 April 2025; X @War_Noir, 6 March 2025 the ADF receives funding, notoriety, and training from IS, especially through their regional network in eastern and southern Africa stretching from Somalia to South Africa.38Caleb Weiss, et al., “Rumble In The Jungle: ISCAP’s Rising Threat,” Hoover Institution, 6 June 2023 Since mid-2024, IS Central has increasingly posted media about the ADF’s operations, with a quicker turnaround between the time of the attack and the time the post is published by IS Central.

As IS Somalia increases as a hub of the group’s global operations,39Mustafa Hasan, “Somalia: The New Frontline in the Islamic State’s Global Expansion,” Washington Institute, 27 February 2025 the ADF is likely benefiting from the increased attention of IS throughout Africa. With the additional finances and training of IS Central, the relationship permits the ADF to operate not through generating positive relations with local populations, but by generating external legitimacy from IS Central through brutal violence against civilians.

The relationship with IS Central has also opened up the resources and training to build and carry out explosive attacks and, more recently, operate drones. Each of the ADF camps possesses a limited number of drones, primarily used for surveillance and avoiding direct confrontations.40UNSC, “Letter dated 27 December 2024 from the Group of Experts on the Democratic Republic of the Congo addressed to the President of the Security Council,” S/2024/969, 27 December 2024, Annex 5 The ADF initiated its first attempted use of an explosive carried by a drone on 11 August 2024 against Congolese soldiers in Malyajama, Beni territory. The explosive device failed to detonate, but the incident shows the ADF’s capacity to use such techniques in the future.

The ADF capitalizes on regional instability

To combat the M23, the FARDC will likely need to further deploy its military forces to the northern frontlines in Lubero territory. This will open up new areas for the ADF and other armed groups to operate with less resistance. Despite the challenges for the FARDC, the Ugandan military has been ambitious in 2025 to place increased pressure on the ADF and other armed groups in Ituri, notably CODECO.41David Ajuna and Felix Okello, “How top army commander died as UPDF killed 242 militants in DR Congo battle,” Monitor, 22 March 2025

The Ugandan government likely fears the possibility that the ADF will move closer to the Ugandan border with the FARDC distracted elsewhere, especially with the ADF’s proclivity for conducting cross-border attacks into Ugandan territory. However, the UPDF on its own will likely prove insufficient to deter violence by the ADF. In addition to the UPDF, the FARDC will also likely need to rely on other local armed groups and self-defense militias to control localities and guard against future ADF attacks.

If Ugandan and Congolese militaries are unable to sustain their continuing pressure on the ADF, this would likely enable the ADF to regroup and adjust its own strategies. The ADF’s frequent scorched-earth tactics may shift to more stationary extraction of resources. Already in April 2025, the ADF engaged in revenue generation that indicates an intention to hold territory for longer periods, using purported “taxes” on civilians and controlling mining sites.42Radio Okapi, “Lubero: ADF accused of using Bapere populations for illegal gold mining,” 14 April 2025; Radio Okapi, “ADF rebels impose taxes on Congolese farmers in Mutweyi,” 17 April 2025 In recent years, these forms of local revenue generation have been uncommon for the ADF, which tends to plunder areas and leave rather than engage in more long-term relations with civilians.

The instability generated by the M23 rebellion and concurrent ADF operations in North Kivu has displaced thousands and already led to over 1,600 reported fatalities in the province in the first three months of 2025.43Joshua Mutanava, “Lubero: In Biena, health facilities are struggling to function due to the activism of ADF rebels,” Actualite, 12 April 2025 In the coming months, the ceasefire agreements between Rwanda and the DRC are unlikely to reduce overall violence in the eastern DRC but will probably shift violence to other armed groups who will continue taking advantage of the instability to strengthen their own position in the region. The conflict with the M23 has required the FARDC to pivot attention away from the ADF, which may permit the ADF to increase deadly civilian attacks in the second half of 2025. Despite a relative lull in the M23 rebellion, the ensuing collapse of authority has provided ample opportunities for the ADF to entrench its presence in the eastern DRC, exposing the local civilian population to the effects of mass violence.

Visuals produced by Christian Jaffe.

Alors que les rebelles du M23 prennent le contrôle de l’est du Congo, l’État islamique exploite le chaos

Depuis que le Mouvement du 23 Mars (M23) a commencé son avancée en décembre 2024, s’emparant en quelques mois de vastes zones des provinces du Nord et du Sud Kivu en République démocratique du Congo (RDC), d’autres groupes armés ont tiré parti du chaos pour étendre leurs opérations. Selon les données d’ACLED, la violence perpétrée par les groupes armés en RDC, dont le M23, a causé plus de 2 500 décès au cours du premier trimestre 2025, bien que les autorités congolaises avancent un bilan bien plus élevé.1Olivia Le Poidevin, “Fighting in Congo has killed 7,000 since January, DRC prime minister says,” Reuters, 24 février 2025 Même selon les estimations les plus prudentes, ce trimestre est le plus meurtrier depuis 2002, date à laquelle le pays était plongé dans la Deuxième guerre du Congo.

L’avancée des rebelles du M23 vers le nord en 2025 les a conduits dans une zone régulièrement en proie à des incursions des Forces démocratiques alliées (ADF), un groupe armé islamiste affilié à l’État islamique (EI). Bien que le M23 et les ADF soient actifs depuis longtemps dans la province du Nord-Kivu, la violence exercée par chacun de ces groupes était jusqu’alors concentrée dans des zones géographiques distinctes : le M23 au sud et les ADF au nord.

Pour progresser vers le nord, les rebelles du M23 ont, selon un rapport du Conseil de sécurité des Nations Unies (CSNU), cherché à conclure des accords avec les ADF afin d’éviter des affrontements entre les deux groupes.2UNSC, “Letter dated 27 December 2024 from the Group of Experts on the Democratic Republic of the Congo addressed to the President of the Security Council,” S/2024/969, p. 27 décembre 2024; Actualite, “DRC: Contacts revealed between the AFC-M23 coalition and the ADF for a possible non-aggression pact,” 9 janvier 2025 Bien que cela ait été démenti par le M23, le rapport de l’ONU précise que les ADF ont refusé de conclure un pacte de non-agression.3UNSC, “Letter dated 27 December 2024 from the Group of Experts on the Democratic Republic of the Congo addressed to the President of the Security Council,” S/2024/969, 27 décembre 2024, p. 9 Même si le M23 et les ADF ne se sont pas encore affrontés directement, leurs opérations simultanées dans des zones géographiquement proches ont mis à rude épreuve les capacités des Forces armées de la République démocratique du Congo (FARDC), qui peinent à contrer les deux menaces en parallèle. Alors que les FARDC tentaient de contenir l’avancée du M23 au premier trimestre 2025, leur attention a été détournée des ADF, ce qui a permis au groupe islamiste d’intensifier ses attaques contre les civils.

Une superposition des violences impliquant les ADF et le M23

Contrairement à la rébellion du M23, qui bénéficie du soutien du Rwanda et dont l’objectif est de renverser l’actuel gouvernement congolais,4Pour en savoir plus sur le M23, voir La résurgence et les alliances du Mouvement du 23 mars (M23). les ADF ont prêté allégeance à l’État islamique (EI) et sont également connus sous le nom de Province de l’État islamique en Afrique centrale (ISCAP) dans l’est de la RDC et en Ouganda. Alors que le M23 cherche à remplacer les autorités locales et à instaurer des structures administratives alternatives, les ADF ont plutôt recours à des tactiques insurrectionnelles pour ravager les zones locales. Formés à l’origine en 1994 comme groupe rebelle ougandais dirigé par Jamil Mukulu, les ADF, notamment à travers leurs premiers dirigeants, puisaient initialement leur idéologie dans le courant musulman Tabligh,5Congo Research Group, “Inside the ADF Rebellion,” Center on International Cooperation at New York University, novembre 2018, p. 5 avec pour objectif le renversement du président ougandais Yoweri Museveni.6Lindsay Scorgie-Porter, “Economic Survival and Borderland Rebellion: The Case of the Allied Democratic Forces on the Uganda-Congo Border,” The Journal of the Middle East and Africa, 2015, pp. 195-201 L’arrestation de Mukulu en 2015 a conduit à son remplacement par Musa Baluku, lequel a orienté le groupe vers une vision plus radicale de l’islam militant,7Caleb Weiss, et al., “Rumble In The Jungle: ISCAP’s Rising Threat,” Hoover Institution, 6 juin 2023 centralisé le processus décisionnel et établi des liens avec l’EI, alors que Mukulu s’y était toujours opposé.8Tara Candland, et al., “The Rising Threat to Central Africa: The 2021 Transformation of the Islamic State’s Congolese Branch,” Combating Terrorism Center, June 2022; UNSC, “Letter dated 10 June 2021 from the Group of Experts on the Democratic Republic of the Congo addressed to the President of the Security Council,” S/2021/560, 10 juin 2021, p. 8 En 2020, Baluku a déclaré que les ADF formaient désormais la Province de l’État islamique en Afrique centrale (ISCAP).9Emmanuel Mutaizibwa, “Inside the Lhubiriha, Kichwamba ADF attacks,” Monitor, 25 juin 2023

À partir de décembre 2024, la progression vers le nord du M23 et des Forces de défense rwandaises (RDF) en direction de la ville de Lubero, dans le Nord-Kivu, a conduit les rebelles du M23 dans une zone déjà marquée par des violences récurrentes perpétrées par les ADF (voir carte ci-dessous). Le territoire clé de Lubero constitue aujourd’hui le point le plus au nord atteint par l’offensive conjointe du M23 et des RDF en 2025. Les positions de l’armée ougandaise (UPDF) situées au nord de la ville de Lubero bloquent pour l’instant toute progression du M23 et des RDF vers les villes de Butembo et de Beni. Lorsque les UPDF ont annoncé un possible retrait de la zone en mars, la société civile locale a organisé des manifestations et des journées « ville morte » en faveur du maintien des troupes ougandaises pour défendre le Lubero face à une possible prise de contrôle par le M23 et les RDF.10Joel Kaseso, “In Butembo, social groups oppose the possible withdrawal of the UPDF from Lubero,” 7sur7, 31 mars 2025

Avant que le M23 et les RDF n’atteignent le territoire de Lubero, les zones principales d’opération des deux groupes étaient distinctes. Leur convergence récente et les événements qui ont suivi illustrent bien le risque d’une insécurité croissante due à la superposition des violences. Le 9 janvier, le M23 et les RDF ont combattu ensemble les FARDC à Kaseghe, une ville située dans le territoire de Lubero. Quelques jours plus tard, le 11 janvier, les ADF ont profité de la déstabilisation de l’armée congolaise, affaiblie par l’affrontement précédent, pour mener une attaque meurtrière dans cette même localité, tuant 11 civils selon les estimations. Alors que de nombreux groupes armés se disputent le pouvoir dans l’est de la RDC, les ADF exploitent les moments de faiblesse des FARDC pour quitter leurs camps isolés et intensifier les attaques contre les civils.

Historiquement basés dans les régions septentrionales du Nord-Kivu — notamment autour du territoire de Beni, depuis leur repli de l’Ouganda vers la RDC dans les années 199011Congo Research Group, “Inside the ADF Rebellion,” Center on International Cooperation at New York University, novembre 2018, p.6 — les ADF ont progressivement étendu leurs opérations vers le nord en direction de la province de l’Ituri, avec une intensification marquée de celles-ci depuis 2021. En 2020, la violence des ADF en Ituri ne représentait que 11 % des violences totales attribuées au groupe. Elle est passée à 40 % à la fin de l’année 2024. Dans les deux provinces, Nord-Kivu et Ituri, les ADF se sont également déplacés vers des zones boisées plus à l’ouest afin d’éviter les affrontements avec les forces armées.12UNSC, “Letter dated 27 December 2024 from the Group of Experts on the Democratic Republic of the Congo addressed to the President of the Security Council,” S/2024/969, 27 décembre 2024, pp. 6 Ce déplacement vers l’ouest a notamment éloigné les violences commises par les ADF des zones frontalières proches de l’Ouganda en 2024. Aucun incident violent impliquant les ADF n’a été enregistré sur le territoire ougandais en 2024.

Les relations des ADF avec d’autres groupes armés

Alors que le M23 cherchait à s’étendre dans de nouvelles zones de l’est de la RDC, les rebelles ont tenté de conclure des accords avec les ADF. En décembre 2024, le Conseil de sécurité des Nations Unies (CSNU) a rapporté que les rebelles du M23 avaient cherché à s’entendre avec les ADF afin d’éviter des affrontements entre les deux groupes, au moment où le M23 avançait vers le nord, dans le territoire de Lubero, et poursuivait sa progression vers la province de l’Ituri.13UNSC, “Letter dated 27 December 2024 from the Group of Experts on the Democratic Republic of the Congo addressed to the President of the Security Council,” S/2024/969, p. 27 December 2024; Actualite, “DRC: Contacts revealed between the AFC-M23 coalition and the ADF for a possible non-aggression pact,” 9 janvier 2025 Bien que le M23 ait nié l’existence d’un tel pacte de non-agression, le rapport de l’ONU précise que les ADF ont refusé toute forme de collaboration et décliné toute proposition d’accord.14UNSC, “Letter dated 27 December 2024 from the Group of Experts on the Democratic Republic of the Congo addressed to the President of the Security Council,” S/2024/969, 27 décembre 2024, p. 9 Si les détails du pacte proposé restent flous, le refus des ADF s’inscrit dans la continuité de leur mode opératoire habituel.

Cependant, en mars 2025, les services de renseignement militaire ougandais ont affirmé que de nouvelles alliances avaient été nouées entre les ADF et une coalition de miliciens Lendu, connue sous le nom de Coopérative pour le développement du Congo (CODECO).15Chimp Reports, “UPDF Kills 242 CODECO Militants in Fierce Two-Day Battle in Eastern DRC,” 22 mars 2025 Un chef traditionnel de la région de Kasenye, dans le territoire de Lubero, a déclaré : « Les ADF ne sont plus seuls. D’autres groupes armés aux méthodes similaires opèrent dans l’ombre. 16Cédric Botela, “ADF Lubero 2025 : 24 civils massacrés en 24 heures dans le Nord-Kivu,” Congo Quotidien, 12 mai 2025» Les ADF collaborent rarement avec d’autres groupes armés et ont été confrontés à des divisions internes ces dernières années.17Caleb Weiss and Ryan O’Farrell, “PULI: Uganda’s Other (Short-lived) Jihadi Group,” The Long War Journal, 25 juillet 2023 Leur tendance à agir de manière autonome confère un caractère inédit aux affirmations des services de renseignement ougandais sur une collaboration entre les ADF et la CODECO. Si une telle coopération se confirmait, elle constituerait la première alliance majeure pour les ADF depuis la démobilisation, en 2007, de l’Armée nationale de libération de l’Ouganda (NALU), un groupe rebelle ougandais.18Congo Research Group, “Inside the ADF Rebellion,” Center on International Cooperation at New York University, novembre 2018, p.6

Les opérations militaires conjointes entre la RDC et l’Ouganda accentuent la pression sur les insurgés

En raison de l’instabilité et des perturbations liées aux activités du M23, les ADF ont d’abord bénéficié d’un allègement de la pression en décembre 2024 et janvier 2025, les forces congolaises et les groupes armés alliés concentrant alors leurs efforts pour endiguer l’offensive du M23 vers le nord. L’analyse des données d’ACLED indique que les conquêtes territoriales du M23, en 2024 et jusqu’à présent en 2025, sont inversement proportionnelles au nombre d’affrontements armés impliquant les ADF (voir graphique ci-dessous). Cela suggère qu’au cours des mois où le M23 s’emparait de nouvelles zones, les forces congolaises et leurs alliés disposaient de capacités limitées pour affronter les ADF. Cette tendance met en lumière les capacités restreintes des FARDC à affronter simultanément les ADF et le M23.

En réaction à l’instabilité croissante à proximité de ses frontières, l’Ouganda a déployé en février 2025 un millier de soldats supplémentaires en Ituri et au Nord-Kivu, portant ses effectifs totaux sur le terrain à environ 5 000 soldats.19Economist Intelligence, “Uganda deploys additional troops to DRC,” 11 février 2025 Bien qu’un ralentissement des violences attribuées aux ADF soit observé depuis décembre 2024, les UPDF ont affirmé que le groupe s’était replié vers l’ouest, dans les zones densément boisées de l’Ituri et du Nord-Kivu, afin d’éviter tout affrontement.20Geoffrey Omara, “UPDF Considers Withdrawing Forces from Lubero, Shifting Focus to North Kivu and Ituri,” Chimp Reports, 30 mars 2025 En plus du déploiement des UPDF, les autorités congolaises ont intensifié le recrutement et le soutien de groupes armés alliés pour appuyer les efforts de sécurité contre les ADF. Parmi ces acteurs figurent des milices locales d’autodéfense ainsi que les Wazalendo — une coalition peu structurée au départ composée de milices d’autodéfense formées par des jeunes, et dont les effectifs ont considérablement augmenté depuis la résurgence du M23.21UNSC, “Letter dated 27 December 2024 from the Group of Experts on the Democratic Republic of the Congo addressed to the President of the Security Council,” S/2024/969, Annex 10

Malgré le déploiement de troupes ougandaises supplémentaires et l’implication croissante de milices alliées, les ADF ont réussi à éviter les combats au cours du premier trimestre 2025. Entre janvier et mars 2025, ACLED ne recense que cinq affrontements impliquant les ADF, soit moins de 25 % de la moyenne trimestrielle d’affrontements impliquant le groupe enregistrés en 2024.

La pression militaire accrue exercée récemment par l’Ouganda sur les ADF s’inscrit dans le cadre de l’opération Shujaa, une opération multinationale de lutte contre le terrorisme menée conjointement par les forces ougandaises et congolaises depuis 2021. Dans le cadre de cette opération, les forces conjointes ont détruit de nombreux camps des ADF et contraint le groupe à se déplacer fréquemment pour éviter les affrontements avec les forces armées,22Africa Defence Forum, “Joint Military Operations Take Out Two Terror Figures in Eastern DRC,” 30 avril 2024 ce qui a limité sa capacité à établir des bases durables.23UNSC, “Letter dated 13 June 2023 from the Group of Experts on the Democratic Republic of the Congo addressed to the President of the Security Council,” S/2023/431,13 juin 2023 Si l’opération Shujaa s’est révélée efficace pour réduire le niveau global de violence des ADF, elle continue toutefois à rencontrer des difficultés pour endiguer les attaques contre les civils. Dans l’ensemble, les violences commises par les ADF ont atteint un pic en 2021, avant de diminuer chaque année depuis le lancement de l’opération Shujaa.

L’évolution de la structure des camps des ADF face à la pression militaire

Sous l’effet de la pression croissante exercée par l’opération Shujaa, les ADF ont été contraints d’adapter leur structure opérationnelle. Chaque camp fonctionne comme une unité à part entière, et toutes les opérations majeures doivent être notifiées à Baluku, chef suprême de l’organisation.24UNSC, “Letter dated 27 December 2024 from the Group of Experts on the Democratic Republic of the Congo addressed to the President of the Security Council,” S/2024/969, 27 décembre 2024, p. 7 Les camps des ADF sont composés à la fois de combattants, de leurs familles et de civils capturés, et utilisent fréquemment des structures mobiles, comme des tentes, pour se loger.25Andrew Bagala, “UPDF capture main ADF base,” Daily Monitor Uganda, 27 décembre 2021 Les ADF utilisent ces camps comme lieux d’habitation, de formation, de diffusion de l’idéologie de l’EI, de fabrication d’explosifs et de stockage d’armes.26Basaija Idd, “ADF Camp Capture, a Milestone Against Terrorism-UPDF,” Uganda Radio Network, 27 December 2021; Ryan O’Farrell, et al., “Clerics in the Congo: Understanding the Ideology of the Islamic State in Central Africa,” Hudson Institute, 11 avril 2024 Certains camps, comme l’ancien de Kambi Ya Yua, précédemment démantelé, s’étendent sur plus de trois hectares et comportent des structures semi-permanentes, notamment des clôtures et des baraques construites à partir de matériaux locaux.27Basaija Idd, “ADF Camp Capture, a Milestone Against Terrorism-UPDF,” Uganda Radio Network, 27 décembre 2021

Face aux opérations militaires conjointes menées depuis 2021, les ADF ont d’abord scindé leurs forces en au moins six camps, chacun dirigé par un commandant distinct, afin de permettre une mobilité accrue et de réduire les risques de détection.28UNSC, “Letter dated 27 December 2024 from the Group of Experts on the Democratic Republic of the Congo addressed to the President of the Security Council,” S/2024/969, 27 décembre 2024, pp. 6-7 Les camps des ADF ont utilisé diverses tactiques face aux autres groupes armés et à la population civile, changeant fréquemment leur localisation afin d’éviter les affrontements avec les forces armées congolaises et ougandaises.

À la mi-2024, les ADF ont consolidé leurs camps, passant de six à trois, et les ont déplacés vers des zones plus reculées, afin de pouvoir assurer une meilleure défense contre les forces congolaises et ougandaises (voir carte ci-dessous).29Kim Aine, “ADF Strikes Again in Eastern Congo, Civilians Bear the Brunt,” Chimp Reports, 17 janvier 2025; UNSC, “Letter dated 27 December 2024 from the Group of Experts on the Democratic Republic of the Congo addressed to the President of the Security Council,” S/2024/969, 27 décembre 2024, p. 7 En regroupant davantage de combattants dans un plus petit nombre de camps, les ADF ont cherché à renforcer leurs capacités défensives lors des affrontements avec les soldats congolais et ougandais.

Baluku commande le plus grand de ces camps, connu sous le nom de Madina, qui regroupe environ 1 000 personnes.30UNSC, “Letter dated 27 December 2024 from the Group of Experts on the Democratic Republic of the Congo addressed to the President of the Security Council,” S/2024/969, 27 décembre 2024, p. 7 Ce camp est situé à proximité de Lolwa, au nord de la rivière Ituri, dans le territoire de Mambasa.31Actualite, “DRC: ADF responsible for more than 650 deaths in Ituri and North Kivu since June,” 12 janvier 2025 Face à une pression militaire croissante en 2024, le camp de Madina s’est efforcé de se tenir éloigné des affrontements avec les forces armées congolaises et ougandaises en 2025 : entre janvier et mai, ACLED n’a recensé que trois événements violents en lien avec ce camp.

À la fin du premier trimestre 2025, l’offensive conjointe M23-RDF a atteint un camp des ADF situé dans le territoire de Lubero, dirigé par Ahmad Mahmood Hassan, plus connu sous le nom d’Abwakasi.32UNSC, “Ahmad Mahmood Hassan,” 21 avril 2025 Ce ressortissant tanzanien, qui apparaît fréquemment dans les médias des ADF, est réputé pour son expertise dans la fabrication d’explosifs, et aurait orchestré le massacre de 38 élèves en 2023 à l’école secondaire de Mpondwe-Lhubiriha, en Ouganda.33Jacob Zenn, “Abuwakas: The Arab–Tanzanian Face of Islamic State’s Jihad in the Congo,” Jamestown Foundation, 7 septembre 2023 Le camp sous le commandement d’Abwakasi était le plus meurtrier à l’égard des civils au cours de l’année passée. Les victimes civiles attribuées aux ADF dans le territoire de Lubero — la zone placée sous le commandement d’Abwakasi — représentent plus de 40 % du total des victimes civiles attribuées aux ADF depuis le milieu de l’année 2024.

Le troisième camp des ADF, dirigé par Seka Umaru, opère dans la région située au nord-ouest d’Oicha. Des experts de l’ONU présentent Seka Umaru comme le bras droit de Baluku et son successeur potentiel.34Actualite, “ADF still in control of Baluku, Daesh intensifies its demands in the DRC, according to the UN,” 12 janvier 2025 Umaru a rejoint les ADF après le départ de l’ancien chef Mukulu en 2014, et a été l’un des premiers membres à soutenir l’allégeance au commandement central de l’État islamique.35Ryan O’Farrell, et al., “Clerics in the Congo: Understanding the Ideology of the Islamic State in Central Africa,” Hudson Institute, 11 avril 2024

Les violences des ADF font de plus en plus de victimes civiles

Jusqu’à présent, en 2025, les ADF sont parvenus à éviter les confrontations directes avec les forces congolaises et ougandaises, ce qui s’est traduit par une diminution du nombre d’affrontements impliquant le groupe. Au moment où le M23 prenait le contrôle de vastes portions du Nord-Kivu et du Sud-Kivu au premier trimestre 2025, les ADF ont profité de la désorganisation des autorités et du désengagement de l’armée congolaise, alors focalisées sur la répression de la rébellion du M23, pour mener une série d’attaques meurtrières contre les civils. En conséquence, le nombre de victimes civiles a augmenté de 68 % par rapport au trimestre précédent, faisant du premier trimestre 2025 le deuxième trimestre le plus meurtrier en termes de violences contre les civils commises par les ADF depuis qu’ACLED a commencé à recueillir des données sur le groupe en 1997.

ACLED recense au moins 450 victimes civiles tuées par les ADF au cours du premier trimestre 2025, toutes non armées. Parmi ces victimes figurent 70 personnes enlevées puis exécutées en masse dans une église du territoire de Lubero, le 11 février. Cette attaque a fait suite à une série de raids simultanés sur cinq localités du territoire de Lubero le 15 janvier, ayant causé au moins 112 morts selon les estimations. Prise dans leur ensemble, ces attaques ont entraîné une augmentation de 15 % des incidents visant des civils au premier trimestre 2025 par rapport au dernier trimestre de 2024.

Les violences visant les civils commises par les ADF au premier trimestre 2025 ont augmenté non seulement en fréquence, mais également en létalité. À l’instar d’autres groupes affiliés à l’EI, les ADF ont tendance à mener chaque année un grand nombre d’attaques contre les civils, et constituent depuis 2018 l’acteur le plus violent à l’égard des populations civiles en RDC (voir graphique ci-dessous). Comparé aux autres groupes affiliés à l’EI, les ADF ont été, en 2024, le groupe le plus violent envers les civils. En effet, les attaques menées par le groupe ont fait de 2024 l’année la plus meurtrière en matière de violences contre les civils perpétrées par les ADF sous la direction de Baluku, avec plus de 1 600 victimes civiles signalées. Plutôt que de chercher à remplacer les autorités locales et à gouverner des zones de l’est de la RDC, les ADF ont plutôt tendance à ravager les territoires par des massacres de masse, des pillages à grande échelle, des enlèvements contre rançon et des incendies de biens.

Le groupe diffuse des photos et des vidéos de ces brutalités via ses propres canaux médiatiques et par l’intermédiaire du centre médiatique de l’EI.36UNSC, “Letter dated 27 December 2024 from the Group of Experts on the Democratic Republic of the Congo addressed to the President of the Security Council,” S/2024/969, 27 décembre 2024, Annex 9; exemple, voir X @WerbCharlie, 4 April 2025; X @War_Noir, 6 mars 2025 En échange de leur affiliation à l’EI et de la médiatisation des violences, souvent présentées sous l’angle d’un combat contre les « chrétiens », les « croisés » ou les « infidèles »,37UNSC, “Letter dated 27 December 2024 from the Group of Experts on the Democratic Republic of the Congo addressed to the President of the Security Council,” S/2024/969, 27 décembre 2024, Annex 9; exemple, voir X @WerbCharlie, 4 April 2025; X @War_Noir, 6 mars 2025 les ADF bénéficient de financements, de notoriété et de formations de l’EI, notamment via son réseau régional en Afrique orientale et australe, qui s’étend de la Somalie à l’Afrique du Sud.38Caleb Weiss, et al., “Rumble In The Jungle: ISCAP’s Rising Threat,” Hoover Institution, 6 juin 2023 Depuis le milieu de l’année 2024, le commandement central de l’EI publie de plus en plus de contenus médiatiques relatifs aux opérations des ADF, avec un délai de plus en plus court entre l’attaque et la mise en ligne des publications.

À mesure que la branche somalienne de l’EI s’affirme comme le centre névralgique des opérations globales du groupe,39Mustafa Hasan, “Somalia: The New Frontline in the Islamic State’s Global Expansion,” Washington Institute, 27 février 2025 les ADF semblent bénéficier de plus en plus de l’attention de l’EI à l’échelle du continent africain. Grâce au soutien financier et logistique fourni par le commandement central de l’EI, les ADF peuvent mener leurs opérations non pas en s’appuyant sur le soutien des populations locales, mais grâce à une légitimité externe obtenue auprès du commandement central de l’EI en s’adonnant à des violences brutales à l’encontre des civils.

Cette relation avec le commandement central de l’EI a également permis aux ADF d’accéder à des ressources et des formations pour fabriquer et utiliser des engins explosifs et, plus récemment, des drones. Chacun des camps des ADF dispose d’un nombre limité de drones, utilisés principalement à des fins de surveillance et pour éviter des confrontations directes.40UNSC, “Letter dated 27 December 2024 from the Group of Experts on the Democratic Republic of the Congo addressed to the President of the Security Council,” S/2024/969, 27 décembre 2024, Annex 5 Le 11 août 2024, les ADF ont tenté pour la première fois d’utiliser un engin explosif transporté par drone contre des soldats congolais à Malyajama, dans le territoire de Beni. Même si l’engin n’a pas explosé, cet incident montre la capacité croissante du groupe à recourir à ce type de technique à l’avenir.

Les ADF tirent parti de l’instabilité régionale

Pour combattre le M23, les FARDC devront probablement déployer plus d’hommes le long des lignes de front septentrionales, dans le territoire de Lubero. Ce redéploiement pourrait ouvrir de nouvelles zones d’opération aux ADF et à d’autres groupes armés, avec moins de résistance. Malgré les difficultés rencontrées par les FARDC, l’armée ougandaise s’est montrée ambitieuse en 2025 en accentuant la pression sur les ADF et d’autres groupes armés actifs en Ituri, notamment la CODECO.41David Ajuna and Felix Okello, “How top army commander died as UPDF killed 242 militants in DR Congo battle,” Monitor, 22 mars 2025

Le gouvernement ougandais redoute probablement que les ADF ne se rapprochent de la frontière ougandaise, à un moment où les FARDC sont mobilisées sur d’autres fronts ; une crainte fondée sur la propension des ADF à mener des attaques transfrontalières en territoire ougandais. Cependant, les UPDF à elles seules risquent de ne pas suffire à dissuader les ADF de commettre de nouvelles violences. Outre les UPDF, les FARDC devront probablement continuer de s’appuyer sur d’autres groupes armés locaux et des milices d’autodéfense pour contrôler certaines localités et se prémunir contre de futures attaques des ADF.

Si les armées ougandaise et congolaise ne parviennent pas à maintenir la pression actuelle sur les ADF, cela pourrait permettre au groupe de se réorganiser et d’adapter ses stratégies. Les tactiques de la terre brûlée utilisées fréquemment par les ADF pourraient alors évoluer vers des stratégies d’extraction des ressources plus stationnaires. Dès avril 2025, les ADF se sont engagés dans des activités génératrices de revenus qui laissent présager une volonté de contrôler certains territoires plus durablement, notamment à travers l’imposition de prétendues « taxes » sur les populations civiles et la prise de contrôle de sites miniers.42Radio Okapi, “Lubero: ADF accused of using Bapere populations for illegal gold mining,” 14 avril 2025; Radio Okapi, “ADF rebels impose taxes on Congolese farmers in Mutweyi,” 17 avril 2025 Ces formes d’exploitation économique locale sont peu courantes pour les ADF, qui, jusqu’ici, avaient davantage tendance à piller certaines zones puis à se retirer plutôt qu’à s’installer ou tisser des liens durables avec les populations civiles.

L’instabilité générée par la rébellion du M23, combinée aux opérations menées simultanément par les ADF dans le Nord-Kivu, a entraîné le déplacement de milliers de personnes et causé plus de 1 600 morts dans la province au cours des trois premiers mois de 2025.43Joshua Mutanava, “Lubero: In Biena, health facilities are struggling to function due to the activism of ADF rebels,” Actualite, 12 avril 2025 Dans les mois à venir, les accords de cessez-le-feu entre le Rwanda et la RDC ont peu de chances de réduire significativement les violences dans l’est du pays. Ils risquent plutôt de déplacer les dynamiques conflictuelles vers d’autres groupes armés, qui continueront à tirer parti de l’instabilité pour renforcer leur propre position dans la région. Le conflit avec le M23 a contraint les FARDC à détourner leur attention des ADF, ce qui pourrait permettre à ces derniers d’intensifier leurs attaques meurtrières contre les civils au cours du second semestre de 2025. Malgré une relative accalmie dans les avancées de la rébellion du M23, l’effondrement consécutif de l’autorité étatique a offert aux ADF de nombreuses opportunités pour renforcer leur présence dans l’est de la RDC, exposant ainsi davantage les populations civiles locales à des violences de masse.

Ce rapport a été écrit en anglais puis traduit en français. Les lecteurs doivent se référer au rapport en anglais en cas de divergence.

Visuals produced by Christian Jaffe.