Dear readers,

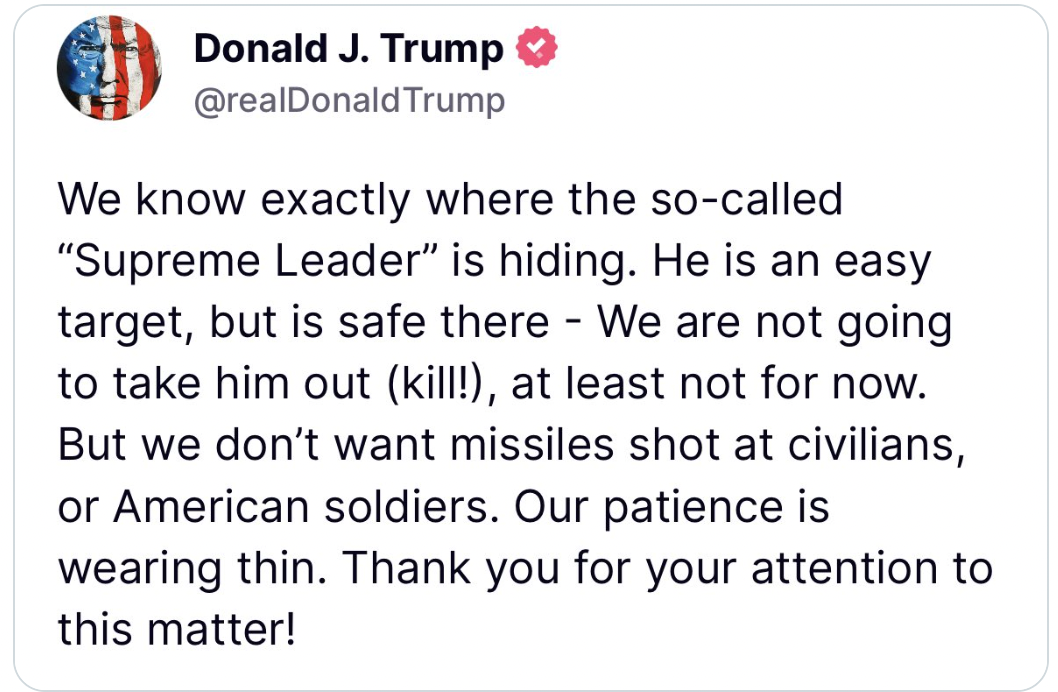

“Thank you for your attention to this matter!”

We are fast moving into a highly unstable future. I won’t use words like “unknown” because the turmoil that will affect many places could not be more obvious. As always, I will focus on the conflict and violence directions, with a detour into the (possible) near future, including setting the scene for the next 10 years in Iran, should the leader and leadership elite be eliminated.

Allow me to explain why: There is widespread consensus that the Iranian regime is dangerous internally and abroad. Israel’s actions to destabilize the regime are generally supported, but there is an impending sense of doom about what happens next. An Iran without nuclear and attack capabilities could result in an internally-directed “transition,” but such a scenario would be a facade for the country to create chaos in the region and remain a threat to Israel. A far more likely scenario is that Israel (with or without the United States’ support) decapitates the Iranian regime, but has a very poorly thought-out plan for what to do or how to placate the rest of the formidable power structure in the state. (I spoke with Nancy Ezzeddine at ACLED to get her excellent insights on this.)

Iran famously has multiple and repeated levels of military, intelligence, and security services, from the national to the local level. Such a system is vital for “coup-proofing” because the layers and redundancy limit the ability of any elite or group to covertly create a viable threat of sufficient size. By multiplying roles, there are many barriers to success (e.g., being caught and killed for subversion) before destabilizing someone at a scale of real authority. Military regimes typically have such structures despite their size and expense, high levels of internal competition, and high rates of public repression. They are very effective at securing institutional survival. The regime can constantly recreate and reconfigure itself in response to parts being removed or destabilized.

This means that killing Ayatollah Ali Khamenei and his surrounding elites does not destroy the regime, nor will it hasten the Iranian regime’s disintegration. It will trigger a continued conflict with internal and mainly external threats — Israel (and possibly the US) would need to attack the country, citizens, and resources until it creates a regime submission. And that is only the second step. (What is crazy to me is that the Israeli security forces know this! They seem to be so well prepared for the initial part, but leaving us in the dark as to everything else.)

The institutions of power, authority, and vast military abilities will still not “dissolve”; most will reconfigure themselves into an extremely able and agile opposition. They will undoubtedly fragment, with some defectors staying to support a transition. But former regime-based oppositions have massive advantages over a transitional authority, with their external ground troops necessary to secure and develop an internal power structure.

As to “who in the name of God is going to run the place after we decapitate a regime that no one wants?” I am writing this message in mid-June, after seeing the former Shah’s son, Reza Pahlavi, explain that he was going to descend upon Iran “as soon as possible,” amid continuing air attacks between Israel and Iran. This report claims — in no uncertain terms — that “Pahlavi lacks an organized following within the country … there is no serious monarchist movement in Iran itself.” This Pahlavi note is in a section about finding the right proxies post-regime removal, which, to my great dismay, doesn’t seem to have been an issue seriously thought about in 50 years. Other contenders included — shockingly — intellectuals (famous for their organizational abilities); student, labor, and civil society organizations (famous for agreement and compromise); and the “reformists” (famous for being the handmaidens of the regime). (The current President Masoud Pezeshkian may have some role in the (seemingly) impending future. Elected in 2024, a Council of Foreign Relations report damns him by faint praise, noting he “does not have such a sinister background, nor a close connection to Khamenei. He is a mild-mannered, middling parliamentarian whom regime officials allowed to run for office as a means of reengaging the public in the political process and improving the government’s public image.”) The report also notes my favorite line from recent reading: “One of the hardest tasks in fomenting a revolution, or even just unrest, is finding the right local partners.”

There will be no popular uprising to support US troops or an Israeli-favoured transitional leader. What is clear from all of this is that the devastating lessons from Afghanistan, Libya, Syria, and Iraq remain largely unlearned. Like Syria, an Iranian conflict could result in extreme levels of cruel violence. The domestic-violence abilities of its military and intelligence forces are not in question, and seemingly have no bounds. Like Libya, Iran has important economic resources that could sustain the fighting on both sides. Like Afghanistan, the militias that will come from the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps will have the Taliban’s advantage of home action, guaranteeing a long war. Like Iraq, an imposed order poorly challenged a roiling, bottomless cesspool of militias, where no remaining military or police force was left to ensure order. It could be an amalgamation of the worst-case scenarios that characterized the individual nightmares of these conflicts.

What is clear to me is that, like all revolutions, the positions that regimes and people have right now will radically change by the time this is over. This potential war will also change the calculus of power and violence in many other places. In our time of “peace through force,” current concerns — like Somalia — will struggle to make themselves relevant, and instead, neighboring powers will be expected to police and contain their areas. As a result, regionally and locally bound conflicts will spread like we have not seen. The geopolitical terrain is shifting — and not solely at the international level.

US protests

If that isn’t bad enough, let me just mention something about the US. As regular readers may know, there is both a sustained level of political violence in the US and a totally unsustained amount of talk about the level of political violence in the US. The killings of Minnesotan state representatives in June reawakened the public to the very real threat that continues to flare up in the US. We have covered the threat to local and state officials in our ongoing global series, noting that such attacks are pervasive and widespread.

In the US, it is an unavoidable temptation to equate these attacks with fascism, a decline in democracy, and partisan radicalization. But that would be a misreading of what is happening there at present. Every country has a signature to its political violence — for the US, it is “lone wolf” attacks on political figures, schools, and other areas where citizens are often vulnerable (street protests and car rammings have been popular in the past). These attack levels are constant rather than growing. However, despite being “political” against representatives and those in political positions, they are rarely, if ever, “partisan,” and so, they are distinct from the ongoing polarisation that plagues the US. This is a very dangerous phenomenon affecting both parties and their members.

The US does not have a democracy problem right now — it has a “law and order” problem. Who and what can evade the consequences of the legal system, who and what has a monopoly on violence (in a country of widespread firearm ownership and militarization), who and where are security forces focused on vs who and what is a public threat, are all questions that the US should be speaking about, rather than debating democratic backsliding. Through extremely hard work, the ACLED US team has collected the data from the recent surge in protests and analyzed the patterns here.

Notes and notions

The message to end all messages. Polite, but insane. No notes.

A few years ago, I had a cat named Ayatollah Katmeni, and she was wonderful. We didn’t refer to her as the “Supreme Leader,” but she was. ACLEDers had suggested her name in a contest which included “Hillary Kitten” and “Angela Meowkel.”

I like everything Helen Lewis writes.

In case one international crisis isn’t enough for you, remember May’s faceoff between India and Pakistan?

Frederick Forsyth died this month, having left us with incredible novels, including “The Day of the Jackal” (1971), which has been turned into a “good for a watch on a long flight” series. Some of my favourite books by him include “The Odessa File” (1972), “The Fourth Protocol” (1984), and “Icon” (1996).

I recently did this, and while the children look at it like some sort of poisonous plant, I have high hopes!

My Irish news right now is limited, but I return home next month and will provide too much in the next letter. I was going to mention Ballymena, but honestly, if you have gotten this far, I wish to spare you more horror.

Webinars

Gang violence in Ecuador: Navigating new ACLED data amid a wave of criminal activity

On 18 June, ACLED hosted a webinar to examine the findings of our latest analysis on gang violence in Ecuador by Senior Analyst for Latin America & the Caribbean, Tiziano Breda, and to do a deep dive into ACLED’s expanded coverage on gang-related violence across the country with Senior Methodology Officer, Rose Davies. The webinar also featured expert insights from the Director of the Ecuadorian Observatory of Organized Crime, Renato Rivera. You can view the webinar recording here.

ACLED in the media!

- Still on Ecuador, Ecuadorian news agencies Primicias and Telezmazonas highlighted findings from the report.

- An opinion piece written by Andrea Carboni, Giulia Bernardi, and Nicola Audibert on physical attacks on European politicians was featured in the EUobserver.

- Amid all the chaos unfolding in the US, Kieran Doyle was quoted in the New York Post, and Al Jazeera featured ACLED data on the demonstrations against Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

- ACLED data on the growing crisis in Gaza were featured in The Independent.

- Nichita Gurcov shared his insights on suspected Russian destabilization activities across Europe with Newsweek.

- ACLED data on expanding jihadist violence in West Africa was featured in articles by The New York Times and Deutsche Welle.

- Human Rights Watch cited ACLED data on the latest escalation of violence in South Darfur.

- The Washington Post used ACLED’s Conflict Index to analyze Trump’s travel ban.

- Le Monde drew from ACLED’s data in its article “What are the main armed conflicts in the world?”

- Last but not least, I was interviewed by Fox News about the conflict between Israel and Iran.