Q&A with

Pearl Pandya

South Asia Research Manager, ACLED

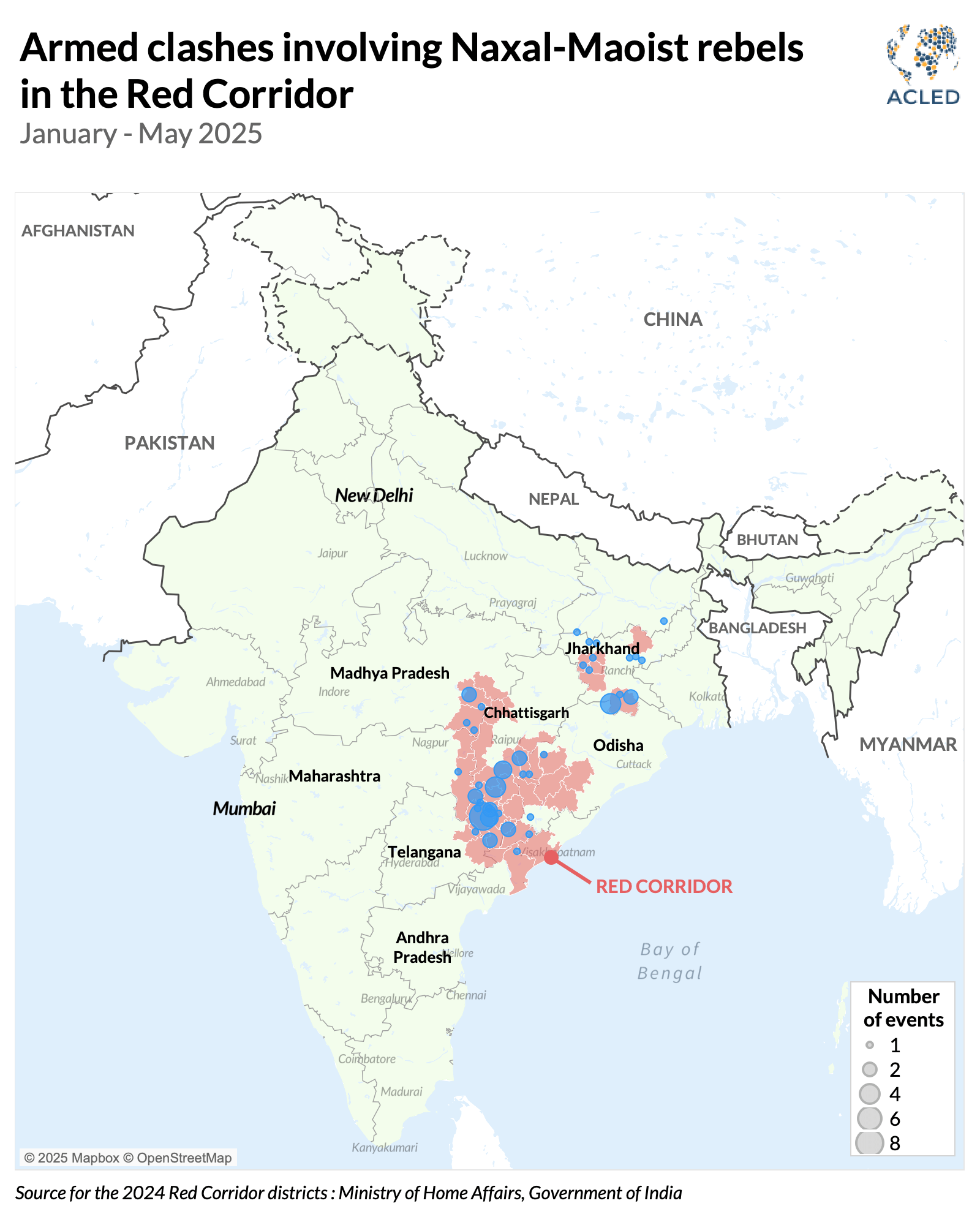

On 21 May, Indian security forces killed the general secretary of the Communist Party of India (Maoist) (CPI (Maoist)), Nambala Keshava Rao, also known as Basavaraju, in Chhattisgarh state. He was killed alongside 27 other cadres of the CPI (Maoist), the largest of the Maoist armed groups waging the Naxal-Maoist insurgency. Basavaraju’s death marks one of the most significant casualties in the Naxal-Maoist insurgency’s history, which first broke out in 1967 as a people’s war to secure the rights of socially disadvantaged groups — mainly landless laborers and tribal people. It is now concentrated in the tribal heartland of rural Central India, colloquially known as the Red Corridor.

In this Q&A, ACLED South Asia Research Manager Pearl Pandya discusses the Indian state’s recent successes and what they mean for the Naxal-Maoist insurgency, one of the longest-running insurgencies in the world.

The death of Basavaraju, the highest-ranking leader of the CPI (Maoist) to have ever been killed in combat, is obviously extremely significant. What sort of operations did we see from the Indian security forces leading up to it?

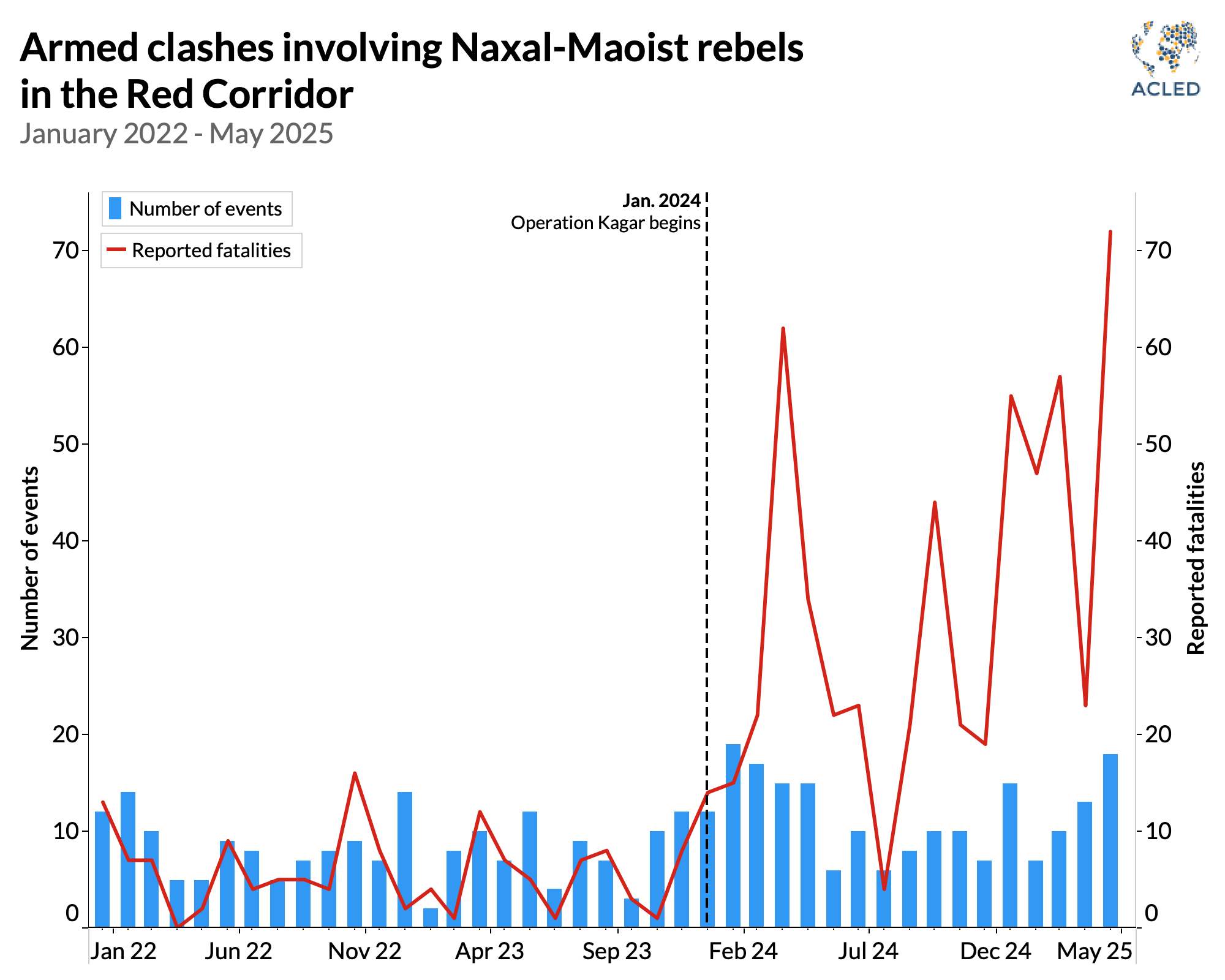

The Indian government held Basavaraju responsible for some of the insurgency’s deadliest attacks to date, including the 2010 Dantewada ambush, in which 76 paramilitary soldiers were reportedly killed.1Mayank Kumar, “Basavaraju—tech grad to Maoist commander-in-chief who scripted deadliest massacres including Dantewada,” The Print, 21 May 2025 So his killing certainly marks a major breakthrough, and it did not come out of the blue. Indian security forces have been increasing pressure on Naxal-Maoist rebels since the launch of Operation Kagar by the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)-led national government in January 2024 (see graph below). Security forces have engaged in more forward deployments involving coordinated action between central and state-level forces to pursue a stated aim of eradicating what the government calls “Left Wing Extremism” by March 2026.2Press Information Bureau, “Naxalmukt Bharat Abhiyan: From Red Zones to Growth Corridors,” Indian Ministry of Home Affairs, 10 April 2025 Greater cooperation between levels of government during this period has been supported by the BJP’s victory over the more progressive Indian National Congress in the December 2023 state elections for Chhattisgarh. Recent operations have spanned multiple days, as forces have encircled militants in forested areas and limited their escape routes. An increasing number of surrenders by Naxal-Maoist cadres has likely improved intelligence on militant whereabouts.3The Hindu, “Maoist surrenders double in first quarter; CRPF intelligence gets active,” 30 March 2025

Not only has the frequency of clashes between Indian security forces and Naxal-Maoist rebels increased, so, too, has the lethality of those clashes. In 2025, in particular, these clashes have become increasingly deadly. ACLED records at least 255 people killed so far in 2025 compared to 301 people in the whole of 2024. The rebels have made up the overwhelming majority of these fatalities. This suggests two things: the Naxal-Maoist cadres are likely weakened and unable to put up much of a resistance, but also that India might be going for an all-out military victory, preferring domination on the ground over arrests and surrenders.

How have the Naxal-Maoist rebels responded to this more aggressive approach, and what implications does it hold for the tribal communities who primarily inhabit these areas?

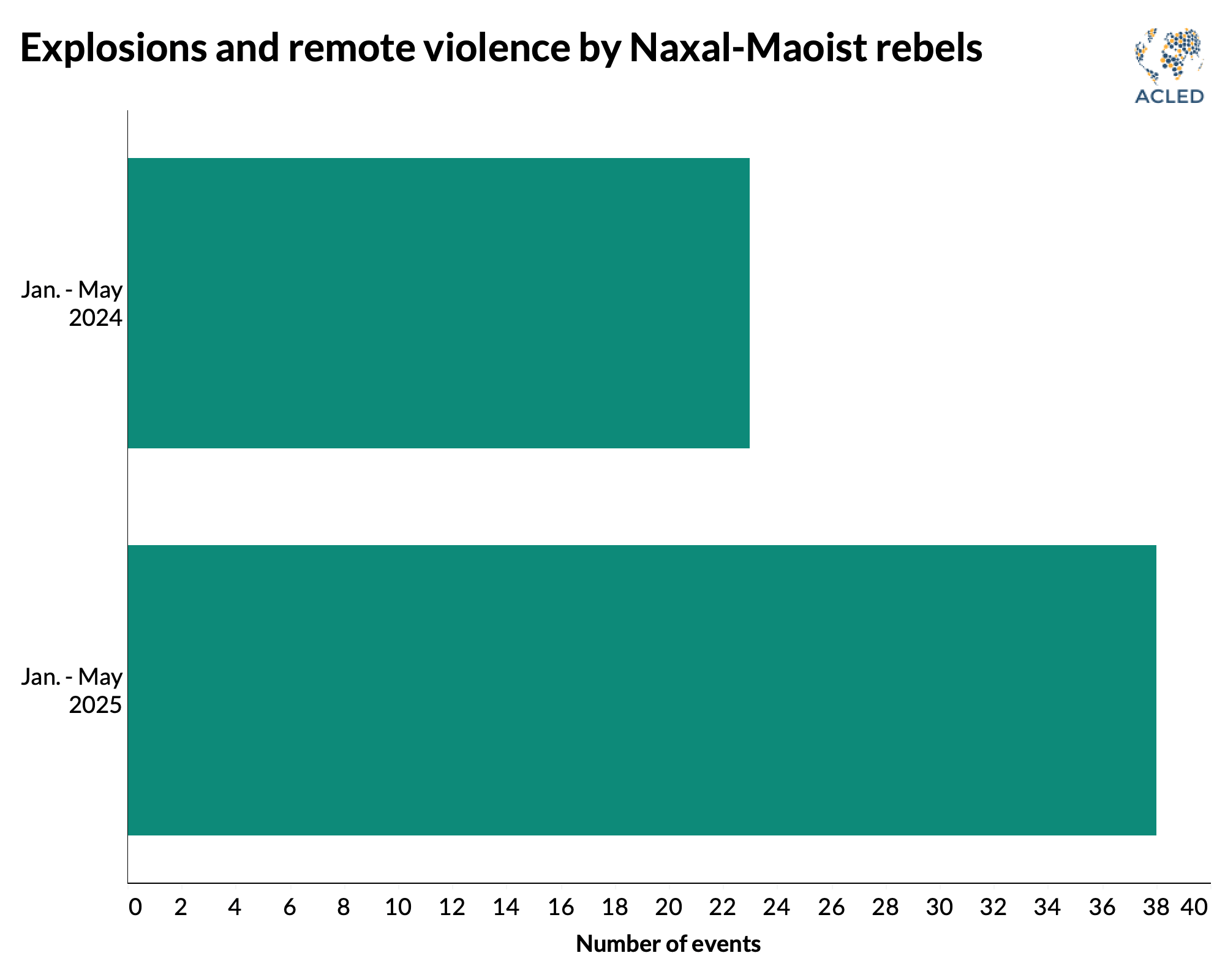

We have seen a shift in tactics to rely more heavily on remote violence. Our data show an increase in the use of explosive and remote violence by Naxal-Maoist rebels in 2025 compared to the same period last year (see graph below). This escalatory trend is likely to continue, as the rebels look to avoid direct engagement with security forces, who heavily outnumber them in concerted anti-militancy operations.

After successful anti-militancy operations, Naxal-Maoist rebels have also targeted locals whom they accuse of being police informants. In fact, reported civilian deaths from Naxal-Maoist violence increased by 27% in 2024, when the new approach got underway, compared to 2023. Although violence against civilians in 2025 so far has been slightly lower than the comparable period in 2024, the situation may worsen as the rebels come under increased pressure.

However, it’s important to mention that the locals, most of whom are indigenous Adivasi peoples, are not threatened only by the rebels. Human rights groups have expressed concerns over Indian security forces using indiscriminate force during their operations. They claim that civilians, including Adivasi villagers and unarmed cadres, have been killed alongside Naxal-Maoist rebels in some of the more lethal clashes.4Hannah Ellis-Petersen and Aakash Hassan, “Eradicating India’s jungle insurgency – can it be done and at what human cost?” The Guardian, 12 June 2025

What lies ahead for the insurgency?

We can expect a continued escalation in the use of force from the Indian government in line with its nationalistic narrative of being tough on extremists across the board, whether they’re militants in Kashmir or Naxal-Maoist cadres. Recent progress in road and communications connectivity in the Red Corridor, which is home to some of the most rural and isolated areas of India, also allows security forces to go deeper into what were previously rebel sanctuaries.

As for the Naxal-Maoist rebels, they are indisputably a militarily weaker force than before. Besides the high number of casualties, both of foot soldiers and senior CPI (Maoist) leaders, their geographic presence has also shrunk.5Press Information Bureau, “Achieving a historic success in the resolve of a ‘Naxal-free India’, security forces kill 31 Naxalites in the biggest-ever operation against Naxalism at Karreguttalu Hill (KGH) on Chhattisgarh-Telangana border,” Indian Ministry of Home Affairs, 14 May 2025 And they are aware of this: The CPI (Maoist) has made overtures since March for conditional peace talks, though the central government is yet to formally respond.

Having said that, the ideological underpinnings of the insurgency, particularly social justice and land rights for disadvantaged groups, still resonate deeply among the local Adivasi population. The Red Corridor, which contains some of the most mineral-rich areas in the country, has emerged as a flashpoint between politicians, who prefer industrialization, and the locals, who fear the loss of their ancestral lands and subsequent displacement. Naxal-Maoist rebels could continue to find recruitment opportunities in this situation. At the same time, this contestation may also serve as a ready cause célèbre, facilitating their transition into a political movement should they choose to do so.

Visuals produced by Ana Marco.