6 May 2025 – The Oval Office is packed, cameras flashing as United States President Donald Trump fields questions beside Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney. Mid-sentence, Trump drops the news: “The Houthis have announced they don’t want to fight anymore … we will stop the bombings … they have capitulated.”1Ryan King and Ronny Reyes, “Trump says US ‘will stop’ bombing Yemen’s Houthis, claims ‘they don’t want to fight anymore,’” New York Post, 6 May 2025 The terms of the deal emerge a few hours later — not from Washington, but from Muscat. The Sultanate of Oman, the quiet broker, breaks the silence: “neither side will target the other, including American vessels, in the Red Sea and the Bab al-Mandab Strait.”2Peter Eavis, “Red Sea Passage Remains a No-Go for Shipping Despite U.S. Action,” The New York Times, 5 June 2025

Meanwhile, the Houthis deliver a defiant addendum: They will continue their attacks on Israel.3The Times of Israel, “Houthis declare attacks on Israel to continue after ceasefire reached with US,” 6 May 2025 On 8 May, Abdulmalik al-Houthi, leader of the Houthi movement, addresses the nation. He reaffirms support for Gaza and dismisses the ceasefire as a side note. “The American announcement,” he says, “is not the result of surrender … this is the clowning that Trump is known for.”4War Media, “Speech of Sayyid Abdul-Malik Badr al-Din al-Houthi on the latest developments in the Israeli aggression on Gaza and the latest regional and international developments – 10 Dhu al-Qi’dah 1446 AH, 8 May 2025 AD,” 8 May 2025 (Arabic)

This exchange presents the established fact of the US-Houthi ceasefire — though not without some political theater. Each side pushed its own version of the story, highlighting the contradictions that have shaped the Red Sea crisis from the outset. The US and its allies leaned hard on talk of “freedom of navigation.” The Houthis, by contrast, framed their actions as resistance to Israeli aggression on Gaza. But in this hall of mirrors, public statements obscured more pragmatic interests, and the conflict followed a logic driven less by principles than by strategic considerations.

Houthi operations in the Red Sea and against Israel began on 19 October 2023 and have continued to the present day (see map below). Though often portrayed as a single crisis, the Red Sea conflict actually involves three distinct fronts: Houthis vs. Israel, Houthis vs. commercial shipping, and Houthis vs. the US. Over the past year and a half, the group has launched more than 520 attacks — targeting at least 176 ships and carrying out 155 strikes on Israeli territory. The US has responded with a two-pronged approach: an international maritime defense initiative, Operation Prosperity Guardian, and two air campaigns, Operation Poseidon Archer and Operation Rough Rider, aimed at degrading Houthi military capabilities. Together, these operations have resulted in 774 airstrike events and at least 550 victims between 12 January 2024 and 6 May 2025.

Contrasting rhetoric and facts reveals the concealed agendas of both the US and the Houthis. US air attacks in Yemen have not fully degraded the Houthis’ long-range drone and missile arsenal. And, in the logic of asymmetric warfare, the Houthis do not need many weapons — just a few well-placed “golden shots,” or high-impact strikes, can still shake up global shipping and trigger a new regional crisis. In the end, the real strength of Houthi deterrence is not the scale of their arsenal, but their ability to sustain a heightened perception of risk. It is clear that — despite public declarations — the Red Sea standoff is far from over.

What the Houthis say they are doing

The Houthis’ “phased escalation”: action or rhetoric?

“The longer the Israeli enemy continues and escalates on the Palestinian people in Gaza and the longer the aggression lasts, we will head to new stages.”

Abdulmalik al-Houthi, leader of the Houthi movement, 21 July 20245Humanitarian Operations Coordination Center, “Revolution leader: Targeting occupied ‘Jaffa’ marks beginning of fifth phase of escalation,” 21 July 2024

A key element of the Houthis’ rhetoric is to portray their military actions in support of Palestine as increasingly gradual, what they call a “phased escalation.” Using rhetoric to signal progressive intensification of military operations, the Houthis aim to exploit uncertainty surrounding their actual military capability to compel Israel and their allies to halt their operations in Gaza. Yet, are these rhetorical escalations matched by concrete operational shifts?

Between November 2023 and July 2024, the Houthis announced five phases of escalation (see graphs below). The first three phases reflected a genuine broadening of both targets and geography — from Israeli-linked vessels, to all ships bound for Israel, and eventually to American and British interests. These phases were marked by concrete actions, including a high-profile hijacking, the first sinking of a commercial vessel, the deployment of new weapons such as underwater drones, and a direct military confrontation with Western forces.

However, after Phase 3, the escalation pattern began to break down. Phases 4 and 5 were largely rhetorical, with little operational follow-through. Phase 4 promised expansion into the Mediterranean,6Middle East Monitor, “Houthis announce fourth escalation phase, sanctions on all ships associated with Israel’s ports if Rafah invaded,” 4 May 2024. This announcement was preceded by the 14 March declaration to block Israel-linked ships in the Indian Ocean which resulted in only one corroborated attack by the end of April 2024. but resulted in no confirmed attacks. Similarly, Phase 5 was launched following a successful Houthi drone strike in Israel,7Humanitarian Operations Coordination Center, “Revolution leader: Targeting occupied ‘Jaffa’ marks beginning of fifth phase of escalation,” 21 July 2024 but did not result in a strategic expansion. Rather, it led to a shift in focus away from Red Sea shipping toward targeting US warships and Israeli territory. Ultimately, these later phases functioned as symbolic announcements aimed at maintaining a heightened sense of risk around Houthi operations, while signaling continued commitment to the Palestinian cause.

As seen in previous drone and missile campaigns, Houthi rhetoric leverages uncertainty about their actual capabilities to signal ongoing escalation and cultivate deterrence, even in the absence of concrete operational shifts.

Gaza’s southern front: Houthi attacks on Israel

“The air raid sirens sound … and they flee from their beds towards shelters. Some of them die while they rush towards shelters in the escape operations. This state of terror, fear, and anxiety has its importance.”

Abdulmalik al-Houthi, 16 January 20258War Media, “Speech of Sayyid Abdul-Malik Badr al-Din al-Houthi on the announcement of the ceasefire agreement in Gaza and the latest regional and international developments – Rajab 16, 1446 AH | January 16, 2025 AD,” 16 January 2025 (Arabic)

Houthi military involvement in the Gaza crisis began on 19 October 2023 after the al-Ahli hospital incident, which they considered a “red line” crossed by Israel.9War Media, “Speech of Sayyid Abdul-Malik Badr al-Din al-Houthi on the latest developments in the Palestinian arena, 25 Rabi’ al-Awwal 1445 AH,” 10 October 2023 (Arabic) In these early phases of the conflict, the Iranian-led “axis of resistance” sought to avoid regional escalation, and both Iran and Hezbollah indicated that retaliation against Israel would come from Yemen and Iraq.10Hanin Ghaddar, “What Did Nasrallah Really Say, and Why?,” The Washington Institute, 3 November 2023 In line with this posture, the Houthis launched a campaign of drone and missile strikes targeting southern Israel, framed as “deterrent action” vis-à-vis Tel Aviv.11X @abdusalamsalah, 17 October 2023 Operationally, they claimed that their attacks disrupted activity at “targeted bases and airports”12X @Yahya_Saree, 7 November 2023 inside Israel.

Despite their claims, initial Houthi strikes on Israel appeared more symbolic than strategic.13Amwaj, “Deep Dive: Houthis effectively declare war on Israel after drone, missile barrage,” 31 October 2023 These were likely intended as a show of solidarity with Gaza and a sign of escalatory posture, rather than a campaign expected to achieve significant military outcomes. Most attacks were intercepted, with only minor damage reported, primarily from debris falling on Israeli territory. Still, it is worth more closely scrutinizing whether the attacks disrupted flight operations in Israel as much as the Houthis claim.

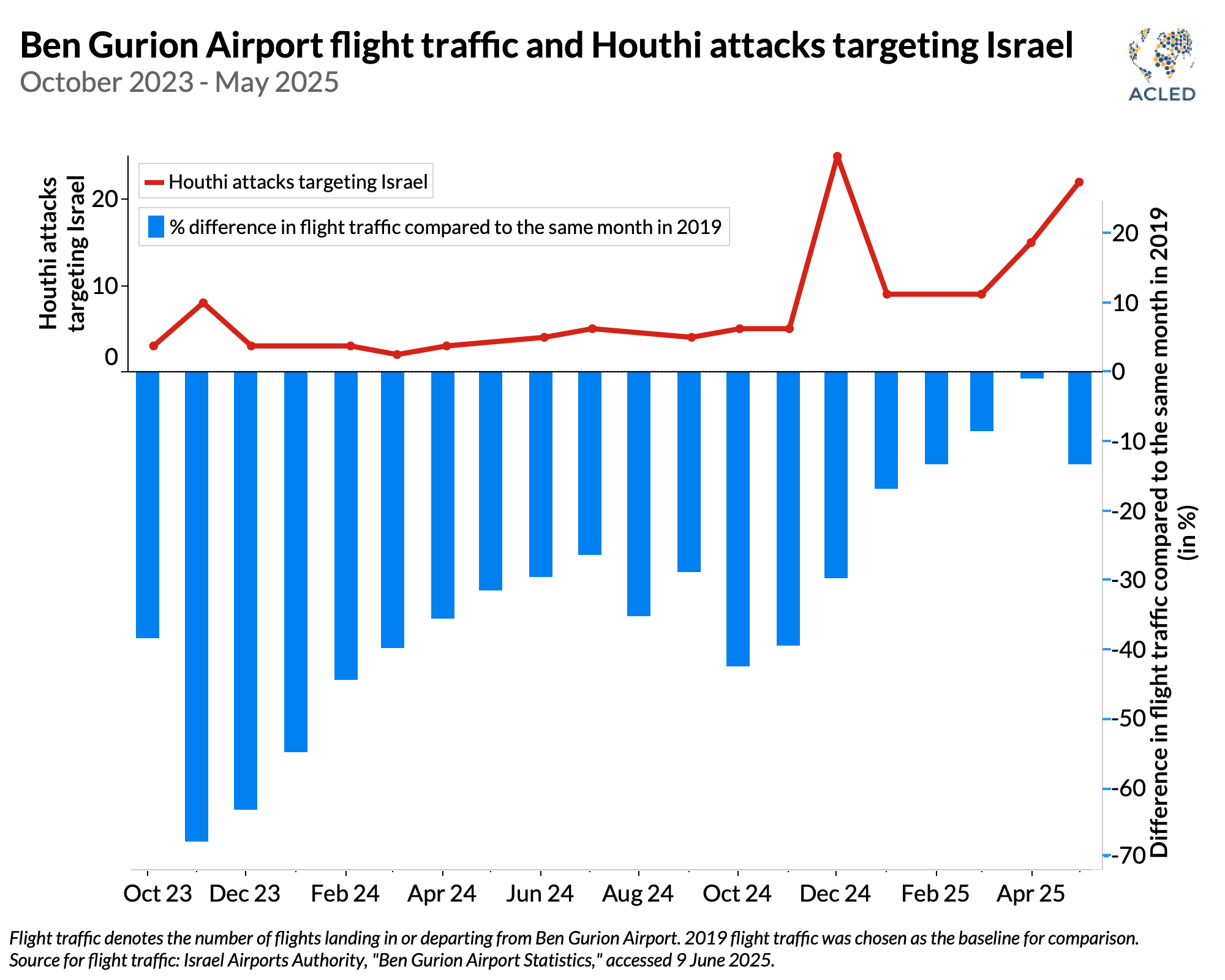

Mass cancellation of flights in Israel started around 10 October 2023,14Al Jazeera, “Major international airlines suspend flights to Israel amid war on Gaza,” 10 October 2023 before the Houthi attacks. The cancellations were prompted by the immediate security fallout that ensued from the Hamas-Israel war. For instance, although Ben Gurion International Airport is located in central Israel and was unaffected by the strikes, flight traffic there dropped by around 30% in October 2023 compared to the same month the year before. The heightened perception of risk caused a long-term drop in the number of flights that lasted a full year, until October 2024. Though the Houthis were not directly responsible for these disruptions, they exploited the crisis to claim symbolic credit through sporadic, low-intensity attacks.

This strategy evolved in July 2024, when Abdulmalik al-Houthi announced Phase 5 of Houthi attacks, signaling a shift toward more impactful attacks against Israel.15Humanitarian Operations Coordination Center, “Revolution leader: Targeting occupied ‘Jaffa’ marks beginning of fifth phase of escalation,” 21 July 2024 The announcement followed the successful penetration of Israeli defenses by a Houthi drone dubbed “Yaffa”16Yaffa is also the Arabic word used to identify Tel Aviv. that, for the first time, struck Tel Aviv, killing one civilian and injuring several others. The new drone signaled the acquisition of unprecedented long-range capabilities.17X @manniefabian, 21 July 2024 The attacks in September confirmed this trajectory, when the group used the Palestine-2 “hypersonic” missile18In all likelihood, the Palestine-2 missile is a variant of the Iranian Fattah-1 solid propellant ballistic missile not capable of reaching hypersonic speed. It was previously deployed by the Houtis to target Eilat on 3 June 2024 under the name “Hatim,” reflecting a typical rebranding strategy aimed at showcasing supposed technological advancement. See: X @fab_hinz, 5 June 2024; Emily Milliken, “Do the Houthis really have a hypersonic missile?” Atlantic Council, 24 September 2024 to strike the Israeli cities of Ashkelon and Haifa, demonstrating another significant technological leap.

In this new phase, Abdulmalik al-Houthi provided a clear summary of the objectives behind his group’s attacks on Israel by outlining two main goals: disrupting flight routes through Ben Gurion Airport and creating a “state of terror, fear, and anxiety” in Israel.19War Media, “Speech of Sayyid Abdul-Malik Badr al-Din al-Houthi on the announcement of the ceasefire agreement in Gaza and the latest regional and international developments – Rajab 16, 1446 AH | January 16, 2025 AD,” 16 January 2025 (Arabic) Indeed, the group refocused its attacks on Israel from September 2024, culminating in a major escalation between December 2024 and January 2025 when it deployed nearly daily attacks.

However, it appears that increased Houthi attacks and the shift in focus toward Ben Gurion Airport did not achieve their intended effect. Rather than triggering a sustained decline, flight numbers began recovering from December 2024 onward, despite increasing Houthi strikes (see graph below). This trend suggests that, despite the increasing frequency of Houthi strikes, their limited effectiveness enabled Israel’s aviation sector to gradually recover, even if flight volumes remained below pre-crisis levels.

On 4 May 2025, the Houthis declared a “comprehensive aerial blockade”20Middle East Monitor, “Yemen’s Houthis threaten ‘comprehensive aerial blockade’ on Israel,” 5 May 2025 on Israel and, on the same day, successfully struck Ben Gurion Airport, causing material damage and injuring four civilians. Although airline companies had largely ignored the increased frequency of Houthi attacks since March, the symbolic impact of this direct hit prompted several carriers to suspend all flights to Israel.21Middle East Monitor, “Airlines halt all flights to Israel after Houthi missile lands near airport,” 5 May 2025 As a result, air traffic at Ben Gurion Airport dropped by 13% compared to the same month in 2019 (see graph above), the last year before the Covid-19 pandemic, thus reverting the upwards trend observed since December 2024.

This last case proves an important point: An escalation in the frequency of attacks does not necessarily increase risk perception if those attacks are unsuccessful. However, “golden shots” can have a disproportionately large effect and trigger a prolonged crisis dynamic that may persist for months. This is a hallmark strategy that shows how the Houthis navigate the asymmetrical warfare they face.

Weaponizing the waterways: Houthi strategy in the Red Sea

“In the Red Sea, especially in Bab al-Mandab and what borders Yemeni territorial waters, our eyes are open for constant monitoring and searching for any Israeli ship.”

Abdulmalik al-Houthi, 14 November 202322War Media, “Speech of Sayyid Abdul-Malik Badr al-Din al-Houthi on the anniversary of the martyrdom and the latest developments 04-30-1445 AH 11-14-2023 AD,” 14 November 2023 (Arabic)

The expansion of Houthi attacks on commercial shipping was announced on 14 November 2023,23X @Yahya_Saree, 14 November 2023. This initial geographical delimitation was clearly overstated, as the Houthis went on to announce geographical expansions of their operations in subsequent phases. aligning with Iranian Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khamenei’s call earlier that month for an embargo on Israel.24The New Arab, “Iran’s Khamenei calls for Arab-Islamic boycott, oil embargo on Israel over Gaza,” 1 November 2023 It began with the hijacking of the Galaxy Leader on 19 November 2023 — an operation that reverberated globally — and continued with attacks on seven additional vessels. The Houthis typically frame these attacks, along with strikes on Israel, as acts of solidarity with Gaza and direct responses to Israeli military operations. Based on this rationale, the Houthi leadership has linked their operations to the course of the Gaza war — notably halting all attacks following the 19 January 2025 Israel-Hamas ceasefire.

This latter correlation is often misinterpreted as evidence that Houthi attacks in the Red Sea are a direct response to developments in Gaza. In reality, this is not the case for at least two reasons. First, irrespective of the situation in Gaza, the Houthis have leveraged these attacks to advance their own domestic and regional agendas. Second, despite their public rhetoric, they have shown little willingness to pursue operations that would harm their strategic interests.

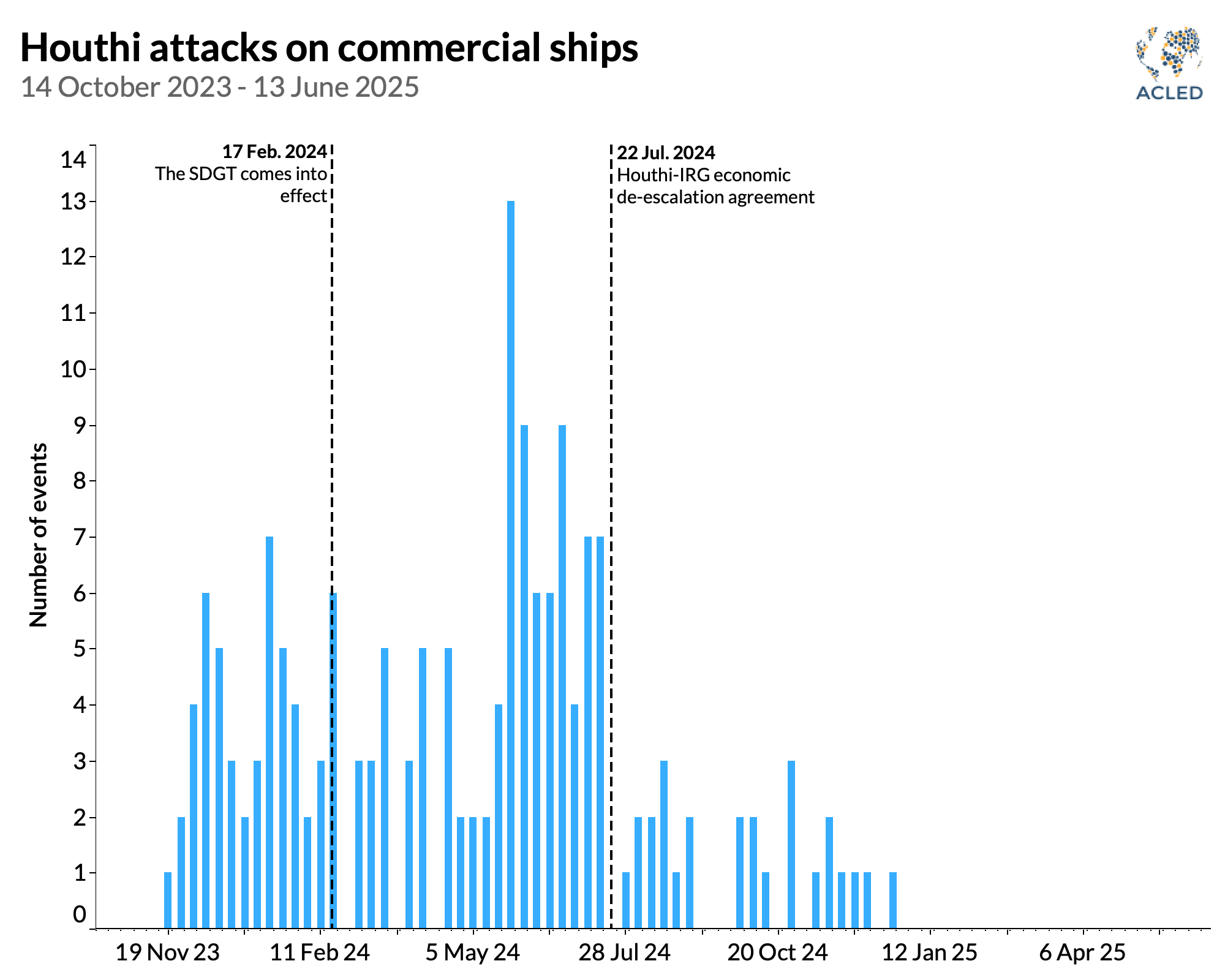

ACLED data show that major Houthi attack patterns unfolded independently of Gaza. For instance, the February 2024 spike in Houthi attacks in the Red Sea — the highest weekly number up to that point — followed the Houthis’ designation as a Specially Designated Global Terrorist (SDGT) group by the US.25The New York Times, “U.S. Designates Houthis a Terrorist Group,” 16 January 2024 Similarly, in late May 2024, the Houthis escalated their attacks after Yemen’s Internationally Recognized Government (IRG) introduced measures to assert control over the financial sector and weaken the Houthis’ economic power.26Al-Sharq Al-Awsat, “The Central Bank of Yemen strengthens its control over foreign transfers,” 28 May 2024 (Arabic); X @Alsakaniali, 30 May 2025 Almost concurrently, the US sharply escalated its airstrikes on Houthi critical infrastructure, ending a five-week pause.

This combined pressure prompted an unprecedented Houthi response. The last week of May 2024 saw the highest number of attacks on commercial shipping recorded in a single week, followed by record-breaking monthly surges in June and July. In an unprecedented move, the Houthis also sank the Greek-owned, Liberia-registered Tutor Bulk Carrier using a new drone boat dubbed “Tufan.” Critically, the attacks completely ceased by the time an agreement brokered by Saudi Arabia — the economic de-escalation accord27Office of the Special Envoy of the Secretary-General for Yemen, “Briefing by the UN Special Envoy for Yemen, Hans Grundberg, to the Security Council, 23 July 2024,” 23 July 2024 — prompted the IRG to lift the financial restrictions on the Houthis.

A second key point is that the Houthis have deliberately scaled back attacks on commercial shipping based on their political calculations and despite the continuous escalation in Gaza. After the July 2024 economic de-escalation accord, maritime attacks paused for two weeks as talks with Saudi Arabia progressed toward a United Nations peace roadmap. Attacks on commercial vessels declined sharply from September and ceased entirely by December 2024 (see graph below), even as operations against US and Israeli targets widened. An exception to this de-escalation pattern was the strike on the Greece-registered oil tanker MV Sounion in August, which, according to a security expert interviewed by the author, was orchestrated by hardline Houthi factions operating independently of the Houthi negotiating team, with the aim of disrupting talks with Saudi Arabia.28Personal communications with an Omani security expert in Muscat, ACLED, May 2025

The Houthis have never publicly acknowledged halting their attacks on commercial shipping, and this shift likely reflects multiple strategic calculations. First, months of sustained attacks and US strikes likely degraded part of the Houthi arsenal,29Edward Beales and Wolf-Christian Paes, “Operation Poseidon Archer: Assessing one year of strikes on Houthi targets,” IISS, 18 March 2025 prompting the group to conserve drones and missiles so it can replenish its stockpile and sustain operations over the long term.

Second, the Houthis have long relied on a strategy of marginal gains, using largely symbolic strikes to amplify risk perception. In this sense, a limited number of attacks can yield significant psychological and strategic effects without depleting resources.

Finally, the halt in commercial shipping targeting may reflect a deliberate effort to decouple the Red Sea attacks from the Palestinian cause. By easing pressure on maritime trade, the Houthis likely aimed to reduce international backlash while continuing to support the Palestinian cause through more targeted military activity.

Notably, this shift aligns with recent developments. The Houthis announced the resumption of attacks on Israeli commercial vessels on two separate occasions: first on 11 March 2025, when they reinstated a “ban on the passage of all Israeli ships” in the Red Sea,30Hod Hod Yemen News, “Yemen enforces naval blockade on ‘Israel’ after four-day ultimatum ends,” 11 March 2025 and again on 20 May 2025, when they declared “a comprehensive ban on maritime navigation to and from the Port of Haifa.”31Humanitarian Operations Coordination Center, “Press Release No. (005) – 19 May 2025,” 19 May 2025 However, they did not follow through on these attacks.

Lastly, the Houthis have also indirectly exploited the Red Sea crisis domestically. The Palestinian cause enjoys widespread popularity in Yemen: Since October 2023, the number of Houthi-sponsored, pro-Palestine demonstrations has exceeded by more than double all other recorded demonstrations in Yemen since ACLED data collection began in 2015. Furthermore, the crisis has boosted recruitment, with Houthi fighters now estimated at around 350,000. Concurrently, US and Israeli airstrikes have given the Houthis a pretext to intensify repression and silence dissent at home.

What others say the Houthis are doing

“No terrorist force will stop American commercial and naval vessels from freely sailing the Waterways of the World.”

US President Donald Trump, 15 March 202532The White House, “President Trump Is Standing Up to Terrorism and Protecting International Commerce,” 15 March 2025

While the Houthis assert that their attacks are limited to Israel, the US, and the United Kingdom, international stakeholders have primarily raised concerns about the broader implications for freedom of navigation and the security of global trade routes. Announcing the launch of Prosperity Guardian, former US Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin warned that Houthi attacks “threaten the free flow of commerce, endanger innocent mariners, and violate international law,”33The White House, “Statement from Secretary of Defense Lloyd J. Austin III on Ensuring Freedom of Navigation in the Red Sea,” 18 December 2023 urging global support for freedom of navigation.34The UN Security Council, in resolution 2722, condemned attacks that “impede global commerce and undermine navigational rights.” Similarly, the European Union’s Aspides mission aimed “to restore and safeguard freedom of navigation, for the sake of the EU, the region, and the wider international community.” See: UN Security Council, “Resolution 2722 (2024) / adopted by the Security Council at its 9527th meeting, on 10 January 2024,” 10 January 2024; European External Action Service, “EUNAVFOR Operation Aspides,” April 2025

The Houthis consistently rejected accusations that they were threatening maritime security and instead advanced a counter-narrative that blamed the US and its allies for militarizing the Red Sea and triggering the crisis. This is a claim they’ve made since April 2022, when the US established Combined Task Force 153 to patrol the waterway.35Megan Eckstein, “Combined Maritime Forces establishes new naval group to patrol Red Sea region,” Military Times, 13 April 2022. In response to the announcement, Muhammad Ali al-Houthi launched the hashtag “The navy has its men” to reiterate Houthi preparedness to attack any target using drones and missiles, even at sea. This rhetoric intensified with the launch of OPG and OPA. See: The Jerusalem Post, “Houthis vow to keep up Red Sea attacks after US-led strikes,” 15 January 2025 The Houthis maintained that their attacks posed no threat to freedom of navigation and claimed that “all commercial ships in the Red and Arabian Seas are safe, with the exception of Israeli ships or those heading to Israel, only and only.”36Aziz El Yaakoubi, “Houthis vow to keep up Red Sea attacks after US-led strikes,” Reuters, 16 January 2024 But does this claim hold up?

Are the Houthis only targeting US, UK, and Israeli ships?

“A simple step to protect yourself from American and British extortion through maritime insurance costs … is to publicly declare: ‘We have no connection with Israel’ for every ship crossing the Red Sea, Bab al-Mandab, or the Arabian Sea.”

Muhammad Ali al-Houthi, member of the Supreme Political Council, 7 January 202437X_@Moh_Alhouthi, 7 January 2024

During the Red Sea crisis, some commercial ships sent messages through their broadcast and identification systems like “not headed to Israel.” This was following advice by Houthi leaders to avoid potential targeting.38Tomer Raanan, “Houthi leader tells ships to deny Israel links on AIS,” Lloyd’s List, 8 January 2024 Others tried to conceal their position and destination by turning off their broadcast system. However, on several occasions, Houthi targeting was inaccurate and unrelated to destination or nationality.39Noam Raydan, “Houthi Ship Attacks Are Affecting Red Sea Trade Routes,” The Washington Institute, 7 December 2023

ACLED data indicate that Houthi attacks targeted commercial vessels linked to over 50 nationalities. Yet, only 17% of these ships had publicly known affiliations with Israel, the US, or the UK. The most frequently targeted were Greek-linked vessels (27%), followed by those registered under Liberia (8%), Cyprus (7%), and Panama (5%). Indeed, the Houthis applied a loose filter in determining affiliation with Israel, targeting companies such as the Swiss-Italian Mediterranean Shipping Company (MSC), whose ownership has familial connections to the country.40MSC is owned by the Aponte family: Italian businessman Gianluigi Aponte and his wife, Rafaela Aponte-Diamant, who was born in Haifa, Israel. Overall, these broad criteria reinforced the perception that commercial shipping was being targeted indiscriminately, contradicting Houthi claims that “all commercial ships are safe.”

Who caused the crisis? The Houthis’ narrative on trade

“We reiterate our confirmation that the [Houthis’] target is Israeli ships or those heading to the ports of occupied Palestine.”

Muhammad Abdussalam, head of the Houthi National Delegation, 22 January 202441Aziz Hamdi, “US exploits events in Red Sea to fabricate international crisis: Houthis,” Anadolu Agency, 22 January 2024

As part of their anti-US rhetoric, the Houthis also claimed that their attacks did not disrupt global trade flows, but rather that the US fabricated the crisis by pressuring shipping companies to reroute or halt operations.42Al-Mayadeen English, “Yemen reiterates shipping safety in Red Sea amid US propaganda,” 16 January 2024 Indeed, many companies stopped using these waterways due to higher premiums required for “war risk” insurance that protects their ships from losses related to conflict. However, this enormous increase in war risk premiums was triggered by the Houthis’ attacks. This effectively reduces the group’s narrative down to a deflection tactic that blames the financial system for rationally responding to the risks they created. Nonetheless, the Houthis masterfully exploited this system to maximize the effectiveness of their attacks.

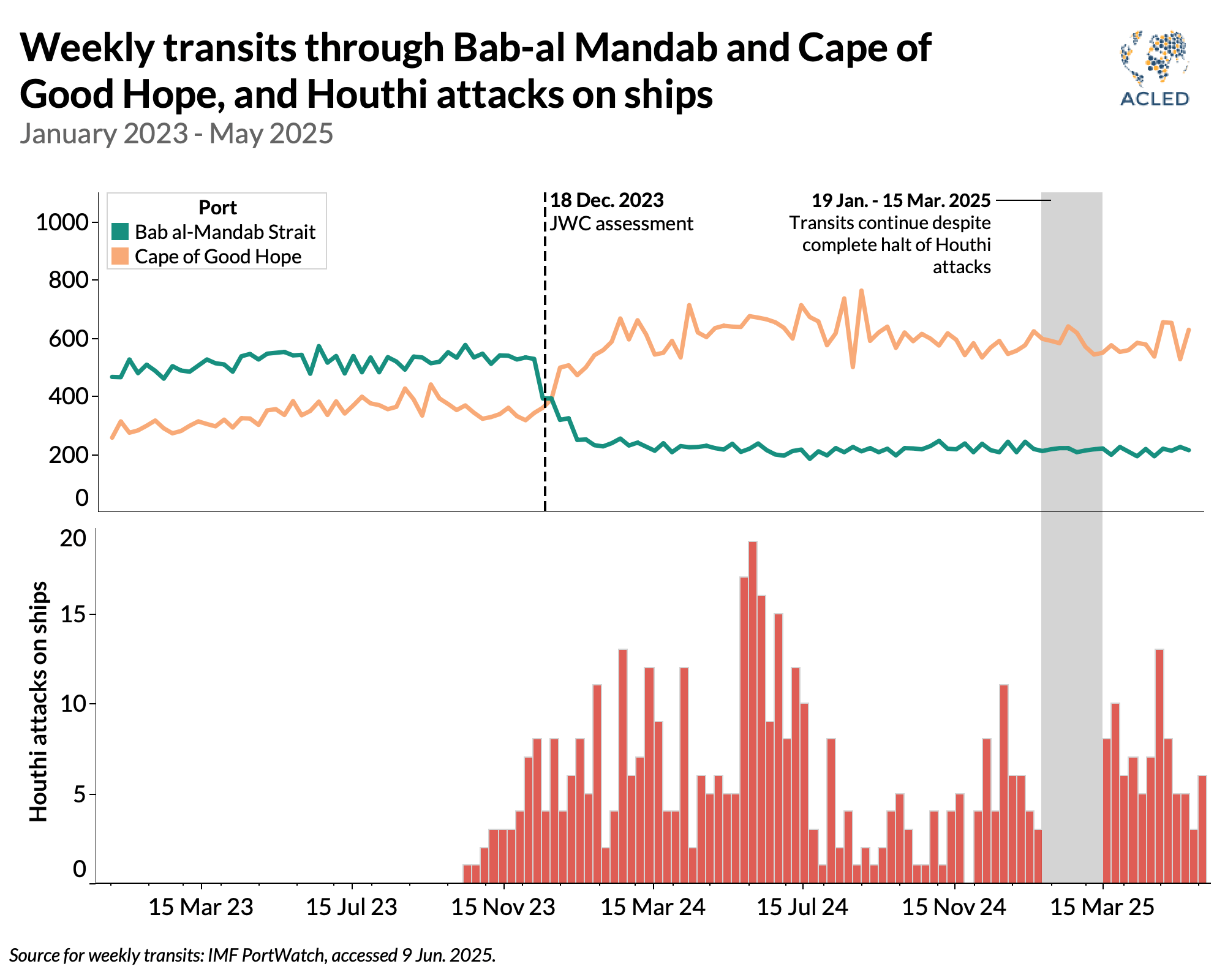

Fluctuations in maritime transits through Bab al-Mandab appear to have been largely unaffected by the intensity of Houthi attacks. Despite major incidents — such as the hijacking of the Galaxy Leader and a peak in attacks in early December 2023 — vessel traffic continued steadily until 18 December. On that day, the Lloyd’s Joint War Committee (JWC) — an influential advisory group focused on risks affecting shipping and maritime insurance — expanded the high-risk area in the Red Sea in response to the expansion of the attacks in the Strait of Bab al-Mandab.43Jonathan Saul, “London marine insurers widen high risk zone in Red Sea as attacks surge,” Reuters,18 December 2023 JWC’s designation caused a sudden drop in transits, and war risk insurance premiums surged by 900% in the weeks that followed.44The Load Star, “Attacks drive up Red Sea war-risk insurance premiums 900%,” 27 February 2024 Concurrently, ships rerouted around Africa through the Cape of Good Hope (see graph below).

Within this framework of heightened risk, the intensity and frequency of Houthi attacks appeared to have little bearing on the volume of maritime transits, which only fluctuated slightly.45Akin to golden shots, major incidents — such as the sinking of the Rubymar and the damage sustained by the Sounion — triggered increases in war risk insurance premiums, yet without significantly affecting the overall number of vessel movements through Bab al-Mandab. See: The Load Star, “Attacks drive up Red Sea war-risk insurance premiums 900%,” 27 February 2024; Al Arabiyya, “Red Sea insurance costs soar as Houthi shipping threats loom, sources say,” 19 September 2024 Even after attacks stopped following the Israel-Hamas ceasefire, transit volumes remained steady. This is explained by two main factors. First, insurance premiums require two to three months of sustained calm to normalize, not just a brief pause in attacks. Second, many vessels continued using alternative routes to avoid paying persistently elevated war risk premiums.

Indeed, the macroeconomic framework created by war risk premiums enables the Houthis’ “marginal gains” strategy. Though they blame the US and financial markets for overreacting, the Houthis benefit from a system where limited attacks can yield outsized effects, due to the West’s low tolerance for collateral damage.

What the US says it’s doing

Direct US-UK intervention against the Houthis began on 12 January 2024, after the group defied an international ultimatum46The White House, “A Joint Statement from the Governments of the United States, Australia, Bahrain, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Germany, Italy, Japan, Netherlands, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom,” 3 January 2024 and carried out the first large-scale attack on US warships in the Red Sea on 9 January.47Saba News, “Text of President Al-Mashat’s speech during his chairing of a meeting of military leaders in Al-Hodeidah Governorate,” 6 January 2024

Operation Poseidon Archer: Shield or sword against the Houthis?

“When you say working, are [the strikes] stopping the Houthis, no. Are they going to continue, yes.”

Former US President Joe Biden, 18 January 202448The Associated Press, “US forces strike Houthi sites in Yemen as Biden says allied action hasn’t yet stopped ship attacks,” 19 January 2024

After launching Poseidon Archer, US Central Command, which is responsible for operations in the Middle East, stated that the airstrikes were intended to “degrade” Houthi military capabilities to conduct attacks on “US and international vessels,”49X @Centcom, 12 January 2024 rather than inhibiting the group’s military capacity altogether. President Joe Biden used even more measured language, stressing that diplomacy had been tried first and vowing to send a message50US Embassy in Panama, “Statement from President Joe Biden on Coalition Strikes in Houthi-Controlled Areas in Yemen,” 12 January 2024 to the Houthis.

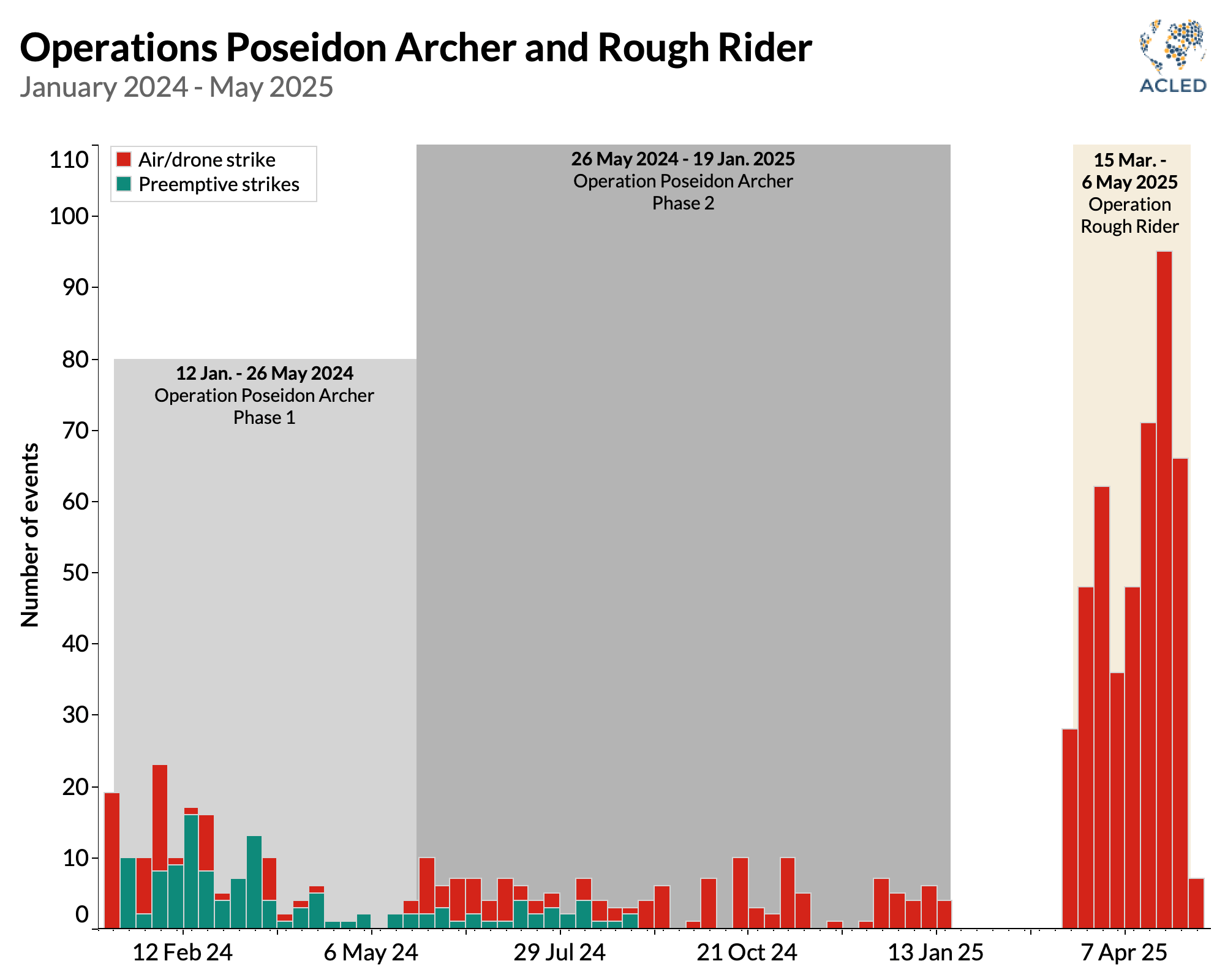

However, seven years of Saudi-led bombing had already shown the limits of airpower against the Houthis, suggesting from the outset that even the waves of US-led strikes between January and March 2024 — targeting radar installations and underground bunkers — were unlikely to be decisive. Though officially aimed at degrading Houthi capabilities, Phase 1 of Poseidon Archer mostly focused on dynamic targeting — preemptively striking the Houthis’ mobile launchers moments before an attack (see graph below) — and largely served a defensive purpose, but failed to deter Houthi attacks.

This defensive stance hinged on several factors, not least a pushback from the progressive wing of the US Democratic Party51Ellen Knickmeyer, “Middle East conflicts revive clash between the president and Congress over war powers,” The Associated Press, 14 March 2024 and a general fatigue around involvement in the Yemen conflict. At the same time, limited US intervention helped keep a door open for diplomacy, while Houthi-Saudi talks continued over the UN peace roadmap announced in December 2023.52Office of the Special Envoy of the Secretary-General for Yemen, “Update on efforts to secure a UN roadmap to end the war in Yemen,” 23 December 2023 However, this ambivalent stance failed to achieve either its public aim — halting Houthi attacks — or its underlying one — securing a peace deal.

Operation Rough Rider: Defeat for Trump or the Houthis?

“[The Houthis] took tremendous punishment. You can say there’s a lot of bravery there. It was amazing what they took. But we honor their commitment and their word.”

US President Donald Trump, 7 May 202553X @WhiteHouse, 7 May 2025

Trump’s actions, too, were laden with contradictions between public messaging and strategic imperatives. During Biden’s term, he strongly criticized Poseidon Archer,54Politico, “Trump criticizes White House for Houthi strikes,” 1 December 2024 portraying it as an unnecessary re-entanglement in the Middle East. Ahead of the 2024 election, he maintained a non-interventionist stance, arguing for a pivot toward the Pacific amid public concern over Poseidon Archer’s mounting costs and US munitions strain.55Beth Sanner and Jennifer Kavanagh, “The Houthis Are Undeterred,” Foreign Policy, 6 January 2025 To US taxpayers, the Red Sea appeared distant, and Trump was eager to avoid seeming like he was aiding the European Union — which he often framed as a competitor.56Jeffrey Goldberg, “The Trump Administration Accidentally Texted Me Its War Plans,” The Atlantic, 24 March 2025

Trump’s first Yemen-related initiative upon returning to office was to upgrade the SDGT designation by re-listing the Houthis as a Foreign Terrorist Organization (FTO) on 22 January 2025.57The White House, “Designation of Ansar Allah as a Foreign Terrorist Organization,” 22 January 2025 This was issued despite the group having halted attacks in the Red Sea and further de-escalating by releasing the crew of the Galaxy Leader.58Saba, “SPC announces release of crew of Galaxy Leader ship,” 22 January 2025 While aimed at curbing Houthi financial resources, the FTO also rendered the UN peace roadmap unworkable, effectively preventing Saudi Arabia from implementing the conditions stipulated in the agreement and eliminating prospects for a short- to mid-term resolution to the conflict in Yemen.

With peace prospects off the table, Trump launched Operation Rough Rider on 15 March 2025 — amid intense debate within the US administration59Jeffrey Goldberg, “The Trump Administration Accidentally Texted Me Its War Plans,” The Atlantic, 24 March 2025 and despite the absence of renewed Houthi strikes in the Red Sea. In public statements, members of the US administration outlined two main objectives for the campaign: to halt Houthi attacks in the Red Sea — particularly those targeting US assets — while re-establishing deterrence and to send a strong message to Iran to cease its support for the Houthis.60Phil Stewart, Mohammed Ghobari, and Gabriella Borter, “US vows to keep hitting Houthis until shipping attacks stop,” Reuters, 17 March 2025

However, the strikes also pursued three secondary objectives: first, a decapitation strategy targeting Houthi leadership; second, the neutralization of the group’s long-range drone and missile capabilities, which were viewed as a long-term threat not only to the Red Sea but to the broader region and US partners; and third, indirect support of the anti-Houthi camp in Yemen.

However self-evident, one point bears emphasizing: Despite his vocal criticism of Biden’s military actions abroad, Trump ultimately adopted a more aggressive approach in Yemen. Rough Rider lasted just 51 days but resulted in 461 airstrike events — a 47% increase compared to Poseidon Archer, which ran for just over a year. Even more striking is the difference in fatalities: Rough Rider reportedly caused an estimated 515 fatalities, compared to just 35 under Poseidon Archer. This heightened lethality is the result of several factors, including loosened rules of engagement61Chris Gordon, “Trump Admin Loosens Rules for US Military Airstrikes,” Air and Space Forces Magazine, 28 February 2025 and a deliberate targeting of civilian objectives with the aim of decapitating Houthi leaders and eliminating high-value targets. The higher number of strikes also caused the campaign costs — estimated by The New York Times at around $1 billion after just two weeks62Eric Schmitt, Edward Wong, and John Ismay, “U.S. strikes in Yemen burning through munitions with limited success,” The New York Times, 4 April 2025 — to spiral out of control, drawing bipartisan scrutiny in Congress.63Jeff Merkley Senator for Oregon, “Merkley, Paul: U.S. Strikes on Yemen Undermine American Law,” 1 April 2025

In terms of achievements, Trump sold the 6 May US-Houthi ceasefire as a major success.64Steve Holland, et al., “Trump announces deal to stop bombing Houthis, end shipping attacks,” 6 May 2025 Indeed, it led to a halt in Houthi attacks on US ships. In terms of eliminating Houthi leadership, despite the at least 30 airstrike events targeting Houthi leaders, they mostly hit residential areas, private vehicles, gatherings, and government infrastructure, and only reportedly killed mid-ranking officers.65Natasha Bertrand, “Cost of US military offensive against Houthis nears $1 billion with limited impact,” CNN, 4 April 2025 Additionally, the objective of fully degrading Houthi capacity was far from being achieved, as the continued attacks against Israel at sustained levels demonstrate. Indeed, the Houthis celebrated the ceasefire as a US surrender.66Saba, “America and the Dimensions of Admitting Defeat,” 26 May 2025

Lastly, US airstrikes targeted Houthi positions on the frontlines — in Lahij, Marib, Taizz, and Hudayda — thereby moving beyond the declared mandate of Rough Rider. These strikes effectively served as indirect support for the IRG, though the Trump administration could not publicly acknowledge this, as openly waging war in support of the Yemeni government would be politically unacceptable.67X @AminHian, 21 July 2025 (Arabic)

Is the Red Sea crisis over?

The Houthis have redefined asymmetric warfare in the region. Their long-range drone and missile capabilities have long challenged regional powers like Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. However, the Gaza crisis has significantly escalated their ambitions, leading to 20 months of attacks that have disrupted global shipping routes, largely undeterred by international maritime patrols and airstrike campaigns.

This incredible deterrent power undoubtedly stems from the advanced technology the Houthis acquired through Iran. Yet, their true success lies not just in their arsenal but in their strategic prowess in wielding media narratives. By masterfully projecting an aura of risk, the Houthis achieve a level of influence that technology and physical attacks alone could never accomplish. From this perspective, even a few symbolic strikes and several ineffective ones, alongside the constant threat of escalation, suffice to perpetuate their strategy of marginal gains.

Israel’s war on Iran opened a new chapter of uncertainty. During the confrontations, the Houthis adopted a low-profile posture, limiting their activity to a single attack on Israel since 13 June and refraining from resuming strikes on commercial shipping — likely in an effort to avoid further escalating regional tensions. Yet, the war demonstrated the fragility of the ceasefire brokered by Trump — limited to US ships in the Red Sea and marred by its failure to fully degrade Houthi long-range capabilities. Indeed, at the earliest convenience, the Houthis threatened attacks on US warships in response to Washington’s strikes on Iranian nuclear facilities.68X @AminHian, 21 July 2025 (Arabic)

The Houthis have already articulated ambitious long-term objectives for the post-Gaza crisis era — primarily, the defeat of Israel and the liberation of al-Aqsa in Jerusalem, alongside securing regional control over territorial waters — and they possess the capacity to resume attacks, even with a low stockpile of munitions. More than ever before, any prospect for lasting stability hinges on a comprehensive approach to the region that addresses not only the immediate escalation but also the broader geopolitical drivers of conflict: from unresolved tensions between the US and Iran to the Houthis’ long-term ideological and strategic ambitions.

Visuals produced by Ana Marco.