On 12 May, the security architecture of Libya’s capital, Tripoli, underwent an upheaval of seismic proportions. That evening, a meeting between the leaders of Tripoli’s main armed groups — purportedly convened to reduce tensions in the city — turned into a deadly shootout for reasons that have not been fully clarified.1Osama Ali, “Calm returns to Tripoli after Kikli’s killing, amid questions about the fate of his forces,” Al-Araby al-Jadeed, 13 May 2025 (Arabic) Among those killed was Abdul Ghani al-Kikli, known as “Gheniwa,” the commander of the Stability Support Apparatus (SSA). Until this happened, the SSA was regarded by many as the capital’s most powerful armed group.2Tim Eaton, “Escalating conflict in Tripoli exposes the realities of false stability – and international neglect in Libya,” Chatham House, 16 May 2025 But, in the months leading up to his killing, tensions between Kikli and Government of National Unity (GNU) Prime Minister Abdulhamid Dbeiba’s camp escalated amid growing competition for control over state institutions and state-owned enterprises.

Following Kikli’s death, a coalition of rival armed groups led by the 444th Brigade launched a well-coordinated lightning offensive to seize SSA headquarters across Tripoli, including in its heavily populated stronghold in the Abu Salim district.3Libya Security Monitor, “Ghinaywa’s death pushes remaining SSA out of capital,” 12 May 2025 By dawn, the Ministry of Defense of the GNU — to which the 444th Brigade is nominally affiliated — announced the conclusion of the offensive:4Ayn Libya, “The Ministry of Defense announces the success of the military operation in Tripoli,” 13 May 2025 (Arabic) The SSA had been wiped off Tripoli’s map.

Building on its successful push against the SSA, on 13 May, Dbeiba’s camp moved against its other main rival in Tripoli, the Special Deterrence Forces (SDF), also known as Rada. At sunset, the 444th Brigade began to engage in armed clashes with the SDF and the SDF-aligned Judicial Police at strategic positions in the city.5Emadeddin Badi, “The Unraveling of ‘Stability’ in Tripoli,” 14 May 2025 By dawn, two of the capital’s other major armed groups — the 111th Brigade and the Public Security Service, led by Abdullah Trabelsi, brother of GNU Interior Minister Emad Trabelsi — rallied to the side of the 444th Brigade. Their coordinated advance forced the SDF to withdraw from key positions in the city, entrench in its eastern strongholds, and rely on allied militias — mainly from Zawiya, west of the capital — to relieve pressure on its western flank.6Libya Security Monitor, “Security situation deteriorates in Tripoli,” 13 May 2025 Almost as quickly as the fighting had begun, however, by noon on 14 May the sides had reached a new ceasefire.7Al Wasat, “The Ministry of Defense of the Dabaiba government announces the start of a ceasefire in Tripoli,” 14 May 2025

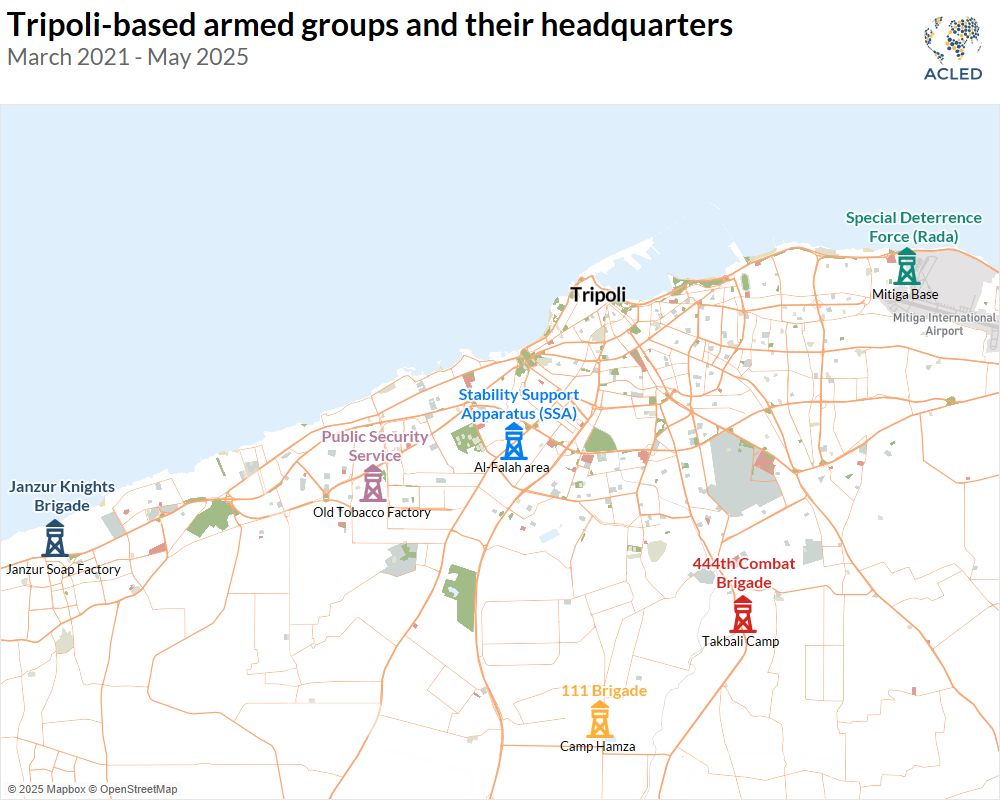

Despite the magnitude of this latest round of clashes, the removal of the SSA from Tripoli and the attempt to follow suit with the SDF reflect dynamics that have long shaped political violence in the Libyan capital. Since the establishment of the GNU in March 2021 following a political process launched by the United Nations mission in Libya, Tripoli’s security architecture has undergone an uneven but steady consolidation around a handful of armed groups (see table and map below). These groups have been locked in persistent intra-elite competition over authority and access to state institutions and rents.8Tim Eaton, “The consolidation of elite network control over Libyan state institutions,” Friedrich Ebert Stiftung, March 2025 Within this fragile accommodation, episodes of infighting remain frequent and tend to follow familiar patterns, often playing out through fluid alliances that at times extend well beyond Tripoli’s boundaries.

| Armed group | Commander | Legal affiliation | Area of influence in Tripoli |

|---|---|---|---|

| Special Deterrence Force (Rada) | Abdurrauf Kara | GNU Ministry of Interior | East and southeast |

| Stability Support Apparatus (SSA) | Abdul Ghani al-Kikli (killed) | GNU Ministry of Interior | Removed |

| 444th Combat Brigade | Mahmud Hamza | GNU Ministry of Defense | Part of the center and the south center |

| 111th Brigade | Abdusalam al-Zubi | GNU Ministry of Defense | Southwest |

| Public Security Service | Abdullah Trabelsi | GNU Ministry of Interior | West |

| Janzur Knights Brigade | Muhamad al-Baruni | GNU Ministry of Interior | Janzur (West) |

| Rahbat al-Dara Brigade | Bashir Khalaf Allah | GNU Ministry of Defense | Tajura (East) |

| Misrata Joint Operations Force | Ibrahim Muhamad | GNU Ministry of Defense | Misrata and access to Tripoli from the east |

| First Support Force | Muhamad Bahrun | GNU Ministry of Interior | Zawiya and access to western Tripoli |

Contested arrests, territorial incursions, and power shifts trigger infighting

From March 2021 through June 2025, ACLED records 64 instances of battles, mainly armed clashes, among Tripoli’s main armed groups (see graph below). These stemmed from 28 distinct outbreaks of violence that collectively spanned 26 days. This infighting is often localized, short-lived, and easily de-escalated. It is also generally linked to attempts at signaling dominance within the blurred space between formal state authority and militia autonomy in which these groups operate and, on occasion, to attempts to renegotiate the existing political order in the context of growing intra-elite competition.

However, the main trigger for armed clashes in Tripoli is contested arrests and captures that escalated into fighting — a pattern ACLED records on nine occasions over the same time period. The most illustrative instance of this dynamic followed the SDF’s capture of the 444th Brigade commander, Mahmud Hamza, at Mitiga Airport in August 2023. This led to clashes between the two groups between 14 and 15 August.9Libya Security Monitor, “Clashes erupt in Tripoli after Rada seizes head of 444 Brigade,” 14 August 2023 The fighting subsided after a ceasefire was brokered between the sides, whereby Hamza was handed over to the SSA and later released.

A revealing manifestation of this pattern involves the SSA and the Judicial Police. The two parties have clashed on three occasions, including with heavy weapons, following disputed arrests. The most recent of these occurred on 25 April 2025, when the Judicial Police and the SDF clashed with the SSA after attempting to arrest a person allegedly linked to the SSA, prompting its intervention.10Libya Security Monitor, “Rada and SSA clash in Tripoli after attempted arrest of militia member,” 25 April 2025

Another major driver of armed clashes in Tripoli is territorial incursions into areas controlled by rival groups or considered neutral. These are often perceived as provocations, which suggests that disputes over perceived jurisdiction remain delicate. On 9 June, the SDF and the Public Security Service clashed in Tripoli after the latter set up a checkpoint in a contentious area of the capital falling within the deconfliction zone established by the May ceasefire agreement.11Libya Security Monitor, “Violence and clashes restart between rival militias in Tripoli,” 9 June 2023 The SDF then responded by expanding its own positions, triggering brief clashes that lasted several hours. This type of retaliation underscores the fragile balance of deterrence that governs Tripoli’s armed ecosystem, where absorbing a blow without responding risks inviting further attacks.

Less frequent, but with far more profound repercussions, are the armed clashes sparked by strategic offensives tied to shifts in power, such as the Dbeiba camp’s successful offensive against the SSA in May and the failed push against the SDF. Prior to these, in August 2022, an attempt by former Prime Minister Fathi Bashagha, appointed by the eastern-based House of Representatives, to unseat Dbeiba in Tripoli also triggered clashes across several neighborhoods.12Raja Abdulrahim, “Clashes Between Rival Militias in Libya Kill at Least 32,” The New York Times, 28 August 2022 Fighting broke out between the Tripoli Revolutionaries Brigade (TRB) and Nawasi Brigade, which backed Bashagha, against the SSA and the SDF, which were both aligned with Dbeiba at the time. Bashagha’s failed bid to enter Tripoli ultimately led to the ouster of the TRB and Nawasi from the capital.13Mustafa Fetouri, “Who fought who in Tripoli last week, and why,” Middle East Monitor, 1 September 2022

Despite the recurrence of clashes, ACLED data show that, except in strategic offensives, fighting in Tripoli tends to be localized in certain neighborhoods and short-lived. Over 80% of incidents last less than a day. This dynamic suggests a broad aversion among armed groups to prolonged and large-scale violence. This is likely driven by strategic and reputational concerns tied to the fact that they are heavily armed, embedded in state structures, and have strong incentives to appear as guarantors of order rather than warlords. An all-out conflict would also risk opening the door to outside actors, most notably the Libyan National Army (LNA), seeking to capitalize on the situation. What emerges is a pattern of calibrated violence, conflict containment, and a shared preference for de-escalation. This is often achieved through back-channel communications and quasi-institutionalized conflict management mechanisms that enable swift compromises.

ACLED records fatalities in about one-third of all outbreaks of violence involving Tripoli’s main armed groups between March 2021 and June 2025. While details about casualties are often scarce, in 60% of the incidents in which fatalities were documented, the people killed were within the ranks of the armed groups involved. The most violent clashes — typically those that escalate beyond their point of origin and involve operations in residential areas, the use of artillery, and indirect fire — tend to result in civilian injuries and deaths, as well as significant property damage.

Militias shift roles as allies, enemies, and mediators amid power struggles

The incidents of infighting between Tripoli’s main armed groups reveal a set of dynamic and situational alliances in which yesterday’s enemy may become tomorrow’s mediator — or ally. In January 2023, for example, the SDF and the 111th Brigade clashed with medium and heavy weapons in the Airport Road area, after which the 444th Brigade deployed in an effort to defuse the situation.14Libya Security Monitor, “Clashes between Rada and 111 Brigade on Airport Road,” 18 January 2023 Just four months later, on 28 May, it was the SDF and the 444th Brigade that clashed, again using heavy weapons, in various areas of Tripoli.15Libya Security Monitor, “Clashes erupt between Rada and 444 Brigade in Tripoli,” 28 May 2023 A few months on, in August — following another confrontation between the same two groups over Hamza’s arrest — the 444th Brigade commander was handed over to the SSA. At the time, the SSA was still seen as a neutral actor. Less than two years later, it would be expelled from Tripoli.

These dynamics suggest a broadly transactional and tactical approach to alliances by the main armed groups in Tripoli, driven in part by a lack of institutional loyalty, temporary shared interests, prevailing power balances, and external pressures. This logic often extends beyond the battlefield as well. In March 2025, a photo taken at a hospital in Rome where GNU Minister of State Adel Juma was being treated after surviving an assassination attempt in Tripoli, pictured, among others, Kikli and Ibrahim Dbeiba, Prime Minister Dbeiba’s nephew and a key power broker in Libya.16Alessia Candito, “Libyan militia leader accused of crimes against humanity returns to Italy,” La Repubblica, 21 March 2025 (Italian) Just a few days later, Ibrahim Dbeiba hosted a Ramadan iftar banquet attended by several prominent militia leaders from Tripoli and nearby areas, including Kikli; Zubi; Trabelsi; the commander of Tajura’s Rahbat al-Dara Brigade, Bashir Khalaf Allah; and the leader of Zawiya’s First Support Force, Muhamad Bahrun.17X @ObservatoryLY, 23 March 2025 (Arabic) Many of them would clash in Tripoli just weeks later.

The swift intervention of leaders from Tripoli’s armed groups — including, at times, those directly involved in fighting — to mediate outbreaks of violence reflects well-established channels of communication and a shared interest in preserving a degree of stability. By stepping in as mediators during moments of crisis, militia leaders can also accrue political capital by positioning themselves as stabilizing actors. In August 2024, amid heightened tensions following the dismissal of Central Bank Governor Sadiq al-Kabir, a broad meeting of armed group leaders from Tripoli and beyond played a key role in containing the situation in the capital.18Libya Security Monitor, “MoI reaches security agreement with key groups over control of the CBL,” 23 August 2024 The meeting included Trabelsi, Zubi, and Abdurrauf Kara from the SDF. In August 2023, at the height of the clashes between the SDF and the 444th Brigade, the decision to hand over Hamza to the SSA was reached in a meeting that brought together nearly all the major power brokers in Tripoli, including Prime Minister Dbeiba, Ibrahim Dbeiba, Trabelsi, Kara, Kikli, Zubi, Khalaf Allah, and Bahrun.19Libya Security Monitor, “Tripoli clashes subside following release of 444 Brigade commander,” 15 August 2024

However, moving beyond these temporary and tactical understandings and resolving deeper-rooted tensions has proven far more difficult. In June 2024, 444th Brigade leader Hamza and the SDF commander Kara met in Tripoli’s Souq al-Juma district in an effort to reconcile. That same month, additional reconciliation meetings paved the way for the TRB leader Ayub Abu Ras and Nawasi Brigade commander Mustafa Qaddour to return to Tripoli. Both left the capital in 2022 after their failed attempt to unseat Prime Minister Dbeiba and install his rival, Bashagha.20Libya Security Monitor, “Shifts in Tripoli’s security dynamics as Rada and 444 attempt to reconcile,” 29 June 2024 Even so, the intense clashes that have since erupted in the city, particularly between the 444th Brigade and the SDF, reveal the limited reach of these reconciliations within Tripoli’s fractured landscape.

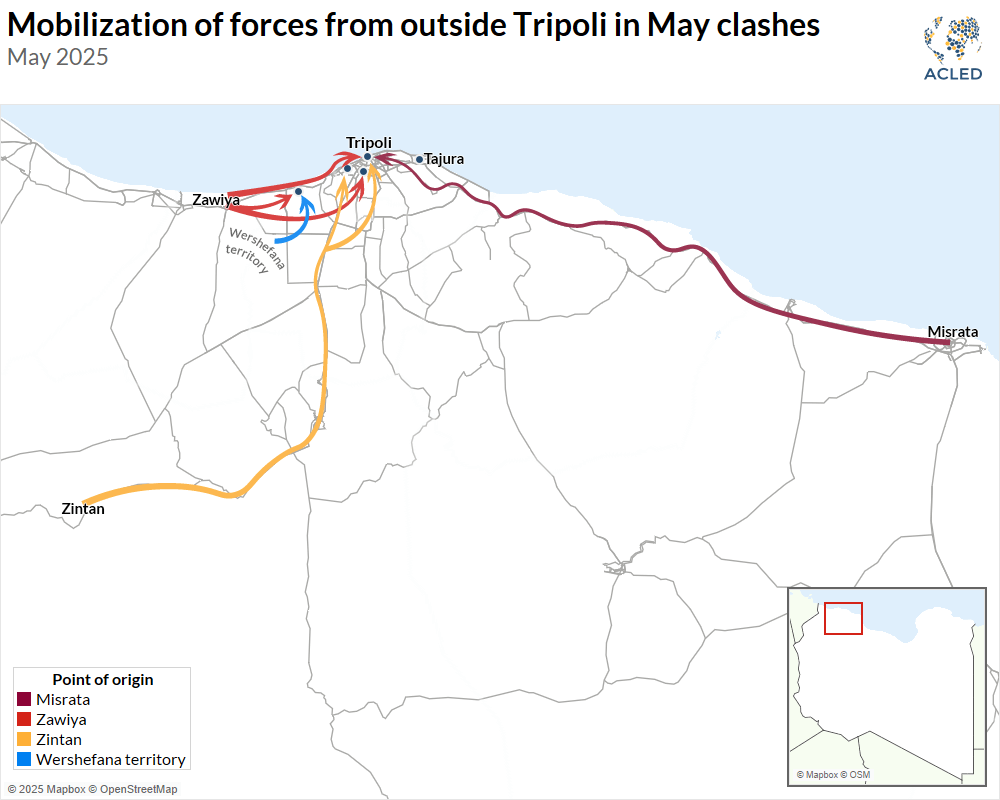

Armed groups call in forces from beyond Tripoli as clashes escalate

In the most serious incidents, particularly strategic offensives, armed clashes in Tripoli have mobilized allied forces from beyond the capital, with tensions also spilling over into nearby cities and feeding back into disputes in Tripoli itself. This dynamic was most evident during the outbreak of violence in May 2025. In the days leading up to the clashes between the coalition of armed groups aligned with Prime Minister Dbeiba and the SSA, ACLED records significant movements of forces from outside Tripoli (see map below). On the SSA side, this included the dispatch of forces from Zawiya, notably some 200 vehicles from Bahrun’s First Support Force.21Libya Security Monitor, “Ghinaywa’s death pushes remaining SSA out of capital,” 12 May 2025 Reinforcements also arrived from Zintan, including around 40 vehicles carrying light and medium weapons, to bolster the ranks of Trabelsi’s Public Security Service.22Akhbar Libya, “Local sources: Military convoys continue to arrive from Zintan toward Tripoli,” 11 May 2025 (Arabic) The Misrata Joint Force (MJF), allied with Dbeiba, sent troops into the capital as well, while forces from Tajura declared a state of general alert.23Libya Security Monitor, “Various militias mobilise around Tripoli amid tensions,” 7 May 2025

The movement of forces was even greater, and more decisive, in the subsequent clashes between the coalition of armed groups aligned with Dbeiba and the SDF. This time, the SDF managed to rally a broad coalition of militias from Zawiya, along with additional forces from Wershefana, home to a powerful armed group.24Libya Security Monitor, “Security situation deteriorates in Tripoli,” 13 May 2025 Their deployment in western Tripoli proved instrumental in opening a new front, especially against the Public Security Service, which was active in the area, thereby relieving pressure on the SDF, whose stronghold lies in the east of the city. The SDF’s ability to mobilize support from armed groups based outside Tripoli was a key factor that enabled it to mount far more sustained resistance than the SSA had.25Emadeddin Badi, “The Unraveling of ‘Stability’ in Tripoli,” 14 May 2025 Meanwhile, the 444th Brigade was also backed by groups from outside Tripoli, like the Misrata Joint Force.

In the other major strategic offensive in Tripoli, during Bashagha’s 2022 attempt to enter the capital, unseat Dbeiba, and install his government, forces from outside the city also played a key role. Bashagha, a Misratan politician appointed by the eastern-based House of Representatives, had the backing of the eastern authorities. During his failed push into Tripoli, he not only relied on local allies such as the Nawasi Brigade and the TRB but also forged support from key armed actors from outside the capital, including from Zintan, Zawiya, and Wershefana. Alongside groups like the SDF and the SSA, Dbeiba also counted on support from other forces from Zintan, Zawiya, and his native Misrata.26Wolfram Lacher, “A political economy of Zawiya,” Small Arms Survey, March 2024

This pattern may even extend beyond western Libya, particularly if Haftar’s LNA, which controls the country’s east and much of the south, perceives vulnerabilities within the coalition of armed groups aligned with the GNU. In May 2025, the mere prospect of LNA involvement was enough to shape dynamics in the capital. Amid rising tensions and armed clashes in Tripoli, the LNA declared a state of alert. It deployed additional forces toward Sirte, located on the ceasefire line established in 2020 after the Second Libyan Civil War, and sent at least three mysterious military cargo flights to Sirte airport.27X @AfriMEOSINT, 14 May 2025 On the ground, its mobilization did not progress beyond these maneuvers, but its actions triggered alarm and were likely a key factor in deterring additional Misratan armed groups from deploying to Tripoli during the offensives against the SSA and the SDF amid concerns over a potential escalation on their eastern flank.28Emadeddin Badi, “The Unraveling of ‘Stability’ in Tripoli,” 14 May 2025

Stability on borrowed time

Since the establishment of the GNU in 2021, the trajectory of armed group dynamics in Tripoli points not to rupture, but to the emergence of a more concentrated yet fiercely contested armed order shaped by fluid alliances and intra-elite competition. While the recent removal of the SSA and the offensive against the SDF may signal further consolidation, these shifts can also be viewed as recalibrations within a system in which short-lived but intense clashes, typically followed by rapid de-escalation, are a tactical means of renegotiating power and access.

Open violence does not appear to serve the shared interests of Tripoli’s main armed groups. This is not due to strategic coordination, but rather a mutual recognition of vulnerabilities, the risks of ungovernability, and external pressures. These dynamics reflect how political change in the capital is shaped less by formal agreements than by the alignments and rivalries of armed actors embedded within state structures. In this context, the GNU’s ability to project power depends less on institutional reform than on its capacity to navigate a fluid and transactional web of armed group alliances.

This system has been held together by transactional arrangements and financial co-optation by the GNU, instead of sustainable institutional reform.29Wolfram Lacher, “Armed group consolidation and ruling coalitions in Libya,” Friedrich Ebert Stiftung, March 2025 Armed groups have been effectively accommodated into Tripoli’s security order through government-linked funding and power-sharing, a strategy that has helped defuse major confrontations. Yet these arrangements remain deeply flawed. A significant drop in oil revenues, particularly amid the GNU’s deepening fiscal crisis, could swiftly unravel them, weakening the government’s ability to manage rivalries.

This risk is compounded by the latent threat that renewed infighting in Tripoli could invite interference by the LNA, whether directly or through allied groups in western Libya. Turkey, which remains deeply embedded in Tripoli’s security architecture and has cultivated increasingly close ties with the Haftars, will also play a key role in shaping any future reconfiguration, whether through deterrence, mediation, or selective backing.30Emadeddin Badi, “Still in the Game: Ankara’s Quiet Pivot in Libya – A View from Tripoli,” 11 June 2025

As Tripoli is once again attempting to recalibrate its security architecture following the SSA’s collapse and the confrontation with the SDF, the foundations of that order remain fragile and highly vulnerable to shocks. Its erosion, or collapse, would carry far-reaching implications for the national balance of power.

Visuals produced by Christian Jaffe.