Q&A with

Héni Nsaibia

West Africa Senior Analyst, ACLED

The Wagner Group announced it was leaving Mali in early June after over three years of operating in the country alongside the Malian military (FAMa) against jihadist insurgents. In this Q&A, ACLED Senior Analyst for West Africa Héni Nsaibia breaks down how the mercenary group has affected violence and politics in Mali and what these changes mean for Russia’s involvement in Africa.

Is Wagner’s exit from Mali a reaction to the heavy losses it suffered while fighting insurgents with the military? Or is it just Moscow adjusting its Africa policy and erasing the Wagner label?

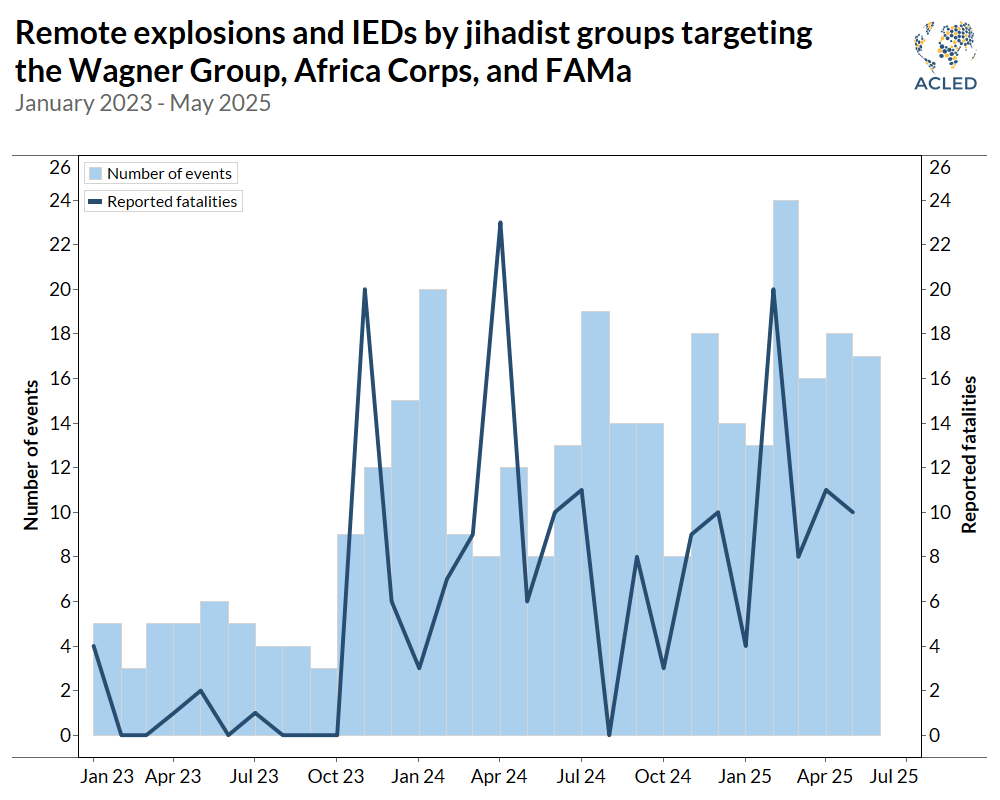

While it is true that the number of casualties in Wagner’s ranks gradually increased alongside a growing number of militant victories against the group and the FAMa forces as jihadist insurgents increasingly used explosive devices (see graph below), Wagner’s withdrawal from Mali appears to be more a matter of optics and political recalibration than a military setback.

The overall picture points to a strategic rebranding by Moscow. With the Wagner name severely tarnished after the June 2023 mutiny and former leader Yevgeny Prigozhin’s death in August that year, Russia is likely consolidating its foreign military ventures under formal state control by erasing the Wagner brand while retaining its core functions under a new name of Africa Corps. This way, Moscow can distance itself from the mercenary narrative while maintaining a strong regional presence.

Wagner said that it had accomplished its mission when it left Mali. Has it been successful in Mali, and what legacy is Wagner leaving behind?

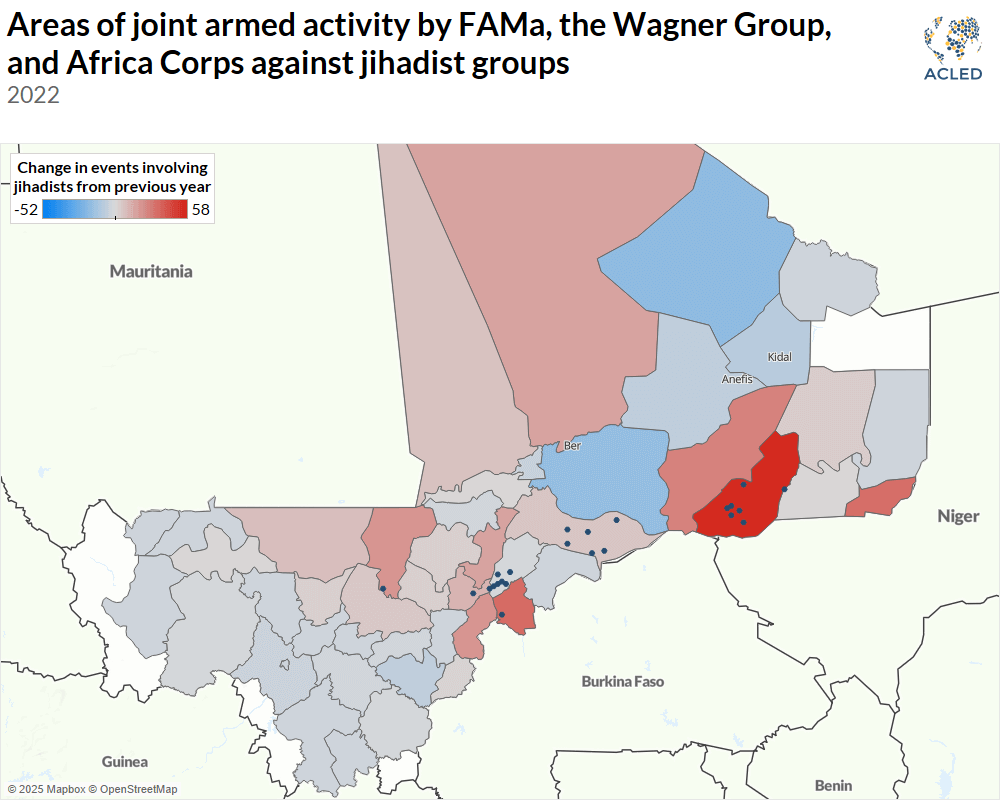

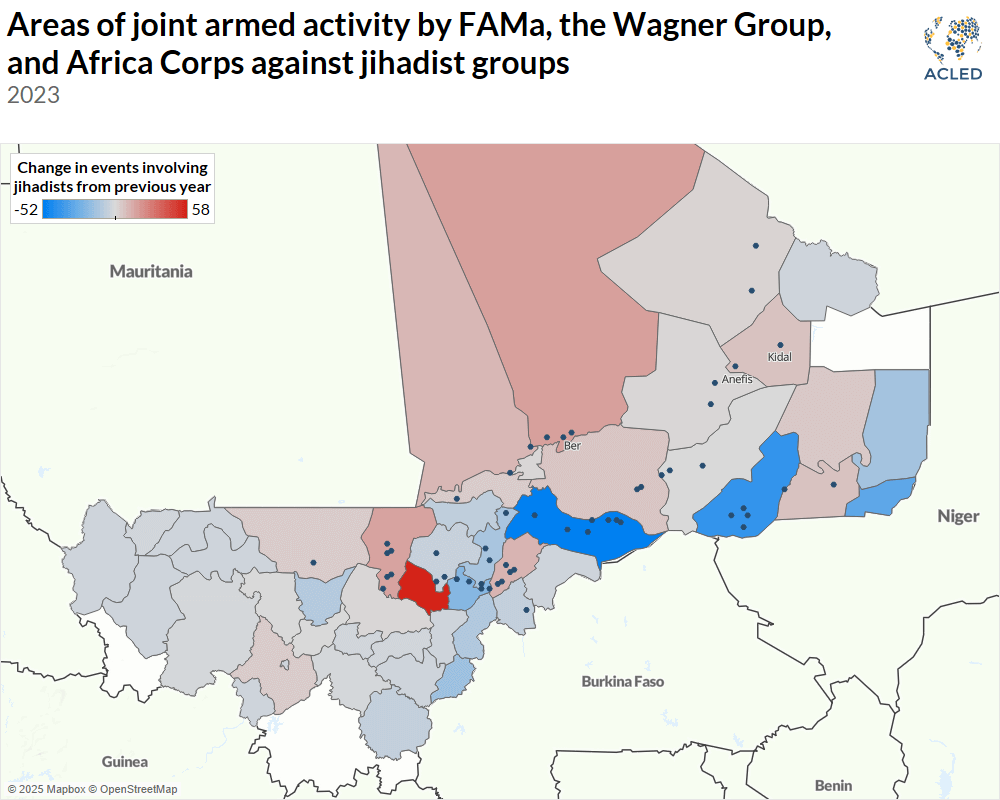

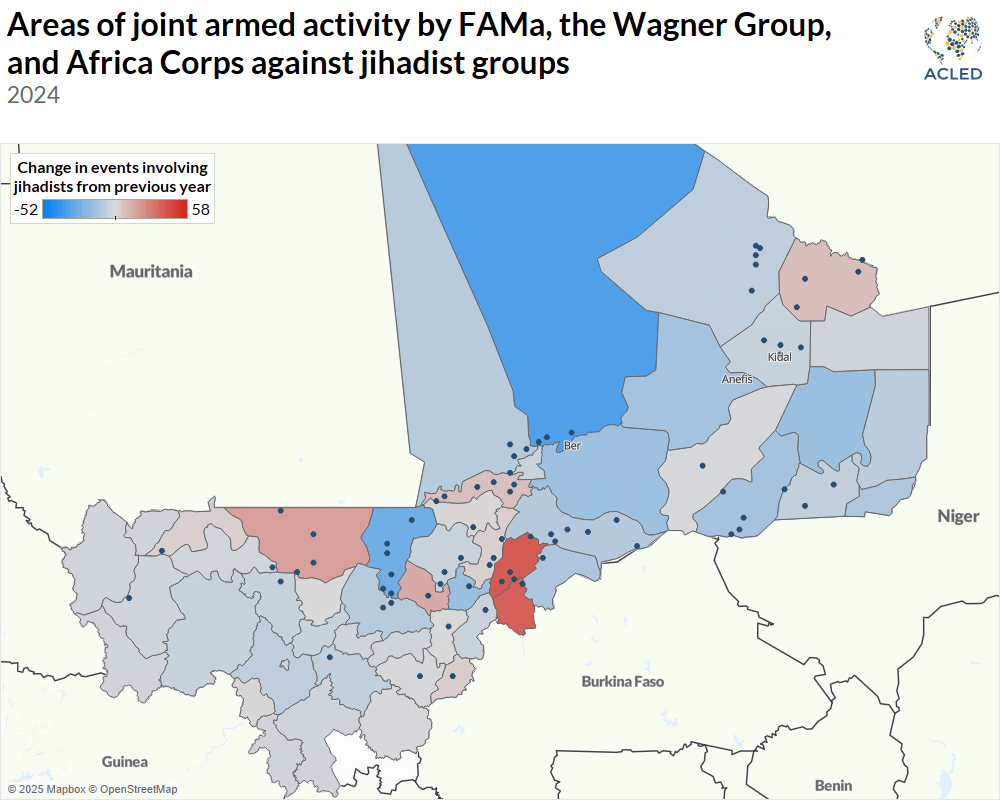

The claim of “mission accomplished” serves more to save face than to assess the actual military outcomes in Mali.1Filipp Lebedev, et al., “Africa Corps to stay in Mali after Russia’s Wagner mercenary group leaves,” Reuters, 6 June 2025; Guillaume Vénétitay, “Torture and Forced Disappearances: Inside Wagner’s Secret Prisons in Mali,” Forbidden Stories, 12 June 2025; X @stopwagnergroup, 10 June 2025 Rather, Wagner’s successes are mixed at best, as it leaves behind a country in a state of sustained instability and fragmentation. However, Wagner mercenaries have enabled FAMa to return to areas where they would have had severe difficulties if they were to operate alone and to achieve some tactical and strategic victories, notably the recapture of rebel strongholds, including Kidal, Ber, and Anefis (see maps below).

The group has also helped the junta consolidate its power as it temporarily pushed back the threat of insurgents in some areas and changed the balance of fear. This was true particularly in the eyes of the civilian population, which began to fear Wagner more than the jihadist groups.2Jeune Afrique, “Wagner in Mali: Populations in the North and Center testify to their daily fear,” 11 April 2025 (French) However, despite its presence, Mali saw continued attacks and militant expansion (including in the south and west of the country and around the capital, Bamako), an ongoing humanitarian crisis, and allegations of widespread human rights abuses and atrocities.3Human Rights Watch, “Mali: Atrocities by the Army and Wagner Group,” 12 December 2024

Wagner’s actual contribution to Mali was more political than military; the group solidified the country’s pivot away from Western allies and facilitated a stronger partnership with Russia. Regardless, it has left Mali a deeply fragmented country.

Africa Corps will replace Wagner in Mali, supervised by Russia’s Defense Ministry. What is the significance of this?

This transition marks a somewhat strategic shift from private, semi-governmental paramilitary operations to state-sanctioned military partnerships. Africa Corps is intended to give Moscow greater control over operations, as well as potentially more international legitimacy and fewer legal and reputational risks. It also signals Russia’s intent to institutionalize its military engagement in Africa and ensure that it aligns with official foreign policy objectives.

Why has Mali pivoted toward Russia?

Mali’s turning to Russia expresses its frustration with its Western partners, particularly France, and its desire for sovereign control over its security policy. The 2020 and 2021 military coups accelerated this change, as the ruling junta sought partners more aligned with its political priorities and less critical of its undemocratic rise to power. Even in the eyes of the Sahelian population, a decade of Western-backed counter-terrorism and peacekeeping missions has not significantly improved the security situation in the country, as conflict and violence spread throughout the region.4Naomi Moreno-Cosgrove, “France’s unattainable counterterrorism mission in the Sahel,” Real Instituto Elcano, 6 April 2022 The junta also views Russia as less politically intrusive and more willing to provide immediate military assistance, including aerial assets and weaponry, without being tied to democratic or human rights conditions.5Mark Banchereau and Jessica Donati, “What to know about Russia’s growing footprint in Africa,” Associated Press, 6 June 2024 This realignment also serves to symbolically reaffirm Mali’s independence from former colonial and Western influence while securing the support of a global power that supports military-led governance models.

Are we likely to see Wagner exit other African countries?

With time, yes, that’s possible. Without Prigozhin’s leadership and the Kremlin’s patronage, Wagner’s structure is not sustainable. In countries such as the Central African Republic, a similar transition could occur if Russia continues to absorb Wagner’s assets and personnel into more official entities like Africa Corps or similar units affiliated with the Ministry of Defense. However, this process could vary depending on local dynamics and the host governments’ dependence on Wagner’s mercenaries.

With Wagner being replaced by Africa Corps, what is likely to change in Russia’s activities in the Sahel and other parts of Africa?

We can expect a more formalized, state-supported Russian presence. Operations could shift from frontline combat to a more strategic role, encompassing arms deals, military training, intelligence support, and regime protection. Africa Corps could also coordinate more directly with the Russian foreign service, helping anchor Russia within partner states’ military institutions and reducing the transactional and opaque footprint left by Wagner.

Does Russia’s pivot to Africa Corps indicate a shift from Wagner-style battlefield engagement to training, equipment, and protection services for authoritarian regimes?

In part, yes. Africa Corps can still conduct combat operations, but its focus will likely be on regime stabilization, infrastructure protection, and strategic influence. This is in line with Russia’s overall goal of being seen as a reliable alternative to Western military partners, especially by governments affected by insurgencies or political isolation.6Paul Stronski, “Russia’s Growing Footprint in Africa’s Sahel Region,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 28 February 2023 The Africa Corps model is more sustainable and politically controllable than Wagner’s riskier, high-profile deployments.