Monitoring Disorder in Nepal

A Joint ACLED, COCAP, and CSC Report

5 May 2022

ACLED has worked with partners at Collective Campaign for Peace and the Centre for Social Change to complete a supplemental coding project enhancing our coverage of political violence and demonstration activity across Nepal. Drawing on the new data, this joint report examines political violence and demonstration patterns since the first democratically elected government under the new constitution came to power in 2018 and assesses the potential for disorder during the upcoming elections.

Scroll down to read online.

Introduction

Nepal is holding elections across all levels of government in 2022. It is only the second time elections are being held since the promulgation of Nepal’s much-contested constitution in 2015. The outcome of these elections is likely to shape how lingering issues over the constitution and its provision of autonomy and rights for ethnic groups, including the people of Madhesh province, are addressed. Elections for Nepal’s National Assembly, the upper house in parliament, were already held on 26 January in which the Nepali Congress (NC)-led alliance made the biggest gains while the Communist Party of Nepal (Unified Marxist–Leninist) (CPN (UML)) lost seats. Local-level elections will be held on 13 May amid concerns that intra-party rifts will pose the biggest security threat for upcoming elections (Kathmandu Post, 6 April 2022).

Rivalries within and between political party factions vying for influence can often lead to violence in Nepal. As no single party holds the majority in parliament, alliances tend to form and splinter throughout election periods. The fragile nature of these alliances and coalitions, along with groups dissatisfied with the incomplete implementation of the restructuring of the state to provide more rights and autonomy to ethnic groups, raises concerns over the possibility of increased political disorder in the coming year. Using new data collected with ACLED’s local partners — Collective Campaign for Peace (COCAP) and Centre for Social Change (CSC) — this report examines political violence and demonstration trends in Nepal from 2018 to the present.

Improving ACLED’s Nepal Dataset

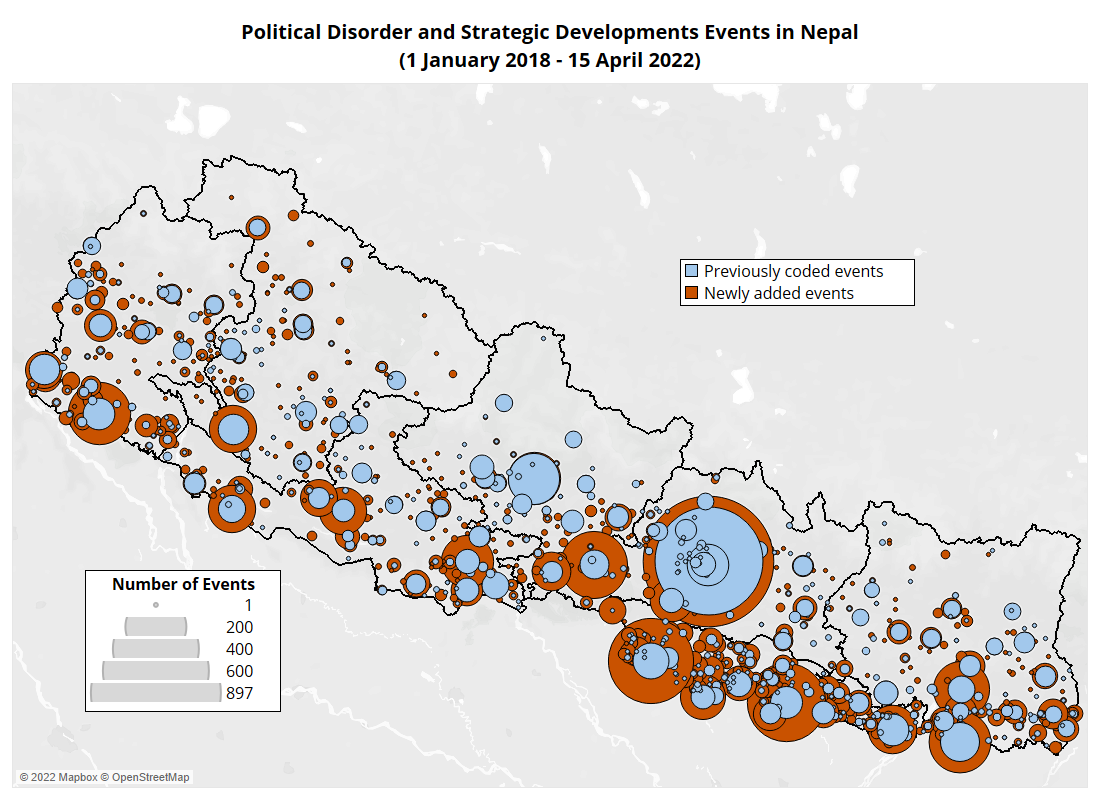

ACLED has completed a supplemental coding project covering local partner data and new local and subnational sources. The new supplemental data add over 8,700 events to ACLED’s Nepal dataset (see map below).1ACLED’s Nepal dataset contains data from January 2010 to the present. The recently completed supplemental coding project covers data for Nepal from 2018 to the present. ACLED publishes data coming from new sources in multiple tranches, with the initial tranche published once a source is back-coded to 2018. For an overview of how and when new sources are added to ACLED coverage, and the implications users should keep in mind when using ACLED’s historical data, see Adding New Sources to ACLED Coverage. ACLED has not yet started a supplemental project for data prior to 2018. The data greatly expand the number of demonstration events captured by ACLED in Nepal, with demonstrations accounting for over 80% of newly added events.

The completion of the supplemental project added over 20 local and subnational sources in the Nepali language, spanning all seven provinces. This allows for more extensive coverage of remote hilly and mountainous districts which are undercovered in the national English language media. Thus, as part of its weekly real-time data collection, ACLED now covers 40 sources for Nepal, ranging from local newspapers to international media primarily in English and Nepali.

ACLED has also drawn data from one of its local partners, COCAP, which established the Nepal Monitor in November 2014. The monitor is an online system designed to alert local organizations about human rights and security incidents in their areas of operation. ACLED has drawn on incident reporting from the monitor to code events at the local and subnational levels.

Researchers from the CSC, a Nepal-based social think tank and ACLED partner, aided in the sourcing and coding of the supplemental data for ACLED.

National Trends: Increasing Demonstrations, Declining Political Violence

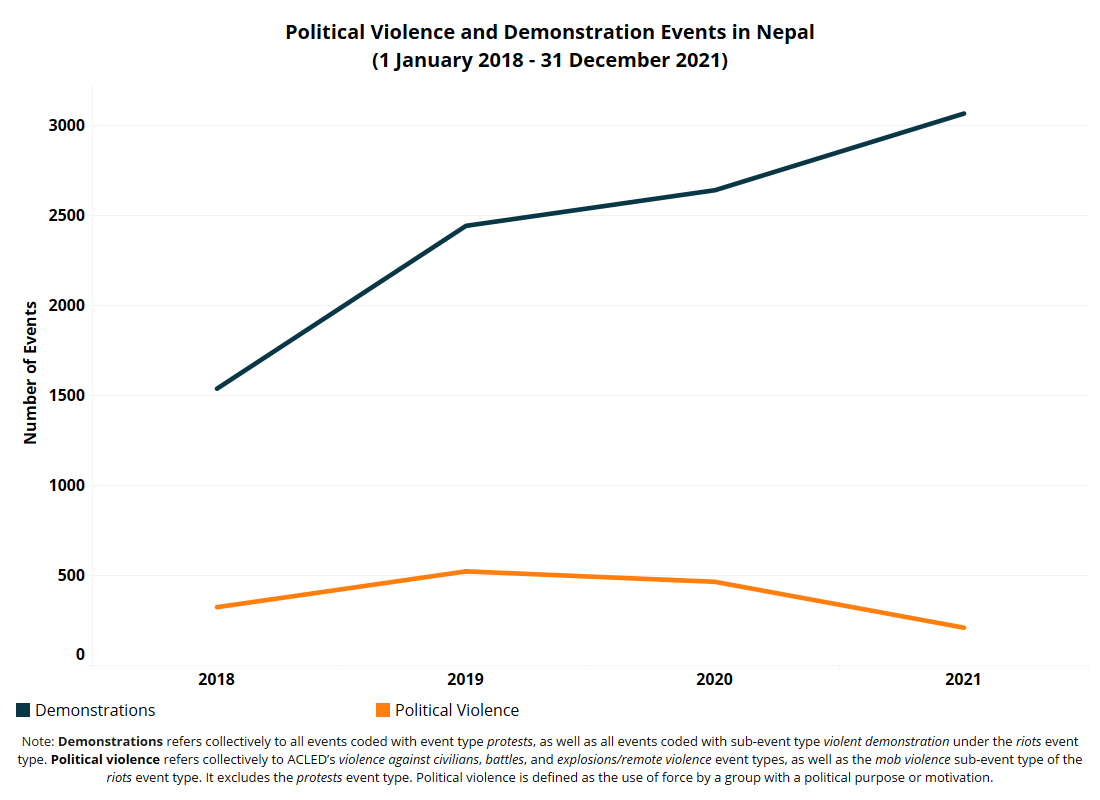

While overall political violence2Political violence refers collectively to ACLED’s violence against civilians, battles, and explosions/remote violence event types, as well as the mob violence sub-event type of the riots event type. It excludes the protests event type. Political violence is defined as the use of force by a group with a political purpose or motivation. For more on event types, sub-event types, and interaction terms used in the ACLED data, see the ACLED Codebook. in Nepal has declined since 2019, demonstration activity has increased year-on-year since 2018, with the highest number of demonstration events recorded in 2021 (see figure below). ACLED records a more than 16% increase in demonstration events in 2021 compared to the year prior, and an increase of nearly 100% compared to 2018.

The increase in demonstration events in 2021 was largely a result of demonstrations concerning the dissolution of parliament, a shift towards mobilizing for demonstrations by the Netra Bikram Chand-led Maoist group, and demonstrations surrounding the ratification of the Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) Nepal Compact. Each of these demonstration issues, along with shifting patterns of disorder, will be explored in greater detail below.

Political Disorder Arising from the Dissolution of Parliament

The new constitution of Nepal came into effect on 20 September 2015, following nine years of transitional governance in Nepal after the 2006 end to the country’s civil war. The constitution transformed the previous system of governance from a unitary state with decentralized local representation to a federal democratic republic with three tiers of government: local, provincial, and federal. The first elections for the newly established local, provincial, and federal legislative bodies were held in 2017. Left-alliance parties, including the CPN (UML) and the Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist Centre), the biggest faction of former Maoist rebels, won a majority in the federal parliament, as well as in six out of seven provincial parliaments. Following the victory, in February 2018, the first democratically elected government under the new constitution of Nepal was sworn in and the left-alliance parties merged to form the Nepal Communist Party (NCP) in May 2018. The party merger ensured that the left-alliance government would enjoy a nearly two-thirds majority in parliament (My Republica, 18 May 2018).

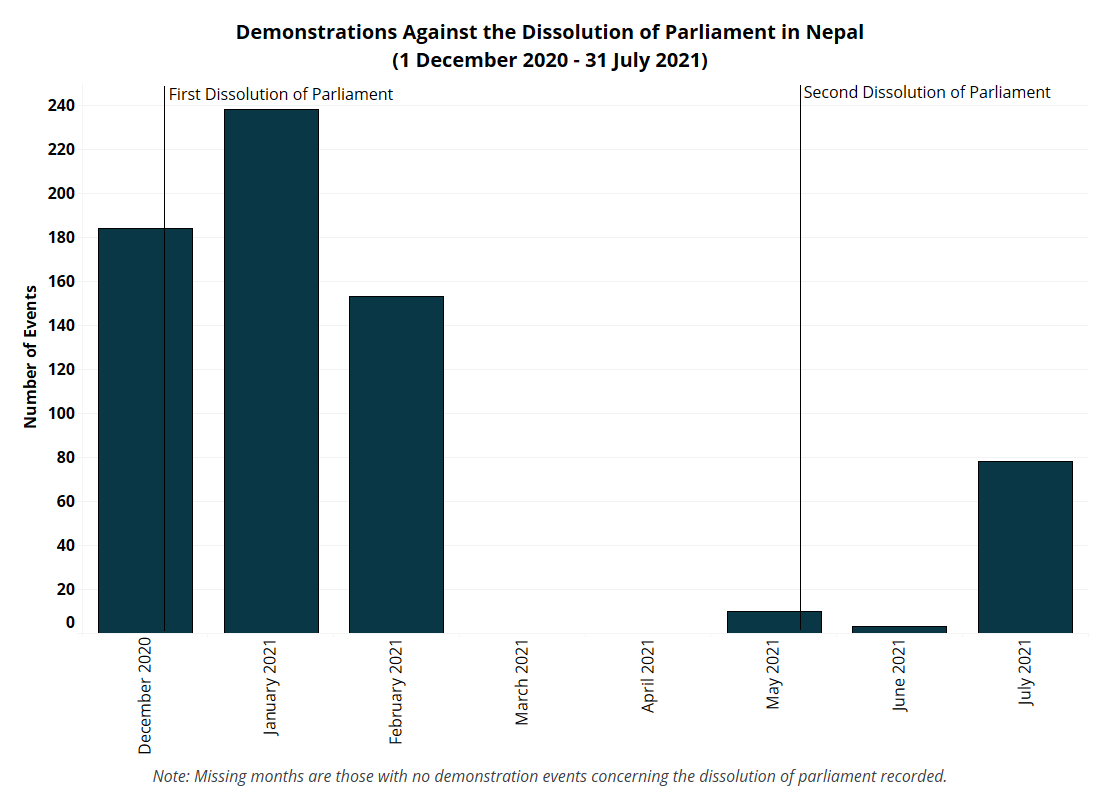

Yet, internal disagreements within the coalition led to the dissolution of the parliament and nationwide demonstrations during 2020 and 2021 (see figure below). Then-President Bidya Devi Bhandari dissolved the House of Representatives on 20 December 2020 on the advice of then-Prime Minister KP Sharma Oli, and announced general elections for April and May 2021, at least a year ahead of schedule (Al Jazeera, 20 December 2020). While the prime minister claimed fresh elections were needed to iron out internal conflicts within the ruling NCP, Oli’s critics accused him of corruption, mishandling the COVID-19 pandemic, and shifting support to China away from Nepal’s traditional partner India (Deutsche Welle, 29 December 2020). After the dissolution of parliament, thousands staged daily demonstrations, denouncing the move as unconstitutional (Reuters, 22 January 2021). The demonstrations continued into early 2021. Demonstrations were held by opposition parties, student groups, and a faction of Oli’s own party led by former prime ministers and NCP leaders.

After dozens of petitions were filed against the prime minister in the Supreme Court of Nepal (CNN, 31 December 2020), on 23 February 2021, the judicial body reinstated parliament, terming the dissolution unconstitutional (Reuters, 23 February 2021; New Indian Express, 23 February 2021). Furthermore, on 7 March 2021, the Supreme Court annulled the party registration of the ruling NCP as another party with the same name was already registered with the election commission of Nepal (Kathmandu Post, 7 March 2021). This decision effectively split the ruling NCP into Unified Marxist-Leninist and the Maoist Centre, the same two parties which had merged in 2018 to form the NCP (Kathmandu Post, 7 March 2021). With the reinstatement of parliament and the split of the ruling party, Prime Minister Oli sought a vote of confidence in parliament to remain in power, a vote which he lost (Kathmandu Post, 11 May 2021).

On 21 May 2021, for the second time in five months, the president dissolved parliament, stating that neither the caretaker government nor the opposition had a majority to form a new government (Al Jazeera, 22 May 2021). The move triggered fresh widespread demonstrations by political parties claiming the decision was unconstitutional, and demanding parliament be restored and headed by the main opposition candidate, Sher Bahadur Deuba (Al Jazeera, 26 May 2021). Both supporters of Oli and the opposition rallied for their demands before the Supreme Court ruled on the case. On 12 July 2021, the Supreme Court reinstated the House of Representatives and ordered that Deuba, the chairman of the opposition NC, be appointed as prime minister (Al Jazeera, 12 July 2021).

With the reinstatement of parliament, Deuba formed a coalition government and the constitutional crisis borne out of the dissolutions of parliament subsided (Himalayan Times, 12 July 2021). Despite early disagreement over key ministry portfolios (Nepal Live Today, 13 August 2021), the coalition has held into early 2022, winning 18 out of 19 seats in the National Assembly elections in January 2022.

In Focus: Inter- and Intra- Party Violence

Despite the relative stability thus far of the coalition government, political jostling is expected ahead of municipal elections on 13 May 2022, and provincial and federal assembly elections that have yet to be scheduled. As no single party is expected to hold the majority, new electoral alliances and coalitions are likely to be formed before the elections (Kathmandu Post, 2 March 2022). Inter-party and intra-party rivalries are likely to persist, possibly leading to violence.

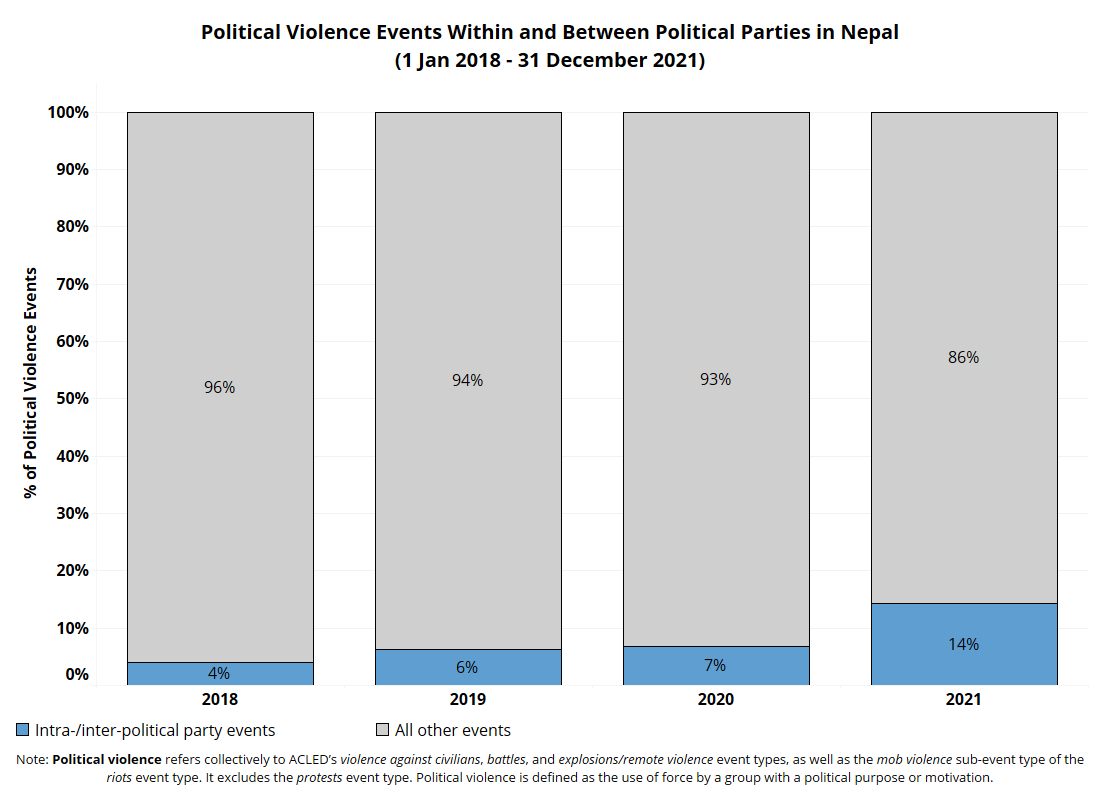

Since 2018, the percentage of political violence within and between political parties has increased relative to the total political violence recorded in Nepal (see figure below). Since September 2021, when parties began holding their local level conventions (Nepalnews, 2 September 2021), intra-party violence during the local level conventions of the NC, CPN (UML), and the wings of their organizations has been reported in all provinces except Gandaki province. Political violence among political parties spiked in November 2021 owing primarily to intra-party clashes during NC district conventions in five provinces, including Madhesh and Lumbini. Recently, intra-party violence was reported during the CPN (UML) district conventions in Parsa and Kailali districts in January 2022, and in early March 2022 during the NC district convention in Siraha.

Shifting Tactics: Demonstrations by the Netra Bikram Chand-led Maoist Faction

While the major factions of the Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist) (CPN-M) joined mainstream politics in the lead-up to the 2017 elections, a group led by Netra Bikram Chand, one of the two main CPN-M militia commanders, accused the Maoist establishment of deviating from their civil war objectives in accepting parliamentary democracy over people’s revolution (Indian Express, 26 June 2012; Al Jazeera, 2 October 2018). The group subsequently expressed opposition to the government and reforms implemented under the new constitution through small-scale explosions, destruction of property targeting local government offices, telecommunication towers, and development projects, and violence against local government officials.

Perhaps in an effort to avoid closing the political space for negotiation, successive governments had been lenient towards the Chand group and their propensity for violence. This dynamic shifted in February 2019 following a bombing claimed by the group in Lalitpur city, Bagmati province, which killed one civilian. The bombing targeted the headquarters of a telecommunications giant with significant foreign investment that owed more than half a billion dollars in taxes (Kathmandu Post, 26 December 2019). While the Chand group apologized for the death of the civilian, the government banned the group and formed a special task force to monitor and arrest cadres of the Chand-led Maoist party (My Republica, 17 March 2019).

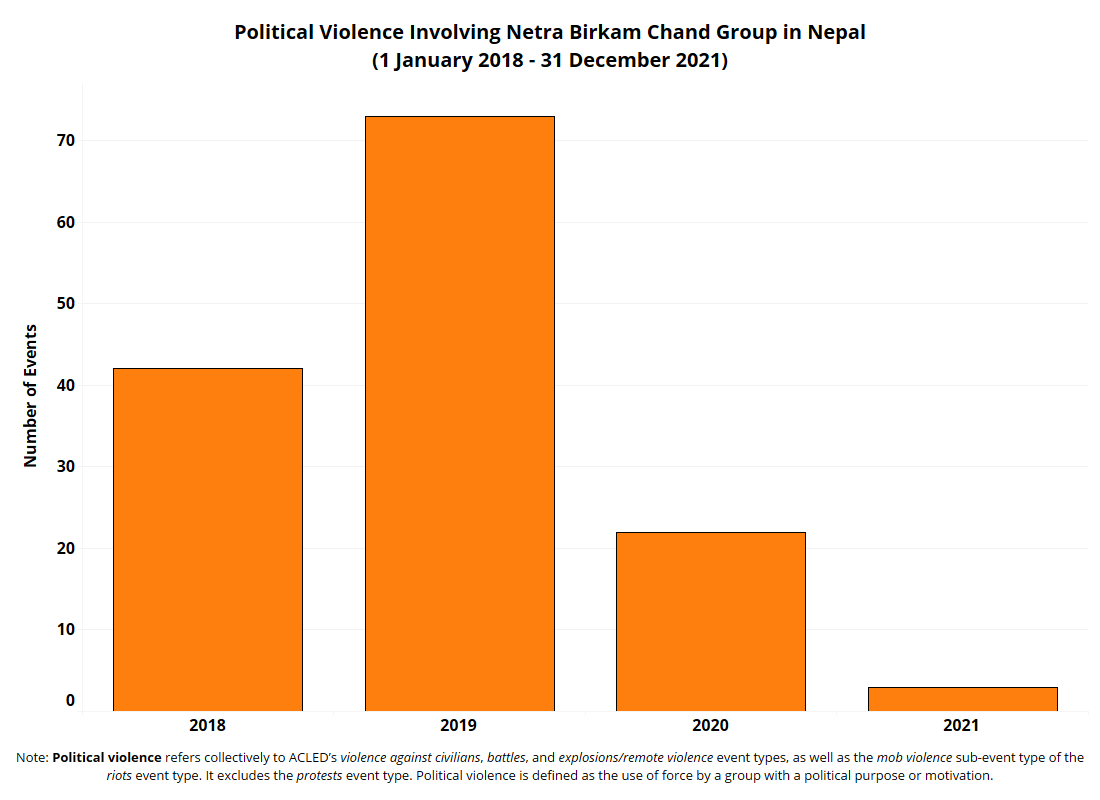

After police arrested several key leaders of the party from across the country (My Republica, 13 May 2019), the party called for a bandh3Bandhs are strikes that are often accompanied by demonstration actions and can be peaceful or violent. They are typically called by political parties. in several districts. Armed clashes also ensued between the group and security forces. The government crackdown and the group’s response led to a nearly 74% increase in the number of political violence events involving the Netra Bikram Chand group in 2019 compared to the year prior (see figure below).

At least three senior leaders of the group were killed in armed clashes with security forces and hundreds of central leaders and cadres of the group were arrested by early 2020 (Kathmandu Post, 12 July 2019; My Republica, 12 January 2021). Some leaders joined other communist political parties in return for amnesty, weakening the organizational structure of the Chand faction (My Republica, 12 January 2021). Thus, in 2020, the number of events of political violence involving the group decreased by over two-thirds compared to 2019 (see figure above). Two years after the group was banned, in March 2021, a three-point peace agreement was signed between the government and the group (Himalayan Times, 5 March 2021). The government agreed to lift the ban on the group, release all arrested party members, and drop all legal cases against them, while the group agreed to give up all violence and join mainstream politics.

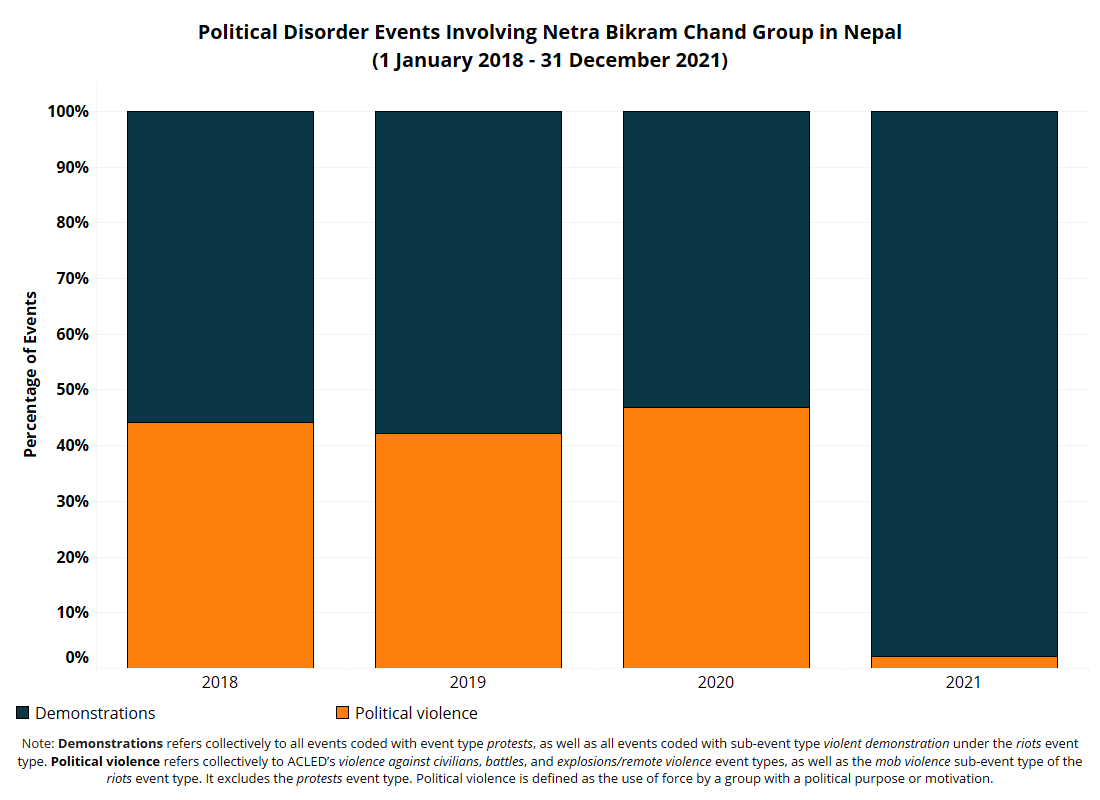

In 2021, only 2% of disorder events involving the group captured by ACLED were political violence events (see figure below). The group has instead engaged in demonstrations to convey their political positions, and was notably involved in demonstrations against the government’s ratification of the MCC in February 2022, though some of these events did turn violent (for more, see section below). Chand has asserted that the MCC is a “new form of imperialism” and part of an American strategy to use Nepal’s territory for military components aimed at containing China (Makalu Khabar, 4 March 2022).

The new government led by the NC that came to power in July 2021 is facing challenges in implementing the three-point agreement with the Chand faction. The Chand-led group held nationwide demonstrations in October 2021, demanding the release of their party cadres and calling for all charges filed against party members to be dropped in line with the peace agreement. In the upcoming elections, the Chand group will allow its leaders and cadres to run as independent candidates (Setopati, 28 March 2022). This represents a marked change from the last elections in 2017, when the group spurned the elections and was responsible for some of the deadly violence that Nepal witnessed (New York Times, 25 November 2017). The extent to which the public will support Chand-backed candidates remains to be seen.

Geopolitics and the Millennium Challenge Corporation Demonstrations

Nepal’s geographic location between China and India has also led to political disorder in recent years amid geostrategic positioning. A driver of widespread mobilization has been discontent over the MCC Nepal Compact agreement. The MCC compact agreement is a $500 million grant agreement signed with the United States in 2017, which provides for infrastructure construction in Nepal (Himalayan Times, 15 September 2017). Nationwide demonstrations erupted in June 2020 over concerns it would be ratified by the parliament and, in turn, undermine the country’s sovereignty.

The project became a politically contested issue following a visit to Nepal by State Department officials in May 2019. During the visit, they discussed links between the MCC’s ambitions for regional connectivity and the goals of the US Indo-Pacific Strategy aimed at counterbalancing China’s influence in the region (Himalayan Times, 15 May 2019). The MCC was registered in federal parliament for ratification in July 2019, but pushback from communist leaders, including some within the ruling NCP, delayed the ratification (Kathmandu Post, 9 January 2020). Several Nepali communist parties, including factions within the NCP sympathetic to China, began mobilizing against the MCC through demonstrations in early 2020. A NCP task force within the ruling party concluded that the MCC was “closely linked to the US government’s security goals and programs” (Khabar Hub, 1 May 2020). They also claimed that some of the agreement’s clauses would prevail over existing Nepali laws, thus jeopardizing Nepal’s sovereignty (Al Jazeera, 20 February 2022).

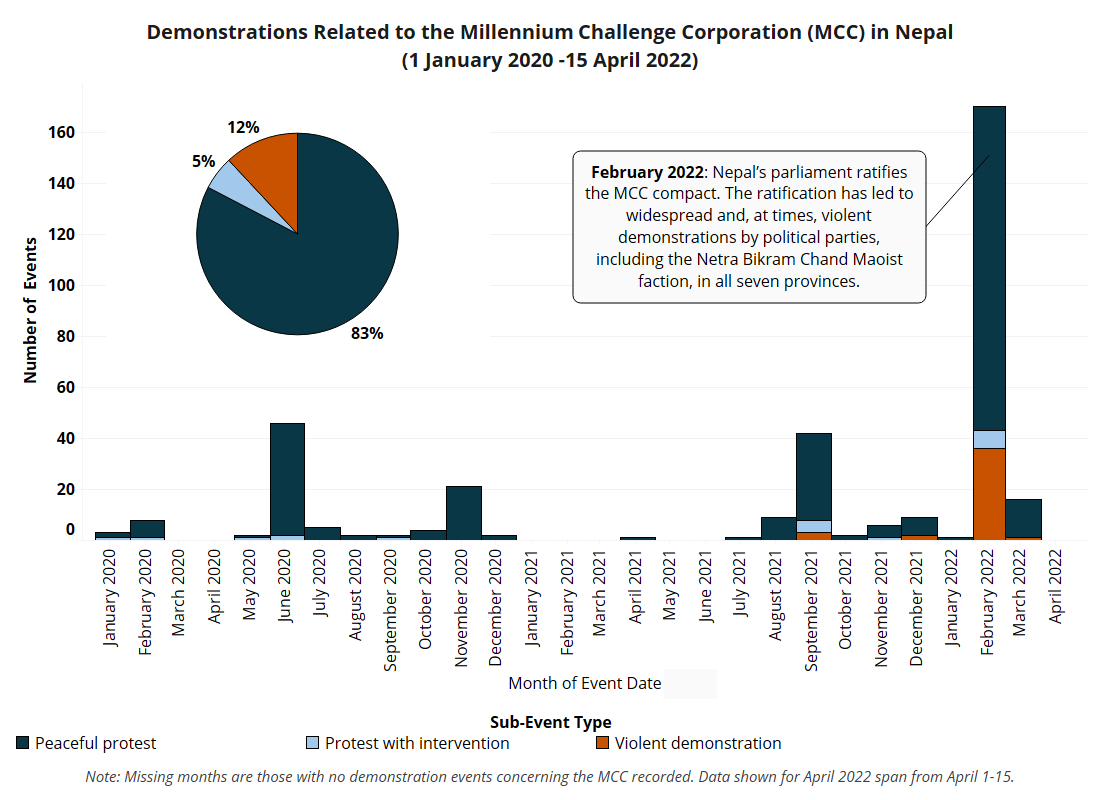

As the 30 June 2020 deadline neared for ratification of the project by the parliament, nationwide demonstrations were held (Kathmandu Post, 23 June 2020). Demonstrations continued throughout the remainder of 2020, increasing again in November 2020 with the National People’s Front (RJM), a fringe communist political party, organizing demonstrations in five provinces. Demonstrations against the MCC decline following the dissolution of parliament as the focus shifted to the constitutional crisis.

MCC-related demonstrations reignited again in August 2021, following the reinstatement of parliament, and reached a peak in February 2022 (see figure below), as Nepal’s parliament ratified the MCC compact. The ratification has led to widespread and, at times, violent demonstrations by political parties, including the Chand Maoist faction, in all seven provinces. Since January 2020, ACLED records over 350 demonstration events concerning the MCC, and over 12% involved reports of violent or destructive activity.

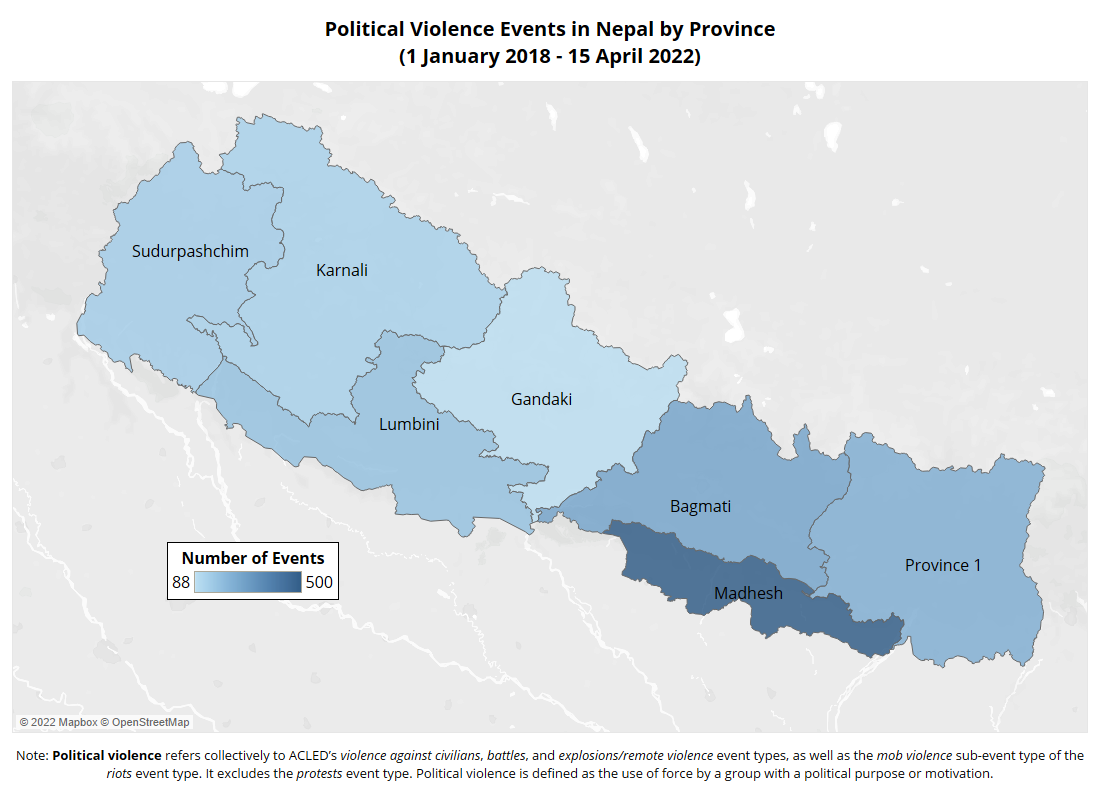

Subnational Trends: Political Disorder in Madhesh Province

Madhesh province, which borders India, has had the highest number of political violence events in Nepal for the past four years (see map below). In 2021 alone, 34% of all political violence recorded in Nepal was in Madhesh province. COVID-19 restrictions have led to mob violence in the region since the start of the pandemic, as people responded violently to restrictions preventing them from migrating across the border in search of work. Civilians have also been targeted by state forces for violating pandemic-related restrictions. Violence targeting women, Dalits, and ethnic and religious minorities is also more prevalent in the province than in other provinces in the country. Additionally, sporadic violence in the region can be traced to latent separatist sentiments, though demands for greater regional autonomy have predominantly found their expression in demonstrations as opposed to significant political violence in recent years.

COVID-19-Related Mob Violence

Since 2018, Madhesh province has had the highest number of mob violence events of all the seven provinces. Mob violence in the province reached a peak in 2020 as restrictions to prevent the spread of coronavirus were put into place. With all eight districts of Madhesh province bordering India, the province is home to some of the busiest India-Nepal border checkpoints. In a bid to curb the COVID-19 outbreak, the federal government of Nepal increased the deployment of security personnel along border regions (Shrestha, Fall/Winter 2020). During various lockdowns imposed over the last two years, the Nepal-India border has been closed, limiting cross-border movement. In 2020, following the onset of the pandemic, thousands of Nepali citizens, particularly migrant workers, were left stranded at the Nepal-India border after a border closure in March (Al Jazeera, 1 April 2020). In several instances throughout the year, Nepali and Indian citizens, including migrant workers, clashed with Nepali security personnel at the Nepal-India border in attempts to force their way into Nepal from India.

Violence Targeting Civilians

Madhesh province has also had the highest number of events of violence targeting civilians4Violence targeting civilians is defined by ACLED as inclusive of violence against civilians, explosions/remote violence, and riots events with interaction terms including 6 (peaceful, unarmed protesters) or 7 (unarmed civilians). The sub-event type excessive force against protesters is also included. in Nepal since 2018. Many of the violence targeting civilians events have been committed by state forces. These events have often stemmed from issues related to COVID-19. Following the onset of the pandemic in March 2020, police frequently assaulted locals, migrant workers, and farmers for failing to abide by the government’s stay-at- home order.

More broadly, state forces have also targeted women, with 36% of all reported events of political violence targeting women5For more on how ACLED defines political violence targeting women, see this FAQ document. by state forces since 2018 occuring in Madhesh province. Misconduct and excessive use of force have been a constant issue for the police in Nepal despite claims that they have instituted additional training to curb such behavior (Kathmandu Post, 3 June 2021). Human rights observers see impunity over previous misconduct and abuse by security forces committed during the civil war that ended in 2006 as a key contributing factor to the continuation of this activity (HRW, 18 October 2021).

Violent mobs have also perpetrated political violence targeting women, as well as Dalits and other ethnic and religious minorities. Political violence targeting women in Nepal can be seen in the targeting of women accused of engaging in witchcraft. Out of the seven provinces, nearly 46% of political violence targeting women over allegations of witchcraft6ACLED currently tracks a number of target identities related to political violence targeting women through the use of tags in the Notes column. Events in which women are targeted for their perceived practice of witchcraft include the tag: [women targeted: accused of witchcraft/sorcery]. was reported in Madhesh province since 2018. Vigilante mobs target women with allegations of witchcraft often in order to rationalize personal and communal hardships or misfortune such as illness or natural disasters. Vigilante violence targeting women accused of witchcraft is regarded as political as violent mobs take ‘justice’ into their own hands, challenging the state’s monopoly on the use of legitimate force, and vigilante mobs are thus viewed as agents of political violence. Nepal’s criminal code criminalizes allegations of witchcraft, with those found guilty of making allegations subject to up to five years in prison (Himalayan Times, 6 November 2017).

Madhesh province also accounts for over 40% of the total political violence events targeting Dalits and ethnic and religious minority groups since 2018. The majority of such events are incidents of mob violence. Persisting social beliefs in caste-based exclusion and ineffective implementation of laws banning caste discrimination have allowed these attacks to continue (United Nations, January 2020; Centre for Investigative Journalism-Nepal, 18 December 2020; Onlinekhabar, 25 May 2021). Elected representatives have reportedly been involved in perpetrating this violence, which has facilitated impunity as police are hesitant to register such cases, preferring to facilitate out-of-court settlements (Nagarik News, 16 September 2020).

Political Disorder Stemming from Demands for Greater Autonomy

Demands for greater autonomy have often driven political disorder in Madhesh province. The presence of armed groups in the Madhesh region dates back to the early 2000s when separate ‘liberation fronts’ were formed within the ranks of the Maoists to represent different ethnic minorities (Thapa & Ramsbotham, March 2017). This included the Madheshi National Liberation Front (MRMM), advocating for the Madheshi community (Thapa & Ramsbotham, March 2017). In 2004, the leader of the MRMM, Jai Krishna Goit, split from the Maoists following disagreements over guarantees for the autonomy of Madhesh province and the larger Terai region. Goit then formed the Democratic Terai Liberation Front (JTMM) which later became the Democratic Terai Liberation Front-Revolutionary (JTMM-K) (Himalayan Times, 14 March 2021).

Most Madhesh-based armed groups are now defunct, owing to a lack of political support, as well as the effectiveness of the federal government’s response (Thapa & Ramsbotham, March 2017). Some of these groups though, including the JTMM-K, have been involved in a small number of armed clashes and remote violence events in the past four years. Madhesh province has been the site of over 25% of armed clashes and over 16% of explosion/remote violence events in Nepal since 2018. Over a quarter of the 11 total armed clashes in Madhesh province involved Madhesh-based armed groups clashing with security forces. While most explosion/remote violence events remain unclaimed, nearly 15% of the events have been claimed by Madhesh-based armed groups, including the JTMM-K. The last recorded event involving such groups was on 14 March 2021, when the JTMM-K claimed responsibility for an explosion at the Land Revenue Office in Lahan of Siraha district that caused injuries to nine people; the government building was targeted over claims of corruption (Himalayan Times, 14 March 2021).

In recent years, the Madheshi community has largely held demonstrations to make political demands known, including calls for greater autonomy and revisions to citizenship laws. Demonstrations in the region are often held around the anniversary of the promulgation of the constitution of Nepal on 20 September. In 2015, deadly demonstrations erupted in southern Nepal in the final weeks leading up to and after the promulgation of the constitution, resulting in at least 45 deaths, including nine police officers (HRW, 16 October 2015). Madhesh-based political parties believe that several provisions of the constitution, including those relating to citizenship rights, representation, and federal state borders, do not meet the demands expressed during widespread demonstrations in the province in 2007, 2008, and 2015 (Dhakal, 29 July 2017).

In June 2020, Madhesh-based parties, led by the People’s Socialist Party, held widespread demonstrations demanding the withdrawal of a bill to amend the Citizenship Act. The bill would have granted foreign women married to Nepali men the right to apply for naturalized citizenship after residing in Nepal for seven years, while foreign men married to Nepali women would only be eligible after residing in Nepal for 15 years (Nepali Times, 19 December 2020). Madhesh-based parties opposed the bill, calling it discriminatory towards women in the Madheshi community. Moreover, the parties claimed that not allowing foreign women married to Nepali men to obtain naturalized citizenship immediately after marriage would jeopardize cultural and linguistic ties with India (Himalayan Times, 21 June 2020). Members of the Madheshi community have historical ties with neighboring regions of India, with cross-border marriages common.

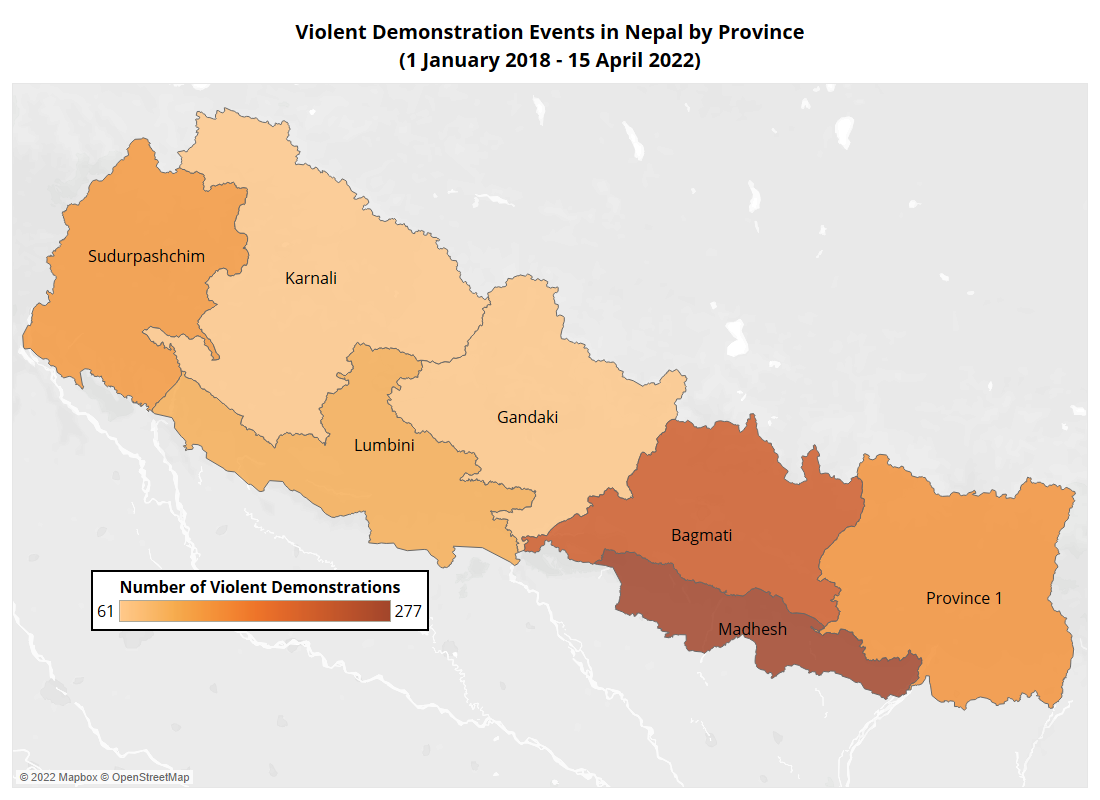

Groups in Madhesh province that advocate for greater autonomy, particularly newer political parties interested in influencing the political discourse, have turned to demonstrations to amplify the demands of locals. These demonstrations have sometimes been violent, making Madhesh province home to the highest number of violent demonstrations since 2018 (see map below). This trend has continued into 2022. This has largely been driven by the new regional Janamat Party’s demonstration campaigns in support of local farmers demanding better access to agricultural inputs such as irrigation and fertilizers. The Janamat Party, led by former secessionist leader CK Raut (Kathmandu Post, 8 March 2019), advocates for self-rule in Madhesh province and will be participating in the upcoming elections, further heightening political competition in local and provincial elections in the province.

Conclusion

This report has examined patterns of political violence and demonstrations in Nepal since 2018 when the first democratically elected government came to power under the 2015 constitution. Despite political competition that has sometimes led to violence, political views are largely — and increasingly — expressed through demonstration activity as seen in the increased number of demonstration events in 2021.

With elections scheduled throughout 2022, though, certain political violence risks remain elevated. Notably, the percentage of events of inter-party and intra-party political violence relative to overall political violence has increased as parties and party factions compete for power. Moreover, lingering issues concerning greater autonomy for Madhesh persist, contributing to the concentration of political disorder in the province. It remains to be seen how the outcome of the elections will impact disorder trends in Madhesh province and all of Nepal.