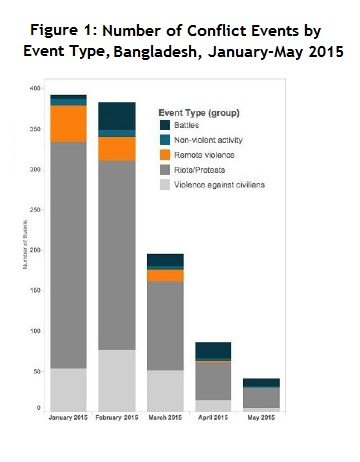

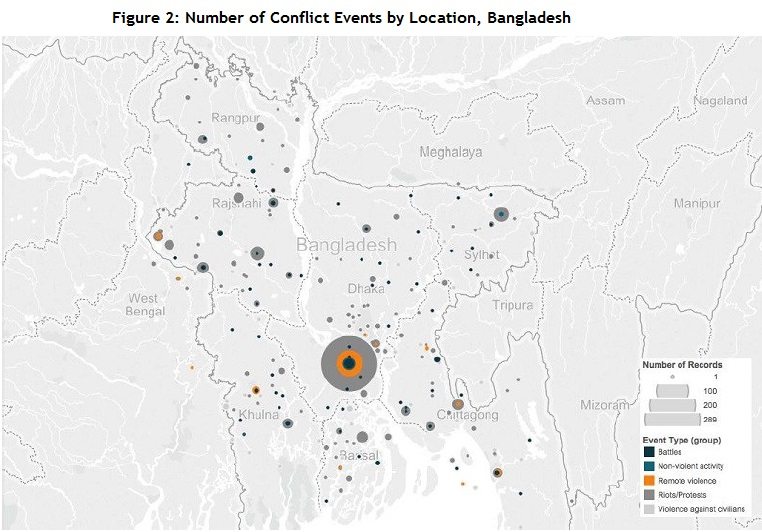

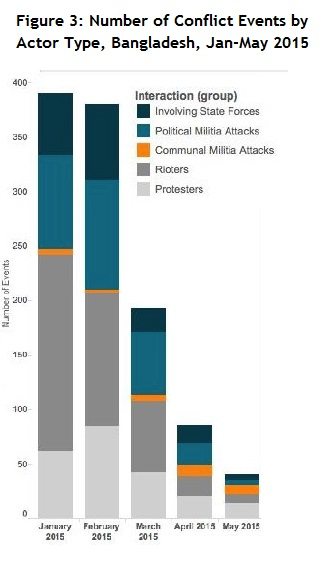

Bangladesh has been in political turmoil since early January, leaving more than 150 people dead and thousands injured. Confrontational politics are not new in Bangladesh, but they have intensified in the recent months, reaching its highest level in late January and the beginning of February. Two thirds of activity included vandalism, crude bombs, clashes between political opponents, rioters and the police, and high numbers of arrests. While violence against civilians escalated, political turbulence allowed religious and extremist militants to take advantage of the unstable political situation. The roots of this spike in violence are in the historic rivalries between two political parties – the ruling secular, socialist Awami League (AL) and its opposition, the Bangladesh National Party (BNP) with its Islamic orientation.

Marking the one-year anniversary of Bangladesh’s contested elections on 5 January, the opposition Bangladesh National Party (BNP), declared a transportation shutdown and general hartal (strike) to force the government to resign and elections to take place. The ruling Awami League’s (AL) decision two days earlier to confine BNP leader, Khaleda Zia (former prime minister), to her party’s headquarters in Dhaka, triggered violent clashes between AL and BNP activists. Opposition protests were accompanied by a rise in militia activity, including the launching of a series of petrol bomb attacks against passengers travelling in buses and other vehicles, particularly trucks. About 200 people have been killed from burn injuries and thousands injured. The AL government responded to the opposition’s countrywide demonstrations with a tough crackdown on protesters, including widespread detentions by the police. Media reports indicated that as many as 7,000 opposition activists were arrested by the police.

Mayoral elections were scheduled for late April in Dhaka and Chittagong, in which the BNP decided to participate, in an effort to resolve the political confrontation. In the days leading up to the elections, militants attacked Zia’s electoral motorcade three times, leaving her bodyguards and several other people injured in bullet attacks. The elections themselves were largely peaceful, but ultimately boycotted by BNP because of vote rigging (IDSA, 01.05.2015).

Enmity between the two major parties have marked Bangladesh’s history since its independence in 1971 and revolve around ideological fault lines, such as questions of secularism, Bengali nationalism and the role of Islam (ICG, 2015). In December 2008, AL leader Sheikh Hasina won the elections, putting an end to a two-year military-backed caretaker government. Hasina’s government, however, was marked by a high level of corruption, partisan bureaucracy and a worsening human rights record (ICG, 2012). The last general elections on 5 January 2014, the most violent in its history, were boycotted by the opposition BNP and its ally JeI, leaving the ruling AL to win the majority of seats.

Personal enmity between the two female leaders is as important for the understanding of the crisis as the ideological differences between the two parties. Both Zia and Hasina have lost close relatives in attacks – Hasina her father,the founder of Bangladesh Mujib ur Rehman, and Zia, her husband, former president Ziaur Rahman. Both hold the other side accountable for the murders. For many supporters personal loyalties are more important than ideological accordance.

The recent turmoil has clearly shown that residual capacities of subversive and extremist elements, including JeI (declared illegal by AL in 2013), and its student wing- Islami Chhatra Sibir (ICS)- are still significant, and their alliance with BNP remains strong. Both JeI and ICS have shown their propensity for violence in recent attacks, and are believed to have links to extremist jihadi groups. Further, surviving fragments of a range of other extremist outfits, including Jamaatul-Muslimeen (JMB) and Ansarullah Bangla Team (ABT), became more active in the last months (SATP). Particularly alarming was the killing of three liberal bloggers, Avijit Roy, Washiqur Rahman and Ananta Bijoy Das, attributed to Islamic militants opposed to the victims’ secular views, including a ‘sleeper cell’ of Islamic militant ATB (The Financial Express, 02.04.2015). Human Rights advocates have also voiced their fear that the often lawless responses of police forces to violent protests is providing an opportunity to militant groups to attract new recruits from opposition supporters. In addition, Bangladesh’s troubled situation led to a lack of governmental control in rural areas, which experienced an increased number of land grabbing incidents and violent clashes of communal groups of the establishment of supremacy in rural areas.

Amidst violence and hartals, the majority of Bangladeshis continued with their routine, often taking on the risk of being attacked by hartal enforcers while proceeding to work. Relying on daily wages, the majority of Bangladeshis cannot afford to stay at home. Political turmoil has already caused economic losses of around $2.2 billion (1 percent of GDP), according to the World Bank. The garment industry, which makes up 75 percent of the country’s exports and provides employment for a large number of Bangladeshis, is particularly affected as delivery schedules are disrupted and garment buyers have started to shift their orders to other countries.

Political deadlock between the ruling AL and opposition BNP has recurred since the country’s independence, but the latest wave of violence is unprecedented. Three months of turmoil have severely affected Bangladesh’s economy and provided space for Islamist militants. Though violence has slowly come to an end, confrontational politics will continue to dominate the political agenda, leaving Bangladesh on the edge of instability.

AnalysisAsiaCivilians At RiskLocal-Level ViolencePolitical StabilityRemote ViolenceRioting And ProtestsViolence Against Civilians