The ruling Trinamool Congress Party (TMC) secured a comfortable victory in the 2018 West Bengal panchayat (village government) elections on May 14 in India. However, political violence and inadequate security arrangements during the election nomination and polling phases prevented opposition parties and citizens from fulfilling their democratic right to participate in free elections.

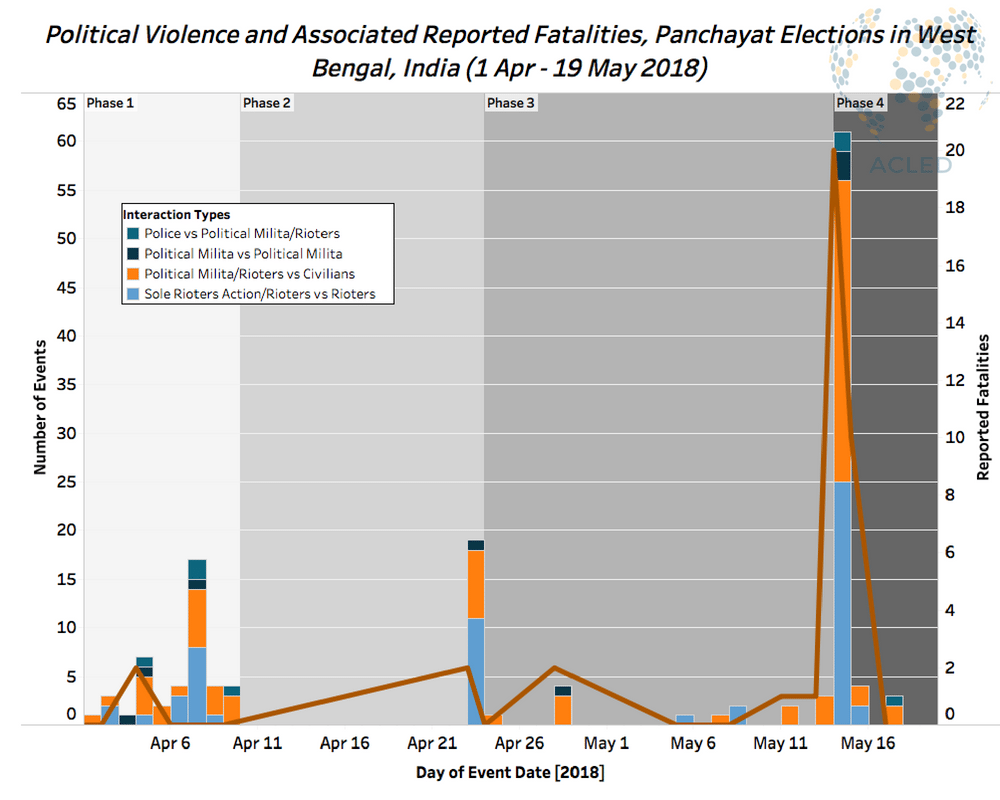

The different phases of the election were marred by significant levels of violence. During the initial phase of the filing of nomination papers (due on April 9), reported violence and associated fatalities were considerably higher than weeks prior (over 10 times as many events reported and twice as many reported fatalities, relative to the week prior. Violence and intimidation attempts made against supporters of opposition parties led to an extension of the deadline to April 23 (Hindustan Times, 26 April 2018); this second phase too was marred by violence and riots following a week without any reports of violence. This was followed by a third, relatively less violent phase before the final phase which included both the election on May 14 as well as the re-polling on May 16; both the number of reported events and fatalities spiked during this phase. As the graph below shows, most of these instances of violence were attacks on civilians [in orange] (ranging from minor assaults to murder); followed by rioting, both one-sided and between supporters of political parties [in blue], and armed battles between party workers [in navy]. Despite high levels of violence, police intervention was only reported in 4% of events [in teal], demonstrating a stark underemployment of the state security apparatus.

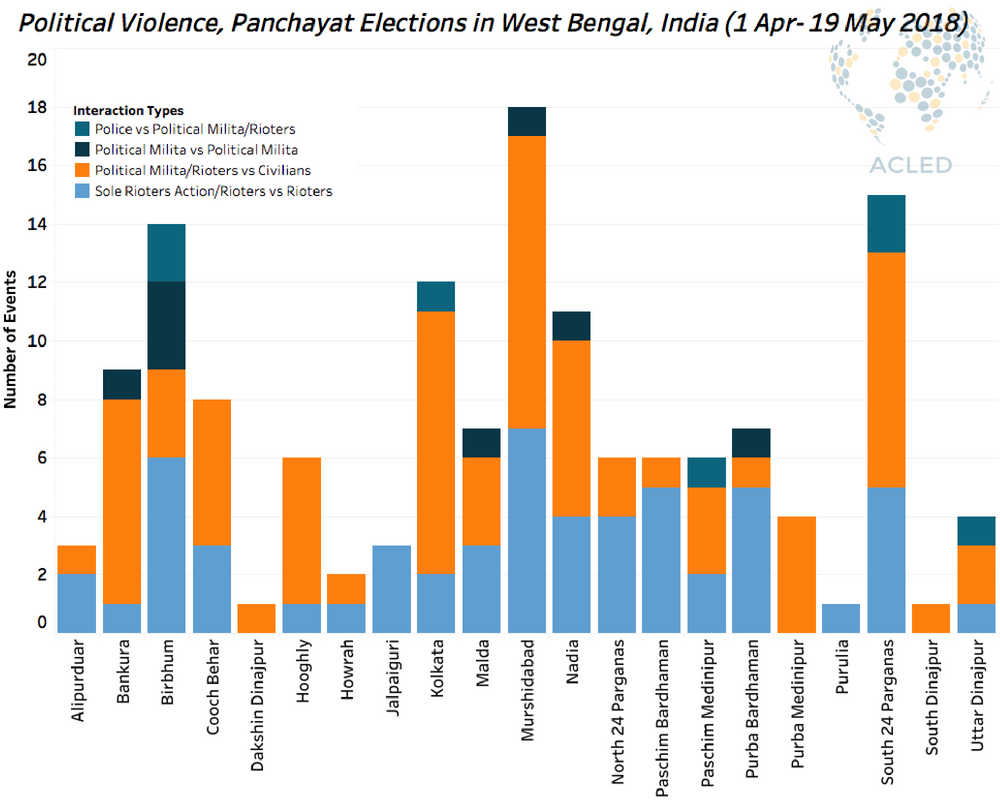

The political violence seemingly benefitted the ruling TMC party as opposition parties failed to register a candidate in over 34% of seats across all districts. This led to the TMC securing one-third of the seats available in West Bengal’s three-tier panchayat election uncontested (The Hindu, 1 May 2018). The highest proportion of uncontested seats were reported in Murshidabad, South 24 Parganas, Hooghly, Bankura, Purba Bardhaman, Paschim Bardhaman and Birbhum districts (The Hindu, 1 May 2018). As the graph below depicts, over half of election-related violence during this time took place in those districts.

The state of West Bengal has a long history of election violence. While the latest panchayat election may not have been the deadliest recorded election, the levels of violence continue to stand out in comparison to local body elections in other states across India. This is a clear indicator that — even after the regime change in West Bengal’s state government in 2011– the now ruling TMC party continues to use violence paired with insufficient security arrangements as a means to combat opposition and secure electoral victory (Business Standard, 30 April 2016).