On October 7, 2001, the United States (US), supported by the United Kingdom, invaded Afghanistan with the stated aims of dismantling al-Qaeda and denying it a safe haven by overthrowing the Taliban government in Kabul (ABC News, August 21, 2017). After the fall of the Taliban government, the force was formalized into the NATO-led International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) in December 2001 by the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) in Resolution 1386. The ISAF was composed of a coalition of 40 countries, which included all NATO members and a number of non-NATO partner nations such as Australia, although with US soldiers generally accounting for close to half of the total troop contributions at minimum (NATO, May 23, 2017).

After almost 14 years of operations, the ISAF formally ended its combat mission on December 28, 2014 (Washington Post, December 28, 2014). This was followed by the start of Operation Resolute Support, a second NATO-led mission authorized by the UNSC under Resolution 2189, on January 1, 2015. Operation Resolute Support was devised as a “train, advise, and assist” mission, with its primary focus being the continued provision of training and support to the Afghan security forces to assist in their conflict against insurgent groups in the country (NATO, 2018), most notably the Taliban and the Islamic State (IS). However, although Operation Resolute Support was meant to lay the groundwork for an eventual exit of NATO forces from Afghanistan, by June 2016 US forces had been reauthorized to directly support Afghan offensive operations, particularly through the use of close air support (CNN, June 10, 2016).

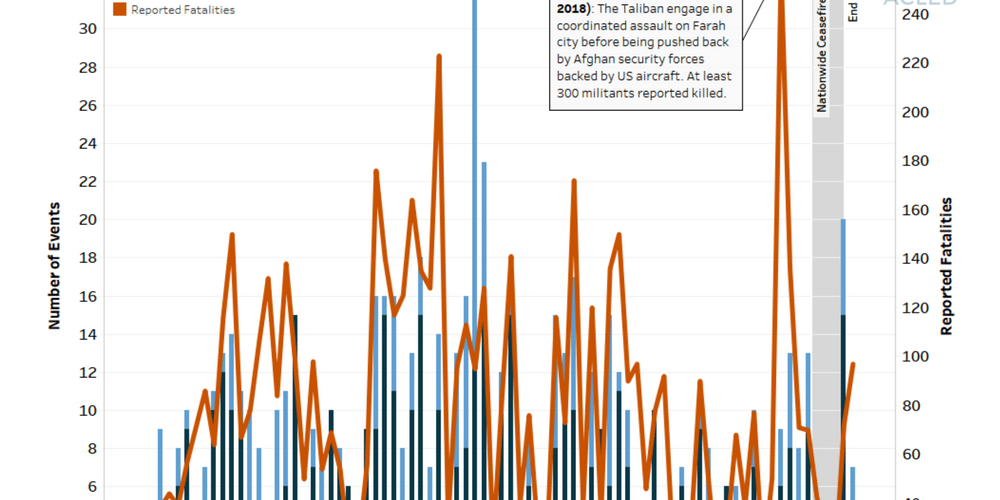

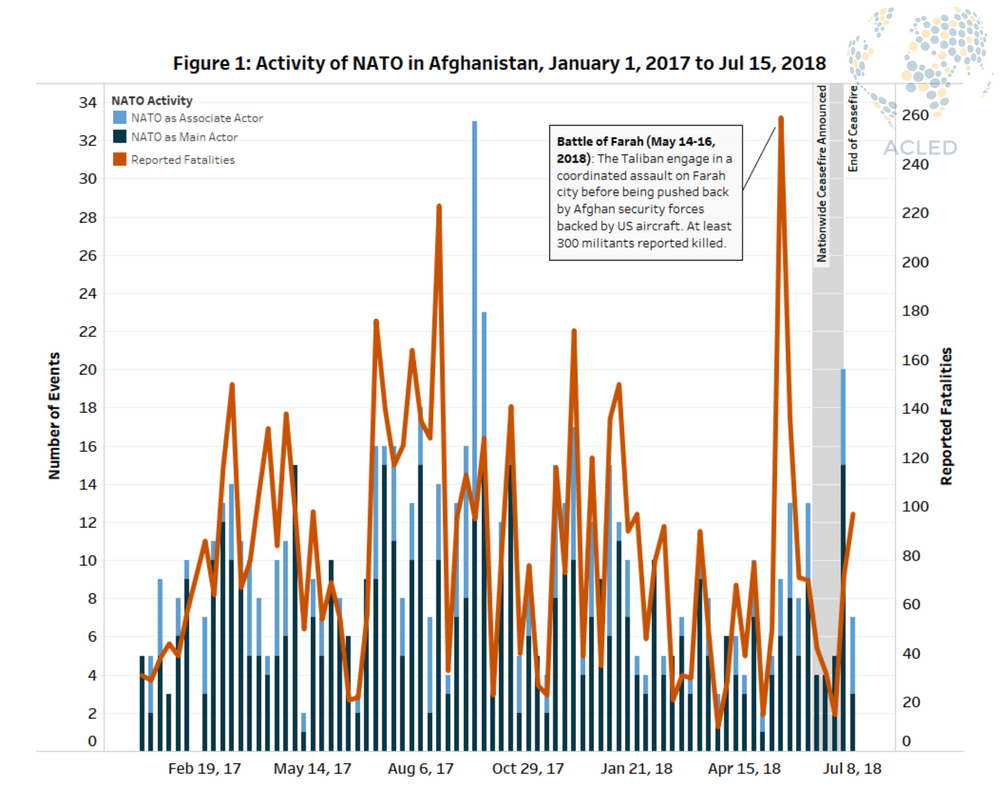

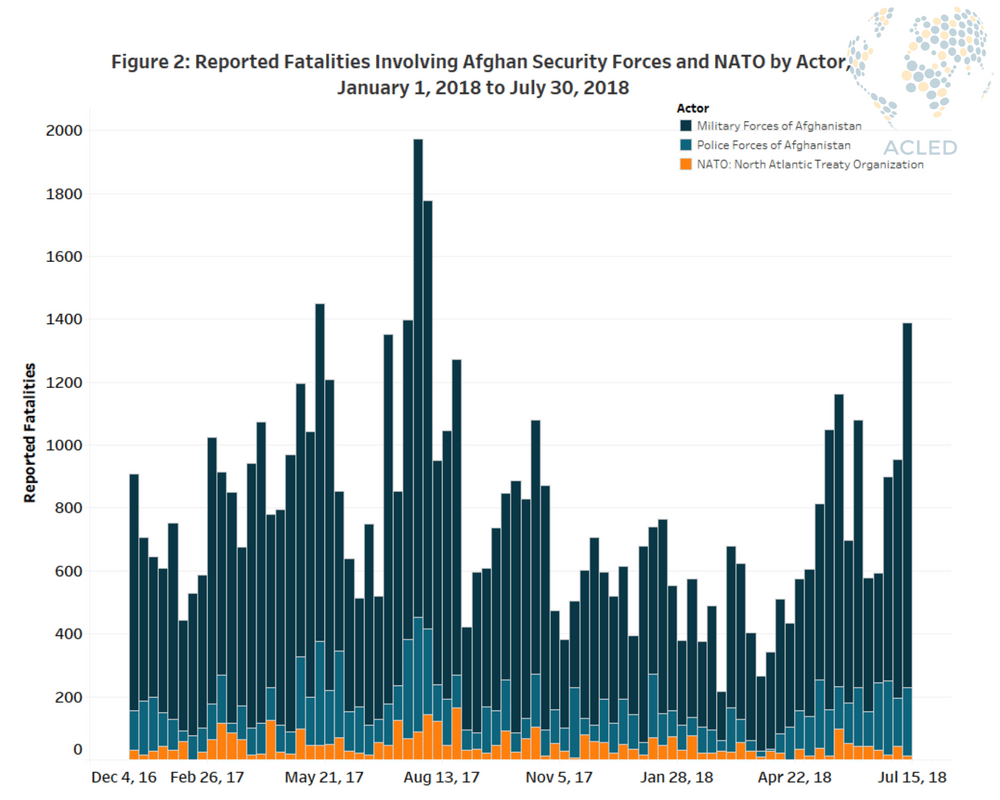

Since then, ACLED data show that NATO forces, which are largely synonymous with American forces when it comes to combat situations, have continued to engage in regular operations throughout 2017 and the first half of 2018, primarily in support of Afghan forces (see Figure 1). However, the absolute number of events involving NATO forces is quite low relative to the overall level of activity of the Afghan security forces. This is reflected most clearly in the number of reported fatalities associated with events involving NATO forces relative to Afghan security forces. Despite often resulting in over 100 reported fatalities per week in 2017 before dropping in 2018, these numbers are dwarfed by the number of reported fatalities each week involving security forces (see Figure 2). Overall, this suggests that the core objective of the mission–training Afghan security forces–is showing positive results as the Afghan military and police are increasingly confident operating independently of NATO forces.

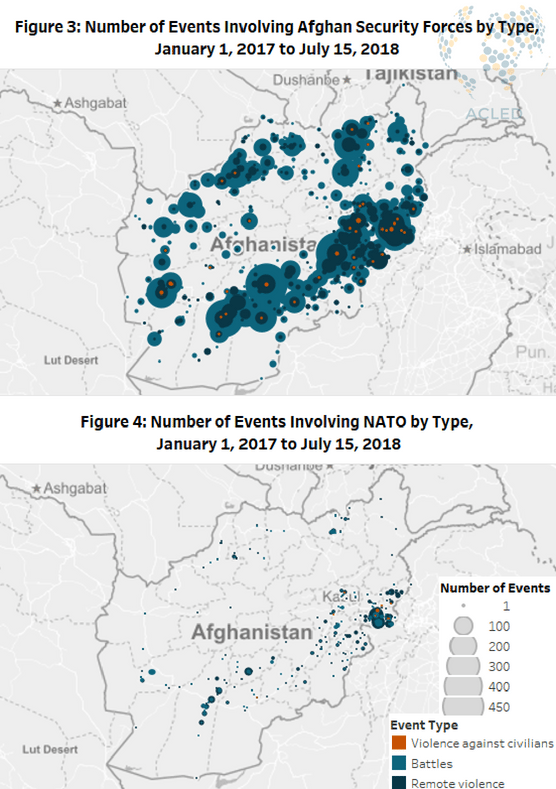

This can be further illustrated by examining the geographic distribution of NATO activity across Afghanistan. While Afghan security forces are engaged in regular activity across all 34 of the country’s provinces (see Figure 3), NATO activity is largely clustered in a small number of border provinces (see Figure 4). These include Nangarhar, Kunar, and Helmand on the borders of Pakistan, as well as Farah and Kunduz, which border Iran and Tajikistan, respectively. This distribution broadly reflects the “hub and spokes” approach of Operation Resolute Support, with the hub in Kabul, and the spokes in Herat, Mazar-e-Sharif, Kandahar, and Laghman, which all neighbour the provinces where most NATO activity takes place (NATO, July 2018).

In terms of attribution, events involving NATO forces were overwhelmingly reported as involving American forces, while a significant minority remained attributed only to unspecified “foreign” or “international” forces. Out of the 744 total events of political violence involving NATO that ACLED has recorded in Afghanistan, 432 had specific reports of American involvement, while only 12 involved other NATO or broader coalition members. Of these 12 events involving non-American NATO troops, almost all were attacks targeting either NATO convoys or bases, while none included offensive combat operations.

In terms of NATO’s combat operations, these events were largely composed of remote violence in support of Afghan security forces. One example of this type of support was during the Battle for Farah, which lasted between May 14 and May 16, 2018 (see Figure 1). This battle involved a Taliban assault on Farah city, the provincial capital, which initially succeeded in over-running parts of the city before Afghan reinforcements could arrive (New York Times, May 15, 2018). Backed by US air support, Afghan security forces were able to re-establish control over the town, with the resulting clashes leaving at least 300 militants dead (Al Jazeera, May 16, 2018).

But as the Farah attack suggests, while NATO activity in Afghanistan has decreased slightly in the first six months of 2018 compared to last year, this does not necessarily reflect a positive evolution in Afghanistan’s conflict. Events involving the Afghan security forces are rising again after a lull during the winter months of 2018 and a drop during the unilateral ceasefire called by President Ashraf Ghani against the Taliban for much of June 2018 to entice the Taliban to the negotiating table (Al Jazeera, June 17, 2018). Although the Taliban reciprocated with a 3-day ceasefire over the Eid holiday period that was reportedly adhered to, the government’s eventual abandonment of the ceasefire despite a 10-day extension into late June (CNN, June 30, 2018), has resulted in an upsurge of both reported fatalities and events of political violence across the country.

Within this context, it seems likely that increased conflict will lead to a consequent increase in NATO operations in support of Afghan security forces, as was the case immediately after the end of the ceasefire (see Figure 1). This outcome is further supported by the pledges by NATO member states at the recent Brussels summit to continue funding Operation Resolute Support through 2024 and by 29 members to increase their individual military or financial commitments to the mission (US Army, July 24, 2018). This is notable as the US currently contributes more than half of all troops involved in the mission, with Operation Resolute Support being composed of 8,475 US troops out of a total 16,229 as of July 2018 (NATO, July 2018).

Despite signals that NATO members expect to be in Afghanistan for the long haul however, hopes for a more positive outcome remain. Both the commanders of Operation Resolute Support, General John Nicholson, and of US Central Command (CENTCOM), General Joseph Votel, have expressed support for an Afghan-led peace process and negotiations with the Taliban in the aftermath of the ceasefire (Khamaa Press, July 24, 2018). This note of cautious optimism is also in line with an increase in the optimism (albeit slightly) among Afghans in the direction of their country in 2017, as reported by the Asia Foundation’s annual “A Survey of the Afghan People”, after almost a decade of increasing pessimism (Asia Foundation, 2017). In any case, it remains to be seen whether the success of the Eid ceasefire represents a real desire by the mainstream Taliban factions to enter into peace negotiations, or if it will be necessary for NATO to continue supporting the Afghan security forces through 2024 and beyond.

Find an explanation of ACLED’s methodology for monitoring the conflict in Afghanistan here.

This piece is part of a special series with a focus on coalitions in the Middle East. For more information about the series, please refer to Special Focus on Coalition Forces in the Middle East.