On July 25, 2018, Pakistan held its first general election in five years. With the 2013 election described as one of the “bloodiest” in Pakistan’s history (BBC News, May 2, 2013), the 2018 election seems to have followed the trend following high-casualty attacks carried out by the Islamic State and a number of reports of violence at polling stations on election day. However, despite the perception this violence has engendered, Pakistan is in a very different place now than it was during its 2013 general election. Since then Pakistan has engaged in two major, successful military operations, Operation Zarb-e-Azb and Operation Radd-ul-Fasaad, which together have contributed to a dramatic decrease in the number of both events of political violence and reported fatalities across the country. This helps to explain why, relative to the 2013 election, the 2018 election was characterized by both fewer political violence events and reported fatalities from election-related events.

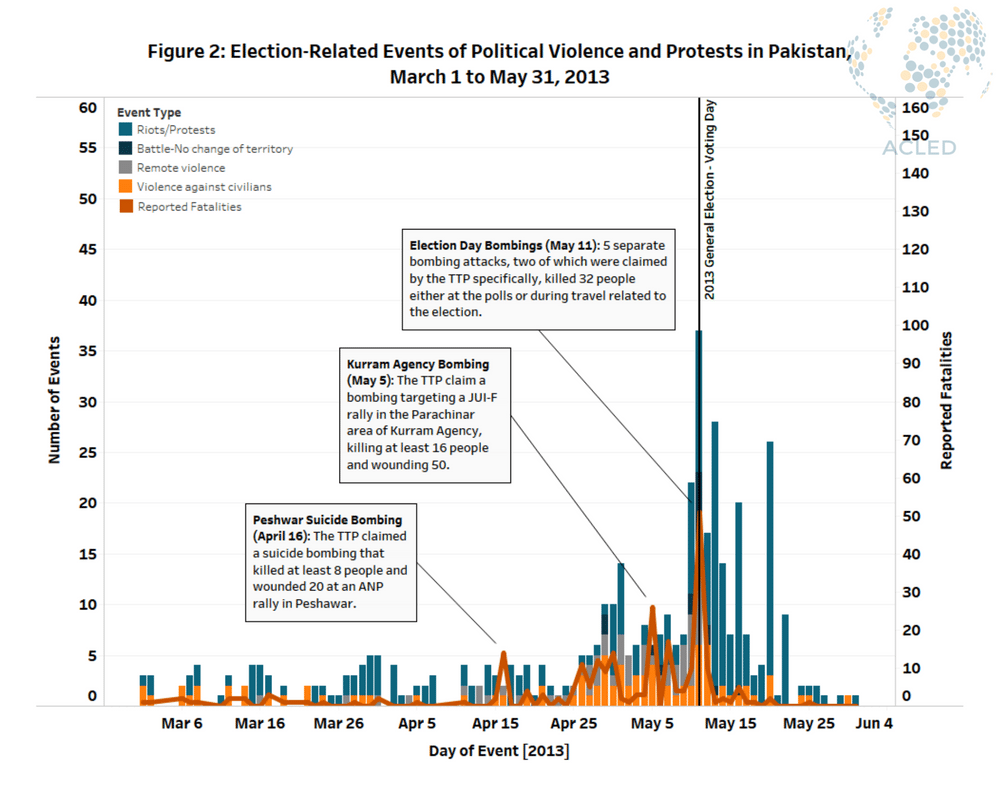

In May 2013, the Pakistani government was in the midst of an intense conflict with the Tehreek-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP). In the run-up to the 2013 general election, the TTP had warned people to stay away from the polls and identified three parties in particular, the Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP), Muttahida Quami Movement (MQM), and Awami National Party (ANP), for targeting. During the month leading up to the election, almost daily attacks were reported on election rallies and candidates. On election day itself (May 11, 2013), at least 33 people were reportedly killed in various bombings, while another 18 were killed in clashes between supporters of various candidates or unclaimed gun attacks. In the end, more than 240 fatalities were reported in election-related events, resulting in the 2013 election being given the macabre moniker of “bloodiest” in Pakistan’s history (BBC News, May 2, 2013).

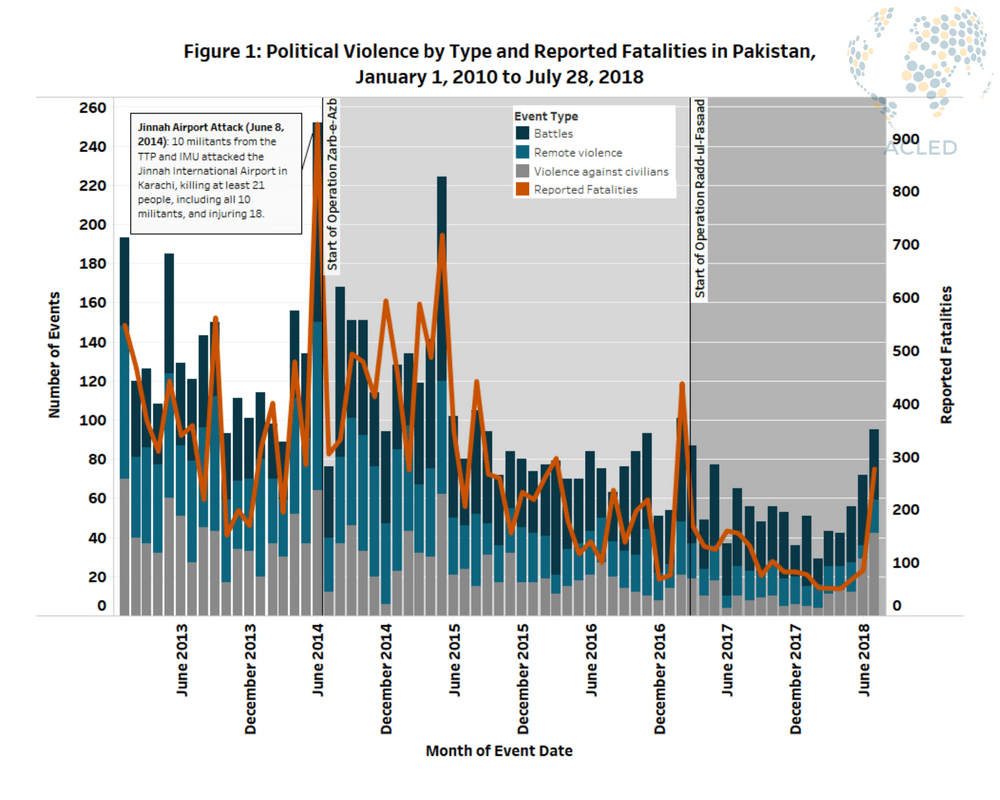

Since the 2013 election, significant progress has been made by the Pakistani government in rolling back the serious threat posed by militancy to the country’s political process. The turning point came after the joint-TTP/Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU) attack on Karachi’s Jinnah International Airport in Karachi on June 8, 2014. This attack motivated the Pakistani government to authorize a major operation to combat not just the TTP and IMU, but all militant groups across the country. This began with an initial focus on clearing militant strongholds in North Waziristan before expanding across much of the north and west of the country, and into Pakistan’s largest city, Karachi. Zarb-e-Azb lasted from June 15, 2014 to April 3, 2016, with a further clearance phase continuing until February 22, 2017. In terms of achieving its stated aims of diminishing militancy across the country, the operation seems to have been a success, as ACLED recorded a significant decrease in the number of reported fatalities and political violence events since May 2015 (see Figure 1), despite notable spikes in August 2015, March 2016, and February 2017 (see this ACLED article for more information on Operation Zarb-e-Azb).

Following the end of the Operation, a new effort, Operation Radd-ul-Fasaad, began with the aim to “disarm and eliminate the hidden terrorist sleeper cells across the country” and “consolidate the gains of Operation Zarb-e-Azb” (Dawn, February 22, 2017). Despite the success of Zarb-e-Azb, a new wave of militant attacks in February 2017, the most significant of which was the Sehwan Shrine bombing (Washington Post, February 16, 2017), convinced the government that further action was necessary, this time with a greater focus on Pakistan’s urban centres and Punjab province. Operation Radd-ul-Fasaad was the result, and seems to have achieved significant success during its ongoing activities (The Express Tribune, April 17, 2017). Since the start of Operation Radd-ul-Fasaad, reported fatalities and political violence events in Pakistan have dropped to the lowest levels recorded.

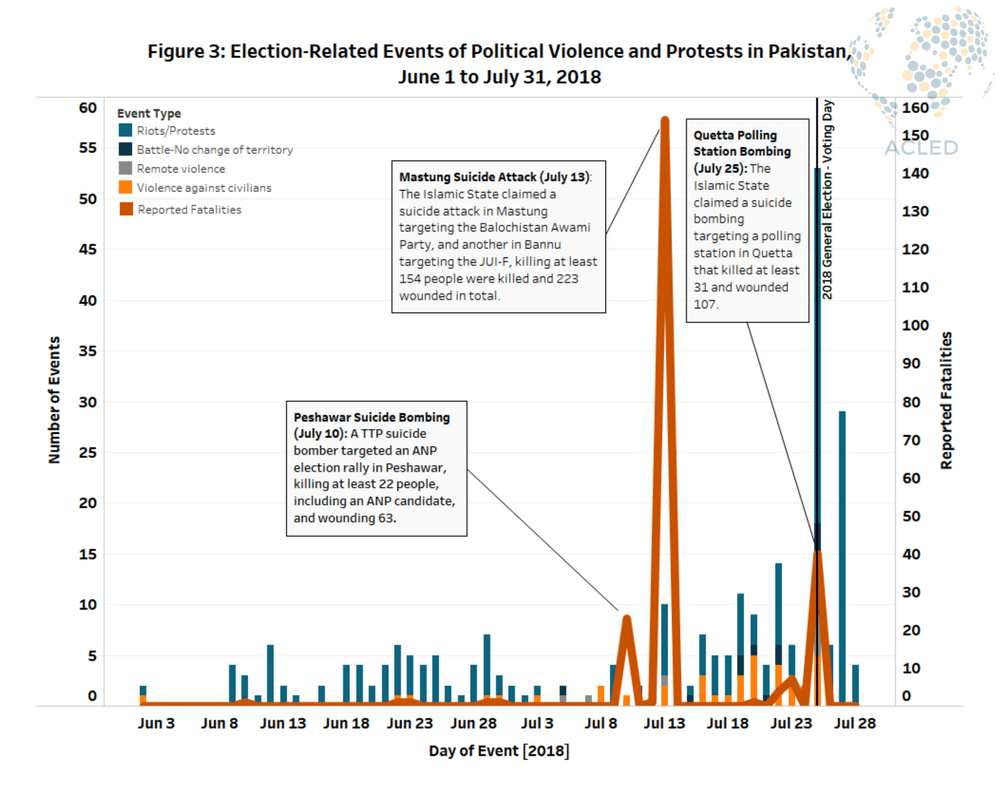

Looking to the 2018 election cycle, it is apparent that Pakistan’s conflict environment in 2018 is far removed from the one that existed in 2013. With the operational capacity of many militant groups strongly curtailed, as reflected in the diminished number of reported fatalities and political violence events throughout the country, Pakistanis went into the 2018 election period enjoying greater security than in 2013. In terms of the number of events, ACLED recorded more than 210 events of election-related political violence in 2013, compared to 145 in 2018. In terms of reported fatalities, the difference is much less pronounced at 247 fatalities during the 2013 election, compared to 235 during the 2018 election. But to properly illustrate the full extent of the difference between these two elections, it is necessary to break these numbers down a bit.

One of the most salient difference between the 2013 and 2018 elections was the relative number of events reported involving militant groups. In 2013, the TTP was the primary threat to the political process based on the number of reported fatalities and political violence events, while by 2018 the Islamic State had taken over this role, yet engaged in far fewer, albeit more lethal, attacks. As such, the relative involvement of TTP and IS in the two elections offers one of the most extreme contrasts between Pakistan in 2013 versus 2018. Out of the 176 events of election-related political violence in 2013 (see Figure 2), the TTP was reportedly responsible for 46, compared to the Islamic State’s reported involvement in only 3 such events in 2018 (and the TTP’s own involvement in only a single election-related event). This is a significant difference in activity by these two groups, and offers potential insight into the diminished operational capacity among militant groups in Pakistan in 2018 compared to 2013.

That being said, the events that IS was involved in during the 2018 election were far more lethal than those that the TTP carried out in 2013. The suicide attacks in Mastung and Bannu on June 13, 2018 reportedly killed a total of 154 people and injured at least 223. Meanwhile, a suicide bombing targeting a polling station in Quetta on election day (July 25, 2018) reportedly killed 31 people and wounded at least 70. This means that the Islamic State was responsible for just under 80% of all reported fatalities in the 2018 election period (see Figure 3), whereas the TTP was responsible for less than 50% of the 247 fatalities during the 2013 election period despite being involved in 46 events. This contrast shows that despite IS being far less active in terms of involvement in events, their attacks, particularly on soft targets such as election rallies, can have a significant impact and drive home the continued threat that militancy poses for the political process in Pakistan.

On the other hand, much of the political violence in both of these elections was also carried out by groups within the political process. In 2013, out of the 210 reported events of political violence (including remote violence, battles, violence against civilians, and riots), only about 20% of these involved political parties participating in the election, compared to almost 50% in 2018. This increase in the proportion of violence being carried out by groups within the political process may represent increasing competition among parties within the framework of elections, or a growing level of violent bipartisanship. The latter may in fact be more accurate, as the two most well-established parties — the incumbent Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (PML-N) and their rival the PPP — were beaten by a relative newcomer, the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI), led by former cricketer Imran Khan. This seems to signal serious frustration among Pakistan’s population with the established political parties and political figures, given the significant increase in the PTI’s share of the vote compared to 2013 (The Economic Times, July 28, 2018). This is also supported by the anti-corruption focus of the PTI’s largely populist platform (The Guardian, July 27, 2018), which follows the broader trend seen around the world of populist leaders railing against corruption, in countries as diverse as the United States, Turkey, and the Philippines.

As Pakistani politics have changed between 2013 and 2018, so have the dynamics driving politically-motivated conflict. What is clear from this election cycle is that while the TTP’s operational capacity seems to have been significantly curtailed since 2013, significant challenges still appeared during the 2018 election both from inside and outside of the political process. The main problem going forward will be how to deal with those groups outside of the political process, most notably the Islamic State, which although engaging in fewer attacks than the TTP did in 2013, have dramatically illustrated that they remain a threat to the Pakistani people and their political processes. This will need to be tackled in tandem with the threat that increased inter-party violence presents to the democratic process. Otherwise Pakistan’s elections will continue to be shadowed by the spectre of violence which has become their unfortunate hallmark.

AnalysisAsiaCivilians At RiskCurrent HotspotsElectionsPolitical StabilityRemote ViolenceRioting And ProtestsViolence Against Civilians