In the final days of August in Libya, fierce fighting erupted in Tripoli between the partnering 7th Brigade and a coalition of militias comprised of the Tripoli Revolutionaries Brigade, Bab Tajoura Brigade, Ghanewa Brigade, Nawasi Brigade and Misrata’s 301 brigade (Libya Observer, 31 August 2018). The invasion by the 7th Brigade took the Tripoli-based militias by surprise. The Government of National Accord’s (GNA) response reportedly included airstrikes on Tarhouna where the 7th Brigade is based, which is believed to have prompted protests against the GNA — itself still struggling to staunch the 7th Brigade’s advances. The potential for new militias (whether newly formed, formerly moribund, or defecting from government-affiliated forces) to mobilize and attempt to extend their influence to Tripoli represents a grave threat to the stability of the city and to Libya generally; given the number and characteristics of newly active militias, it is likely that the security landscape will continue to fragment as the year progresses.

Since launching the attack on Tripoli, the 7th Brigade appears to have brokered an alliance with the Sumood Brigade and is seeking to expand its influence to Tripoli (Libya Observer, 1 September 2018). The GNA has declared a State of Emergency in Tripoli — though it remains unclear what such a designation implies, and the GNA’s ability to impose any security agenda has been called into serious question (Al Jazeera, 2 September 2018).

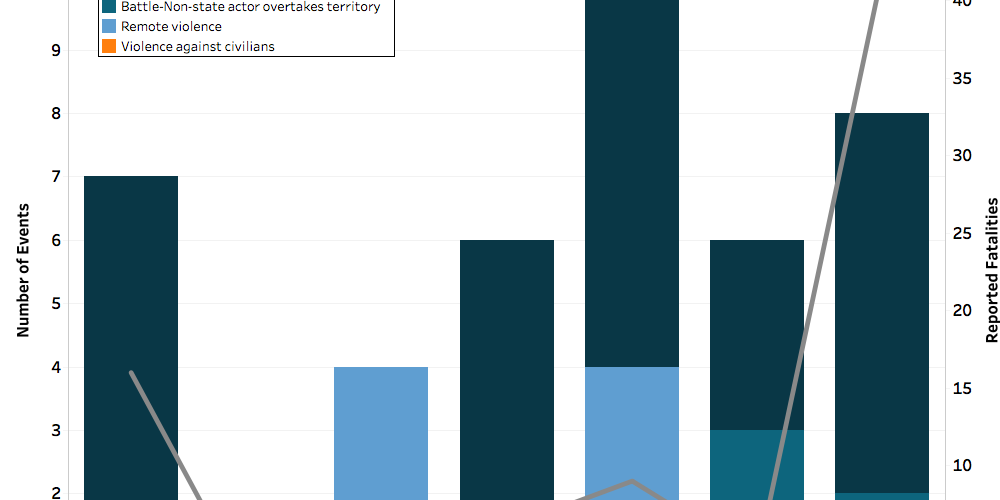

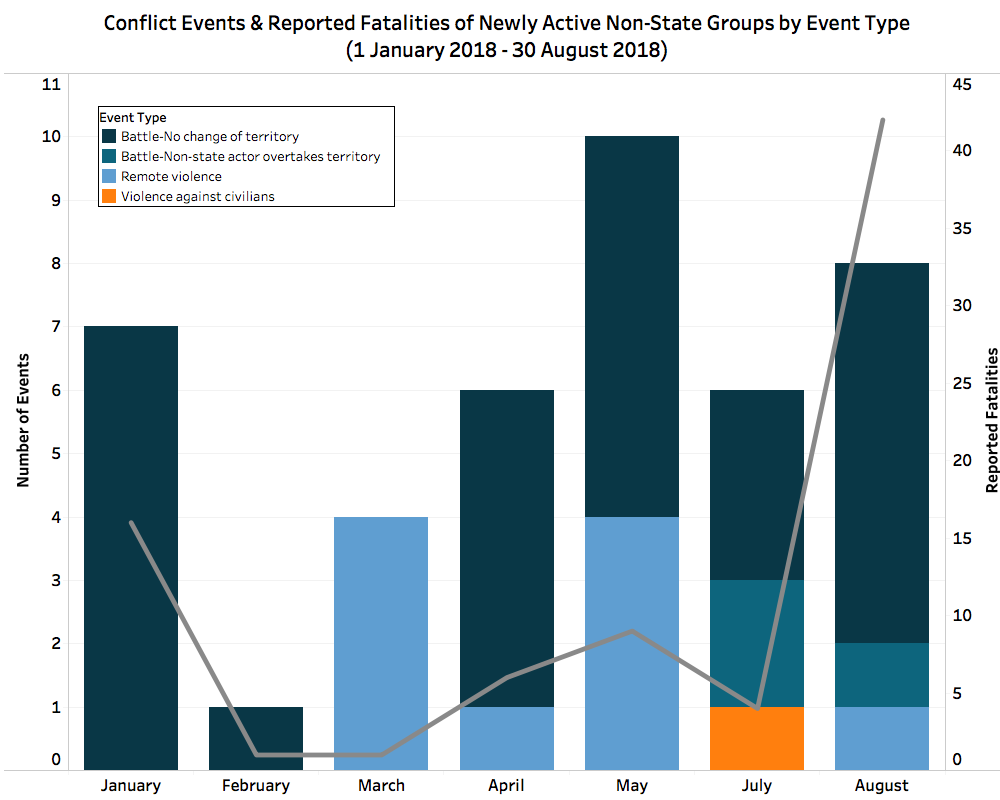

Seventeen named militias that were not active in 2017 have been associated with violence in Libya since the start of 2018 — a tally that includes the 7th Brigade. If other newly emergent or revived groups attempt to follow in the footsteps of the 7th Brigade, both Tripoli and the host communities from which these militias emerged could be further destabilized by new militia activity. As demonstrated in the graph below, these new groups appear to be launching more attacks as 2018 progresses, with a significant uptick in the number of reported fatalities associated with these groups as well.

The events of last week (August 26 through September 1) resulted in 39 reported fatalities and dozens more injuries. The pervasive insecurity forced the closing of the airport on August 31. Some reports emerged on the 31st that a truce, “the third one in just four days,” had been reached to bring the conflict to a halt — though it quickly became clear that the agreement would not hold (Libya Observer, 1 September 2018). The 7th Brigade, lead by Muhsen Al-Kani, rejected the truce, asserting its intention to “cleanse Tripoli of corrupt militias … who use their influence to get bank credits worth millions of dollars while ordinary people sleep outside banks to get a few dinars” (Al Jazeera, 3 September 2018). Heavy fighting between the militias and shelling of communities in southern Tripoli were again reported on September 1.

Throughout the siege, the 7th Brigade attacks targeted militias at least nominally affiliated with the GNA, including the Ministry of Interior-linked Tripoli Revolutionaries Battalion. This is a notable change in the group’s mandate given that the 7th Brigade was reportedly established by the GNA’s Defense Ministry in 2017 (Human Rights Watch, 1 September 2018); following the recent clashes, the head of the Presidential Guard released a statement denying any involvement with the 7th Brigade (Libya Observer, 28 August 2018), while other accounts report that the 7th Brigade is considered “an outlawed group” by the GNA (Asharq Al-Awast, 4 September 2018). Though the history surrounding the 7th Brigade is murky, its turn against the GNA suggests that the government’s uneasy relationships with other deputized militias may evolve into additional threats to the GNA’s fragile hold on power. If other GNA-affiliated militias defect from their relationship with the government or engage in in-fighting, the consequences for Libyan security would be dire.

A number of the newly active groups identified by ACLED share a similar background to the 7th Brigade, including the 6th Infantry Brigade (which claimed in February 2018 to be aligned with the GNA [Libya Herald, 22 February 2018]) and the Ghaniwa Brigade (which is associated with the Ministry of Interior, yet engaged in fighting with another Ministry of Interior-affiliated militia in April [Libya Observer, 30 April 2018]).

Also depicted in the graph above regarding the activities of the newly active non-state groups is that these groups engage in remote violence, while direct violence targeting civilians specifically is more limited. Since mid-July, the reported fatalities associated with these groups has been sharply rising.

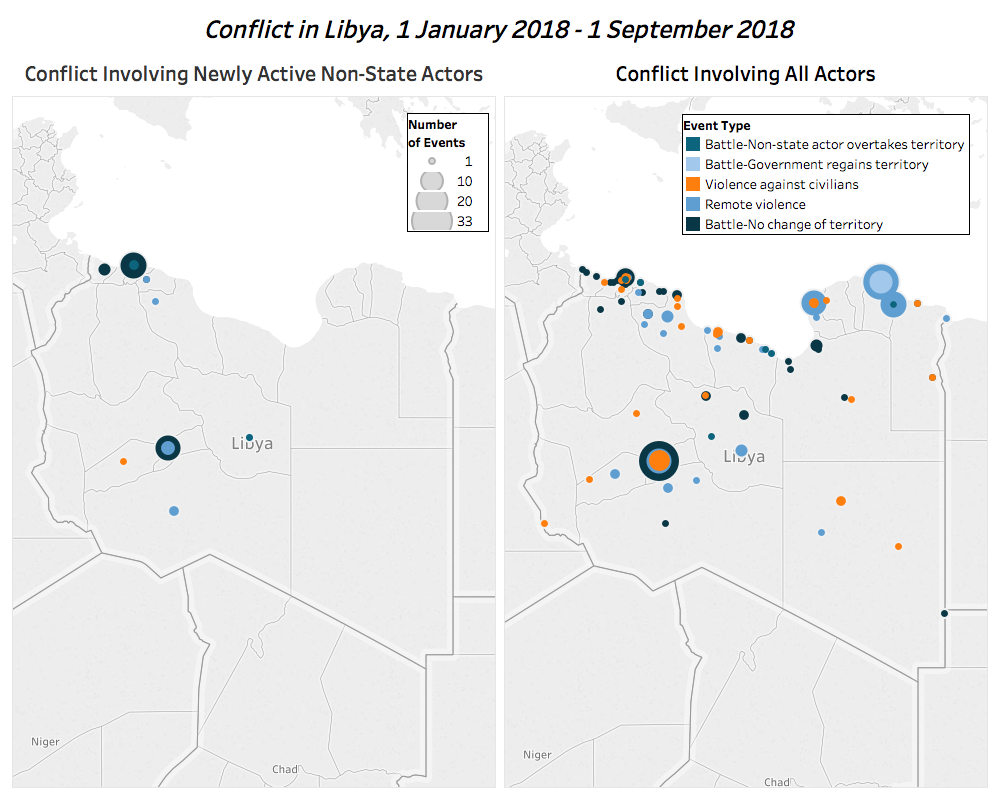

As demonstrated in the left-hand map below, these groups have made marked gains against the government in contested and target-rich environments like Tripoli. In Sabha, where the groups are also active, there have been a number of reports of inter-militia fighting; in mid-May, for instance, there were a number of reports of violent conflict between the newly active 6th Infantry Brigade and the Awlad Suleiman militias.

In at least three instances, these newly active groups have successfully won territory in conflicts against the government and have battled them without territorial exchanges in a number of other instances. Notably, some of these successes and many of the recorded events have been in Tripoli, with violence also reported in Sabha; this is in contrast to the overall pattern of violent activities in this period (demonstrated in the right-hand map below) which includes a number of events in the country’s north and west, particularly in Al Hizam Al Akhdar and Darna.

The state budget for militias is declining and increasingly precarious, prompting these groups to seek non-state revenue streams (Lacher, 2018). The newly-active militias’ activity in Tripoli reflects the institutionalization of this dynamic. As a result, “the militias are no longer merely armed groups that exert their influence primarily through coercive force. They have grown into networks spanning politics, business, and the administration” (Lacher, 2018). Others report that “letters of credit, debit cards, fuel smuggling, trafficking of subsidized products and extra-budgetary expenses have all been channels of diversion used by armed groups (and their sponsors) to finance themselves through one source: diversion of Libya state funds,” emphasizing the close relationship between these militias, corruption, and the hollowing out of the state (Libya Herald, 9 March 2018). Tripoli, as an economic and political hub, provides access to many of the alternative sources of funding that militias have turned to as their formal budgets have withered. As 2018 advances, the possibility of more militias defecting from the GNA, new militias emerging, or inactive groups re-mobilizing looms large and threatens to further complicate the security landscape and undermine stabilization efforts in Tripoli and the country more generally.

AfricaAnalysisCivilians At RiskCurrent HotspotsRemote ViolenceRioting And ProtestsViolence Against Civilians