Since February this year, a new battlefront has emerged in eastern Burkina Faso (ACLED, 2018), in the Est Region situated along the borders with Niger, Benin, and Togo is regarded as a bastion of banditry. However, militancy is a new phenomenon in this part of the country, except the reported failed attempt by Al-Mourabitoun to establish a base in the Tapoa Forest, albeit on the Nigerien side of the border (Jeune Afrique, 2016). Until recently, militancy was largely limited to the country’s northern provinces along the border with Mali, in addition to a series of high-profile attacks in the capital of Ouagadougou (ACLED, 2018).

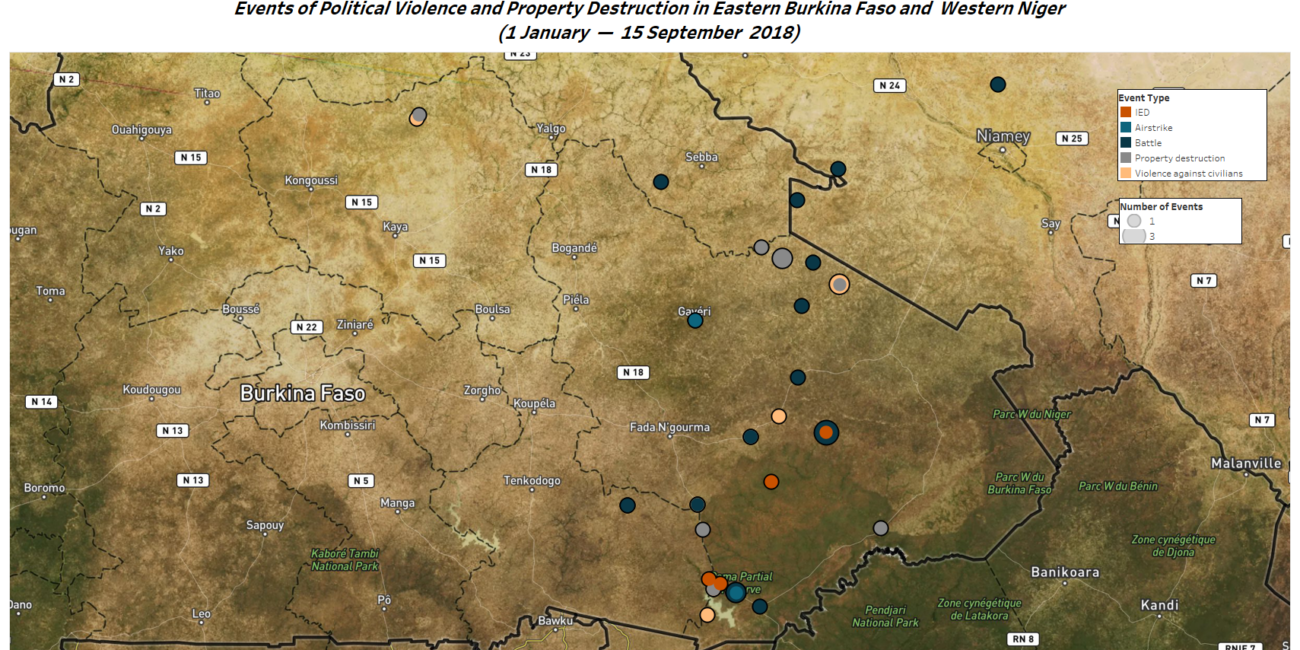

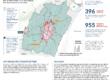

The discourse surrounding the developments in the East describes this group as a novelty or as a militancy that has moved to this part of the country. However, militants remain active in the other areas, evidently by the quasi-simultaneous attacks that have been carried out in the Est Region and Soum Province, possibly coordinated. Another important aspect is that the organization of the militants in Burkina’s East is split between the provinces of Gourma, Kompienga, and Komondjari (see map below). Additionally, the militants have proven to possess significant militant tradecraft, reflected by the manufacturing and efficient deployment of IEDs, the execution of complex ambushes, the frequency of attacks, and their multifaceted strategy. In August 2017, the first IED attack in Burkina occurred in Soum Province. Since then, there have been another twelve incidents involving IEDs in Burkina, including: six IED attacks in Soum, four in the East (including the deadliest IED attack in Burkina to date recorded in the area of Nassougou on August 11, 2018), a suicide car bomb in the capital of Ouagadougou, and a failed defusal of an IED in Soum. These are tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) that bear the hallmarks of Ansaroul Islam (CTC, 2018).

Militant presence in Burkina’s East surfaced amid pressure by French forces, aided by local militias, against the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS) in the Mali-Niger borderlands. This occurred in light of movements and attacks by ISGS militants gravitating toward the Niger-Burkina Faso border (see map below). Meanwhile, activity between Burkina’s North and East is observed, and the area of Guienbila constitutes an important transit point. On May 2, 2018, a series of attacks were carried out in Guienbila and nearby Bafina. This activity suggests that the East had become a point of convergence for elements of ISGS and Ansaroul Islam, as well as a local component reportedly composed of sons of the customary chieftaincy (Le Monde, 2018); some of these members were reported to be returnees from Mali (Sidwaya, 2018). Thus, a hybridized militant group is engendering a nascent micro-insurgency.

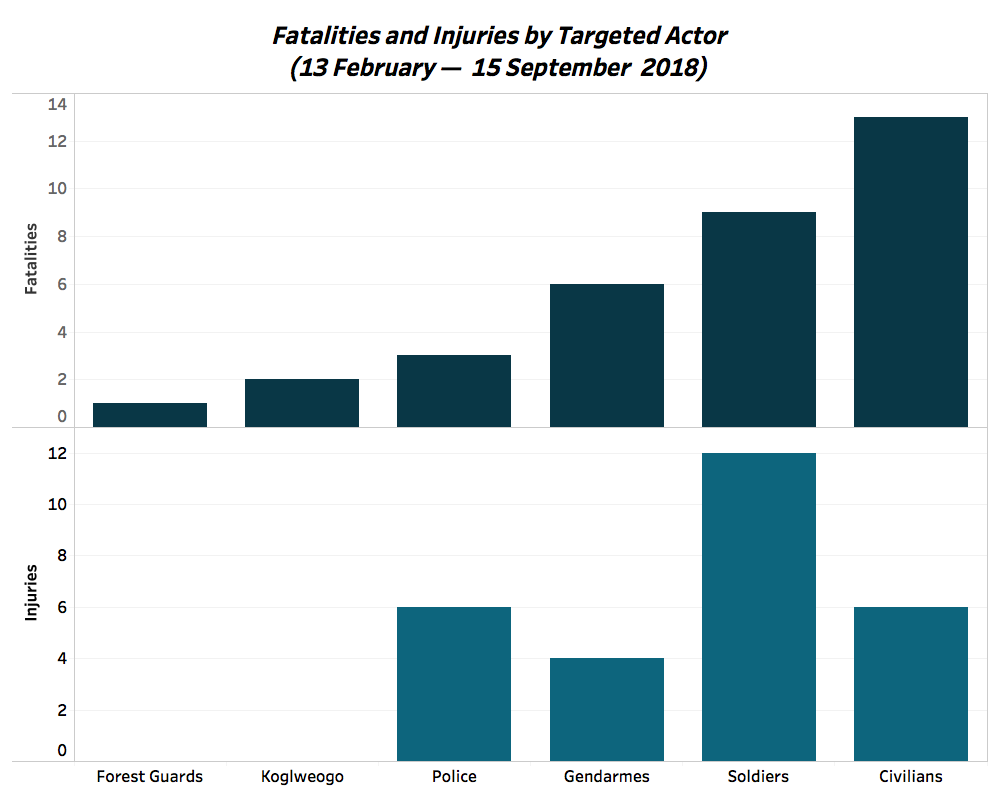

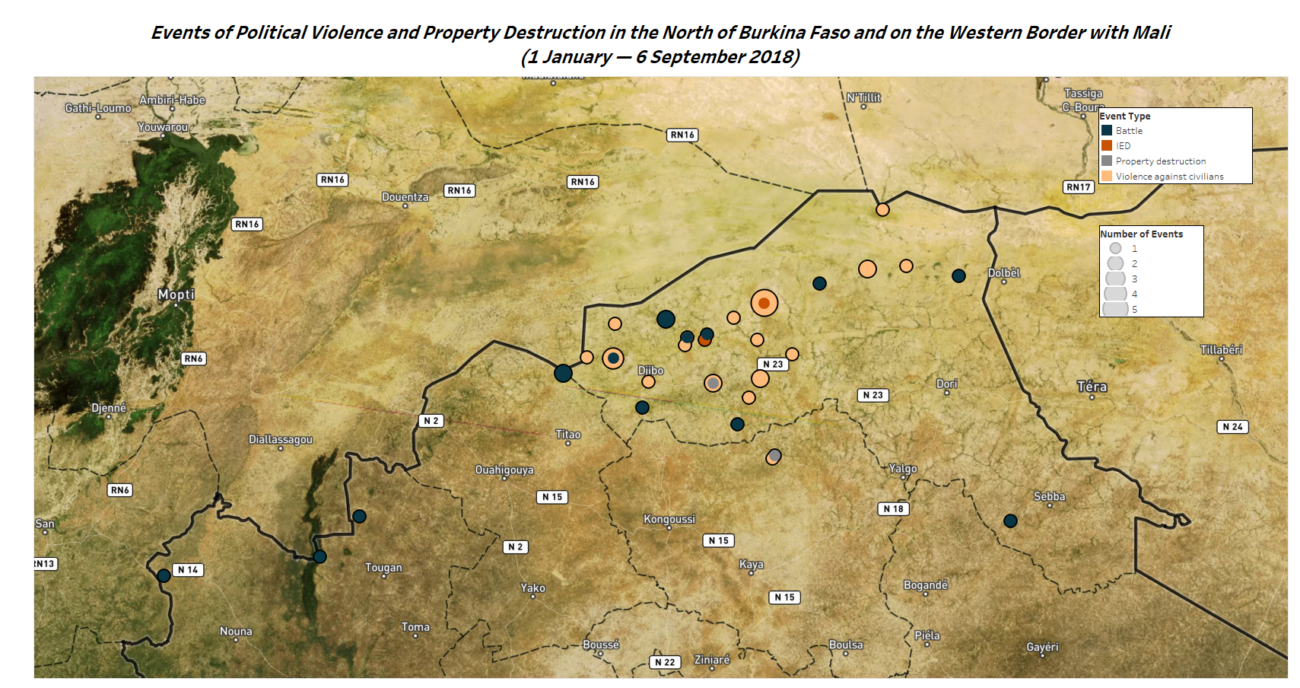

Recent activity is of great concern: 34 fatalities and 28 injuries are recorded as the result of 32 attacks in the East since February among soldiers, gendarmes, police, forest guards, Koglweogo, and civilians (see graph below), while militants have sustained 1 fatality and 2 injuries. Highlighting this, the issues which Burkina Faso has been confronting in the North since 2016 are far from solved. Hitherto this year, at least 46 attacks have taken place in the northern provinces and along the western border with Mali, with an average of 5.6 attacks per month (median value 12), according to data collected by ACLED (see map below). A string of attacks has also taken place in the southwestern part of the country. Hence, Burkina is suffering from general insecurity with multiple fronts, which it is slow and badly equipped to confront, as seen in the North where defense and security forces often have resorted to the use of scorched earth-tactics.

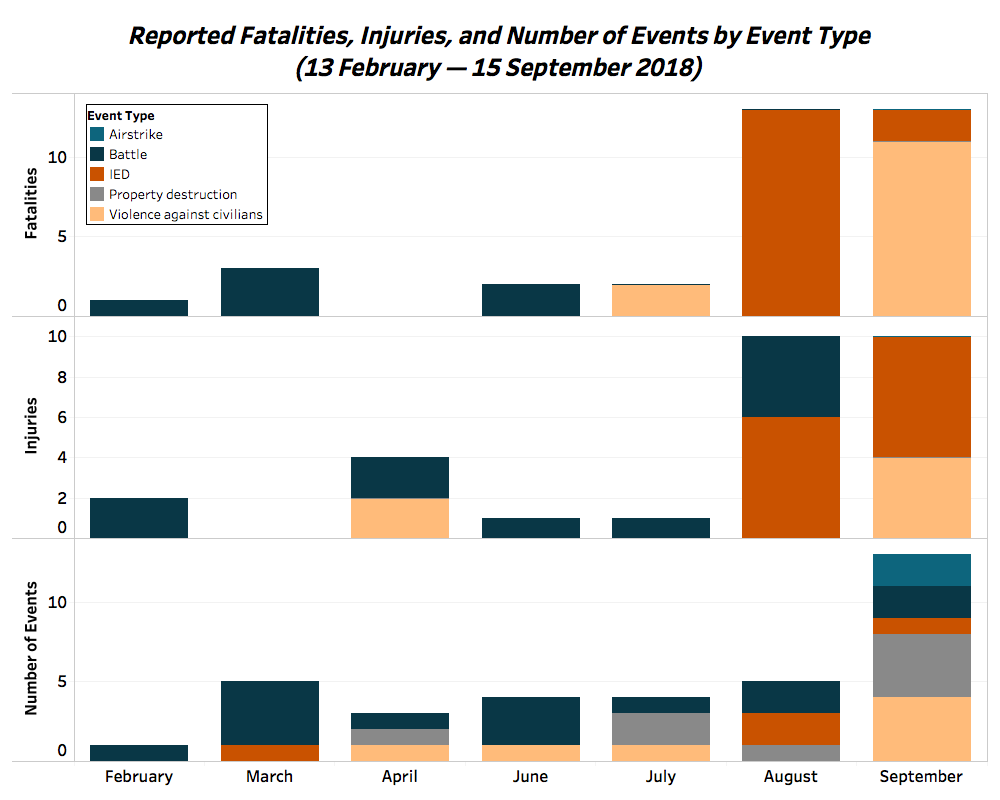

The response by Burkinabe authorities has been weak and slow (see graph below), despite attacks and casualties tripling since March 2018. A limited achievement was the dismantling of a militant camp in the village of Bakani, about 50km from Foutouri, in late March 2018 (AIB, 2018). The Koglweogo vigilante militia played a central role in the Foutouri case, losing two of their members in a battle with militants (Sidwaya, 2018). The Koglweogo itself is not a coherent structure and has intermittently complicated relations with the authorities as a community-run parallel security force. It often imposes controversial torture-like methods as punishments for crimes (La Libre, 2018), spurring outrage and conflict with locals, in addition to some members’ own involvement in criminal acts. Another question that arises is the extent of the local insurgent engagement and the alleged presence of sons of customary chiefs in militant ranks, which could complicate the local security dynamics due to Koglweogo dependency on the chieftaincy. Hence, this is a potential determinant regarding the positioning of the Koglweogo vis-à-vis defense and security forces, and other non-state actors in the changing matrix of this local space.

While militants have cemented their presence in Burkina’s East, it took months for President Roch Kabore to convene an emergency meeting with the Supreme Council of National Defense at Kosyam. No state of emergency or curfew was declared in the Est Region, notwithstanding the arguable effects such measures would have. Instead, a lot of rhetoric to the press by President Kabore—such as “[it is time to] retake the initiative in the East”, “the scourge will be eradicated” is common (Le Faso, 2018). On September 16, the general chief of staff of Burkina’s armed forces announced for the first time ever that the air force in conjunction with combing operations had conducted airstrikes against militant positions in the areas of Pama and Gayeri, resulting in the destruction of “terrorist bases”, according to the statement without providing further details regarding damages inflicted in militant ranks (Radio Omega).

In the wake of the French intervention in Mali, militant commander Adnan Abu Walid Al-Sahrawi and a group of loyal fighters established a base in the Ansongo-Menaka Partial Faunal Reserve. From there, it expanded its presence across the Mali-Niger borderlands in Mali’s Menaka Region and Niger’s Tillabery Region, fighting Malian and Nigerien forces, and local militias. The constellation implanted in Eastern Burkina Faso has established bases in the Kodjagabeli forest on the Niger-Burkina Faso border (Humanitarian Response, 2018). The localities of Bartiebougou and Tankoalou situated adjacent to the forest have come under the quasi-control of militants.

More importantly, the militants have entrenched themselves in the protected W-Arly-Pendjari (WAP) ecological complex and its surroundings: a major transboundary natural reserve connecting parks and hunting areas in Burkina Faso, Niger, and Benin (UNESCO). The natural reserve situated in the tri-state border area is of immense strategic importance and the entrenchment of the militants is of major concern. Sheltered by unpopulated, vast, dense forests, the militants have found a sanctuary with tactical benefits. This typography of inaccessible terrain for defense and security forces, in particular during the rainy season, has been further complicated by the planting of improvised explosive devices (IEDs) by militants as defensive blocks around the areas they occupy (see map above, depicting where IED attacks have occurred). The militants are conducting a process of attacking government outposts—including ranger stations, hunting camps, positions and patrols of security forces—and administrative buildings and schools (Le Monde, 2018). The militants are thus systematically emptying the natural park and hunting areas of vital infrastructure and rangers, hunters, and wildlife observers. Simultaneously, they aim at imposing their rule in the surrounding areas by eradicating public and security infrastructure. There are also emerging signs of the targeting of “communal elites”, illustrated by the killing of a former municipal councilor, a merchant, and an imam, and the abduction of a marabout.

The thick forests in the tri-state border area may provide the militants active there with substantial financial resources, should they manage to get their hands on trading routes. Consequently, they gaining revenue from the smuggling of arms, drugs, poaching, ivory, and other goods (Le Monde, 2018). A deepening symbiosis between militancy and banditry may yet occur—solidifying this nexus would further complicate the security situation in Burkina’s East and could boost the fledgling insurgency.

While militant groups have been pushed back in northern Mali and have suffered numerous tactical defeats, occupying Burkina’s East follows the pattern of militant expansion in the Sahel. Similar patterns are seen in Niger and Burkina Faso in recent years. Burkina Faso is currently the largest contributor of troops to the United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA). However, its internal security needs repeatedly question the sustainability of its troop deployment abroad. The militant threat in the East demands strengthened cross-border cooperation between Burkina and Niger, in particular along the Torodi-Foutouri axis where militants evidently move across unhindered and have established quasi-control. This area is subjected to a decades-long border dispute, which is also outside of the outlined framework of the G5Sahel Force’s area of operations, in which Burkina is one of the constituents.

AfricaAnalysisCivilians At RiskConflict MonitoringCurrent HotspotsPolitical StabilityRemote ViolenceRioting And ProtestsViolence Against Civilians