On October 7th, Cameroon held a presidential election that resulted in the re-election of President Paul Biya. Biya is now Africa’s oldest and longest-serving non-royal head of state (Washington Post, 22 November 2017). In the weeks leading up to the election, there was an uptick in violence associated with the Anglophone separatist movement in the country’s North-West and South-West regions. This violence has continued into the post-election environment. 29 of the 43 violent interactions between the Ambazonian separatists and the Cameroonian government have been in the weeks after the week of the election. The Cameroonian security sector has been particularly reliant on violence against civilians in recent months. Violence against civilians by the armed separatists has not changed dramatically in recent months, but has been a consistently deployed tactic. Both the Cameroonian government and the armed separatists are using violence to screen civilian populations and punish them for perceived support of their opponents.

Increase in Violence, the Regional Division

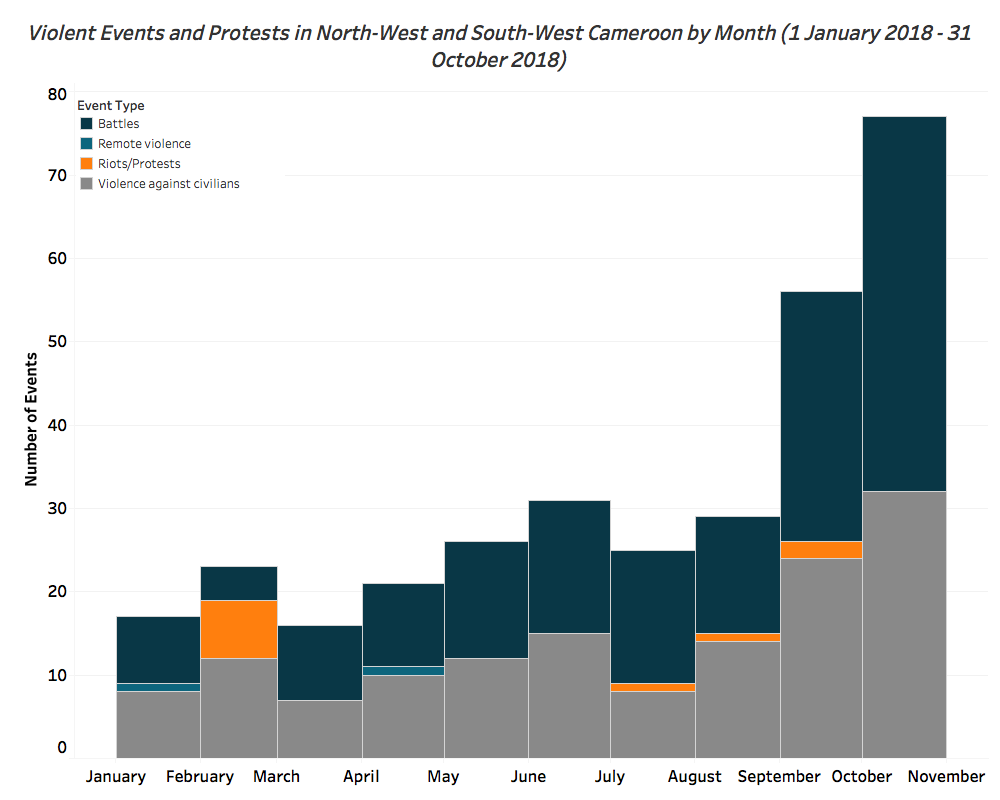

As illustrated by the graph below, in the weeks before the elections, there was a significant increase in the number of battles between armed groups and the Cameroonian government in the North-West and South-West regions. The number of battles in these provinces increased by more than 300% from August 2018 to 45 events in October 2018. Much of this was driven by an increase in the number of violent conflicts between the anglophone separatists and the government’s forces.

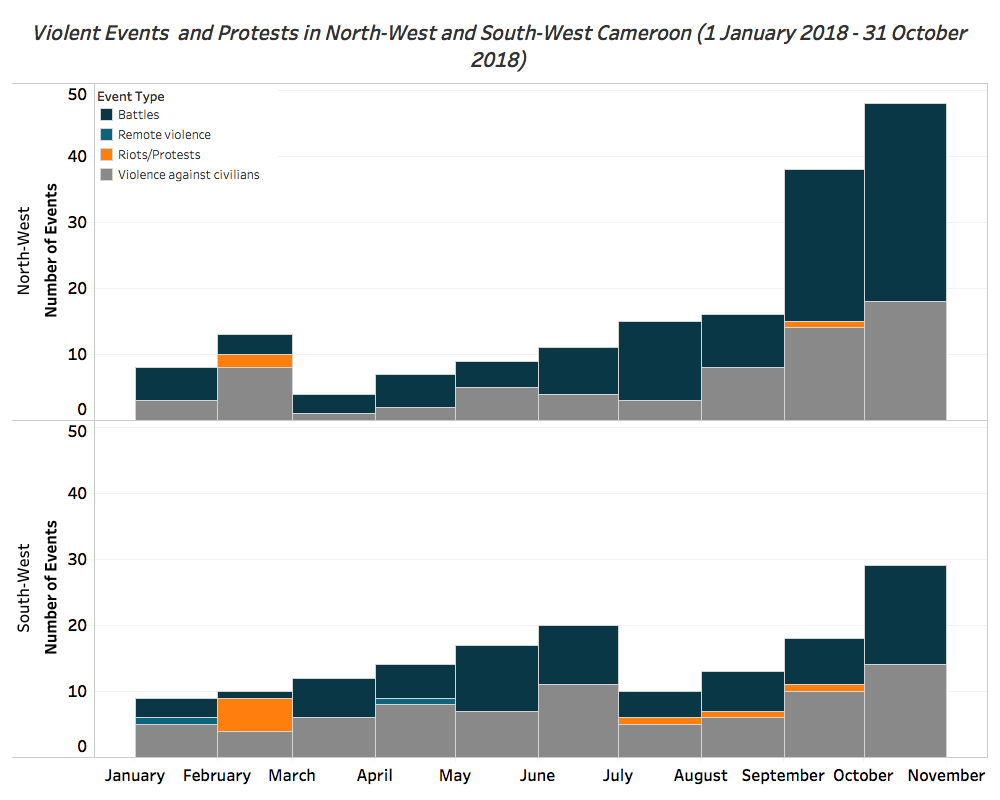

Though there was an increase in the number of violent activities in both the North-West and South-West regions in the run up to the October elections, two-thirds of the battles in October 2018 were in the North-West region. As the graph below illustrates, the divergence in the proportion of violence in each region became pronounced in September 2018. This timing suggests that the relative concentration of violence in the North-West may be a result of pre-election strategies and incentives. The different patterns of violence between the two regions speaks to the fragmented nature of the conflict. The armed separatist movement in Cameroon is comprised of a variety of armed groups – and these groups may have different tactical capabilities and relationships with their communities.

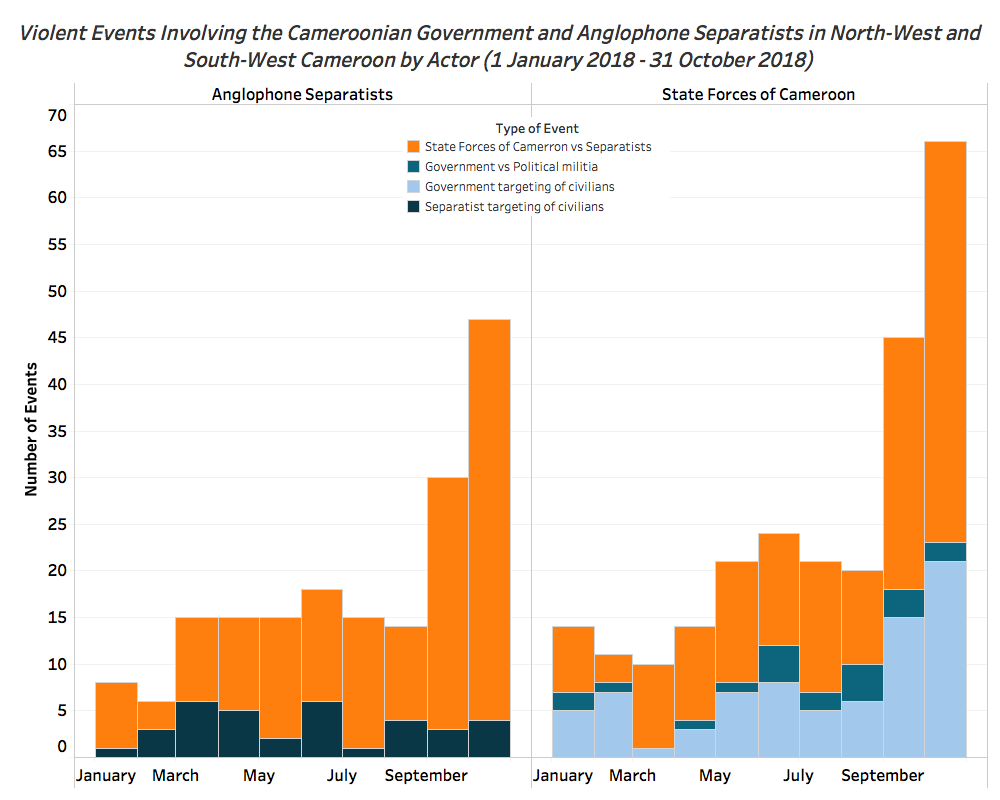

As the number of battles between armed anglophone separatists and the Cameroonian government increased, so did the number of instances in which civilians were targeted. The graph below demonstrates that much of this increase in civilian targeting was at the hands of the Cameroonian government. In October 2018, nearly 32% of the Cameroonian government’s activities in the North-West and South-West regions involved targeting of civilians, as compared to nearly 9% of anglophone separatist activity over the same time period.

The graph above illustrates that, while anglophone separatist violence against civilians has remained relatively constant in recent months, the government ramped up its targeting of civilians in the months leading up to the elections. In October 2018, there were 21 instances of civilian targeting, as compared to 6 in August and 15 in September.

Why Both Sides Might be Targeting Civilians

Research has suggested that secessionist movements will typically avoid targeting civilians; some work suggests that this is because these armed groups care about their reputation within the international community and because of a lack of incentive to inflict harm on ‘their’ population, particularly in situations in which their military strength cannot extend past ‘their’ territory (Fazal, 2018). Within the context of the anglophone separatist movement, much of the violence directed towards civilians seems to be a way of screening who supports the separatist movement and who does not — and punishing those that they see as defying their directives. In the South-West, for example, Anglophone separatists used machetes to chop off the fingers of workers on a state rubber farm, who the rebels had previously warned not to go to work (Washington Post, 2 November 2018). Similarly, the separatists kidnapped dozens of young men from their school, seemingly as a punishment for defying the group’s calls for a boycott of schools (The Guardian, 5 November 2018).

The surge in government targeting of civilians in North-West and South-West provinces may have been a way of trying to suppress opposition in the run-up to the elections. It may also be a function of the security sector’s lack of integration into the local population. The diffuse and fragmented nature of the anglophone separatist movement may make it more difficult for the Cameroonian security sector to differentiate between militants and civilians.

Moving forward

The continued violence in North-West and South-West regions, even after the elections, suggests that the conflict is unlikely to draw to a close in the near future. Civilians in both North-West and South-West Cameroon face threats from separatists for defying their anti-state dictates, as well as from the state security forces. This insecurity has prompted many to flee. As of August 2018, an estimated 246,000 people were internally displaced; election-related violence has likely increased that number (ACAPS, 17 October 2018). The competition between separatists and the Cameroonian government has left civilians in the crosshairs.