To access a PDF of this report, please click here.

According to recent World Bank estimates, rural areas account for two thirds of the Yemeni population, while only one third of Yemenis are estimated to live in urban centres (World Bank, 2018). As a result of this disproportion, the consequences of both the conflict and the humanitarian crisis have become even more catastrophic for Yemen’s most fragile and remote communities. However, although much of the conflict continues to be fought outside urban areas, Yemen’s cities constitute the main political battleground for all of the factions involved in the conflict.

Sana’a is the capital of the Houthi-backed Supreme Political Council while the internationally-recognised government, led by President Abdrabbuh Mansour Hadi, operates temporarily from Aden. Ta’izz and Hodeidah are, respectively, the longest and the most recent urban fronts of the four-year-long conflict. Independent provincial governors in Marib and Mukalla largely operate as autonomous actors, providing an alternative model to a central government widely perceived as inefficient and corrupt. In each of these cities, however, a variety of state-backed forces, rebel groups, and militias have emerged, resorting to different forms of violence and producing distinct wartime political orders.

This report explores the nature of the conflict in Yemen’s four main cities, providing a disaggregated analysis of urban violence in Sana’a, Aden, Ta’izz, and Hodeidah[1]. Accounting for approximately half of Yemen’s total urban population, these environments continue to be an arena of intense political struggles, where an array of armed groups and elites compete for power shaping the country’s political trajectory. As such, they constitute the intersection of the local, national, and regional dimensions of this conflict.

The report highlights three main points. First, armed violence is a reflection of the political nature of the conflict. Variations in the geography and intensity of the conflict countrywide typically follow changes occurring at the political level, such as fragmenting local alliances or consolidating international alignments. This shows that a military solution to the conflict – which several actors are seeking – is unlikely to bring violence to an end without a comprehensive political settlement.

Second, the non-unified character of the Yemen conflict is a major obstacle for its resolution, hindering the composition of the several overlapping fault lines and the coordination among a composite group of political actors. The fragmentation of Yemen’s conflict landscape contributed to the proliferation of several armed groups, which led to increased infighting within the warring camps. In addition to agreeing on a new political framework at the national level, the emergence of a peaceful political settlement therefore requires addressing the local drivers of armed violence in each of Yemen’s urban environments.

Finally, the international dimension has contributed to further complicating the resolution of the war by inciting rent-seeking and spoiler behaviour. There is large evidence that international actors involved in Yemen have provided political and material support to local agents who agree to promote their patrons’ agendas, often entering into competition between one another. Far from containing centrifugal forces, this has resulted in short-term alliances and shifting loyalties in each of the cities analysed in this report.

Sana’a: The besieged Yemeni capital between coalition air strikes and Houthi repression

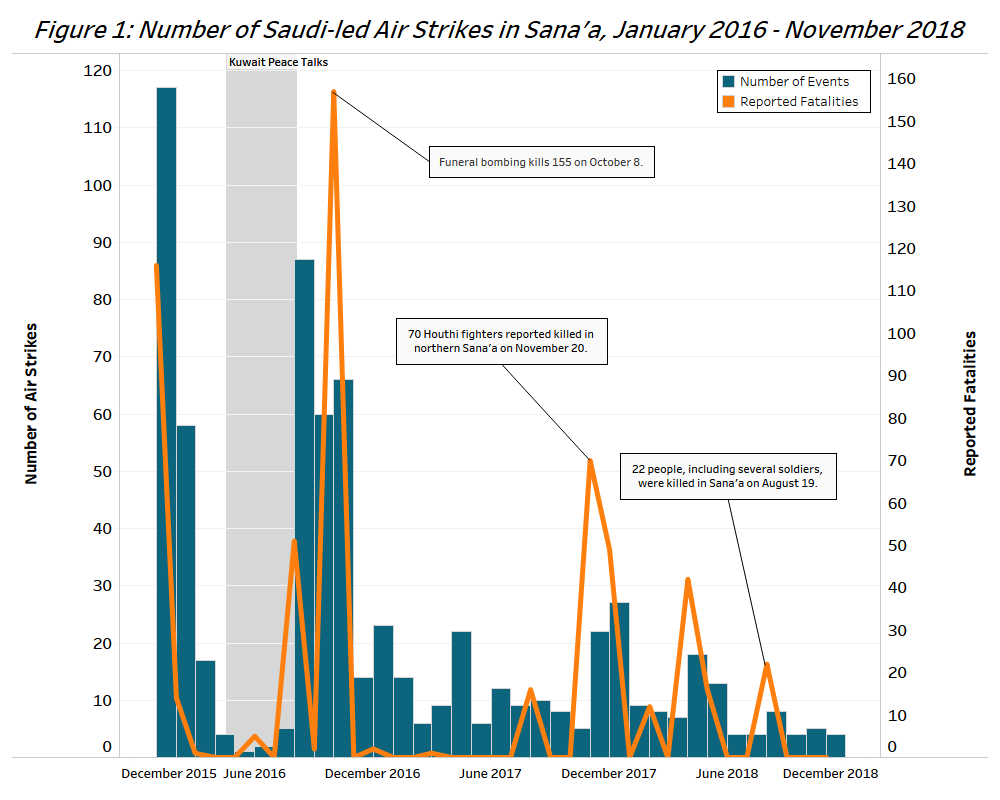

Since the beginning of the Saudi-led Operation Decisive Storm in March 2015, the Yemeni capital Sana’a has been targeted by an intense air campaign that has killed an estimated 576 people between January 2016 and October 2018, including at least 281 civilians (see Figure 1). In October 2016, Saudi war jets launched a double-tap strike on a communal hall south of the capital, where senior government and military figures had gathered for the funeral of the late father of Jalal Al-Rowaishan, a close ally of former president Ali Abdullah Saleh and Minister of Interior of the Houthi-led Supreme Political Council. The bombing, which amounted to an “apparent war crime” (Human Rights Watch, 13 October 2016), constitutes one of the deadliest events in the conflict. Data collated by ACLED in cooperation with the Yemen Data Project show that the number of air strikes hitting the capital has largely declined since the beginning of the Saudi-backed intervention. In 2017, ACLED recorded 150 air strikes, down from the 454 bombings recorded in 2016 despite the nearly complete stop to the operations during the Kuwait peace talks in the summer of 2016. Should current trends for 2018 continue until the end of the year, the number of air strikes in Sana’a is set to decline further and not expected to exceed 100 – a remarkable difference compared to 2016, when 117 air strikes were recorded in the month of January only.

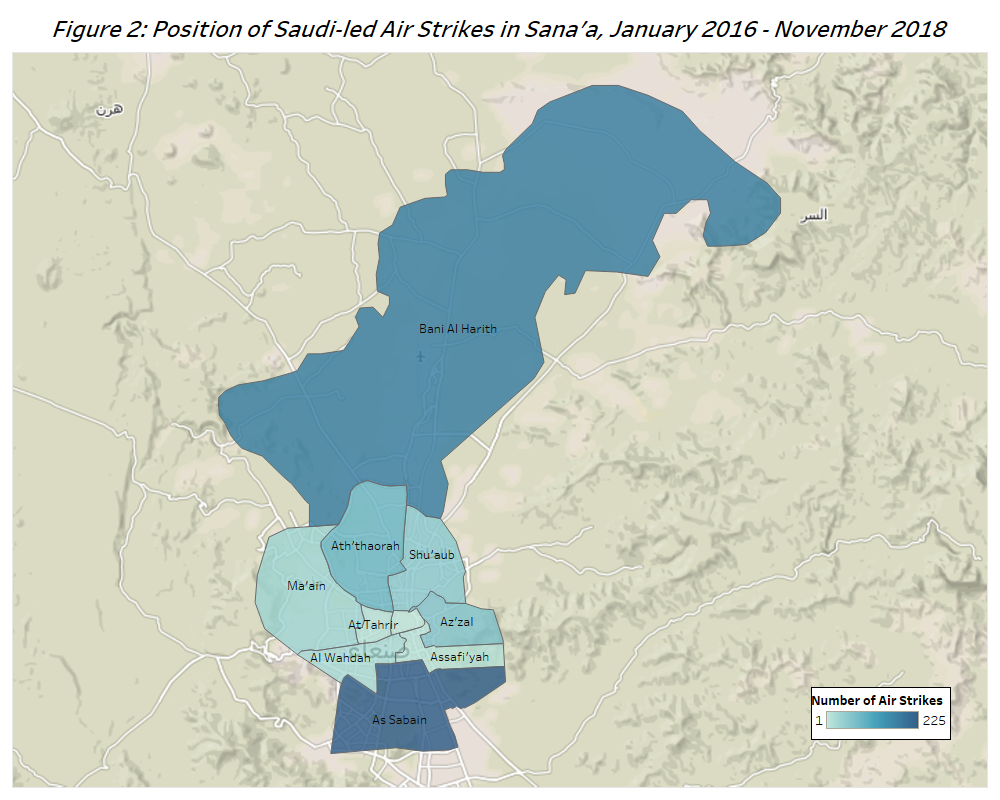

More than 50% of all air strikes reported in the capital area since 2016 hit As-Sabain and Bani Al-Harith districts, which house strategic military sites and government buildings (see Figure 2). Among the locations more frequently hit are the military bases Jabal An-Nahdayn (at least 102 strikes), Faj Attan (74 strikes) and the Al-Dailami air base, located next to Sana’a international airport (84 strikes). The Saudi-backed air campaign, however, has not spared civilian targets, such as food factories (The Guardian, 9 August 2016); medical facilities (Yemen News Agency, 5 April 2017); schools (Yemen News Agency, 7 November 2017); and the capital’s Old City, a UNESCO World Heritage site that has suffered heavy damage since 2015 (Mwatana, 15 November 2018). These incidents, together with several other episodes reported across Yemen, call once again into question the Saudi-led coalition’s ability to contain the damage produced by air strikes, pointing instead to a deliberate attempt at destroying civilian infrastructure in Houthi-controlled territories (Mundy, 9 October 2018).

After Saleh’s attempt to switch sides in December 2017, Sana’a was the theatre of major clashes between Houthi forces and Saleh loyalists, which resulted in 234 people killed, and culminated with the assassination of the former president (ACLED, 16 February 2018). These events constituted a major turning point in the conflict, as the weakened Houthi forces began to suffer serious setbacks in Shabwah and on the western front, where coalition-backed forces made important territorial advances. They also set in motion new political dynamics in the capital, where the Houthis have ruled since 2015 in an uneasy coalition with the General People’s Congress (GPC), the party of the late president Saleh.

Left without its founder and leader, the Sana’a faction of the GPC is considered to have lost much of its agency. Leading party members were reportedly arrested in Sana’a (Sahafah, 12 December 2017; Barq Press, 14 January 2018); others, fearing for their lives, were forced to leave the capital (Barakish, 10 January 2018). In January, the party elected long-time Saleh ally and former minister Sadiq Amin Abu Ras as its new leader, although the Houthis are said to supervise his work and to have conspired to replace him with a Houthi loyalist (Middle East Eye, 23 January 2018; Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, July 2018).

These events, along with an increasing number of cabinet reshuffles enacted in the past few months (26 September Net, 12 May 2018; Khabar Agency, 29 July 2018), reflect the Houthis’ concerns about internal stability. While the coalition’s air campaign and the Saudi-enforced blockade have not resulted in provoking an anti-Houthi uprising, the Houthis fear that local actors, including some of their current allies, may seize any opportunity to openly challenge their rule. Between October and November, at least three ministers of the self-styled Houthi-backed National Salvation Government fled Sana’a, defecting to the coalition, while others are suspected of planning to imitate their former colleagues[2].

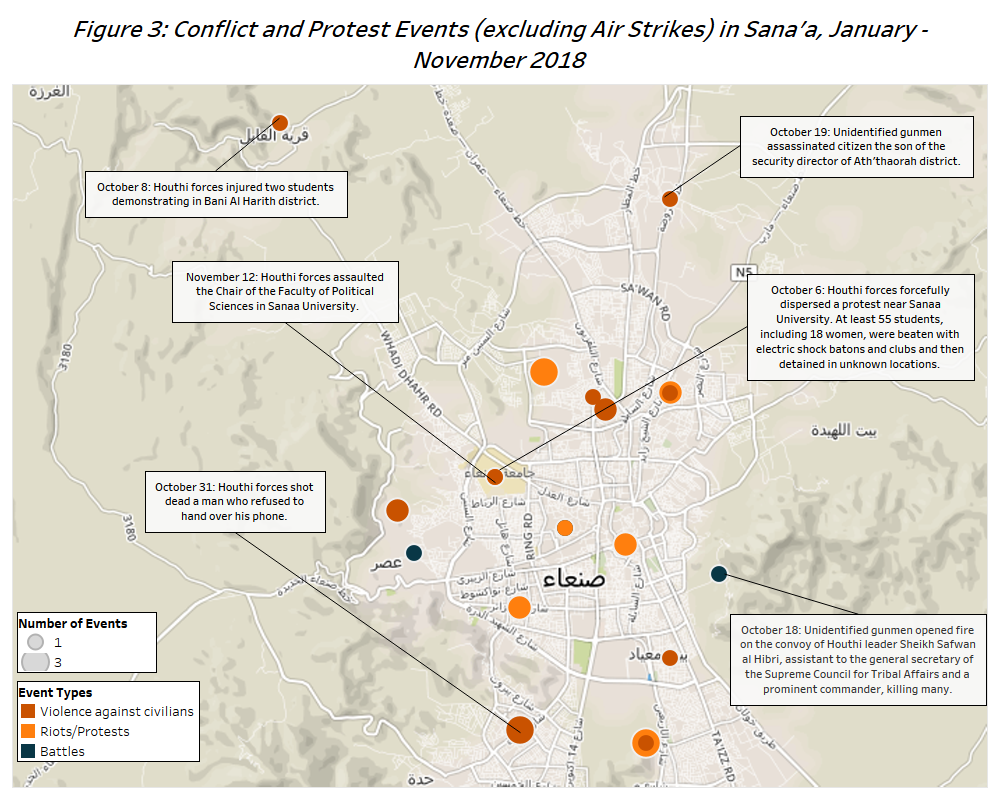

Sporadic assassinations (Al-Arabiya, 27 January 2018) and recent demonstrations against the deteriorating state of the economy are additional factors of insecurity for the Houthis in Sana’a (see Figure 3), pointing to why the movement is increasingly intolerant towards dissent. In early October, police forces aided by Houthi militias reportedly assaulted and detained young students demonstrating against economic mismanagement in at least two separate protest events in the capital (Gulf News, 6 October 2018; Bawabitii, 8 October 2018). Following these events, Houthi authorities introduced a new regulation ordering demonstrators to request permission to hold a public gathering. At the same time, journalists continue to face arbitrary arrests, detention, and intimidation: according to the Yemeni Journalists’ Syndicate, more than ten reporters remain detained in Houthi-run prisons, while twenty more were temporarily arrested following a raid on a civil society event in late October (Committee to Protect Journalists, 10 July 2018; Al-Masdar, 25 October 2018).

As of early December 2018, coalition-backed government forces are not set to retake Sana’a soon. Despite intense ongoing fighting 50 km northeast of the capital, at the border between Ma’rib and Sana’a governorates, Houthi forces have managed to hold territory and secure support from local tribes. Sporadic violent clashes between the Houthis and the tribesmen reported in the past few months are unlikely to escalate into an all-out uprising, as the late president Saleh seemed to hope in calling for the coalition’s support in December 2017[3]. However, their support rests ultimately on the Houthis’ ability to sustain the patronage-based system in the territories they control; should they lose Hodeidah and suffer setbacks in other key regions across Yemen, the Houthis may find it increasingly difficult to rein in their pragmatic allies.

Aden: Enduring insecurity in Yemen’s temporary capital

As Sana’a continues to remain under Houthi occupation, Aden has become the de facto seat of the internationally-recognised government of Yemen. Despite its temporary status as Yemen’s capital, Hadi and his ministers largely operate from Riyadh, facing criticism for their sporadic presence while the southern port city continue to face a variety of challenges, including a fragmenting political landscape, chronic insecurity, and a collapsing economy. At the same time, Aden is the intersection of internecine struggles involving local, national, and regional actors seeking to control the city and extract profitable rents.

In March 2015, shortly after Hadi fled from his house arrest in Sana’a to Aden, Houthi-Saleh forces attempted to seize the city — sparking one of the deadliest battles of the Yemen war. According to official UN estimates, thousands of people, including hundreds of civilians, were killed in Aden as a consequence of intense ground fighting, artillery shelling, and air strikes, although there are no consolidated figures confirming the overall fatality toll (UNOCHA, 20 July 2015)[4]. The Houthi-Saleh coalition retreated from the city in late July after a 100-day battle, leaving behind thousands of landmines, a deteriorated humanitarian situation, and a security vacuum that several militias and Islamist groups were quick to fill (Human Rights Watch, 5 September 2015). The Yemeni government’s inability to re-establish its authority in Aden after the defeat of the Houthi-Saleh forces partially explains the challenges the city is currently facing, and illustrates the limited legitimacy Hadi and his government enjoy in Yemen’s temporary capital.

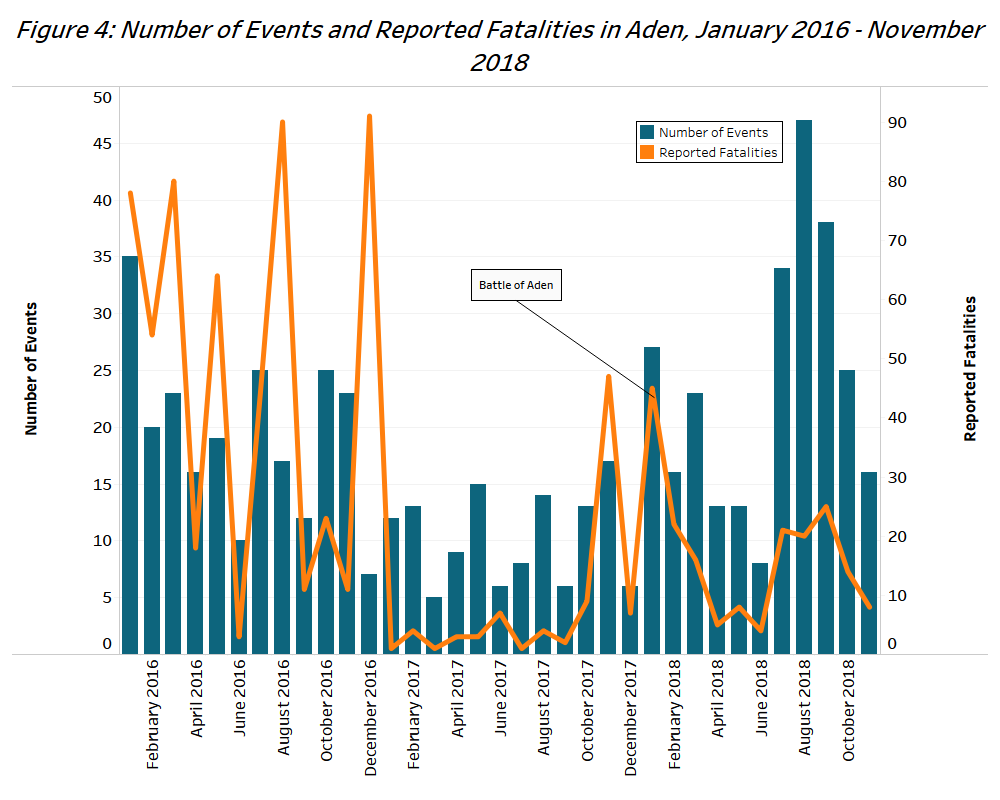

Discontent with the Hadi government escalated in March 2017, after the President dismissed Aden governor Aidarus Al-Zubaidi, a fifty-year-old army general from Ad-Dali, and Minister of state Hani bin Braik, founder of the paramilitary Security Belt forces. After a series of protest rallies held in Aden and across southern Yemen, on 11 May Al-Zubaidi established the Southern Transitional Council (STC), a political organisation that includes several ministers, governors, and other political and civil society figures demanding independence for southern Yemen (Reuters, 11 May 2018). In Aden, events took a violent turn in late January, when pro-Hadi security forces prevented STC supporters from holding a demonstration in Khormaksar, sparking a three-day-long battle that claimed the life of at least 40 people (ACLED, 16 February 2018). Overall trends in political violence and protest are visualised in Figure 4.

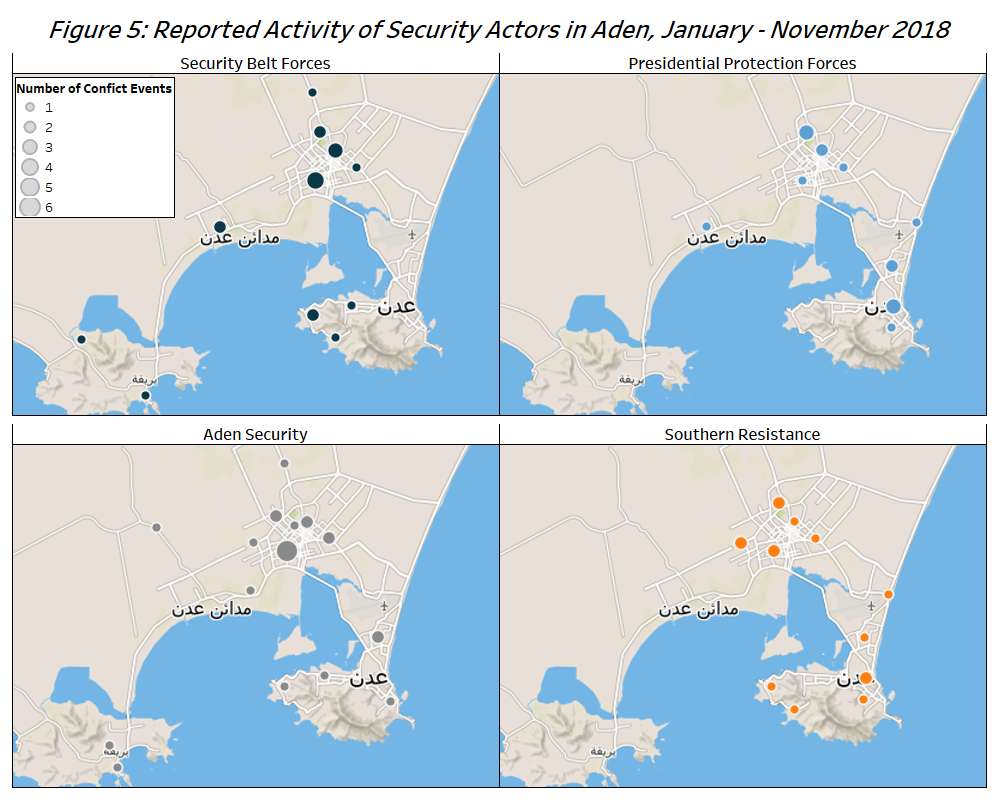

As a consequence of the battle, STC-affiliated armed groups consolidated their control in several districts of Aden[5]. The Security Belt forces — an Emirati-backed counter-terrorism group present in Abyan, Ad-Dali, and Lahij governorates and comprised of secessionist and Salafist fighters — have reportedly taken over the districts of Burayqah and Ash Shaykh Othman while also setting up checkpoints and extending their activity into Mansura, Craiter, and Dar Sad areas (Chatham House, 27 March 2018). The group is accused of forcibly disappearing dozens of people and using torture in the Bir Ahmed detention facility in Burayqah, which they run in cooperation with the United Arab Emirates (UAE) (Human Rights Watch, 22 June 2017; Associated Press, 9 July 2018; Amnesty International, 12 July 2018). Up to 15,000 fighters are reportedly fighting in the Security Belt forces, which virtually remain under the formal command structure of Yemen’s Interior Ministry despite reporting to the UAE and operating largely as an independent militia. In Aden, they are led by Munir Mahmoud Ahmed Al-Mashali, aka Abu Yamamah Al-Yafei, although many Security Belt commanders hail from the Yafi’i region in Lahij, leading to speculations about the under-representation of Aden in the security architecture of the STC (International Crisis Group, 23 May 2018; Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, 5 August 2018)[6].

Following clashes at Aden airport in January 2017 and across the city the following year, Hadi-backed forces were instead forced to hand key sites over to the STC (Chatham House, 27 March 2018). The Presidential Protection forces, hailing predominantly from Hadi’s home region of Abyan, guard the Presidential Palace in Craiter, though are also present in Khormaksar, Dar Sad, Ash Shaykh Othman, and Burayqah, where their troops were attacked on multiple occasions in 2018.[7] In August, Hadi accused the 1st Brigade of the Security Belt forces of having conducted an attack against the Salah Al-Din military college in western Aden, causing the death of one soldier (Middle East Monitor, 20 August 2018).

The districts of Ma’alla and Tawahi house the headquarters of the Aden Security, led by separatist leader Shalal Shaye’a, while another UAE-backed militia commanded by Muhammad Al-Khalili controls Aden’s international airport. Other UAE-, Hadi- and non-affiliated militias, collectively known under the umbrella name of ‘Southern Resistance’ despite representing a variety of political orientations, are reportedly active across the city, sporadically clashing with other armed groups over the control of checkpoints (Chatham House, 27 March 2018). The map below shows the reported areas of activity of paramilitary and militia groups in Aden throughout 2018.

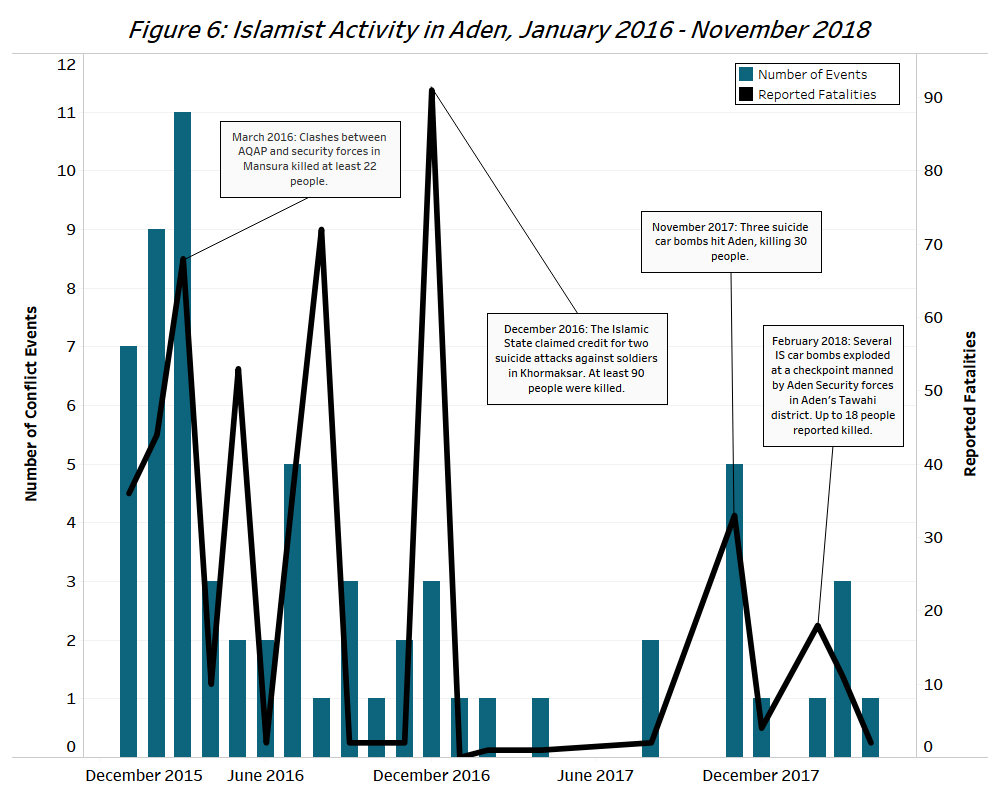

Aden’s intricate security architecture has produced mixed results. On the one hand, several counter-terrorism operations have succeeded in decimating militant cells linked to Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) and the Islamic State, which were particularly active in the northern districts of Dar Sad, Ash Shaykh Othman, and Mansura. These groups are responsible for several attacks targeting military forces and civilians in Aden, which reportedly killed hundreds of people. In the past two years, their activity has significantly subsided, with only 14 events involving AQAP and Islamic State militants reported in 2017 and 2018, compared to 52 in the previous year (see Figure 6). Despite these declining trends, AQAP cells continue to sporadically operate in Aden, claiming responsibility for the assassination of the deputy commander of Abyan Security Belt forces in mid-November (Twitter, 26 November 2018).

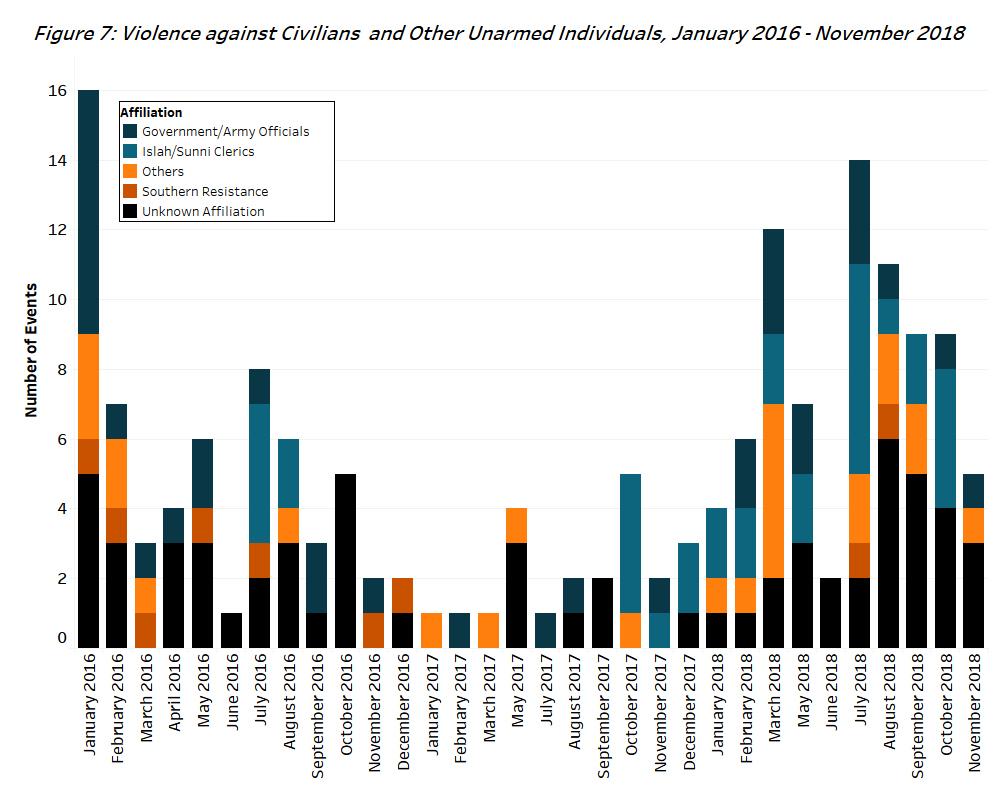

On the other hand, a string of assassinations has targeted prominent military, political, religious, and civil society figures since 2016 (see Figure 7). According to ACLED data, there were at least 53 assassination attempts against moderate Sunni clerics and Islahis between 2016 and 2018, resulting in 32 people reportedly killed, 26 of which in Aden specifically (ACLED, 8 November 2018). The UAE is suspected to have orchestrated the killings to eradicate Al-Islah from Yemen’s south, in an attempt to weaken a movement they consider to be the Muslim Brotherhood’s local wing. Although they are typically executed by unknown gunmen, in at least one case – the assassination attempt against the leader of Al-Islah in Aden Anssaf Ali Mayo in December 2015 – the UAE turned out to have provided assistance to a commando of US mercenaries (Buzzfeed, 16 October 2018). Since 1 November, no assassination attempts targeting religious or civic leaders have been recorded. This lull coincided with a meeting between the Al-Islah leadership and the UAE’s influential crown prince Mohammed bin Zayed in Abu Dhabi, which may reflect a possible rapprochement between the two parties (Middle East Eye, 14 November 2018). These developments, however, do not reflect an improved security situation: in the same month, senior tribal and military figures affiliated with both the Hadi and the STC camps were targeted in at least six distinct assassination attempts, revealing growing hostilities between the opposing factions present in the city[8].

Since Houthi-Saleh forces were driven out of Aden, the Hadi government has struggled to reassert its authority in Aden. The former capital of southern Yemen today resembles a “theatre of militias” (NTH News, 17 October 2017), where local and regional actors take advantage of a fragmented security situation to extend their influence across the city. However, rather than a cause of the current predicament, the emergence of separatist sentiments and of the STC reflect existing popular discontent with chronic insecurity, lack of basic services, economic mismanagement, and rampant corruption, for which the Yemeni government and its local allies are held responsible (The New Arab, 8 May 2018; International Crisis Group, 23 May 2018; Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, 5 November 2018). In this context, failing to provide tangible improvements to living conditions in Aden is likely to make the recent cabinet shake-up[9], and the appointment of a new governor of Aden[10], appear more as cosmetic elite reshuffles rather than substantial changes.

Ta’izz: The longest-running front-line of the Yemeni civil war

Amid their rapid land grab southward, launched from their northwestern stronghold of Sadah in late 2014, Houthi and affiliated forces started entering the city of Ta’izz, the third largest-city in Yemen, on 22 March 2015 (Reuters, 22 March 2015). Local forces, backed by Saudi-led coalition air strikes, quickly mobilised to fight the Houthis and their allies, eventually recapturing the city. The subsequent siege, however, compounded by both internal rivalries within the anti-Houthi front and an apparent decreasing interest of the Saudi-led coalition in restoring stability to the city, have made Ta’izz the longest-running battlefront of the civil war. According to data collated by ACLED, intense street fighting and indiscriminate shelling on residential areas have made Ta’izz the urban setting which has suffered the highest civilian death toll[11]; all the warring parties in the city have been accused of committing grave human rights violations that “may amount to war crimes” (Mwatana, 6 November 2016).

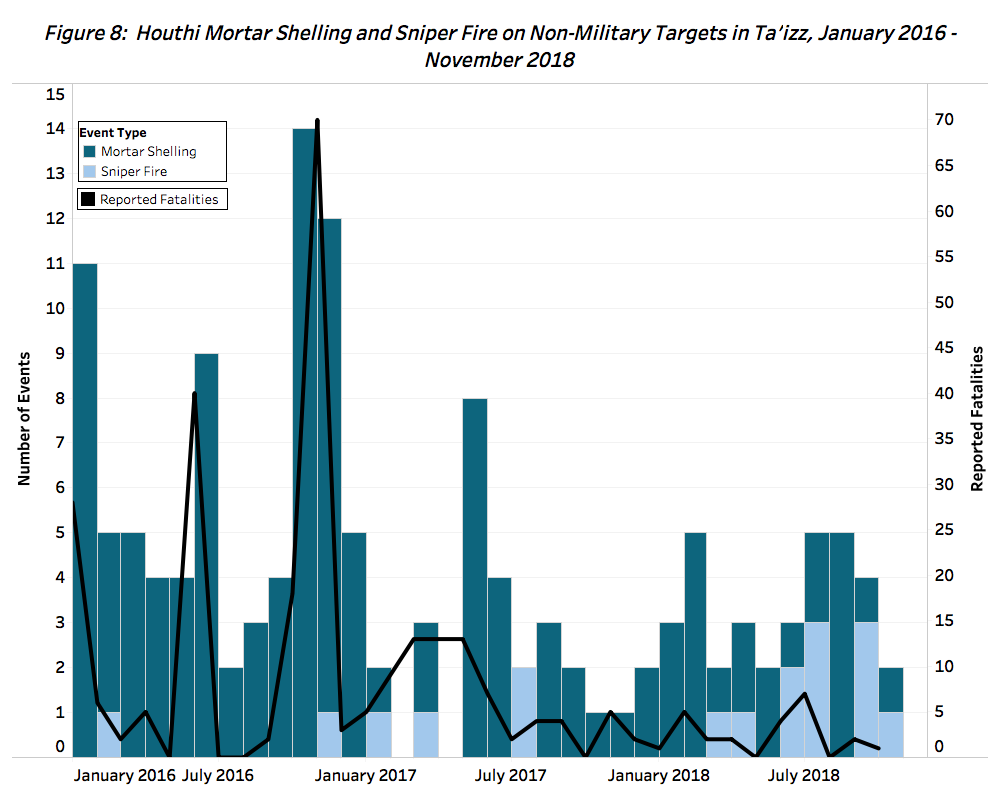

Local mobilisation, widely referred to as the “Popular Resistance” and initially led by Hamoud Said Al-Mikhlafi, managed to oust Houthi forces and affiliates out of Ta’izz. On 4 August 2015, the Yemeni Interior Ministry announced the control of 75% of the city (Al-Arabiya, 5 August 2015). These early successes, however, failed to develop into an all-out victory. As they retreated to the mountainous areas surrounding Ta’izz after the counter-offensive of anti-Houthi forces, Houthi and affiliated fighters imposed a siege on the city. Although anti-Houthi forces managed to partially break the blockade by opening a small mountain road south of Ta’izz in March 2016 (Chatham House, 20 December 2017), residents continued to be subjected to “unrelenting” mortar shelling and sniper fire from Houthi-held positions (Human Rights Watch, 18 September 2017).

While Figure 8 below shows that pro-Houthi forces have considerably decreased their shelling of non-military targets in the city of Ta’izz since the second half of 2017, sniper operations targeting civilians seem to be increasing. The fatalities associated to both mortar shelling and sniper fire, however, have steadily declined.

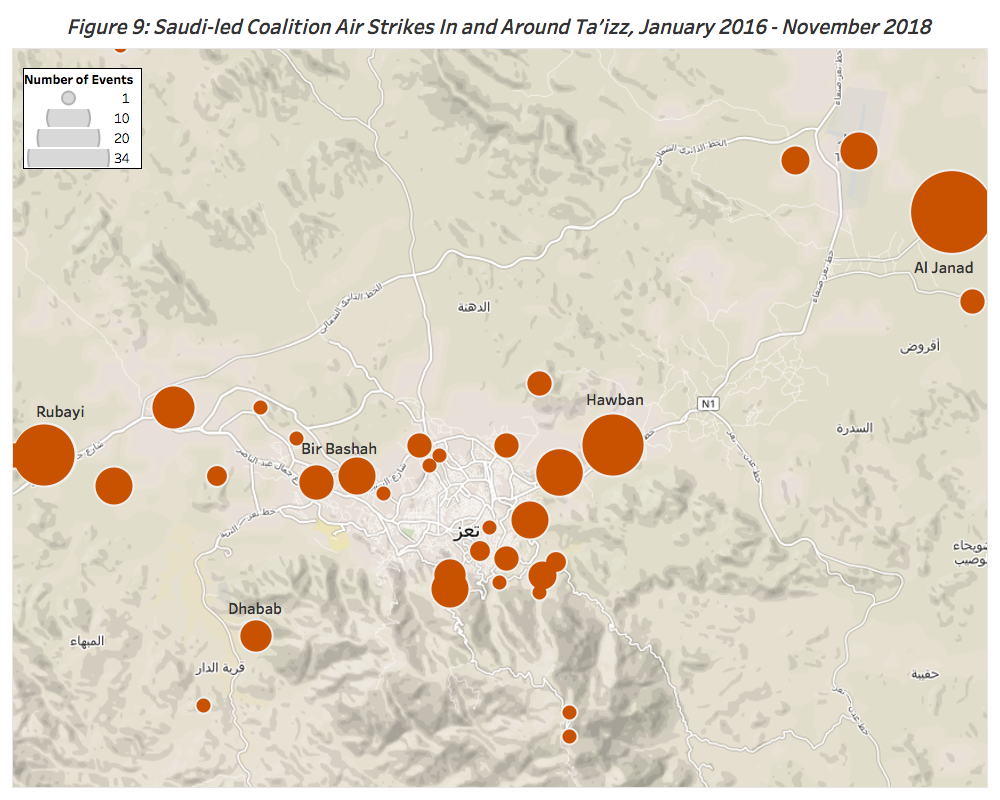

As Houthi and allied forces were driven out of the central areas of the city in late 2015, Saudi-led coalition air raids appear to have largely avoided striking downtown Ta’izz from January 2016 onward. According to Figure 9 below, they have instead focused on areas of military presence around the city[12].

Houthi and affiliated forces are principally based to the northeast of the city, in the Hawban and Janad areas, where ACLED has reported the highest number of raids. The Hawban industrial area hosts a number of factories that bring the Houthis a total annual revenue of around 50-60 million USD in tax collection – an important lifeline for the movement (Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, 4 November 2017). West of the city, pro-Houthi forces are based in the Rubayi area. In between, Saudi-led coalition warplanes have targeted the active fronts of Bir Bashah and Dhabab, and that of the eastern outskirts of Ta’izz.

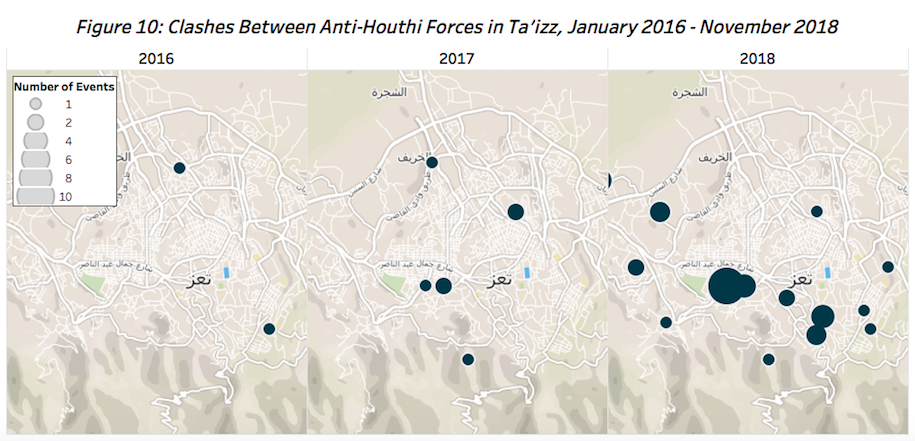

Within the city, military forces theoretically fall under the authority of the internationally-recognised government of President Abdrabbuh Mansour Hadi and leader of the Ta’izz axis, Khalid Fadhil. In practice, however, the once united front that ousted Houthi and allied forces in 2015 failed the test of time and fragmented as the siege dragged on; a myriad of militias characterised by personalised leadership emerged, creating a complex web of actors and alliances. Figure 10 below shows how armed clashes between the various groups in control of Ta’izz have increased since 2016.

In early August 2018, a series of deadly clashes took place in the central and eastern areas of the city. These pit together fighters led by Adil Abduh Fari Uthman Al-Dhubhani — commonly known as Abu Al-Abbas, who are incorporated into the 35th Armoured Brigade — against Islah-affiliated fighters of the 22nd Armoured Brigade — controlled by both axis leader Khalid Fadhil and Abduh Farhan Ali Salim Al-Mikhlafi, also known as Salim (News Max One, 12 August 2018; Al-Mushahid Net, 12 August 2018). Amid the clashes, Ta’izz governor Amin Mahmoud survived an assassination attempt in the interim southern capital of Aden (Al-Murasil Net, 14 August 2018). Although the attack was never claimed, there is a strong possibility that it was carried out by southern elements of Al-Islah. On 16 September 2018, Islah-affiliated fighters of the 22nd Armoured Brigade openly attacked the governor’s house in Ta’izz (Al-Khabar 21, 17 September 2018).

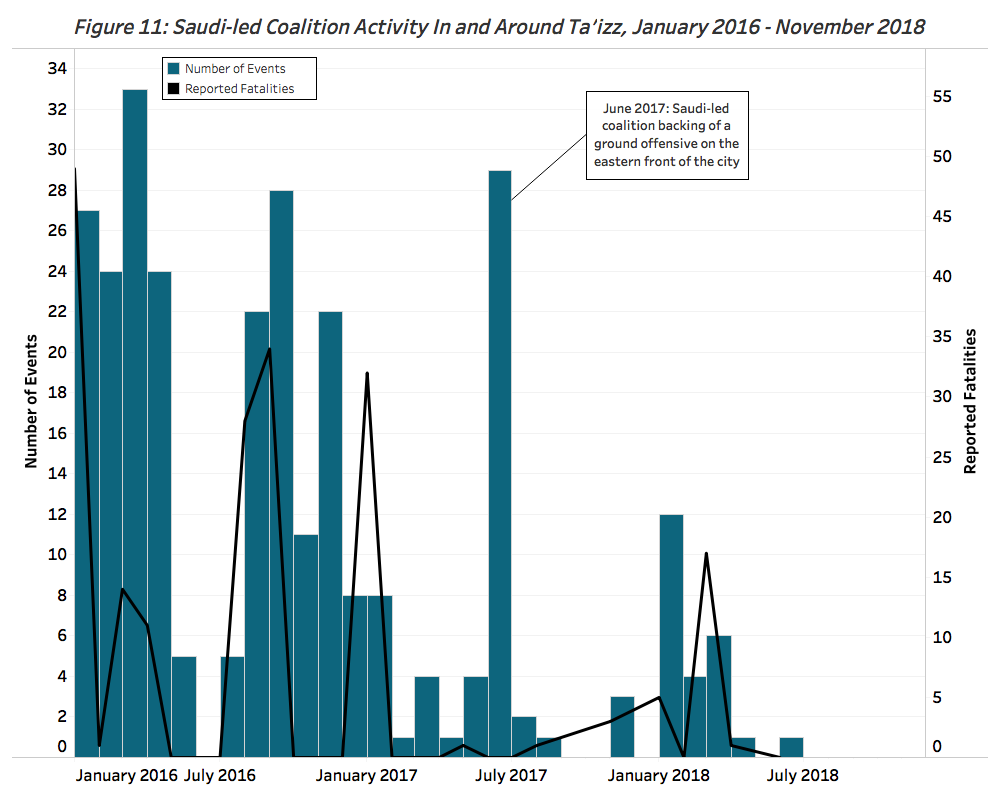

To a certain extent, these local clashes are the direct result of wider regional dynamics. Asserting a more proactive foreign policy in recent years, the UAE has vowed to combat political Islam in all its forms throughout the region and beyond. In Yemen, it is incarnated by the multifaceted Al-Islah party, which Abu Dhabi has come to perceive as a national security threat, and which has traditionally enjoyed strong grassroots support in Ta’izz (Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, 29 September 2017). Breaking the Houthi siege and restoring stability to the city would therefore carry an unthinkable risk for the UAE: the third Yemeni city could fall into the hands of a group that it equates to the Muslim Brotherhood – a transnational organisation listed as a terrorist group by both Riyadh and Abu Dhabi (Reuters, 15 November 2014). The Emirati fear that Al-Islah takes control of Ta’izz if the Houthi siege is lifted largely explains the disengagement of the Saudi-led coalition depicted in Figure 11 below. Since June 2018, ACLED hasn’t recorded any coalition activity in and around the city.

While gradually disengaging itself and the wider coalition from Ta’izz, the UAE upset the local order by fostering the rise of new local revisionist actors to challenge traditional Islah-affiliated figures. In the early stages of the conflict, for instance, the Saudi-led coalition redirected its weapons supply from Hamoud Said Al-Mikhlafi toward Salafi leader Abu Al-Abbas, as it judged Al-Mikhlafi to be too close to Al-Islah, although he was the one who initiated and organised the anti-Houthi fight in the city (Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, 29 September 2017)[13]. By some reports, Abu Dhabi even conditioned the continuation of its support to fighters in Ta’izz on Al-Mikhlafi’s departure from the city, which eventually happened[14], although a number of his fellow tribesmen still maintain important positions (Middle East Eye, 26 November 2018).

It seems, however, that Al-Islah has recently regained prominence, both politically and militarily. This was initiated in early 2018 with the appointment of Salim – the head of Al-Islah in Ta’izz – as advisor to leader of the axis Khalid Fadhil – also an Al-Islah figure – in February (Al-Araby Al-Jadid, 20 February 2018). The party’s ascent ultimately led to the August clashes previously mentioned, and the subsequent withdrawal of Abu Al-Abbas forces from their positions. In a possibly new development, reports allege that Al-Islah is trying to have current Ta’izz governor Amin Mahmoud, considered to be a pro-UAE figure (Al-Arabi, 21 February 2018), replaced by someone more lenient toward the party (Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, 12 November 2018). Looking forward, political and military developments in Ta’izz will likely be determined by the extent to which Abu Dhabi deems the empowerment of Al-Islah acceptable. If recent meetings between the leaderships of both parties are encouraging (Emirates News Agency, 14 November 2018), this will not be the first time such meetings take place, and as previous attempts at detente have failed several times before, the future of Ta’izz and its residents remains highly uncertain.

Hodeidah: Yemen’s lifeline as the turning point of the civil war?

After Houthi and allied forces overtook Sana’a in September 2014, they reached the port city of Hodeidah, located roughly 150 kilometres southwest of the capital, in less than a month. In a matter of days, they secured control over Yemen’s fourth largest city and its second largest port (Reuters, 15 October 2014). Hodeidah has been a strategic location for the Houthis throughout the conflict, providing them with an access to the Red Sea and its maritime traffic. Moreover, as around 75% of all food and humanitarian supplies entering Yemen go through the port of Hodeidah, controlling it has inevitably placed the Houthis as necessary partners of the international community. As such, soon after it helped oust the Houthi-Saleh alliance from Aden in July 2015, the Saudi-led coalition made recapturing Hodeidah from Houthi and allied forces one of its priorities.

Moreover, as the Saudi-led coalition sees Hodeidah as both a financial and weapons Houthi supply line, it has long argued that removing the port from Houthi hands will be a major step toward ending the war. Indeed, customs collection at the Hodeidah port represents a sizable part of Houthi revenues (Chatham House, 20 December 2017). However, some argue that by adding tax collection checkpoints inland, Houthi and allied forces could relatively easily mitigate financial loses that would result from the port’s seizure (International Crisis Group, 21 November 2018). Similarly, while an important rhetoric point of the Saudi-led coalition narrative is that Iranian ballistic missile components enter Yemen through Hodeidah before being assembled in the country and launched onto Saudi territory, the UN, which has come to oversee inspection of ships entering Hodeidah port since May 2016, has found no evidence corroborating these allegations (United Nations Security Council, 26 January 2018).

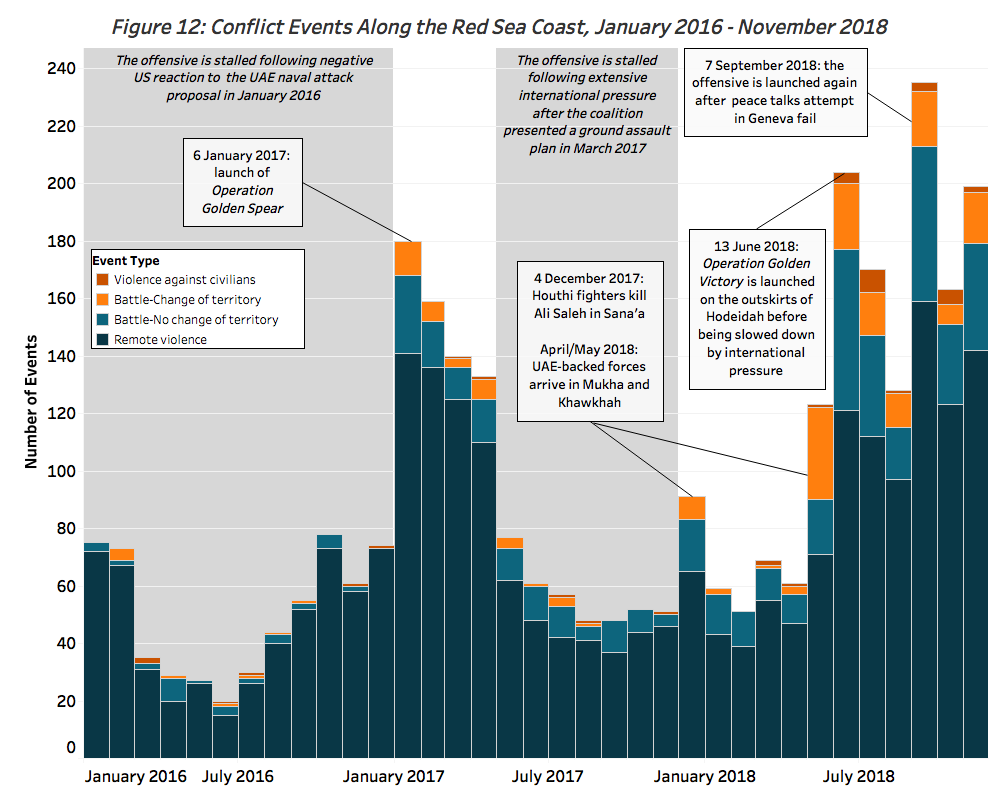

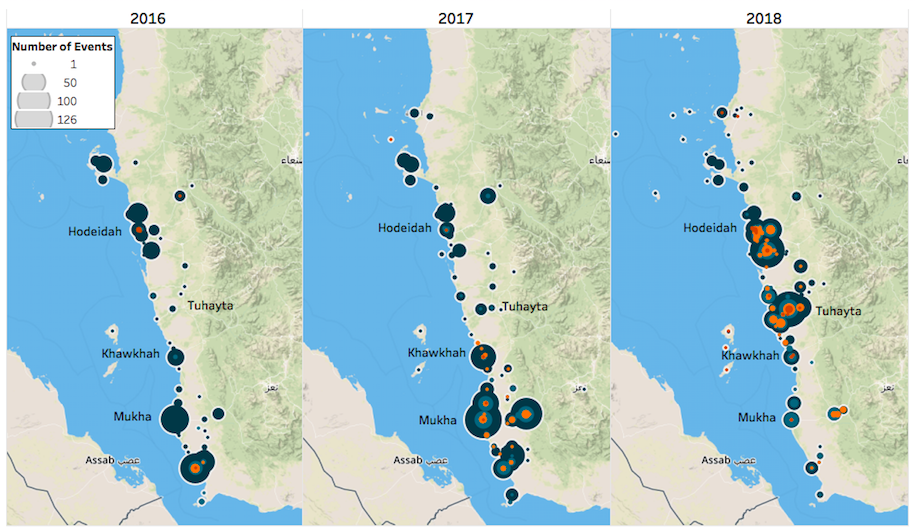

This has not stopped the UAE, which is spearheading the offensive along Yemen’s western coast, to present a naval attack proposal to the US in 2016. The latter was put aside, however, as the Obama administration deemed that it was too risky (Salisbury, 27 June 2018). Instead, the UAE opted for another option, which was initially launched under the name Operation Golden Spear: that of recapturing Hodeidah as part of a wider campaign along the entire Red Sea coast, starting from its southernmost part. Figure 12 below illustrates the various phases of the western coast offensive, which largely stalled until two key events took place within the past year: the collapse of the Houthi-Saleh alliance, which culminated in the killing of former president Saleh by Houthi fighters and revitalised anti-Houthi advances across the country (ACLED, 22 April 2018); and the arrival of UAE-backed forces (for more on UAE-backed forces fighting on the western front see ACLED, 20 July 2018). The on-and-off nature of the campaign can also be explained by international pressure, which has in several occasions brought the potentially disastrous humanitarian consequences of an attack on Hodeidah before the public eye (UN Office of the Humanitarian Coordinator in Yemen, 4 April 2017 and Le Monde, 1 July 2018).

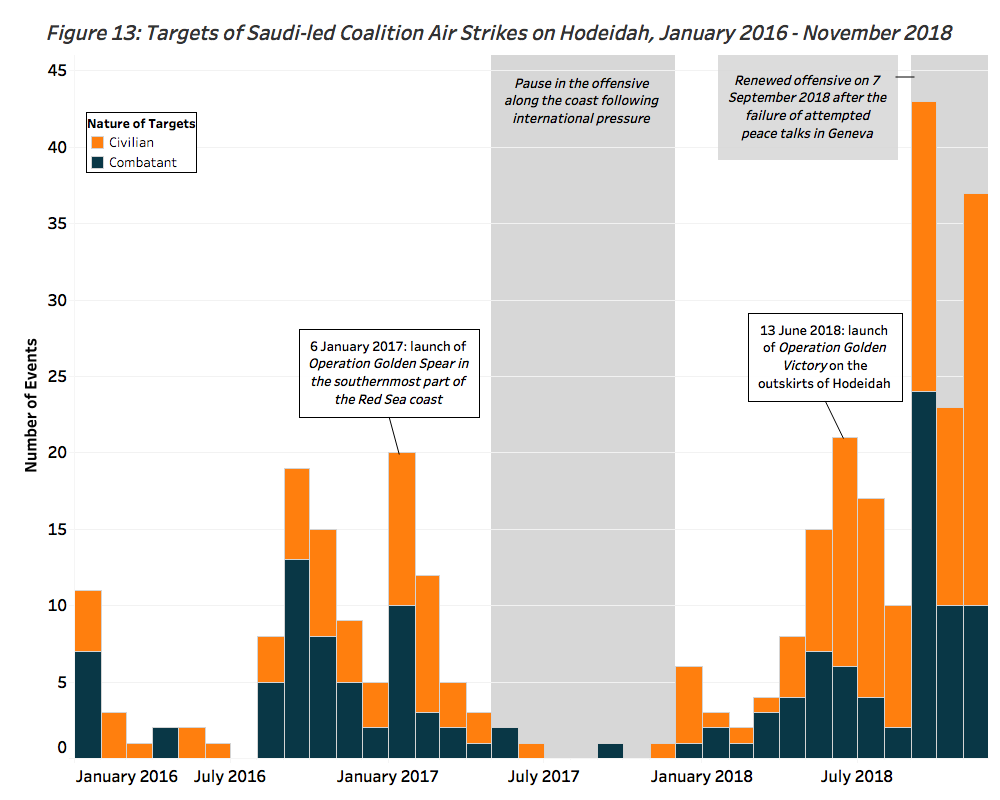

Figure 13 below illustrates that, since 2016, Saudi-led coalition air strikes on the city of Hodeidah have reflected the dynamics of the wider offensive along the Red Sea coast; they in fact seem to have been waged in accordance to the various phases of the campaign. This means that during the last three years, Hodeidah residents have been directly affected by fighting that was taking place some 150 kilometres away from their homes.

According to data collated by ACLED, Saudi-led coalition air strikes have killed the same number of civilians than that of combatants in Hodeidah over the January 2016 – August 2018 period – 99 fatalities in both instances[15]. Since the September 2018 offensive, however, although Figure 13 above shows that air strikes have not necessarily been more precise in targeting military over non-military sites, nearly seven times more combattants have been killed than civilians (200 of the former against 30 of the latter).

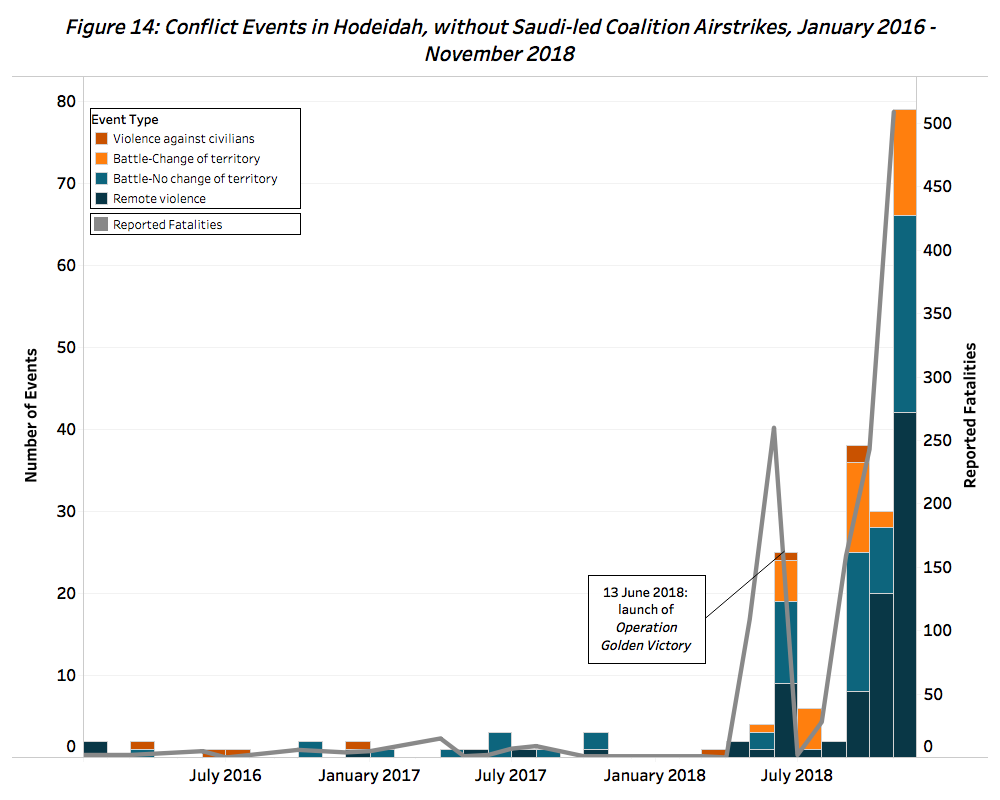

Until the launch of Operation Golden Victory in June 2018, Saudi-led coalition air strikes have represented the large bulk of the violence experienced by the 600,000 residents of the city and its periphery. Figure 14 below, in fact, shows that Saudi-led coalition air strikes aside, Hodeidah has experienced relatively low levels of violence from January 2016 to May 2018. The Figure also shows that fatalities have skyrocketed since the launch of Operation Golden Victory, more than doubling between October and November, from 243 to 509[16].

Before the operation, the battle events in Figure 14 represent sporadic attacks of local Tihami fighters challenging Houthi presence, while the remote violence events represent either the explosion of devices (land and sea mines) or the firing of missiles outside of the city by pro-Houthi forces. From January 2016 to May 2018 – a 29-month period, data collated by ACLED recorded seven civilians killed by Houthi violence; from June 2018 to November 2018 – a six-month period, the data suggest that Houthi violence is responsible for 32 civilian fatalities, including 22 through mortar or artillery shelling. Deliberate or not, this dramatic increase shows that Hodeidah residents have been trapped in the crossfire of the offensive on their city, echoing the words of UN Humanitarian Coordinator in Yemen, Lise Grande, that “the most vulnerable people in the whole country are sitting there in Hodeidah” (The Washington Post, 8 November 2018).

After Houthi and allied forces were caught by surprise by the success of the anti-Houthi offensive south of the city, they turned Hodeidah into a war zone by preparing it for an all-out assault. Trenches were dug across all major roads, thousands of landmines were laid, including in the port and humanitarian facilities (Twitter, 14 November 2018 and Twitter, 19 November 2018), and snipers and gunmen were positioned on rooftops, including on those of medical facilities (Amnesty International, 7 November 2018)[17]. In the meantime, increased violence is threatening to make Hodeidah the epicentre of a new cholera outbreak, which could be more deadly than the one that infected around 1.2 million people across Yemen in 2017 (IRIN, 23 October 2018). Water and sanitation facilities in and around the city have indeed been damaged by Saudi-led coalition air strikes, while Houthi trenches within the city centre have damaged water networks and contaminated the water (OCHA, 2 August 2018).

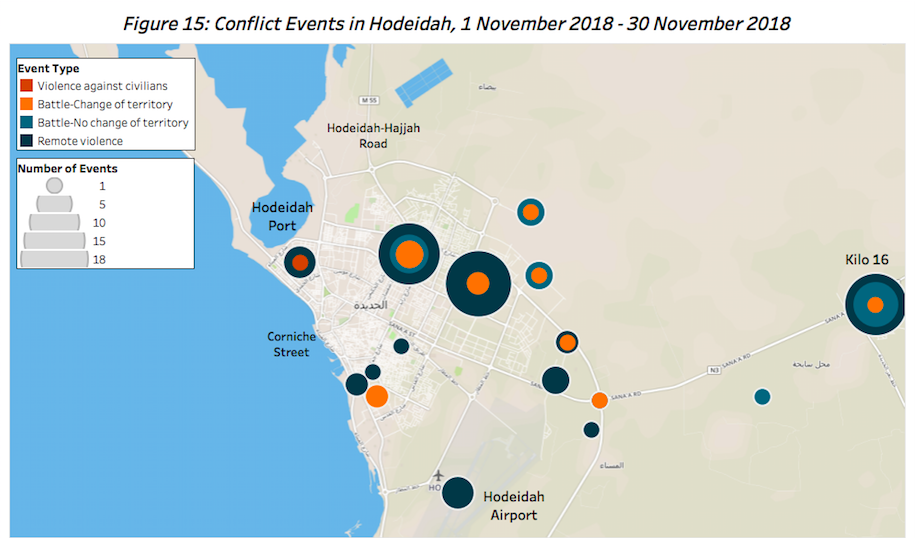

It is in this context that the UAE ultimately launched the November assault on Hodeidah, which is mapped in Figure 15 below, in early November 2018. This relatively unexpected decision seems to have been a reaction to the call for a ceasefire and for peace talks to be held within 30 days, made on 30 October by both US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo and US Secretary of Defense Jim Mattis. If the Saudi-led coalition expressed its willingness to participate in new peace talks, it went forward with the offensive anyway, under the following logic, laid out by Yemen’s Information Minister Moammar al Eryani: “The goal is to take Hodeidah before the 30 days. If Hodeidah is freed, the Houthis will be forced to come and sit with us at the table” (The Washington Post, 8 November 2018). As of early December, beyond the 30-day deadline, Houthi and allied forces remain in control of Hodeidah. The unprecedented pressure exerted on them during the month of November, however, has most likely played in favour of the renewed peace talks that were launched in Sweden on 6 December.

In this latest offensive, UAE-backed forces have managed to engage Houthi and allied forces in Hodeidah city from two fronts: from the southern entrance onto Corniche Street, which passes by the Old City of Hodeidah before leading to the port; and from the eastern entrance to circle around the northern side of the city and cut off the Hodeidah-Hajjah road before reaching the port[18]. On both fronts, the fighting has been waged on-and-off, on a building-by-building basis, with dramatic consequences for the city’s infrastructure and residents (Amnesty International, 12 November 2018). According to data collated by ACLED, more than 600 people, including both combatants and civilians, have been killed in Hodeidah and its outskirts during the month of November, which is more than half of all recorded fatalities in the city over the 34 months of January 2016 – October 2018.

If Emirati officials have signalled, from the early stages of the offensive, that their aim was to adopt a defensive posture ahead of the peace talks (Twitter, 4 November 2018), actions on the ground suggest otherwise. As anti-Houthi forces are making progress around the city, it looks more and more like they are aiming at besieging Houthi and allied forces inside Hodeidah, while taking control of the port. A Yemeni military official has indeed noted that “the battles will not stop, except with the liberation of Hodeidah and the whole west coast” (Middle East Eye, 14 November 2018). While the outcome of the latest UN-led peace talks, on-going at the time of writing, is unclear, questions need to be asked as to what a Houthi-free Hodeidah will look like. Amid the offensive, Executive Director of the World Food Programme David Beasly has indeed asserted that “Houthis are the greatest impediment to delivery of aid on the ground” (Twitter, 19 November 2018). Coalition-backed forces, however, have a poor track record of effectively governing areas under their control.

The best example is perhaps the southern city of Aden, of which this report has already highlighted the pervasive instability although Houthi-Saleh forces were ousted more than three years ago. Compounded by rampant corruption, this has prevented coalition-backed forces from effectively operating the port of Aden to its full capacity, while it is the country’s largest and only deepwater port. If the Houthis are ousted, nothing guarantees that the Saudi-led coalition would operate the port of Hodeidah more effectively than the port of Aden, potentially hindering the delivery of aid to the country in a durable way.

Moreover, as rumours go that the UAE would like to install a GPC fiefdom in Hodeidah led by Tareq Mohammed Saleh, military commander on the Red Sea coast and nephew of former president Ali Abdullah Saleh, to counter Islah-dominated Marib and Ta’izz, increased competition between the armed groups fighting the Houthis is likely. The anti-Houthi front in Hodeidah is indeed all but unified, as it is made up of groups that share little but their desire to defeat the Houthis, and that have clashed on several occasions before (for more on the forces fighting on the western front see ACLED, 20 July 2018). Much like what happened in Aden, infightings are likely to intensify once Houthi and allied forces are ousted from the city, which could result in a post-Houthi Hodeidah characterised by protracted conflict and prolonged instability.

Find an explanation of ACLED’s methodology for monitoring the conflict in Yemen here.

_____________________

[1] ACLED georeferences conflict and protest events to the area within the city where they took place, when reports provide this level of detail. The maps below therefore do not reflect the exact location of the events, but a general approximation of the neighbourhood where they were reported to have occurred.

[2] Senior defections include Information Minister Abdul Salam Ali Jaber and Technical Education Minister Mohsin Ali Al-Naqib. Deputy Education Minister Abdullah Al-Hamadi also fled to Saudi Arabia (Gulf News, 12 November 2018; The National, 14 November 2018).

[3] In November, clashes between the Houthis and tribesmen were reported in Hamdan, northwest of Sana’a, after the Houthis raided a wedding — detaining the groom, his father, and other guests who had fired in the air to celebrate. The groom was killed in unclear circumstances in Darwan police station, sparking clashes that left several people dead. The Houthis had banned celebratory shots being fired at weddings (Asharq Al-Awsat, 13 November 2018).

[4] ACLED researchers are currently working to complete the coding of conflict and protest events for Yemen in 2015. The data release is expected in early 2019, and will provide an estimate of the total fatalities occurring in Aden during the battle.

[5] A map visualising the current distribution of security forces and military checkpoints in Aden is available at: http://sanaacenter.org/publications/yemen-at-the-un/6341#assassinations.

[6] Other notable leaders include former state minister and STC vice president Hani bin Braik, Brig. Gen. Nabil Husayn Ahmad Al-Mashushi – who is currently the commander of the 3rd Brigade of the Giants Brigade in Hodeidah (Volkskrant, 27 July 2018) – and Abdul Nasser Rajeh Al-Bahwa.

[7] On 16 August, two soldiers in the 4th Brigade of the Presidential Protection forces were kidnapped, and their bodies were found three days later in Khormaksar (Aden Al-Ghad, 22 August 2018); a few days later, Presidential Protection and Security Belt forces clashed at a checkpoint manned by the Security Belt (Yemeni Press, 23 August 2018); on 25 August, the commander of the 1st Brigade Sanad Al-Rahwa survived an assassination attempt in Al-Shaab area, near Burayqah (Al-Masirah, 26 August 2018). Mehran Al-Qubati, commander of the 4th Brigade and former Salafist leader of the Al-Mihdhar Brigade, also escaped death on 16 November in Dar Sad, where unidentified gunmen shot at his convoy killing a soldier (Taiz Online, 17 November 2018).

[8] On 1 November, unidentified gunmen opened fire on Naji Al-Yahri, commander of the Security Belt forces in Inma area (Al-Omanaa, 2 November 2018); Abdul Qader Al-Amoudi, the son of a Defence Ministry official, was injured on 14 November when militants riding a motorcycle fired at him in Inma (Sada Aden, 14 November 2018); two days later, the commander of the Presidential Protection forces, Mehran Al-Qubati, survived an assassination attempt in Dar Sad (Taiz Online, 17 November 2018); Brig. Gen. Asaad Gharama, deputy commander of the Abyan Security Belt forces, was shot dead by alleged AQAP militants as he left his house in Inma on 17 November (Anadolu Agency, 18 November 2018); an explosive device planted under the car of the director of airport security was defused in the Umar Al-Mukhtar area on 19 November (Aden Al-Ghad, 19 November 2018); a Subaihi tribesman was killed in Dar Sad on 21 November by men wearing military uniforms, sparking protests outside a military compound housing pro-Hadi forces (Al-Sahwa, 21 November 2018).

[9] On 15 October, Hadi sacked his Prime Minister, Ahmed bin Daghr, citing negligence in dealing with the economic crisis and announcing an investigation over his government’s inefficiency. Bin Daghr was replaced with the former Minister for Public Works and Roads, Maeen Abdulmalik Saeed (Al-Jazeera, 16 October 2018).

[10] Hadi appointed former deputy governor Ahmed Salim Rubea as new governor of Aden on 8 November (Asharq Al-Awsat, 9 November 2018). He replaced Abdulaziz Al-Muflehi, who resigned in November 2017 accusing the Yemeni government of corruption (Reuters, 17 November 2017).

[11] Between January 2016 and November 2018, 392 civilians were reportedly killed as a result of directly targeted violence (this excludes collateral civilian fatalities that are the result of clashes between armed groups). Over the same period, ACLED recorded 339 civilian fatalities in Sana’a, 260 in Hodeidah, and 147 in Aden.

[12] Note that the map excludes 63 events where ACLED researchers were unable to confirm the exact location within Ta’izz. These events were georeferenced at a general city location in the centre of Ta’izz, despite taking place elsewhere.

[13] Note that Abu Al-Abbas was put on the US and Saudi lists of designated terrorists because of his ties to Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) and the Islamic State in October 2017 (Al-Omanaa, 25 October 2017).

[14] Al-Mikhlafi left Ta’izz for Riyadh in March 2016, where he is now supposedly based.

[15] Note that these figures do not include (1) air strikes and associated fatalities that take place as part of ground combat, and (2) civilian fatalities that can be the result of air strikes on military targets that are effectively struck (i.e. collateral damage).

[16] Note that these numbers do not account for fatalities caused by air strikes that are not supporting ground clashes. These figures, however, are addressed later in the report.

[17] The New York Times reports that the UN had to intervene to prevent coalition forces from bombing a hospital on which Houthi forces were stationed (The New York Times, 6 November 2018).

[18] Note that the Hodeidah-Hajjah road is the last remaining road leading out of the city of Hodeidah that is still open.